Chapter 16

There are days when you get up and smell death in the air, and that Good Friday was one of them. It was a grey, close morning, with ugly clouds that bore the promise of storm, and waking to the memory of the evening’s horrors drove my spirits to the cellar. I told the others what I’d seen, and it struck them silent until one of ’em, I forget who, dropped to his knees and began to intone the Lord’s Prayer. They thought it was all up with them, and when Theodore came on the scene in a raging temper, and ordered everyone back to Magdala, except me, Prideaux shook my hand in what he plainly thought was a last farewell. I didn’t; my guess was that Theodore was keeping his word to put them in a safe place, and you may be sure I demanded to go with them, but he wouldn’t hear of it.

“You are a soldier!” cries he. “You shall be my witness that if blood is shed, it shall not be my wish! I have word that your army is across the Bechelo and advancing against me. Well, we shall see! We shall see!”

Rassam pleaded with him to send a message to Napier, but he vowed that he’d do no such thing. “You want me to write to that man, but I refuse to talk with a man sent by a woman!”

Which was a new one, if you like, but sure enough when a letter arrived from Napier for Rassam, Theodore wouldn’t listen to it and swore that if Rassam wrote to Napier that would be an end of their friendship. So off they went to Magdala, but Rassam slipped the letter to me, begging me to persuade Theodore to look at it. He was no fool, Rassam, for he and the others were barely out of sight when Theodore bade me give the note to Samuel, who read it to him. It was a straight courteous request for the release of the prisoners, and for a long minute I hoped against hope as he stood frowning in thought, but then he lifted his head and I saw the mad glare in his eye.

“It is no use! I know what I have to do!” He turned on me. “Did I not spend the night in prayer, and do I not know that the die is cast?” Since he’d spent most of the night getting blind blotto, and thereafter roaring for his whore, I doubted if his decision had been guided by prayer, much; I think the effect of his massacre was still at work in him, but I’m no mind-reader. All that mattered was that the last chance of a peaceful issue had gone, and it behoved all good men to look after Number One, and bolt at the first chance.

It never came. He kept me with him all day, and since he was never without his bodyguards, to say nothing of servants, and his generals coming and going, I could only wait and watch with my hopes diminishing; plainly the grip was coming, and the question was, when he went down to inevitable bloody defeat, would he take his prisoners with him? Fear said yes; common sense said no, what would be the point? But with a madman, who could tell?

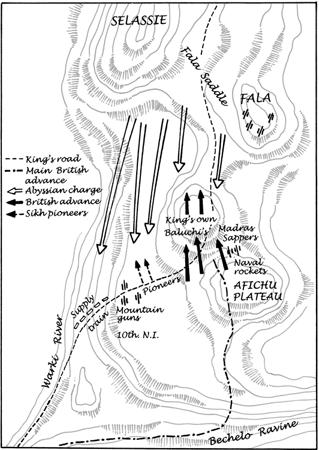

There was a terrific thunder-plump at about noon, and then the sky cleared for a while and the heat came off the ground in waves; it was breathless, stifling, and even when the cloud thickened and rain began to fall in big drops, it brought no coolness with it. Five miles away, although I didn’t know it, Napier’s battalions were fording the muddy Bechelo barefoot, and climbing out of that mighty ravine in sweltering heat, short of water because the river wasn’t fit to drink, breasting the long spur that brought them to the Afichu plateau that I’d marked on Fasil’s sand-table, and coming near exhausted to the edge of the Arogee plain. That was the main column; the second force came up the King’s Road, which I’d warned Napier to avoid – and he almost paid dear for ignoring my advice.

Runners brought word to Theodore of our army’s approach, and from early afternoon the Ab army, seven thousand strong, was moving into position from the Islamgee plain to the lower slopes of Fala and Selassie. Theodore himself, with his generals and attendants and your reluctant correspondent, went up the muddy slope to the gun emplacements on the Fala summit, and looking back I had my first proper sight of what Napier would be up against: rank upon rank of robed black spearmen and swordsmen and musketeers swinging along in fine style, disciplined and damned business-like with waving banners and their red-robed commanders, five hundred strong on horseback, marshalling them to perfection. I didn’t know what force in guns and infantry Napier might have, but I guessed it wouldn’t be above two thousand, and I was right; odds of three to one, but that wouldn’t count against British and Indian troops … unless something went wrong, which it dam’ nearly did.

From the Fala summit we got our first sight of the approaching columns, almost three miles away across the great expanse of rock and scrub, on the far side of Arogee. Theodore was like a kid in a toyshop with his glass, turning to me bright with excitement and bidding me look and tell him who was who and what they were about. It had begun to rain in earnest now, with lightning flashing in the black clouds and a strong wind sweeping across the summit, but the light was good, Theodore’s glass was a first-class piece, and when I brought it to bear I almost dropped it in surprise, for the first thing I saw was Napier in person.

There was no mistaking him, for like old Paddy Gough he affected a white coat, and there he was, a tiny figure sitting on his pony on a knoll about two miles away with his staff about him, and not a thing between him and us except some Bombay and Madras Sappers skirmishing ahead of his position. No place for a general to be, and it was with some alarm that I traversed the glass and got an even greater shock, for I could see that the bughunting old duffer was courting catastrophe all unaware – and I wasn’t the only one who’d noticed.

His own position, with the first column still some distance behind him, was dangerous enough, but over to the right, coming up the King’s Road, was the second column, and it was led by a convoy of mules, barely escorted, with supply train written all over ’em – rations, ammunition, equipment, the whole quartermaster’s store of the brigade simply begging for some enterprising plunderer to swoop down on them … and here he was, at Theodore’s elbow, leaping with excitement at the heaven-sent chance.

He was old Gabrie, the Ab field-marshal, who’d come thundering up from the Fala saddle where he’d been supervising his army’s assembly, flinging himself from his horse and bawling:

“See, see, Toowodros, they are in our hands!” He was an old pal of Theodore’s, all ceremony forgotten. “Let us go, in God’s name! We have them, we have them!”

If Theodore had been as smart a soldier as Gabrie … well, we might have had a disaster to rank with Isandhlwana or Maiwand, but he hesitated, thank God, and lost the chance. And since it all happened with such speed, so many different factors together, I’d better take time to explain.

The march up the spur and the Afichu plateau to Arogee had taken longer than expected, thanks to the broiling heat, the steepness of the climb, and the fact that they didn’t think they were marching to battle, but merely to sites to pitch camp. Napier wasn’t expecting an Ab attack, and got too far forward (in my opinion), and the baggage column had easier going on the King’s Road and likewise arrived too quickly in an exposed position. Phayre got the blame, justly or not I can’t say. If Theodore had allowed Gabrie to attack at once, the baggage column was done for, and that might have spelled disaster; I say might because Napier was a complete hand when it came to improvising, as he was about to show.

Well, Theodore hesitated to cast the dice, with Gabrie pleading to be let loose. Not long, perhaps, but I reckon long enough, before he cried, “Go, then!” Gabrie was off like a shot, waving his scarf to advance the army, and Theodore yelled to the gunners to fire. The German workmen had been measuring the charges, but the Ab gunners manned the pieces, and the first salvo almost caught Napier himself, a chain-shot landing a few yards behind him. And by then he’d had another nasty start, as the whole crest from Fala to Selassie suddenly came to life with seven thousand Ab infantry rolling down to Arogee like a black-and-white tide, bellowing their war-songs and bidding fair to sweep away the Sappers screening Napier’s knoll, who had only muzzle-loading Brown Bess to stem the flood. And to the right the baggage column, caught in the open and barely guarded, must be engulfed by the savage legions bearing down on it.

I thanked God in that moment that I was watching that charge from behind, and not from in front of it, for it must have been a sight to freeze the blood, those great robed figures racing down in a chanting mass almost a mile from wing to wing, sickle-swords and spears flourished, black shields to the fore, braids and robes flying, and out in front old Gabrie, sabre aloft, his brilliant red silk cloak billowing behind him, the five hundred scarlet-clad cavalry chieftains at his back. From above it looked like the discharge from an overturned ant-hill spilling across the plain towards an enemy caught unprepared by the sheer speed of the attack.

That was when Bob Napier earned his peerage. He had a couple of minutes’ grace, and in that time he had the King’s Own, who’d been hurrying towards the sound of the guns, skirmishing past him to join the Sapper screen, and in behind the khaki figures I saw the dark puggarees of the Baluch. As they deployed, waiting for the onslaught, Napier opened up with the Naval Brigade rocket batteries which he’d called up to a point just behind his knoll. In a moment the white trails of smoke were criss-crossing the plain, the rockets smashing into the Ab ranks, cutting furrows through them; they wavered and checked, appalled at this terrible new weapon they’d never seen before, but then they came on again full tilt through the pouring rain, the King’s Own stood fast, and on the word three hundred Sniders let fly in a devastating volley that blew the red-coated horsemen’s charge to pieces and staggered the infantry mass behind them.

Why they didn’t run then and there, I can’t fathom. The rockets must have been terror enough, but now they were meeting rapid-fire breech-loaders for the first time, yet still they came on until the Sniders and the Enfields of the Baluch stopped them in their tracks, and they gave back, firing their double-barrelled muskets as they went and being shot down as they tried to find cover among the rocks and scrub oaks. The King’s Own advanced steadily, a horseman who I guess was their colonel keeping them in hand; still the Abs retreated and died … but they never ran, and I guess my time there must have made me an old Abyssinian hand, for I find myself writing “Bayete, Habesh!” on their behalf. There, it’s written. In their shoes I’d not ha’ stopped running till Magdala.

While this was happening, Theodore was pounding away with his Fala battery, which I realised was unlikely to damage anyone (the chain-shot that almost did for Napier must have been a great fluke), but on the right the baggage of the second brigade was in mortal peril. The right wing of the Ab charge was thundering down on it, the spearmen singing like Welshmen, careless of the shells bursting above them from the guns of the Mountain Train formed up on the King’s Road ahead of the baggage. Our guns were flanked by the Punjabi Pioneers, burly Sikhs in brown puggarees and white breeches, and as the Abs came surging up the slope to their position, letting fly their spears, they were met by two shattering volleys – and then the Sikhs were charging them with the bayonet against Ab spears and swords, smashing into their ranks like a steel fist, outnumbered but forcing the robed tribesmen back, and standing by Theodore on Fala I had to clamp my jaws tight to stop myself yelling, for I remembered their fathers and uncles at Sobraon, you see, and within I was crying: “Khalsa-ji! Sat-sree-akal!” There’s no hand-to-hand fighter in the world better than a Sikh with his bayonet fixed; they scattered the spearmen like chaff and charged on, and I saw the fancy red puggarees of the 10th Native Infantry among them as they pitchforked the enemy into the gullies – those same ravines that I’d marked on Fasil’s table as a death-trap if we’d blundered into them.

There were more Abs trying to outflank the baggage convoy, but the Sikhs and Native Infantry shot them down among the rocks, and the few King’s Own who acted as baggage guards stood off those who got within striking distance. But this part of the action was too far for me to see, and events on Fala were claiming my attention.

Theodore’s half-dozen cannon had been belching away to no good purpose, partly because his Ab gunners were incompetent, partly because the German loaders, I suspect, were making sure that the charges were all wrong. Why chain-shot was being used, I couldn’t figure, because it’s a naval missile, but that’s Theodore’s army for you: lions for bravery but bloody eccentric. But even if his gunners had been Royal Artillery they’d have had the deuce of a job, for firing dropping shot from a height is a dam’ fine art.

So is building, loading, and firing mortars. Theodore’s pet toy, Sevastopol, may have been the biggest piece of ordnance in the history of warfare for all I know, but the German artisans who cast it, never having made a gun before, botched it either accidental or a-purpose, for at its first discharge it blew up with an explosion you could have heard in Poona. I suspect it was deliberate mischief 47 from the fact that there wasn’t a squarehead in sight when it was fired, and only the Ab gunners felt the full force of the blast which killed three or four and wounded as many more; it nearly did for Theodore himself, but fortunately for him there was an unwitting guardian angel on hand to save him.

I see it plain even today: the gunners climbing on the mortar housing, the rabble of attendants and staff watching from a respectful distance, the gunners at the other pieces holding their fire, the rain squalls sweeping across the muddy plateau, Theodore on his mule with his umbrella at the high port … and I had just turned to take a towel from a servant to wipe the water streaming down my face, when a tremendous rushing thunder seemed to burst out of the ground itself, the very earth shook, and bodies, debris, and gallons of mud were flying everywhere. I wasn’t five yards away, but by one of those freaks for which there’s no accounting the blast passed me by; I didn’t even stagger, and was thus in a position to move nimbly as seventy tons of solid iron, jarred loose from its housing by that colossal explosion, toppled ponderously in my direction.

Which was capital luck for his Abyssinian majesty, thrown by his startled mule and landing slap in my path as I dived for safety. Ask any man who’s been hit foursquare by a fleeing Flashy, fourteen stone of terrified bone and muscle, and he’ll agree that it’s a moving experience; Theodore went flying, brolly and all, and I landed on top of him while the enormous mortar, belching smoke, rocked to a standstill on the very spot where he’d been trying to keep his balance.

His words as we scrambled, mud-soaked, to our feet, were most interesting. “You saved me!” he yelled, and then added: “Why?” Some questions are impossible to answer: “I beg your pardon, I didn’t mean to,” would have been true but inappropriate, but I suppose I made some sort of noise for he stared at me, looking pretty wild, and then turned to the ruin of his mortar, gave a strange wail and clasped his head in his hands, and sank to his knees in the puddles. Unlike mine, his emotions were not shuddering terror at our escape, nor was he overwhelmed by gratitude. I suppose the fact was that Sevastopol had cost him a deal of labour, dragging it half across Ethiopia, and here he was literally hoist with his own petard. And serve the selfish bastard right.

His grief for his useless lump of iron was quickly cut short as a Congreve rushed past overhead, and another absolutely struck one of the cannon, spraying fire and shrapnel everywhere and mortally wounding the Ab gun-captain. The Naval gunners had found our range, and several more rockets hissed above us, weaving crazily, for they were no more reliable than they’d been years before when I’d fired them at the Ruski powder ships under Fort Raim. One came a sight too close for comfort, though, scudding between the guns and killing a horse. For the first time I saw Theodore scared, and he wasn’t a man who frightened easy. He clasped his shield before him and shouted: “What weapons are these? Who can stand against such terrible things?” But it didn’t occur to him to leave the summit, although presently he bade the gunners cease fire. “They do not fear my shot!” cries he, and began to weep, pacing about the summit and finally taking station on the forward edge to stare stricken at the final retreat of his army.

For it was as good as over now, a bare hour and a half after he’d started the fight with his first gun. The plain was thick with dead and dying Abs, the defeated remnant scrambling back over the rocky slopes of Fala and Selassie, turning here and there to fire their futile smooth-bores and scream defiance at the King’s Own and Baluch advancing without haste, picking their targets and reloading without breaking stride. The sun was dipping behind the watery clouds, and then it broke through as the rain died away, sending its beams across the battlefield, and a splendid rainbow appeared far away beyond the Bechelo. It was damned eerie, that strange golden twilight, with the rocket trails fizzing their uncertain way over the field to explode on the Fala saddle, and the muffled crack of the Mountain Battery’s steel guns, the red blink of their discharges more evident as the dusk gathered over Arogee.

Messengers had been galloping up since the onset, mostly just to hurrah at first, but now came the news that old Gabrie had gone down, and presently it became clear that most of those scarlet-clad cavalry chiefs had fallen with him. Theodore threw his shama over his head, crying bitterly, and sat down against a gun-carriage. Now he wouldn’t look down at the carnage below, or at the wreck of his army stumbling wearily back over the Fala saddle to Islamgee, but at last he dismissed the gun-teams, keeping Samuel and myself and his pages with him. When darkness fell, Ab rescue parties ventured out with torches to find their wounded, whose wails made a dreary chorus in the dark, and Speedy told me later that when our stretcher-bearers, whom Napier had sent out to bring enemy wounded to our field hospital, had encountered Ab searchers in the dark, they’d worked together without a thought. Our medicos patched up quite a few of Theodore’s people, which, as Speedy observed, made you realise how downright foolish war can be.

But then, ’twasn’t really a war, nor Arogee a proper battle. Like Little Big Horn, it was more of a nasty skirmish, and like Big Horn it had an importance far beyond its size.

On the face of it, there wasn’t much for the Gazette. No dead on our side, although I believe a couple of our thirty wounded died later, and only seven hundred Abs killed – I say only, you understand because when you’ve seen Pickett’s charge and the Sutlej awash with thousands of corpses, Arogee’s a fleabite (provided you ain’t one of the seven hundred, that is). For our fellows, it had been a day’s shooting, but for the Abs it was Waterloo. They’d been shot flat, massacred if you like, by Messrs Snider and Enfield, gallant savages decimated by modern weapons … but for once the liberals can’t sniff piously over that, for even at close quarters, steel against steel, Ab swords and spears had been no match for Sikh bayonets. For the Abs, it was shameful disaster, and for Theodore it was finis.48

For our side, it was something unheard of, a victory without loss at the end of a campaign that had been supposed to end in catastrophe. But Speedy told me there was no joy in our camp, only pity and admiration for a foe who hadn’t been good enough, and a perverse irritation that it hadn’t been worth all the toil and effort. T. Atkins and J. Sepoy had expected a real battle, an Inkerman or Balaclava, a Mudki or Ferozeshah, against a foe they could touch their hats to. Arogee had been a sell; the Abs had been no opposition at all – oh, they’d tried, and been a mighty disappointment.

That, I can assure you, is what my countrymen felt. Victory had been so easy that they felt cheated. D’you wonder that I shake my head over ’em?49

It was well after dark before Theodore could rustle up the will to bestir himself. He sat for a good two hours like a man stunned, not seeming to hear the cries of the wounded below Fala, or that sudden ghastly scream which told us that the jackals and hyenas were at work. At last he summoned Samuel and dictated a letter to Rassam asking him to make his peace with Napier. I can give it exact, for Samuel gave me a copy later, as evidence that he’d done his bit to bring about an armistice. It was a real Theodore effusion:

My dear friend, how have you passed the day? Thank God, I am well. I, being a king, could not allow people to come and fight me without attacking them first. I have done so and my troops have been beaten. I thought your people were women but I find they are men. They fought very bravely. Seeing that I am not able to withstand them, I must ask you to reconcile me to them.

He gave it to a couple of the Germans to take to Magdala, and then we went down to Islamgee, through a torch-lit purgatory of dead who’d been brought up from the battlefield, and wounded being cared for by their comrades. It was raining again, and the guttering flares shone on rows of shrouded corpses, and on lean-tos and tents where the Ab surgeons were at work. Under one long canopy were laid the scarlet-clad bodies of some of the five hundred chiefs who had led the charge and been peppered by the King’s Own and Baluch, who’d supposed that one of ’em must be Theodore.

He stood silent a while, looking at them, and then moved slowly along the line, stopping now and then to touch a hand, or lay his own on a forehead, before turning away. Someone called his attention to another body in a tent nearby, and when they drew back the shroud who should it be but Miriam, looking pale and beautiful and very small. It took me aback; I’d forgotten her in the tumult of the last few days, and seeing her lifeless gave me a shock that I find hard to describe. I mean, I bar vicious bitches who are prepared to burn me to death by inches, but she’d been a lovely peach and I’d have dearly liked to explain the Kama Sutra to her by demonstration. So I can’t say I was grief-stricken, or even moved, much, just sorry as one is to see a beautiful ornament broken, and irritated by the waste.

Some of her mates were around her, keening what I guess was a death-song, and I asked the ugly little trot I’d christened Gorilla Jane how it had happened. Miriam hadn’t been in the battle, but watching with the others from the Fala saddle, and a screaming fire-devil had exploded by her: a rocket. The others had escaped injury, so I guess bonny little Miriam was the only female casualty of Arogee. Well, at least I gave her a moment’s thought, which was more than Theodore did; he spared her not so much as a glance as he strode on to his tent. Gratitude of princes, what?

You’d ha’ thought, would you not, that it was now all over at last? His army had been thrashed out of sight, he’d confessed with bitter tears that there was no resisting such weapons, and he’d asked Rassam to make peace for him. He changed his mind in the course of the night, which he spent getting raging drunk, and vowing that he’d be damned before he’d sue to Napier, but by dawn he was seeing reason again (for the time being) and I was treated to the sight of Prideaux, in full fig, limping down from Magdala to get his marching orders from the Emperor: he, and one of the German prisoners, a preacher named Flad, were to go with one of Theodore’s sons-in-law, a nervous weed named Alamee, to open negotiations with Napier.

His majesty was in his sunniest mood by now, inquiring after Prideaux’s health, pressing drink on him, and complimenting him on his appearance – at which I couldn’t help smiling approval, for our jaunty subaltern was putting on dog in no uncertain manner. His old red coat was sponged and pressed, his whiskers shone with pomade, his cap was on three hairs, his cane under his arm, and his monocle in his eye. Rule Britannia, thinks I, and stamped my heel in reply to the barra salaama he threw me as he and his companions rode down to Napier’s head-quarters beyond Arogee. Theodore watched their progress through his glass from the summit of Selassie, and was much gratified when one of his scouts panted up to report that the party had been received with cheering and hats in the air.

If he thought that this natural rejoicing at seeing two of the prisoners free at last was a happy omen, he was brought back to earth when they returned in the afternoon with Napier’s reply. By then his mood had changed for the worse, thanks to his chiefs, who came to the Selassie summit en masse to point out that he still had nine-tenths of his army in good fettle, and if they fell on Napier by night, when artillery and rockets would be useless, they could make him sorry he’d ever crossed the Bechelo. Whether Theodore believed this or not, he was looking damned surly by the time Prideaux and Flad and Alamee returned to inform him that Napier’s terms amounted to unconditional surrender, with the prisoners freed and Theodore willing to “submit to the Queen of England”, with a promise that he’d be given honourable treatment.

Reasonable enough, considering the trouble and expense we’d been at, and the barbarous way he’d behaved, wouldn’t you say? But you ain’t the descendant of Solomon and Sheba, with notions of imperial grandeur, unable even to contemplate submitting your sacred person to the representative of a mere woman who’d added injury to insult by ignoring your letter and then invading your country. Just to show you how far he was from understanding us, his first question was: did honourable treatment mean we’d assist him against his enemies, and would we look after his family – wives, concubines, numerous offspring, etc?

Flad, who interpreted, put this to Prideaux, who said, being an honest English lad from a good home, that we’d do the decent thing, goodness me. Flad was explaining this in diplomatic terms when Alamee, who’d been hopping nervously as Theodore’s scowl grew blacker, seized his majesty’s arm and drew him out of earshot, chattering twenty to the dozen.

“Talkin’ sense into him, I hope,” says Prideaux to me. “Is the feller changin’ his mind? His army don’t look like surrenderin’, I must say!” Nor did they, ranged in their silent thousands on the lower slopes of Selassie beneath us, and on Fala across the way. “Never saw so many glowerin’ faces! Well, he’d better swallow the terms, ’cos they’re the best he’ll get – what, after the way he’s carried on, keepin’ us chained for two years, torturin’ poor old Cameron, butcherin’ his own folk right and left! The man’s a blasted Attila! And if he expects Napier to just say, ‘So long, old fellow!’ and pack his traps, he’s sadly mistaken!”

“He’s mad, remember,” I told him – and what happened next bore me out, for Theodore began to rage and stamp as Alamee pleaded with him. “Please, Father, there is no hope!” he was crying. “The choice is surrender or death! The English dedjaz swears that if a hair of the Europeans’ heads is touched, he will tarry here five years if need be to punish the murderers – his words, Father, not mine!”

“Be silent, imbecile!” bawls Theodore, and there and then sat himself down on a rock and dictated a reply to Napier at the top of his voice, while we and his chiefs and minions listened in disbelief. For you never heard such stuff, starting off with a Theodoric rant about the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, and then a great harangue – not addressed to Napier, but to the people of Abyssinia, and how they’d fled before the enemy, and turned their backs on him, and hated him, after the way he’d fed their multitudes, the maidens protected and unprotected, the women made widows at Arogee, and aged parents without children … amazing babble, while he glared up at the heavens and his admiring court exclaimed in awe.

“He’s slipped his cable,” mutters Prideaux. “God help us!”

But now Theodore seemed to remember to whom he was writing, for he complained that Napier had prevailed by military discipline, the implication being that it wasn’t fair “and my followers who loved me were frightened by one bullet, and fled in spite of my commands. When you defeated them, I was not with the fugitives. Believing myself to be a great lord, I gave you battle, but by reason of the worthlessness of my artillery, all my pains were as nought …”

You may think I’m exaggerating, that no one could blather such nonsense, but it’s there in the Blue Books, and I heard it up yonder on Selassie, how his ungrateful people had taunted him by saying he’d turned Muslim, which wasn’t true, and he had intended with God’s help to conquer the whole world, and die if he couldn’t fulfil his purpose, and he’d hoped after subduing Abyssinia to lead his army against Jerusalem and expel the Turks. And if it had been dark at Arogee he’d have licked us properly. Not since the day of his birth had anyone dared lay a hand on him, and finally, a warrior who had dandled strong men like infants would never submit to be dandled by others.

So there. When he’d done dictating, he had the scribe read it over to him, which gave Prideaux the chance to tell me that Napier sent his compliments and congratulations, the Gallas had the southern approaches sealed, and he’d despatched another agent to Masteeat to see that my good work was continued.

“Sir Robert was quite bowled over at first to hear that you had fallen into Theodore’s hands, and Captain Speedy – what a remarkable chap he is! – wondered if you hadn’t allowed yourself to be taken on purpose.” Prideaux was regarding me with that look of wary respect that my heroic reputation invariably excites in the young. “Sir Robert said why ever should you do any such thing, and Captain Speedy said it might be all for the best, because if it came to a point, you would know what to do. Sir Robert asked what did he mean, but Captain Speedy made no reply.” Prideaux coughed and fixed me with an earnest eye. “I tell you this, Sir Harry, because after a moment’s reflection Sir Robert told me to give you his order that whatever befell, you were to remain with the Emperor Theodore and use your best judgment.” He coughed again. “I’m not sure what he meant, sir, precisely, but I’m sure you do.”

I knew all right, as the Gates of Fate clanged to behind me. Whatever befell, I was to use my best judgment to ensure that the Emperor of Abyssinia didn’t leave Magdala alive.

a Big salute.