I still say that if it hadn’t been for that damned gag, I’d have been back on the Far West before midnight, rogering her speechless. And she knew it, too, and must have arranged for my abductors to muzzle me first go off, so that I’d never get a word in edgeways to sweetheart her. You see, however much they loathe you, whatever you’ve done, the old spark never quite dies – why, for all her hate, she’d blubbered at the mere recollection of our youthful passion, and for all she said, our weeks on the boat could only have reminded her of what she’d been missing. No, she knew damned well that if once she listened to my blandishments she’d be rolling over with her paws in the air, so like old Queen Bess with the much-maligned Essex chap, she daren’t take the risk. Pity, but there it was.

But I confess these speculations weren’t in my mind just then, as they dragged me through the dark woods, hammering me when I stumbled, and thrust me astride a pony. Then it was off up a gentle slope, with those four monsters round me; I was near suffocating with the gag, which didn’t assist thought as I tried to grapple with the impossibility of what had happened.

Yet I knew it wasn’t impossible. Mrs Candy was Cleonie, come back like Nemesis; once the patch was off, and she’d whispered that snatch of her French riding song, in her old voice, I’d have known her beyond doubt. I couldn’t marvel at not recognising her earlier, even at the closest quarters; she’d grown, for one thing, filled out admirably, and the brash, hard Mrs Candy was as different from the dove-like Creole as could be, in speech and manner – aye, and nature. I suppose that’s what twenty-five years of being bulled by redskins and whoring on the frontier and acquiring bordellos does to you. Not surprising, really. Even so, she’d played it brilliantly, hadn’t she just? Keeping me at arm’s length, the Bismarck nonsense, galloping me westward to the very spot where she could deal me out poetic justice, the spiteful bitch. What simpler than to send word to her Sioux friends (doubtless with a handsome fee) and have them scout the boat along the Yellowstone, ready at her signal to pounce on the unsuspecting victim and shanghai him into the hills to stick burning splinters in his tenderer parts? Neat, but not gaudy – simplicity itself compared to some of the plots that have been hatched all over me by the likes of Lola and Lincoln and Otto Bismarck and Ignatieff and … God, I’ve had some rotten luck.

What I couldn’t fathom, though, was how the devil she’d discovered that the much-respected Flashy of ’76 was the long-lost B. M. Comber of ’49. She’d heard, she said – but from whom? Who was there still who’d known me as Comber in the earlies, had recognized me now, and tipped her the wink? Spotted Tail – why, he’d never heard the name Comber in his life; I’d been Wind Breaker to him from ’50, and what should he and Mrs Candy know of each other? Susie, Maxwell, Wootton and the like I could dismiss; I hadn’t seen them or they me in quarter of a century, supposing they were still alive. Carson was dead; no one in the Army knew about Comber. Lincoln was dead. But I was a fool to be thinking of folk I remembered – there must be hundreds I’d forgotten who might still remember me, and seeing Flashy promenading down Broadway would exclaim “Comber, bigod!” Old Navy men, perhaps a returned emigrant from the wagon train, a Cincinnati invalid, someone out west, like a Laramie hunter or trader. Susie’s whores, by thunder! They’d know me, and if Cleonie was anything to go by, the graduates of Mrs Willinck’s academy might be running half the knocking-shops in America by now – aye, and corresponding with the other old girls, devil a doubt … “Dearest Cleonie, you’ll never guess who called in for a rattle at our shop the other day! ’Twas such a start! Tall, English, distinguished, fine whiskers … give up?” How many of the bawdy-houses I’d frequented had black madames? Difficult … but that would be it, like as not.

These were random thoughts, you understand, floating up through stupefied terror from time to time. The point was that four damnably hostile Sioux were bearing me into the wilderness with murderous intent, and if there was one thing I’d learned in a lifetime of hellish fixes, it was the need to thrust panic aside and keep cool if there was to be the slimmest chance of winning clear.

Once we had skirted the high bluff and reached the rough upland, they headed south-west by the stars. It might be they’d go a safe distance and then set to roasting me over a slow fire, but I doubted it; they were riding steady, so it looked like a longish trek across the northern Powder country towards the Big Horn Mountains; that was where the Sioux were mostly hanging their hats these days. Somewhere far off to my left, up the Rosebud, Custer would be starting his long swing south and west to roughly the same destination. I was pinning no hopes on him, though – the last man you want riding to the rescue is G.A.C., for there’ll be blood on the carpet for certain, and the more I thought, the more my hope grew of emerging from this pickle peaceful-like. After all, Mrs Candy wasn’t the only one with chums among the Sioux – I spoke the lingo, I could cite Spotted Tail as a bosom pal, and even if he was far away there must be hostiles who’d remember me from Camp Robinson and who might think twice about dismembering a U.S. treaty commissioner just to please the former squaw of Broken-Moon-Goes-Alone. Certainly they’d not be well disposed to anyone white just now, and given a prisoner they’re more likely to take a long thoughtful look at his innards than not. But again, I might buy my way clear, or get a chance to play my real trump card – somewhere up ahead, and the nearest thing to God between Canada and the Platte, was Tashunka Witko Crazy Horse, and while I hadn’t seen him since he was six, he wouldn’t let them snip pieces off a man who’d practically dandled him on his knee, surely?

I put these points to my captors at our dawn halt, when they had to remove my gag to let me drink and eat some jerked meat and corn-mush; I suggested that the cleverest thing they could do would be to return me to the fire-canoe on the Yellowstone, where I’d see they got safe-conduct and all the dollars they wanted from Many-Stars-Soldier Terry.

They listened in ominous silence, four grim blanketed figures with the paint smeared and faded on their ugly faces, and not a flicker of expression except pure malice. Then their leader, one Jacket, started to lambast me with his quirt, and the others joined in with sticks and feet, thrashing me until I yelled for mercy, and didn’t get it. When they were tired, and I was black and blue, Jacket stuffed the gag back brutally, kicked me again for luck, and stooped over me, his evil grinning face next to mine.

“You have two tongues – you are not American, although you sat with the liars at White River. You are the Washechuska Wind Breaker, who sold my brother’s woman, Walking Willow, to the Navajo who shamed her. You are going to die – kakeshya!b” He launched into a description that can give me nightmares even now, and took another hack at me. “Spotted Tail! A woman and a coward! We’ll send him a gift of your –, since he seems to have lost his own!”

The others howled with glee at that, and threw me on to the pony with more blows and taunts. And now I knew real fear, as I realised that I was tasting the temper of the hostile Sioux, the merciless desperate savages who stood beyond the law, who were not going to be rounded up on to the agencies, who loathed everything white and despised Spotted Tail as a traitor, and who were preparing, with all the hate and fury Custer could have wished, to meet whatever the Americans might send against them. One white captive wasn’t going to buy or bully his way out of their clutches; torturing him to death would be a momentary amusement on the way to better things.

All day we rode south-west over the bare country east of the Big Horn; even allowing for my jaundiced eye, it was neither a grand nor memorable prospect, just endless low hills and ridges of yellow grass, with a few trees here and there, and the outline of mountains far in the distance. A few vivid pictures stay in mind: a buffalo skeleton picked clean in a gully, a hawk that lingered above us for hours in the blazing afternoon, a party of Sans Arc Sioux who crossed our trail and yelled exultant news of a great victory over the Grey Fox Crook to the south – not a word of Custer, though, which seemed odd, for he must be well up the Rosebud by now. Then on, over those endless sparse hollows and hills, with the grasses blowing in the wind, while my body ached with ill-usage and weariness, and my unaccustomed backside must have rivalled the setting sun. My thoughts – well, I don’t care to dwell on them; I remembered the fate of Gallantin’s scalp-hunters, and Sonsee-array laughing merrily over the details.

We lay that night in a gully, and every joint in my ageing body was on fire when we rode on next morning. Ahead of us there were bluffs now, and in the gullies we met occasional parties of Indians, hunters and women with burdens, and a few boys running half-naked in the bright sunshine, playing with their bows, their voices piping in the clear air. I caught a glimpse of a river down below us to the left, and presently we reached the top of the bluffs, my guards were whooping and calling to each other in delight, and as my pony jolted to a halt I raised my tired head and saw such a sight as no white man had ever seen in the New World. I was the first, and only a few saw it later, and most of them didn’t see it for long.

Directly below us the placid river wound in great loops between fine groves of trees in a broad valley bottom. On our side the valley was enclosed by the bluffs on which we stood, although to our right the bluffs became a ridge, running away for a couple of miles into the hazy distance. From the bluffs to the river the ground fell pretty steeply, but from the crest of the long ridge the slope was much more gentle, a few hundred yards of hillside down to the river with a few gullies and dry courses here and there. It’s like any other hillside, very peaceful and quite pretty, all clothed in pale yellow grass like thin short wheat, with a few bright flowers and thistles. All ordinary enough, but I suppose there are a few old Indians who think of it now as others may think of Waterloo or Hastings or Bannockburn. They call it the Greasy Grass.

But I barely noticed it that morning, for on the opposite bank of the river was a spectacle to stop the breath. Anyone from my time has seen Indian villages – a few score lodges, sometimes a few hundred perhaps covering the space of a cricket field. But here in splendid panorama was a town of tipis that must have covered close on ten square miles; as far as I could see the bank was a forest of lodges, set in great tribal circles from the thick woods upstream to our left to the more open land farther down opposite the Greasy Grass slope, and from the groves by the water’s edge back to a low table-land in the distance, where a great pony herd grazed.

It was the largest assembly of Red Indians in history,71 and while I couldn’t know that, I was sufficiently awestruck – were these the few dispersed bands of hostiles I’d heard lightly spoken of, the fag-end of the once-mighty Sioux confederacy which Terry and Gibbon had been afraid might melt away and escape; the thousand or two who weren’t worth bringing up the Gatlings for? I saw Custer’s face turned in impatience to Lonesome Charley Reynolds: “We are more than a match for them if they were all together.” Well, they were all together with a vengeance; there must be ten thousand of the red buggers down there if there was one – who the devil could they all be? I didn’t know, but all America knows now: Hunkpapa, Sans Arc, Brulé, Oglala, Minneconju, the whole great roll-call of the Dacotah nation, with Arapaho, Blackfeet, Stony, Shoshoni and other lesser detachments from half the tribes of the North Plains and Shining Mountains – and not forgetting my old acquaintances, the Cheyenne. Never forget the Cheyenne. But five or ten thousand, Charley, it made no difference – everyone knew they weren’t going to fight. Not they – not Sitting Bull or Crazy Horse or Two Moon or Brave Bear or Lame White Man or Bobtail Horse or White Bull or Calf or Roan Horse or a few thousand others. Especially not the ugly little gentleman whom I’d put up for membership of the United Service Club if I had my way, since he was the best soldier who ever wore paint and feathers, damn him. His name was Gall.

Well, there they were, all nice and quiet in the morning sun, with the smoke haze hanging over the vast expanse of tipis, and the women and kids down at the water’s edge, washing or playing, but I didn’t have long to look at it, for Jacket led us on to a ravine that ran down from the bluffs opposite the centre of the great camp; only later did I learn that it’s called Medicine Tail Coulee, and that the river, which is hardly deep enough to drown in and half a stone’s throw across, was the Little Bighorn.

The ford from the coulee to the camp was only a few inches of water above a stony bed; we splashed over and under the cotton-woods on the far bank, where women and children came running to see, but Jacket pushed ahead to the first line of tipis beyond a flat open space where fires burned and dogs prowled among the litter, and we dismounted before a big lodge with a few braves lounging outside. The stink of Indian and woodsmoke was strong inside as well as out; Jacket thrust me into the dim interior and cut my wrist cords, but only so that he could tie my numbed hands to the ends of a short wooden yoke which his pals laid across my shoulders. He thrust me down into the rubbish on the tipi floor and shouted, and a girl came in.

“This one,” growls Jacket, “is a dirty lump of white buffalo dung who is to die by inches when the One-Who-Catches has seen him. Has he come yet?”

“No, Jacket,” says the girl. “He was in the south, where the fighting was with the Grey Fox seven days ago. Perhaps he will come soon.”

“Until he does, this one must speak to nobody. Take the gag from his mouth now and give him such scraps as the dogs have left. If he speaks,” says he, glaring at me, “I will cut off his lips.” And he drew his knife and threw it point first into the earth beside my foot. His pals crowed, and beyond them I could see curious faces peeping through the tipi flap, come to see the interesting foreigner, no doubt.

The girl fetched a bowl of water and a platter of corn and meat, knelt by me, and removed the gag from my burning mouth. But for two or three short intervals, it had been there for the best part of thirty-six hours, and I couldn’t have spoken if my life depended on it; I gulped the water greedily as she put the bowl to my lips, and when Jacket growled to stop she went on pouring without so much as a glance at him, until I’d sucked the last drop dry. As she spooned the food into me I took a look at her, and noted dully that she was pretty enough for an Indian, with a wide mouth and tip-tilted nose which suggested that some Frog voyageur had wintered among the Sioux fifteen years back. She was very deft and dainty in her spooning, and Jacket got quite impatient, pushing her aside before I was finished and shoving the gag back as roughly as he knew how. He bound it in place with a rawhide strip and soaked the knot, the vicious swine, just to make sure no one could untie it.

“Keep him that way till I come again,” says he, and kicked me two or three times before swaggering out with his pals, leaving me in a state of collapse on the scabby buffalo rug against the tipi side. The girl collected her dishes and went out, without telling me to ring if I wanted anything.

I was in despair – and rage at my own stupidity. In my folly, I had destroyed my best chance, by pitching my tale prematurely to Jacket, offering him bribes, urging acquaintance with Crazy Horse, and so on. I couldn’t have done worse, for Jacket, either out of brotherly affection for Cleonie, or for what she’d paid him, wanted me dead and damned, and was going to make good and sure that I had no second chance of stating my case to less partial Sioux who might have been disposed to listen. I was to be kept gagged and helpless until this mysterious person whom Jacket had mentioned – who was it, the One-Who-Catches? – came to have a look at me, and then presumably I’d be toted out to be strung up and played with for the amusement of the populace, none of whom would know who I was, or care, for that matter. God, that implacable bitch Cleonie-Candy had done for me with a vengeance – she and her stinking relatives.

I lay palpitating in the dim lodge, wondering if when next they fed me I’d get a chance to yell for help – and what good it might do if I did – and what were the chances of Terry and Gibbon’s little army arriving, and what might happen then. This camp, after all, was their target, if they could find it – but they must, for their scouts would see its smoke ten miles away, and there was bound to be a parley, for neither side could take the risk of precipitate attack. And if they parleyed … I felt my hopes rise. When had Gibbon figured to come up with the hostiles? The twenty-sixth … I forced my numb mind to calculate the days since we’d left Rosebud – this must be the twenty-fourth! If I could stay alive for forty-eight hours, and Gibbon’s column got here, and I could get my mouth open to some half-friendly ear …

The tipi flap parted, and the girl came in again. She glanced at me, and then began pottering with some utensils in a corner. I scrambled to my feet, with that damned yoke galling my neck, and as she looked round I ducked my head in the direction of the water-pitcher and tried to look appealing. She glanced towards the flap, and then back at me; I can’t say she looked sympathetic, for her face was strained and tired and her eyes empty, but after a moment she motioned me to sit down again, filled a bowl with water, and with some difficulty slipped free the rawhide strap that held the gag. She eased it out, and I gasped and sucked at that blessed water, easing the pain of my parched lips and tongue. I wished to God I looked more presentable, for now I saw she was decidedly comely, with her boyish figure in its dark green tunic, her slim hands and ankles, and that saucy little face that seemed so woebegone; given a shave and a comb and a change of linen I could have cheered her up in no time, but seeing my eyes on her she made a little sign for silence, glancing again towards the entrance. I spoke quietly; it came out in a croaking whisper.

“What’s your name, kind girl with the pretty face?”

She gasped in surprise at hearing Sioux. “Walking Blanket Woman,” says she, her eyes wide.

“Oglala?” She nodded. “You know the Chief Tashunka Witko?” Again she nodded, and I could have kissed her as my spirits soared. “Listen, quickly. I am the Washechuska Wind Breaker, friend of your chief’s uncle, Sintay Galeska of the Burned Thighs. This evil man Jacket intends to kill me, although I am a friend to your people—”

“Washechuska, what is that?” says she. “You are an Isantanka bad man, one of our enemies—”

“No, no! My tongue’s straight! Go to your chief, quickly—”

“Your tongue is double!” I was startled at her fierceness, and the flash of sudden anger in her eyes. “You have done great wrong – Jacket told me! All Isantanka white men are our enemies!” And before I knew it she had stuffed the gag back into my potato trap, and was hauling the rawhide up into place, while I tried to jerk my head free. But she was strong for all her daintiness, and cursed me something fearful, with little sobs among the swear-words.

“I was a fool to pity you!” She gave the strip a final tug and then clouted me over the ear. She knelt in front of me, her little face grim as she choked back her tears. “Seven days ago your Isanhonska Long Knives killed my brother in the Grey Fox fight! That is the kind of friends your people are! I was a fool to give you water and let you open your snake’s mouth! Why should I be sorry for you!” And, damme, she clocked me again and flounced away, clattering her pots and wiping her eyes.

Of all the infernal luck. Womanly sympathy one minute, and the next she was battering me because her ass of a brother had got himself killed against Crook. I struggled with my yoke and scrabbled my feet in what I hoped was a coaxing, reasonable way, but she never gave me another look, and presently went out again.

Well, that was another hope dashed – temporarily. If I was patient, her natural kindness might revive, brother or no; my powers of persuasion with the female sex are considerable, and even with my scrubby chin and dishevelled locks and tattered clobber – the remains of full evening dress, God help us, in a Sioux tipi – I knew I could charm this little looker, if she’d only listen. Ain’t it odd? Twice in as many days I’d been prevented by speechlessness from exercising my arts on unfriendly females. It never rains but it pours.

I thought I’d get another chance when they fed me again – but they didn’t. Jacket looked in once for a kick at me, but no suggestion of dinner, and I lay there miserably as evening came, and outside the drumming and chanting began – they were holding a scalp dance for the Rosebud fight, I believe, but I was barely conscious of the din, for despite the cramping agony of my yoke, and my other aches, I fell into an uneasy doze, half-filled with horrid pictures of one-eyed women and painted faces and captives bound to burning stakes who looked uncommon like me in Hussar uniform. A Saturday night it was, too.

It was bird-song that woke me, and sunlight through the tipi flap catching the corner of my eye, which was drowsily pleasant for a moment, until a harsh voice jarred me back to my plight. There were half a dozen Indians in the tipi, looking down at me with stony indifference; the one who was talking was Jacket, and he seemed to be exhibiting me.

“… when the One-Who-Catches has seen him, he will go to the fire. It is the wish of my brother’s wife, and mine, and our family’s!” He spoke as though challenging contradiction, but he didn’t get any. “Whoever he says he is, he deserves to die by kakeshya. Who says he is a friend of Spotted Tail’s, anyway?”

“Who cares?” says another, a burly ruffian with his belly hanging over his waistband and shoulders like an ox. His face was huge and ugly, but not without a humour that I was in no state to appreciate. His leggings and jacket were red, and he carried a short war-bonnet in his hand. “Do what you like with him; he’s white,” says this callous brute. “Come on! Totanka Yotanka is back from the hill; he has been ‘seeing’.” He gave a grunting laugh. “Pity he can’t ‘see’ some buffalo.”

If I’d known then that the speaker was Gall, the Hunkpapa chief I mentioned earlier, I might have been impressed, but probably not, for there was only one of the half-dozen who claimed attention. He alone had no war-bonnet or feathers, or anything but a coloured shirt; he was young and wiry, lean-faced and lank-haired and without paint – but with those eyes he didn’t need any. For a moment I wondered if he was blind, or in a trance, for he gazed straight ahead unseeing; I doubted if he even knew where he was. His shirt was blue-sleeved and gold-collared, with a great yellow band on which was a red disc, and its sleeves and shoulders were fringed with more scalps than I’d care to count. When Jacket tapped his arm, he turned those staring blank eyes on me,72 but without any change of expression: it made my skin crawl, and I was glad when they trooped out, Jacket taking another kick at me on the way – he liked kicking me, no error.

I got no breakfast that morning, either. Possibly on Jacket’s instructions, possibly because she was still peeved at me, Walking Blanket Woman didn’t look near for several hours, by which time I could hear all the bustle and stir of the great camp – voices and laughter and kids yelling and a bone-flute playing and dogs barking, and the smell of kettles, and me famished. Even when she arrived she was decidedly cool and wouldn’t remove my gag; it was only by piteous eye-rolling and head-ducking that I got her to relent sufficiently to pour water over my gagged mouth, so that I could obtain some refreshment. She raised no objection when I humped my yoke over to the flap, and took a cautious peep at the outside world.

It must have been just after noon of Sunday, June 25th, 1876. I wondered if Elspeth was in church at Philadelphia, examining the hats and pretending attentive approval of the sermon. I could have wept at the thought, and how my foolish whore-mongering had brought me to this awful pass. God, what an idiot I’d been – and that bitch Candy would be bedding one of the stokers on the Far West, no doubt. Fine subjects for Sabbath meditation, you see – but they don’t matter; what I did and saw that afternoon are what matter, and I’ll relate it as clearly and truthfully as I can.

All was calm in that part of the village between my tipi and the river. There was a fairish crowd of Indians doing what Indians usually do – squatting and loafing, scratching and gossiping in groups, some of the bucks painting, the women cooking at the fires, the kids scampering. There was a slow general drift upstream – that, I’m told, is where Sitting Bull’s camp circle of Hunkpapa was, with the other tribal groups strung out downstream, ending with the Cheyenne at the bottom limit, out of sight to my left as I peeped towards the river. Where exactly my tipi was I’ve never quite determined; all sorts of maps have been drawn of that camp, and I believe I must have been in a lodge of the Sans Arc circle, close by the river – but Walking Blanket Woman was an Oglala, so God knows. Certainly the ford was to my right front, perhaps a hundred yards off, and above the trees I had a fair view of Medicine Tail Coulee running up into the bluffs on the far shore.

Walking Blanket Woman spoke suddenly at my elbow. “Take a good look, white-face,” says she, pretty sullen. “Soon they will be looking at you. The One-Who-Catches will come today, and you will be burned. Maybe other white snakes will be burned, too, if they come any closer.”

And off she went, clattering her pots, leaving me to wonder what the devil she meant. Had Terry’s force been sighted, perhaps? If Gibbon had force-marched, he could be here today. Custer and his blasted 7th must be roaming off in the blue somewhere, or he’d have been here already. If only I could ask questions!

The hawk stoops, but in the grass

The rabbit does not lift his head.

He runs but does not see. The hunter

Waits, and the quarry is unaware.

They come, they come! from the rising sun.

Will any meet them, the hunter with his bow and long lance?

It was an old man singing in a high, keening wail, as he shuffled by, face upturned and eyes closed, dirty white hair hanging over his blanket. He had a pot from which he dabbed vermilion on his cheeks in spots as he sang; then from a medicine bag he shook dust on the ground either side. The people fell silent, watching him; even the kids stopped their row.

Who are the braves with high hearts?

Who sings? Who sings his death-song?

Is it the young hunter, shading his eyes as he looks to the east?

But the sun is high now; it shines on both the hawk and the quarry.

The thin voice died away, and a great stillness seemed to have fallen on the camp. I ain’t being fanciful; it was like the silence after the last hymn in church. Out in the heat haze they were standing in silent groups – women, children, braves in their blankets or breech-clouts, some with their faces half-painted; they were looking upstream through the trees, but at nothing that I could see. Over the river the bluffs were empty, except for a few children playing on the Greasy Grass slope to the left; the woods around us were quiet, and no birds sang now. A dog yelped in the distance, a few ponies under the care of a stripling snuffled and stamped, the crackle of a fire fifty yards away was audible, and the soft murmur of the Little Bighorn meandering through its fringe of cottonwoods. I’ll never forget that silence, as though a storm were coming, yet the sky was clear midsummer blue, with the least fleecy drift of high clouds.

Somewhere on the right, away towards the Hunkpapa circle, there was a soft mutter of sound, a rustle as of distant voices growing, and then a shout, and then more shouting, and the low throb of a drum. People began to move up that way, the braves first, the women more slowly, calling their children to them; voices were raised in question now, feet moved more quickly, stirring the dust. The hum of distant voices was a clamour, rippling down towards us as the word passed, indistinct but of growing urgency; crouched under my yoke just inside the tipi, I wondered what on earth it could be; Walking Blanket Woman pushed past me – and then from the trees up to the right there was a scatter of people, and I heard the yell:

“Pony-soldiers! Long Knives coming. Run, run quickly! Pony-soldiers!”

In a moment it was chaos. They ran like startled ants, braves shouting, women screaming, children rolling underfoot, all in utter disorder, while the yells from upstream increased, and then came the distant crack of a shot, and then a fusilade, and then the running rattle of irregular firing, and to my disbelieving ears, the faint note of a bugle, sounding the charge! At this the panic redoubled, they milled everywhere, with some of the braves yelling to try to restore order, and the mob of women and children surging past downstream. The men were trying to herd them away, and at the same time shouting to each other, and with mothers crying for their children and vice versa, and the wiser heads trying to give directions, it was bedlam. The crash of distant firing was continuous now, and to my right I could hear the whoops and war-cries of men running to join the fight, wherever it was.

One thing was sure – it wasn’t Gibbon. If he came at all it would be from my left, downstream; this was all up at the southern end of the valley, and they were pony-soldiers. Christ, it could only be Custer! And seven hundred strong, against this enormous mass of hostiles! No – it might be Crook, hitting back after his reverse at the Rosebud; this was far more likely, and he had twice as many men as Custer. Perhaps it was both of them, two thousand sabres; the Sioux would have their hands full if that were so.

(It wasn’t, of course. It was Reno, obeying orders, coming full tilt towards the Hunkpapa circle along the bank with a hundred-odd riders. And I called Raglan a fool!)

Across my front braves were hurrying upstream. One young buck was strapping on two six-guns as he ran, and a girl hurried after him with his eagle feather; he was shouting as she thrust it through his braid, and then he was away, and she standing on tiptoe with her knuckles to her mouth; two more braves I saw tumbling out of a tipi, one with a lance and his face painted half-red, half-black, and an old man and old woman hobbling behind them, the old fellow with an ancient musket which he was calling to the boys to take, but they never heard, and he stood there holding it forlornly; another old woman hurried by with a small boy, the bundle she was carrying burst open, and they both paused to scrabble in the dust until the kid shrieked and pulled the old girl aside as a thunder of hooves came from my left, and out from beneath the trees came as fine a sight (I speak as a cavalryman, you understand) as one could wish – a horde of feathered, painted braves, lances and rifles a-flourish, whooping like bedamned. Brulés and Minneconju, I think, but I’m no expert, and then there was another yell somewhere behind my tipi, and by humping out for a look I could see another mob of feathered friends making for the river, too – Oglala, I fancy, and everywhere there were braves on foot, with bows and rifles and hatchets and clubs, racing towards the sound of the firing, which was growing fiercer but, I thought, no nearer.

The Brulé riders were thundering by before me, shrieking their “Kye-kye-kye-yik!” and “Hoo’hay!”, and if ever you hear that from a Sioux, get the hell out of his way, because he isn’t asking you the time. The only worse noise he makes is “Hoon!” which is the equivalent of the Zulu “s’jee!” and signifies that he’s sticking steel into someone. Out before my tipi was the old singer, waving his arms and bawling:

“Go! Go, Lacotahs! It’s a good day to die!”

There’s a kindred spirit, thinks I – he wasn’t going. But the rest of them were, by gum, horse, foot, guns, bows, and every damned thing – these were the Sioux who weren’t going to fight, you recall. They vanished among the trees upstream, and the women and kids were away down in t’other direction by now – which left the world to sunlight and to me, more or less. Suddenly there was hardly a soul in sight between me and the river; a few stragglers, one or two old men, the ancient singer who had stopped encouraging the lads and was making tracks to his tipi. Upstream the firing was banging away as loud as ever – but I didn’t care for it. The boys in blue were making no headway at all; if anything, the crash of musketry was receding, which was damned discouraging.

Now, two things I must make clear. First, that I had not merely been viewing the stirring scene, but considering keenly which way salvation lay, and deciding to lie low. I was wearing four feet of timber across my neck, you see, with my hands bound to it, to say nothing of being painfully gagged, and while my feet were free, I felt I’d be a trifle conspicuous if I lit out from cover – and where to, anyway? Secondly, my memory, while acute for what I hear and see and feel in the heat of battle, is usually at fault where time is concerned. I’m not alone in that – any soldier will tell you that five minutes fighting can seem like an hour, or t’other way round. From the sound of the first shot I would guess that perhaps twenty minutes had passed, and now the sound of firing was decidedly fainter, when across the clearing Walking Blanket Woman came running – she’d pushed past me and disappeared, you remember, and here she was again, excited as all get-out.

“They are killing your pony-soldiers! Ai-ee!” cries the bloodthirsty biddy. “They are driving them back on the river! Everywhere they kill them! Ees! Soon all will be dead!”

She was rummaging in a corner of the tipi, and damme if she didn’t come up with a most ugly-looking hatchet and a long thin knife, which she tested on the ball of her thumb, grunting with satisfaction. Plainly she was going to join in the fun, no doubt to avenge her brother – and then she stopped and looked at me, and the light of battle died out of the saucy little face, and I could read her thoughts as clear as if she’d spoken.

“Drat!” she was thinking. “There’s this great idiot to look after, and me all over of a heat to help cut up the remains! How tiresome! Oh, well, someone’s got to mind the shop, I suppose – hold on, though! If I ‘look after’ him permanently, so to speak, I can go with a clear conscience … on the other hand, Jacket will be annoyed if he’s cheated of his little kakeshya – haven’t seen a good flaying and dismembering for ages myself, for that matter. But I would like to join the fun up yonder …”

It was such a winsome little face, too, but as the expressions chased one another across it my gorge rose. She was eyeing me doubtfully, thoughtfully, angrily, determinedly – and I was about to bolt headlong, yoke or not, when above the distant din of firing came another sound, so faint that for an instant I thought it was imagination, and yet it was quite close at hand, across the river.

She heard it too, and we both stood stock-still, straining our ears. It was just the tiniest murmur at first, and then the drift as of a musical pipe, far, far away. And while I’m well aware that the 7th Cavalry band was not present at Little Bighorn, I know what I heard, and all I can say is that some trooper had a penny whistle, and was blowing it. For there was no doubt – somewhere beyond the river, on the high bluffs a bare half-mile away, was sounding the music of Garryowen.

Walking Blanket Woman was beside me in an instant. We both stood staring over the trees. The bluffs were empty – and then on their crest there was a movement, and another a little behind, and then another, tiny objects just above the skyline, slowly coming into view – horsemen, and one of the foremost carrying a guidon, and then a file of troopers, and I could make out the shapes of fatigue hats – ten, twenty, thirty riders, and as they rode at the walk, the piping was clear now, and I found the words running through my head that the 8th Hussars had sung on the way to Alma:

Our hearts so stout have got us fame,

For soon ’tis known from whence we came,

Where’er we go they dread the name

Of Garryowen in glory.

The piping stopped, and I heard the shout of command faint over the trees. They had halted, and in the little knot of men round the guidon I caught a glint – field-glasses, sweeping the valley. Custer had come to Little Bighorn.

Perhaps I’m a better soldier than I care to think, for I know what I thought in that moment. My first concern should have been how the blazes to get across to them, but possibly because it was a long, steep way, and there was a young lady beside me at least toying with the notion of putting her knife-point to my ear and pushing, it seemed academic. And the instinctive order that I would have hollered across that river was: “Retire! And don’t tarry on the way! Get out, you bloody fool, and get out fast while there’s still time!”

He’d not have listened, though. Even as I watched I saw a tiny figure with hand raised, and a moment later the faint call of “Forward-o!” and they were coming on along the bluffs, and wheeling down into the coulee, and beyond the bluffs to their left was a sputter of shooting, and down the steep came a handful of Sioux at the run, and after them a party of Ree scouts, little puffs of smoke jetting after the fugitives. There were yells of alarm from far up the river, closer than the distant popping of the first fight, which had faded into the distance.

A bugle sounded on the bluffs, and the first troop was coming down the coulee – greys, and I thought I could make out Smith at their head. Had lunch with your wife and Libby Custer on the Far West recently, was the ridiculous thought that went through my mind. And behind them there came a sorrel troop – why, that would be Tom Custer, who’d wept at that ghastly play in New York. And there, by God, at the head of the column, was the great man himself; I could see the flash of the red scarf on his breast – and I almost burst my gag, willing him to stop and turn, for he was doing a Cardigan if ever a man did, and he couldn’t see it. The clamour in the trees upstream was rising now; I thought I could hear pony hooves, and from the left, along the water’s edge, came a mounted brave, yelling in alarm, waving his rifle above his head, and after him two more – Cheyenne, as I live, all a-bristle with eagle feathers and white bars of paint.

The girl gasped beside me, and I turned to look at her, and she at me. And what I tell you is strictest true: I looked at her, with a question in my eyes – Flashy’s eyes, you know, and I put every ounce of noble mute appeal into ’em that I knew how, and that’s considerable. God knows I’d been looking at women all my life, ardent, loving, lustful, worshipful, respectful, mocking, charming, and gallant as gadfrey, and while I’ve had a few clips on the ear and knees in the crotch, more often than not it has worked. I looked at her now, giving her the full benefit, the sweet little soul – and like all the rest, she succumbed. As I say, it’s true, and here I am, and I can’t explain it – perhaps it’s the whiskers, or the six feet two and broad shoulders, or just my style. But she looked at me, and her lids lowered, and she glanced across the river where the troopers were riding down the coulee, and then back at me – this girl whose brother had been killed by my people only a few days back. I can’t describe the look in her eyes – frowning, reluctant, hesitant, almost resigned; she couldn’t help herself, you see, the dear child. Then she sighed, lifted the knife – and cut the thongs securing my hands to the yoke.

“Go on, then,” says she. “You poor old man.”

Well, I couldn’t reply with my mouth full of gag, and by the time I’d torn it out she had gone, running off to the right with her hatchet and knife, God bless her.73 And I was cool enough to drain a bowl of water and chafe my wrists while I took in the lie of the land, because if I was to win across to Custer in safety it was going to be a damned near-run thing, and I must settle my plan in shaved seconds and then go bull at a gate.

To the right my girl was nearing the trees, and there were a few Indians in sight, but a hell of a lot more behind by the sound of it, no doubt streaming down from the first fight to give the boy general a welcome. Three Cheyenne had appeared from the left – and knowing them, I doubted if they’d be the only ones. By God, Custer had picked a rare spot to make his entry. The three Cheyenne were close to the bank, perhaps fifty yards away on my left front, arguing busily with a couple of Indians on foot; they were pointing up towards the ford and doubtless remarking that the pony-soldiers would shortly be crossing it and charging through the heart of the village. At that moment, out from between the tipis on my right came the old singer, leading a pony and yelling his head off.

“Go! Go, Lacotahs! See where the Long Knives come! The sun is on the hawk and the quarry! Hoo’hay! It’s a good day to die!”

If I’d been the Cheyenne I’d have spat in his eye – for one thing, they weren’t Lacotahs, and no doubt sensitive. But now was my moment. I looked across the river; the 7th were fairly pouring down the coulee, so far as I could see, for the farther they got down, the more they were obscured by the trees on the banks. The bugle was shrilling, shots were cracking on my side of the river, the three Cheyenne were apparently fed up with arguing, for they were skirting up towards the ford – and my ancient with his led pony was hobbling in their direction, shouting to the two dismounted chaps to take his steed and good luck, boys. I took a deep breath and ran.

The old fool never knew I was there until I was on the pony’s back. It might have been ten seconds, probably less, but time for me to realise that I was in such poor trim, what with my ordeal, aching limbs, too much tuck, booze, and cigars, and general evil living, that if he and I had run a race, the old bugger would have won, by yards. But he was looking ahead, yelling:

“Here! Calf, Bobtail Horse! Mad Wolf! Here’s a pony! Climb aboard, one of you fellows, and smite the white-faces, and my blessing go with you!” Or words to that effect.

I hauled myself on to the beast, grabbed the mane, and dug in my heels. I know people were running somewhere to my right, the Cheyenne were trotting purposefully towards the ford, shots were flying all along the river banks – and dead ahead of me, under the cottonwoods, was the ford leading to the coulee. Behind me the dotard was yelling:

“Go on, Lacotah! Here is a brave heart! See how he flies to meet the Long Knives!”

Apparently under the impression that I was one of the lads. The three Cheyenne were moving well, too – four of us going hell-for-leather, more or less in line abreast, three in paint and feathers, waving lances and guns, and one in white tie and tails, somewhat out of crease. Possibly they, too, thought that I belonged to the elect, for they didn’t so much as spare me a glance as we converged on the ford.

They were three good men, those – again I speak objectively – for they were going bald-headed against half a regiment, and they knew it. If the Indians put up statues, I reckon those three Cheyenne would be prime candidates, for if anyone turned the tide of Greasy Grass, they did. Mind you, I’m not saying that if Custer had got across the ford, he’d have had the battle won; I doubt it myself. He’d have got cut up either side, I reckon. But the first nails in his coffin were Roan Horse, Calf, and Bobtail Horse – and possibly my humble self – for it was our appearance at the ford, I think, that checked his advance. I don’t know – except that when my pony hit the shallows, with the three Cheyenne close behind, I lifted up mine eyes to the hills and saw to my amazement that the troopers in the coulee were dismounting and letting fly with their carbines. Whether the three Cheyenne stopped or came on,74 I don’t know, for I wasn’t looking; there were shots buzzing like bees overhead as I scrambled up the bank – and not twenty yards away a Ree scout and a trooper were covering me with their carbines, and I was bawling:

“Don’t shoot! It’s me! I’m white! Hold your fire!”

One did, t’other didn’t, but he missed, thank God, and I was careering over the flat to the mouth of the coulee, hands raised and holding on with my aching knees, yelling to them not to shoot for any favour, and a knot of bewildered men were standing at gaze. There was E Troop’s guidon, and as I half-fell from my pony, there was Custer himself, all red scarf and campaign hat, carbine in hand. For a second he stared speechless, as well he might; then he said “Good God!” quite distinctly, and I replied at the top of my voice:

“Get out of it! Get out – now! Up to the top and ride for it!”

Somehow he found his tongue, and as God’s my witness the next thing he said was: “You’re wearing evening clothes!” and looked beyond me across the river, doubtless to see if other dinner guests were arriving. “How in—”

I seized him by the arm, preparing to yell some more until common sense told me that calm would serve better.

“George,” says I, “you must get out quickly, you know. Now! Mount ’em up and retire, as fast as you can! Back up this draw and on to the bluffs—”

“What d’you mean?” cries he. “Retire? And where in creation have you come from? How the deuce—”

“Doesn’t matter! I tell you, get this command away from here or you’re all dead men! Look, George, there are more Indians than you’ve ever seen over yonder; they’re beating the tar out of someone upriver, and they’ll do the same for you if you stay here!”

“Why, that’s Reno!” cries he. “Have you seen him?”

“No, for Christ’s sake! I haven’t been within a mile of him, but it’s my belief he’s beat! George, listen to me! You must get out now!”

Tom Custer was at my elbow. “How many hostiles over yonder?” snaps he.

“Thousands! Sioux, Cheyenne, God knows how many! Lord above, man, can’t you see the size of the village?” And in fury I turned to look – sure enough, they were swarming up to the ford from both directions, mounted Cheyenne among the trees downriver, now hidden, now in sight, like trout darting through weed, but coming by hundreds, and from the trees upstream a steady rattle of musketry was coming; balls were whizzing overhead and whining up the coulee; there were shouts of command to open fire coming from above us.

“Mount!” roars Custer. “Smith – E Troop! Prepare to advance! Tom, with your troop, sir!” He turned to bellow up the coulee. “Captain Yates, we’re going across! Bugler, sound!” He swung himself into his saddle, and behind was the creak and jingle and shouting as the troopers took their beasts from the holders, and a scout appeared at Custer’s side, pointing across the river.

“He’s right, Colonel! Didn’t I say – we go in there, we don’t come out!”75

It must have been obvious to anyone who wasn’t stark mad. But Custer was red in the face and roaring; he swung his hat and yelled at me.

“Come on, Flash! Forward the Light Brigade, hey? Didn’t I know you’d be in at the death?”

“Whose bloody death, you infernal idiot?” I yelled back, and grabbed at his leg. “George, for God’s sake—”

“What are you about, sir?” cries he angrily. “I’ll—” And at that moment he jerked back in his saddle, and I saw the splash of crimson on his sleeve even as his horse surged past me. He didn’t tumble – he was too good a horseman for that – but he reined in, and at that moment one of the Ree scouts close by spun round and fell, blood spouting from his neck. Shots were kicking up the dust all about us, a horse screamed and went down, thrashing – by George, that had been a regular volley, at least thirty rifles together, which you don’t expect from savages; across the river a perfect mob of them was closing on the ford, halting to bring up their pieces and bows for another fusilade, a scarlet-clad figure ahead of them, arms raised, to give the word. I flung myself flat as shots and arrows whizzed past, and came up to see Custer standing in his stirrups, blood running over his right hand.

“F Troop! Covering fire! Tom! Smith! Move out with your troops!” Thank God he’d seen sense; he was pointing up the hillside, away from the bluffs. “Retire out of range! Bugler, up to Captain Keogh, and I’ll be obliged if he and Mr Calhoun will hold the crest yonder – you see it, on the top, there? – with their troops! Go!” He urged his beast up the coulee. “Yates, sweep that bank yonder!” He pointed across the water, but already Yates’s troop was blazing away, and Smith and Tom Custer were urging their men over the northern bank of the coulee, upwards towards the Greasy Grass slope that lay between the crest and the river. I was among them, clawing my way up the coulee side on to the rough hilly ground in the middle of a hastening crowd of troopers, a few mounted, but mostly leading their beasts. I swung myself aboard one of the led ponies, arguing blasphemously with its owner as we jogged over the hillside; shots were still buzzing past, and here was another draw across our front over which we scrambled. Drawing rein as the bugle blared again, I had a moment to collect myself and look round.

A bare hundred yards away, at the foot of the slope, the trees were alive with hostiles, firing raggedly up at us. There were three troops on the slope round about where I was; when I looked up the hill, there were I and L Troops skirmishing out in good order. Custer was sliding down from his pony, using one hand and his teeth to tie a handkerchief round his grazed wrist; I ran to him and jerked the ends tight.

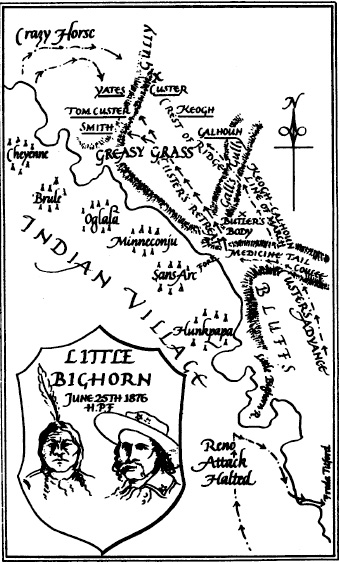

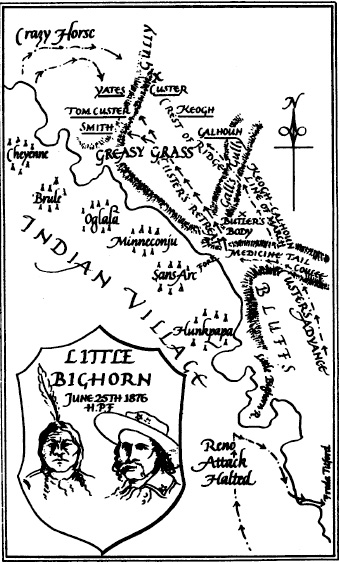

“Good man!” he gasped, and looked about. I don’t know if he saw what I already knew, although it was too late now. Take a squint at my map and you’ll see it. He’d come the wrong way.

I ain’t being clever, but if he’d done what I’d told him he might have saved most of his command – by withdrawing straight up Medicine Tail Coulee and making a stand on the high bluffs, where five troops could have held off an army. Or, if he’d retired flat out, Calhoun and Keogh could certainly have saved their troops. By coming across to the Greasy Grass slope he’d put his command out in the open, where the redskins could skirmish up over good broken ground and our only hope was to achieve the hill at the far end of the crest and make good a position there. And we might have done it, too, if that red-jacketed bastard Gall hadn’t been an Indian in a million – that is, an Indian with an eye for ground like Wellington. The little swine saw at once how we’d blundered, and exactly what he must do.

It’s a simple, tactical thing, and for those of you who ain’t sure what turning a flank means, it’s a fair example. See on the map – we had to make for the hill marked X, with half the Sioux nation coming up from the ford at our heels. If they’d simply pursued us straight, we’d likely have reached it, but Gall saw that the crest between the bluffs and the hill was all-important, and as soon as we were out on the Greasy Grass slope he had his warriors pouring up the second coulee in droves, nicely under cover until they could get high enough up to emerge all along the line of the second coulee, especially at the crest itself, where they could hit at I and L troops, and be well above Custer’s three other troops making for the hill. Smart Indian, fighting the white man in the white man’s way, and with overwhelming strength to make a go of it. In the meantime his skirmishers coming up on us from the river were pressing us too hard to give Custer time to regroup for any kind of counter-stroke. He couldn’t charge downhill, for even if he’d scattered our pursuers he’d have been stopped by the river with Keogh’s folk stranded; all he could do was retire to the hill with Keogh falling back the same way.

Our fellows were all dismounted, in three main groups across the slope, leading their horses and firing down at the Indians, who were swarming up through the folds and gullies, blazing away as they came. Curiously, I don’t think we’d lost many men yet, but now troopers began to fall as the slugs and arrows came whistling out of the blue. And I saw the first example of something that was to happen horrid frequent on that slope in the next fifteen minutes – a trooper kneeling with his reins over his arm, raving obscenely as he dug frenziedly with his knife at a spent case jammed in his carbine. That’s what happens: some factory expert don’t test a weapon properly, and you pay for it out on the hill when the rim shears off and your gun’s useless.

“Tell Smith to close up with E Troop!” yells Custer, and I saw the hostiles were up with Smith fifty yards below us in a murderous struggle of pistols and lances, hatchets and carbine butts. To our own front they were surging up, ducking and firing, and we were retreating, firing back; I stumbled over a little gully through a clump of thistles, fell on my face – heard the rattle within a foot of my ear, and there was a snake gliding under my nose into the dusty grass; I never even thought about him.

“Give me a gun, for pity’s sake!” I yelped, and Custer flung away his jammed carbine and threw me one of his Bulldog repeaters while he drew the other for himself. Christ, they were a bare ten yards off, shrieking painted faces and feathered heads racing towards me; I fired and one fell sprawling at my feet, guns were blasting all about me, Custer (he was cool, say that for him) was firing with one hand while with his wounded one he was thrusting a packet of cartridges at me. I saw the lens of his field-glasses splinter as a shot hit them; there were a dozen of us clawing our way backwards up out of a gully, firing frantically at the red mob pouring down the other bank. We broke and ran, in a confusion of yelling swearing men and rearing horses; below on the slope a body of kneeling troopers with their sorrels behind them – Tom Custer’s people – were firing revolver volleys at our pursuers, and behind me as I flew were shrieks of agony blending with the war-whoops.

Flashman’s map of Little Bighorn is erratic in details – the course of the river, and the placing of the various tribal camp circles – but agrees with most authorities in showing Custer’s advance along the bluffs, down Medicine Tail Coulee to a point near the ford, and then north up the Greasy Grass slope in an attempt to reach the hill marked X, where the remnants of his force were caught between the Indian charge from Gall’s Gully and the encircling movement of Crazy Horse’s cavalry. The underlined names (e.g. CUSTER) show where the various troops died with their commanders.

“Steady!” roars Custer. There he was, shoving rounds into his Bulldog and firing coolly, picking his men while the arrows whizzed round him. “Fall back in order! Close on C Troop!” Beside him a trooper with the guidon staggered, an arrow between his shoulders; Custer wrenched the staff from him and plunged uphill; I scrambled up beside him, swearing pathetically as I fumbled shells into my revolver – and for a moment the firing died, and Yates was beside me, yelling something I couldn’t hear as I staggered to my feet.

We were in a long gully running from the hill-top to the trees far down by the river. The slopes below me were littered with bodies – the blue of troopers among the Indians, and lower still Indian attackers were bounding up the gully sides. The remnant of Smith’s troop was reeling up the gully, turning and firing, loose horses among them, redskins racing in to grapple at close quarters. I heard the hideous “Hoon! Hoon!” as the clubs and hatchets swung and the knives went home, and the crash of Army pistols firing point-blank. Around me were what was left of Yates’s troop, staggering figures streaked with dust and blood; just down the slope Tom Custer’s fellows were at grips with a horde of painted, shrieking braves, slashing and clubbing at each other hand to hand. I struggled out of the gully; in its bed a trooper was lying, screaming and plucking feebly at a lance buried in his side, two Indians dead beside him and a third still kicking. I looked back across the gully – and saw the final Death bearing down upon us.

Across the upper slopes of the Greasy Grass they came, hundreds of running, painted figures, and on a pony among them that crimson leader, waving them on for the kill. Tom Custer’s tattered remnant was breaking clear of a tangled mêlée of blue-shirted and red half-naked fighters who still hacked and stabbed and shot at each other; somewhere on the crest I knew Keogh’s people must be struggling with the right wing of that Indian charge sweeping across the slope. In less than a minute they would be on us; I turned sobbing to run for the hill-top, a bare hundred yards away – and even in that moment it crossed my mind: we’ve come a long way damned fast, for I’d no notion it was so close. We must have retreated a good mile from the ford where I’d ridden across with the Cheyenne just a moment ago.

Custer was on his feet, reloading, looking this way and that; his hat was gone, his hand was caked with dried blood. There were about forty troopers round him, firing past me down the hill. As I came up to them an arrow-shower fell among us; there were screams and groans and raging blasphemy; Yates was on the ground, trying to staunch blood pumping from a wound in his thigh – artery gone, I saw. Custer bent over him.

“I’m sorry, old fellow,” I heard him say. “I’m sorry. God bless all of you, and have you in His keeping.”

There was a slow moment – one of those which you get in terrible times, as at the Balaclava battery, when everything seemed to happen at slow march, and the details are as clear and inevitable as day. Even the shots seemed slower and far-off. I saw Yates fall back, and put up a hand to his eyes like a man who’s tired and ready for bed; Custer straightened up, breathing noisily, and cocked his Bulldog, and I thought, you don’t need to do that, it’s British-made and fires at one pressure; a trooper was crying out: “Oh, no, no, no, it’s a damned shame!” and the F Troop guidon fell over on a wounded sergeant, and he pawed at it, wondering what it was, and frowned, and tried to push its butt into the ground. On the crest behind them I saw a sudden tumult of movement, and thought, ah yes, those are mounted Sioux – by Jove, there are plenty of them, and tearing down like those Russians at Campbell’s Highlanders. Lot of warbonnets and lance-heads, and how hot the sun is, and me with no hat. Elspeth would have sent me indoors for one. Elspeth …

“Hoo’hay, Lacotah! It’s a good day to die! Kye-ee-kye!”

“You bloody liars!” I screamed, and all was fast and furious again, with a hellish din of drumming hooves and screams and war-whoops and shots crashing like a dozen Gatlings all together, the mounted horde charging on one side, and as I wheeled to flee, the solid mass of red devils on foot racing in like mad things, clubs and knives raised, and before I knew it they were among us, and I went down in an inferno of dust and stamping feet and slashing weapons, with stinking bodies on top of me, and my right hand pumping the Bulldog trigger while I gibbered in expectation of the agony of my death-stroke. A moccasined foot smashed into my ribs, I rolled away and fired at a painted face – and it vanished, but whether I hit it or not God knows, for directly behind it Custer was falling, on hands and knees, and whether I’d hit him, God knows again. He rocked back on his heels, blood coming out of his mouth, and toppled over,76 and I scrambled up and away, cannoning into a red body, hurling my empty Bulldog at a leaping Indian and closing with him; he had a sabre, of all things, and I closed my teeth in his wrist and heard him shriek as I got my hand on the hilt, and began laying about me blindly. Indians and troopers were struggling all around me, a lance brushed before my face, I was aware of a rearing horse and its Indian rider grabbing for his club; I slashed him across the thigh and he pitched screaming from the saddle; I hurled myself at the beast’s head and was dragged through the mass of yelling, stabbing, struggling men. Two clear yards and I hauled myself across its back, righting myself as an Indian stumbled under its hooves, and then I was urging the pony up and away from that horror, over grassy ground that was carpeted with still and writhing bodies, and beyond it little knots of men fighting, soldiers with clubbed carbines being overwhelmed by waves of Sioux – but there was a guidon, and a little cluster of blue shirts that still fired steadily. I rode for them roaring for help, and they scrambled aside to let me through, and I tumbled out of the saddle into Keogh’s arms.

“Where’s the General?” he yelled, and I could only shake my head and point dumbly towards the carnage behind me – but it wasn’t visible, and I saw that somehow I’d ridden over the crest, on the far side from the river, and the crest itself was alive with Indians firing at us, rushing closer and firing again. Keogh yelled above the din:

“Sergeant Butler!” A ragged blue figure was beside him, gold chevrons smeared with blood and dust. “Ride out! See if you can find Major Reno! Tell him we’re hemmed in and the General’s dead!”

He shoved hard at Butler, who turned and slapped the neck of a bay horse that was lying among the troopers; it came up, whinnying, at his touch, and as Butler grabbed the reins he came face to face with me, and he must have seen me at Fort Lincoln, for he said:

“’Allo then, Colonel! Long way from ’Orse Guards, ain’t we, though?” Then he was up and away, head down, going hell for leather at the advancing Sioux,77 and thinks I, by God, it’s that or nothing, and scrambled on my own beast as the red tide flooded in amongst us. It was like Scarlett’s charge, a mass of men close-packed, contorted faces, white and red, all about me, carrying me and the horse whether we would or no, and there was no time to think or do anything but swing my sabre at every eagle feather in sight, screaming wildly as the mass of men disintegrated and I dug in my heels and went in blind panic. As I fled I lifted my head and gazed on such a scene as even I can hardly match from all my memories of bloody catastrophe.

Until this moment, you’ll agree, I’d had little time for careful thought or action. From the moment I’d crossed the ford and tried to reason with Custer, it had been one shot-torn nightmare of struggle up the slope away from those hordes of red fiends, followed by the chaos when our retreat had been caught in the death-grip between Gall’s charge and the mounted assault (led, I’m told, by Crazy Horse in person) over the very hill to which we’d been struggling for safety. Now, with Keogh’s troop being engulfed behind me, I was recrossing the crest overlooking the whole Greasy Grass slope to the river at its foot; I wasn’t there above an instant, but I’ll never forget it.

Below me the hillside was covered with dead and dying, and with little clusters where shots still rang out – a few desperate wretches taking as many Sioux with them as they could. There were hundreds of figures running, riding, and some just walking, across the slope, and they were all Indians. Most of them were hurrying across my front to the struggle still boiling just below the hilltop where Custer’s group were dying. There may have been a score of them, I can’t tell, standing and lying and sprawling in a disordered mass, the pistols and carbines cracking while the mounted wave of war-bonnets and eagle feathers rode round and through and over them, the clubs and lances rising and falling to the yells of “Hoon! Hoon!” while Gall’s footmen grappled and stabbed and scalped at close quarters. There was no guidon flying, no ring of blue shoulder to shoulder, no buckskin figure with flowing locks and sabre (he was one of the still forms in that crawling mêlée); no, there was just a great hideous scrimmage of bodies, like a Big Side maul when the ball’s well hidden – only here it was not “Off your side!” but “Hoon!” and the crash of shots and flash of steel. That was how the 7th Cavalry ended. Bayete 7th Cavalry.

Elsewhere it was already over. Far down to my left a mob of Indians were shooting and stabbing and mutilating over a long cluster of blue forms – that would be Calhoun’s troop. Straight ahead below me, to the right of the long gully, the cavalry dead lay thick where Yates and Tom Custer and Smith had died with their troops – but far down there was still a group mounted on sorrels, and I could see the puffs of smoke from their pistols.

All this I took in during one long horrified second – it couldn’t have been longer or I wouldn’t be here. I doubt if I even checked stride, for one glance behind showed a dozen mounted braves and a score running, and they all had Flashy in their sights. To the left and below the slope was thick with the bloodthirsty bastards – all you can do is see where the enemy are thinnest and go like hell. I swerved right in full career, for there was a break of perhaps ten yards in the mob surging up to join in the massacre of Custer’s party. I went for it, sabre aloft, bawling: “I surrender! Don’t shoot! I’m not an American! I’m British! Christ, I ain’t even in uniform, blast you!”, and if anyone had shown the least inclination to say: “Hold on, Lacotahs! Let’s hear what he has to say”, I might have checked and hoped. But all I got was a whizzing of arrows and balls as I tore through the gap, rode down two braves who sprang to bar my path, cut at and missed a mounted fellow with a club, and then I was thundering down the right side of the gully towards the group on their sorrels – and they weren’t there! Nothing but bloody Indians hacking and stabbing and snatching at riderless beasts. I tried to swerve, aware of a mounted lancer coming up on my flank, a painted face beneath a buffalo helmet; he veered in behind me, I screamed as in imagination I felt the steel piercing my back, hands were clutching at my legs, painted faces leaping at my pony’s head, my sabre was gone, an arrow zipped across the front of my coat, something caught the pony a blow near my right knee – and then I was through the press,78 only a few Indians running across my front, when an arrow struck with a sickening thud into the pony’s neck. As it reared I went headlong, rolling down a little gully side and fetching up against a dead cavalryman with his body torn open, half-disembowelled.

I lay sprawled on my back as two of those screaming brutes came leaping over the bank. They collided with each other and went down, and behind them the buffalo-cap lancer was sliding from his saddle, jumping over the other two, swinging up his hatchet. His left hand was at my throat, the frightful painted face was screaming a foot from mine. “Hoon!” he yelled, and his hatchet flashed down – into the ground beside my head. His breath was stinking against my face as he snarled:

“Lie still! Lie still! Don’t move, whatever happens!”

Up went his hatchet – and again it missed my face by a whisker, and his left hand must have been busy with the dead trooper’s innards, for a bloody mess was thrust into my face, and then he had a knife in his hand; it flashed before my eyes, there was a blinding pain on top of my skull, but I was too choked with horror, physical horror, to scream, and then he was on his feet, yelling exultantly.

“Another of them! Kye-ee! Go find your own, Lacotahs!”

I didn’t see this, blinded with pain and human offal as I was, but I heard it. I lay frozen while they snarled at each other. There was blood running into my eyes, my scalp was a fire of agony – oh, I knew what had been done to me, all right. But why hadn’t he killed me?

“Just lie still. I’m robbing your corpse,” growled a voice close to my ear, and his hands were delving into my pockets, tearing at my coat, dragging my shirt half over my bloodied face – the laundry would certainly refuse my linen after today. Who the hell was he? I wanted to shriek with pain and fear, but had just wit enough not to.

“Easy does it,” muttered the voice. “Scalping ain’t fatal; it’s just a nick. Have you any other wound? If you haven’t, and understand what I’m saying, move the little finger of your right hand the least bit … good … and don’t move another muscle – there are six of ’em within twenty yards, and I’m just muttering curses to myself, but if you start thrashing about, they may be curious. Lie still … lie still …”

I lay still. By God, I lay still, with my head splitting, while he emptied my pockets and suddenly shouted:

“Get away, you Minneconju thief! This one’s mine!”

“That’s not a pony-soldier!” snarled another voice. “What’s that shining thing you’ve got?”

“Something too good for you, scabby-head!” cries my boy. “This is a white man’s clicky-thing. See – it has a little splinter that moves round. Oh, you can have it if you like – but I’ll keep his dollars!”

“It’s alive, the clicky-thing!” cries the other. “See, it does move! Hinteh! Hiya, what do I want with it? Give me the dollars, eh, Brulé – go on!”

I heard a jingle of coins, and someone shuffling away, and all around me, through the waves of pain and fear, I could hear a ceaseless chorus of groans and screams and exultant yells, and one awful bubbling high-pitched shriek of agony – some poor bastard hadn’t been killed outright. Occasional shots, wailing voices raised in chants, and all about my head flies buzzing, crawling on my head; I was matted with blood and stifling with filth, and the sun’s heat was unbearable – but I lay still.

“He’s gone,” growled my unseen preserver. “Didn’t want your watch – lie still, you fool!”

For I had jerked automatically as it dawned on me – to the Minneconju he’d spoken Siouxan, but all the words he’d addressed to me had been in English! Good English, too, with a soft, husky American accent. There it was again: “Keep lying still. I’m going to sit up on the bank above you and sing a song of triumph. For the destruction of all the pony-soldiers, d’you see? Right … there’s no one here but us chickens at present, but it won’t get dark for another four hours, I guess. Then we’ll get you away. Can you play possum that long? Move your pinky if you can … that’s the ticket. Now, take it easy.”

I was past wondering; I didn’t care. I was alive, with a friend close by, whoever he might be. For the rest, I still hadn’t taken in the horror of it. Half a regiment of US cavalry had been massacred, wiped out, in barely quarter of an hour.79 Custer was dead. They were all dead. Except me.

“Don’t go to sleep,” said the voice. “And don’t get delirious, or I’ll dot you a good one. Right, listen to this.”

And he began to chant in Siouxan, about how he had slain six pony-soldiers that day, including a Washechuska English soldier-chief with a watch from Bond Street which was still going and the time was ten past five. Which beggared imagination, if you like. Then he went on about what a great warrior he was, and how many times he had counted coup, and I lay there with the flies eating me alive. Ne’er mind, worse things can happen.

I must have slept, in spite of his instruction, or more likely it was a long faint, for suddenly I was cold, and an arm was round my shoulders, easing me up, and water was being dashed in my face and a cloth was sponging away the caked blood. A bowl was held to my parched mouth, and the American voice was whispering:

“Gently, now … a sip at a time. Good. Now lie still a while till I get you smartened up.”

I gulped it down, ice-cold, and managed to get my gummed eyelids opened. It was dusk, with stars beginning to show, and a chill wind blowing; beside me knelt the fellow in the buffalo-helmet, a fearsome sight and no prettier when he grinned, which he did when I croaked for information who he might be.

“Let’s say a resurrectionist. Can you walk? All right, I’ll carry you a piece, but then you’ll have to sit a pony. First of all, let’s get you looking like one of the winning team.”

He dragged off my clothes, and somehow got me into a buckskin shirt and leggings. My head was aching fit to split, and wasn’t improved when he insisted on putting his buffalo-cap on it. In the dim light I saw his long hair hung to his shoulders, and his face was bright with paint; American or half-breed, he’d taken pains with his make-up.

“Now, listen close,” says he. “There are still braves and women around, collecting the dead.” Sure enough, the evening was being broken by the high-pitched keening of the death-songs; against the night sky I could see figures moving to and fro, and there were pin-points of torch-light all over the slope. “All right, we’re going downstream, to a ford farther along; that way we can skirt the village, and I’ll get you to a place where you can lie up a spell. Hoo-hay, let’s go.”

I could just stumble, with him holding me. Then there was a pony, and he was helping me up; I reeled in the seat, with his arm about me, but although my head was bursting with pain I managed to balance, just. Then we moved slowly forward through the gathering night, down a slope and under cottonwoods; I could hear the river bubbling near. But I was like a man in a dream; time meant nothing, and I was only now and then aware that I was still astride a pony, that it was splashing through water, that we were mounting a slope. Twice I was falling from my seat when he caught me and held me upright. How long we rode I can’t tell. I remember a moon in the sky, and a hand on my shoulder, and then I know I was lying down, and a deep voice was speaking in Siouxan, from very far away.

“… put the grease on his head, and if it becomes angry send for me. No one will come, but if they do, and they are of our people, tell them he is to stay here. Tell them that this is my word. Tell them the One-Who-Catches has spoken …”

b Torture.