Palestinians in the territories live under Israeli military occupation. They are not citizens of Israel or of any state, and have no rights of protest or redress. The occupation is a violent daily reality, in which Israeli soldiers, checkpoints, tanks, helicopter gunships, and F-16 fighter jets control every aspect of Palestinian lives, and have recently brought social, family, and economic life to a virtual halt. In summer 2002, the US Agency for International Development determined that Palestinian children living in the occupied territories faced malnutrition at one of the highest levels in the world—higher than in Somalia and Bangladesh. By the summer of 2006, UN humanitarian agencies warned that poverty in Gaza was close to 80 percent, and unemployment over 40 percent. The occupation has been in place since 1967, although the current period has seen perhaps the most intense Israeli stranglehold on Palestinian life, and the highest levels of violence. What we often hear described simply as “the violence” in the Middle East cannot be understood without an understanding of what military occupation means.

Violence is central to maintaining Israel’s military occupation. It is carried out primarily by Israeli military forces and Israeli settlers in the occupied territories who are themselves armed by the Israeli military, and its victims include some Palestinian militants and a large majority of Palestinian civilians, including many children. Because military occupation is itself illegal, all Israeli violence in the occupied territories stands in violation of international law—specifically the Geneva Conventions that identify the obligations of an occupying power to protect the occupied population.

Palestinian violence is the violence of resistance, and has escalated as conditions of life and loss of hope breed greater desperation. It is carried out primarily by individual Palestinians and those linked to small armed factions, and is aimed mostly at military checkpoints, soldiers, and settlers in the occupied territories; recently more attacks, particularly suicide bombings, have been launched inside Israel, many of which have targeted civilian gathering places. Those attacks, targeting civilians, are themselves a violation of international law. But the overall right of an occupied population to resist a foreign military occupation, including through use of arms against military targets, is recognized as lawful under international law.

Beyond the general concern about human suffering, many Americans have a special interest in events in the region because the US government is by far the most dominant outside power there, and decisions made in Washington are central to developments toward war or peace. And further, the US sends billions of our tax dollars in aid to the region, including about $4 billion in annual aid to Israel alone.

US, British, and European policy in the Middle East also plays a major role in determining how people in that region view our governments and citizens. If we are concerned about the rise in international antagonism not only to US policies but toward individual citizens of our countries, we need to take seriously what our governments do in our name elsewhere in the world.

From 1967, through the beginnings of the twenty-first century, US policy in the region has been based on protecting the triad of oil, Israel, and stability. “Stability” has always been understood to include access to markets, raw materials, and labor forces for US business interests, as well as the stability imposed by the expansion of US military capacity throughout the region, including the creation of an elaborate network of US military bases. During the Cold War the US relied on Israel as a cat’s paw—a military extension of its own strategic reach—both within the Middle East region and internationally in places as far as Angola, Guatemala, Mozambique, and Nicaragua. With the end of the Cold War, Israel remains a close and reliable ally, in the region as well as internationally, for the now unchallenged power of the US—although the strategic value of Israel, in an era shaped by the US’s efforts to dominate countries and regions particularly antagonistic to Israel, appears to be diminishing. At the same time, widespread domestic support for Israel, most concentrated in the mainstream Jewish community and among the increasingly powerful right-wing Christian fundamentalists in the US, took root in popular culture and politics, giving Israel’s supporters great influence over Washington policymakers.

As the al-Aqsa Intifada ground on, Israel escalated to the use of tank-mounted weapons, helicopter gunships firing wire-guided missiles on buildings and streets to carry out targeted assassinations, and finally F-16 fighter bombers, which dropped 2,000-pound bombs in refugee camps and on crowded apartment buildings, resulting in significant civilian casualties.

Palestinians, unlike during the unarmed first intifada (1987–1993), had and used small arms, mainly rifles, against Israeli soldiers, tanks, and sometimes settlers; they also fired Qassam rockets that hit both military and civilian targets inside Israel. As the situation became more desperate, some young people turned themselves into suicide bombers, attacking either military checkpoints in the occupied territories, or civilian gathering spots inside Israel itself.

Israel has every right to arrest and put on trial anyone attempting to attack civilians inside the country. But it does not have the right to occupy a neighboring country, and if it is serious about ending attacks on civilians, it must be serious about ending that occupation.

Israel is occupying Palestinian land and harshly controlling Palestinian lives; Palestinian violence, even those extreme and ultimately illegal actions such as lethal attacks on civilian targets, is a response to that occupation. Israel does not have the right, under international law or United Nations resolutions, to continue its occupation, let alone to use violent methods to enforce it.

Since September 11, Israeli politicians led by Prime Minister Ariel Sharon and his successor Ehud Olmert have ratcheted up their rhetoric equating the US “war on terrorism” in Afghanistan and later Iraq with Israeli assaults in the occupied Palestinian territories. Immediately after the September 11 attacks, former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu blurted out, “It’s very good.” Then, editing his words, he added, “Well, not very good, but it will generate immediate sympathy.”

Israel has also used the escalating fear of terrorism in the US after September 11 to increase its support (financial, diplomatic, and political) from Congress and the American people. In fact, the Bush administration’s post-September 11 embrace of the extremist Sharon government has allowed new threats of even more dire Israeli attacks against Palestinians— up to and perhaps including forced “transfer” of Palestinians out of the occupied territories—to go unchallenged by Washington and to become part of normal political discourse inside Israel.

The vast majority of Palestinians have never participated in any armed attack against anyone. Many, perhaps most, Palestinians are opposed to attacks on civilians anywhere, and many are opposed to any attacks inside Israel. In the spring of 2002, a large group of well-known Palestinian intellectuals signed a public statement condemning suicide bombings against civilians. But virtually all Palestinians understand the desperation and hopelessness that fuel the rage of suicide bombers and their increasing (and ever-younger) followers.

From Israel’s creation in 1948 until 1966, the indigenous Palestinian population inside the country lived under military rule. Since that time, Palestinians have been considered citizens, can vote and run for office; several Palestinians serve in the Israeli Knesset, or parliament. But not all rights inside Israel are granted on the basis of citizenship. Some rights and obligations, sometimes known as “nationality rights,” favor Jews over non-Jews (who are overwhelmingly Palestinian) in social services, the right to own land, access to bank loans and education, military service, and more.

More than three times as many Palestinians live under Israeli military occupation in the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem than remain inside Israel proper. Millions more remain refugees.

Throughout the years of the Arab and then Ottoman empires in what is now the Arab world, there were no nation-states; instead the political demography was shaped by cities and regions. As in most parts of the Arab world, modern national consciousness for Palestinians grew in the context of demographic changes and shifts in colonial control. During the 400 years of Ottoman Turkish control, Palestine was a distinct and identifiable region within the larger empire, but linked closely with the region then known as Greater Syria. With World War I and the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, Palestine became part of the British Empire. But even before that, beginning in the 1880s, the increasing influx of European Jewish settlers brought about a new national identity—a distinctly Palestinian consciousness—among the Muslims and Christians who were the overwhelming majority of Palestinian society. The indigenous Palestinians— Muslims and Christians—fought the colonial ambitions of European Jewish settlers, British colonial rule during the inter-war period, and the Israeli occupation since 1948 and 1967.

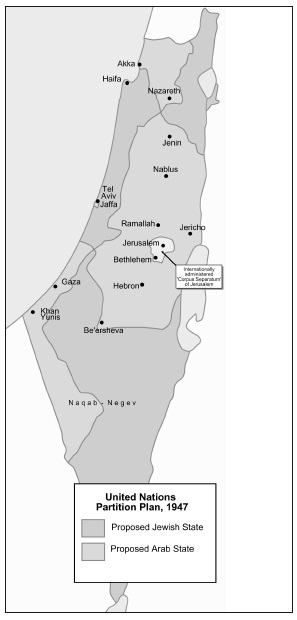

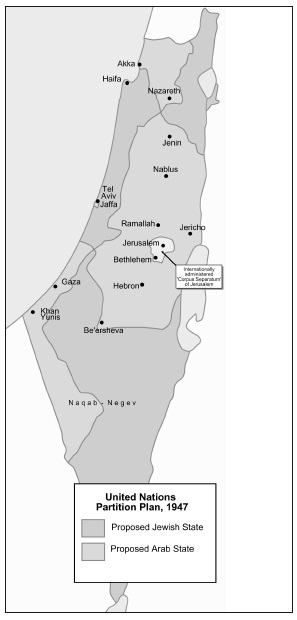

In the 1967 war, Israel took over the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, the last 22 percent of historic Palestine. Those areas are now identified as the occupied territories.

During the second intifada, settlement construction and expansion escalated. The curfews and closures, or blockades, of Palestinian towns and cities, once an occasional disruption, became constant. The re-occupation of Palestinian cities was matched by a complete division of the West Bank into scores of tiny cantons—villages cut off from each other, small towns cut off from the main roads, cities surrounded as in medieval sieges. Armed checkpoints, huge earth berms dug by armored tractors, and the destruction of roads all served to prevent Palestinians from moving within the territories, let alone traveling into Israel. Inevitably the economic shortages were severe; truckloads of produce rotted in the sun at checkpoints, milk soured, workers could not get to their jobs. Humanitarian crises spiked, with women giving birth at checkpoints because soldiers would not allow them to pass, victims of settler or soldier violence dying because military officers would not authorize Palestinian ambulances to move. In June 2006, the World Food Program reported that 70 percent of the Gaza population were unable to cover their daily food needs without outside assistance.

Israeli military control also means complete dependence on Israel for permits—to travel out of the country, to enter Israel from the West Bank to get to the airport to leave the country, for a doctor to move from her home village to her clinic in town, for a student to go to school. Most of the time, these permits remain out of reach.

In the summer of 2005, Israel withdrew its soldiers and settlers from the territory of the Gaza Strip. But that did not end the occupation, because international law defines occupation as the control of territory by an outside force. In the case of Gaza, after the “disengagement” of troops and settlers, Israel remained in complete control of Gaza’s borders, the entry and exit of goods and people, Gaza’s airspace, the sea off Gaza’s coast. Israel prohibited the rebuilding of the Gaza airport, which it had destroyed in 2000, and prevented the construction of a seaport.

The Israeli Jewish community is roughly divided into Ashkenazi, or European, Jews—of whom about one-fifth are Russians who arrived in the 1990s—and Mizrachi Jews. The Mizrachim constitute a wide-ranging category, usually including Jews from Africa and Asia as well as Spain and Latin America. But the majority of the Mizrachim are Arab—they or their forebears emigrated to Israel from Morocco, Yemen, Syria, Egypt, or other Arab countries—or Turkish, Persian, Kurdish, or from elsewhere in the Middle East. Historically there has been significant tension within Israel between Jews of European descent and those whose ancestors come from the Arab world, since Israeli society is heavily racialized and has tended to privilege the Europeans.

About nineteen percent of Israeli citizens are Muslim or Christian Palestinian Arabs.

It was European and Russian Jews, back in the 1880s, who first began significant Jewish immigration to what was then Ottoman Turkish- and later British-ruled Palestine. They came fleeing persecution and violent pogroms, or communal attacks, in czarist Russia and eastern Europe, and they came in answer to mobilizations organized by a movement known as Zionism, which called for all Jews to leave their countries of origin to live in a Jewish state they wanted to create in Palestine. The use of Hebrew, recreated as a modern language in the late 1800s, an orientation toward and identification with Europe and the US rather than the neighboring Middle Eastern countries, and nearly universal military service (excepting only Arabs and ultra-orthodox Jews) became the central anchors around which national consciousness was built.

Israel defines itself as a state of the entire Jewish people, wherever they live, not simply a state for its own citizens. It encourages Jewish immigration through what is known as the Law of Return, under which any Jew born anywhere in the world, with or without pre-existing ties to Israel, has the official right to claim immediate citizenship upon arrival in Israel, and the right to all the privileges of being Jewish in a Jewish state—including state-financed language classes, housing, job placement, medical and welfare benefits, etc. Only Jews automatically have the right to immigrate to Israel; the indigenous Palestinians and their descendants, including those expelled from their homeland in 1947–1948 and 1967, are denied that right, despite the guarantees of UN Resolution 194 (institutionalizing the Palestinian right of return) and those of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights.

Language often gets confusing, and is often used in sloppy ways, both internationally and within Israel itself, where the term “Jews” is often used interchangeably with “Israelis” or sometimes “settlers.” As a result, Palestinians in the occupied territories often fall into the same habit of conflating the terms.

As settler expansion increased, religious and nationalist extremists became a minority among the settlers themselves. Most moved to settlements in the occupied territories because government stipends keep mortgages low, amenities accessible, and commuting to jobs inside Israel easy because of a network of settler-only roads known as “bypass roads,” designed to connect settlements to each other and to Israel without traversing Palestinian towns.

Since 1993, when the Oslo “peace process” began, the settler population has nearly doubled. More than 400,000 Israeli Jewish settlers now live in the occupied territories, 200,000 of them in Arab East Jerusalem. The Jerusalem settlers are particularly problematic, since Israel annexed East Jerusalem after the 1967 war, and while that annexation is not recognized by any other government or the UN, many Israelis deny that East Jerusalem is occupied territory at all.

Settler expansion has continued under both Labor and Likud-led governments. Although Israeli governments have often tried to distinguish between “authorized” and “unauthorized” settlements (distinguishing those officially authorized by the government), in fact all the settlements are in violation of international law. Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention specifically prohibits an occupying power from transferring any part of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies. In fact, international humanitarian law prohibits any permanent change to an occupied land, including imposed demographic changes, that are not intended to benefit the local (occupied) population.

US administrations have identified the settlements variously as “illegal,” as “obstacles to peace,” and as “unhelpful.” But they have consistently accepted Israel’s distinctions between “authorized” and “unauthorized” settlements, calling for the dismantling (and rarely even that) only of the “unauthorized” settlements, as if the older, huge settlement blocs were somehow legal. President George W. Bush called for a settlement freeze in his speech on Middle East policy in April 2002, but has foresworn identifying the settlements as illegal or doing anything to encourage Israel to eliminate the settlements and return the settlers to homes inside Israel.

In 1988, in an enormous, historic compromise, the Palestinian National Council, or parliament-in-exile, voted to accept a two-state solution that would return to Palestinians only the 22 percent of their land that had been occupied in 1967. They accepted that the other 78 percent would remain Israel. While some individual Palestinians and some smaller organizations still reject that historic compromise, for the vast majority of Palestinians the goal is an independent state—a fully realized and truly independent, sovereign, and viable state—encompassing all of the West Bank and Gaza, with East Jerusalem as its capital.

Palestinians also insist on the internationally guaranteed right for refugees to return to the homes from which they were expelled. The right of return is part of international law, and Palestinians are specifically guaranteed that right by UN Resolution 194, which states that “refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return.”

Simply calling for “an end to the violence” is insufficient, because it would leave in place the structures of military occupation that prevent Palestinians from realizing their full national rights and their human rights to dignity, equality, and independence.

Only a minority of Israelis, according to the polls, are committed to holding on to the occupied territories, but the majority, willing to return the territories to the Palestinians and end the occupation, has not been able to influence Israel’s successive governments to do just that. Since the intifada began in September 2000, many Israelis have taken up the view that Palestinian violence can somehow be quashed by ever-increasing use of force, while leaving the occupation intact. Despite its failure so far, a majority still seem to accept or support that position. In the aftermath of the summer 2006 war in Lebanon, the number of Israelis prepared to even consider withdrawal from any part of the West Bank has diminished.

For most Israelis, an end to Palestinian resistance violence would be sufficient, regardless of whether the occupation remained intact.

The 2002 re-occupation of the cities made clear that Oslo’s version of Palestinian “control” was incomplete and thoroughly reversible; Israeli military occupation remained in place, controlling the land and the lives of Palestinians. Israel remains in control of the economic life of Palestine through road and town closures and border controls, and by imposing a complete economic embargo on the Palestinians that began in January 2006. Israel controls Palestinian political life by preventing the Oslo-created Palestinian Authority from meeting, keeping PA officials from meeting or carrying out their responsibilities, and ensuring the PA has no actual power. It controls social life through checkpoints separating cities and villages; by separating families and denying residency permits both in Jerusalem and in the West Bank and Gaza; by denying access to Jerusalem’s, Bethlehem’s, and Hebron’s Muslim and Christian shrines; by preventing access to health and educational institutions, and more.

In the 1990s “yuppie settlers,” uninterested in nationalist or religious rationales and concerned only with the amenities of settler life, became the majority; most indicated they would be willing to give up their homes if they were properly compensated. But increasingly, the minority of ideologically driven settlers, both religious and nationalist extremists, became far more powerful than their numbers, especially within the ranks of the right-wing Likud Bloc. Holding on to the settlements, even the most isolated, became an article of faith and a domestic political necessity for one Israeli government after another. Likud leader General Ariel Sharon himself, speaking before the 2005 Gaza “disengagement,” described Netzarim, a tiny isolated settlement in Gaza, as “the same as Tel Aviv” in importance.

Beyond the politics and the hyperbolic claims of military protection (irrelevant in an era of rockets), the settlements do play one important role in Israeli national life. They allow the diversion of almost all of the West Bank water sources, its underground aquifers, to Israeli settlements and ultimately into Israel itself. Indigenous Palestinians, farmers on parched land and villagers with insufficient water pressure even for a household tap, pay the price for that diversion of water, even as they watch the settlements’ sparkling swimming pools and verdant, sprinkler-watered lawns.

But immediately after the 1967 occupation, Israel began building huge settlements blocs within East Jerusalem, such as French Hill and Pisagot, which were quickly incorporated into Jewish Jerusalem and never acknowledged as settlements. There are now 200,000 Israeli Jews living in East Jerusalem settlements primly defined as “neighborhoods.”

Simultaneously, Palestinian Jerusalemites found their rights severely constrained. Permits for building new houses or additions to over-crowded homes were and remain virtually unobtainable for Palestinians. Marrying a partner from outside the city can put one’s residency permit at risk. Palestinian Arabs in East Jerusalem are considered legal residents of the city—thus they have the right to vote for city council—but are denied full Israeli citizenship.

For many years Israeli officials and many defenders of Israel claimed that the Palestinians who left did so only because they were ordered to by Arab leaders broadcasting on local radio, who allegedly promised them they would be able to return victorious. But throughout the 1990s, an increasingly large number of Israeli academics, the “new historians,” carefully researched and completely debunked that myth. There were no such radio broadcasts. Some of the civilians fled because they were attacked by the Haganah, Palmach, and Irgun militias. Others fled in fear and believed they would eventually be able to come home because it is a longstanding tenet of international law that war-time refugees, regardless of the particular circumstances under which they flee, have the right to return home.

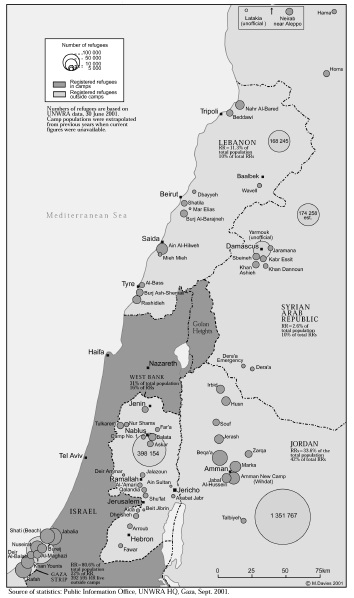

When Palestinians were expelled from their homes in the 1948 war, many fled to neighboring Arab countries, others to the West Bank and Gaza Strip, the parts of Palestine not yet under the control of the new Israeli army. In all those places, corrupt and/or impoverished Arab governments had neither the will nor the resources to care for the sudden influx of refugees. The United Nations, recognizing its responsibility for the crisis through its role in dividing Palestine in the first place, took on the work of caring for the new exiles. It created the United Nations Relief and Work Agency (UNRWA), designed to provide basic housing, food, medical care, and education to the Palestinian refugees until they could return home; UNRWA was initially envisioned as a short-term project. But Israel refused to allow the refugees to return home. Instead, the months turned to years, and tent camps were transformed over time into squalid, crowded mini-towns, made up of concrete block houses with tin roofs held down by old tires and sometimes scraps of iron bars. Electricity remains sporadic, and streams of raw sewage are a common feature between tightly packed houses. But UNRWA schools educated Palestinian children to such an extent that Palestinians today have the highest percentage of college-educated people in the entire Arab world.

Some have claimed that Arab governments have used Palestinian refugees to score propaganda points, or to divert their own people’s anger away from the regimes and toward Israel. Certainly the Arab regimes had little interest in serious political defense of Palestinian rights, let alone serious protection of Palestinian refugees. Only Jordan allowed Palestinians to become citizens. Everywhere else, Palestinians were kept segregated. In Lebanon, they were viewed as a potential disruption to the country’s delicate confessional system balancing Christians and Muslims, and well into the twenty-first century Palestinian refugees in Lebanon remain locked out of dozens of job categories. Egypt kept the Palestinians confined to the Gaza Strip.

But the refugee camps remained in place primarily because Israel blocked the refugees’ right of return, and the Palestinians themselves were determined that they wanted to go home—they did not want to be “integrated” into other Arab countries, despite the common language. Palestinians were— and remain—afraid that leaving the camps to integrate into some other part of the Arab world would result in the loss of their homes and their rights. The Arab world after 1948 was no longer an integrated “Arabia”: nation-states had been created by lines drawn in the sand by colonial powers, as in so many other places in the world. National ties combined with ties to a village or town to create for Palestinians a communal yearning to return home.

At the same time that the United Nations created UNRWA in 1948, it passed Resolution 194, which went beyond customary international law protecting all refugees to provide special protection for the Palestinians. The resolution reaffirmed that Palestinian “refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return.” The UN even made Israel’s own entry to the world body contingent on Israeli acceptance of Resolution 194.

When the West Bank and Gaza were occupied in 1967, many of those living there fled the fighting again, and were made refugees for a second time, finding homes in already overcrowded refugee camps in Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria. There was discussion at the 2000 Camp David summit about allowing some of the 1967 refugees to return to their homes in a future Palestinian state, but no consideration of the right of the refugees who so chose to return to their homes in what is now Israel. Ultimately there was no resolution. (Israel would remain in control of Palestine’s borders, determining who would or would not be allowed to enter the ostensibly “independent” country.)

The 1948 refugees and their descendants, now numbering about five million worldwide, have the right under international law to return to their homes inside what is now Israel. But despite international law and the specific requirements of Resolution 194, Israel has never allowed Palestinian refugees to return to their homes. Israel maintains that allowing the Palestinian refugees to return would change its demographic balance, more than doubling Israel’s current 19 percent Palestinian population. Israelis sometimes use the expression “demographic bomb” to describe the effect of large-scale immigration of Palestinians to Israel. However, international law does not allow a country to violate UN resolutions and international principles in order to protect its ethnic or religious composition. The parallel would be if Rwanda’s new Tutsi-dominated government, after the 1994 genocide, announced that they would not allow the overwhelmingly Hutu refugees who fled during the war to return home, because it would disrupt the new ethnic balance in their country. The United Nations and the world, appropriately, would have made very clear that such a prohibition was unacceptable and that the refugees had to be allowed to return home. Palestinian refugees, despite the passage of time, have the same rights as their Rwandan counterparts.

Most Palestinians recognize that while rights, including the right of return, are absolute, how to implement rights can always be discussed. It is likely that once their right to return has been recognized, some Palestinian refugees may choose options other than permanent return to their mostly demolished villages in what is now Israel. But the key factor will be the ability of individual Palestinians to choose for themselves what to do. Some may choose to go home; some may wish to go only for short visits; some may wish to accept compensation and build new lives in a new Palestinian state; many may choose to accept compensation and citizenship in their place of refuge or in third countries. Some, especially among the most impoverished and disempowered Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon, may indeed choose to return to their homes in Israel. But discussion of how to implement this right of return (in a way that creates the least, rather than the greatest, disruption to Israeli society) cannot begin until Israel acknowledges its responsibility for the refugee crisis, and recognizes the internationally guaranteed right of return as an absolute right.

In the early years the PLO demanded a democratic secular state in all of Palestine—including what was now Israel as well as the 1967 occupied territories. There was no recognition of Israel having the right to exist as a separate Jewish state. But as the shock of the 1967 war and the resulting occupation began to wear off, Palestinians began to broaden their strategic approach. By the mid-’70s, the majority view in the PLO was moving toward acceptance of a two-state solution, an approach already accepted in the UN and elsewhere as reflecting an international consensus. In Israel, where refusal even to consider negotiations with the PLO was the norm, such a shift was viewed as potentially damaging, as it stripped away the key rationale for Israeli antagonism towards all Palestinian claims.

In 1974, the United Nations General Assembly recognized the PLO as the “sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people.” It established November 29 (the day the original partition resolution was signed in 1947) as an International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People, and invited the PLO to participate as an observer within the General Assembly and other UN agencies.

In January 1976, a PLO-drafted resolution backed by a number of Arab countries as well as the Soviet Union was put before the UN Security Council. It called for a two-state solution, Israeli withdrawal to the 1967 borders, and other aspects of the international consensus. Israel refused to participate in the meeting, and the US cast its veto, killing the resolution.

In 1982, the PLO led the joint Lebanese-Palestinian resistance to the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and weeks-long bombardment of Beirut. Soon after, diplomatic efforts led to the organization’s expulsion from Lebanon, with thousands of PLO activists and fighters boarding ships to a new, long exile in Tunis.

Still, the two-state approach remained the majority view within the PLO for some years. In 1988, at the height of the first intifada, it became official when the Palestine National Council convened in Algiers. In a unanimous vote, the PNC proclaimed the “establishment of the State of Palestine on our Palestinian territory with its capital Jerusalem.” Within the political program was official recognition of the two-state approach, despite the fact that the PLO was still an outlawed “terrorist” organization to Israel, and PLO officials were prohibited from even visiting Israel or the occupied territories.

The US opened mid-level diplomatic ties with the PLO a month later, but the organization remained excluded from the US-led international diplomatic efforts. With the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, the PLO’s decision to side with Iraq resulted in intense anger from the oil-rich Gulf countries that had long bankrolled the organization. Palestinians were summarily expelled from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and other Gulf states, and the PLO fell into severe poverty and political isolation in the region.

After the Gulf War, with the PLO at perhaps its weakest point, the US government, flush with its victory over Iraq, approached the PLO to negotiate Palestinian participation in the post-war peace talks in Madrid. The terms were dire—no separate Palestinian delegation, participation only as a sub-set of the Jordanian team, no participation for PLO members, no participation for Palestinian residents of Jerusalem, no role for the United Nations—and the PNC vote approving participation in the Madrid process was bitterly contested. But eventually, the PLO, through its well-known but officially unacknowledged representatives in the occupied territories, accepted. The talks, ostensibly based on UN Resolutions 242 and 338 and the principle of “land for peace,” ground on uneventfully for almost two years, when the surprise announcement hit the press that secret Israeli–PLO talks had been underway in Oslo, and that a Declaration of Principles was about to be signed.

The ceremony on the White House lawn on September 13, 1993, in which President Clinton presided over a handshake between a reluctant Yitzhak Rabin and an eager Yasir Arafat, provided a photo-op of global proportions. A Nobel Prize for Peace, split between Arafat, Rabin, and the Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres, soon followed. The Oslo peace process was born.

Within two years and after extensive negotiations, Oslo’s substantive agreements were signed; their crucial beginnings allowed the return of all the PLO exiles from Tunis to the West Bank and Gaza, where they would be allowed to create a new Palestinian Authority to administer small parts of the still-occupied territories under overall Israeli “security” control.

Beginning in the spring of 2002, as the intifada escalated, Israel moved to re-occupy almost all of Palestine’s major cities, from which its troops had been withdrawn under the terms of Oslo. While Palestinian resistance was fierce in one or two of the cities (Jenin and Nablus in particular), the speed of the Israeli military’s return gave the lie to any notion that Palestinian control, even partial, was designed to be permanent.

Following the withdrawal of Israeli soldiers and settlers from the territory of the Gaza Strip in 2005, the PA was assumed to have full control over Gaza. But Israeli control of Gaza’s borders, as well as Gaza’s entry and exit points, and the lack of any viable connection between Gaza and the West Bank made a mockery of PA authority. After the January 2005 elections, when the Islamist Hamas organization won majority control of the PA, the US and Israel orchestrated a global economic boycott of the PA that made it impossible to govern. By the summer of 2006, with Israel routinely bombing and attacking Gaza’s infrastructure and carrying out “targeted assassinations,” the Israeli military had arrested more than 40 members of the PA’s legislature and about eight members of the cabinet; other PA officials went into hiding or on the run, undermining further any capacity to govern.

Islamist organizations such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad, which have often (though not always) opposed Palestinian diplomatic efforts, have claimed responsibility for most of the suicide bombings. Beginning in early 2002, the secular al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade, which is linked to the mainstream Fatah organization led by Yasir Arafat, began a suicide bombing campaign inside Israel following the assassination of one of its leaders.

Some of the suicide bombings have been directed at military checkpoints or other military targets inside the occupied territories. Others, including some of those with the most serious civilian casualties, involved attacks on cafés, discos, or other public places in Israeli cities. Those targeting civilians are in violation of international law.

The Palestinian Authority, under both Arafat’s and Abbas’s leadership, has repeatedly condemned suicide bombings inside Israel. Perhaps more influentially, leading Palestinian intellectuals and activists in the occupied territories and internationally have also rejected suicide attacks on civilians as a legitimate tactic of resistance, identifying them both as morally unacceptable and politically counterproductive.

People become willing to use their own bodies as weapons when other means are unavailable. Because Palestinians have neither an organized army nor the plethora of F-16s, helicopter gunships, tanks, and armored bulldozers that fill Israel’s arsenal, the bodies of young men and women become weapons instead.

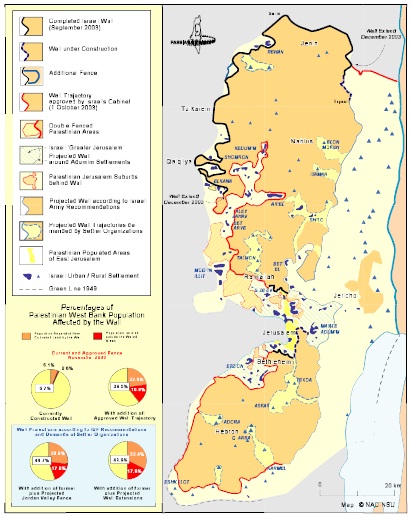

But the Wall was not built to follow the Green Line, as the border between Israel and the West Bank is called; instead it curves significantly eastward in many areas to encompass huge swathes of Palestinian land— settlement blocs, large tracts of Palestinian farmland, and major Palestinian water sources—on the Israeli side. According to the UN, in the Jerusalem area alone, 55,000 Palestinians live in the area between the Green Line and the Wall—an area that in some places will become a closed military zone. Thousands of acres of Palestinian land on both sides of the Wall are being seized by the Israeli military and cleared of houses or farmland. Palestinian farmers are supposed to be allowed to cross the Wall to farm their land, but in many areas the Wall extends for huge distances without access gates. Israeli and Palestinian human rights organizations estimate that when completed, and matched by the planned parallel wall in the Jordan Valley, 90,000 Palestinians will have lost their land.

The Wall completely surrounds the large Palestinian town of Qalqilya in the northern West Bank, separating the town from the West Bank. Besides isolating its population, the effect will also include bringing the valuable Western Aquifer System entirely under Israeli control, since its Palestinian portion lies beneath additional lands to be seized in Qalqilya.

In 2003, Israel announced it would build another wall down the Jordan Valley, thus effectively sealing off a truncated, non-contiguous set of West Bank cantons with impenetrable steel. The result will be to ensure Sharon’s stated goal of allowing a Palestinian “entity” of no more than about 40 percent of the West Bank, in several non-contiguous chunks, plus most of Gaza.

As the Palestinian human rights group LAW points out, under the Fourth Geneva Convention, to which Israel is a signatory, the destruction or seizure of property in occupied territories is forbidden, as is collective punishment. Article 47 outlines that occupying powers must not make changes to property in occupied territories. Seizure of land in occupied territories is prohibited under Article 52 of the Hague Regulations of 1907, which is a part of customary international law. And according to international humanitarian law governing occupation, occupiers cannot make any changes in the status of occupied territories. Israel’s Apartheid Wall seizes land, destroys, and permanently changes the status of occupied territories.

The United Nations estimates that the Wall cuts off at least fifteen percent of West Bank land, and tens of thousands of Palestinians from the West Bank, leaving them on the western, or Israeli, side of the Wall. Significant West Bank aquifers that provide much of the water for Israel’s high-tech agricultural production are also located on Palestinian land that will end up in Israeli hands. Within the Wall-enclosed Palestinian areas, hundreds of Israeli military-run checkpoints remain in place, cutting off most towns and especially smaller villages from each other and from the larger cities that once provided commercial, educational, medical, and cultural facilities. Some towns, such as Qalqilya, are now completely cut off, physically surrounded by the Wall and dependent on the whim of Israeli soldiers, who control the only two gates into the town.

By 2005, Israeli officials (including soon-to-be Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni) had admitted that they intended the route of the Wall to be the basis for the future, unilaterally imposed border of an expanded Israeli state.

Israel rejected the ICJ’s opinion before it was even issued. In January 2004, Israel’s then Prime Minister Ariel Sharon admitted that the Wall was causing problems for ordinary Palestinians, and that the route of the Wall, which cut off huge swathes of West Bank territory, could cause “legal difficulties in defending the state’s position.” But he went on to assert that “there will be no change as a result of Palestinian or UN demands, including those from the [International] court.” Then Justice Minister Yosef Lapid called on his own government to move the Wall, recognizing that “the present route will bring upon us isolation in the world.” But Israel continued construction of the Wall on Palestinian land.

The ICJ also stated directly that other countries have their own responsibility to pressure Israel to comply with the court’s opinion. “All States,” the Court declared, “are under an obligation not to recognize the illegal situation resulting from the construction of the Wall and not to render aid or assistance in maintaining the situation created by such construction.” The US government quietly criticized the Wall early in its process of construction, but soon dropped the critique and agreed, in direct violation of the Court’s ruling on the obligation of other states, to pay Israel almost $50 million—taken out of the $200 million the US provided in humanitarian support to Palestinian NGOs—to construct checkpoints and gates in the Wall.

But “apartheid” refers to a system, not only specific to southern Africa. In 1973, the United Nations General Assembly passed the International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid. The Convention defined the “crime of apartheid” as a crime against humanity, one that was not specific to South Africa. The crime of apartheid is based on racial segregation and discrimination, and included a list of “inhuman acts” that, if committed to establish and maintain domination of one racial group over any other racial group, would result in systematic oppression and be identified as “apartheid.” These acts include murder of the subordinate group’s members; denying its members “the right to life and liberty”; inflicting “serious bodily or mental harm, by the infringement of their freedom or dignity, or by subjecting them to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment”; “arbitrary arrest and illegal imprisonment”; imposing on the group’s members’ “living conditions calculated to cause its or their physical destruction in whole or in part.”

The convention goes on to describe “inhuman acts” that could constitute the crime of apartheid actions that bar the subordinate group’s participation in the “political, social, economic and cultural life of the country, and the deliberate creation of conditions preventing the full development of such a group or groups, in particular by denying to members… basic human rights and freedoms, including the right to work, the right to form recognized trade unions, the right to education, the right to leave and to return to their country, the right to a nationality, the right to freedom of movement and residence, the right to freedom of opinion and expression, and the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.” Other such acts include measures “designed to divide the population… by the creation of separate reserves and ghettos for the members of a racial group or groups, the prohibition of mixed marriages… the expropriation of landed property,” and finally, measures that deprive people and organizations of their “fundamental rights and freedoms because they oppose apartheid.”

Certainly there are significant historical and political differences between the well-known practices of South African apartheid and the system of discrimination against Palestinians that Israel practices. In South Africa the discrimination was based on race, while in Israel the parallel categories are Jew and non-Jew, and there are differences regarding citizenship and other issues. But there are significant parallels as well, both in the histories of South African and Israeli apartheid systems and in the practices themselves. These similarities include laws that divide families, preventing black South Africans or non-Jewish Israelis from owning land, discrimination in education, employment, social services, and more. Further, there is analogous, though clearly not identical, history of earlier pre-state persecution of the dominant group (Afrikaners and Jews), and a comparable form of settler colonialism in both cases, which included the Afrikaner and Zionist settlers themselves turning against their colonial overlords in Britain. One of the most important parallels, though, is the fact that South African apartheid and Israeli apartheid both were and are fundamentally about control of land. The ideologies of racial, national, and religious discrimination were created and imposed to justify the consolidation of power over land and labor. In South Africa, the apartheid government controlled all the land by keeping the non-white labor force under control in urban townships and distant bantustans. In Palestine, the Zionist goal of controlling as much land as possible without Palestinians led to the large-scale expulsions and exiles of 1947–1948 and 1967, and later to the creation of truncated, divided, bantustan-like cantons in the West Bank to allow Israeli control through settlements, a matrix of Jews-only roads and bridges, and annexation of huge swathes of territory.

Some argue that because the term “apartheid” is so fraught with history, so compelling in evoking injustice, that it should not under any circumstances be used against Israel, because Jews were themselves victims of such a great historical injustice in the Holocaust. But criticism of Israel is not the same as criticism of Jews. Israel may define itself as a “Jewish state” or the “state of all the Jews in the world,” but Israel is a powerful, modern nation-state, which must, like any other country, be held accountable both for its accomplishments and for its violations of international law. Many Jews, in Israel, in South Africa, in the US, and elsewhere around the world, reject the claim that Israel speaks for them. They believe that precisely because the term “apartheid” so powerfully describes the effect of Israeli policies on Palestinians, it should become the term of choice to describe the systematic Israeli occupation of Palestinian land and denial of Palestinians’ equal rights.

Throughout his political life Arafat proved far more willing to shift and compromise his position than most international observers gave him credit for. After years of holding to the goal of establishing a democratic, secular state in all of Palestine, he led the PLO to its historic 1988 concession of recognizing Israel and accepting as a goal the creation of a Palestinian state limited to the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem—together comprising only 22 percent of the land of the historic British mandate Palestine. He managed the transition from a liberation movement to a government, despite the challenge posed by the lack of real power or independence for the Palestinian Authority.

And perhaps most importantly, he kept the question of Palestine at the top of the global agenda to a degree unprecedented by any national movement since Vietnam. Arafat went to the United Nations to demand recognition in 1974, and quickly won an observer seat in the global organization for the PLO. And when he declared a putative Palestinian “state” in 1988 in the context of recognizing Israel and accepting a two-state solution, Arafat’s action was quickly followed by a diplomatic initiative that led to full diplomatic relations for Palestine with over 110 countries.

His death followed more than two years of an Israeli-orchestrated and US-backed campaign to isolate and marginalize Arafat in an effort to force even greater political concessions from the Palestinians. During Israel’s spring 2002 offensive, which included massive assaults by ground troops re-occupying most West Bank cities, Arafat’s presidential compound in Ramallah was attacked and largely destroyed by the Israel military. The compound remained besieged for ten days. Although Israeli officials claimed they did not intend to attack Arafat personally, they made clear that if he left the country, he would not be allowed to return. As a result, Arafat spent the next two years in his crumbling compound, leaving only to seek treatment in Paris in the last weeks before his death.

Despite relentless criticism from his own constituents as well as from international leaders, no Palestinian leader ever came close to Arafat’s hold on the emotional loyalty of Palestinians of every political stripe. His last two years focused on ultimately failed efforts to maintain political and organizational coherence among the various PLO and Palestinian Authority security and political agencies, with Arafat’s longstanding goal of leading a truly independent and viable Palestinian state giving way to the reality of presiding over an Authority reduced to squabbling over crumbs of derivative power.

Many world leaders, particularly those in countries that had faced their own struggles for independence from colonial control, issued powerful statements of respect and shared grief at the news of Arafat’s passing. But for Israel, the US, and other powerful countries, pro forma expressions of condolence quickly gave way to barely concealed statements of happiness that Arafat was gone from the scene. Only now, Western leaders claimed, could what was quickly anointed the “post-Arafat era” result in a chance for an Israeli–Palestinian peace—based on the assumption that any “post-Arafat” leader would be even more compliant to US–Israeli demands.

The “road map” was to be implemented by the so-called Quartet, a diplomatic fiction designed to provide political cover to the Bush administration’s unilateral plans for the Middle East by including the European Union, Russia, and the United Nations as part of a team. In fact, the US continued to call the shots, the other three players remained subservient to its plans, and Middle East diplomacy remained stalled. It was particularly unfortunate that the United Nations was coerced into providing political cover to the US through participation in the Quartet, a move that seriously discredited the global organization.

In March 2003, the US, backed by the British, invaded and occupied Iraq; less than two months later the UN Security Council recognized the US and UK as “occupying powers” in Iraq, with all the accompanying obligations under international law.

Under the Fourth Geneva Convention, the Palestinians of the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem, and the people of Iraq all constitute “protected” populations, living under foreign occupations. Throughout its years of occupation since 1967, Israel has engaged in practices that constitute serious violations of international law, including torture, extra-judicial assassinations, extended curfews and closures, house demolitions, the destruction of agricultural land and civilian property, expulsions, illegal imprisonment, and other forms of collective punishment. Even before the US invaded Iraq, the Pentagon and other US government agencies were looking to the Israeli occupation as a model for a future US occupation of Iraq—long before the Bush administration even admitted its plan to invade Iraq. Increasingly, the two occupations have come to resemble each other, as the occupiers have actively collaborated to consolidate their control over angry populations.

In April 2002, more than a year before the US invaded Iraq, Israel sent troops to fully re-occupy the West Bank. The Israeli military’s attack on the Palestinian refugee camp in Jenin led to the killing of dozens of Palestinian civilians, including seven women and nine children. According to Human Rights Watch, “Israeli forces committed serious violations of international humanitarian law, some amounting prima facie to war crimes.” But the US viewed the Jenin attack as a model for its planned invasion of Iraq, and US military officials met with the Israeli military to learn the urban warfare techniques that Israel had used in Jenin. Two years later, in April 2004, the US used those same tactics in the attack on Fallujah in Iraq, including the widespread killing of women and children. In a reversed version of collaboration, Israel admitted using white phosphorous munitions during its 2006 war in Lebanon; the US military has long been condemned for its continued use of this weapon since the Vietnam War.

Further, the torture scandals involving US prisons at Abu Ghraib in Iraq, Guantanamo Bay, and elsewhere reflected many of the same techniques Israel had long used against Palestinian prisoners. The Israeli High Court banned torture in 1999, but the Israeli Public Committee Against Torture indicates that 58 percent of Palestinian detainees report they have been subjected to the same techniques the US troops have used against prisoners in the “global war on terror”: beatings, being forced to remain in painful positions, being hooded for long periods, sleep and toilet deprivation, sexual humiliation, and more. The US general in charge of Abu Ghraib in the first months of the US occupation of Iraq told the BBC that Israeli agents were assisting US interrogators throughout the US-run prison system in Iraq.

The US military certainly did not need Israeli help to occupy another country. But Israel’s years of occupation allowed it to provide the Pentagon with advice and training in tactics designed to take advantage of specific cultural, religious, and national Arab traditions. The US claims that its occupation of Iraq was “democratizing” the entire Middle East was countered by what people on the ground throughout the region actually saw: the expansion of occupations. Instead of new democracy, the US war and occupation in Iraq were viewed throughout the region as a parallel occupation to the US-backed Israeli occupation of Palestine.

By the time of the 2006 Israeli war against Hezbollah and Lebanon, an even clearer connection had emerged. The Israeli goals of attempting to wipe out all resistance to its control and domination of the region matched almost word-for-word the global US goals being fought out in Iraq. In fact, the strategies had similar origins. In the early 1990s, a group of neoconservative American analysts and former policymakers collaborated on a strategic vision for US foreign policy, which became known as the Project for the New American Century, or PNAC. After September 11, many of their ideas gained dominance, being included in the 2002 National Security Strategy document of President George W. Bush, which set the terms for the invasion and occupation of Iraq. But before that, back in 1996, several of the PNAC authors had traveled to Israel at the request of Benjamin Netanyahu, a conservative and US-oriented Israeli politician then running for prime minister. Their strategy paper, called “Making a Clean Break: Defending the Realm,” proposed an almost identical recipe for Israeli foreign policy: focus on military power rather than diplomacy, let all of Israel’s neighbors know that force rather than negotiations would be the new basis for relationships, and make a “clean break” with all earlier peace processes, most notably the Oslo process, then in its third year. When Israel went to war against Lebanon in 2006, many saw the “clean break” strategy coming to bloody life.

The specific threat was that in the regional chaos resulting from the US war in Iraq and its aftermath, Israel might forcibly expel some numbers of Palestinians. But the threat remained even after the initial military attacks on Iraq had given way to US occupation of the country. Perhaps it would be in the form of a punishment against a whole village from which a suicide bomber came. Perhaps 500 or 1,000 or so targeted Palestinian individuals—political leaders, intellectuals, militants, or those Israel claims are militants—would be bused over the river into Jordan or flown over Israel’s border into Lebanon. Besides the massive expulsions that forced more than one million Palestinians into exile during the 1948 and 1967 wars, Israel had relied on “transfer” as recently as 1994. At that time, Israeli troops arrested 415 Islamists from the occupied Palestinian territories, forced them into military helicopters and flew them into the hills of south Lebanon. There, without documents, without permission, and despite rejection by the Lebanese government, they were abandoned on the snow-covered hillsides.

General Sharon himself, elected prime minister of Israel in January 2001, had initially created the “Jordan is Palestine” campaign in 1981–82 that called for expelling all Palestinians out of the occupied territories and pushing them into Jordan. In 1989, former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu told students at Bar-Ilan University: “Israel should have exploited the repression of the demonstrations in China, when world attention was focused on that country, to carry out mass expulsions among the Arabs of the territories.” Recent mobilizations of Israeli academics have issued public calls against “transfer,” but the danger remains very real—2002 polls showed that more than 40 percent of Israelis are in favor of such ethnic cleansing. Advocates of “transfer” have long participated in Israel’s political life. In 2001, Tsomet, a party that officially calls for “transfer,” was given the Ministry of Tourism portfolio in Sharon’s new government. In 2001, and again in 2003, Avigdor Lieberman, the leader of the Yisrael Beitenu party, made up largely of Russian immigrants, who calls openly for forced transfer of Palestinians, was appointed to other cabinet positions. And in 2006, the ostensibly “moderate” government of Ehud Olmert appointed Lieberman as “Minister of Strategic Threats,” with unparalleled authority over dealings with Iran.

In rejecting the Palestinian right of return and accepting the permanence of Israeli occupation of Palestinian land, Bush essentially banished the possibility of achieving a serious and comprehensive solution to the Palestinian–Israeli conflict. The “new status quo” of US-recognized permanent Israeli occupation, no right of return, and no viable Palestinian state, set the terms for the next indefinite period.

The US position accepting Israel’s unilateral decision-making also returned Middle East diplomacy officially to its pre-1991 position, excluding Palestinians from all negotiations. Israeli–US negotiations become the substitute for Israeli–Palestinian talks, with the US free to concede Palestinian land and rights. As one PLO legal advisor told the New York Times, “imagine if Palestinians said, ‘O.K., we give California to Canada.’ Americans should stop wondering why they have so little credibility in the Middle East.”

The US endorsement reaffirmed the US willingness to violate international law, ignore the United Nations Charter, and undermine UN resolutions (including the often-cited Resolution 242, which unequivocally prohibits “the acquisition of territory by force”) to provide diplomatic and political protection for Israel. It even violated the terms of the US-imposed but internationally endorsed “road map,” the first phase of which stipulated that Israel must freeze all settlement activity. Sharon stated explicitly that the six major settlement blocs should continue to grow and be strengthened.

Government officials and commentators from around the world have been unified in condemning Bush’s statements. UN Secretary General Kofi Annan criticized the US endorsement of Israel’s unilateral plan, stating that “final status issues should be determined in negotiations between the parties based on relevant Security Council resolutions.”

Sharon’s “Gaza disengagement” plan was part of a strategy to end Israeli–Palestinian negotiations. Sharon made clear that he viewed the pull-back of troops and settlers as part of a “long-term interim solution,” in which Israeli occupation would be retooled to remain in place virtually forever, without ever reaching “final status” negotiations. That meant giving up the Gaza settlements and shifting the military control of Gaza, at least until the re-occupation that occurred in July 2006, from inside its cities and towns to positions surrounding and controlling it from outside.

The Gaza settlements, while economically valuable for Israel (not surprising given that the 8,000 settlers controlled 40 percent of the land and 40 percent of the water of the 1.4 million Palestinian residents of the Gaza Strip) were still costly, because the small number of settlers depended on significant numbers of Israeli troops for protection. So giving up the Gaza settlements was a small price to pay for consolidating Israeli control over the much more valuable land of the West Bank, and guaranteeing permanent US support for Israeli annexation of the huge West Bank settlement blocs and even more land encompassed within the Apartheid Wall.

This strategy of giving up Gaza settlements to annex West Bank land became known as the “convergence plan” when Ehud Olmert took over as prime minister in March 2006, after the incurable stroke that three months earlier ended the political career of Ariel Sharon. Following Israel’s serious defeat in the Lebanon war that summer, Olmert’s Sharon-linked popularity quickly declined, and his plan to evacuate some tens of thousands of West Bank settlers, while leaving 80 percent of the 240,000 settlers in place, evaporated. Israelis no longer seemed willing to envision even a small-scale symbolic withdrawal to provide political cover to the much larger-scale annexation of prime Palestinian land. Instead, a potentially indefinite continuation of the unstable status quo loomed.

Throughout its years, Hamas’s activities have always been far broader than those of its well-known military wing. Especially in Gaza, always the poorest part of Palestine, Hamas created a widespread network of social welfare agencies, including schools, clinics, hospitals, mosques, and more. During the years of the first intifada (1987–1993), as well as the years of the Oslo process and the Palestinian Authority (from 1993 on), Hamas provided many of the basic services that Israel as the occupying power refused to provide, and that the PA, lacking real power and facing both poverty and problems of corruption, could not. As a result, Hamas’s popularity grew.

Hamas’s first suicide bombing was in 1993, and for many in Israel and internationally, that method of attack came to characterize the organization. Some of the attacks were against Israeli soldiers in the occupied territories—acts of military resistance authorized under international law—but others targeted civilians inside Israel itself, in violation of international law. Hamas declared a unilateral cease-fire in March 2005, which it maintained until June 2006, when it announced its intention to break the cease-fire in response to a continuing and then escalating set of Israeli attacks. Of particular relevance in the Hamas decision was the Israeli attack just days before on a Gaza beach that killed nine Palestinians, seven of them from one family, including five children. The end of the cease-fire led to Hamas’s attack on an Israeli military patrol just over the Gaza border, culminating in the capture of one Israeli soldier.

Israel has targeted many Hamas leaders for assassination, including Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, the paralyzed and wheelchair-bound founder and spiritual leader of Hamas, who was killed by an Israeli missile in Gaza in March 2004. His position was taken over by Abdel Aziz Rantisi, who was killed by Israel a month later. Rantisi, a Gaza physician, was among the 400 Hamas activists kidnapped by Israel and expelled to Lebanon in the early 1990s. Returned to Gaza in a prisoner exchange, Rantisi was assassinated by a “targeted” Israeli missile strike in Gaza. In another ostensibly “targeted” assassination, this time of Hamas leader Salah Shihadeh, fourteen other people, nine of them children, were killed by the Israeli military air strike. State Department officials reportedly attempted to warn then Secretary of State Colin Powell about Israel possibly violating the US Arms Export Control Act through its use of US-provided weapons in the assassination. But according to US News and World Report, then Undersecretary of State and later US Ambassador to the United Nations John Bolton prevented the warning from being passed on to Powell.

International observers, including US government officials and mainstream media, often misrepresented Hamas’s political stance, which changed in response to political developments over the years. For years, Hamas had rejected a two-state solution, holding out for what it called an Islamic state in all of historic Palestine. But the Palestinian majority that elected Hamas in January 2006 included many who did not endorse that program. And in the midst of the summer 2006 Israeli attacks on Gaza, Hamas leader and Palestinian Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh wrote in the Washington Post that the Gaza crisis was part of a “wider national conflict that can be resolved only by addressing the full dimensions of Palestinian national rights in an integrated manner. This means statehood for the West Bank and Gaza, a capital in Arab East Jerusalem, and resolving the 1948 Palestinian refugee issue fairly, on the basis of international legitimacy and established law.” That carefully articulated set of Palestinian goals—clearly “moderate” even by US and European standards— matched closely what Haniyeh called Palestinian “priorities.” Those included “recognition of the core dispute over the land of historical Palestine and the rights of all its people; resolution of the refugee issue from 1948; reclaiming all lands occupied in 1967; and stopping Israeli attacks, assassinations and military expansion.” It was significant that the Hamas leader, often accused of calling for “the destruction of Israel,” actually distinguished between the need to “recognize” all the lost lands and rights of pre-1948 historical Palestine and the need for Palestinians to “reclaim” only those lands occupied in 1967.

There are strong indications that huge turn-out for Hamas was not really a statement of support for an Islamist social agenda or for their prior military attacks (Hamas had initiated and maintained its own unilateral cease-fire from early 2005). Rather, it was a call for change in the Palestinians’ untenable situation, rejecting the status quo. In his report immediately after the election, Carter recognized that “Fatah, the party of Arafat and Abbas, has become vulnerable because of its political ineffectiveness and alleged corruption.” At the time, many Palestinians said that they could have accepted the existing leadership even with its corruption, if only Fatah had any success in ending the occupation, and could have accepted its political failures if only it were not so corrupt. But the combination of corruption and failure was simply too much, and Hamas reaped the electoral results.

Israeli leaders immediately responded with claims that they now had “no partner for peace,” stated that they would not negotiate with a Hamas-led Palestinian Authority, and called for an international boycott of the new government. But those claims were a red herring—Israel had not been negotiating with the existing (Fatah-led, non-Hamas) Palestinian Authority for more than two years, having chosen instead a strategy of unilateral action to redraw borders and impose an Israeli “solution” to the conflict.

The US, having already accepted the unilateral, no negotiations approach of then Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, including Israel’s abandonment of the US backed “road map,” also promoted the Israeli call for an international boycott and sanctions against the Palestinians. And it was US pressure on Europe, Arab states, and many other US allies to accept the boycott that was largely responsible for the humanitarian crisis that soon hit the occupied territories, especially Gaza. For example, when some Arab banks announced plans to transmit humanitarian assistance donated to beleaguered Palestinians, the US announced that the US branches of those banks would face serious sanctions. Not surprisingly, the banks withdrew their plans, and the Palestinians did not get the funds.

The result was a dramatic rise in the already dangerous humanitarian crisis. In a rare joint statement in July 2006, UN agencies stated that they were “alarmed by developments on the ground, which have seen innocent civilians, including children, killed, brought increased misery to hundreds of thousands of people, and which will wreak far-reaching harm on Palestinian society. An already alarming situation in Gaza, with poverty rates at nearly eighty percent and unemployment at nearly forty percent, is likely to deteriorate rapidly, unless immediate and urgent action is taken.” The UN’s overall coordinating body, OCHA (Office for Coordinating Humanitarian Assistance), called on Israel to allow UN deliveries of emergency supplies, but recognized that “humanitarian assistance is not enough to prevent suffering. With the [Israeli] bombing of the [Gaza] electric plant, the lives of 1.4 million people, almost half of them children, worsened overnight. The Government of Israel should repair the damage done to the power station. Obligations under international humanitarian law, applying to both parties, include preventing harm to civilians and destroying civilian infrastructure and also refraining from collective measures, intimidation and reprisals. Civilians are disproportionately paying the price of this conflict.”

The term “targeted assassination” is designed to disguise two huge problems. First, the “targeting” is not so precise. According to the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem, of 331 Palestinians killed in “targeted assassination” operations between September 2000 and June 2006, 127 were not targets at all; many of them were women and children. Second, calling these killings “targeted” does not make them legal; the Fourth Geneva Convention prohibits all killings by the occupying power of anyone in the occupied population. There are no exceptions.

Most of the assassinations are carried out long-distance—using missiles, rockets, or bombs that hit cars or houses or whole residential neighborhoods. In 2002, the killing of Hamas leader Sheikh Salah Shihadeh at 3AM in a crowded Gaza apartment building resulted in not only his death but also the deaths of fourteen others, including nine children. Four years later, Israel’s implementation of the assassination policy escalated again, following the Hamas victory in the Palestinian elections. In response, the Public Committee Against Torture in Israel noted that the problem of people being killed who were not the “official” target was made “abundantly clear during the 7 February 2006 air strike [in Gaza] that killed the two targeted people but also injured four children, one critically.” A few months after that attack, on July 12, another Israeli air assault on a Gaza house, missed the “targeted” Hamas leader, but did kill two other adults and seven children.

The Fourth Geneva Convention, under Article 3 (1) (a) prohibits all “violence to life and person” and “murder of all kinds.” Giving murder the clinical term “targeted assassination” does not make it legal. Israel has attempted to disguise the clear illegality of these killings by asserting that each is individually approved by the Prime Minister; but in fact, the authorization by any Israeli official, or even by Israel’s highest courts, is thoroughly irrelevant as a defense to the Geneva Convention’s absolute prohibition.

The carefully planned removal of Gaza settlers in the summer of 2005 showed a powerful picture of grieving families being forcibly—if gently—removed from their homes. Israel offered each settler family hundreds of thousands of dollars in compensation, and new homes were quickly made available in Israeli towns or, ironically, in equally illegal West Bank settlements. Groups of settler families wishing to remain together were assured of neighboring homes wherever they wished to move. It was a humane response to the inevitably sad human cost of forcible relocation (although all the settlers knew they were living on occupied territory in violation of international law). And it was a far cry from the fifteen-minute get-out-with-whatever-you-can-carry warnings in most, and the complete lack of compensation in all, of Israel’s expulsions and house demolitions of Palestinians throughout the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza Strip.

Following the Israeli redeployment, Gaza’s territory was free of Israeli soldiers and settlers, but remained surrounded and under complete Israeli control: Israel continued to control Gaza’s economy, withholding $50 million or so of Palestinian monthly tax revenues, prohibiting Palestinian workers from entering Israel, and controlling the Israeli and Egyptian border crossings into and out of Gaza for all goods and people. Israel forcibly limited the range of Gaza’s fleet of fishermen. It controlled Gaza’s airspace and coastal waters, and continued to prohibit construction of a seaport or rebuilding the airport. And after the election of the Hamas-led government in January 2006, Israel continued its air strikes and ground attacks on people and infrastructure throughout Gaza, and its almost nightly barrage of sonic sound-bombs across Gaza’s population centers. Under international law, such a siege constitutes a continuation of occupation.

Conditions in Gaza rapidly deteriorated; by early 2006 UN and other humanitarian agencies were reporting widespread hunger; unemployment spiked over 60 percent in many areas, and long-term Israeli closures of the border crossings meant virtually no Gazan produce could reach the market. The rate of absolute poverty—of people living on less than $2 per day—rose to 78 percent, an unprecedented level.

In June 2006, Israel responded to a border skirmish in which an Israeli soldier was captured, with a full-scale armed assault on Gaza, including air, sea, and ground attacks. Israeli commandos carried out midnight raids in Gaza (as well as many West Bank cities) to kidnap Hamas legislators and Cabinet ministers of the Palestinian Authority. The New York Times quoted Prime Minister Ehud Olmert saying that despite the earlier claims of “disengagement,” Israel would continue to act militarily in Gaza as it wished, “We will operate, enter, and pull out as needed.”

In January 2006 the Palestinian Authority held elections. The Islamist organization Hamas won a majority of votes (see page 65). In response to the election of Hamas, internationally recognized as fair, the US backed Israel’s call for an international boycott and sanctions against the elected government, cutting all financial aid, punishing banks that might allow transfer of funds, and isolating the Palestinian Authority. Throughout the spring of 2006, conditions deteriorated across the occupied territories, with impoverished Gaza the worst hit. Unemployment in Gaza hovered near 70 percent, and poverty rates climbed to almost 80 percent. UN officials feared a humanitarian crisis. Israel continued its arrests and “targeted assassinations,” and in June a family of seven, including five children, was killed by Israel’s shelling of a Gaza beach. In response to the escalating Israeli attacks, the ongoing economic boycott, and the skyrocketing humanitarian crisis, Hamas called off its then–sixteen-month-long unilateral cease-fire. The capture of the Israeli soldier followed two weeks later. In early July 2006, the Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz reported that Israel’s attorney general had acknowledged that the plan to send troops back into Gaza had been decided weeks earlier. (Also in July, while the Israeli assault on Lebanon was underway, both Ha’aretz and the San Francisco Chronicle reported that the Israeli military’s war plan for Lebanon had been in the works for two to four years, with officials waiting for the opportune moment to launch the attack.)

The war that Israel launched against Gaza in June 2006 and against Lebanon weeks later began when Israel chose to escalate border skirmishes to full-scale wars against civilian populations. Hamas attacked a military post just over the Gaza border—an act of resistance to occupation considered legal under international law since it was against a military, not civilian target. Similarly, Hezbollah’s July 12 raid across the Israeli border may have violated the 1949 armistice agreement between the newly created state of Israel and Lebanon (there was never a peace treaty between them), but the raid was limited to a military target.

As Human Rights Watch described it, “the targeting and capture of enemy soldiers is allowed under international humanitarian law.” In both cases Israel responded first with cross-border raids of their own to try to get its captured soldiers back, legal under international law. But, it was Israel that then took the step of escalating from a small-scale border skirmish into full-scale war—by immediately launching major attacks against civilian targets. Israel destroyed the only power plant in Gaza, plunging 800,000 Gaza residents into months of hot, thirsty darkness at the height of the desert summer. In Lebanon, Israel began by attacking key bridges linking towns in southern Lebanon and destroying the international airport, before escalating further to fullscale assaults on the total infrastructure and civilian population of southern Lebanon, and much of Beirut and the rest of the country.