11

THE BUDDHA was a being of outstanding brilliance.And all things that emanate such radiance inevitably seem to cast a shadow somewhere. One might then ask the question, Where did the Shadow exist in the Buddha’s life? Although the term Shadow is not used in Buddhism, the principle is far from absent. In the life of the Buddha there are two figures, one symbolic and the other supposedly actual and historical, that play a curious role. One of these is known as Mara, and the other is a relative of the Buddha named Devadatta. Their role in the unfolding of the Buddha’s journey seems to be that of a hindrance, adversary, or enemy, or perhaps, psychologically, the Shadow.

It is said that when the Buddha was seated beneath the Bodhi tree in Bodhgaya, India, during the last phase of his path towards enlightenment, Mara devised tests and temptations intended to distract him from his meditation. Mara plays a role similar to that of the devil in the temptation of Christ in the desert. However, unlike the devil, he is not seen as such a literal entity. Mara was the name given in the Buddhist world to the obstacles and hindrances that arise in our path to make us deviate from awakening. He, although gender is not specific, is given a demonic personification, as though he is a symbolic aspect of our inner saboteur that emerges when we are intent on the journey. Mara manifested to the Buddha as beautiful women, as fierce attacking soldiers, and as terrifying monsters, each intended to find a chink in the Buddha’s impeccability. If there had been a hook for these phantoms to use to gain a hold, the Buddha would have failed in his intention. His impeccability was such that they could not shake his meditative equipoise and therefore became powerless. The beautiful sirens became old hags and the weapons became a rain of flowers.

Devadatta has a different origin, yet he too is vilified as the antithesis of the Buddha’s purity, goodness, and perfection. He is said to have been born close to the Buddha in each of his incarnations. He is usually a relative; in the Buddha’s incarnation as Siddhartha, Devadatta was his cousin. It is said that on various occasions Devadatta, who was jealous of the Buddha and all that he represented, attempted to kill him. Usually the Buddha employed some miraculous insight to foresee what would happen and avert the danger.

It is apparent that on a symbolic level both Mara and Devadatta embody a shadowy aspect of the Buddha’s apparently impeccable life. One could see this rather simplistically as the struggle between the forces of good and evil. It is perhaps a little more complex.

In the case of both the Buddha and Christ, one could argue that without these shadowy characters, they would not have achieved what they did. Is Mara an inevitable or even necessary aspect of our path that manifests to enable us to grow? It is apparent from Buddhist teachings that Mara represents primarily an internal delusional force that must be faced in the process of awakening. The capacity to resist the pull or beguiling presence of this aspect of ourselves is a natural aspect of transformation. The position of Devadatta is less clear.

I have often wondered what was supposed to have happened to Devadatta, since even to contemplate a harmful thought towards the Buddha was said to result in rebirth in the deepest hell. Whenever I have asked Tibetan lamas whether Devadatta would be able to overcome this negative disposition and attain enlightenment, they have almost invariably laughed somewhat awkwardly and given no answer. It is as though he represents an enigma that seems to be overlooked or ignored.

My reason for wanting an answer to this question was primarily because I was conscious that almost all the tales of holy beings put forward as exemplary practitioners were of those who were already extraordinary at the time of their birth. In the Gelugpa tradition, for example, the life of Tsongkhapa, its founder, is venerated as that of the perfect practitioner. He was, however, already considered an incarnation of the Buddha Manjushri at birth. I wanted to know what the path was like for someone who was less exalted; for someone with shadowy faults and problems, who would struggle with heretical views and deeply entrenched negative habits.

I think one reason I found my retreat teacher Gen Jhampa Wangdu so inspiring was that he was a very ordinary person who, as a young man, had truly struggled with the monastic establishment he was part of. According to stories I have been told by one of his closest friends, he had been something of a roughneck who was quite mischievous as a young monk. When I met him and he began to teach me, I was inspired not just by the depth of his insight and the power of his presence, but also by his ordinariness. He had attained profound realization as a man, not as some sort of saintly avatar who had graced us with a perfect incarnation.

Essentially I wished to learn how to deal with the shadowy side of my nature and found this easier to learn from someone who had clearly had to work with it. How do we transform the unruly, wild, emotional side of our nature that we struggle with to be “spiritual?” How do we heal the wounded side of ourselves that we are barely able, or often unwilling, to recognize, yet which dominates much of our lives and permeates even our spiritual practice?

For Jung, to be human is to have a Shadow. One of the factors that separates us from the animal world is that animals behave in what appears to be an uncontrived and immediate way. They seem to have no fabricated identity, as we experience it, that gives rise to the need to split off unacceptable behavior and impulses. Jung saw the Shadow as that aspect of the psyche that has been repressed and denied because we have wanted to hide it from the world. He implies that as we grow, we learn what is acceptable and what is not, according to the prevailing attitudes around us. We learn to repress feelings and behavior rather than risk disapproval and being judged as bad or unacceptable. An infant, rather like an animal, has little or no discrimination of what is and is not acceptable; its responses are raw, natural, and uninhibited. Inhibition grows as the ego forms more fully in consciousness and learns to separate that which serves to maintain approval from that which does not.

One of the most powerful influences over what shapes the nature of our Shadow is the cultural and spiritual atmosphere in which we grow up. If we live in a predominantly Judeo-Christian culture, this will have a particular effect upon what is found to be good and acceptable in our behavior. Our attitudes towards the body, the expression of sexuality and the emotions, and our sense of self-value will all, consequently, be strongly affected. If we then begin to explore the practice of an Eastern spiritual tradition such as Buddhism, our existing values will influence how we practice. They will also shape the way we deal with the Shadow and what is generally contained within it.

The Shadow is perhaps the most important aspect of our lives that must at some point be addressed. To assume we have no Shadow is both to become blind to ourselves and also potentially inflated. To be human is to have a Shadow, and those who are genuinely without Shadow are rare, and indeed beyond being human. The Buddha and Christ could perhaps be seen as the rare beings who finally purified the Shadow. Unfortunately, the Shadow, being by nature a blind spot, is not easy to recognize in ourselves, although others may see it. Those in positions of spiritual authority, such as teachers, are particularly vulnerable to this blindness when they are idealized by others. Once they have become caught up in the idealized view others project, it may be tempting for them to try to hide their Shadows in order to maintain their sense of authority.

As spiritual practitioners it can be painful to discover that our spiritual identity is an illusion, a fraud. This usually happens when we have had much invested in developing an idealized spiritual identity. Adopting a “spiritual” persona can give a sense that we are special and may bring much praise and veneration from others. We can create a veneer of spirituality over buried emotional problems so that we eventually convince even ourselves that we are spiritually evolved. Unfortunately, it is just a matter of time before the illusion is shattered and the Shadow emerges. It can be a humbling, sometimes painful experience to be brought back to earth rather than succeeding in living a somewhat grandiose ideal.

For several years in my mid-twenties I lived in a Buddhist community. Many of us at that time, being relatively new to Buddhist practice, had the tendency to control and repress emotions with the assumption that this was the way to practice and be virtuous. We were receiving teachings that suggested that these negative mind-states had to be tamed and controlled. We were trying to be good, peaceful, wholesome, spiritually correct practitioners, but in a particularly unhealthy way. We learned to overcome our emotions by living in a kind of spiritual straitjacket that forced strong feelings and emotions underground. We generated a very unhealthy collective Shadow and, rather than going away, these buried feelings remained and would emerge in unpleasant conflicts, negativity, and resentments.

To deny our Shadow is to live in an unreal illusion. For many in the spiritual world the Shadow holds little more than their repressed or denied emotional bad habits: the anger, jealousy, greed, and ignorance that we all suffer. For some, there may be a deeper secret that has been shut away. This often relates to trauma we have suffered at some point in our lives. It can involve deeply distorted and wounded self-beliefs that are touched when the control falls apart in private or on bad days. The illusion of a spiritual identity may cover up or compensate for this painful truth but never heals it. Healing takes place only when we return to our wounds and accept and appreciate ourselves with them. As Lama Thubten Yeshe would say, “Compassion is not idealistic”; it is our capacity to genuinely accept ourselves with our Shadow and live without illusions. With compassion, self-acceptance, and a sense of humor, we can learn to be authentic and open about our fallibilities.

The illusion of a spiritually idealized identity is often created as a flight from the pain of self-doubt and a sense of lack of worth. I recall a woman who had become a gifted and charismatic spiritual teacher whom many people valued and venerated. Her quality and depth of insight as a teacher were unmistakable, but unfortunately, much of her identity was bound up in this place of veneration and being seen as special. On occasions she would fall through the illusion that both she and her students were creating of her. She would crash into a desperate sense of self-loathing and worthlessness. From this place she would gradually drag herself back to a more realistic view of herself. The danger was of being pulled back into an illusion, created partly by her students and partly by her own pathology. Her fear of being a nobody and having no value or identity was very painful. Healing could come only when she began to accept her humanity and value herself with both her gifts and her pains. She could then potentially heal the split between the idealized image of herself as the special child she wanted to be but never felt from her parents she was, and the unlovable person she secretly believed she was. Once she had recognized this in herself, the healing could begin.

Most spiritual traditions have ideals of perfection personified in teachers, saints, and martyrs. These figures of spiritual nobility are often the cornerstones upon which traditions are built. The psychological hazard in this culture of idealized icons is that we create something against which we can tend to judge and measure ourselves. The doctrines that then become established will often set up ideals of perfection, goodness, or wholesomeness that we should follow. Rather than being guidelines to aspire to, these doctrines can reinforce our belief that we are good enough only when we achieve this ideal. Psychologically, this can set up a destructive internal conflict that pushes what is not acceptable in ourselves into the Shadow.

For a while, the ideal of the bodhisattva had this effect on me. The selfless goodness exemplified by the bodhisattva was something I felt I could only shadow. I was left feeling degenerate and low quality, selfish and unworthy—perhaps how Devadatta may have felt.

The polarity of idealized self and shadowy low esteem is one of many that become evident when one faces the Shadow. The splitting off of the Shadow is particularly evident in the puritanical attitude that characterizes much of the Western attitude to spirituality. Inevitably, the Shadow’s polar opposite of puritanical control and spiritual correctness is the anarchic, hedonistic, Dionysian instinct that wants to be free to indulge in and become intoxicated on drugs, sex, and rock and roll. Many of us experience such a conflict, which makes us swing from pole to pole, unable to find a satisfactory resolution. At one time we become pure, contained, and strict only to find a growing urge to break out and get stoned or have rampant sex.

An example of this was a young man who had been involved in yoga and meditation for many years. He was going through a period of intense Buddhist practice and study that brought into question how he was living his life. His tendency was exactly that described above. He would live for long periods with very strong ethical boundaries. He kept his life-style pure and contained. His diet was clean and healthy. He would spend most of his time mindfully cultivating good, wholesome behavior.

After a while, a deep urge would arise to break out of this straitjacket and seek what he would describe as a kind of underworld life. He wanted to dance and drink and find a woman to have sex with, sometimes a prostitute. He felt that he was unable to contain a sense of moderation. He went to extremes and would be left afterwards feeling an intense shame and guilt. Before long, he would return to his strict, puritanical life-style, having taken the edge off his hunger.

When we spoke of this it was evident that living one side of the polarity would always drive its opposite into the Shadow. He would become increasingly uncomfortable and restless until such time as he would need to break out again. Within this dilemma lay a view of Buddhism that saw purity and control and the abandonment of this side of himself as the way of practice. This left him constantly feeling bad for not being able to control himself.

We may choose to suppress the Dionysian side of our nature and drive it into the Shadow, but it will not go away.5 If we then live among Buddhists who are strongly influenced by a puritanical need to be pure and pious, this Shadow can become something of a problem. Puritanical spirituality has a strong fear of deep instinctual, archetypal forces that are wild and unruly—of the side of our nature that is potent and passionate and often seeks intoxication and sexual expression. When it takes us over we have little capacity to contain its demands for gratification. In the West, this unruly side is tied to nature gods such as Dionysus6 and Pan, who have both become associated with the Christian Devil. To the puritanical part of ourselves, this aspect of our natures must at all costs be constrained or driven out. Unfortunately, or fortunately, depending on one’s perspective, the god does not go away but remains in the Shadow. There it may feed on denial and become increasingly demonic. In time it will break through our superficial control and take us over, with sometimes devastating consequences.

Inevitably, those who live within strong moral constraints will at some point be confronted with this demon from the unconscious. Living a polarized spirituality, though, will seldom resolve the inner conflict that then ensues. The challenge of the Shadow is unavoidably one of containment and transformation. As Jung once said, the Shadow and morality are two faces of the same psychological dilemma. While we have these powerful forces within our natures, we must live with some form of ethical or moral boundary that prevents us from merely acting out our instincts. How can we live with the Shadow without forcing it into a suppressed and increasingly unhealthy place?

This dilemma has been present on my own path as a Tibetan Buddhist and has not been easy to resolve. As I have a somewhat passionate emotional nature, my spirituality tends to be more oriented to my feelings and my instinctual sense of devotion to the sacred. This devotion has been intrinsically bound up with nature and sexuality. I am well aware of the Dionysian side of my nature. The resolution has come in my exploration of Tantra, which, probably more than any other aspect of Buddhism, offers a means to understand and integrate this shadowy side of our psyches.

Perhaps this is the real challenge to our Buddhist practice. Facing the Shadow is no easy task, and different Buddhist traditions will view its challenge in different ways. For some, Mara is the manifestation of circumstances that provoke uncontrolled delusions. If we avoid these circumstances, we will not be troubled by the result. This is akin to the alcoholic avoiding pubs or bars. For others, Mara is to be encountered with a quality of awareness that could be seen as a sublime indifference. This approach is to develop a quality of detachment that can simply observe and disengage. It may be very effective; its only detriment is that it does not acknowledge the value of the forces at work in the Shadow and can lead to a tendency to be emotionally absent. The emotions are allowed to dissipate into emptiness rather than being harnessed for creative use. This detachment, however, may bring a lack of emotional engagement with life and relationships.

To the bodhisattva in the Mahayana tradition, the intention is to remain firmly engaged in the world. The Shadow is an inevitable part of that encounter and is addressed with courage, compassion, and wisdom. Whenever circumstances give rise to the shadowy sides of his or her nature, the bodhisattva seeks to transform them into the path. The aim is to recognize the challenge in any circumstance and to face the inner process, reflecting on the positive value of overcoming obstacles in order to maintain a compassionate and open heart. The Shadow is like a test to be regarded with diligence and mindfulness, never letting its nature mar the clarity of the intention to work for the welfare of others. Whatever arises is a creation of the mind and may be overcome by a change in attitude.

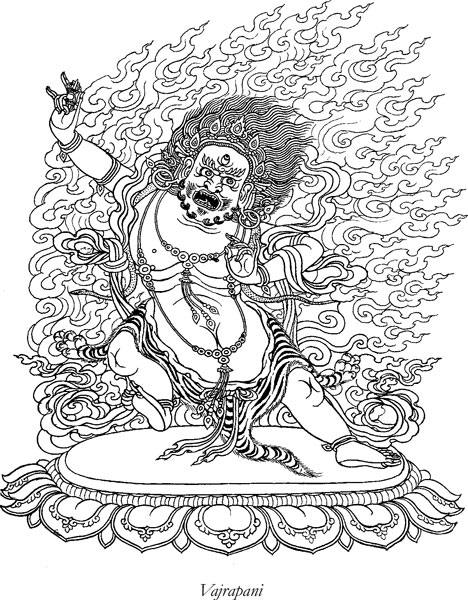

In Tantra, or Vajrayana as it is also called, the approach to the Shadow is different. The wild, potent, unruly instincts and passions are seen as the manure from which certain enlightened qualities and powers arise. The tantric approach as I have described it in The Psychology of Buddhist Tantra7 is to recognize the essential nature of the Shadow. Rather than being demonized, it is recognized as a quality of energy that can be given a channel or vehicle for transformation and integration. In Highest Yoga Tantra the deity is at the heart of this potential to transform our wild nature and its forces. These forces are dark and demonic only because they have no means to be experienced with clarity and integrated.

To integrate the Shadow we need a safe container within which transformation can occur. This puts a different emphasis on our understanding of morality. Rather than being a process of constraint, repression, and denial, morality is the clear awareness of boundaries within which the forces of the Shadow arise and transform.8 Often a meditator will experience powerful passionate energies that need to be harnessed so that their potential can be used in a creative and dynamic way. The question will always be, How is this possible?

For those who find themselves caught in this dilemma, the only option may be to respect the wild god that runs through their psyches. Simply compressing it into a spiritual straitjacket does not heal or transform it. Finding a path that provides a means of transformation is vital if the Shadow side of our nature is not to become a growing source of psychological ill health. As Jung suggested, there are gods in our psychological diseases.

For those who have a strong Dionysian aspect to their nature, the purity and piety of spiritual correctness will always feel like an anathema. Rather than becoming alienated by spiritual mores laid down by those who live a controlled, pious, and abstinent life, it becomes important to find a spiritual way that fits. For some, this may be the unorthodox following of the gods of intoxication and spiritual ecstasy. There have been many such mystery traditions in both the East and the West. The Shivaite tradition of the Hindu Tantras and the practice of particular deities of Buddhist Tantra provide a way to bring this aspect of the psyche back into the temple rather than repressing its nature. There, it can be venerated in its particular way as a profound means of transformation and awakening.

In India, the tantric approach was particularly associated with a group of Indian Buddhist adepts known as the eighty-four mahasiddhas. These were tantric yogis who were renowned for the power of their realizations. Their biographies9 show that many of them were rejected from the monastic tradition because they would not conform to the expectations of the institution. Their behavior led them to be cast as the Shadow of the institution and, as such, scapegoated for their lack of complicity. Their ejection from the monastery, however, served to bring their hidden qualities as remarkable holy beings to public attention.

One such example was of a monk at Nalanda, a famous monastery in India established soon after the Buddha’s time. His name was Virupa and he spent many years practicing a particular Tantra, which he felt was not giving him results. In despair one day he threw his ritual implements into the toilet. That night he received a vision of a dakini who initiated him into the Hevajra Tantra. With only a brief practice he attained the quality of Hevajra and from that time onwards he was heard to have female voices in his cell. This caused the other monks to question his morality. They accused him of breaking his vows and began to revile him as a degenerate. In disgust one day he said it was clear the monastery no longer wished to have him there, and he simply walked through the wall and left. The monks were angry with him and threw stones at him, which transformed into flowers and settled around him.

Virupa wandered away from Nalanda and came to a land where the population had a reputation for drinking alcohol and having no spiritual life. He entered a shop that sold alcohol and began to drink. He impressed the locals with his capacity to consume vast quantities. When asked to pay, he said he would do so when the sun’s shadow passed a certain place. He continued to drink, but the sun’s shadow failed to move. The locals, in amazement, realized this man was very special. Eventually he was asked to explain his spiritual qualities, and he began to teach. Virupa became the originator of the Tibetan lineage known as the Sakya.

There are many other examples of famous adepts in India who did not conform to the traditional ideals of spiritual behavior and who thus came into conflict with society’s need for purity and piety. Despite this, their unorthodox practice demonstrated that the Shadow contains energies and forces which, when harnessed through intense practice, give rise to extraordinary realization.