12. The House That Love Built

Scarlet flounced into the kitchen after the visitors had left. She announced she was calling an extraordinary meeting of the festival committee and dialled the number of the Colour Patch Café.

‘Saffron, Perry, you’re coming with me,’ she said.

Perry didn’t feel like thinking about the festival and Saffron wanted to stay with her daddy, but when Scarlet was in a flouncing mood, no-one argued with her.

The wind howled, the blue tarpaulin flapped miserably and Ben disappeared into his shed. He sat in the Seat of Wisdom, pulled the lever that made the once-upon-a-time dentist’s chair recline, and stared up through the skylight, trying hard to see things that weren’t there. Things like the finished extension to the house. For months and months, he had been able to picture exactly the way it would look when it was finished. But today Ben could only see what the visitors had seen: a dripping blue tarpaulin over a timber frame — and he blamed himself. He should have finished by now. If he had, maybe the visitors wouldn’t have noticed all the things that weren’t quite right. Maybe they would have let Nell come home.

But like everything else he’d made, Ben wanted this building to be special. Each piece of material had to have meaning. Nothing was shop-bought. He had found the pieces, waited for them, bargained for them, worked for them. His shed was cluttered with the precious objects he had collected: panelled doors, slate shingles, church windows and chandeliers. And in the feed shed was a truckload of straw bales for the walls. But the slate shingles were the last thing Ben had found and without a roof to shelter them from the weather, straw bales cannot be laid. He closed his eyes to block out the greyness.

Ben might not have finished the extension, he might have been blinded by disappointment that afternoon, but he need not have been. Slowly but surely the elephants were moving on. There was a streak of sunlight on the Silk Road, an echo of hope in the hills. Ben’s children had learnt from him to see things other people could not.

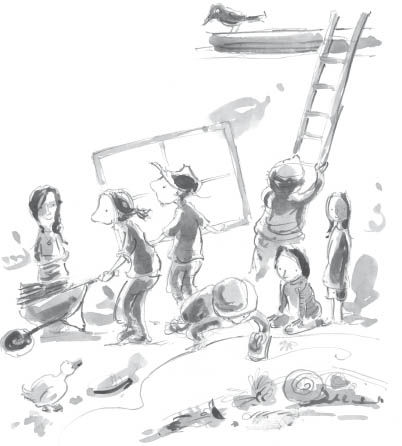

On Saturday morning, the rain had stopped and Jack Frost cloaked the paddocks with glisten and glimmer. Visitors arrived at seven o’clock. But this time they came in a bus towing a trailer, driven by Mr Davis. They brought picks, shovels, hammers, nails, paint, brushes, ladders, a cement mixer and a portable barbecue.

Uncle Tansil and his sisters, Shim and Janda, were in charge of breakfast. Mr Fairchild supplied sausages and bacon, Nell’s girls provided eggs and Annie had made the bread. By morning-tea time, Annie had painted a large blue square on the floor in the front room. After lunch, she added painted pink cabbage roses and a knotted cream fringe around the border. It was an amazing un-trip-over-able carpet square.

Grandma Mosas, whose husband had been a shoemaker, brought a cobbler’s awl and long thin strips of leather and she mended the tear in the red vinyl couch, so the stuffing could no longer escape.

Teddy Wilson and the preacher made a concrete path. Indigo arranged chips of pretty china spelling ‘secret garden’ in the wet concrete and Griffin, Perry and Layla decorated it with handprints and patterns made with pebbles. Annie thought the handprints were such a good idea she asked everyone to do the same.

The path was plenty wide enough for The Intrepid, but the men had been under strict instructions not to make it straight. It meandered like a stream, beside the rhubarb patch, past the marigolds, under the honeysuckle arbour, around the lilac tree, next to the butterfly bush and through the gate, to the orchard.

By sunset, the roof of the extension had been slated and guttered, the window frames, downpipes and doors had been fixed in place. Mr Elliott, his son, Patrick, and Uncle Tansil had wheelbarrowed all the straw bales from the feed shed and stacked them in the middle of the room, ready for fitting into the wall spaces, and the frame was completely enclosed by the blue tarpaulin. The thing that only Ben had been able to imagine for so long was now becoming visible to everyone.

Scarlet had made another roster. Now there were three. The festival roster, the visiting Nell roster and the building roster. The following morning, the bus arrived again. This time with a different group of passengers. And so it went on. The bus only came on weekends, which was when most people had time to spare, but on weekdays there were other people who came in ones or twos or threes in cars or on bicycles or motor scooters. Every time someone visited Nell, she would tell them how much she wanted to come home. But Ben had made them promise not to tell her about the unwelcome visitors and what they had said.

Then came inspection day. Barney was locked in the feed shed, which he didn’t mind at all. Blue was wearing his best bow-tie and Annie had reminded Ben to comb his whiskers. The Silk family waited outside. Zeus perched on the shed, like a weather vane, and squawked when he heard the distant hum of a vehicle turning off the main road.

Saffron ran down the hill. The puddles were drying up. She opened the gate and climbed up on the strainer post. When the vehicle got as far as the dip in the road near Canning’s orchard, she could see its roof. She jumped down and ran back to the others.

‘It doesn’t look like the car they came in the first time,’ she said.

‘It doesn’t sound like a car either,’ said Griffin.

Then they saw it — Mr Davis’ bus — chugging slowly towards the gate and up the hill. The door swung open and the passengers disembarked.

‘We thought you might like company,’ grinned Teddy Wilson, looking very impressive in his policeman’s uniform.

‘Thirty-seven!’ said Violet, who had been counting as the townsfolk lined up beside the Silks, waiting for Daryl and Cynthia to arrive.

It was Annie who explained to the visitors that the slate shingles had been salvaged from Pearl Brady’s cottage before developers built a block of apartments on the site. She told them how the windows had come from the small suburban church where Nell and Johnny were married. She pointed out the rosy carpet square, now hanging on the wall, and told them how it had belonged to Nell’s parents — that its thinness was due to three generations of children dancing on it. And when they went outside, Annie showed them the handprints in the concrete path, one for every person who helped Ben make his dream come true.

But the visitors had a job to do. They inspected, checked boxes and wrote a report. Then they looked at the proud faces of the butcher, the lady from the post office, the policeman, the refugee family, the preacher, the bus driver, the doctor, the cemetery caretaker, the school teachers and the children. And this time the visitors stayed for afternoon tea, warmed and welcomed by walls as curved and cream as angels’ wings. Around and above them tree-trunk posts and beams held everything in place like everlasting arms. Cynthia and Daryl gazed out through a wall of five church windows and watched the glories of winter from the house that love built.