Life Aboard a Cruise Ship

Modern ships are designed for safety, passenger comfort and fuel efficiency.

The waters of Northern Europe have been plied over the centuries by craft ranging from Viking longships to square-rigged frigates to dreadnought battleships. Naval power has been critical to the rise and fall of nearly every European empire, and a nation’s merchant marine was usually the lifeblood of its trade-based wealth.

Modern ships navigating northern European waters must deal not only with the natural elements – strong currents, contrary winds and, in early spring, ice-clogged ports – but with the added challenge of heavy marine traffic. The North Sea and English Channel are among the busiest waters in the world, with over 400 ships using the Channel every day.

The constant flow of freighters, car ferries and other commercial traffic in the Channel and the Strait of Dover has resulted in serious ship collisions in the past and the movements of vessels are now monitored by coast guard radar stations in English and French ports. Using the Traffic Separation System, ships are always kept at a specific distance from one another while transiting these waters.

The Baltic Sea also has significant vessel traffic, but its waters are not as constricted, so separation of ships is not such an issue.

Ships are pushed through the water by the turning of propellers, two of which are mounted at the stern. A propeller is like a screw threading its way through the sea, pushing water away from its pitched blades. Props are 15 to 20 feet in diameter on large cruise ships and normally turn at 100 to 150 revolutions per minute. It takes a lot of horsepower – about 60,000 on a large ship – to make these propellers push a ship along. The bridge crew can tap into any amount of engine power by moving small levers that adjust the propeller blades to determine the speed of the ship. Most modern ships use diesel engines to deliver large amounts of electricity to motors that smoothly turn the propeller shafts. Ship vibration is minimal using these sophisticated systems to deliver power. Some ships use electric motors mounted on pods hung from the stern of the ship, like huge outboard engines. These pods can swivel 360 degrees.

The average speed at which cruise ships travel is 21 to 24 knots. Distances at sea are measured in nautical miles (1 nautical mile = 1.15 statute miles = 1.85 kilometres).

The majority of cruise ships currently deployed to Europe were built in the last decade or two. This proliferation of newbuilds, along with ongoing retrofitting and refurbishing of ships, has resulted in an ever-expanding array of shipboard amenities – from health spas and water slides to movie theatres and specialty restaurants. Cabins, formerly equipped with portholes, now are fitted with picture windows or sliding glass doors that open onto private verandahs.

Modern cruise ships are quite different from those of the Golden Age of ocean liners, which were designed for the rigours of winter storms in the North Atlantic. Ships built today are generally taller, shallower, lighter and powered by smaller, more compact engines. Although their steel hulls are thinner and welded together in numerous sections, modern ships are as strong as the ocean liners of yesterday because of advances in construction technology and metallurgy.

A ship’s size is determined by measurements that result in a figure called gross tonnage (internal volume). There are approximately 100 cubic feet to a measured ton. Most new ships being built today are over 100,000 tons and carry several thousand passengers. At the stern of every ship, below its name, is the ship’s country of registry, which is not necessarily where the cruise company’s head office is located. Certain countries grant registry to ships for a flat fee, and ships often fly these ‘flags of convenience’ for tax reasons.

Located many decks below passenger cabins is the engine room, a labyrinth of tunnels, catwalks and bulkheads connecting and supporting the machinery that generates the vast amount of power needed to operate a ship. A large, proficient crew keeps everything running smoothly, but this is a far cry from the hundreds once needed to operate coal-burning steam engines used before the advent of diesel fuel.

A ship lying to anchor always has officers on watch on the bridge.

Technical advancements in the last 50 years have helped reduce fuel consumption and improve control of the ship. These include the bow bulb, stabilizers and thrusters. The bow bulb is just below the waterline and displaces the same amount of water that would be pushed out of the way by the ship’s bow. This virtually eliminates a bow wave, resulting in fuel savings as less energy is needed to push the ship forward. Stabilizers are small, wing-like appendages that protrude amidships below the waterline and act to dampen the ship’s roll in beam seas. Thrusters are port-like openings with small propellers at the bow and sometimes also at the stern, which push the front or rear of the ship as it is approaching or leaving a dock. Thrusters have virtually eliminated the need for tugs in most situations when docking.

The ship’s captain on the bridge.

The bridge (located at the bow or front of the ship) is an elevated, enclosed platform bridging (or crossing) the width of the ship with an unobstructed view ahead and to either side. It is from the ship’s bridge that the highest-ranking officer, the captain, oversees the operation of the ship. The bridge is manned 24 hours a day by two officers working four hours on, eight hours off, in a three-watch system. They all report to the captain, and their various duties include recording all course changes, keeping lookout and making sure the junior officer keeps a fresh pot of coffee going. The captain does not usually have a set watch but will be on the bridge when the ship is entering or leaving port, and transiting a channel. Other conditions that would bring the captain to the bridge would be poor weather or when there are numerous vessels in the area.

An array of instrumentation provides the ship’s officers with pertinent information. Radar is used most intensely in foggy conditions or at night. Radar’s electronic signals can survey the ocean for many miles, and anything solid – such as land or other boats – appears on its screen. Radar is also used for plotting the course of other ships and for alerting the crew of a potential collision situation. Depth sounders track the bottom of the seabed to ensure the ship’s course agrees with the depth of water shown on the official chart.

The helm on modern ships is a surprisingly small wheel. An automatic telemotor transmission connects the wheel to the steering mechanism at the stern of the ship. Ships also use an ‘autopilot’ which works through an electronic compass to steer a set course. The autopilot is used when the ship is in open water.

Other instruments monitor engine speed, power, angle of list, speed through water, speed over ground and time arrival estimations. When entering a harbor, large ships must have a pilot on board to provide navigational advice to the ship’s officers. When a ship is in open waters, a pilot is not required.

A tender transports passengers ashore at the port of Grundarfjordur Iceland.

At some ports, the ship will anchor off a distance from the town and passengers are tendered ashore with the ship’s launches. People on organized shore excursions will be taken ashore first, so if you have booked an excursion you will assemble with your group in one of the ship’s public areas. Passengers not on an excursion should wait 45 minutes to an hour before attempting to board a tender to avoid long line-ups.

Ships docked at Tallinn.

Cruise ships are one of the safest modes of travel. The International Maritime Organization maintains high standards for safety at sea, including regular fire and lifeboat drills, as well as frequent ship inspections for cleanliness and seaworthiness.

Cruise ships must adhere to a law requiring that a lifeboat drill take place within 24 hours of embarkation, and most ships schedule this drill just before leaving port. Directions are displayed in your cabin, and staff are on hand to guide passengers through the safety drill.

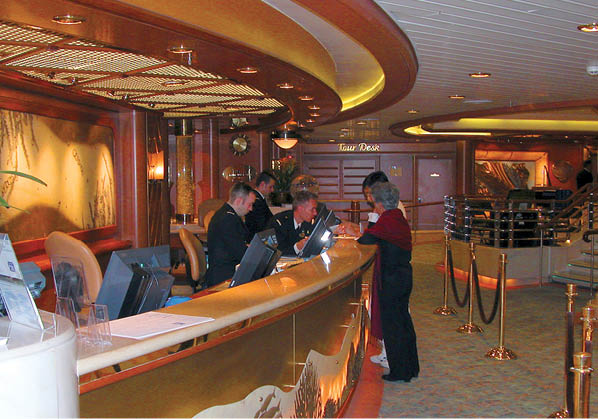

A ship’s hotel manager oversees all of the service staff.

The Front Desk (or Purser’s Office) is the pleasure centre of the ship. And, in view of the fact that a cruise is meant to be an extremely enjoyable experience, it is fitting that the Hotel Manager’s rank is second only to that of the Captain. In terms of staff, the Hotel Manager (or Passenger Services Director) has by far the largest. It is his responsibility to make sure beds are made, meals are served, wines are poured, entertainment is provided and tour buses arrive on time – all while keeping a smile on his or her face. Hotel managers generally have many years’ experience on ships, working in various departments before rising to this position. Most initially graduate from a college program in management and train in the hotel or food industries, where they learn the logistics of feeding hundreds of people at a sitting.

A Hotel Manager’s management staff includes a Purser, Food Service Manager, Beverage Manager, Chief Housekeeper, Cruise Director and Shore Excursion Manager. All ship’s staff wear a uniform and even if a hotel officer doesn’t recognize a staff member, he will know at a glance that person’s duties by their uniform’s color and the distinguishing bars on its sleeves. The hotel staff on cruise ships come from countries around the world.

The front desk handles all passenger queries and accounts.

Upon arrival at the cruise pier, you will be directed to a check-in counter and asked to offer up a credit card to be swiped for any onboard expenses. In exchange, you will receive a personalized plastic card with a magnetic strip. This card acts both as your onboard credit card and the door key to your stateroom. It is also your security pass for getting off and on the ship at each port of call. Carry this card with you at all times.

An outside stateroom with balcony.

Cruise ship cabins – also called staterooms – vary in size, from standard inside cabins to outside suites complete with a verandah. Whatever the size of your accommodation, it will be clean and comfortable. A telephone and television are standard features in cabins, and storage space includes closets and drawers ample enough to hold your clothes and miscellaneous items. Valuables can be left in your stateroom safe or in a safety deposit box at the front office, also called the purser’s office.

The main dining room on a large ship.

If your budget permits, an outside cabin – especially one with a verandah – is preferable for enjoying the coastal scenery and orienting yourself at a new port. When selecting a cabin, keep in mind its location in relation to the ship’s facilities. If you’re prone to seasickness, cabins located on lower decks near the middle of the ship will have less motion than a top outside cabin near the bow or stern. If you have preferences for cabin location, be sure to discuss these with your cruise agent when booking. Cruise lines often reward passengers who book early with free upgrades to a more expensive stateroom.

A ship’s specialty restaurant.

Both casual and formal dining are offered on the large ships, with breakfast and lunch served in the buffet-style lido restaurant or at an open seating in the main dining room. Traditionally, dinner was served at two sittings in the main dining room and passengers were asked to indicate their preference for first or second sitting. While this traditional two-sitting format is still offered on the large ships, flexible dining times are also offered. Luxury cruise lines usually have one open seating for dinner. Most large ships also offer alternative dining – small specialty restaurants that require a reservation and for which there is usually a surcharge (about $20-$30 per person). Room service is also available, free of charge, for all meals and in-between snacks.

Lone jogger gets an early start to the day.

There are so many things to do on a cruise ship, you would have to spend a few months aboard to participate in every activity and enjoy all of the ship’s facilities. A daily newsletter, slipped under your door, will keep you informed of all the ship’s happenings. If exercise is a priority, you can swim in the pool, work out in the gym, jog around the promenade deck, join the aerobics and dance classes or join in the pingpong and volleyball tournaments. Perhaps you just want to soak in the jacuzzi or treat yourself to a massage and facial at the spa.

Putting about on the Lido Deck.

Stop by the library if you’re looking for a good book, a board game or an informal hand of bridge with your fellow passengers. Check your newsletter to see which films are scheduled for the movie theatre or just settle into a deck chair, breathing the fresh sea air. Your days on the ship can be as busy or as relaxed as you want. You can stay up late every night, enjoying the varied entertainment in the ship’s lounges, or you can retire early and rise at dawn to watch the ship pull into port. When the ship is in port, you can remain onboard if you wish or you can head ashore, returning to the ship as many times as you like before it leaves for the next port. Ships are punctual about departing, so be sure to get back to the ship at least a half hour before it is scheduled to leave.

Children enjoy the facilities on contemporary ships.

Children and teenagers are welcome on most cruise ships, which offer an ideal environment for a family vacation. Youth facilities on the large ships usually include a playroom for children and a disco-type club for teenagers. Supervised activities are offered on a daily basis, and security measures include parents checking their children in and out of the playroom. Kids have a great time participating in activities ranging from ball games to arts and crafts, all overseen by staff with degrees in education, recreation or a related field. Each cruise line has a minimum age for participation (usually three years old), and some also offer private babysitting. Youth facilities and programs vary from line to line, and from ship to ship.

Celebrating a special occasion.

There are few additional expenses once you board a cruise ship. Your stateroom and all meals (including 24-hour room service) are paid for, as are any stage shows, lectures, movies, lounge acts, demonstrations and other activities held in the ship’s public areas. If you make use of the personal services offered on board – such as dry cleaning or a spa treatment or a yoga class – these are not covered in the basic price of a cruise. Neither are any drinks you might order in a lounge. You will also be charged for any wine or alcoholic beverages you order with your meals.

The view from the ship’s lounge.

Gratuities are extra, with each cruise line providing its own guidelines on how much each crewmember should be tipped – provided you are happy with the service. (On luxury lines, gratuities are usually included in the all-inclusive fare.) A general amount for gratuities is US $3.50 per day per passenger for both your cabin steward and dining room steward, $2 per day for your assistant waiter and $1 per day for the dining room management. Most cruise lines offer a service that automatically bills a daily amount for gratuities (about $10 per passenger) to your shipboard account, which can be adjusted at your discretion.

A ship’s central atrium.

On most ships passengers sign for incidental expenses that are itemized on a final statement and slipped under the cabin door during the last night of the cruise and settled by pre-approved credit card or cash. Check your account balance (which can usually be accessed on your stateroom television) before the last day of your cruise and if there is a discrepancy visit the Front Desk to sort things out to avoid lineups. Lineups at this desk can be long on disembarkation day.

Sunset at the ship’s rail.