Where is the Ark of the Covenant?

Speculating on the whereabouts of the lost Ark of the Covenant has been a time-honored parlor game for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. It is easy to trace the Ark of the Covenant through the Bible, from the time of its creation during the days of Moses until the time it was placed within the Holy of Holies in the Temple during the days of David and Solomon. But sometime between 970 B.C. and 586 B.C. the ark disappeared. What happened to it? Where did it go?

Suggestions for the present location of the ark have ranged from a hidden chamber deep within the Temple Mount in Jerusalem or a cave on Mount Nebo in modern Jordan to a church treasury in Ethiopia or a government warehouse in Washington, D.C. But does it even still exist? Might it have been melted down or otherwise destroyed thousands of years ago? Surely such a fearsome weapon—for that is how it is described in the Hebrew Bible—would have been put to use after it left Judean hands, so why does it disappear from history? Such questions have never been satisfactorily answered, despite numerous attempts to solve the riddles and to locate the missing ark.

The ark is mentioned numerous times in the Hebrew Bible. We first meet it at Mount Sinai. The story of how it is made is told to us several times, initially in a more extensive set of instructions in Exodus 25:10-22, and then in an abbreviated description as it is actually being made by the craftsmen Bezalel and Oholiab in Exodus 37:1-9. For the sake of brevity, let us look at the latter version:

The Ark of the Covenant, depicted here in an 18th-century fresco by Luigi Ademollo, was extremely well-traveled before it was finally brought to Jerusalem by King David. (Illustration Credits 6.1)

Bezalel made the ark of acacia wood; it was two and a half cubits long, a cubit and a half wide, and a cubit and a half high [about 4 feet 2 inches long by 2.5 feet wide by 2.5 feet high]. He overlaid it with pure gold inside and outside, and made a moulding of gold round it. He cast for it four rings of gold for its four feet, two rings on one side of it and two rings on its other side. He made poles of acacia wood, and overlaid them with gold, and put the poles into the rings on the sides of the ark, to carry the ark. He made a mercy-seat of pure gold; two cubits and a half was its length, and a cubit and a half its width. He made two cherubim of hammered gold; at the two ends of the mercy-seat he made them, one cherub at one end, and one cherub at the other end; of one piece with the mercy-seat he made the cherubim at its two ends. The cherubim spread out their wings above, overshadowing the mercy-seat with their wings. They faced one another; the faces of the cherubim were turned towards the mercy-seat. (Exodus 37:1-9)

In his final speech to the Israelites, Moses says that he had only placed in the ark the two tablets of stone containing the Ten Commandments (Deuteronomy 10:1-5). This is reiterated in II Chronicles 5:10 as well as I Kings 8:9: “There was nothing in the ark except the two tablets of stone that Moses had placed there at Horeb, where the Lord made a covenant with the Israelites, when they came out of the land of Egypt.”

Of course, we know from the Bible that the tablets Moses placed in the ark were the second set he had been given, since he had smashed the original pair when he first came down the mountain and found the people worshipping a golden calf (Deuteronomy 9:10-17). Some later religious authorities believe that the smashed first set of tablets was placed in the ark along with the intact second set of tablets. Other later authorities suggest that additional items were placed in the ark, such as the staff of Aaron and a vessel containing manna, but these are all disputed.

The subsequent history of the ark can be easily traced throughout the books of the Hebrew Bible, although there are some scholarly disputes about the details. At first, the ark was based in Gilgal. From there, it was taken out as needed and carried in front of the Israelite army during Joshua’s campaigns against Jericho (Joshua 4:19–6:27) and the other cities of the land, including Ai, Gibeon, Makkedah, Libnah, Lachish, Eglon, Hebron, Debir, and Hazor (7:1-14:6). Following these conquests, Joshua then moved the ark to Shiloh, when the “whole congregation of the Israelites assembled … and set up the tent of meeting [the Tabernacle] there” (18:1).

The ark remained at Shiloh for an unspecified period, from the time of Joshua’s death until the Old Testament prophet Samuel was a child. At one point during this period, the ark is said to have been in the city of Bethel, where “Phinehas son of Eleazar, son of Aaron, ministered before it in those days” (Judges 20:26-28), but this was either temporary or, more likely, reflects an alternate tradition woven into the otherwise seamless biblical account. When we meet the ark again, it is resting comfortably within the “tent of meeting” or the “temple of the Lord” at Shiloh, where it is tended by Eli and his two sons (I Samuel 1:3–3:3).

The Israelites’ habit of taking the ark to war with them eventually turned out to be not such a good idea. Sometime during the 11th century B.C., in a battle against the Philistines in the region of Ebenezer and Aphek during the time of Samuel, the Israelites were defeated. The two sons of Eli, who had brought the ark to the battlefield, were killed, and the ark itself was captured by the Philistines (I Samuel 4:1-11).

The Philistines only kept the ark for seven months, moving it from Ashdod to Gath to Ekron, three of their five major cities, as the inhabitants of those cities were in turn afflicted by tumors (I Samuel 5:5–6:1). Eventually they had enough and sent the ark back to the Israelites in the city of Beth-shemesh (I Samuel 6:1-18), since Shiloh had apparently been destroyed in the interim (Psalms 78:59-67; Jeremiah 26:6-9). It was soon moved to the city of Kiriath-jearim, where it remained at the house of Abinadab for the next 20 years (I Samuel 7:1-2).

Then when Saul came to the throne as the first king of Israel, toward the end of the 11th century B.C., the ark apparently began to travel with the army again, because we are told, “At that time the ark of God went with the Israelites” (14:18). Eventually, it came back to rest in Kiriath-jearim; when David decided to make Jerusalem his capital city and to move the ark there, his men went to the house of Abinadab in Kiriath-jearim in order to fetch it (II Samuel 6:1-3; I Chronicles 13:1-8).

The Bible reports, however, that while the ark was being transported to Jerusalem, God struck Uzzah, a son of Abinadab, dead on the spot “because he reached out his hand to the ark” (II Samuel 6:6-7; I Chronicles 13:9-10). Much has been made of this incident by modern enthusiasts, who have sought to provide a scientific explanation for what transpired; some have gone so far as to suggest that the ark was some sort of electric generator and that Uzzah was electrocuted. This suggestion is completely without merit or support, but it remains a favorite topic, as we shall see later.

David was disheartened by this incident and instead of bringing it immediately to the city of Jerusalem, he left the ark at the house of Obed-edom the Gittite. It remained at Obed-edom’s house for three months (II Samuel 6:10-11; I Chronicles 13:13-14) until David finally brought it to the city amid much rejoicing, leaping, dancing, shouting, and blowing of trumpets (II Samuel 6:12-15; I Chronicles 15:1-28; II Chronicles 1:4). Once within the city limits, the ark was placed inside the tent that David had pitched for it (the Tabernacle; see II Samuel 6:17 and I Chronicles 16:1). Here it stayed until Solomon built his famous Temple and moved the ark to its final resting place in the Temple’s Holy of Holies in about 970 B.C. (I Kings 6:19, 8:1-13; II Chronicles 5:2-10).

The ark is not mentioned again in the Hebrew Bible until it surfaces during the time of King Josiah in the seventh century B.C. It is therefore possible that the ark simply remained in Solomon’s Temple for some 360 years, although this is a matter of some debate. In any event, we are told in II Chronicles 35:1-3: “Josiah … said to the Levites who taught all Israel and who were holy to the Lord, ‘Put the holy ark in the house that Solomon son of David, king of Israel, built; you need no longer carry it on your shoulders. Now serve the Lord your God and his people Israel.’ ”

It is not completely clear why the ark had to be put back into Solomon’s Temple during Josiah’s time, or where it had been, if indeed it had been removed from the Temple even temporarily. One scholar has suggested that the Ark of the Covenant had possibly been removed during the rule of King Manasseh (698 to 644 B.C.), when he set up an Asherah image in the Temple, but this may not have anything to do with Josiah’s statement.

In any event, it seems that the last time the ark was seen by anyone was during the reign of King Josiah, who ruled from 639 to 609 B.C. In addition to the Book of II Chronicles, the Book of Jeremiah also mentions the ark during Josiah’s time:

The Lord said to me in the days of King Josiah.… And when you have multiplied and increased in the land, in those days, says the Lord, they shall no longer say, “The ark of the covenant of the Lord.” It shall not come to mind, or be remembered, or missed; nor shall another one be made. At that time Jerusalem shall be called the throne of the Lord, and all nations shall gather to it, to the presence of the Lord in Jerusalem, and they shall no longer stubbornly follow their own evil will. In those days the house of Judah shall join the house of Israel, and together they shall come from the land of the north to the land that I gave your ancestors for a heritage. (Jeremiah 3:6, 16-18)

Unfortunately, the context and meaning of this passage are unclear. Many scholars interpret the passage as a prophecy of a time the ark will no longer be needed; others view it as a statement about the ark having been seen in Josiah’s or Jeremiah’s time.

The ark is not mentioned again in the Hebrew Bible, except in the Psalms. In Psalm 132:8, the reference simply says, “Rise up, O Lord, and go to your resting-place, you and the ark of your might.” However, Psalm 78:60-61 may contain an allusion to the capture of the ark by the Philistines: “He abandoned his dwelling at Shiloh, the tent where he dwelt among mortals, and delivered his power to captivity, his glory to the hand of the foe.”

Most important, the Bible does not list the ark among the treasures and other items that Nebuchadnezzar and the Neo-Babylonians took from Jerusalem during their attacks on the city in 598, 597, and 587-586 B.C. The only items the Hebrew Bible mentions that Nebuchadnezzar carried away are unspecified “vessels.” For instance, we are told that in 598 B.C., “Nebuchadnezzar … carried some of the vessels of the house of the Lord to Babylon and put them in his palace in Babylon” (II Chronicles 36:7). In 597 B.C., “King Nebuchadnezzar sent … to Babylon … precious vessels of the house of the Lord …” (36:10). Finally, in 586 B.C., “All the vessels of the house of God, large and small, and the treasures of the house of the Lord, and the treasures of the king and of his officials, all these he brought to Babylon. They burned the house of God, broke down the wall of Jerusalem, burned all its palaces with fire, and destroyed all its precious vessels” (36:18-19). Here we must note again that neither the ark nor any of the objects usually associated with it is mentioned.

Additionally, the ark is not referenced among the objects that the Jewish exiles brought back to Jerusalem upon their return from Babylon in 538 B.C., either in the biblical account or in any of the extant inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar or Cyrus the Great. For example, we are told in the Book of Ezra that:

King Cyrus himself brought out the vessels of the house of the Lord that Nebuchadnezzar had carried away from Jerusalem and placed in the house of his gods. King Cyrus of Persia had them released into the charge of Mithredath the treasurer, who counted them out to Sheshbazzar the prince of Judah. And this was the inventory: gold basins, thirty; silver basins, one thousand; knives, twenty-nine; gold bowls, thirty; other silver bowls, four hundred and ten; other vessels, one thousand; the total of the gold and silver vessels was five thousand four hundred. All these Sheshbazzar brought up, when the exiles were brought up from Babylonia to Jerusalem. (Ezra 1:7-11)

Again, we must note that despite the list’s minute detailing of the treasures, neither the ark nor any of its associated items is mentioned.

Thus, the last time the ark was definitely seen by anyone was when Solomon placed it within the Holy of Holies inside the Temple in Jerusalem during the tenth century B.C. If the mentions of the ark in II Chronicles and Jeremiah are considered to be true contemporary references to the ark during the time of Josiah, then we can say that it apparently sat in the Temple for some 360 years and was still there during the time of Josiah at the end of the seventh century B.C. However, if the mentions of the ark in II Chronicles and Jeremiah are discounted, as many scholars suggest, then the ark simply disappeared some time after the reign of Solomon. As Bezalel Porten, professor of Jewish history at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem says, “The mystery of the Ark stems from the silence of the Bible after we are told that it was placed in the Holy of Holies of Solomon’s Temple (I Kings 8:6). Nowhere in the Bible, neither in the account of the Babylonian destruction of the Temple in 587/6 B.C.E. (II Kings 2:5), nor anywhere else, is there an indication of the fate of the ark. Over the years, its curious disappearance has given rise to a great deal of speculation.”

There are, however, two additional mentions of the ark that are of great interest, if we can trust them. These are found in the Apocrypha—books that are not always included in our modern version of the Bible. In the Book of II Esdras, we are told that the Ark of the Covenant was “plundered” when Jerusalem was destroyed by the Neo-Babylonians in 586 B.C.:

… the sorrow of Jerusalem. For you see how our sanctuary has been laid waste, our altar thrown down, our temple destroyed; our harp has been laid low, our song has been silenced, and our rejoicing has been ended; the light of our lampstand has been put out, the ark of our covenant has been plundered, our holy things have been polluted, and the name by which we are called has been almost profaned; our children have suffered abuse, our priests have been burned to death, our Levites have gone into captivity, our virgins have been defiled, and our wives have been ravished; our righteous men have been carried off, our little ones have been cast out, our young men have been enslaved and our strong men made powerless. (II Esdras 10:20-22)

The Neo-Babylonian attacks on Jerusalem eventually left the city in ruins and the Temple of Solomon completely destroyed, as depicted in this 19th-century painting by Eduard Bandemann. (Illustration Credits 6.2)

In the Book of II Maccabees, however, we are told that the prophet Jeremiah secretly hid the Ark of the Covenant, along with other objects: “The prophet, having received an oracle, ordered that the tent and the ark should follow with him, and … he went out to the mountain where Moses had gone up and had seen the inheritance of God. Jeremiah came and found a cave-dwelling, and he brought there the tent and the ark and the altar of incense; then he sealed up the entrance” (II Maccabees 2:4-5). This would have occurred sometime after Josiah’s death in 609 B.C. but before Jeremiah was taken off to Egypt following the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in 586 B.C.

This brief mention in II Maccabees has given rise to all sorts of speculation as to which mountain this was. This is probably a moot point, however, since most scholars interpret it as Mount Nebo, based on the description in Deuteronomy 34:1-4: “Then Moses went up from the plains of Moab to Mount Nebo, to the top of Pisgah, which is opposite Jericho, and the Lord showed him the whole land: Gilead as far as Dan, all Naphtali, the land of Ephraim and Manasseh, all the land of Judah as far as the Western Sea, the Negeb, and the Plain—that is, the valley of Jericho, the city of palm trees—as far as Zoar. The Lord said to him, ‘This is the land of which I swore to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, saying, “I will give it to your descendants”; I have let you see it with your eyes, but you shall not cross over there.’ ” This, too, we shall soon discuss at greater length.

IN OUR REVIEW of the textual evidence, we may first note that the Ark of the Covenant is not mentioned in any contemporary extra-biblical references. Not one of the many enemies (or friends) of ancient Israel from the time of Moses through Solomon, or of ancient Judah from the time of Rehoboam through Josiah, ever mentions the ark, even in passing. Nor is it mentioned in the Hebrew Bible during the four centuries between Solomon and Nebuchadnezzar in connection with the many kings of Judah who were either threatened by enemies or had to dip into the Temple’s coffers to pay off an enemy.

This is extremely surprising, because the biblical account tells us that the treasures kept in Solomon’s Temple were plundered at least eight times between 970 and 586 B.C. According to the Bible, the Temple was (1) either looted by Shishak or used by Rehoboam to bribe Shishak in 925 B.C.; (2) used by Asa of Judah to bribe Ben-Hadad of Aram-Damascus in 875 B.C.; (3) either looted by Hazael of Aram-Damascus or used by Jehoash of Judah to bribe Hazael in 800 B.C.; (4) looted by Jehoash of Israel in 785 B.C.; (5) used by Ahaz of Judah to bribe Tiglath-pileser III of Assyria in 734 B.C.; (6) either looted by Sennacherib of Assyria or used by Hezekiah of Judah to bribe Sennacherib in 701 B.C.; (7) looted by Nebuchadnezzar of Babylonia in 598/597 B.C.; and (8) looted again by Nebuchadnezzar in 587/586 B.C.

If either Shishak, Hazael, Jehoash, or Sennacherib succeeded in looting the Temple, rather than agreeing to be paid off via a bribe, then the ark could have disappeared in either 925, 800, 785, or 701 B.C., rather than in the more commonly suggested years of 597 or 586 B.C. at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar. In fact, several of these possibilities have been investigated, or at least suggested by enthusiasts—with Shishak being a particular favorite. But if Shishak had taken the ark, we would expect to find a mention of it in Egyptian inscriptions, which we have not.

In fact, the ark is only mentioned in a few extra-biblical sources, the most important of which are an Ethiopian legend and three rabbinical accounts, all written centuries after its disappearance. Two of these rabbinical accounts are in the Talmud—the rabbinic discussions pertaining to Jewish law, ethics, customs, and history, compiled between the first and fifth centuries A.D.—when the rabbinical authorities were musing over its disappearance. The third is found in the Mishneh Torah, the code of Jewish law written by the famous Rabbi Maimonides about 800 years ago (during the late 12th century A.D.), which is followed by many Orthodox Jews today, particularly the Chabad Hasim.

The first reference in the Talmud is essentially a footnote to a statement made about a priest who was in the Temple’s Sanctuary and “noticed that one of the paving-stones on one place appeared different from the others. He went out to tell others of it; but he had not yet finished speaking, when he gave up the ghost; thereby it was known to a certainty that the ark of the covenant was hidden there.” A note after the words “ark of the covenant” explains:

The ark was hidden during the existence of the first Temple in order to save it from the Babylonians, after all hope had been abandoned, and its hiding-place was underground. The priests who subsequently took charge probably noticed some sign made by the former generation when the ark was hidden, and this particular priest died as a consequence of his attempt to reveal the secret. (Shekalim 6:1-2)

The whereabouts of the Ark of the Covenant have been a source of discussion for more than 2,000 years, including by Maimonides, whose Mishnah Torah manuscript is pictured here. (Illustration Credits 6.3)

The second reference in the Talmud is found in a lengthy discussion concerning the location of the ark (Yoma 53b–54a). Here, the rabbis note that several different opinions had been expressed as to its location: Some argued that it had been carried off to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar; others argued that it had been hidden by Josiah; still others argued that it was concealed within or underneath the Temple itself. In the end, despite the lengthy discussion, the rabbis were unable to reach a consensus or conclusion.

As for the reference found in Maimonides’s Mishneh Torah, we are told: “When King Solomon built the Holy Temple, knowing that it was destined to be destroyed, he built a place in which to hide the Ark, [at the end of] hidden, deep, winding passageways. It was there that King Josiah placed the Ark twenty-two years before the Temple’s destruction, as related in the Book of Chronicles” (Mishneh Torah, Laws of the Holy Temple 4:1). We do not know where Maimonides got his information, particularly the idea that Josiah placed the ark in a hidden location within the Temple or Temple Mount “twenty-two years before the Temple’s destruction.”

We must be careful when evaluating such declarations, particularly because counting back 22 years before the Temple’s destruction in 586 B.C. brings us to 608 B.C. And Josiah could not have hidden the ark in 608 B.C., because he was killed in a battle at Megiddo one year earlier, in 609 B.C. So at the very least we must correct Maimonides’s chronology—unless we suggest that Maimonides was counting backward from the beginning of the siege of Jerusalem in 587 B.C., rather than the end in 586 B.C. If so, then 22 years earlier would have been precisely 609 B.C., and we could argue that Josiah hid the ark before he met the Egyptians at Megiddo and was killed in battle.

It is precisely because of these late declarations in the Talmud and the Mishneh Torah—especially one reference during the discussion in the Talmud to I Kings 8:8 where it says, “The poles were so long that the ends of the poles were seen from the holy place in front of the inner sanctuary; but they could not be seen from outside; they are there to this day” (emphasis added)—that many Orthodox Jews and others believe that the ark is hidden in a subterranean chamber or vault under the Temple Mount. On the other hand, as we shall see, a minority of people believe it was carried off to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar.

In addition, there is a discussion concerning the whereabouts of the ark in the Ethiopian Kebra Nagast (Book of the Glory of Kings), now well known to all ark seekers because of Graham Hancock’s best-selling book, The Sign and the Seal. The Kebra Nagast has given rise to the belief that the ark is in Aksum, Ethiopia. It contains a description of how Solomon and the Queen of Sheba met; it also claims that the ark was brought back to Ethiopia by Prince Menelik I (a son born of the amorous union between King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba) after his journey to visit Solomon. We will discuss this possibility further as well.

SO FAR WE HAVE looked extensively at the biblical account of the ark’s history, from its creation to its ultimate disappearance sometime between the time of Solomon in 970 B.C. and Nebuchadnezzar in 586 B.C. We have also briefly discussed the available extra-biblical literary data. But is there any archaeological evidence to help trace the journey of the Ark of the Covenant, to confirm its time in Solomon’s Temple, or to help determine where it is now?

We will discuss the various suggestions made by enthusiasts searching for the ark, as well as the claims of those who believe they have already found it, some of which involve archaeology. But in terms of tracing the path of the ark before it came to rest in Jerusalem, the short answer is that we have no real archaeological evidence. This is not surprising, for we are almost never told where in the various cities the ark was kept. Even in those few instances when we are given a specific location, such as the house of Abinadab in the city of Kiriath-jearim, where the ark remained for 20 years, we have not been able to find and excavate the specific location, despite occasional claims to the contrary.

In terms of confirming the length of its stay in Solomon’s Temple, however, we may be able to use some archaeology. Even here, though, we are at a tremendous disadvantage, since no authorized excavations have been conducted on the Temple Mount by professional archaeologists in recent decades. The closest that we get to such excavations are the amateur explorations by British, French, and American explorers during the 1800s, the Israeli excavations around and nearby the Temple Mount during the past 50 years (including the excavations by Benjamin Mazar and now Eilat Mazar, as well as the tourist tunnel running along the Western Wall), and the illegal digging conducted by the Islamic Waqf in the late 20th century, during the construction of the new Marwani mosque.

From the early amateur explorations by people such as Frederick Catherwood, James Barclay, Charles Wilson, and Charles Warren, we have records of the “vast network of reservoirs” that lie beneath the Temple Mount, including the spot below where the First and Second Temples once stood and where the modern Dome of the Rock now stands. These have not been entered, at least officially, for decades, but they do lend support to the possibility that the ark could have been hidden below the Temple in antiquity.

Neither the excavations nor the illegal digging have helped us ascertain whether the ark was on the Temple Mount, but they do provide circumstantial evidence that Solomon’s Temple was located there. For example, during the sifting of the dumped debris from the Temple Mount, the team led by Israeli archaeologists Gabriel Barkai and Tzachi Zweig found “a First Temple period bulla, or seal impression, containing ancient Hebrew writing, which may have belonged to a well-known family of priests mentioned in the Book of Jeremiah.” Such findings also help discount the political statements by Yasser Arafat and other Islamic leaders that Solomon’s Temple was not located in Jerusalem—claims that can be dismissed outright, as several scholars (including myself) have shown.

Moreover, in his recent book, The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, Leen Ritmeyer, an architect who has participated in excavations in Jerusalem for more than 30 years (and who wrote his Ph.D. thesis on “The Architectural Development of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem” at the University of Manchester), speculates on the Ark of the Covenant’s original location on the Temple Mount. He identifies a rectangular depression cut into the actual rock (inside the Dome of the Rock) as the place the ark could have stood within the Holy of Holies in Solomon’s Temple, and suggests that the flat area would have stopped the ark from wobbling “in an undignified manner.” Of course, there is no way to know whether Ritmeyer is correct, but it is an interesting speculation nevertheless.

Finally, in reviewing the archaeological evidence, we should discuss the ark’s very nature. The ark was specifically built as a container to hold the tablets that Moses brought down from Mount Sinai. In this regard, it closely resembles other such containers found in the ancient Near East. Some of these, such as one well-known wooden chest found in the tomb of Tutankhamun in Egypt, were even equipped with long poles to carry them, just as the ark was.

In short, the ark, and its use as a container, is certainly not out of place in the ancient Near East, especially in a culture like the Israelites’, who had supposedly just emigrated from Egypt. Outlandish suggestions—such as the claim that the ark was a transmitter Moses used to talk to God (which comes to us courtesy of Erich von Däniken and his book Chariots of the Gods), or that it was a fearsome weapon that could be used to kill enemies on a battlefield (as seen in Raiders of the Lost Ark), or that it was an electric generator or transformer of some kind (which would provide a scientific explanation for why Uzzah, son of Abinadab, was killed instantly when he reached out to steady the ark)—all must be dismissed outright, because there is no evidence whatsoever for such claims.

WHILE THERE ISN’T any direct archaeological evidence that can help us answer where the Ark of the Covenant is today or what happened to it, there is no shortage of suggestions made by enthusiasts. In fact, even though there is absolutely no solid evidence that the Ark of the Covenant still exists today, more theories have been suggested concerning the ark than for any of the other mysteries we have discussed.

So far, it has been claimed that the ark was hidden under the Temple Mount by either Solomon or Josiah; hidden on Mount Nebo or elsewhere in Jerusalem by Jeremiah; hidden in a Dead Sea cave at Qumran; carried off to Egypt by Shishak; carried off to Ethiopia by Menelik; carried off to Babylon or destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar; removed by Manasseh; buried underneath a Hamas training camp in the West Bank; or crated in a government warehouse in Washington, D.C. Are any of these based on fact or are they sheer speculation? Let us briefly go through each of these suggestions and see if any of them stand up to scrutiny.

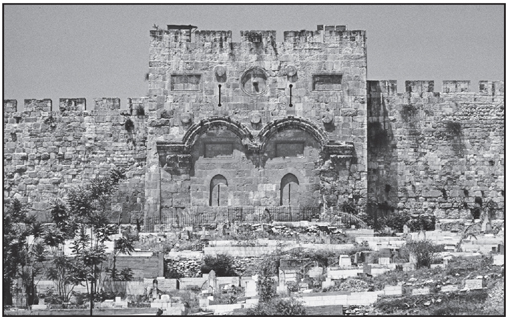

The Temple Mount in Jerusalem has a large number of reservoirs and chambers underneath where the Temple of Solomon stood. Could the ark be buried here? (Illustration Credits 6.4)

Under the Temple Mount—One of the most popular hypotheses today is the one stating that the ark is presently in a secret chamber deep within the Temple Mount, underneath the present-day Dome of the Rock. Basing this claim on the references in II Chronicles, Jeremiah, II Maccabees, the Talmud, and the Mishneh Torah, devotees of the various versions of this theory believe that the ark was hidden either by Solomon immediately after moving it into the Temple in the tenth century B.C., by Josiah sometime during his reign toward the end of the seventh century B.C., or by Jeremiah immediately before the Neo-Babylonian destruction of the Temple in 586 B.C.

For example, the Temple Institute, an ultra-Orthodox Jewish group based in Jerusalem that is dedicated to rebuilding the Temple, says Josiah hid the ark in a special place prepared by Solomon within the bowels of the Temple Mount. They say further, “This location is recorded in our sources, and today, there are those who know exactly where this chamber is. And we know that the ark is still there, undisturbed, and waiting for the day when it will be revealed.”

There are several stories circulating that claim digs have been conducted under the Temple Mount in search of the ark, and that the ark has been found there. The most famous story claims that during the excavations of the present Western Wall tunnel in the early 1980s, two rabbis noticed water seeping from a wall. Moving a stone, they found a vaulted chamber, and then a second, lower, chamber in which they either saw or expected to see the Ark of the Covenant, along with the Table of Shewbread and the seven-branched candelabra. Before they could remove the objects or even record their existence, however, the Islamic authorities sealed up the entrance to the chambers.

Of course, the story has never been fully documented or confirmed by official authorities. The closest that we can get to a semiofficial statement is along the lines of a mention that Leen Ritmeyer made in his book The Quest. Ritmeyer says, “In 1981 workers of the Religious Affairs Ministry carried out a dig under the Temple Mount in search of the Ark. However, when this caused disturbances among the Arab population, the project was aborted.” In his book Searching for the Ark of the Covenant, however, Randall Price provides details of an unofficial investigation that he conducted in the early 1990s, including interviews with several of the rabbis who were reportedly involved. Price’s interviews document that the rabbis differ in the details of their stories and also diverge on whether they did or did not actually see the ark during their excavations.

There is no problem with this theory in and of itself, as it is based on an interpretation of the textual sources. The problem lies with the fact that nobody has been able to verify the claims that have been made about the existence of the objects in a chamber deep below the Temple Mount. We shall have to wait until permission is granted for archaeologists to investigate further, and that permission is unlikely to come anytime soon.

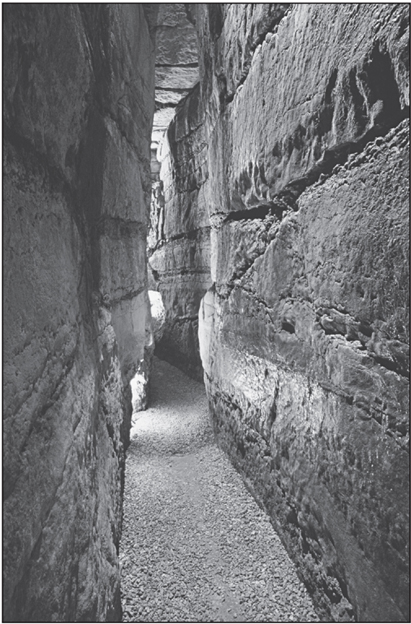

Within the Western Wall tunnel, visitors can walk alongside masonry dating to the time of Herod the Great. (Illustration Credits 6.5)

Elsewhere in Jerusalem—Another theory is that the ark was hidden in Jerusalem by Josiah, Jeremiah, or someone else, but not underneath the Temple Mount. Ron Wyatt, whom we have met in previous chapters, used the references in II Maccabees and other more dubious literary sources, including a late source called The Paralipomena of Jeremiah, to suggest that the Ark of the Covenant was hidden just before the destruction of the Temple in 586 B.C.

According to Wyatt’s wife, he had never intended to search for the ark. As she writes on the Wyatt Archaeological Research Web site, “While waiting for his return flight to the United States [in 1978], Ron was walking along an ancient stone quarry, known to some as ‘the Calvary Escarpment.’ As he was walking, he began conversing with a local authority about Roman antiquities. At one point, they stopped walking, and Ron’s left hand pointed to a site being used as a trash dump and he stated, ‘That’s Jeremiah’s Grotto and the Ark of the Covenant is in there.’ Even though these words had come from his own mouth and his own hand had pointed, he had not consciously done or said these things. In fact, it was the first time he had ever thought about excavating for the Ark.”

According to the Wyatt Archaeological Research Web site, after researching the biblical accounts, Ron Wyatt began excavating for the Ark of the Covenant the very next year, in January 1979, within a cave system located north of the Damascus Gate in Jerusalem. After three and a half years of work, Wyatt claimed to have found the ark in a subterranean cave, along with the Table of Shewbread, the Golden Altar of Incense, the Golden Censer, the seven-branched candelabra, a very large sword, an ephod, a miter with an ivory pomegranate on the tip, a brass shekel weight, numerous oil lamps, and a brass ring. The site also reports: “On the back of the Ark is a small open cubicle which still contains the ‘Book of the Law’ and is presumably the one Moses, himself, wrote. Ron found the Scrolls, written on animal skins, to be in perfect condition.”

Wyatt himself was reportedly never able to retrace his steps, and few scholars, if any, have accepted Wyatt’s claims. A preface posted on his Web site in a section about Wyatt’s search for the Ark of the Covenant sums up the problems involved with his claims. Written by Richard Rives, president of Wyatt Archaeological Research, it states: “Ron’s account of his discovery of the Ark of the Covenant cannot be confirmed and … recent exploration reveals unexplained discrepancies in that account.… Ron had no second witness and provided no conclusive evidence as to the location of the Ark of the Covenant; therefore, his account … makes perfect sense from a Biblical standpoint but it is not yet a proven fact.” As of this moment, it remains to be seen whether Wyatt’s claims will ever be proven.

Removed by Manasseh—In 1963, Menahem Haran, a respected biblical scholar at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, suggested that Manasseh, King of Judah during the early seventh century B.C., may have removed the ark when he set up a statue of Asherah and pagan altars in the Temple (II Kings 21:4-7; II Chronicles 33:4-7).

The problem with this theory is that it makes little sense even if the biblical account is followed in total. First and foremost, the ark itself is never mentioned in the biblical passages connected with Manasseh. The Bible says only that Manasseh set up both an idol and pagan altars in the Temple. It says nothing about him removing the ark; that he might have done so is simply a hypothesis formulated by Haran.

The Book of II Kings 21:4-7 states: “He built altars in the house of the Lord.… He built altars for all the host of heaven in the two courts of the house of the Lord.… The carved image of Asherah that he had made he set in the house of which the Lord said to David and to his son Solomon, ‘In this house, and in Jerusalem, which I have chosen out of all the tribes of Israel, I will put my name for ever.’ ” (See also II Chronicles 33:4-7.) However, after Manasseh had been carried off to Babylon by the Assyrians and subsequently returned to Jerusalem, the biblical account simply says, “He took away the foreign gods and the idol from the house of the Lord, and all the altars that he had built on the mountain of the house of the Lord and in Jerusalem, and he threw them out of the city” (II Chronicles 33:15).

The ark is, once again, not mentioned in these passages, and yet surely it would have been had Manasseh moved the ark out in the first place and then brought it back in once he removed the idol and the altars. Either way, this is a quintessential example of an “argument from silence,” which is always a dangerous type of argument to base a hypothesis on.

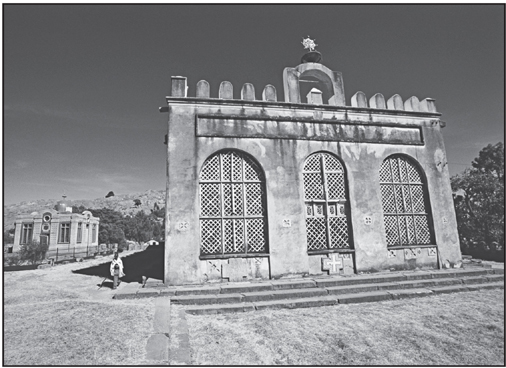

According to Ethiopian lore, the ark was brought from Jerusalem by Menelik I to Ethiopia, where it is alleged to reside at this Coptic church, Our Lady Mary of Zion, in Ahum. (Illustration Credits 6.6)

Ethiopia—One of the most popular theories today suggests that the ark is in Aksum, Ethiopia. The tradition originates in a story—really, a legend—related in the Ethiopian Kebra Nagast (Book of the Glory of Kings). The book’s origins are unclear; many scholars believe it was written in the 14th century A.D., but some say it could have been written as early as the 6th century A.D.

According to this tale, Solomon and Sheba had a son named David (but later more commonly referred to as Menelik I). David, or Menelik I, visited his father in Jerusalem, and upon departing for Ethiopia, took the ark with him to Aksum. There are numerous versions of this tale, each concerned with a different place the ark stopped before completing its journey to Aksum. It is now reportedly kept in a treasury near the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, but its actual presence there cannot be confirmed, for only the head priest of the church is allowed inside to see it.

The idea that the ark is in Aksum, Ethiopia, was resuscitated in 1992 by Graham Hancock, a former journalist who used to write for the London Economist. In his book The Sign and the Seal: The Quest for the Lost Ark of the Covenant, Hancock combines Haran’s suggestion that the ark was removed from the Temple during the reign of Manasseh with the Ethiopian legend recorded in the Kebra Nagast. Hancock suggests that Menelik and his party did not take the ark from Jerusalem; instead it was removed from the Temple during the reign of King Manasseh, subsequently taken to Egypt, where it made its way to Elephantine Island, and eventually ended up in a church in Aksum, Ethiopia.

Hancock’s theory was not universally well received by scholars, but it received much media attention and airplay on cable television. One proponent, however, was Bob Cornuke, the private investigator turned biblical investigator whom we have met in previous chapters. Cornuke essentially retraced Hancock’s steps to see whether he agreed with the theory, but Cornuke’s book is more of a first-person adventure story and makes Hancock’s volume seem almost scholarly by comparison.

There are a number of problems with these hypotheses that state that somehow the ark was moved from Jerusalem to Aksum, Ethiopia. Nevertheless, these problems pale in comparison to the fact that there is no way to test Hancock’s (and Cornuke’s) ultimate conclusion, since no one in recent years has been able to enter the building in Ethiopia that supposedly houses the Ark of the Covenant.

When Hancock’s book was first published, however, an article in the Los Angeles Times quoted Edward Ullendorff, a retired professor of Ethiopian Studies at the University of London as saying: “I’ve seen it. There was no problem getting access when I saw it in 1941.… They have a wooden box, but it’s empty.… Middle to late medieval construction, when these were fabricated ad hoc.” Ullendorff’s statement seems enough to quash the speculation generated by Hancock’s and Cornuke’s expeditions, but the final word debunking their Ethiopian hypothesis was published posthumously in 2005 by noted Ethiopian scholar Stuart Munro-Hay in his book entitled The Quest for the Ark of the Covenant: The True History of the Tablets of Moses, in which Munro-Hay systematically addressed each of the points raised by Hancock and ultimately concluded that it was not the original Ark of the Covenant that lay within the building at Aksum.

Mount Nebo—In 1981, Tom Crotser, founder of the Institute for Restoring Ancient History, led an expedition to find the ark just months after the movie Raiders of the Lost Ark had been released. He followed the reference in II Maccabees 2:1-5 that claims Jeremiah hid the Ark of the Covenant on Mount Nebo in Jordan. In his search, Crotser also relied upon the notes and drawings of an earlier American explorer, Antonia F. Futterer, who had searched for the ark in that area in 1927. On October 30, 1981, Crotser and his team announced that they had found the ark, which they described as a gold-covered rectangular box, in a cave on Mount Pisgah (Mount Nebo), and that they had taken numerous photographs.

The story was picked up by UPI and was published in newspapers across the United States. Many scholars were skeptical because Crotser and his group had previously claimed to have found Noah’s ark, the Tower of Babel, the city of Adam, and the great stone of Abel. Biblical Archaeology Review magazine asked the eminent archaeologist Siegfried H. Horn, a professor at Andrews University, to investigate Crotser’s claims, and then published a story about Crotser and his findings.

Horn reported that, of all Crotser’s pictures, only two showed anything; the rest were blank. Of the two pictures, Biblical Archaeology Review said, one “is fuzzy but does depict a chamber with a yellow box in the center. The other slide is quite good, according to Horn, and gives a clear front view of the box.” Horn also noted, however, that there was a nail with a modern looking head in the upper right corner of the face of the box and that the metal of the box appeared to be machine-worked. In his opinion, whatever it was that Crotser had found was not an ancient artifact, and was therefore not the Ark of the Covenant.

Dead Sea Region—Vendyl Jones, a longtime enthusiast of biblical archaeology from Texas and founder of the Vendyl Jones Research Institute (VJRI), linked together three sources to formulate the hypothesis that the ark was hidden, not on Mount Nebo, but on the other side of the Dead Sea in the caves at Qumran, which also held the famous Dead Sea Scrolls. Jones linked the reference in II Maccabees, which states that Jeremiah hid the Ark of the Covenant, with the famous Copper Scroll that was discovered in Dead Sea Scroll Cave 3 and a previously unknown rabbinical text called Emek Ha Melek (Valley of the Kings), which was supposedly first published in 1648 by Rabbi Naftali Ben Ya’acov Elchanon. Using these sources, Jones claimed the ark was hidden in a “Cave with Two Columns, near the River of the Dome” and began a series of explorations and excavations in the region near Qumran.

At Qumran in April 1988, Jones and his team claimed they had found the Shemen Afarshimon—the holy anointing oil—from the Temple. In 1992, Jones also claimed to find 600 pounds of reddish organic material that he said was a compound of eleven ingredients found in the holy incense from the Temple. In both cases, scholars met his claims primarily with skepticism. Then, in 2005, he was quoted as saying that the Ark of the Covenant would be discovered by August 14 of that year (on Tisha B’Av, a day of mourning in the Jewish tradition). He did not discover it by that date. Later, a correction was posted on his Web site, stating that he had been misquoted and that he had actually said “it would be very appropriate if he could discover the Ark by Tisha B’Av.”

Egypt (Valley of the Kings)—Using the same three sources as Vendyl Jones, Andis Kaulins, a German lawyer with a law degree from Stanford University, claims that Jeremiah hid the ark and that now it lies in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt, specifically in the tomb of King Tutankhamun. In fact, he claims that the portable chest with accompanying poles found in King Tut’s tomb, which we mentioned earlier, is not only similar to the ark, it is the Ark of the Covenant.

Kaulins’s claims, as far as I can tell, can only be found on the Internet. He is apparently the owner and operator of four Web sites and nearly fifty Internet blogs that feature topics ranging from archaeology to law, golf, and museums. Kaulins’s own Web site states that he is “the best in the world—ever—at what I do, which is decipherment work.” However, he never addresses the most important question of all: How did the ark get all the way to Egypt and into the tomb of King Tut, in light of the fact that Tut died toward the end of the 14th century B.C., more than 700 years before the time of Jeremiah?

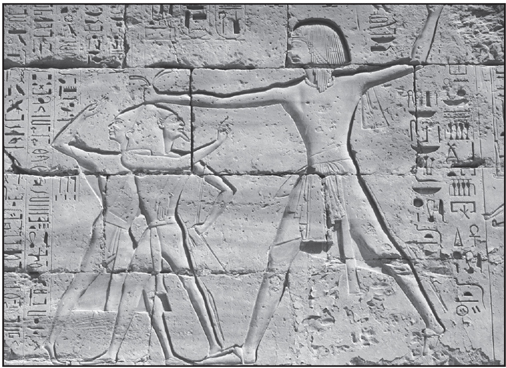

Carried off by Shishak—There is a reference in I Kings 14:25-26 that reads: “In the fifth year of King Rehoboam, King Shishak of Egypt came up against Jerusalem; he took away the treasures of the house of the Lord and the treasures of the king’s house; he took everything.” (See also II Chronicles 12:2-9.) This looting would have taken place about 925 B.C. and is probably the same invasion that is recorded by the Pharaoh Shoshenq on the wall of the Temple of Amon at Karnak in Egypt.

It is quite possible that Shishak carried off the Ark of the Covenant at this point, since it was the first time after Solomon’s rule that the city of Jerusalem had come under attack. Moreover, it would explain why the ark was never mentioned again in the biblical account, for the event occurred within a few years of Solomon’s death.

This is known as the “Indiana Jones” theory, since the hypothesis that Shishak had taken the ark back to Egypt, and specifically to the site of Tanis, was the underlying premise of the 1981 film Raiders of the Lost Ark, created by Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. Few scholars seriously believe that Shishak actually carried off the ark, however, and not just because the biblical account fails to mention such an event. There is also no mention of the ark in any of Shoshenq’s own inscriptions or in any traditions in Egypt dating to that period. Moreover, the primary Egyptian inscription written by Pharaoh Shoshenq detailing his campaign in Canaan—the account carved into the wall of the Temple of Amon at Karnak—does not seem to mention Jerusalem. There are also no other extra-biblical inscriptions to corroborate the biblical account that Shishak even attacked Jerusalem, let alone captured it.

Pharaoh Shoshenq left an inscription recording his campaign in the lands of Israel and Judah after the death of Solomon. (Illustration Credits 6.7)

Nevertheless, Michael S. Sanders, the self-taught “Biblical Scholar of Archaeology, Egyptology and Assyriology” we met earlier, says that Shishak carried off the ark, but that “its secret burial site could be at a terrorist stronghold on the West Bank.” Once again enlisting the use of NASA satellite images, as he did in his quests to find the Garden of Eden, Noah’s ark, and Sodom and Gomorrah, as well as documents in the British Museum and elsewhere, Sanders suggests that the ark is buried near a village called Djahiriya in the Judean hills, in an area reportedly known as a Hamas training ground.

Sanders says, “It is in very dangerous territory, but it must be worth the risk. We believe that we may have found the configuration of an Egyptian temple and it is under there that we will dig for the Ark. There will be archaeologists with us, but the search for the Ark is bound to be more of a treasure hunt than a classical archaeological dig.” That statement is enough to send shivers up a professional archaeologist’s spine, regardless of where the site is located or what modern facilities might be built above it today. Fortunately, Sanders hasn’t “yet received permission to start an excavation.” If and when he does, let us hope that it is less like a treasure hunt and more like a typical archaeological dig, just in case anything important is actually found.

We should also remember that in addition to Shishak’s raid, there are at least three other instances in which the Temple might have been looted between the time of Solomon and Nebuchadnezzar. As we noted earlier, if either Hazael, Jehoash, or Sennacherib succeeded in looting the Temple (rather than being bought off via a bribe), then the ark could have disappeared in either 800, 785, or 701 B.C., rather than in the more commonly suggested years of 597 or 586 B.C. at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar. However, as Herbert G. May, professor of Old Testament language and literature at the Oberlin Graduate School of Theology (and a participant in the University of Chicago’s excavations at Megiddo), wrote in 1936:

That the Jerusalem ark still existed at the time of Josiah is hardly to be doubted. The fact that it is not mentioned in the account of the sack of the Temple in 586 B.C. is insufficient reason for assuming that it must have disappeared earlier at the time when Shishak sacked the Temple of its treasures in the reign of Rehoboam, or when the wealth of the Temple was seized at the time of Asa and Ben-Hadad, or Amaziah and Jehoahaz, or Ahaz and Tiglath Pileser. If the ark did disappear before 586, it would seem to have done so between 621 and 586.

Destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar—Among the most likely hypotheses—but one that is not followed by most enthusiasts because it would mean the ark is lost forever—is that Nebuchadnezzar and the Neo-Babylonians destroyed the Ark of the Covenant during their destruction of the Temple in 586 B.C. The apocryphal Book of II Esdras 10:20-22 implies that the ark was either destroyed or looted by the Neo-Babylonians (“Our sanctuary has been laid waste, our altar thrown down, our temple destroyed … the ark of our covenant has been plundered”), and the rabbinical authorities in the Talmud (Yoma 53b–54a) further debate this possibility.

The fact that there is no mention of the ark either among the objects carried off by Nebuchadnezzar or subsequently returned by Cyrus the Great (see II Chronicles 36:7, 10, 18-19 and Ezra 1:7-11) strongly suggests that the Neo-Babylonians are more likely to have destroyed it than carried it off. Of course, we could also argue using some of the sources we mentioned earlier that the ark was no longer in the Temple by the time the Neo-Babylonians destroyed the building, so even this suggestion is hypothetical, but it is also entirely possible.

THE ARK OF THE COVENANT can be framed within the context of the entire history of the Israelites and the Judeans, from the time of Moses in the 13th century B.C. (or the 15th century B.C., as we have mentioned) through the capture of Jerusalem, the destruction of the Temple, and the Babylonian Exile in 586 B.C. How much of this grand sweep of history we include in our study depends upon when we believe the ark disappeared. At the very least, we should include the last part of the journey from Egypt (that is, the final stages of the Exodus, after Moses received the Ten Commandments); the entire period of the Israelite conquest of Canaan; the entire period of the Judges and the United Monarchy of David and Solomon; and part, if not all, of the era of the Divided Kingdoms of Israel and Judah. In short, we could write a book on the entire history of ancient Israel and Judah, as told from the point of view of the Ark of the Covenant.

As a result, it is out of the question to discuss its complete historical context, as we have done with previous mysteries (and will do with the Ten Lost Tribes in chapter 7). What we can do, however, is point out that the creation of the ark is integrally connected to the story of the Exodus, and its early history is tied to the Israelite conquest of Canaan, whose historical context we discussed in chapters 4 and 5. And the final part of its history, up to the point where we essentially lose sight of it in the Temple, is directly linked to the reigns of David and Solomon.

Thus, we should mention here that David and Solomon themselves, and their territorial expansions, have been severely called into question over the past decade or more. The biblical minimalists such as Niels Peter Lemche, Thomas L. Thompson, Philip R. Davies, and Keith W. Whitelam, all now either at the University of Copenhagen or the University of Sheffield, were especially vocal early on, with some even suggesting that David (and perhaps Solomon as well) never even existed and were simply figments of later writers’ imaginations.

Such extreme suggestions were silenced when fragments of an inscription mentioning the “House of David” (Beit David in Hebrew) were discovered at the site of Tel Dan in northern Israel in 1993 and 1994. The debate continues today, however, as to the extent of David’s and Solomon’s kingdoms: Did they in fact rule over a huge empire that stretched from the Euphrates to Egypt, as the biblical account suggests (I Kings 4:21), or were they simple tribal chieftains whose exploits were exaggerated by the later biblical writers?

We will not deal with this debate here, because it is still evolving and will ultimately be decided by additional archaeological excavations and further interpretations of new data being found at sites from Jerusalem to Megiddo and beyond. But we can suggest that any future discussions of the Ark of the Covenant may need to take into account the new positions reached by archaeologists, ancient historians, and biblical scholars concerning the reigns of David and Solomon, because it is clear that just as the early days of the ark are intertwined with the lives of Moses and Joshua, so are its middle days intertwined with the lives of David and Solomon.

TO MY KNOWLEDGE, not a single professional archaeologist has ever gone in search of the Ark of the Covenant. To their credit, however, amateur enthusiasts have been exhaustively searching for the ark everywhere that ancient literary sources suggest it might be: underneath the Temple Mount, on Mount Nebo, near Qumran, in Ethiopia, in Egypt, in the West Bank, or simply somewhere else in Jerusalem. There is not a single possibility that they have not investigated or speculated about, though all to no avail.

The problem does not usually reside in the locations for the ark that the enthusiasts suggest, because almost all of them are faithfully following at least one literary source. The rabbis looking beneath the Western Wall in Jerusalem followed the Babylonian Talmud and the Mishneh Torah. Tom Crotser followed II Maccabees, as did Ron Wyatt, although Wyatt also used other late and dubious sources as well, such as the Paralipomena of Jeremiah. Vendyl Jones followed II Maccabees, plus his interpretation of the Copper Scroll and the mysterious rabbinical text Emek Ha Melek, supposedly published in 1648. Andis Kaulins used the same three sources that Jones did. Graham Hancock and Bob Cornuke followed the Ethiopian story told in the Kebra Nagast, combined with an interpretation of the biblical accounts concerning Manasseh, first suggested by scholar Menahem Haran. And Michael Sanders followed the account in I Kings.

Where most of them have gone wrong, however, is in overstating their claims and conclusions, especially if they claim to have found the ark. In almost every single instance, their claims are not backed up by proof, or by any indisputable evidence for that matter. Kaulins’s theory has chronological problems. Crotser’s pictures are blurry and apparently show a modern nail in his ark. Nobody, including Ron Wyatt himself, has been able to retrace his steps to locate the ark again. Nobody has recently been able to get into the building in Ethiopia to see if Hancock and Cornuke are right. Nobody has been able to get under the Temple Mount to confirm the rabbis’ story. Nobody has received permission to dig at the West Bank site to verify Sanders’ theory. And no scholars were surprised when Vendyl Jones failed to find the ark by August 14, 2005.

Since no one has seen the ark since at least Josiah’s time, I would venture to say that it is no longer in existence. In fact, if I had to really guess, I would argue that it was melted down or otherwise destroyed, certainly by the time of Nebuchadnezzar, if not long before. The only other conceivable possibility I see is that the ark is hidden or buried somewhere underneath the Temple Mount, but I think it is more likely that it was destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar’s army in 586 B.C.

At a recent family reunion, a cousin I hadn’t seen in 25 years came up to me and earnestly asked, “Is the Ark of the Covenant located underneath the Temple Mount, as the Talmud says?” When I told him that it probably was not, his face fell. I hastily amended my statement and said that while it probably wasn’t there, there was no way to really tell until archaeologists could do further digging and exploration, which wouldn’t happen in the foreseeable future. That seemed to make him happier, and we proceded to talk about other topics.

It is now time for us to move on and try to locate the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. It might be easier to find them than the Ark of the Covenant … but then again, it might not.