The pike, a poled weapon, was the longest pole arm and was widely employed in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period, especially the 17th century when massed pikemen protected musketeers against cavalry attack while the musketeers were reloading. The standard length for the spear-shaped pike was 16 feet, which is as long as the sarissa employed in the Macedonian phalanx during the 4th century BCE. Some pikes were as long as 22 feet, and others were shorter, cut down by the soldiers who wielded them to make them easier to carry. The head of the pike was of iron, but owing to the great length, its shaft was of a strong wood, often ash, reinforced with two steel strips down the sides.

Pikes were inexpensive to make, and soldiers required little training in their use. The great length of the pike made it unwieldy for close combat, however. As a consequence, pikemen often carried swords to use if their ranks were broken. Pikes were employed en masse, in large hedgehog phalanx formations, the pikes projecting in the direction of an anticipated cavalry attack. Cavalry was the offensive arm, while pikemen were the primary means of defending against it. The pike reached its greatest effectiveness in the Spanish tercio formation, which employed pikemen in the center and harquebusiers on the flanks.

The pike proved unwieldy and ineffective in the woodlands of North America and was soon largely discarded there, but it remained in service in Europe until the advent of the bayonet and the improving effectiveness of the musket. A bayonet attached to the muzzle end of a musket made every musketeer his own pikeman. Pikes survived only as symbols of authority and were often used to carry regimental colors.

Further Reading

Blackmore, D. Arms & Armour of the English Civil War. London: Royal Armouries, 1990.

Foulkes, C., and E. C. Hopkinson. Sword, Lance and Bayonet. London: Arms and Armour, 1967.

Type of sailing ship. By the end of the 12th century, twin-masted (mainmast and foremast) lateen-rigged ships were common in the Mediterranean. In Northern Europe, twin-masted ships also appeared in the early 15th century but with the addition of a third, after or mizzen, mast. This ship type was known in England as a carrack, in France as the caraque, in the Netherlands as the kraeck. The term is believed to have derived from Arabic.

Mary Rose

The Mary Rose was an English carrack. Constructed at Portsmouth in 1509 and named for King Henry VIII’s sister Mary and the Tudor rose, it weighed some 700 tons, was 147 feet in overall length by 38 feet 3 inches in beam, and mounted 81 guns.

The Mary Rose served as the English flagship in Henry VIII’s wars against the French in 1522 and 1536. In the course of the third war in 1545, the French sent a large number of ships to Portsmouth. Preparing to meet the French on July 19, the Mary Rose took aboard a large number of soldiers. The ship’s normal crew was 415 men, but there may have been 700 men on board that day, many in armor and most of them on the main and castle decks. This extra weight high in the ship, combined with the ship’s high bow and after-castle and weighty cannon there, made the Mary Rose unstable. Sailing out with other English ships against the French, the Mary Rose caught a light wind and suddenly heeled over. Water then rushed in through the ship’s open gun ports, and it went down.

The wreck in the Solent was rediscovered in 1968, and what remained was raised in 1982. The ship and its artifacts have proved to be incredible sources of information about the Tudor period. For instance, 137 longbows and 3,500 arrows were recovered, the only ones to survive from that period. The ship and its contents are today displayed in a special museum at the Portsmouth Naval Base.

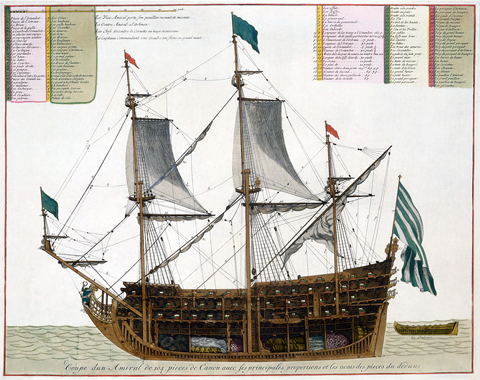

Woodcut of an armed Genoese carrack, a European ship type that predominated from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries. (Historical Picture Archive/Corbis)

The carrack predominated in Europe from the 14th to 17th centuries. The earliest types had a rounded stern in a carvel-built hull (planks flush rather than overlapping). The ships were rigged with square sails on the fore and mainmast and a lateen sail on the mizzen. A centerline ladder led to the round top of the mainmast. By the 16th century, the carrack had become a larger vessel of up to 125 feet in overall length by about 34 feet in beam. It also gained a fourth mast aft: an extra mizzen, known as the bonaventure mizzen or bonaventure for short.

Traditionally, in time of war merchant ships were simply fitted out to carry weaponry. With the introduction of gunpowder weapons at sea in the 14th century, the carrack’s armament might range from as few as 18 small guns to as many as 56, some of them placed in the tops of the masts (the “fighting tops” as they became known). The carrack had considerable advantage as a gunship over the rowed galley, which mounted only a few guns forward. Because fighting at sea was very much like that at land, the higher structures fore and aft, which might actually be built up in time of war to gain height advantage, were known as the castles: the forecastle and aftercastle.

Further Reading

Howard, Frank. Sailing Ships of War, 1400–1860. New York: Mayflower Books, 1979.

Kihlberg, Bengt, ed. The Lore of Ships. New York: Crescent Books, 1986.

Landström, Björn. The Ship: An Illustrated History. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1961.

A revolutionary 16th-century vessel, the galleon was a large sailing ship that offered great improvements over the earlier carrack and was widely adopted by the navies of Western Europe. The term “galleon” itself has become virtually synonymous with any vessel of the late medieval/early modern period, even though it was a Spanish term for a particular type of ship. The word “galleon” comes from the Latin galea (galley) through the Old French galion.

Despite the Spanish name, galleons were developed and first constructed in England during the later 16th century based on experiments by Sir John Hawkins. While the English did not call these ships galleons, they did develop the ship’s layout. The hull featured a high, squared stern and a low forecastle set back from the stem with a prominent beakhead just above the waterline, which gave the vessel its characteristic shape and facilitated ramming. The hull was both long and slender and carried multiple masts. It sat higher above the water and was faster and easier to navigate than earlier vessels designed for the same purpose.

The Golden Hinde under sail. The ship is a reproduction of the galleon employed by Sir Francis Drake to circumnavigate the globe during 1577–1580. (Joel W. Rogers/Corbis)

Galleons could be heavily armed. Rows of gun ports were cut into each side of the galleon’s hull. It had been discovered much earlier in the 16th century that by cutting out ports and placing guns beneath the main deck, a ship could carry many more guns of a greater weight without destabilizing the vessel. Guns were also placed in positions that enabled them to fire directly ahead or astern the galleon. The typical Elizabethan galleon carried some 50 guns of various sizes and had a crew of some 250 men. It was approximately 135 feet in length (keel of 100 feet) and 38 feet in width. An example of the galleon is the English Revenge of 1577.

The galleon design proved superior to previous ships, and its use spread throughout Western Europe. Spain also built 20 galleons to participate in the armada sent against England in 1588. The galleon continued to be a mainstay in Western navies for years thereafter and established the basic design for the great ships of the line that would follow it.

Further Reading

Cipolla, Carlo M. Guns, Sails, and Empires. New York: Pantheon Books, 1965.

Kemp, Peter, ed. The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Rodger, N. A. M. The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain, Vol. 1, 660–1649. London: HarperCollins, 1997.

For 2,000 years until the appearance of cannon in the 14th century, the principal object at sea was to close with an opposing vessel and destroy it by ramming or take it by storm. The introduction of gunpowder artillery changed that.

Early naval cannon were small, averaging 20–40 pounds in weight, and were essentially man killers, part of an antipersonnel arsenal that included bows, crossbows, swords, pikes, cutlasses, and spears. They probably resembled the bombards used ashore—short weapons with wide bell mouths—and were probably positioned in a ship’s rails. Later guns were made longer and heavier. The advent of heavy guns aboard ship meant that it was possible to stand off and engage an enemy vessel without actually having to close with it. Soon cannon became a warship’s raison d’être, exercising tremendous influence on ship design.

The first use of guns at sea is unknown, although there may have been a few in the Battle of Sluys on June 24, 1340, during the Hundred Years’ War between France and England (1337–1453). They were definitely employed on warships in 1376 when the Venetians bombarded the ports of Zara and Cattaro.

The earliest naval guns were breechloaders. They did not have to be hauled back into battery after firing and could thus be reloaded more quickly than muzzle-loaders. They could also be worked with fewer men. The basic problem with early breechloaders was the lack of adequate sealing of gases at the breech and the danger this posed to crews during firing. Improvements in gunpowder also hastened the change to muzzle-loaders, which could withstand heavier charges.

Muzzle-loaders were cast in both bronze and iron. Bronze was favored because it stood the shock of discharge better than iron. If defective, bronze was more likely to bulge than burst, and it was easier to cast. Bronze guns could also be easily recast when worn. Iron was heavier—not the factor at sea as on land with field artillery—but was far cheaper by a factor of as much as 4:1, and cost won out. By the end of the 17th century, iron guns predominated in European navies.

Late-16th-century muzzle-loaders were of three basic types: culverin, cannon, and perier (petrero, pedrero, or cannon pedro). Culverins were the biggest and heaviest and could project shot the farthest. They were some 30 calibers (bore diameters) in length. Because of its bore-to-length ratio, the culverin was the predecessor of the modern naval gun. Cannon were perhaps 15–20 calibers in length. Periers (or “stone throwers”) were 16 to 8 or less calibers in length. These included petards, mortars, and howitzers. It is, however, quite impossible to categorize early guns. One source identified some 40 different types in 1588, and his is not an exhaustive list.

Guns were positioned in their carriage by means of lugs, known as trunnions, cast on the sides of the gun. The common ship carriage had four wooden wheels, or trucks. It was secured in place and moved about by stout rope breeching and tackle. The truck carriage remained little changed from the 16th to the 19th centuries.

Further Reading

Hogg, Ivan, and John Batchelor. Naval Gun. Poole, Dorset, UK: Blandford, 1978.

Padfield, Peter. Guns at Sea. New York: St. Martin’s, 1974.

Robertson, Frederick L. The Evolution of Naval Armament. London: Harold T. Storey, 1968.

Tucker, Spencer C. Arming the Fleet: U.S. Navy Ordnance in the Muzzle-Loading Era. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989.

Early cannon were hardly accurate. Gunners might sight along the barrel, but doing so gave a slight elevation because of the greater diameter of the gun at breech than the muzzle. Raised sights at the muzzle end helped compensate for this.

In the 16th century, however, the gunner’s quadrant appeared. Employed on land and sea, it enabled the guns of a battery to be laid all at the same elevation. Made of wood or brass and essentially a level, the quadrant was a long L in shape with a quarter circle marked in 10ths of degrees at the base of the L. The long arm of the quadrant was placed in the barrel, and a weighed plumb bob from the juncture of the L then provided a reading of the elevation by noting where the plumb line crossed the marks on the arc. At sea where a reading in degrees less than horizontal might be required, the quadrant might take the form of a full half circle at the end of the arm.

Although firing tables were soon developed that provided estimates of range depending on charge and elevation, firing was very inexact, and gunners preferred to operate at very close or point-blank range. Distant firing was very inexact, and the longer the range, the greater the possibility of error. Cannon powder could vary in power as much as 20 percent. The great windage (the difference between the diameter of the projectile and the diameter of the bore) of early guns also meant that the projectile bounced down the bore (known as balloting) and might leave the gun at any direction, determined by the last bounce before departing the muzzle. Projectiles also drifted in flight, depending on the wind and atmospheric conditions. It is little wonder, then, that firing at long range was referred to as “at random.”

With the advent of rifled breech-loading cannon and uniform production methods for projectiles and propellant, long-range indirect fire became more effective, which required very precise measurements of the tube’s angle of elevation. The modern gunner’s quadrant remains to this day an essential piece of fire-control equipment on the artillery pieces of most nations. The modern gunner’s quadrant is an adjustable clinometer that is placed on precision-machined pads on the breech of the gun and set to the desired angle. As the gun is elevated, the proper angle of elevation is indicated by the gunner quadrant’s leveling bubble. Modern gunner’s quadrants are calibrated in mils, with 17.777 mils to the degree.

Further Reading

Peterson, Harold L. Round Shot and Rammers. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole, 1969.

Tucker, Spencer C. Arming the Fleet: U.S. Navy Ordnance in the Muzzle-Loading Era. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989.

The kobukson (turtle) ships were the world’s first armored warships. Ordered constructed in 1591 by Korean admiral Yi Sun Sin to meet a Japanese threat from the sea, the first of these vessels was launched just days before the Japanese invasion of Korea in April 1592. Yi then trained his men in the new warships, which then played a leading role in the Japanese-Korean War of 1592–1598.

Sufficiently detailed descriptions of the vessels survive to provide a fairly complete picture of their appearance. They were about 116 feet in length and 28 feet in beam. They had a raft-like rectangular-shaped hull, a transom bow and stern, and a superstructure supporting two masts, each with a square rectangular mat sail. A carved wooden dragon head was set at the bow.

The ships were powered by both sail and oar, with openings for 8–10 oars on each side of the superstructure. The oars provided additional speed and maneuverability. The superstructure was protected by a curved iron-plated top that gave the vessel a turtle shell–like appearance. The iron plating had spikes set in it to prevent an enemy crew from boarding. The ships also mounted a number of cannon, six on each side and several at the bow and stern. The kobukson proved highly effective in combat with the Japanese.

A model of American David Bushnell’s submarine, the Turtle, employed against British in New York Harbor on the night of September 6–7, 1776. The model is at the Science Museum, London. (SSPL/Getty Images)

Further Reading

Galuppini, Gino. Warships of the World: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. New York: Military Press, 1989.

Turnbull, Stephen R. Fighting Ships of the Far East (2): Japan and Korea, 612–1639. Buffalo, MN: Osprey, 2003.

Frigates were important warships in the age of sail. Of obscure Italian origin, the term “frigate” was apparently first attached to certain small, fast British ships of the 1640s modeled on Dunkerque privateers. By the 18th century, the term “frigate” had come to mean a square-rigged medium-sized warship with broadside artillery on one full gun deck and lighter pieces on the forecastle and spar deck.

Frigates proved useful for a wide array of missions, including scouting, screening, raiding, and escorting merchantmen. In the Royal Navy of the era, frigates carried from 22 to 38 guns, generally 18-pounders. Early frigates usually displaced from 500 to 1,000 tons, were constructed of weaker hull scantlings than were ships of the line, and were manned by smaller crews (generally of 200 to 400 men). Hence, frigates were much cheaper to build and operate, although they were too weak to stand in the line of battle.

During the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815), British frigates often cruised on detached duty looking for enemy shipping. British frigates compiled an enviable record against their foreign counterparts, taking or destroying 235 enemy ships from 1793 to 1812 while losing only 6 of their own to hostile action. The successes of the large U.S. superfrigates, such as the 44-gun Constitution, proved especially shocking and led the Royal Navy to develop larger frigates of its own mounting 24-pounder guns.

The U.S. Navy frigate Constitution depicted saluting George Washington’s birthday during a port call at Malta in 1837. The Constitution, easily the most famous ship of the U.S. Navy, remains in commission at Boston and is the world’s oldest warship still afloat. (United States Navy)

With the introduction of steam propulsion in the mid-19th century, a number of navies built steam frigates, some large and powerful. For example, vessels of the U.S. Merrimack class displaced 4,650 tons and were armed with 40 8- and 9-inch shell guns.

Shortly after the American Civil War, the term “frigate” fell into disuse. With the introduction of armor plate, the successor to the frigate was dubbed the cruiser, a designation in common usage by the 1880s. Then in World War II, the classification “frigate” was resurrected for a quite different type of warship: the oceangoing antisubmarine escort. The first of these were the 27 ships of the River class (2,000 tons and 20 knots). Although they carried an armament (two 4-inch guns and 150 depth charges) quite similar to that of the new destroyer escort type, frigates were designed to the lesser mercantile standards. By the end of the war, British and Commonwealth yards finished another 157 ships of the Loch and Bay classes. The U.S. Navy constructed 98 similar vessels of the Ashville and Tacoma types (officially rated as patrol frigates).

Following World War II the term “frigate” mutated once again, with most navies continuing to use the classification for oceangoing escorts smaller than a destroyer. These could be sizable ships; some Soviet and British examples were as big as World War II large destroyers.

Beginning in 1955, the U.S. Navy reclassified its large destroyers (or destroyer leaders) as frigates, thereby commemorating the proud role that these warships had played in the early American sailing navy. The principal mission of these Cold War frigates was to escort fast carriers, and for that duty they carried extensive radar suites and antiaircraft missile batteries. Some of these ships were big, such as the 7,900-ton Belknap class or, at the extreme, the nuclear-powered California class of over 10,000 tons. In 1975, the U.S. Navy conformed to the more usual practice by reclassifying its frigates as cruisers and its oceangoing escorts (such as the Perry class of 3,500 tons) as frigates.

Further Reading

Gardiner, Robert. Frigates of the Napoleonic Wars. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000.

Lavery, Brian. Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men and Organisation, 1793–1815. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989.

Muir, Malcolm, Jr. Black Shoes and Blue Water: Surface Warfare in the United States Navy, 1945–1975. Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1996.

Tucker, Spencer C. Handbook of 19th Century Naval Warfare. Stroud, UK: Sutton, 2000.

Ships of the line also known as liners, battleships of the line, or line of battleships, were the largest and most powerful warships of the age of fighting sail. Such vessels were heavily armed, expensive, and complex and carried the greatest national prestige. They were so-named because, with up to 30 inches of wooden planking protection against enemy cannon fire, they were capable of standing in the main battle line that characterized fleet engagements of the time. Ships of the line were three-masted, square-rigged vessels of two to four gun decks. More than 200 feet in length and 50 feet in beam, they carried crews of 600–800 men. By way of illustration, HMS Victory is 227 feet overall (186 feet on the gun deck) and 52 feet in beam and displaces 3,500 tons. In 1805 it mounted 104 guns (30 32-pounders, 28 24-pounders, 44 12-pounders, and 2 68-pounder carronades).

The bigger the ship, the more expensive it was to build, and thus in 1789 a British 100-gun ship cost £24.10.0 per ton, a 74-gun ship cost £20.4.0, a 36-gun ship cost £14.7.0, and a sloop only £12.3.0. Conversely, larger warships were less expensive to maintain per gun than smaller vessels.

The Royal Navy ship of the line Victory of 1778 is the oldest warship in the world still in commission and one of the most famous museum ships. The first-rate three-deck Victory was laid down in 1759. Launched at Chatham in 1765, it was commissioned in 1778. Displacing approximately 4,000 tons fully loaded, it measures 328 feet overall, with a beam of 52 feet. Its mainmast is 203 feet tall. The Victory’s crew complement at the Battle of Trafalgar in October 1805 was 850 officers and men. Armament consisted of 30 32-pounders, 28 24-pounders, 30 12-pounders, 12 quarterdeck 12-pounders, and 2 68-pounder carronades.

The Victory participated in fighting against France and Spain in the American Revolutionary War and the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. After two years as a hospital ship and two years of refit, it was recommissioned in 1801. The Victory’s most famous action was undoubtedly as Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson’s flagship in the Battle of Trafalgar in October 1805. In 1922 the Victory was moved to Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, where it was dry-docked and then restored as a museum ship to its Trafalgar appearance. The Victory is still manned by an active-duty Royal Navy crew and flies the White Ensign of a commissioned Royal Navy ship.

By the time of the French Revolution the smallest ships of the line carried 64 guns, although there were those who believed the smallest that could effectively stand in the line of battle was one rated at 74 guns. The largest first-rate ships of the line mounted 120 guns, although a few could carry more. But the workhorse ship of the line at the end of the century was the 74. On the eve of the wars of the French Revolution three-quarters of French Navy ships of the line were 74s, with the remainder being those rated at 80 guns and the three-deckers.

At the turn of the century there was a trend toward larger ships of the line. The world’s only four-decker, the Spanish Santísima Trinidad, carried 136 guns. The largest ship in the Royal Navy at the end of 1793 was the French-built Commerce de Marseilles, a 120-gun behemoth taken during the British capture of Toulon in 1793.

Most navies possessed ships of the line, but the U.S. Navy had none in active service until after the War of 1812. The Independence, launched in 1814, was the first American ship of the line apart from the America, which was given to France upon its completion in 1782 and thus technically was never in U.S. service. The Pennsylvania, laid down in 1822 and completed in 1837, was the largest U.S. Navy sailing vessel and for a time the largest in the world. Originally designed for 136 guns, its initial armament was 16 8-inch shell guns and 104 32-pounders.

Although obsolete by the second half of the 19th century, the wooden battle ship of the line evolved into and gave its name to the steam-propelled steel-armored battleship.

The first-rate British ship of the line Victory, launched in 1765. The oldest warship still in commission, it may be seen at the Portsmouth Navy Yard in England. (Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis)

Further Reading

Howard, Frank. Sailing Ships of War, 1400–1860. London: Conway Maritime, 1979.

Lambert, Andrew. The Last Sailing Battlefleet: Maintaining Naval Mastery, 1815–1850. London: Conway Maritime, 1991.

Lavery, Brian. The Ship of the Line: Design, Construction, and Fittings. 2 vols. London: Conway Maritime, 1983.

Lavery, Brian, ed. The Line of Battle: The Sailing Warship, 1650–1840. London: Conway Maritime, 1992.

Mortars are high-angle–fire muzzle-loading weapons designed for plunging fire to surmount obstacles such as fortress walls. Mortars utilize explosive shell. Along with guns and howitzers, mortars form the triad of artillery types. The first mortars were short, only two to four times the diameter of the bore. Most were of bronze, although some were cast in iron. Mortars had powder chambers at the base of the bore for their powder charge. Cast with trunnions (pivot) at the base, mortars were usually fixed to fire at a 45-degree angle, with range determined by the amount of the powder charge. The charge was considerably less than that for long guns, as was the windage (the difference between the diameters of the bore and the projectile). Range was adjusted by varying the amount of the powder charge.

To fire the mortar, a set amount of loose powder was measured into it and positioned in the powder chamber at the base of the bore. A shell was then loaded into the mortar. The larger heavy-round projectiles might have a ring to facilitate their loading. The shell was positioned so that the fuze faced the top of the bore. Placing the fuze against the powder chamber might cause its malfunctioning on firing. If the fuze was toward the muzzle, it was lit by means of linstock or port-fire, just before the main charge was lit and the shell lofted into the air. Ultimately gunners learned that windage allowed some of the charge to escape around the shell and ignite the fuze. This greatly reduced the hazard for the gunners.

Mortars varied greatly in size. In the 18th-century British Army they ranged from the small 4.5-inch coehorn mortar that could be transported by two men in 5.8-, 8-, 10-, and 13-inch models for siege work.

The coehorn was named for its inventor, Dutch captain and later general Menno van Coehoorn (1641–1704). It was first employed in the siege of Grave in 1674. The mortar was subsequently widely used by the English, who called it the coehorn. Designed to direct plunging shell fire into an enemy works, it was set in a fixed wooden mount at 45 degrees elevation, with range adjusted by varying the amount of the powder charge. The British coehorn mortar of the late 18th and early 19th centuries was a 4.5-inch–caliber weapon, 13 inches in overall length. It weighed 86 pounds and could be transported by two men by means of carrying handles on each side of the wooden mount.

The British also apparently employed very small 2.25- and 3.5-inch mortars for projecting hand grenades, although these were not listed in official armament. The largest British mortar ever was a 36-inch built-up model intended for the siege of Sebastopol in the Crimean War (1854–1856), but it was completed too late for the war and remains at Woolwich Arsenal.

Mortars were also employed aboard ship for shore bombardment. They were carried aboard special vessels known as bomb ketches (or bombs). Sea mortars, even heavier than those commonly employed on land, were mounted on strong wooden beds and usually fixed at a 45-degree elevation. Commonly the beds turned on vertical pivots. Some mortars were fixed in place; these were turned by moving the ship, usually by springs attached to the anchor cables. Since most mortars were fixed in elevation, range was adjusted by altering the charge.

The most common sea mortars in the 18th- and early-19th-century Royal Navy and U.S. Navy were of 10- and 13-inch bore size. The 13-inch mortar was a formidable weapon; weighing 5 tons, with its maximum powder charge of 20 pounds it could throw its 196-pound shell as far as 4,200 yards in 31 seconds. During the American Civil War (1861–1865) the U.S. Navy employed this same size mortar, although of newer model, against Confederate land forts, especially along the Mississippi River, although with mixed result.

Further Reading

Caruana, Adrian B. The History of English Sea Ordnance, Vols. 1 and 2. Ashley Lodge, Rotherfield, East Sussex, UK: Jean Boudriot Publications, 1994, 1997.

Hogg, Ivan V. A History of Artillery. Astronaut House, Feltham, Middlesex, UK: Hamlyn Publishing Group, 1974.

Peterson, Harold L. Round Shot and Rammers. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole, 1969.

Tucker, Spencer C. Arming the Fleet: U.S. Navy Ordnance in the Muzzle-Loading Era. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989.

Bomb vessels were early shore bombardment vessels. The first bomb vessel may have been the French galiote à bombe. Based on the Dutch galeote or galliot, it was short in length and broad in beam and was an ideal gun platform. The French employed five of them to shell Algiers in 1682. These specially designed vessels were known in England as bomb ketches, bomb brigs, bombards, or bombs. In both the Royal Navy and the U.S. Navy, they were given names of volcanoes (such as Aetna and Hecla) or names that were expressive of their might (such as Thunder and Spitfire).

The ketch was a two-masted square-rigged vessel. Its mainmast was nearly amidships and had a course and square topsail and topgallant as well as a gaff sail. The mizzenmast carried the square sails of the ship and also a spanker. In appearance the ketch looked like a ship that was missing the foremast. This left the forward portion essentially clear for the mortar(s).

Bomb ketches were strongly built and fitted with more riders than any other vessel, a reinforcement needed to sustain the shock from the discharge of the heavy mortars they carried. Originally about 100 tons and 60–70 feet in length of deck, they were shallow-draft vessels requiring only about 8–10 feet of water, which allowed them to maneuver close to shore. Early-19th-century bomb ketches were larger—about 300 tons, 92 feet in length of deck, 27.5 feet in breadth, and 12 feet in depth of hold. When loaded, they drew about 12 feet of water.

The danger of explosions aboard bomb vessels led to special precautions in their construction. These included bulkheads of planks between mortars and magazines. During firing, square wooden screens were hoisted on a boom over each mortar to screen the flash, and wetted tarpaulins were lashed over the hatchways to the magazines.

Eighteenth-century Royal Navy bomb vessels were armed with one 13-inch and one 10-inch sea mortar. They also mounted eight 6-pounder long guns and assorted swivel guns in their rails for their own defense. By 1810, bombs in the Royal Navy carried two 10-inch mortars and four 68-pounder carronades. Later the 13-inch mortar came back into use, and the carronades were removed.

Bomb vessels were intended for shore bombardment only, not to fight other ships. The U.S. Navy employed them in fighting against Tripoli beginning in 1804 and during the Mexican-American War (when four bomb vessels each mounted a 10-inch columbiad). During the American Civil War, the U.S. Navy employed 13-inch iron mortars on schooners and small mortar boats.

Further Reading

Tucker, Spencer C. “The Navy Discovers Shore Bombardment.” Naval History 8(5) (October 1994): 30–35.

Ware, Chris. The Bomb Vessel: Shore Bombardment Ships of the Age of Sail. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994.

The howitzer is the third member of the artillery family. The last of the three to appear, it is a medium-trajectory weapon between the flat-trajectory cannon and the high-angle–fire mortar. The term “howitzer” is derived from the Dutch word houwitser and the German word haubitze. Descended from the perrier (stone thrower), the howitzer provided a bridge between the cannon and mortar. It is a comparatively short-barreled, relatively low-velocity weapon. As with the mortar, early muzzle-loading howitzers had a chamber smaller than the bore in order to hold the powder charge. Like the gun, the muzzle-loading howitzer had lugs (trunnions) cast on its sides near the balance point. Both the howitzer and the mortar were usually cast of bronze. The howitzer provided higher-angle fire than the flat-trajectory gun and was thus useful in reaching over terrain obstacles. It was also designed to fire explosive shell. Howitzers were also considerably lighter than long guns of comparable caliber.

Howitzers were first introduced in the late 16th century. Although in general use during the Napoleonic Wars, when they typically made up one-quarter or one-third of the tubes in each field battery, howitzers were especially favored by Frederick II (Frederick the Great) of Prussia (r. 1740–1786). Eighteenth-century British howitzers appeared in 8- and 10-inch bore sizes. Dahlgren boat howitzers in 12-pounder and 24-pounder sizes provided excellent service during the American Civil War.

At the beginning of World War I, the Germans fielded the mammoth Krupp 420mm (16.38-inch) siege howitzer, known as the “Big Bertha.” The British introduced a slightly smaller 15-inch howitzer in 1915. Perhaps the most famous modern howitzer was the U.S. 105mm of World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, which alongside the French 75mm gun of World War I was probably the most successful modern artillery piece. It was not withdrawn from service until the late 1980s. The M102 howitzer was a 105mm of completely different design, which served alongside the M-101A1 but never completely replaced it. Currently both the M-101A1 and the M-102 have been replaced in U.S. service by the British Royal Ordnance M-119 105mm gun.

Further Reading

Hogg, Ivan V. A History of Artillery. Astronaut House, Feltham, Middlesex, UK: Hamlyn Publishing Group, 1974.

Zabecki, David T., ed. World War II in Europe: An Encyclopedia, Vol. 2. New York: Garland, 1999.

The term “shell” is derived from the outer covering of shellfish and dates from at least the eighth century. The term came to be used for any carcass (hollow artillery round) filled with explosive powder and set off by a fuze. Shells may have been employed for the first time in warfare in 1588 when they were used by Spanish troops in the siege of Bergen-op-Zoom in the Netherlands. Shells were particularly effective against enemy troop concentrations and were also used in mortars with high-angle fire to bombard fixed fortifications. As early as 1644 in England there is reference to grenades as “small shells” filled with fine gunpowder.

The first shells were very dangerous to the artillerymen firing them. Because they were unreliable and often exploded prematurely, for the most part they were not used in long guns but only in very short weapons known as mortars that were only about twice as long as their bore diameter. Here the round shell could be inserted fuze up and then lit before firing. If inserted fuze down, the force of the main charge invariably drove the fuze into the shell, causing a failure to detonate or, worse, a premature detonation in the tube.

The excessive windage in early muzzle-loading cannon, however, allowed the fire from the main charge to ignite the fuze even when the shell was loaded with the fuze facing toward the muzzle. This was discovered, reportedly during the siege of Limerick in 1689, when an English mortar was fired accidently without the fuze having first been lit, and yet the shell exploded anyway. Shells were then fired from long guns by being secured to wooden bases, known as sabots, that automatically positioned the fuze toward the muzzle. Fuzes also evolved.

Shells underwent great change in the late 19th century with the development of breech-loading guns, steel projectiles, and new high-explosive fillers. In modern parlance, the term “shell” has come to mean any artillery round. Shells come in a wide variety of types including, but not limited to, high-explosive, high-explosive antitank, armor-piercing discarding sabot, incendiary, smoke, illumination, chemical, and nuclear (which were removed from the U.S. arsenal in the 1990s). Fuzes have also become much more sophisticated and reliable and include mechanical time, point-detonating, delay, and proximity types.

Further Reading

Hogg, Ivan V. A History of Artillery. New York: Hamlyn Publishing Group, 1974.

Hogg, Ivan V. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Ammunition. London: New Burlington, 1985.

Shrapnel (Spherical Case Shot)

The artillery projectile known as shrapnel or spherical case shot was invented in 1784 by Lieutenant (later lieutenant general) Henry Shrapnel (1761–1842) of the British Royal Artillery. Shrapnel came up with the idea in order to extend the range of highly effective case or canister shot against enemy troops.

During the Spanish siege of Gibraltar (1779–1783), the British successfully fired 5.5-inch mortar shells from their 24-pounder long guns, but in 1784 Shrapnel improved on this by inventing what he called “spherical case shot.” The new artillery ammunition was later known simply by its designer’s name. It consisted of a thin-walled hollow round shell filled with a small bursting charge and small iron or lead shot. A time fuze set off the charge in the air, scattering the shot and pieces of the shell casing among opposing troops. The bursting charge was only a small one, allowing the scattered balls and burst casing to continue on the same trajectory as before the explosion (a greater charge would increase the velocity but scattered the balls more widely and reduced their effectiveness). Explosive shell had for some time been utilized in high-trajectory fire mortars but had not before been widely projected in horizontal fire by guns.

Shrapnel shells had thinner walls than other shells and had to be carefully cast. Their weight empty was about half of that for solid shot of the same caliber, but their loaded weight was comparable to solid shot.

The British first fired shrapnel during the Napoleonic Wars in 1804 in the siege of Surinam and continued to use it thereafter. Early shrapnel had a wooden plug and a paper fuze but in the 1850s incorporated the more precise Bormann fuze. Shrapnel was widely used in the American Civil War both on land and in naval actions, most often in the 12-pounder Napoleon and Dahlgren boat howitzers. Shrapnel soon became a staple round in the world’s artillery establishments. Britain alone produced 72 million shrapnel shells during World War I.

By the end of the 19th century, shrapnel rounds had evolved to a similar size and shape as the other cylindro-conoidal shells fired by breech-loading artillery. The operating principle was still similar to the original spherical case. The thin-walled projectile was packed with small steel or lead balls and an expelling charge. The expelling charge, however, did not rupture the projectile. Rather, it blew the fuze off the front end and expelled the shrapnel balls forward. Thus, the shrapnel round was something like a huge flying shotgun shell. Because of the imprecise burning times of the black powder time fuzes of the era, the adjustment of the proper height of burst was very difficult. Also, shrapnel was only effective against troops in the open. As trench warfare set in during World War I and field fortifications became more robust, shrapnel became virtually worthless. Meanwhile, advances in both explosives and metallurgy during World War I finally produced high-explosive shells that had both significant blast and fragmentation effects. After World War I shrapnel completely disappeared, replaced entirely by high-explosive (HE). Today, the fragmentation produced by the detonation of an HE round is popularly but incorrectly called “shrapnel.”

Further Reading

Bull, Stephen. Encyclopedia of Military Technology and Innovation. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2004.

Ripley, Warren. Artillery and Ammunition of the Civil War. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1970.

Tucker, Spencer C. Arming the Fleet: U.S. Navy Ordnance in the Muzzle-Loading Era. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989.