“COMMUNISM IS SOVIET POWER PLUS THE ELECTRIFICATION OF THE WHOLE COUNTRY”

Crash Industrialization in the Soviet Union

IN DECEMBER 1929, PHILIP ADLER, A REPORTER FOR THE Detroit News, visited Stalingrad, on the Volga River in southwestern Russia (until 1925 called Tsaritsyn), where the government of the Soviet Union was erecting a huge new tractor factory on a muddy, treeless field that had been used for growing melons. The factory held special interest for Motor City readers because American companies and workers—many from Detroit—were heavily involved in its planning and operation. Albert Kahn served as the overall architect, the Frank D. Chase Company laid out the foundry, and R. Smith, Incorporated, designed the forge shop. McClintic-Marshall Products Company fabricated the beams and trusses. Most of the production equipment was made in the United States, and the Soviets hired several hundred Americans to work at the plant, in many cases as foremen or supervisors.

Before going to the factory site, a half hour out of town, Adler visited the city center, where in the market he found “the familiar figures of the tinker, the cobbler and the dealers in second hand clothing and furniture who employ the most primitive methods of manufacture and salesmanship. The ox team, the camel and the biblical ass rival the horse as mediums of transportation.” From a minaret among the church cupolas came the cry “ ‘Allah Ho Akbar!’—Allah is powerful!” But when Adler got to the construction site, the watchword everywhere was “ ‘Amerikansky Temp’ or ‘American tempo’ ” and the slogan plastered about was “To catch up with and surpass America.” The following summer, with the plant beginning to turn out its first tractors, Margaret Bourke-White arrived after an arduous journey, taking what would become one of her most iconic photographs, of three workers on a newly finished tractor coming off an assembly line.1

Figure 5.1 Margaret Bourke-White’s iconic 1931 photograph, Stalingrad Tractor Factory.

The Tractorstroi (“tractor factory”) in Stalingrad was part of a feverish drive by the Soviet Union to rapidly industrialize, boosting its standard of living and increasing its defensive capacity on the road to creating a socialist society. Most Bolshevik leaders believed that a socialist or communist society could be achieved in Russia—a poor and economically backward country—only after significant industrial development. Seizing political power was not enough. “There can be no question of . . . communism,” Vladimir Lenin declared in 1920, “unless Russia is put on a different and a higher technical basis than that has existed up to now. Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country, since industry cannot be developed without electrification.” And it was a particular type of industrialization Lenin and his comrades had in mind, “large-scale machine production.”2

It took time before the Soviet Republic could launch a major industrialization effort, but by the late 1920s a detailed plan had been adopted. In 1929, on the twelfth anniversary of the October Revolution, Joseph Stalin wrote, “We are advancing full steam ahead along the path of industrialization—to socialism, leaving behind the age-old ‘Russian’ backwardness. We are becoming a country of metal, a country of automobiles, a country of tractors.”

Industrial behemoths were key to the Soviet effort to leap from “The ox team, the camel and the biblical ass” to “a country of metal, a country of automobiles, a country of tractors.” The First Five-Year Plan, begun in 1928, centered on a series of very large scale factory and infrastructure projects, including three huge tractor factories, a big automobile plant in Nizhny Novgorod, immense steel complexes at Magnitogorsk and Kuznetsk, the Dnieporstroi hydroelectric dam, the Turksib railway connecting Kazakhstan with western Siberia, and the Volga-Don canal. Lacking the technical expertise and industrial resources for creating and equipping projects of such size and sophistication, the Soviets turned heavily to the West, especially the United States, for engineers, construction and production experts, and machinery, adopting the techniques of scientific management and mass production and in some cases creating virtual replicas of facilities in the United States. As Stephan Kotkin wrote in his landmark history of Magnitogorsk, for the communists, “The dizzying upheaval that was Soviet industrialization was reduced to the proposition: build as many factories as possible, as quickly as possible, all exclusively under state control.” In the Soviet Union, just as in the United States, the giant factory came to be equated with progress, civilization, and modernity.3

But the Soviet Union was a very different place than the United States. Would the factory itself be different there? Would it have a different social significance? In 1927, Egmont Arens, an editor of the left-wing journal New Masses, reviewing a play, The Belt, which demonized assembly line production, remarked, “The Belt is something that has got to be faced even by advocates of a workers’ state. Right now Russia is installing modern industrial plants of her own. Are the horrible things that The Belt does to minds and bodies of workers inevitable? Or is there a difference between high pressure production in Socialist Russia and Henry Ford’s Detroit?”4

The factory had developed largely as a means for industrialists and investors to make money for themselves. Though it was sometimes freighted with moral imperatives and claims of social good, its physical design, internal organization, technology, and labor relations were determined primarily by the desire to maximize profits.5 What did it mean to have a factory in a society where profits, in the usual sense, did not exist, where all large-scale productive entities belonged to a government that, at least in theory, served as the agent of the people, especially the working class? Could and should the capitalist factory, as a technical, social, and cultural system, simply be moved into a socialist society? Were methods like scientific management and the assembly line, designed to increase efficiency and labor productivity in order to boost profits, appropriate for a society in which the needs of workers and the well-being of the entire population were declared paramount?

The Soviet Union differed from the United States not only in its ideology but also in its level of economic development. Before the 1917 revolution, Russia had been an overwhelmingly agricultural society. What industry it did have was severely disrupted by the revolution and the civil war that followed. Could large, technically advanced industrial facilities successfully operate in such an environment, short-cutting the long process of economic development that had occurred in Western Europe and the United States? Could a heroic effort to leap directly to large-scale industrialization stimulate broad economic growth, or would chaos ensue from the lack of needed material inputs, logistics, and worker and managerial skills?

Questions about the role of the giant factory in economic development and social structure remain alive today, both in the few remaining countries that call themselves communist—most importantly China and Vietnam—and in the capitalist world. With much of the world’s population still living in poverty, the issue of how to raise living standards remains a central economic, political, and moral concern. What role should the giant factory play in the effort to achieve broad material and social well-being? What price should industrial workers pay for social abundance?

Some of the answers to these knotty questions began to emerge during the 1930s, from the muddy fields on the outskirts of Stalingrad and from other sites like it across the Soviet Union. The experience with the American-style giant factory proved crucial not only in shaping the history of the Soviet Union but also in defining a path for development for much of the world in the decades after World War II. Stalinist industrial giantism, for better and for worse, became one of the main paths for trying to achieve prosperity and modernity, a Promethean utopianism that mixed huge social ambitions with enormous human suffering.

“Marxism Plus Americanism”

In the twentieth century, American production techniques and managerial methods—what came to be called “Americanism”—commanded considerable interest in Europe. Some of it was technical, in high-speed machining and the high-strength metals it required, the standardization of products, the use of various kinds of conveyance devices, and the mass-production system that these developments made possible. But interest was at least as great in the ideology associated with advanced manufacturing, the promise that with productivity gains the income of workers could go up even as profits rose, thereby dissipating class conflict and social unrest.6

As avatars of scientific management and mass production, Frederick Winslow Taylor and Henry Ford became well-known and well-regarded figures in Europe. By the early twentieth century, Taylor’s writings had been translated into French, German, and Russian. In the early 1920s, Ford displaced Taylor as the icon of Americanism, as worker criticism of Taylorist management grew and the wonders of the assembly line and the Model T became better known abroad. In Germany, Ford’s autobiography, My Life and Work, translated in 1923, sold more than two hundred thousand copies.

Though Americanism as a technical and ideological system had considerable influence all across Europe, perhaps surprisingly its greatest impact occurred in the Soviet Union. The groundwork was laid before the revolution. What industry Russia had tended to be highly concentrated, with quite a few large factories, some foreign-owned and operated with the help of foreign experts who were aware of the latest trends in management thinking, including those associated with Americanism. In addition, at least a few Russian socialists, most importantly Lenin, knew about scientific management and thought about its implications.

In his first comments about scientific management, while in exile in 1913, Lenin echoed critiques common among American and European unionists and leftists, seeing its “purpose . . . to squeeze out of the worker” more labor in the same amount of time. “Advances in the sphere of technology and science in capitalist society are but advances in the extortion of sweat.” Three years later, he plunged deeper into scientific management in preparation for writing Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, reading a German translation of Taylor’s book Shop Management, a book on the application of the Taylor system, and an article by Frank Gilbreth on how motion studies could increase national wealth. In the end, he never discussed management techniques in Imperialism, but his notes from the time indicate a view of scientific management in keeping with the general tenor of the book, in which capitalist advances, whatever their motives, were portrayed as laying the basis for a socialist transformation, in line with Marx’s portrayal of capitalism as an antechamber to a socialist economy.7

The 1917 revolution radically changed the context for Russian thinking about scientific management. Instead of critiquing existing social arrangements and defending workers, Russian communists and their allies now found themselves facing the almost overwhelming challenge of restoring the economy of a country depleted and disrupted by war and revolution to the point of famine, even as they fought a civil war and tried to consolidate their power. For Lenin, scientific management became a necessary tool to increase productivity and overcome economic backwardness, a prelude to establishing a socialist society:

The Russian is a bad worker compared with workers of the advanced countries. Nor could it be otherwise under the tsarist regime and in view of the tenacity of the remnants of serfdom. The task that the Soviet government must set the people in all its scope is—learn to work. The Taylor system, the last word of capitalism in this respect, like all capitalist progress, is a combination of the subtle brutality of bourgeois exploitation and a number of its greatest scientific achievements in the field of analyzing mechanical motions during work, the elimination of superfluous and awkward motions, the working out of correct methods of work, the introduction of the best system of accounting and control, etc. The Soviet Republic must at all costs adopt all that is valuable in the achievements of science and technology in this field. . . . We must organize in Russia the study and teaching of the Taylor system and systematically try it out and adapt it to our purposes.

Lenin even suggested bringing in American engineers to implement the Taylor system.8

Lenin’s backing helped legitimize scientific management as a practice and ideology in the new Soviet Republic. Exigency accelerated its adoption. One of its earliest adoptions came in railroad shops and armaments factories during the civil war, when keeping train engines operating and producing arms were literally matters of life and death for the revolution. As Commissar of War, Leon Trotsky embraced Taylorism as a “merciless” form of labor exploitation but also “a wise expenditure of human strength participating in production,” the “side of Taylorism the socialist manager ought to make his own.” Desperate to increase production, the Soviet government adopted piecework as a general practice and set up a Central Labor Institute to promote means of increasing labor productivity, including time and motion studies and other forms of scientific management.9

The embrace of Taylorism did not go unchallenged. As in the West, many workers and trade unionists opposed the imposition of more stringent work norms through piecework and so-called scientific methods, especially if workers themselves did not play a role in establishing and administrating them. And there were more sweeping ideological objections, too, centered on the relationship between building a new kind of society and using capitalist methods.

On the one side were trade unionists, “Left Communists,” and, later, members of the “Workers Opposition” within the Communist Party, who believed that a socialist society required different social structures of production than had developed under capitalism, with greater worker participation and authority on the shop floor, in managing enterprises, and in determining methods of production. These critics of scientific management wanted to devise ways to increase productivity without further exploiting workers, opposing the extreme division of labor that transformed “the living person into an unreasoning and stupid instrument.” To simply adopt methods workers had long criticized under capitalism would negate the meaning of the revolution.

On the other side were those who viewed capitalist production methods as simply techniques that could be used to any end, including the creation of wealth that would be the property of the whole society under a socialist regime. Alexei Gastev, a one-time worker-poet who became the secretary of the All-Russia Metal Workers’ Union, the head of the Central Labor Institute, and the leading Soviet proponent of scientific management, wrote in 1919, “Whether we live in the age of super-imperialism or of world socialism, the structure of the new industry will, in essence, be one and the same.” Like other Soviet supporters of scientific management, Gastev saw in Russian culture, especially among peasants and former peasants who had entered industry, an inability to work hard at a steady pace, instead alternating spurts of intense labor with periods of little if any work (the same complaint early English and American factory owners had about their workers). American methods and an American sense of speed would provide a cure. Trotsky gave intellectual and political weight to the case for adopting capitalist methods, advocating the use of the most advanced production techniques, regardless of their origin. Labor compulsion, necessary during the transition to socialism, he contended, had different significance when used in the service of a workers’ state than for a capitalist enterprise (an argument that made little headway with many Soviet trade unionists).10

The dispute over scientific management was largely resolved at the Second All-Union Conference on Scientific Management, held in March 1924. The participation by top communist leaders in the extensive public debate that preceded it was a measure of the importance of the question of the use of capitalist management methods in the Soviet Union. By and large, the conference came out in support of Gastev and the wide application of scientific management, reflecting the demographic and economic circumstances of the period. The prerevolutionary and revolutionary-era skilled working class, the natural center for opposition to Taylorism, had been all but decimated by war, revolution, and civil war, with many of its survivors co-opted into leadership positions in the government and the party. The main challenge in trying to raise Soviet productivity was not squeezing more labor out of experienced, skilled workers but getting useful labor out of new workers with little or no industrial experience, for which scientific management, with its stress on the simplification of tasks and detailed instructions to workers, seemed well suited.11

It is not clear how much actual impact the endorsement of scientific management had on Soviet industry, at least in the short run. The Soviet Union lacked the experts, equipment, and experience to implement the methods advocated by Taylor and his disciples. Gastev’s institute, the center of scientific management, did not have even basic equipment, conducting simplistic experiments of little practical significance. Much of its work consisted of exhorting workers: “Sharp eye, keen ear, alertness, exact reports!” Gastev urged. “Mighty stroke! Calculated pressure, measured rest!” Many Soviet managers adopted piecework pay, but unless accompanied by detailed studies and reorganization that did nothing to increase efficiency, instead simply inducing workers to work harder using existing methods. Some scientific management techniques did become common, like the use of Gantt charts for production planning, as over time Soviet management journals and training institutes spread the Taylorist gospel. But the immediate importance of the endorsement of scientific management lay not in the field but in opening the door to a broader embrace of Western methods and technologies, which would soon lead to a crash program to re-create the American-style giant factory.12

An early experiment came in the textile industry, in cooperation with an American labor union. In 1921, Sidney Hillman, the president of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers (ACW), after meeting with top Bolshevik leaders and Soviet trade unionists, signed an agreement to set up the Russian-American Industrial Corporation (RAIC), a joint enterprise with the Russian Clothing Workers syndicate, which ended up controlling twenty-five garment and textile factories that employed fifteen thousand workers. The deal came just as the Soviet Union was abandoning “War Communism,” the direct state control and partial militarization of the economy during the civil war, turning to a partial restoration of private ownership and market relations under the “New Economic Policy (NEP).”

The ACW proved a perfect partner for what in effect was a state-sponsored cooperative enterprise, meant to deploy the most advanced American equipment and management techniques in the restoration of the Russian garment industry. Many members and leaders of the heavily Jewish ACW, including Hillman, had emigrated from the Russian Empire, infected with the same radicalism that culminated in the revolution. Under Hillman’s leadership, though, the ACW had become increasingly practical in its policies, seeing in scientific management a way to improve productivity in a fragmented, often technologically primitive industry, creating the basis for upgrading worker living standards. The trade-off the ACW insisted on was union involvement in setting production norms and piecework rates and a system of neutral arbitration to resolve grievances. But the union affinity with scientific management was not strictly pragmatic; as Hillman’s biographer Steve Fraser wrote, “the ACW elite was firmly implanted in those socialist traditions that affixed the tempo and timing of socialism to the inexorable rhythms of industrial and social developments under capitalism.”

Through RAIC, the ACW brought to the Soviet garment industry not only Western capital but more importantly advanced equipment and expertise, including leading proponents of scientific management, factory managers the union had dealings with in the United States, and skilled workers familiar with joint union-management efforts at Taylorization. In short order, RAIC could boast of factories that matched the most advanced plants in the United States in their equipment, productivity, and progressive labor relations.13

Flirting with Ford

The NEP, which RAIC was part of, reanimated the Soviet economy. But it failed to fully restore Soviet industry to prerevolutionary levels of production, let alone fulfill the promise of the revolution to improve life for tens of millions of workers and peasants. In October 1925, Soviet industry still produced only 71 percent of pre–World War I Russian output. Fairly small investments under NEP were able to boost industrial output because there was considerable unused capacity. But by the mid-1920s, with utilization much higher, fewer possibilities remained for quick gains and possible reversals loomed; little capital investment for a decade meant that much of the industrial machinery in the country had reached or exceeded its expected service life. Further advances would require heavy investment in plant renovation, construction, and equipment.14

For most Soviet planners and political leaders, that meant staking the future of the revolution on large-scale industrial and infrastructure projects, though they disagreed sharply about the means and pace of investment. The Marxist tradition had long associated progress and modernity with the concentration of capital and mechanization. The prerevolutionary Russian industrial experience also influenced the Soviet sense of scale. In 1914, over half of Russian factory workers were employed in plants with more than five hundred workers, compared to less than a third in the United States. On the eve of the revolution, Petrograd had a cluster of very big government-controlled armament factories, some with well over ten thousand workers, as well as a few giant private plants, including the Putilov metalworking complex, with around thirty thousand workers (where a strike helped kick off the revolt against the Tsar).15

Many Soviets credited the success of the United States, which they saw as an exemplar, to its adoption of standardized products and large industrial complexes. As in Western Europe, Henry Ford was well known in the Soviet Union, seen as a living embodiment of the most advanced social, technical, and economic developments. By 1925, the Russian translation of My Life and Work had gone through four printings. But even more important in spreading Ford’s fame was his tractor, the Fordson.

Before World War I, there were only about six hundred tractors spread across the vast domains of Russia. Believing the upgrading of agricultural productivity central to the revolution, starting in 1923 the Soviet Union began importing tractors in growing numbers, largely Fordsons. By 1926, 24,600 orders for Ford tractors had been placed. The Soviet Union also imported some Model Ts. A pipeline from River Rouge to the Russian steppes and cities had been opened.

In 1926, the Soviet government asked Ford to send a team to see how it could improve the maintenance of tractors, a large percentage of which, at any given time, were inoperable because of poor servicing, a lack of quality replacement parts, and inefficient labor. Also, the Soviets wanted to explore the possibility of Ford setting up a tractor factory in Russia. Already, they were trying, not very successfully, to produce knock-offs of the Fordson on their own. After spending four months touring the Soviet Union, a Ford delegation recommended against building a factory, fearful of political interference in operations and possible future expropriation. Undeterred, Soviet officials still hoped for Ford-style factories to make much-needed agricultural equipment and motor vehicles.16

By then, Ford methods did not evoke great controversy in the Soviet Union. The debate over Taylorism already had led to the endorsement of the use of capitalist methods. Also, Fordism less directly challenged the small but influential cadre of skilled metalworkers than scientific management, since, even with assembly lines, craftsmen would be needed to make tools and dies and maintain machinery. After touring the Soviet Union in 1926, William Z. Foster reported “revolutionary workers are . . . . taking as their model the American industries. In Russian factories and mills . . . . It is all America, and especially Ford, whose plants are generally considered as the very symbol of advanced industrial technique.” “Fordizatsia”—Fordisation—became a favorite Soviet neolism.17

Still, there was some opposition to Fordism by left-wing critics who thought the adoption of methods designed to extract more labor from workers went against the fundamental socialist project of diminishing the exploitation and alienation of the working class. One of the sharpest ripostes to them came from Trotsky, a leading advocate of the adoption of Ford methods, just as he had been a leading advocate of the adoption of scientific management. In a 1926 article, he bluntly declared, “The Soviet system shod with American technology will be socialism. . . . American technology . . . will transform our order, liberating it from the heritage of backwardness, primitiveness, and barbarism.”

Trotsky thought the assembly line, or conveyor method as he called it, would supplant piecework as a capitalist means of regulating labor, replacing an individualized mode with a collective one. Socialists needed to adopt the conveyor, too, he argued, but under their control it would be different, since the pace and hours of work would be set by a workers’ regime. Nonetheless, he acknowledged that by its very nature the assembly line degraded human labor. In perhaps the most powerful argument ever made in defense of the Fordist factory, at least from a point of view other than that of those who profited from it, Trotsky answered a question he had been asked, “What about the monotony of labor, depersonalized and despiritualized by the conveyor?” “The fundamental, main, and most important task,” he replied, “is to abolish poverty. It is necessary that human labor shall produce the maximum possible quantity of goods. . . . A high productivity of labor cannot be achieved without mechanization and automation, the finished expression of which is the conveyor.” Just like Edward Filene, Trotsky claimed “The monotony of labor is compensated for by its reduced duration and its increased easiness. There will always be branches of industry in society that demand personal creativity, and those who find their calling in production will make their way to them.” Then came a final flourish: “A voyage in a boat propelled by oars demands great personal creativity. A voyage in a steamboat is more ‘monotonous’ but more comfortable and more certain. Moreover, you can’t cross the ocean in a rowboat. And we have to cross an ocean of human need.”18

Just how to cross that ocean of need became the subject of an intense debate among Soviet leaders in the mid-1920s. The Bolshevik assumption always had been that the survival of their revolution would depend on the spread of socialism to advanced countries in Western Europe, which would then help Russia develop. But by a half-dozen years after World War I, it was clear that in the near future there would be no triumphant revolutions elsewhere. For economic development, the Soviet Union would have to depend on its own very limited resources.

Some Soviet leaders, including Nikolai Bukharin, argued that under the circumstances the best road forward lay in modest, balanced growth, driven by upgrading the agricultural sector. Increased peasant income would expand the market for consumer goods, which could be met through investments in light industry. Heavy industry would have to grow slowly.

Others wanted heavy industry to take the lead, with a faster pace of industrialization and economic growth. In part, they were driven by fears that the Western powers would again use their military forces to try to overthrow the Soviet regime, as they had during the civil war, necessitating the rapid development of an industrial base that could support a powerful army. They also feared placing the fate of the economy in the hands of a peasantry that wavered in its allegiance to the Soviet regime, withholding grain and other goods when prices were low or when there were too few consumer goods available to spend their money on. Instead, advocates of rapid industrialization, including Trotsky, sought to extract more wealth from the peasantry, if need be through levies, selling grain and raw materials abroad to finance industrialization.

A Communist Party congress in late 1927 balanced the two positions. But during the next two years, as a detailed Five-Year Plan for the economy was worked out, policy shifted toward the “super-industrializers” and then went far past even their most ambitious goals. The final plan called for a pace of industrialization unprecedented in human history, in half a decade doubling the fixed capital of the country and increasing iron production fourfold.

The swing coincided with Joseph Stalin’s victory over his rivals in the battle for the leadership of the Communist Party that followed Lenin’s death in January 1924. Having outmaneuvered his most formidable opponent, Trotsky, Stalin appropriated his program of rapid industrialization and vastly accelerated it. Stalin feared that boosting the wealth of the peasantry would increase its political power. To free the party and state once and forever from being held hostage, he sought to diminish the economic resources of the peasantry and ultimately transform it by collectivizing farm production. Wealth squeezed out of agriculture would finance the growth of heavy industry and, with it, an enlarged working class.

The call for very rapid industrialization was central to what historians have dubbed Stalin’s “revolution from above.” Its success was predicated on a revival of the heroic spirit and mass mobilization of the revolution and the civil war. Stalin’s “vision of modernity” embodied in the First Five-Year Plan, wrote historian Orlando Figes, “gave a fresh energy to the utopian hopes of the Bolsheviks. It mobilized a whole new generation of enthusiasts,” including young workers and party activists, for whom the industrialization drive was to be their October. By sheer willpower, the Soviet Union would seize modernity and catch up to and pass its capitalist rivals.19

The giant factory played a pivotal role in the effort. One Soviet planner said that preparing a list of needed new factories was “the soul of five-year plans.” While some funds were invested in renovating and expanding existing plants, building new ones provided the opportunity for installing the most advanced technology available. Some experts proposed adopting European methods and machine designs, their smaller scale and lesser demand for precision standardized parts as more appropriate to the existing state of Soviet industry than American mass production. But Soviet leaders decided to adopt the American model, seeing investment in a few, very large factories, where great economies of scale could be achieved through rationalization, specialization, and mechanization, as a better use of precious investment funds than spreading them thinly to build more, smaller, less technically advanced plants. When one critic of that approach questioned the availability of trained labor to operate American machinery, asking “Maybe you want to breed a new race of people,” Vassily Ivanov, the first manager of the Stalingrad tractor plant, replied “Yes! That is our program!”

The First Five-Year Plan incorporated a few big projects already begun or planned, like the Dnieporstroi dam and hydroelectric project, and proposed massive new ones, like the Magnitogorsk iron and steel complex and the several tractor and automobile factories. These landmark projects would create the transportation and power infrastructure, iron and steel industry, and tractor and vehicle output to transform the whole country and lay the basis for new defense production.

The epic scale of the First Five-Year-Plan projects reflected the utopianism associated with it and the need to stir popular imagination for the massive mobilization and sacrifice it required. Giantism was as much an ideological matter as a technical one. The very scale of the planned industrial complexes made achieving modernity, measured against the most advanced nations, and doing so quickly, seem a palpable possibility, something worth suffering to achieve. Tempo was deemed an existential issue. “We are 50–100 years behind the advanced countries,” Stalin declared in 1931. “We must make up this distance in ten years. Either we do this, or they will crush us.”20

Turning to the West

The Soviet Union lacked the engineering cadre, experience, and capital goods manufacturing capacity to build the Five-Year Plan projects on its own. Necessity forced it to turn to personnel and machinery from the capitalist world. Some foreign experts already were working in the Soviet Union, but their role greatly expanded once the First Five-Year Plan got under way. Not only did the Soviet Union have too few engineers, industrial architects, and other specialists experienced with large-scale projects; equally important, the Bolsheviks distrusted the experts they had, most of whom had begun their careers working for private firms, had not supported the revolution, and were seen as lacking knowledge of the newest industrial developments and the boldness and initiative found abroad, especially in the United States. The largest group of foreign experts the Soviets recruited came from Germany, with Britain and Switzerland also providing significant numbers of engineers and technicians. But in terms of their role, American companies and consultants were most important, taking on outsized roles in the leading Five-Year Plan projects. Though unsympathetic to the Russian Revolution, American businesses did not hesitate to take advantage of the commercial possibilities it presented.21

The influx began with work on Dnieporstroi, the huge dam and hydroelectric project in the Ukraine, the largest in Europe when it opened in 1932. In 1926, a Soviet delegation visiting the United States signed a contract with Hugh L. Cooper, who had supervised the construction of the dam and power station in Muscle Shoals, Tennessee, to play a similar role for Dnieporstroi. For one or two months a year, Cooper worked on site, while a small group of engineers from his firm stayed year-round. The Soviets purchased much of the heavy equipment for the project in the United States. The Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company built nine turbines for the dam, the largest ever manufactured, and sent engineers to supervise their installation. General Electric built some of the generators, part of its very extensive involvement in Soviet electrification and industrialization during the late 1920s and 1930s.22

American involvement in the Stalingrad tractor plant was even more extensive. The tractor held almost mythical importance in the Soviet Union; Russian-American writer Maurice Hindus, who traveled frequently in his native land, declared the tractor the “arbiter of the peasant’s destiny,” “not a mechanical monster, but a heroic conqueror.” Tractors almost never were sold to individual peasants but rather used as inducements and support for collective cultivation. The tractor station, which housed equipment for use on nearby collective farms, became a key Soviet institution, not only supplying mechanical power but also collecting grain for the state and serving as a symbol of modernity and Bolshevik power. Rebellious villages did not get access to tractors.23

Already spending heavily to import tractors, the Soviet government made their domestic production an investment priority. Having been spurned in its request to Henry Ford to set up a Russian tractor plant, the government turned to the next best thing, Ford’s favorite architect, Albert Kahn. Soviet leaders knew of Kahn because of his work at River Rouge. But in planning what would become the Stalingrad plant, they did due diligence, in November 1928 sending a delegation of engineers to the United States to study tractor production and visit equipment manufacturers and engineering and architectural firms, including Kahn’s. In early May 1929, Amtorg, a trading company controlled by the Soviet government, signed a contract with the Detroit architect to design a factory capable of producing forty thousand tractors a year (a target later raised to fifty thousand). Kahn also agreed to lay out the site, supervise the construction, help procure building materials and equipment from U.S. companies, and supply key personnel for the start-up of the plant.24

Upon signing the Amtorg contract, Kahn presented the problems the Soviet Union faced as technical, with it having many of the same challenges and opportunities as the United States. As would be true in most of his statements about the U.S.S.R., he never mentioned communism and avoided politics. Perhaps to forestall criticism from anticommunist businesses, he portrayed the Soviet Union as a large potential market for U.S. equipment manufacturers.25

In choosing the Kahn firm, Soviet leaders threw in their lot with a company capable of operating at the rapid pace at which they hoped to carry out industrialization. Within two months of signing the contract, two Kahn engineers arrived in the Soviet Union with preliminary drawings for the main buildings. John K. Calder had worked on building Gary, Indiana, and been the chief construction engineer at River Rouge, a role he essentially reprised at the Stalingrad Tractorstroi, working alongside Vassily Ivanov. Leon A. Swajian, another Rouge veteran, assisted him. Other Kahn representatives and engineering recruits soon joined them.

But if leading Bolsheviks and the Kahn firm were largely in tune about pace—if anything the Russians wanted to go faster—as Calder quickly discovered conditions on the ground were anything but conducive to rapid progress. Modern equipment for transportation and construction was all but absent—camels were used to move materials—while many Soviet construction officials objected to the fast-track methods Calder introduced. Ivanov later wrote that he had to confront “the sluggish inertia of Russian building methods” in what became a political as well as technical battle over the all-important issue of “tempo.” A popular play by Nikolai Pogodi, entitled Tempo, would portray the struggle, with a character based on Calder overcoming many obstacles, including bureaucracy and lack of discipline, to push the project forward.

Remarkably, the basic construction at Tractorstroi, which became the largest factory in the Soviet Union, with an assembly building a quarter mile long and large adjacent foundry and forge buildings, was completed in just six months, though it took another half year for all the equipment to arrive and be installed. Meanwhile, factory officials set up a recruiting office in Detroit and hired some three hundred and fifty American engineers, mechanics, and skilled workers to help start up the plant, including fifty from the Rouge, a process made easier by the beginning of the Great Depression. At the same time, young Soviet engineers were sent to collaborate with the Kahn firm on design work and to various American factories to gain experience with the kind of machinery that would be used in the plant. Ivanov himself traveled to meet with equipment suppliers in the United States, where “The straight roads, the abundance of machines, the whole technical equipment . . . convinced me of the correctness of the course we had chosen.”26

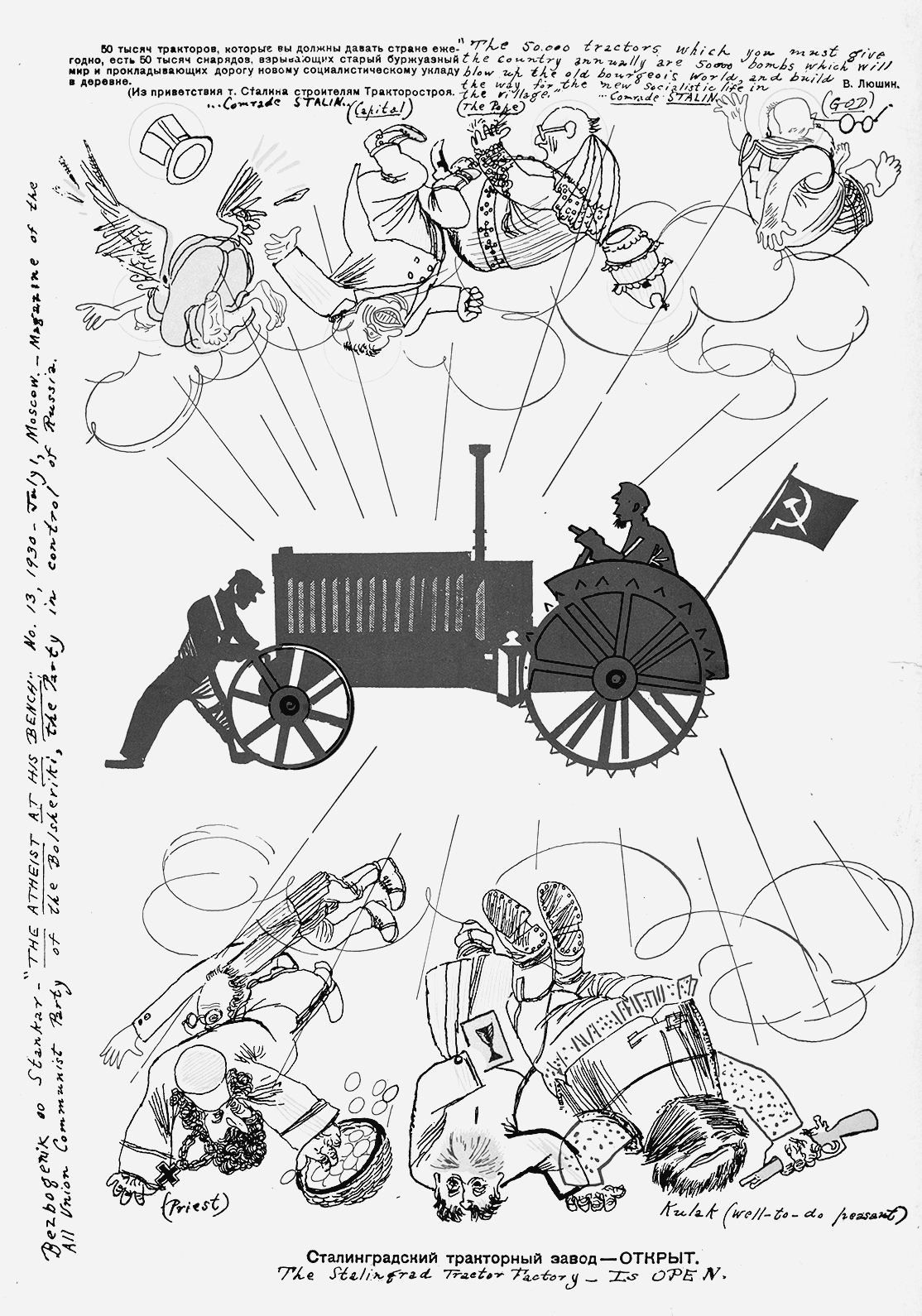

Figure 5.2 The Stalingrad Tractor Factory Is Open, the celebratory cover of a 1930 issue of a Soviet magazine.

On June 17, 1930, just fourteen months after Amtorg signed its contract with Kahn, tens of thousands of spectators gathered in Stalingrad to watch the first tractor, decorated with red ribbons and placards, come off the assembly line. By then, a start-up workforce of 7,200 had been assembled, 35 percent female. Stalin sent his congratulations to the workers, declaring, “The fifty thousand tractors which you are to give the country every year are fifty thousand shells blowing up the old bourgeois world and paving the way to the new socialist order in the countryside.” He ended, less bombastically, by giving “Thanks to our teachers in technique, the American specialists and technicians who have rendered help in the building of the Plant.”27

While work on the Tractorstroi was proceeding, Amtorg went on a buying spree in the United States, signing technical assistance and equipment purchase agreements with some four dozen companies. The most important agreement was with Ford. When Kahn signed his contract, Henry Ford seemed to regret not being involved in the great experiment of Soviet industrialization. Publicly, he offered Kahn help and asked him to tell the Soviets “anything we have is theirs—our designs, our work methods, our steel specifications. The more industry we create no matter where it may be in the world, the more all the people of the world will benefit.” Privately, he asked Kahn to signal to the Soviets that he was now willing to make a deal.

Nine months earlier, the Soviet government had set up a commission to build up its vehicle industry, which at the time consisted of only two small factories producing fewer than a thousand trucks a year. In the spring of 1929, the decision had been made to build a giant vehicle plant near Nizhny Novgorod, 250 miles east of Moscow. By then, the Soviets had approached both Ford and General Motors about assistance, but without much progress. Impatient, Stalin personally intervened behind the scenes, demanding that Amtorg speed up negotiations. Ford’s new interest was thus a godsend, and by the end of May Amtorg signed an agreement with his firm.

The pact did not revive the idea of Ford setting up a plant in the Soviet Union. Instead, it called for massive assistance to the Soviets in building up an automobile industry under their own aegis. In a nine-year contract, Ford agreed to help design, equip, and run a plant at Nizhny Novgorod capable of manufacturing seventy thousand trucks and thirty thousand cars a year, as well as a smaller assembly plant in Moscow. Ford granted the Soviets the right to use all of its patents and inventions and produce and sell Ford vehicles in the country. It pledged to provide detailed information about the equipment and methods used at River Rouge and to train Soviet workers and engineers at its Detroit-area plants. The agreement also called for the Soviet Union, during the period its own plants were being started up, to buy seventy-two thousand Ford cars, trucks, and equivalent parts. (The vehicles were sent as knocked-down kits to be assembled at Soviet plants.) Although Ford later claimed that it lost money on the agreement, it served both sides well, giving the U.S.S.R. a huge boost in setting up a modern car and truck industry while providing Ford with work during the depth of the Depression and allowing it to sell off the tools and dies for the Model A as it switched to its new V8 model.28

To design the Moscow assembly plant and a temporary assembly plant in Nizhny Novgorod, the Soviets again turned to Kahn. But for the main Nizhny Novgorod factory, which was to be the largest automobile plant in Europe—conceived of as a scaled-down version of the Rouge, a fully integrated, mass production facility—and for a nearby city to accommodate thirty-five thousand workers and their families, the Soviets signed a contract with the Cleveland-based Austin Company, one of the leading industrial builders in the United States, which had recently erected a huge Pontiac factory for General Motors. If Kahn’s firm was noted for its design innovations, Austin was best known for its one-stop approach, planning, building, and equipping complete industrial facilities using standardized designs and highly rationalized techniques. Though experienced with big projects, the Soviet commission was larger than anything it had ever undertaken.29

Like the Kahn engineers in Stalingrad, the first fifteen Austin engineers to arrive at Nizhny Novgorod—there would be forty at the peak—faced challenges quite unlike anything they had known. Living conditions were difficult and good food scarce. Chronic shortages of materials and labor delayed construction (though at the height of the effort forty thousand workers—40 percent female—were on the job). Water, heat, and power facilities and systems for transporting and storing equipment and supplies had to be built from scratch. The Soviets lacked the managerial experience or tools for a project of this scope. Expensive imported equipment was lost, misplaced, left outside to deteriorate, and stolen, while primitive machinery and brute force were used in its stead. Layer upon layer of bureaucracy, competition among organizations involved in the project, and constant personnel changes made decisions torturous and their implementation difficult. Cost-cutting forced last-minute design changes and the redoing of carefully worked out plans. And then there were the natural conditions, months and months of extreme cold, springtime floods, and massive fields of mud.30

Austin largely retained control over the design and engineering of the factory complex, but the Soviets ultimately took over planning the adjacent city. The urban center would be one of the first new cities built in the Soviet Union and as such became an opportunity to envision what a socialist city should look like. A design competition led to a plan that included extensive communal facilities and, in some sections, no traditional living units.

The first phase of the city had thirty four-story residential buildings. Most were divided into individual apartments housing several families each (already the urban norm in the face of a massive national housing shortage), but some buildings were designed for an experiment in social reorganization. Clusters of five of these buildings, connected by enclosed elevated walkways, were to be living and social units for a thousand persons each. Each unit had its own clubhouse with social, educational, and recreational facilities and a large communal dining room, where it was anticipated that most meals would be consumed. Showers were clustered communally and there were library, reading, chess, and telephone rooms and special spaces for the study of political matters, military science, and science experimentation (to encourage innovation and technical expertise, allowing the country to free itself of dependence on foreigners). Kindergartens and nurseries allowed parents to leave their children as long as they chose, including, essentially, full time. Living spaces were small, meant largely for sleeping, with no individual cooking facilities. The top floors of the “community units” had larger rooms designed for “communes” of three or four young people who would live, work, and study together.

The utopianism of the auto city quickly floundered in an ocean of need and the desire of construction workers and later automobile workers for individual apartments. Even before the first residential buildings were completed, they were flooded with squatters, workers who had been living in tents, dugouts, and other improvised structures through a long winter. Cots and little individual stoves appeared everywhere. Planners expected that communal living would become more popular, allowing them to convert buildings divided into traditional apartments to the community unit model, but in the end the conversions went the other way, as workers sought more private, individualized spaces. Also, cost-cutting meant that after the first buildings were completed, designs for communal facilities were reduced, and eventually the whole master plan for the city was abandoned. Still, even in its truncated form, the new workers’ city represented a particularly elaborate realization of a broader effort to provide extensive social, cultural, and recreational programs and benefits through the workplace, with factories all over the Soviet Union taking responsibility for housing and feeding their workers and their families, educating them, and uplifting their cultural level. The Soviet welfare state centered on the large factory.31

In spite of all the obstacles, the huge auto complex at Nizhny Novgorod, soon to be renamed Gorky, was essentially completed in November 1931, just eighteen months after the first American engineers arrived (though construction of the accompanying city lagged behind). Specialists from the United States and the application of American methods accounted for some of the success. But much of the credit had to go to Soviet government and party officials, who, in spite of their inexperience, bureaucratic ways, and frequent ineptitude, proved able to mobilize heroic efforts by Soviet workers. They could do so because they could capitalize on a reservoir of deep commitment by at least some workers, particularly young ones, to crash development—industrialization as a form of revolution. Engaged in what they understood as a world-historic project and defense of the revolution, Soviet workers made extraordinary sacrifices, living in miserable circumstances, volunteering to work unpaid Saturdays, joining “shock brigades,” accepting dangerous worksite conditions, and putting up with the bumbling and arrogance of officials in charge of the big Five-Year Plan projects. For at least a brief moment, many Soviet workers saw the factories they were building as theirs, as the means to a brighter future, to a different kind of society, and were willing to do whatever was necessary to complete them.32

The Kahn Brothers in Moscow

The Stalingrad tractor plant and the Gorky automobile factory were among the best-known Soviet projects in the West, receiving extensive coverage in the American press. The New York Times, Detroit Times, Detroit Free Press, Time, trade journals, and other publications regularly ran stories about them.33 But there were many other large Soviet projects with Americans involved, too. Du Pont helped set up fertilizer factories, Seiberling Rubber Company assisted in constructing a large tire factory, C. F. Seabrook built roads in Moscow, other companies advised on coal mines, and the list went on and on.34

Albert Kahn took on an expanded role after work on the Tractorstroi started. In early 1930, his firm signed a two-year contract with Amtorg that made it the consulting architect for all industrial construction in the Soviet Union. Under the agreement, twenty-five Soviet engineers worked with the firm in its Detroit offices. But more importantly, it established a Kahn firm outpost in Moscow within a newly created, centralized Soviet design and construction agency. Albert’s younger brother Moritz led a team of twenty-five American architects and engineers in the new Russian office, not only designing buildings but also teaching Soviet architects, engineers, and specialists the methods of the Kahn firm.

The contract with the Soviet Union provided a boon for Kahn, enabling his firm to survive through the trough of the Great Depression, when virtually no new construction took place in the United States. But more than just expediency, the Soviet-Kahn partnership grew organically from a shared vision of progress through physical construction and rationalized methods. Moritz relished the opportunity to apply the “standardized mass production” system of the automobile industry to construction—a notoriously chaotic industry making custom products—which would be possible in the U.S.S.R. because there would be one centralized design agency and one customer, the Soviet government, allowing the development of designs for particular types of factories that could be used over and over. Moritz pointed out that government ownership would eliminate the costs associated with advertising, sales promotion, and middlemen and allow the rationalization of transportation and warehousing, all of which appealed to his technocratic sensibility. Albert was more patronizing; he told the Detroit Times, “My attitude toward Russia is that of a doctor toward his patient.”35

The joint Moscow design center proved challenging but ultimately successful. There were few qualified Soviet architects, engineers, or draftsmen available when it began and a lack of basic supplies, from pencils to drafting boards, with only one blueprint machine in all of Moscow. Nonetheless, in two years the Kahn team supervised the design and construction of over five hundred factories across the Soviet Union, using the Fordist methods the firm had perfected in Detroit. Equally important, some four thousand Soviet architects, engineers, and draftsmen were trained by the Kahn experts, including in formal classes taught in the evenings. They, in turn, took the approach to design and construction developed by Kahn, in collaboration with Ford and other U.S. manufacturing firms, and spread it throughout the country. Kahn’s methods, according to Sonia Melnikova-Raich, who chronicled his Soviet collaboration, “became standard in the Soviet building industry for many decades.”36

Kahn also did more Soviet design work in his Detroit office, including two new tractor plants to meet the insatiable demand for mechanized agricultural equipment. A plant in the Ukraine, on the outskirts of Kharkov, was virtually a copy of the Stalingrad plant, designed to produce the same model tractor and varying only in the greater use of reinforced concrete, as the Soviets diminished their expensive steel imports from the United States. Leon Swajian, after finishing up as number two at the Stalingrad plant, served as general superintendent for the construction (receiving the Order of Lenin for his role). The other plant was the biggest yet. Located in Chelyabinsk, some 1,100 miles due east of Moscow, just east of the Urals near the border between Europe and Asia, it was designed to produce tractors with metal crawlers rather than wheels. The buildings in the complex, looking like a chunk of Detroit industry planted in the Russian wilds, had a combined floor area of 1,780,000 square feet, laid out on a tract of 2,471 acres (twice as large as the Rouge). Though the Soviets began building the plant without American advisors on site, when things got bogged down, American engineers, including Calder and Swajian, were called in to help.37

Starting Up

If building the gigant Soviet factories had been an enormous challenge, getting them to actually produce goods proved even more difficult. Their start-up became a moment of truth for the idea that the Soviet Union could leapfrog into modernity by adopting the most advanced capitalist methods on a giant scale, building a socialist society without going through an extended process of industrialization like the United States and the Western European powers had experienced.

The Stalingrad Tractorstroi was the first test. Stalin’s June 1930 message congratulating the tractor-factory workers on beginning production of fifty thousand tractors a year proved wildly premature. During the first month and a half, the factory produced only five tractors. During its first six months, only just over a thousand. During all of 1931, 18,410.

Not all the equipment had arrived and been installed when the plant opened. But the bigger problem was the utter unfamiliarity of the vast bulk of the workers and Russian supervisors with basic industrial processes, let alone advanced mass production. When Margaret Bourke-White visited the factory during its first summer of operation, she reported, “the Russians have no more idea how to use the conveyor than a group of school children.” In the plant, “the production line usually stands perfectly still. Half-way down the factory is a partly completed tractor. One Russian is screwing in a tiny bolt and twenty other Russians are standing around him watching, talking it over, smoking cigarettes, arguing.”38

The American workers, engineers, and supervisors hired to help start up production and teach the workforce necessary skills had their hands full. Henry Ford’s dictum, that mass production could occur only if parts were so standardized that no custom fitting was required, immediately proved a trial. The skilled Russian workers the plant did have largely had been trained in craft ways. Plant manager Vassily Ivanov raced around the factory in a rage when he saw foremen using files to fit together parts (probably because some parts were not truly interchangeable, a problem at Highland Park as late as 1918). As usual in the Stalinist universe, the metaphor of war was used to describe the situation: “We were fighting our first battle,” Ivanov later said, “against handicraft ‘Asiatic’ methods,” making the traditional Marxist equation of Asia with backwardness and Europe with modernity.

Unskilled workers posed, if anything, a greater problem. Many had just arrived from small peasant villages, never having seen a telephone, let alone a precision machine tool. Frank Honey, an American toolmaker, described the first worker sent to him to train as a spring maker as “a typical peasant . . . dressed as he was in some strange, countrified sort of clothes.” Such workers did not have any notion of basic factory procedures. Bearings in expensive new machines were quickly damaged because they did not know to keep oil free of dirt. Discipline was often lax, with a great deal of standing around doing nothing. It required a slow, painstaking process to teach the new workforce, which swelled to fifteen thousand, how to operate the sophisticated machinery, especially as the American instructors had to work through translators.

Furthermore, the Soviet Union lacked the well-developed supply chains on which Fordism rested. High-speed machine tools required steel of precise specifications, but when the tractor factory could get the raw materials and supplies it needed at all (which was often not the case), the composition and quality varied from batch to batch, making for spoiled parts, damaged tools, and long delays.

Fordism also required complex coordination, which the plant management had no experience in achieving. Workers and managers spent endless time in consultations and meetings, but nonetheless things did not arrive where and when they were expected. When Sergo Orjonikidje, the Commissar for Heavy Industry, in charge of implementing the Five-Year industrialization plan, visited the factory as political pressure mounted to get production going, he reported, “What I see here is not tempo but fuss.”

With Stalin personally monitoring daily production figures—a measure of how important the plant was seen to the future of the country—personnel changes came quickly. Ivanov was replaced by a more technically knowledgeable communist official to work alongside a new top engineering specialist. The Soviet Automobile Trust sent yet another American engineer to the plant, an expert on assembly-line production, to try to straighten out the mess. To help establish order, the plant cut back from three daily shifts to just one.

Slowly, production began to improve, though product quality remained a problem. Much of the advance came from the growing experience of the workforce and skills gained though a massive training and education effort. The peasant newcomer whom Honey schooled eventually became a skilled worker and later foreman of the spring department. (Rapid promotions for such workers, though, created more problems, as their replacements needed to be trained.) During the first six months of 1933, the plant turned out 15,837 tractors, a significant improvement, but, after three years of operation, still well below the projected annual production of “fifty thousand shells blowing up the old bourgeois world.”39

At the Nizhny Novgorod auto plant, managers tried to avoid the start-up problems encountered at Stalingrad. They sent hundreds of workers to Detroit to learn production techniques at Ford, while recruiting hundreds of Americans to come help get the plant going. (The presence of a female Soviet metallurgist studying heat treatment at Ford merited a headline in the New York Times, part of an unending fascination among American reporters and engineers with Soviet women holding blue-collar jobs that in the United States were strictly male.) Production was begun gradually, first just assembling car and truck part kits sent from Detroit before beginning to make all the needed parts on site. Still, the plant took longer than expected to get up to speed.40

Again, shortages of supplies and managerial ineptitude were part of the problem, but a shortage of labor, especially skilled labor, would have made a rapid start-up impossible under the best conditions. Larger than the Stalingrad Tractorstroi, what was soon named GAZ (Gorkovsky Avtomobilny Zavod [“Gorky Automobile Factory”]) had thirty-two thousand workers. Few had any industrial experience or much work experience of any kind. When the plant opened, 60 percent of the workers were under age twenty-three and only 20 percent over age thirty. Nearly a quarter of the manual workers were female. It was almost like being in an early British or American textile mill, in a world of the young.

New workers and their foreign teachers confronted difficult conditions. Living quarters were primitive, if somewhat better for the Americans, and meat, fish, fresh fruit, and vegetables nearly impossible to find. When Victor and Walter Reuther, auto union activists from Detroit, arrived at the plant in late 1933 to work as tool- and die-makers, most of the complex had no heat. They were forced to perform and teach precision metalworking in temperatures far below freezing, periodically going into the heat-treatment room to warm their hands.

As at Stalingrad, political pressure quickly mounted to get production going. Even before the plant opened, ineptitude became criminalized; nine officials were tried for “willful neglect and suppression” of suggestions made by American workers and technical specialists. After a show trial in Moscow before several thousand spectators, light sentences—at most the loss of two months’ pay—were handed out, in a warning to other managers. Three months after production began, Orjonikidje came to inspect, accompanied by Lazar Kaganovich, like him a member of the Politburo, the top communist ruling body. The pair blamed local communists and unionists for mismanagement and slandering engineering and technical personnel, resulting in the firing of some plant and regional party officials.

But slowly production improved, a measure of the eagerness of the young workforce to learn new skills and what amounted to a whole new way of life and their resilience in the face of hardship. By the time the Reuther brothers headed back to the United States after eighteen months at GAZ, most of the other foreign workers already had departed, the skill level of the native workforce had enormously improved, more food and consumer goods were available, and cars and trucks were steadily coming off the line. New York Times Moscow reporter Walter Duranty, a big booster of Stalinist industrialization, in declaring his confidence that GAZ would quickly get up to speed, chided that “Foreign critics sometimes fail to realize two things about Russia today—the astonishing capacity for bursts of energy to get the seeming impossible accomplished and the fact that Russians learn fast.” When two Austin engineers returned to the plant site in 1939, they were “dumbfounded” to see that a city of 120,000 people had grown up around the core residential area they had constructed, with six- to eight-story apartment buildings, paved streets, “quite a few flowers,” and people who “looked better.”41

As a cadre of skilled workers developed, other start-ups became easier. When the Kharkov tractor plant began operations in the fall of 1931, it benefited from a large group of experienced workers who were transferred from its twin in Stalingrad. Also, rather than immediately having to manufacture the 715 custom parts that went into its tractors, the plant could begin assembling vehicles using some parts shipped over from the Stalingrad factory.42

By contrast, the construction and initial operation of the Magnitogorsk Metallurgical Complex made the Stalingrad tractor factory and the Gorky automobile plant look like easy sailing.43 Before the revolution, Russia had only a small iron and steel industry. The First Five-Year Plan called for a huge leap in metal production. Key to the effort was to be a massive integrated steel plant forty miles east of the Urals, next to two hills which contained so much iron ore that they affected the behavior of compasses, giving them the name Magnetic Mountain (Magnitnaia gora) and the city that was to arise with the plant the name Magnitogorsk. By some accounts, Stalin personally called for the creation of the complex after learning about the U.S. Steel plant in Gary, Indiana. Like Gary, the plant was to include every phase of the production of steel products, including blast furnaces, open-hearth converters, rolling mills and other finishing plants, coke-making furnaces, and equipment to make chemicals out of coke by-products. Unlike Gary, the complex included its own iron mine.

Magnitogorsk—“The Mighty Giant of the Five Year Plan,” as one Soviet periodical dubbed it—was but one component of an even larger scheme, a Kombinat, an assemblage of functionally and geographically related facilities, which stretched all the way to Kuznetsk in Central Siberia, the source of most of the coal initially used in the steel complex, and which included the Chelyabinsk tractor factory, 120 miles northwest of Magnitogorsk. Even some of the less-heralded Kombinat factories were huge, like the railroad car plant in Nizhny Tagil, north of Chelyabinsk. A prominent part of the Second Five-Year Plan, which began in 1933, the sprawling factory complex employed forty thousand workers and had its own blast furnaces and open-hearth department.44

Foreign experts helped design Magnitogorsk, but unlike in Stalingrad and Nizhny Novgorod no one firm coordinated the whole effort, creating myriad problems. In 1927 the Soviets retained the Freyn Engineering Company of Chicago as a general advisor in developing its metallurgy industry, and it did some initial planning for Magnitogorsk. Then the Soviets hired the Cleveland firm of Arthur G. McKee & Company to do the overall design, but amid much rancor the company proved unable to churn out plans at the rate the Soviets desired. So its role was cut back and other U.S. and German firms were brought in to design particular components of the complex, with various Soviet agencies playing a part, too. As a result, in the words of American John Scott, who spent five years working at Magnitogorsk, its elements were “often very badly coordinated.” The whole project was late in getting going and took far longer to complete than originally projected.

Even if the planning had been better managed, the scope of work and the challenges of the site would have made the “super-American tempo” the Soviets claimed was being maintained impossible to achieve. When work at Magnitogorsk began, there was nothing in place, no buildings, no paved roads, no railroad, no electricity, insufficient water, no coal or trees to provide heat or energy, no nearby sources of food, no cities within striking distance. Out of the dust of the steppe, Soviet officials and foreign experts had to conjure up a vast industrial enterprise, and do so in the cruel weather east of the Urals, where summers were short and winters exceedingly long and cold. In January and February, the low temperature averaged below zero degrees Fahrenheit. Some winter mornings it was thirty-five degrees below zero. John Scott, while working as a welder on blast furnace construction, once came upon a riveter who had frozen to death on the scaffolding.45

Much like the first English textile factory owners, Magnitogorsk managers had to recruit a workforce to build and operate the complex, which by 1938 had twenty-seven thousand employees, and come up with ways to house it, feed it, and take care of all its needs in an isolated spot where there never had been a large assemblage of people. Some workers came voluntarily, swept up in enthusiasm for the effort to leap forward to modernity and socialism or simply looking for an escape from their village or an unpleasant situation. Others were assigned by their employers to go to Magnitogorsk, like it or not. But such workers were not enough, especially since they flowed out of Magnitogorsk almost as quickly as they flowed in, put off by the extremely primitive living conditions and difficult work. So, again, like the early English mill owners, the Soviets turned to unfree labor, on a huge scale.

The Soviets used forced labor at many big projects, including the Chelyabinsk tractor factory, the Dnieprostroi Dam, and, most famously, the White Sea–Baltic Canal, constructed almost entirely by prisoners. At Magnitogorsk, by Scott’s account, in the mid-1930s some fifty thousand workers were under the control of the security police, the GPU (after 1934, the NKVD), most doing unskilled construction work but some employed in the steel plant itself. Even more than the early English textile mills, Magnitogorsk refuted simple correlations between industrialization, modernity, and freedom.

Forced laborers in Magnitogorsk fell into several categories. Common criminals made up the largest group, over twenty thousand workers, most serving relatively short sentences, living in settlements (including one for minors) surrounded by barbed wire, going to work under guard. A second group consisted of peasants dispossessed during the collectivization drive, so-called kulaks, deported to the steel city. In October 1931, there were over fourteen thousand former kulak workers and twice that number of their family members living in “special labor settlements,” initially enclosed by barbed wire, too. Even by Magnitogorsk standards, conditions for the forced migrants were appalling, with 775 children dying in one three-month period. (By 1936, most restrictions on these workers were eased.) Finally, there were veteran engineers and technical experts, trained under the old regime, who had been convicted of crimes but nonetheless worked as specialists and supervisors, in some cases, especially in the early days, holding very responsible positions, generally indistinguishable from other managerial personnel except for their legal status.46

The use of prison labor constituted just one part of the intertwining of the national security apparatus with the crash industrialization. In Magnitogorsk, as construction and production delays and difficulties stretched on and on, the NKVD became ever more involved with the steel complex, a shadow force with more power than the factory administration and the local government and, at some points, even than the local Communist Party. Problems stemming from poor planning, incompetent management, untrained workers, supply and transportation shortages, and the wear on machines and workers from politically driven crash efforts were increasingly attributed to failure to follow the Communist Party line, to deliberate wrecking and sabotage, and eventually to conspiracies involving foreign powers and internal oppositionists, like the “Trotskyite-Zinovievite Center” and the “Polish Military Organization,” which were alleged to be operating in Magnitogorsk. Starting in 1936, all industrial accidents became subjects of criminal investigations. “Often they tried the wrong people,” Scott commented, “but in Russia this is relatively unimportant. The main thing was that the technicians and workers alike began to appreciate and correctly evaluate human life.”

But if technicians and workers developed a greater appreciation of human life, the police and judiciary became ever more cavalier in their treatment of workers and managers, as arrests, interrogations involving “physical measures,” fabricated evidence, detentions, and executions became common. Top factory managers, state officials, and party functionaries toppled into the abyss as real and perceived failures were attributed to treachery and counterrevolution, until finally even the leaders of the Magnitogorsk NKVD, who led the terror, themselves fell to it. Though no exact count is available, according to Scott, in 1937 the purge led to “thousands” of arrests in Magnitogorsk. And it was similar elsewhere; at the Gorky auto plant, during the first six months of 1938, 407 specialists were arrested, including almost all the Soviet engineers who had spent time in Detroit and some of the few Americans who still remained at the factory.47

Watching on the ground, Scott saw the fury of charges, countercharges, and arrests impede production, but in his view only temporarily and to a limited extent. Overall, as managers and workers slowly mastered their jobs, supply and transportation problems were ironed out, and new components of the complex came on line, Magnitogorsk’s output of iron ore, pig iron, steel ingots, and rolled steel all moved upward, as did productivity.48 Some of the gigants built during the 1930s never reached their projected output, but, overall, the First Five-Year Plan (which was accelerated to be finished in four years) and the Second Five-Year Plan that followed led to an enormous leap in Soviet industrial output. Estimates vary, but between 1928 and 1940 total industrial output increased at least three-and-a-half-fold and by some accounts as much as sixfold. The greatest gains were in heavy industry. Iron and steel production more than quadrupled. Machine production increased elevenfold between 1928 and 1937, and military production twenty-five-fold. By the latter year, motor vehicle production approached two hundred thousand vehicles. Electrical power increased sevenfold. Transportation and construction also swelled. By contrast, output of consumer goods—a low priority in the First Five-Year Plan—rose only slightly. Stalin was premature in 1929 when he said, “We are becoming a country of metal, a country of automobiles, a country of tractors,” but a decade later there was much truth to his claim.49

Making Socialist Citizens

The giant Soviet factories were conceived of not only as a way to industrialize and protect the country but also as instruments of culturalization, which would create men and women capable of operating these behemoths and building socialism. Communist leaders often described this cultural project as fighting backwardness—the illiteracy, ignorance of modern medicine and hygiene, and unfamiliarity with science and technology that characterized the bulk of the population of the prerevolutionary Russian Empire. Many Bolsheviks, especially Lenin, defined culture in traditional European terms, as literacy, knowledge of science, appreciation of the arts. Civilization meant novels, chess, Beethoven, indoor plumbing, electricity. But some communists, and to some extent the party and state as a whole, at least through the early 1930s, believed that a distinctly communist culture and civilization should be created out of the revolution. The factory was an instrument to realize socialist modernity.50

The simple act of coming to a factory could launch the process of cultural change. This was especially the case for men and women from peasant villages, and even more so for migrants from nomadic regions of the country. Many newcomers had never seen a locomotive, indoor plumbing, electric lights, even a staircase. Walking into a factory for the first time could be terrifying, just as it had been in earlier years in England and the United States. A. M. Sirotina, a young woman who came to the Stalingrad tractor factory from a village near the Caspian, remembered, “There was an awful roaring and hammering of machines and there were motor-cars whizzing to and fro over the shop. I dodged to one side in fright and took refuge behind a stand.”51

That a young woman was on the shop floor of the Tractorstroi reflected the profound change in gender roles and family relations that accompanied the gearing up of heavy industry. After the revolution, the Communist Party and the Soviet government promoted women’s equality and new familial arrangements, but the changes were especially dramatic in the budding industrial centers, where there was no old order that had to be overthrown. At the start of the First Five-Year Plan, 29 percent of industrial workers were female; by 1937, 42 percent. Women held many types of positions for which they would never even be considered in the United States or Western Europe, such as crane and mill operator. Still, old ways died hard, as some men refused to allow their wives to work, abused them, and abandoned their families without alimony or child support.52

Learning utterly unfamiliar jobs took time. To hasten the process, the Soviets launched a massive educational effort. In addition to informal shop-floor training by skilled workers, supervisors, and foreign experts, formal classes were held after work to teach skills for specific jobs. Victor Reuther recalled that the Gorky auto plant “was like one huge trade school.” Rollo Ward, the American foreman of the gear-cutting department at the Stalingrad tractor plant, noted that while in the United States factory owners tried to keep workers from fully understanding the machinery they operated, in the Soviet Union workers were encouraged to learn everything about the equipment, beyond just what was needed to perform their own particular tasks.53