Men’s conception of themselves and of each other has always depended on their notion of the earth.

—ARCHIBALD MACLEISH, “RIDERS ON EARTH TOGETHER, BROTHERS IN ETERNAL COLD”

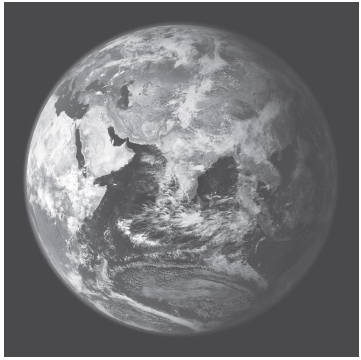

FIGURE 1.1. Blue Marble. Image by Reto Stöckli, rendered by Robert Simmon. Based on data from the MODIS Science Team

The spectacular images from the 1968 and 1972 Apollo missions to the moon,

Earthrise and

Blue Marble, are the most disseminated photographs in history.

1 Indeed,

Blue Marble, the most requested photograph from NASA, is the last photograph of the planet taken from outside Earth’s atmosphere.

2

Whereas Earthrise shows the earth rising over the moon, with elliptical fragments of each (the moon is in the foreground, a stark contrast from the blue and white earth in the background), the later image, Blue Marble, is the first photograph of the “whole” earth, round with intense blues and swirling white clouds so textured and rich that it conjures the three-dimensional sphere.

Even more than previous photographs of Earth, the high definition of

Blue Marble and the quality of the photograph make it spellbinding. Set against the pitch-black darkness of space that surrounds it, the earth takes up almost the entire frame. Unlike in

Earthrise, in

Blue Marble the earth does not look tiny or partial, but whole and grand. Both of these photos from Apollo missions (8 and 17) were immediately met by surprise, along with excited exclamations about the silent beauty of this “blue marble,” this “pale blue dot,” this “island earth.”

3FIGURE 1.2. Earthrise. Image Credit: NASA

In the frozen depths of the cold war, and over a decade after the Soviets launched the first satellite to orbit Earth, Sputnik, these images were framed by rhetoric about the “unity of mankind” floating together on a “lonely” planet. At the same time as vowing to win the space race with the Soviet Union, the United States wrapped the Apollo missions in transnational discourse of representing all of “mankind.” Indeed, these now iconic images ignited an array of seemingly contradictory reactions. Seeing Earth from space generated new discussions of the fragile planet, lonely and unique, in need of protection. These tendencies gave birth to the environmental movement. At the same time, the Apollo missions spawned movements to unite the planet through technology. Heralded as man’s greatest triumph, the moon missions lead to a flurry of speculation on not just the technological mastery of the world, or of the planet, but also of the universe. While seeing Earth from space caused some to wax poetic about Earth as our only home, it led others to imagine life off-world on other planets. While aimed at the moon, these missions brought the Earth into focus as never before.

The photographs of Earth from space sparked movements aimed at “conquering” our home planet just as we had now “conquered” space. Indeed, critics of these early ventures into space asked why we were concentrating so many resources on the moon when we had plenty of problems here on Earth, not the least of which was the threat of nuclear war (Time 1969). The Apollo missions were a direct outgrowth of this threat in terms not only of the significance of the race to space but also rocket technologies, which originated with military developments in World War II. The atom bombs dropped in Japan in 1945 heralded the nuclear age with the threat of total annihilation. And the development of rockets by both the United States and Germany as part of military strategies in WWII gave rise to rockets launched into space by the USSR and USA in decades that followed. Indeed, the U.S. recruited German scientists to work with NASA.

Within a decade, we had gone from world war and the threat of genocide of an entire people, to the possibility of nuclear war and the threat of annihilation of the entire human race. And, within another decade or two (with Sputnik and then the Lunar Orbiter and Apollo missions and photographs of Earth from space), the

world gave way to the

planetary and the

global. Following Heidegger, we might call this “the globalization of the world picture.”

4 Indeed, upon seeing the Earth from space, Astronaut Frank Borman exclaimed, “Oh my God! Look at that

picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, that is pretty! You got a colour film, Jim?” And William Anders responded, “Hand me that roll of colour quick.”

5 The Earth had become a

picture even before the photo was taken. Within a few short decades, the rocket science used by the military in WWII had given rise to the globalism that we have inherited today. From global telecommunications such as cell phones and Internet to global environmental movements, the Apollo missions moved us from thinking about a world at war to thinking about the unification of the entire globe. If, after seeing

Earthrise, as Archibald MacLeish claims, “Men’s conception of themselves and of each other has always depended on their notion of the earth,” then, in order to understand ourselves and our interactions with other earthlings we need to ponder the meaning of

earth and

globe and the place of human and nonhuman worlds in relation to them.

FROM GLOBALIZATION TO EARTH ETHICS

In this book, we explore some philosophical reflections on earth and world, particularly insofar as they relate to the globe, and thereby to globalization, to begin to develop an ethics of earth, or earth ethics. Starting with Immanuel Kant, we follow a path of thinking our relations to each other through our relation to the earth. We move from Kant’s politics based on the fact that we share the limited surface of the earth, through Hannah Arendt’s and Martin Heidegger’s warnings that by leaving the surface of the earth we endanger not only politics but also our very being as human beings, to Jacques Derrida’s last meditations on the singular world of each human being. This trajectory leads us from Kant’s universal laws, which apply to every human being equally because we share the surface of the earth, through Arendt’s insistence on a plurality of worlds constituted through relationships between people and cultures, and Heidegger’s thoroughly relational account of world and earth as native ground, to Derrida’s radical claim that each singular human being—perhaps each singular living being—constitutes not only a world but also the world. In all of these thinkers we find a resistance to world citizenship and to globalization, even as some of them embrace different forms of cosmopolitanism. And yet, in their work we also find the resources to think the earth against the global in the hope of returning ethics to the earth. The very meaning of earth and world hang in the balance. So too does our relationship to earth, world, and to other earthlings.

The guiding question that motivates this book is: How can we share the earth with those with whom we do not even share a world? The answer to this question is crucial in terms of figuring out whether there is any chance for cosmopolitan peace through, rather than against, both cultural diversity and the biodiversity of the planet. Can we imagine an ethics and politics of the earth that is not totalizing and homogenizing? Can we develop earth ethics and politics that embrace otherness and difference rather than co-opting them to take advantage of a global market? How can we avoid the dangers of globalization while continuing to value cosmopolitanism? Following the trajectory from Kant’s universalism to Derrida’s radical singularity, we explore different conceptions of earth and world in order to develop an ethics grounded on the earth. Inspired by Kant’s suggestion that political right is founded on the limited surface of the earth, and Derrida’s suggestion that each singular being is not only

a world but also

the world, we can articulate an ethics of sharing the earth even when we do not share a world. This earth ethics is based on our shared cohabitation of our earthly home. Building on insights from Kant, Arendt, Heidegger, and Derrida, we conclude with an ethics of earth that is formed through tensions between politics as the sphere of universals and ethics as the sphere of the singular, tensions between world and earth, or what Heidegger calls “strife” between the two. Our ambivalent place on earth is signaled in that tension. The tension between politics and ethics, world and earth, resonates with the contradictory reactions to the first images of earth from space, urges to master along with humility, urges to flee along with the urgent desire for home. Acknowledging our ambivalence toward earth and world may be the first step in accepting that, in spite of the fact that we cannot predict or control either of them, we are responsible for both.

What we learn from Kant is that public right demands a universal principle of hospitality based on the limited surface of the earth. Although Kant limits hospitality to the right of visitation, still the “original common possession” of the earth’s surface becomes the basis for all political rights. Taken to its logical limits, Kant’s suggestion that political right is grounded on the earth as common possession undermines private property. In addition, the clear limit that Kant delineates between politics and morals begins to blur. What happens, then, when we start with Kant’s insights into the connection between politics and the earth and extend them to ethics? Here, Kant’s remarks on hospitality become the basis for an ethics of the inhospitable hospitality of the earth. Derrida famously extends Kant’s hospitality to its limit in unconditional hospitality to the point that we can no longer defend individualism or nationalism—indeed, to the point where we can no longer distinguish between host and guest, hospitality and hostility.

6 Arendt too extends Kant’s notion of cosmopolitan hospitality to ground the always shifting “right to have rights,” which takes us beyond nationalism and toward our shared coexistence and cohabitation of both earth and world.

7 Although Kant is clear that cosmopolitanism is a public or political right and not a moral one, he also insists on harmony between morals and politics.

8 Contemporary criticisms of Enlightenment universalism, however, have reopened the split between morals and politics. Or, perhaps more to the point, both morals and politics are seen as at odds with ethics. If morality and political rights are necessarily universal, how can they account for singularity and the uniqueness of each individual? Derrida, among others, has tried to reformulate Kant’s principles of hospitality and cosmopolitanism in order to take into consideration the singularity of each person, even of each living being.

9 The question, then, is: Can we negotiate between moral universalism and ethical particularism? Following Kant, Arendt, and Derrida, we must grapple with this tension between universal and particular, which sometimes shows up as a tension between nationalism and cosmopolitanism.

In this vein, Arendt struggles with the tension between national rights and human rights. While she embraces the plurality and unpredictability of the human condition, she insists on the necessity and priority of state rights over generic human rights. She argues that the notion of

human rights reduces the human being to its species, like an animal, and does not have the force of any law behind it. Unlike rights guaranteed by sovereign states, human rights come with no such guarantee. While she allows for international laws that might provide such protection for stateless peoples, she also argues in favor of state citizenship and reminds us of the importance of membership in nation states, at least in a world where international law does not provide adequate protections for stateless peoples.

10 The Apollo missions with their America First rhetoric of winning the cold war along side their transnational rhetoric of goodwill to all mankind are emblematic of this tension between nationalism and cosmopolitanism.

What we learn from Arendt is that politics is not primarily a matter of law, nor of hospitality per se, but rather it is based on the plurality of our cohabitation of both earth and world, a plurality through which we can and must create equality in the face of nearly infinite diversity. Arendt’s distinction between earth and world provides important resources for rethinking Kant’s notions of public and private right, the tension between morals and politics, and the notions of common possession and private property, especially in relation to war. For Kant, war is the result of the fact that we share the limited surface of the earth, and yet this same fact can and should eventually lead to perpetual peace. For Arendt, the plurality and diversity of our coexistence on earth leads to war; yet for the sake of politics, and ultimately for the sake of the endurance of human worlds, war must be limited. Arendt imagines a plurality of worlds formed through human interaction and relationships. While in some sense these worlds are of our choosing, in another sense they are radically unchosen. We are born into a world, worlds, and the world. Moreover, as she tells Eichmann, none of us has the right to choose with whom to share the surface of the earth. The unchosen nature of our earthly cohabitation gives rise not only to political obligations but also to ethical ones.

And yet, as we learn from Heidegger, the givenness of our inheritance must be continually taken up as an issue for the sake of the future of each individual and each people. While it is true that we are born into a world that we do not choose and that the unchosen character of our earthly cohabitation brings with it plurality, diversity, unpredictability, and promise, in order to become properly thought it must be interpreted and reinterpreted. Going beyond Heidegger, we could say that the unchosen nature of our earthly habitation and cohabitation must be taken up in order to become properly political and ethical. In other words, the givenness of inhabitation and cohabitation is not enough in itself to ensure that we act ethically or extend political rights toward other earthlings or the earth. Going beyond merely sharing the earth’s limited surface or the plurality of cohabitation, Heidegger adds profound relationality that makes every inhabitant fundamentally constituted through its relation to its environment. This interrelationality is not just the result of earthly ecosystems that sustain the life of each individual and each species. Rather, for Heidegger, this interrelationality operates at the ontological level whereby the very being of each individual and each species comes into being through relationships and relationality. With Heidegger, we get a sense of what it means to cohabit the earth as a dynamic of buzzing, flowing, raging, blowing, thanking, thinking, dwelling, and warring. If for Kant and Arendt our relations to the earth and to the world ground political right and politics itself, for Heidegger our relations to earth and world are not only constitutive of our very being but also of the ethos in which we live, all of us together in strife and wonder, cohabitants of earth. Following Heidegger, we can begin to imagine sharing the earth, even if we do not share a world. But, moving beyond Heidegger, we can begin to articulate an ethics of earth based on this sharing and not sharing.

What we learn from Derrida’s last seminar is that we both do and do not share the world. Emphasizing the profound singularity of each being—not just human beings—Derrida claims that with each one’s death the world is destroyed. This radical claim evokes a sense of urgency in relation to ethics and politics. Reformulating the tension between ethics and politics supposedly resolved by Kant, Derrida embraces the impossible intersection of ethics and politics, of the demand to respond to the singularity of each and the demand for justice for all. Derrida takes us beyond Kant’s notion of universal conditional hospitality to singular unconditional hospitality in the face of the absence of the world, particularly the world of moral calculation. This incalculable obligation to others—even the ones whom we may not recognize—challenges all political pluralities and notions of “peoples” in whose names “we” act. Derrida’s analysis brings to the fore the tension between ethical obligations that take us beyond calculation or universal principles and political obligations that necessitate calculation and universal principles. Emphasizing the radical singularity of each living being, in his last seminar Derrida employs the figure of an island. The island connotes isolation, even loneliness, cut off from civilization. Each singular life is an island cut off from all others. But even Robinson Crusoe on his desert island is not alone. The desert or deserted island is an illusion, a fantasy of autonomy and self-sufficiency. The ethical obligation that stems from the singularity of each living being is not Robinson Crusoe’s solipsistic delusion of mastery or control over himself or the plants, animals, and, ultimately, other humans that both share and do not share that island. On the one hand, Derrida insists that we do not share the world and that each singular being is a world unto itself, not just

a world, but

the world. On the other hand, and at the same time, we are radically dependent on others for our sense of ourselves as autonomous and self-sufficient, illusions that come to us through worldly apparatuses. We both do and do not share the world. With Derrida we get a sense of ethical urgency that we must return from the world to the earth. Even when the world is gone, the earth remains. Even if we do not share a world, we do share the earth. Moving from Kant’s political right founded on the limited surface of the earth, through Arendt’s plurality of worlds, and Heidegger’s profoundly relational account of earth and world, to Derrida’s ethics that begins when the world is gone, these chapters return earth to world and thereby ground ethics on the earth.

This book brings the urgency and responsibility of ethical obligation together with a sense of home or habitat as belonging to a community conceived as ecosystem and ultimately as belonging to the earth. By emphasizing the radical relationality of each living being, together with our shared but singular bond to the earth, the island no longer appears deserted or isolated, but rather inhabited by immense biodiversity and surrounded by oceans teaming with life that we risk discounting at our peril.

11 Indeed, the island is the meeting of land and sea, an in-between space, which provokes uncanny ambivalence. When we disavow the uncanny strangeness and our own ambivalence toward it, we then risk reducing the island to the fantasy of barren isolation or exotic paradise, neither of which is sustainable. The danger of the island metaphor is that it becomes a figure for isolation rather than a figure for the in-between, the meeting of land and sea. Even Derrida’s invocation of the island as a figure for singularity risks overshadowing the necessary interconnections and interrelationality through which, and in which, habitation happens. The island metaphor when extended to the earth itself discounts the very features that make the earth unique, namely the dynamic relationships between land and sea, globe and atmosphere, planet and solar system. Moving from Kant to Derrida, can we begin to articulate an ethics and politics grounded on the earth, not as isolated island or totalizing globe, but rather as the unknown and unpredictable source of diverse life on our uncanny earthly home. Earth ethics is grounded on the earth as the home to cultural diversity and biodiversity and a plurality of worlds.

WORLD WAR, EARTH ANNIHILATION

Obviously, Kant never saw the Earth from space. But that didn’t stop him from imagining how it might look to alien space travelers. Kant’s appeals to extraterrestrials to make various points throughout his work are infamous.

12 And, his philosophy of public right is based on thinking of the earth as a whole. Hannah Arendt was fifty-one years old when Sputnik sent photographs back to Earth, and she died three years after Apollo 17 sent back the now famous

Blue Marble photograph. Martin Heidegger was sixty-eight when Sputnik circled the Earth, and he died one year after Arendt in 1976. News of Sputnik and photographs of Earth from space profoundly affected both Arendt and Heidegger. And both warned of the dangers of severing our connection to Earth in favor of interplanetary thinking. Jacques Derrida, who died in 2004, was only twenty-seven when Sputnik made its appearance. He gave his last seminars in Paris in 2002 just as the United States went after Al Qaeda in Afghanistan and waged war against Saddam Hussein for a second time, using the most technologically advanced military arsenal on the planet. One of Derrida’s last texts published before his death was

Philosophy in a Time of Terror, his response to the attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, in which he criticizes globalization for widening the gap between the rich and the poor while embracing the rhetoric of unification and equality (2003a).

While Kant could not have imagined the threats of nuclear apocalypse or global terrorism, he did argue that nation-states must not do anything in war to preclude future peace (Kant 1996c [1795]). Even while he maintained that through war human beings find political equilibrium and develop as peoples and nations, he also imagined the possibility of perpetual peace by limiting war. For Kant, war was necessary within limits. And the surface of the earth provides the absolute and ultimate limit to both individual and national expansion. In the face of the apparent limitless threat of nuclear war, however, the so-called superpowers looked to space to escape the limitations imposed by the surface of the earth. While imperialist expansion on our own planet was limited by war, the technologies of war and the race for military dominance of the world gave rise to the possibility of colonizing space. If in the eighteenth century Kant imagined the cosmopolitan unification of the world through the necessary evil of war, after the images of Earth from space, twentieth century thinkers hoped for the unification of the globe through the dystrophic fantasy of the annihilation of the entire planet. American imperialism took on tones of unifying all humankind through space exploration, even while promoting America first and dominance over the Russians and then the Chinese. On the one hand, the possibility of nuclear destruction lead us into space during the cold war and, on the other, the military technologies produced during World War II propelled us into space.

The real nuclear destruction in World War II and the threat of nuclear war during the cold war sparked fantasies of nuclear devastation in the popular imaginary. Films such as Roger Corman’s

The Day the World Ended (1956), Stanley Kramer’s

On the Beach (1959), Stanley Kubrick’s

Dr. Strangelove (1964), and the James Bond film

You Only Live Twice (1967), along with lesser known films such as

The Final War (1960) and

The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961), all revolved around the threat of nuclear destruction, many of them imagining what would happen if the USA or USSR “pushed the button.”

13 The mushroom cloud became the iconic image of nuclear destruction. After the Apollo photographs of “whole” earth, the mushroom cloud and fear of nuclear destruction was joined in our cultural imaginary by images of other types of annihilation of the entire planet through our own pollution and climate change or at the “hands” of aliens, themes that continue to be popular in Hollywood film today. Some in the environmental movement spurred on by the Apollo photographs imagined the Earth itself as our enemy, taking its revenge on us by trying to eradicate us from its surface (see Lazier 2011, 619). The mushroom cloud and the iconic Blue Marble became intertwined in popular investment in the fantasy of

whole earth.

14It was as if we could think the whole earth only by imaging its destruction, that all attempts to “save” the planet require first imagining destroying it. This same tendency shows up in contemporary philosophical attempts to think earth and world. For Kant, the limited surface of the earth leads to both war and peace. Arendt thinks both earth and world in relation to the nuclear threat and space-exploring technologies that threaten their destruction. As in Kant’s discussion of earth, war plays a central role in Arendt’s discussions of both earth and world. The genocide of World War II prompts her discussion of what it means to have a world and whether we occupy different worlds; furthermore, she considers what it means when war is aimed at obliterating an entire world, as in the world of the Jewish people. Just as Kant argued that all war must allow for peace, Arendt argues that all war must allow for the existence of a plurality of worlds. She concludes in her analysis of the Eichmann trial, no one has the right to choose with whom he or she inhabits the earth. Unlike world war as it was waged before Hiroshima, nuclear war threatens not just the world of a particular people but also the Earth itself: we have the technology to destroy the entire planet.

War surrounds Heidegger’s thought in a more menacing way inasmuch as he was not only deeply affected by World War II but also joined the Nazi party. War is also central to Heidegger’s thoughts on both earth and world. Taking up the Greek notion of

polemos, however, as he does so many times, Heidegger complicates and reconceptualizes war as the strife, or constitutive tension, between revealing and concealing that ensures that both earth and world exceed technological enframing and calculation. While Heidegger warns that the technological worldview threatens earth and world annihilation, he also deploys an alternative conception of war as

polemos that takes us beyond warring nation states toward a more primordial force of the earth itself. In his last seminar Derrida’s reflections on world also lead him to war, particularly since the U.S. invaded Iraq at the same time as the final meetings of the seminar. Even before that point, however, Derrida’s remarks revolve around a line from a poem by Paul Celan, “the world is gone, I must carry you,” that guide his meditations on world, finitude, and solitude, ethics, death, and loneliness—a phrase that evokes the annihilation of the whole world.

It is not just in popular culture, then, that we think of the world only by imagining its destruction. In order to take the world as a whole, we imagine it gone. In order to see the whole earth, we fantasize its obliteration. In this regard, fantasies of Whole Earth and One World are nostalgic in that they begin with imaginary scenarios of annihilation followed by the longing for wholeness. In this retroactive temporality we embrace the earth and the world by first imagining them gone and then reconstructing them whole. In the words of the tagline of the 2013 film Oblivion, in which aliens have rendered the earth a barren desert and convinced the few remaining inhabitants, whom they have cloned, that habitable earth was irradiated through our own nuclear war, “Earth is a memory worth fighting for.” Is it a stretch to say that before the world wars, we had no sense of the world as a whole? And is it just coincidence that the images of the “whole” earth appear only through the threat of nuclear annihilation of the entire planet? Are the mushroom cloud and Blue Marble two sides of the same coin, namely the technological mediation of our relationship to both warth and world? (cf. Lazier 2011, 619). Did the threat of nuclear destruction change the world into a globe? Finally, does imagining the earth as a whole necessarily mean imagining its demolition? If so, this is certainly an example of what Derrida calls the logic of autoimmunity, namely that what is supposed to save us, the image of the whole earth, at the same time signals its self-destruction. Or, as Heidegger might suggest, do these images of destruction also contain the “saving power”? The seeming wholeness of Whole Earth and One World seen in the photos from space is a phantasm created by the fallout of the fantasies of world being gone and earth being obliterated. Might the fear of the destruction of earth and world inspire us to attend to our ambivalent relationship to our home planet? In part, it was this fear that inspired men to reach for the stars, the fear that life as we know it on earth might disappear one day. On “the day the world ended” and “the day the earth caught fire,” these men wanted to be ready to abandon ship and make a new start someplace else in the universe. Yet what they discovered, with their first ventures off world rocketing to the moon, is that looking back and seeing the Earth was the most profound moment of their mission. Certainly, the most enduring legacy of the Apollo missions remains the images of Earth from space.

“ESCAPE FROM THE PLANET THAT WAS NO LONGER THE WORLD …”

Immediately after the

Earthrise photograph was transmitted back to Earth from Apollo 8 on Christmas day 1968, poet Archibald MacLeish’s wrote an article in the

New York Times entitled “Riders on Earth Together, Brothers in Eternal Cold” in which he claimed the significance of the moon mission as changing our very conception of earth: “The medieval notion of the earth put man at the center of everything. The nuclear notion of the earth put him nowhere—beyond the range of reason even—lost in absurdity and war…. To see the earth

as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats, is to see ourselves as riders on the earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold—brothers who know now they are truly brothers” (MacLeish 1968, my emphasis). MacLeish speculates that seeing the earth “as it truly is” will “remake our image of mankind” such that “man may at last become himself” (1968). Seeing the earth “whole” for the first time unites all of “mankind,” together on “that little, lonely, floating planet.” Realizing that we are all in this together on the precarious lovely earth alone in the “enormous empty night” of space is seen as a catalyst for our finally coming into our own as a species united as “brothers.” When MacLeish calls the astronauts “heroic voyagers who were also men,” however, we cannot hear the universal mankind, let alone humankind, but rather the masculine heroic space cowboys who have the power and vision to unite all men as “brothers” against the eternal cold of space.

15MacLeish’s assessment is consistent with NASA’s press releases after both Apollo missions, which included panhuman themes of uniting mankind and representing all of mankind in space outside of any national borders.

16 For example, then NASA chief Thomas Paine told

Look magazine that photographs of Earth from space “emphasize the unity of the Earth and the artificialities of political boundaries” (quoted in Poole 2008, 134). NASA presented the Apollo 8 mission as one of peace and goodwill to all mankind (cf. Cosgrove 1994, 282). And, in 1969

Time named Apollo 8 astronauts Borman, Lovell, and Anders Men of the Year. The accompanying article described a new world born from their mission, one in which the human race could come together with one unified peaceful purpose as a result of the “escape from the planet that was no longer the world” (

Time 1969). The world had expanded to include the universe, while the earth had shrunk into a tiny fragile ball.

Time describes the earth as a troubled place full of war and strife and space as the great hope to “escape the troubled planet.” Again, the astronauts are seen as heroic figures conquering space: “It seemed a cruel paradox of the times that man could conquer alien space but could not master his native planet” (1969). The goal is clearly to conquer; and the Apollo missions signal a great victory in escaping a warring planet and moving beyond what appear from space as the petty disagreements between peoples. In the words of astronaut Frank Borman, “when you’re finally up at the moon looking back at the Earth, all those differences and nationalistic traits are pretty well going to blend and you’re going to get a concept that this is really one world and why the hell can’t we learn to live together like decent people” (quoted in Poole 2008, 133–134). The irony is that Borman claims that he only accepted the mission because as a military officer he wanted to “win” the cold war (see Poole 2008, 17). The Time article concludes that man will not turn into “a passive contemplative being” because he knows how to challenge nature; and in reaching for the moon he now conquered not only the seas, the air, and natural obstacles, but also space and the moon, which brings with it the “hope and promise of his latest conquest” (Time 1969, 17). Like Borman, the American media seemed to think of the Apollo mission as a triumph for freedom and hope, paradoxically both for “all of mankind” and as an American victory in the cold war (cf. Poole 2008, 134). The Apollo missions, then, are emblematic of our ambivalent relationship to the earth and to other earthlings. The reactions to seeing the Earth from space make manifest tensions between nationalism and cosmopolitanism and between humanism, in the sense that we are the center of the universe, and posthumanism, in the sense that we are insignificant in the universe. In these reactions to seeing the Earth, there are contradictory urges to both love it and leave it.

“ONE WORLD” AND “WHOLE EARTH”

Ideals of One World and Whole Earth, born out of the Apollo missions, make manifest some of these tensions that signal our ambivalent relation to the earth. The

Earthrise and

Blue Marble photographs became emblems of both ideals. One World is the idea that technoscience can unite all of the nations of the world, while Whole Earth is the idea that concern for the shared environment can unite all peoples on the fragile planet Earth. Whereas for One World advocates the photographs of Earth from the Apollo missions signify “secular mastery of the world through spatial control,” for Whole Earth advocates they represent “a quasi-spiritual interconnectedness and the vulnerability of terrestrial life” and “the necessity of planetary stewardship” (Cosgrove 1994, 287).

17 Whereas One World is the image of the entire planet connected through technology, Whole Earth is the image of the entire planet interconnected organically through the uniqueness of Earth’s fragile biosphere.

The sentiments of Buckminster Fuller epitomize the One World view of the Earth as a technological wonder that unites mankind: “our space-vehicle Earth and its life-energy-giving Sun and tide-pumping Moon can provide ample sustenance and power for all humanity’s needs” (quoted in Lazier 2011, 284). While this utopian vision is far from realized on Spaceship Earth, the technological goal of uniting the planet through telecommunications is increasing its reach, if not across the entire globe then certainly across a sector of the earth determined by access to technology through wealth. Still, early telecommunications originated in military operations. The first satellites were cold war technologies developed to spy on the enemy. The One World reaction with its ideal of global technology comes out of the conquering model voiced by astronauts and media alike in response to the cold war. For, even more than most, the cold war was about technology and the race to the moon was a battle over the future of technoscientific progress. According to Time, if we could conquer alien space, then we should be able to master our native planet (Time 1969).

The Whole Earth reaction, on the other hand, with its notions of organic interconnectedness and the vulnerability of our native planet, comes from the “loneliness” of Earth seen floating in the “vast night” of space. Perhaps more surprising than One Worlders’ reveling in the technocratic triumph of the moon missions was the solemnity of realizing that Earth is the only body that looks even remotely alive from that vantage point. While it is not so surprising that astronauts may have felt alone floating in their space capsule thousands of miles from any other living soul, it is remarkable that their sense of isolation was contagious. Each one of them expressed the loneliness of space, from which Earth appears as an oasis. For example, on a later mission, Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins voiced the loneliness and vulnerability of Earth when circling the dark side of the moon alone in the Command Module: “I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life…. Then, as the Earth rose over the lunar horizon: so small I could blot it out of the universe simply by holding up my thumb…. It suddenly struck me that that tiny pea, pretty and blue, was the earth … I didn’t feel like a giant. I felt very, very small.”

18 Collins’s remarks express the contradictory reactions to seeing Earth from that distance. On the one hand, he imagines blotting out the Earth with his thumb and on the other he imagines himself as very small and insignificant. The power and mastery of technological prowess is counterbalanced by the vastness of the universe that makes our entire planet look like a “tiny pea.”

The first astronauts to circle the moon all expressed similar sentiments, emphasizing the loneliness, uniqueness, and fragility of Earth. Apollo 8 mission commander Frank Borman called Earth “a grand oasis in the big vastness of space.”

19 And astronaut James Lovell described the loneliness of space, “The vast loneliness up here is awe-inspiring, and it makes you realize just what you have back there on earth. The earth form here is a grand ovation to the big vastness of space.”

20 While Astronaut William Anders stressed the fragility of the tiny planet, referring to Earth as a “fragile Christmas-tree ball which we should handle with care.”

21 To these astronauts, and subsequently the media, along with One World and Whole Earth proponents, the Earth is alone in the universe, “a planet so eccentric, so exceptional” that the mission to the moon brought the Earth into focus (Lazier 2011, 623). Through the lens of the Apollo cameras, the lovely planet Earth appears as lonely as it is unique set against the absolute blackness of space. Seeing the Earth from space, so tiny, and yet the only visible color, prompted ambivalent feelings of vast loneliness and eerie insignificance along with immense awe and singular importance.

“THIS ISLAND EARTH”

Dreaming of islands … is dreaming of pulling away, of being already separate.

—GILLES DELEUZE, “DESERT ISLANDS”

Speaking of the Apollo 8 astronauts in a publication entitled

This Island Earth, NASA echoes the cosmopolitan sentiments of the unification of mankind, stressing that from the vantage point of space we see the “true reality” of our situation: “Their eyewitness accounts impressed millions of men with the true reality of our situations: the oneness of mankind on this

island Earth, as it

floats eternally in the silent sea of space.”

22 Resonant with the astronauts, along with writers like MacLeish, another NASA administrator hopes that “By heeding the lessons learned in the last decade, and attacking our man made problems with the same spirit, determination, and skill with which we have ventured into space, we can make ‘this

island earth’ a better planet on which to live.”

23 The comparison between the earth and an island works to highlight the supposed “reality” of our situation, all in the same boat, so to speak. Like an island, the Earth is imagined alone, floating in the infinite sea of space. And, like so many fantasy islands, some see it as paradise, while others can’t wait to escape from their exile here. Seeing Earth from space made some appreciate Earth anew, while others imagined moving further away from Earth and traveling to other planets. For some, seeing the loveliness of Earth “is to wish also to return” to it (Lazier 2011, 620); while for others, seeing the insignificance of Earth compared to the vastness of space is to wish to leave it. And, more to the point, the ambivalence between loving and leaving it shows up in various discourses around the first images of earth from space. In other words, these seemingly contradictory impulses, triggered within the cultural imaginary by the Apollo photographs, make manifest a deep ambivalence in our relationship to our earthly home. We feel both marooned and miraculous.

Indeed, in almost Heideggerian terms, mission chief Frank Borman recounts feeling nostalgic and homesick when he saw the “picture” of Earth from the moon: “It was the most beautiful, heart-catching sight of my life, one that sent a torrent of nostalgia, of sheer homesickness, surging through me.”

24 Certainly, the photographs of Earth from the moon continue to provoke the uncanniness of our relation to our home planet, particularly when we realize that we are “down there” somewhere, minuscule specks on that tiny “pale blue dot” floating in space. Carl Sagan’s recitation from the introduction to his

Pale Blue Dot sends shivers up the spine, as he reminds us that the tiny dot, barely visible from the vantage point of space, is our home and home to everyone who has ever lived. Just watch a YouTube video of Sagan’s presentation of

Pale Blue Dot to see what I mean. Sagan concludes, “There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known” (Sagan 1994, 7). Sagan’s book embraces the ambivalence of both love it and leave it, as the singularity of our home planet shines through the darkness of space and at the same time that vantage point reminds us of the adventurousness of the human spirit.

Even while encouraging us to love our home planet, Sagan would no doubt embrace Buzz Aldrin’s recent call to colonize Mars and become a “two-planet species.” “Our earth,” says Aldrin, “isn’t the only world for us anymore. It’s time to seek out new frontiers” (Aldrin 2013). While some, like Lovell, see the Earth from space and want to protect it, others, like Aldrin, imagine escaping from Earth to find our way in the galaxy, perhaps even in the universe. With environmental disaster looming large on the horizon, in recent years there is a sense among some that the Earth has betrayed us or is taking its revenge on us, and, rather than a safe haven, it has become a death trap and a threat to human survival (see Lazier 2011, 619). The urge to colonize Mars or find another habitable home is getting stronger, evidenced by the Mars One project, which plans to start colonizing Mars in 2023, less than a decade from now, and to continue bringing people on a one-way trip to Mars every two years from then on, for a permanent self-sustaining Mars settlement.

Although it is Robinson Crusoe’s island and not the earth that Derrida has in mind when he asks why some people love islands and are drawn to them while others fear islands and flee them, his analysis of the ambivalence conjured by islands is apt when considering contradictory reactions to seeing the earth from space. Indeed, on Derrida’s analysis the island becomes a figure for this ambivalence, for loving or leaving or, more accurately, both loving

and leaving. The figure of the island represents seemingly contradictory desires, namely to love and to leave, to cling to and escape from, to stand your ground and to flee. In this regard, the figure of the island might be what Julia Kristeva would call

abject in the sense that it cannot be categorized.

25 Rather it is always in between, between land and sea, between safe harbor and threatening isolation. Like everything abject, islands both fascinate and terrify. They fuel our ambivalent and contradictory desires to love and leave, to stay and to flee.

Derrida describes these ambivalent desires in Robinson Crusoe’s relationship to his desert island. The imagined circularity of Robinson’s island comes to represent a turn inward as a return to self. Even as Robinson longs to escape his family and England, he recreates their laws and customs on his island. In this sense, both literally and metaphorically, he recreates the wheel. Like Robinson’s wheel and his island, the earth spinning on its axis incites ambivalence. These contradictory reactions exist within one and the same nation, within one and the same person. And yet this ambivalence now figured by the island—this island earth—undermines the sovereignty of that nation and that person. In Derrida’s terms they contain within them the logic of autoimmunity that makes all

autos, all returns to self, eventually turn against themselves, and then what was intended to protect the self begins to destroy it. This mythical return to self contains within it a threat to self, the threat of self-annihilation. For example, technologies developed to provide endless energy deliver nuclear destruction. Or fossil fuel–driven technologies that allowed us to leave earth’s atmosphere and visit the moon contribute to the destruction of earth’s atmosphere and perhaps eventually the destruction of life on earth.

THE VIEW FROM SPACE

Certainly, in the case of contradictory reactions to the

Earthrise and

Blue Marble photographs, this ambivalent logic is operative as we acknowledge the singularity of our earthly home, and at the same time attempt to escape from it to find another home. Moreover, this autoimmune logic is intrinsic to the photographs themselves. For, in order to shoot those images, astronauts were propelled into inhospitable space in an unsustainable and precarious artificial environment where their very survival was uncertain. In other words, those images could only be taken from a vantage point where the survival of man is impossible. This extraterrestrial vista is from an impossible viewpoint where no one could live. In this way the photographs signal the danger inherent in the viewpoints of the people taking them. On the one hand, these two photographs, taken by human beings rather than unmanned satellites, have more rhetorical force because they are tokens of a human eyewitness standpoint. On the other, they also signal the perilous position of these space travelers who risk their lives while taking them. The only way to get what even NASA officials called this “God’s eye view” was from an impossible point so far away from Earth.

26 The view of the “whole” Earth could not be seen from Earth, but only at a distance born out of rocket science and compared to the viewpoint of God. As creatures on the earth, we cannot see the Earth; it is never a whole or total object presented to our perception. Apart from photographs, the view of the Earth as a whole has been reserved for the rare astronaut who left the Earth’s atmosphere. Speaking of their view of “the whole globe,” as “the first humans to see the world in its majestic totality,” astronaut Frank Borman exclaimed, “This must be what God sees,” and many of the astronauts talked of traveling to “the heavens.”

27 To see the Earth whole, as it “really is,” human beings must travel to the heavens to get a God’s eye view of the planet. Some earthlings even asked the astronauts whether they had seen God in space (Poole 2008, 129). The view of the whole Earth is the view of God. It is no wonder, then, that the Apollo missions sparked as much discussion of conquering and mastery as they did vulnerability and fragility.

What the astronauts, the media, and the One World and Whole Earth proponents assumed they saw in the photographs, particularly

Blue Marble, namely the whole Earth, however, was an illusion. For both images show only part of Earth, indeed, a fraction of the Earth.

Earthrise shows an elongated piece of the top of a sphere, while

Blue Marble shows one side of the Earth; and both are rendered in the two-dimensional space of the photographic medium. In other words, we

did not see what we thought that we saw. The impact of seeing the Earth whole, seeing it as it

really is, was based on the fantasy of the Whole Earth, which not only was never visible in these photographs but also, at least with current technology, never will be. The Whole Earth cannot be captured from any human vantage point, even one floating in a space capsule orbiting the moon or any other point in space. For, as phenomenologists teach us, the human perspective is always only partial; there is always something that is occluded and missing from our viewpoint.

28DOES THE EARTH MOVE?

Decades before the first Apollo mission, Edmund Husserl wrote an essay that he placed in an envelop with the title “Overthrow of the Copernican theory in usual interpretation of a worldview. The original ark, earth, does not move” written on the outside.

29 There, Husserl maintains that in our everyday experience, the earth does not move but is rather that in relation to which everything else moves. Speaking phenomenologically, we do not directly experience the spinning of the earth on its axis as movement. Husserl begins with the observation that, for us, “the earth is a globe-shaped body, certainly not perceivable in its wholeness all at once and by one person; rather it is perceived in a primordial synthesis as a unity of mutually connected single experiences” (Husserl 1981a, 222–223). Husserl goes on to argue that in order to have a notion of absolute motion and rest, we must take the earth as the basis-body (which is indeed no body, no thing, at all) as our ground, or what he calls

the earth-basis and

earth-basis arc: “Although for us it is the experiential basis for all bodies in the experiential genesis of our idea of the world. This ‘basis’ is not experienced at first as body but becomes a basis-body at higher levels of constitution of the world by virtue of experience” (Husserl 1981a, 222–223). In our everyday experience we do not perceive the earth as a body or a thing, but rather as the ground for our perception of all other bodies or things.

Husserl argues that even if we leave the earth and travel in space, perhaps even colonize other planets, the earth is still the basis of our experience insofar as we are born here and everything we know and experience is relative to life on earth. He says, “All of that is relative to the earth-basis ark and ‘earthly globe’ and to us, earthly human beings, and Objectivity is related to the All of humanity” (1981a, 228). He rejects the idea that human life could have sprung up on Venus or the Moon, suggesting that if there is life there it won’t be human life as we know it. We are essentially earthly creatures whose history and experience is inherently linked to the earth. The earth as the basis of that history and experience is not just one body among others, a planet like any other. Rather, it is our home. One of Husserl’s main arguments is that science should not forget that the earth is pregiven for us, and therefore all our understanding, knowledge, and theories are born out of that pregivenness. Or, as he puts it, “All brutes, all living beings, all beings whatever, only have being-sense by virtue of my constitutive genesis and this has ‘earthly’ precedence…. There is only one humanity and one earth” (1981a, 230). The earth is the primordial ark that makes everything else possible for us.

30 The function of the earth for Husserl is to bear and support us not only as our original home but also as the original body against, and through, which we experience our own bodies and the world. While it is true that in one sense the photographs of earth from space show us one body among others, this misses the point that we comprehend all other bodies in space only in relation to our earthly experience. We understand all other bodies in relation to the earth as our primordial ground, our basis-body.

Furthermore, the photographs of earth only show one portion of earth, one viewpoint on earth, and never the whole earth. This is because there is no possible human viewpoint from which to see the whole earth. That vantage point is impossible for us. Thus, if by “God’s eye view” we mean seeing the whole, then we can never adopt the position of God. Moreover, whatever we see has its origins in our earthly existence and is relative to the earth as the basis of our perception. Thus we can never see the earth “as it truly is” unless what we mean by “as it truly is” is what it is for us. Even then, post-Husserlian phenomenology has challenged the notion that there is universal meaning for all human beings. If we can only ever take a perspective on something, then it is possible that we may have different perspectives. Insofar as the earth is not a something like any other thing, but rather the ground for our perception of every thing as a something, then the problem of perspective becomes even more complex. If the earth is the basis for any and all of our perspectives, and even for our ability to take perspectives, then it is pregiven in a way that, as Heidegger says, is always concealed from us. Additionally, the pregivenness of the earth may be different for different peoples or cultures, which Heidegger suggests is linked to traditions and ultimately the earth as the “native ground” for “a people.” This is not to say that native ground or a people are homogeneous or universal either. For, as Derrida drives home, the phenomenological insight contains within it the autoimmune logic such that if we have perspectives all the way down, so to speak, then the constitutive genesis of the ego as transcendental, or universal, along with its native ground, begins to tremble. Our world, if not the very earth itself, begins to quake.

Both One World and Whole Earth impulses were based on the illusion that from space we could get a God’s eye view on the Earth as a whole. In this regard, in spite of their differences, they share the assumption that the photos show the totality of Earth as it “truly is.” The two are totalizing and global ideologies that promote managing the earth or mastering it, for the sake of global technology in the case of One World and for the sake of the global environment in the case of Whole Earth. Geographer Denis Cosgrove argues that both these totalizing movements depended on seeing the Earth whole, or more to the point, imagining seeing the Earth whole: “

Seeing the Earth whole is critical to the imaginative reception of the space images and to the totalizing socio-environmental discourses of One-world and Whole-earth to which they have become so closely attached” (Cosgrove 1994, 271).

But, we have not seen the Earth whole. And we have not seen the Earth as it truly is, isolated from everything around it. Indeed, without its atmosphere, the Earth would not look like the beautiful blue marble of the photographs. Furthermore, the Earth looks beautiful and unique relative to the black space around it, the gray surface of the moon, and the reflection of light from the sun. This is to say, the photographs are not just images of the Earth alone, but also the Earth in relation to the elements that surround it and constitute the Earth as more than just a planetary body. To take the Earth as an object apart from its relationships is the ultimate illusion of the mastery of our own subjectivity, a subject so powerful and grand that it can take the whole Earth as it object. As Heidegger might remind us, the Earth, even as seen from space, only appears in relationship to other elements, whatever those elements may be. In Heidegger’s terms, those elements include the sky (perhaps atmosphere), mortals (the finite limited human perspective of the astronaut’s holding the cameras), and divinities (perhaps what even the astronauts refer to as the heavens). To see Earth as an object floating alone in nothingness is to interpret the photographs within the technological framework that renders everything, even Earth itself, as an object for us, an object that can be grasp, managed, and controlled, an object ripped from its contextual home.

We haven’t seen the Earth whole and (unless something drastically changes in the constitution of human perception) we never will. As phenomenology teaches us, we never see any object in its entirely; rather, ours is always and only a perspectival seeing. If I cannot see what is closest to me, my own body, whole, then how can I expect to see the entire planet Earth whole? If we think that perhaps proximity is precisely the problem and, in order to see the whole, we need to get more distance and, like the astronauts floating in space, move further away from our object, we should think again. For, while changing proximity for distance can give us a different perspective, which may be enlightening, it does not give us a view of the whole. Whether we are looking at a table and chairs a few feet away or the Earth from space, we see only one side, one perspective, and cannot, and never will, see the whole in its entirety, as it truly is.

Thus we must question our investments in the whole earth fantasy. The wholeness supposedly seen in the first photographs of Earth from space is reminiscent of what psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan calls the

misrecognition of wholeness in the mirror stage.

31 Lacan describes the infant recognizing himself in the mirror for the first time and the ensuing fantasy of wholeness through which it compensates for the fragmentation of its experience. The image in the mirror presents a stable picture that the infant latches onto in order to prop up a sense of itself as autonomous and whole. And yet this is just a fantasy inasmuch as the infant’s experience is far from being either autonomous or whole. Indeed, as Lacan describes the scene, the infant is held there by its mother, or another caregiver, because it is still too young to stand in front of the mirror on its own. The mirror stage becomes emblematic of this imaginary process through which we attempt, never successfully, to compensate for our own fragmentation and lack of wholeness. The fantasy or misrecognition of wholeness provided by our imaginary projection onto the image in the mirror operates as a defense against the fact that our experience is always fragmented. We are never completely autonomous or whole, which causes anxiety, which in turn, we ward off with fantasies of wholeness. Visual images are the perfect medium to allow for this sense of stability, especially photographs insofar as they are frozen in time and space. And, perhaps more than any other medium, photographs present us with the illusion of stable presence outside the vagaries of time and space.

32Psychoanalysis might interpret the fantasy of wholeness upon seeing the photographs of earth from space as a defensive reaction against the sense of fragmentation that we actually experience.

33 Given the turbulence of the late 1960s and early 1970s in the U.S., the Apollo photographs, along with the fantasies of the “unity of mankind,” One World, and Whole Earth that they fuel, act to quell anxieties about the possibility of nuclear war and civil unrest. On the other hand, the environmental movement, hatched in the wake of these photographs, signals an investment in saving the earth from the devastation caused by humans. Certainly, many are invested in “saving the planet” by correcting or compensating for environmental damage humans have caused that may destroy our atmosphere, dramatically change our climate, and perhaps even render the earth uninhabitable for us. The fantasy of the whole earth allows us to continue with illusions of mastery and globalism, but now in the service of saving, rather than destroying, the planet.

Still, the notion that we can control and master our environment and our globe are part and parcel of the technological worldview that got us into an environmental mess in the first place. The mastering gaze that imagines itself taking the whole Earth as its object, through the Apollo photographs, perpetuates and emboldens a notion of human subjectivity as standing apart from its objects—in this case the earth—and over against them as the subjects controlling the destiny of those objects. Imagining the Earth as a body amongst others, as an object of our perception like others, is to imagine seizing it, controlling, and making it our own. But, as the most rudimentary foray into phenomenology reveals, we never see the whole of any object, but rather arrive at our sense of wholeness through processes of induction and deduction that are in themselves born out of our embodied experience as earthlings.

In the context of the cold war, and in the face of the threat of nuclear and environmental disaster, the photographs of Earth from space fuel a defensive reaction against such dangers through this fantasy of wholeness. Perhaps this is why

Blue Marble is the most reproduced photograph in history, and why the image of the whole Earth has become the symbol for globalization.

34 The danger of globalism and planetary thinking, as Kant, Arendt, Heidegger, and others point out, is the homogenization of the world into a globe and, more perilous, into a “world picture.”

35 A globe connotes something that we can control and manage, like the manufactured globes that we can hold in our hands, globes that we produce and possess. The photographs of earth from space turn earth into a globe that we imagine we can control and possess. Global thinking emerges after these first images of Earth from space. And with it comes totalizing discourses of uniting the entire planet through technology or through environmental management. Subsequently, global economy and global markets attempt to unite all humankind through consumerism, which not only incorporates and assimilates differences but also makes everything fungible. Everything has a price tag. Even saving Earth is reduced to offsetting one’s “carbon footprint” by paying for it. This totalizing sense of globalization shrinks earth’s cultural diversity and biodiversity as global technologies and economies expand. As Heidegger warned, the technological imperialism of the planet turns the earth into a globe, and we no longer dwell on our earthly home. Rather, globalism threatens the

desertification of both earth and world. The totalizing of this global technological worldview operates as if it had no limits and without remainder. And this is the danger, that the plurality of the earth and of the world(s) will be reduced, assimilated, and ultimately annihilated.

THE DANGERS OF GLOBALIZATION

Hannah Arendt criticizes privileging this view of earth from space, the “Archimedean” vantage point from which we can supposedly see our world and ourselves as they truly are. She argues that the Archimedean point in space will necessarily keep shifting, ever more distant from earth, as part of the fantasy that if we get enough distance on our home planet then we will see it as it really is and then we will be able to unlock its secrets. Once we find a point from which to view the earth, we will need to move onto another one from which to view that point and the whole, ad infinitum until the “only true Archimedean point would be the absolute void behind the universe” (Arendt 1954, 278). Arendt is critical of “our modern longing to escape what some call our imprisonment on earth” (Arendt 1958a, 1). From the distance of space, human activities, she warns, will not be recognizable as such; rather, we will look like rats, and our cars will look like snail shells or turtle shells attached to our backs (Arendt 1958a, 323, 1954, 278). On her view, if our behavior is compared to that of other animals’ behavior then we have been degraded. Of course, this assumes a problematic hierarchy of species.

Arendt contends that we are earthbound creatures who mistakenly see ourselves as dwellers of the universe (Arendt 1958a, 3). We imagine that we could live in that Archimedean point, off world, apart from earth. We labor under the illusion that because a few astronauts visited space we can live there. We believe that we can occupy the position from which to get “God’s eye” on our home planet. Arendt suggests that this race to escape the earth is an attempt to escape the human condition, which she claims is essentially terrestrial. Echoing Husserl, she maintains that our thinking is earthbound no matter where we are in space: “the human brain which supposedly does our thinking is as terrestrial, earthbound, as any other part of the human body. It was precisely by abstracting from these terrestrial conditions, by appealing to a power of imagination and abstraction that would, as it were, lift the human mind out of the gravitational field of the earth and look down upon it from some point in the universe, that modern science reached its most glorious and, at the same time, most baffling achievements” (Arendt 1954, 271). Her choice of the word

baffling is interesting in that it means both

bewildering and

deceptive, even connoting

cheating. To call the greatest achievements of science, particularly in terms of the “conquest of space,” baffling, is to suggest not only that they are bewildering or confusing but also that they are deceptive or frustrating. Perhaps even more baffling for Arendt is that the general reaction to these achievements is not bafflement, but rather matter-of-fact acceptance. The “step back,” as Heidegger calls it, that allows us to pause and think about ourselves and about our relation to earth and space requires a certain bafflement or bewilderment in the face of technological advances. Without it, we risk becoming complacent with a technological worldview that is so compellingly deceptive it tricks us into thinking that we have arrived at the objective perspective—what Arendt calls Einstein’s “free floating observer in space”—that Archimedean point, from which we see the earth and the world as “it truly is.”

Arendt is deeply critical of what she sees as an the impulse to create an artificial world to replace the natural one, in large part because she views it as an attempt to master the earth and the world by claiming the power to create even a second moon, and perhaps even a second earth and a second world. Resonant with Heidegger’s criticisms of technology, Arendt claims that the desire to escape the earth and create a new one someplace else is not only the result of denying the human condition at our own peril but also evidence of a dangerous hubris. The illusion that we can master the earth, our world, and space, leads to unchecked development and deployment of dangerous technologies that threaten all life on earth. Arendt sees this hubris in fantasies of space colonization and creation self-sustaining atmospheres for us elsewhere. Commenting on Sputnik, Arendt wrote to her mentor Karl Jaspers: “Most honored friend—What do you think of our two new moons? And what would the moon likely think? If I were the moon, I would take offense.”

36 And the very first words of

The Human Condition refer to Sputnik as the most important, and the most dangerous, event in human history.

We might wonder what Arendt would make of Biosphere 2, the self-enclosed artificial environment set in the Arizona desert where in 1991 eight people were locked in to see if they could survive for two years independently (they couldn’t), or current projects like the Netherlands based Mars One, which plans to colonize Mars by 2023 with funding from a global reality TV show documenting the astronaut selection process, for astronauts willing to make the one-way journey to the red planet. Will the Mars One project fulfill Buzz Aldrin’s dream of making human beings a two-planet species? Or, like Biosphere 2, will it show that human beings have only one habitable home, Biosphere 1, the Earth? Whatever happens, Husserl and Arendt would presumably share the belief that, at least until human beings are born and raised on Mars, they will still be earthlings, measuring everything according to Earth standards and using their terrestrial brains and bodies to understand their Martian environment. Furthermore, they will still have originated on Earth, which gave them life and sustained them so that they could explore space. And if they can make a life on Mars, and even if they find other life on Mars, insofar as they have a history and a past, a given from which they cannot escape, they will still be

of earth.

Given that for Arendt Sputnik shares the same desire to control the natural world as totalitarianism, it is likely that she would be appalled at both Biosphere 2 and Mars One.

37 Perhaps even more threatening than the replacement of natural with artificial, Arendt warns against the globalism inherent in both Sputnik and totalitarianism. Both, she suggests, manifest a desire to take over the entire globe, the same desire evident in the One World and Whole Earth movements. Arendt is more than skeptical about such movements, which claim to unite the entire world or the whole earth. Although Arendt thinks that international law is necessary to protect against genocide, she rejects appeals to abstract human rights or any type of world government (see Arendt 1992, 273). She argues that the rights of man, or human rights, are too abstract to protect individuals; rather than protect them, rendering persons

merely human reduces them to their species, which does not guarantee political rights (Arendt 1966, 300). For Arendt, each individual needs the protections of state citizenship, even if international law is also needed to protect entire states from each other.

Kant too warns against one world government, even as he argues for perpetual peace as a result of cosmopolitanism. This is why he proposes a federation of states that would maintain their own governments and also be governed by international law. For both Arendt and Kant, totalitarianism is a danger of globalism. In various ways both argue that we need the checks and balances of the possibility of war to make sure that any one state does not take over the world. Heidegger’s forceful delineation of the dangers of technological globalism is well known. On his account, globalism is inherent in the technological way of framing the world with its desire for world domination. Even Derrida, who extends Kant’s conditional hospitality to unconditional hospitality, rejects globalism.

38 He rejects even the words

globalism and

globalization. Like his predecessors, Derrida warns of the totalizing nature of globalism, which seeks control of the whole world without remainder.

This tendency reaches a certain zenith with terrorism insofar as terrorism is not tied to nation-states or citizenship, but is rather global. Terrorism is global in the sense of being able to strike almost anywhere and in the sense of threatening to destroy the entire world. In one of his last published works before his death, Derrida argues that now, with seemingly global access to technologies of destruction, the nuclear threat can come from anywhere. Unlike state violence, the terrorist threatens to strike almost anywhere at any time and threatens “the very possibility of world order.” Derrida claims that what is at stake is nothing less than the world itself, the worldwide or global insofar as all of life and the very planet are at risk.

39 The globalization of technologies of destruction threatens the entire world, without remainder. Just as Arendt worries about the totalitarian tendencies of globalism, and Heidegger warns of the totalizing discourse of technology as globalism, Derrida suggests that terrorism is an outgrowth of the logic of autoimmunity operating within technoscience that makes the destruction of the whole world possible. But now, in addition to the threat of nuclear war between nation-states, we have the threat of a terrorist atomic bomb or nuclear attack that, thanks to the proliferation of technology, could strike at any time and in almost any place on earth.

Technoscience has changed our relationship to both Earth and World. Now, thanks to technology, we not only can see the planet from space, but also can destroy it. Technology changes the relationship between the earth and the world. Once man ventured into space, the earth was no longer the world. Now that man has the power to destroy the earth, the illusion that man is the master of both earth and world threatens the destruction of both. Certainly, how we conceive of the earth is intimately linked to how we conceive of ourselves. If we see the earth as an object or a resource for our use, then we see ourselves as subjects and masters. If we see the earth as a pawn in a war or terrorism, then we see ourselves as sovereigns, even gods. But, if we see the earth as our singular home, then we see ourselves as earthlings who are profoundly dependent upon the earth. Moreover, we realize that we share the earth with all other earthlings such that we are not their masters, nor the master of earth. Rather than think our world limitless, and revel in the expansion of our powers, we understand that we are limited creatures and that our world(s) are fundamentally limited by their necessary relation to earth. As Heidegger cautions, technology changes the relationship between earth and world such that world threatens to overshadow and assimilate all of earth. This fantasy inherent in the technological worldview, the fantasy of wholeness and totalization, threatens not only our ways of life but also all of life on earth.

Derrida too warns that technology has changed meaning of earth as terra: “The relationship between earth, terra, territory, and terror has changed, and it is necessary to know that this is because of knowledge, that is, because of technoscience. It is technoscience that blurs the distinction between war and terrorism” (Derrida 2003a, 101). Technology equalizes access to weapons of mass destruction. And yet, even as technology seems to give equal access to all, it simultaneously increases inequities between peoples and nations. This is why Derrida rejects the term

globalization, because it implies that the entire globe has access to communication technologies or military technologies or so-called global markets (2003a, 121). But, this is far from true. As Derrida points out, “From this point of view, globalization is not taking place. It is a simulacrum, a rhetorical artifice or weapon that dissimulates a growing imbalance, a new opacity, a garrulous and hypermediatized noncommunication, a tremendous accumulation of wealth, means of production, technologies, and sophisticated military weapons, and the appropriation of all these powers by a small number of states or international corporations” (2003a, 123). At the same time that globalization appears to be equalizing access to global technologies or global markets, it is also increasing the divide between “haves” and “have nots.” For example, just a few countries control over 80 percent of the wealth, which is up considerably in the last few decades.

40 And, as a result of globalized markets, the top three billionaires in the world have more assets than the combined GNPs of all the least developed countries and their six hundred million inhabitants—three people have more than six hundred million people (Steger 2003, 105). The notion that globalization is good for everyone is a myth.

Resonant with Heidegger, Derrida also insists that worldwide markets or technologies are not global insofar as

the world is not synonymous with

the globe. In order to maintain the distinction between

world and

globe, Derrida says, “I am keeping the French word ‘

mondialisation’ in preference to ‘globalization’ so as to maintain a reference to the world

monde, Welt, mundus, which is neither the globe nor the cosmos” (2002a, 25).

41 While

globe refers to the entire planet,

world more narrowly connotes the world of human beings, or perhaps the worlds of particular species of beings, and maybe even the unique world of each singular living being. Indeed,

world allows for multiple worlds constituted by cultural and historical differences (among others), whereas

globe suggests the entire planet in its universal context, that is to say in the context of the universe. Although Derrida does not object to

globe or

global, as Heidegger does, because planetary thinking is at odds with the earth, he is clear that he thinks that

worldwide is more accurate than

global. Just as we interpreted the photographs of Earth from space as pictures of the whole earth, what we call

global or

globalization are merely fantasies of planetary wholeness. And, as Heidegger argues, the fantasy of planetary totality is dangerous when it positions itself as the only way to relate to the world.

42 The danger of this totalizing discourse is that it does not allow for differences, or even history, but rather insists on dominating everything that is.

Earth and World is an attempt to offset what Heidegger calls the

planetary imperialism of global technology and the totalizing technological worldview with earth ethics based on the singular bond to the earth that we share with all earthlings. Earth ethics operates as an antidote to both Heidegger’s nightmare of planetary imperialism, on the one hand, and Derrida’s fantasy of disconnected islands, on the other.

DESERT ISLAND

An island doesn’t stop being deserted simply because it is inhabited.

—GILLES DELEUZE, “DESERT ISLANDS”

It is noteworthy that within the metaphorics of the philosophical trajectory of these thinkers, the technological impulse to cover the entire planet reduces the world to a

desert. While Kant merely mentions the desert as an inhospitable region across which, thanks to the fortunes of providence, camels can transport us as the “ships” of the desert, the figure of the desert becomes a metaphor for the inhospitable regions of political geography for Arendt. Arendt describes the