Equality means both within and between states. Israel and Palestine, as equals, would jointly exchange full diplomatic relations. Israeli settlers would be disarmed and given the option of moving to new homes inside Israel, or remaining in their homes as citizens of Palestine with no special privileges and accountable to the Palestinian government. Jerusalem would be an open city, with two separate capitals within it: the capital of Israel in West Jerusalem, and the capital of Palestine in East Jerusalem.

A comprehensive peace would also include recognition of the right of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes. That starts with Israel’s recognition of its role in the expulsion of refugees and creation of the refugee crisis in 1948, and public acceptance of Resolution 194 and the legal right of refugees to return, to which Israel agreed at the time it joined the United Nations in 1949. Once the right to return has been recognized, discussions about how best to implement it can begin.

Each state would be responsible for maintaining the safety and security of its own citizens, and would make commitments to prevent any cross-border attacks on civilians in the other’s territory.

A comprehensive and lasting peace will also require economic arrangements that move quickly to reverse the humanitarian disaster currently prevailing among Palestinians, as well as addressing the vast disparity of economic power between the two countries. Technology transfer and job creation should be among the approaches considered.

Within each state, equality of all citizens would be guaranteed; there would be no privileges for Jews or discrimination against non-Jews in Israel, and none of the reverse in Palestine.

The issue of the personal safety of individual Israelis is different. During the years of Israel’s occupation of Palestine, resistance to that occupation has sometimes taken illegal forms, including attacks on civilians inside Israel. But the overwhelming majority of attacks on civilians—terrorist attacks— however illegal, were in fact waged in response to Israel’s occupation; with the end of occupation, the overwhelming majority of attacks will end. Certainly both Israel and Palestine will have an obligation to protect their own citizens from cross-border (or internal) terrorist attacks. When a fully independent and sovereign Palestinian state can develop normal relations of equality with Israel, as opposed to the distorted relationship of occupied and occupier, it will be possible to cooperate on security issues as well.

An end to Israel’s occupation will immediately reduce tensions and instability in the region. The establishment of an independent Palestinian state and its normalization of relations with Israel as well as with surrounding Arab states will set the terms for the other Arab states’ normalization of ties with Israel, further easing tensions in the Middle East. Certainly, many problems will remain; Israel’s economy is many times larger than that of the surrounding Arab states, setting the threat of increasing inequity as the basis for regional economic cooperation. The “new Middle East” might look unfortunately similar to the “new North America,” in which free trade agreements end up further enriching the US behemoth, while the much smaller Canadian and especially the far poorer Mexican economy pay the price.

But such developments are not inevitable. The potential remains for democratization and efforts for regional advancement as the trajectory of the next century. But all of that must wait until an end to Israel’s occupation. And because anger at Israel’s occupation translated so powerfully into anger toward the US, Israel’s global patron, an end to occupation will also reduce antagonism toward US policies and indeed reduce the threat to ordinary Americans that those policies engender.

Throughout history, longstanding injustices sometimes become permanent. They do not become just or fair because time passes or power consolidates, but some of their results endure. The massive dispossession and genocide that led to the near-extermination of Native Americans is no less unjust 400 years later. But while in 1607 it might have been legitimate to advocate the justice of sending all the European colonists back to Europe and returning all the land to the Native Americans, in 2007 the search for justice, while continuing, is very different. Human rights in the form of national recognition, treaty rights, economic reparations, affirmative action, protection of remaining tribal-held lands, and more are the new demands of Native Americans.

Certainly the Palestinian case is different. At the beginning of the 21st century, the Palestinian al-Nakba, or catastrophe, the 1948 war in which Palestinians were dispossessed from their land, was just over fifty years past. Many older Palestinians still remember fleeing their homes and still hold keys to the doors they have long imagined re-entering. Justice requires first that Israel acknowledge the truth of its responsibility for that dispossession and for denying the refugees their right to return. There must be an effort to recognize the legitimacy of international law, to restore lost lands and human rights, including the right of self determination.

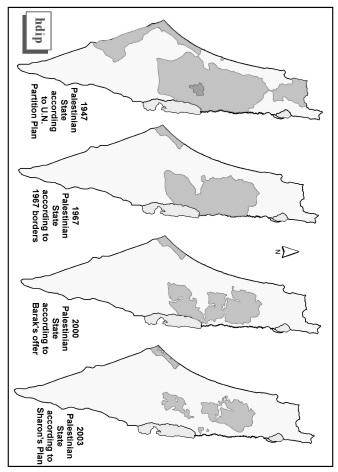

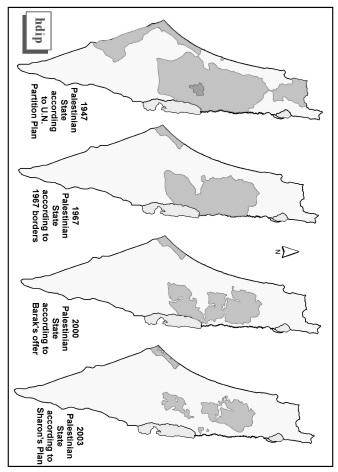

The search for justice for Palestinians, so long denied their human and national rights, continues. The goals of ending occupation and establishing equal rights for all, based on international law and human rights, remain absolute. Many believe those goals can best be achieved through creation of an independent, viable, and sovereign State of Palestine in the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem. Such a solution—if based on the 1967 borders and including the complete withdrawal of soldiers and settlers not only from Palestinian territory but also from control over the new state’s borders, realizing the right of return for Palestinian refugees, and ensuring equal rights and equal security for all Palestinians and Israelis both within and between the two states—would indeed be a huge accomplishment in the struggle for human rights and justice.

But as the construction of the Apartheid Wall and the continued expansion of the 440,000 settlers in huge city-sized settlements throughout the West Bank and East Jerusalem seem to make the creation of a viable Palestinian state impossible, more and more Palestinians are reconsidering the goal of creating a democratic secular or bi-national state in all of historic Palestine – encompassing what is now Israel, the West Bank, Gaza, and Jerusalem. Many, perhaps most Palestinians and at least a few Israelis, believe that over the long-term it is in the best interests of both peoples, even if there were an independent and sovereign Palestinian state, to create a single state, based on absolute equality for both nationalities and equal rights for all its citizens.

Certainly such an approach could only result from a free and open choice by both Israelis and Palestinians. Considering such an option is for the future; it will not likely reach the serious discussion stage until Israel and Palestine, and thus Israelis and Palestinians, can sit across a negotiating table as equals, not while they face each other, as today, as occupied and occupier. But the search for justice, in all its various forms, must continue.