Chapter Six

Connors v. United States and Cheyenne Indians:

Were the Indian Wars Legal?

THE LAND CAN SPEAK to those who listen. The stories it tells are not always pretty. There is a bluff near Chivington, Colorado, overlooking Big Sandy Creek where you can hear women and children crying in the wind. This remote spot is the place where 160 Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians were murdered by Colonel John M. Chivington’s militiamen. The dead were horribly mutilated. Afterward, their scalps and body parts, including genitalia and fetuses, were paraded about Denver by the troops as grisly trophies before cheering crowds. Skulls of decapitated victims were sent back East to the Smithsonian Institution. In Indian Country, the Sand Creek Massacre created shock waves of anger among the Plains Indian tribes, because the Cheyenne and Arapaho villagers were mainly unarmed women, children, and the elderly who were at peace. They were camping at the site under the protection of the US flag when the unprovoked surprise attack took place. Subsequent government investigations determined that the assault was unauthorized, but no one was ever punished, not even a sacrificial corporal.

The 1864 massacre cut deep wounds into fragile race relations on the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain region, prompting bloody retaliation between Indians and whites for years to come. Only recently have those wounds begun to heal. Today, this haunting place lies peacefully hidden among the sand hills and grasslands of southeastern Colorado, populated mainly by antelope, coyote, and prairie dogs. It is hard to imagine the terror of that day, among the cottonwood timbers in the valley below the bluffs, where howitzers fired down into the village. In 2007, the US Park Service and Cheyenne Nation officially dedicated this place as the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site before a large crowd of descendants, dignitaries, and onlookers who gathered to pay tribute to the dead and memorialize this tragic episode in American history. One tribal speaker observed, “They say the event of Virginia Tech was the deadliest shooting rampage in American history. I think this was the deadliest shooting rampage in American history.”

I have always admired the Cheyenne people. Over the years, I have enjoyed many friends, relatives, and clients among this fabled tribe.1 In many respects, the Cheyenne Indians are American icons. Their history, way of life, value system, and spiritual outlook provide a rich example of Plains Indian culture. For many people around the world, their striking images, proudly adorned in beautifully beaded buckskin and regal eagle-feather warbonnets, transcend the art of one tribe and symbolize the heart and soul of Native America itself. The history of my own people, the Pawnee Indians, is closely intertwined with that of our Cheyenne neighbors.2 They call themselves Tsis tsis’ tas, meaning the “Human Beings.” Our Pawnee name for them is Sahi, and they are referred to in sign language as “Cut Fingers,” after their mourning practice of making flesh offerings upon the death of a loved one. Though our two tribes were once traditional enemies who competed for hegemony over buffalo hunting grounds in the headwater country of the Republican River valley, each regarded the other as a brave people, and our numerous epic encounters are recorded in song,3 stories,4 buffalo hide paintings, and ledger book drawings.5

Violence often follows when two proud peoples collide. The Cut Fingers refused to bend when confronted by the warlike Americans, who are called Reesi Kutsu’ (“Big Knives”) by the Pawnee. The Human Beings steadfastly opposed the Big Knife incursion into the Great Plains. With only four thousand tribal members in 1875, they engaged the army in at least eighty-nine fights.6 Their homeland is filled with haunting places where they fought and died—along the far-flung banks of the Washita, Sappa, Platte, Little Bighorn, Arikaree, and Republican rivers, in the Red Fork valley of the Powder River, at the Summit Springs refuge hidden deep within the Great Plains, and killing grounds like the infamous Sand Creek site and Fort Robinson stockade. In the end, the Cheyenne Nation settled on two reservations in Oklahoma and Montana—like other Plains Indian tribes dispossessed of their aboriginal lands by various means and placed onto the reserves that dot the American heartland.

During the nineteenth century, warfare was virtually constant for nearly fifty years on the Great Plains, where the resolve and warlike prowess of the indigenous peoples matched that of the Big Knives. At the height of the Indian wars, white fighters fervently longed to exterminate the Indian race altogether. “Nits breed lice,” according to Colonel John M. Chivington, the fighting preacher who led the grisly Sand Creek Massacre in 1864.7 As General William Tecumseh Sherman remarked in 1869, “the only good Indians I ever saw were dead.”

What was the legal basis for the Indian wars? This subject has largely been ignored by scholars. In our legalistic nation, even something as brutal as war must be done in accordance with the law. Despite its medieval Christian origins, the law of war is part of the dark side of the law, because it legitimizes naked violence, invasion, and conquest. This chapter explores the legal basis for the use of force against Native Americans in the Indian wars. Interestingly, no case squarely addresses the issue. In Connors v. US and the Cheyenne Indians (1898), the court examined the facts surrounding the extermination of Cheyenne exiles led by Morning Star and Little Wolf during their epic fifteen-hundred-mile exodus in 1878–79.8 Unfortunately, the court did not address the legality of those killings.

Connors is included as one of the ten worst Indian law cases ever decided, not because of its outcome, which is favorable to the Indians, or its legal precedent, but because the fact that it had to be decided at all illustrates larger problems in the law that warrant discussion. One cannot read the opinion without being overwhelmed by the grave subject matter addressed by the court on several levels. First, Connors draws attention to the need to confront and clarify the far-fetched notion of “conquest” in federal Indian law. Exactly what is the law of conquest and how has it shaped federal Indian law? A second problem arises on the international level. Is there an unspoken double standard in the law of war that allows settler states to wage war against indigenous peoples without observing the limitations and protections secured by the law of nations? Above all, the horrific facts etched in Connors’s evidentiary record raise a much larger, heartbreaking human-rights question: were the Indian wars legal? The answer to this question is significant. If those conflicts were authorized by law, then the killing and destruction were perfectly legal acts of war. If not, it was murder.

In exploring the role of law and judicial tribunals in the Indian wars, we will begin by examining the notion of conquest in federal Indian law, then describe the law of war that was applicable to the Indian wars, using an actual military conflict between the United States and the Northern Cheyenne as a case study. From this exploration, legal standards will emerge for judging the use of force against Native people in the United States.

The Notion of Conquest in Federal Indian Law

Conquest is not normally considered to be a legitimate source of governmental power in a democracy. Democracies rely instead upon constitutional law to govern their citizenry and to guide relationships with their political subdivisions. Yet unlike any other segment of society in the United States, Native America is subject to the extraconstitutional law of conquest. The Supreme Court has relied upon doctrines of conquest to divest Indian tribes of title to their land and to uphold government extinguishment of aboriginal title, confiscation of aboriginal land, and laws that exercise dominion over Indian peoples and their property. This is an anomalous situation because everyone else is governed by the powers invested in federal and state government by the Constitution.

In this sense, Native Americans are excluded from the ideas of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke in Western political theory that the power to govern is derived from the consent of the governed or of individuals who entered into a social contract, as society emerged from anarchy, to be governed for the common good. Under this theoretical basis of democracy, non-Indians are subject to the power of government by virtue of their citizenship or, in the case of immigrants, their place of residence, and the government exercises authority over them pursuant to ordinary civil and police powers found in the Constitution. Likewise, political subdivisions, like states, have social contracts by which they voluntarily joined the union—either when the Constitution was formed or later, by democratic processes. No one suggests that by coming into the union, the fifty states were conquered (except perhaps the State of Hawaii), or that states or their citizens must be ruled under principles of conquest. It is only Indian tribes and their members who live under that supposed basis for governance.

This anomalous situation prompts a string of questions. What is this notion of conquest all about? What is the factual and legal basis for the doctrine of conquest in federal Indian law? Were Indian nations really conquered, and if so, when and how? Is it legally or politically necessary (or desirable) for the United States to rely on bare conquest to govern Indian tribes, rule Indian people, and exercise dominion over their property? Finally, if Native America was never really conquered, what were the Indian wars all about?

We will explore these questions briefly to provide a backdrop for considering the law pertaining to the Indian wars. As you will see, the notion of conquest is embedded in federal Indian law, but it rests on flaky legal grounds—a legal fiction articulated in Johnson v. M’Intosh (1823) and then rejected by the same court in Worcester v. Georgia (1832)—and on shaky factual grounds, if we apply the commonplace definition of conquest to the facts at hand. Furthermore, there is no apparent need for the United States to rely upon conquest in its relations with the tribal governments that exist within its territory, to control Native Americans or exercise power over their property. Ample power over Indian affairs is provided by a far more legitimate source: the US Constitution. As such, the doctrine of conquest is superfluous and should be expunged from federal Indian law as an outmoded and injurious vestige of our colonial past.

Talk of conquest started early. It began in the courts with Johnson v. M’Intosh (1823), when John Marshall crafted the rules for acquiring Indian land under the doctrine of discovery. According to Johnson, the multipurpose doctrine did several things. It operated to vest legal title to Indian lands in the United States; it granted the United States limited sovereignty over Indian nations; and it empowered the government to obtain Indian land by purchase or conquest.9 Purchase is a straightforward concept. Indeed, nearly every aboriginal acre acquired by the United States was purchased through treaties made during times of peace—sometimes fair and square, often by hook or crook.10 But conquest is an ugly word. It conveys a darker, more menacing connotation that requires greater explication. After all, conquest is aggression in its worst form.

Marshall wrote in Johnson that “title by conquest is acquired and maintained by force” and the “conqueror prescribes its limits.”11 This rule flew in the face of international law of the era, since bare conquest has never been considered sufficient to convey good title under international law. The law of nations has always forbade the use of force simply to acquire territory. Thus, Marshall was forced to devise a creative exception to the rule that conquerors must respect property rights in the lands they invade (i.e., we do not own Iraq merely because we invaded that nation). He said that the normal rules of international law governing the relations between the conqueror and conquered are “incapable of application” in the United States. Why? Because the settler state was confronted by Indian nations composed of “fierce savages, whose occupation was war.” He therefore considered it impossible to mingle with Indians, to incorporate them into a colonial social structure, or to govern an Indian nation as a distinct people, because the Indian nations “were ready to repel by arms every attempt on their independence.” Thus, “frequent and bloody wars, in which the whites were not always the aggressors, unavoidably ensued.” According to Marshall, these factors forced the settler state to “resort to some new and different rule, better adapted to the actual state of things.” The new rule fashioned in Johnson was an outlandish legal fiction that converted “discovery of an inhabited country into conquest.”12 Even if it looked good on paper, Marshall’s new rule meant nothing to Indian nations. It was a paper conquest by the Supreme Court in name only. The United States’ extravagant legal claims to land and sovereignty over any unwilling Indian nations remained to be won the hard way—“by the sword.”13

Following Johnson’s discourse on conquest, Indian law opinions quickly began to fill with metaphors of war.14 The early opinions were written during wartime with an unmistakable military mind-set, sometimes by judges who were themselves veterans of military conflicts with Indian tribes. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), Justice Thomas Johnson reiterated that discovery grants rights of dominion over the country discovered, and that conquest provides such rights in case of war. He described Georgia’s assertion of legal rights against the Cherokee Nation as “war in disguise.”15 The southern judiciary wrote jingoistic opinions in the extension cases discussed in chapter five that drip with hostility against Indians.16 By 1955, the myth of conquest was so prevalent in the law that the Supreme Court assumed every American Indian and Alaska Native tribe had been conquered, even though few actually lost their land or independence by force of American arms. Justice Stanley Reed stated in Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v. United States (1955):

Every American schoolboy knows that the savage tribes of this continent were deprived of their ancestral ranges by force and that, even when the Indians ceded millions of acres by treaty in return for blankets, food, and trinkets, it was not a sale but the conqueror’s will that deprived them of their land.17

The legal and factual basis for the doctrine of conquest rests on dubious ground. One can argue that the Indian tribes were conquered and are subject to the law of conquest, because (1) Johnson says discovery by Europeans means all Indian tribes are automatically conquered; (2) Indian nations lost their independence and sovereignty by force of arms or they became domestic dependent nations through treaties; and (3) the territories of Indian nations were appropriated by the United States in war. An examination of each argument shows that none hold water, except in rare instances.

First of all, conquest cannot be equated with discovery. A legal fiction is an assumption of fact made by a court as the basis for deciding a legal question. The legal fiction used in Johnson bore no relation to reality in 1492 or 1823, when the case was decided—it was simply not true. Importantly, that legal fiction was at issue and rejected in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), when the Supreme Court discarded the absurd ideas about conquest and dominion found in the doctrine of discovery:

This soil was occupied by numerous and warlike nations, equally willing and able to defend their possessions. The extravagant and absurd idea, that the feeble settlements made on the sea coast, or the companies under whom they were made, acquired legitimate power by them to govern the people, occupy the lands from sea to sea, did not enter the mind of any man.18

Unjust legal fictions in the law that are wrong and injurious should be rejected, not perpetuated by modern courts. Just like the legal fictions used in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) that blacks are racially inferior and segregation is not harmful or denigrating were finally rejected in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), it is time to retire the foolish legal fiction that European discovery of an inhabited continent can be equated with the conquest of that continent.19 Whether conquest occurred is best determined on a case-by-case basis, rather than by a sweeping assumption.

Second, the domestic dependant nation status of Indian tribes is not considered conquest when it is established through treaty agreements. When Worcester put flesh on that political classification, the court explained that treaty agreements placing Indian nations under US protection do not conquer or deprive them of their sovereignty, because “[p]rotection does not imply destruction of the protected.”20 The protectorate relationship is frequently found in international relations. It is simply one “nation claiming and receiving the protection of one more powerful: not that of individuals abandoning their national character, and submitting as subjects to the laws of a master.”21 Worcester emphasized that “the settled doctrine of the law of nations is, that a weaker power does not surrender its independence—its right to self government, by associating with a stronger, and taking its protection.”22 Furthermore, the Indian protectorate relationship described in Worcester creates “no claim to [Indian] lands, no dominion over their persons” at all—it merely binds Indian tribes to a stronger nation “as a dependent ally, claiming the protection of a powerful friend and neighbor, and receiving the advantages of that protection, without involving a surrender of their national character.”23 Justice John McLean astutely observed:

Every state is more or less dependent on those which surround it; but unless this dependence shall extend so far as to merge the political existence of the protected people into that of their protectors, they may still constitute a state.24

Thus, Worcester held that the Cherokee Nation, which placed itself under the protection of the United States in treaties, retained its self-government and had never been conquered. Rather, the Cherokee Nation continued to exist as a separate and distinct people “being vested with rights which constitute them a state, or separate community—not a foreign community, but a domestic community—not as belonging to the confederacy, but as existing within it, and of necessity, bearing to it a peculiar relation.”25 In short, domestic dependent Indian nations are not conquered nations under federal Indian law or international law; they continue to exist as separate self-governing communities within our domestic political system.

This leaves us with the factual contention that Indian tribes lost their land or sovereignty by conquest. To assess this argument we must first define the term conquest. Strictly speaking, conquer means “to acquire by force of arms” according to Webster’s and conquest refers to “something conquered,” especially “territory appropriated in war.”26 Applying this narrow definition, few American Indian tribes and no Alaska Native tribes were conquered. First, in virtually every instance, Indian land was purchased through treaties or statutes, not appropriated in war.27 The motive and goal of many Indian wars was to remove noncompliant bands and tribes to reservations established by the treaties as their homelands, and tribes fought to remain in ceded areas. But the fact remains that those acres were acquired by purchase, and force was not employed until later and then only to enforce the sale agreements. The Indians’ territory in those instances was not appropriated in war. At most, armed force was a tool used to enforce treaty cessations; that is, in those circumstances it was a questionable police action to be sure, but not conquest as that term is normally understood. Second, it is difficult to find many tribes who lost their sovereignty by force of American arms since, as discussed above, most tribes agreed to come under the protection of the United States and assumed their domestic dependant nation status through treaties. In that sense, the treaties are analogous to the social or political contracts by which other political subdivisions joined the union because they are the instruments by which the signatory tribes came under the protection of the United States and exist within the political system as separate communities with the right of self-government.

Indian wars did occur, but few were outright wars of conquest, fought to appropriate Indian territory or reduce tribal sovereignty, since this was accomplished primarily through treaties of peace, trade, and friendship. To be sure, some Indian nations were defeated militarily, but whether they actually lost any of their land or sovereignty as a result of those particular conflicts requires a careful case-by-case examination yet to be conducted on any comprehensive basis. Until then, we cannot simply assume those tribes were conquered as that term is used in Webster’s dictionary or commonly. Furthermore, the notion of a wholesale military conquest of every Indian nation by force, as is sometimes implied in federal Indian law, is plainly wrong. For example, no shots were exchanged in Alaska. No wars were waged against many tribal nations, such as the Pawnee and others. And many who were in fact defeated militarily did not lose a single acre or suffer reduced sovereignty as a result of the conflict. It would be a misleading fantasy to think conquest occurred in these situations. The law should not arbitrarily sanction the government of those tribes by conquest when it never happened as a mater of fact or law. This wrongly suggests that the United States’ power to govern Indian tribes is derived solely from an extraconstitutional source—military conquest. The United States need not rely on that raw principle to rule Indian tribes, since the Constitution provides a far more legitimate source of federal power to regulate Indian affairs. Though some land was no doubt appropriated in war, no wholesale conquest occurred unless we define conquest far more broadly than Webster’s to include the subjugation and dominion of Indian nations by means other than armed force. Indeed, there were arguably vehicles of conquest other than military force as Manifest Destiny engulfed the Indian nations during the nineteenth century: the use of law, germs that spread disease, culture conflict, destruction of game, habitat, and natural resources, theft and avarice, and so on. But these agents are not comparable to invading, seizing, and ruling another country by raw force of arms, nor are any of these destructive agents, standing alone, capable of conquering a continent inhabited by indigenous nations.

Admittedly, all Indian tribes are subject to rule by armed force, but no more so than any other segment of society—we are all subject to military force if the legitimate need arises. If mistaken and misplaced ideas about conquest are allowed to linger in the law, they can be dredged up at any time by politicians and jurists to exercise unwarranted control over Native people, property, and political institutions, or, worse yet, by other nations who look to federal Indian law to justify warfare against indigenous peoples free from the restraints, protections, and obligations imposed by international law. It is better to be factually clear: relatively little appropriation of Indian territory in war occurred as a matter of fact. For the most part, tribes entered into a protectorate relationship with the United States by treaty agreements, not as a result of military conflict, and the law does not treat the resulting domestic dependent nationhood status as conquest any more than a state that has joined the union through other constitutional means. The misleading and sweeping pronouncements by jurists like the late Justice Reed should be set aside, along with mistaken notions of conquest in the law. We are no longer in a state of war with Indian nations and the judicial mind-set of conquest derived from wartime jurisprudence no longer serves any apparent purpose—judicial saber rattling is highly inappropriate and outmoded in contemporary times. After all, the Indian wars ended in 1890. The last vestiges of those conflicts expired in 1913, when the Chiricahua Apache POWs were released from Fort Sill, Oklahoma, after twenty-seven years of imprisonment.

For the above reasons, the idea of conquest is dubious. The continued use of the law of conquest by federal courts to decide Indian legal questions today is highly questionable—unless the courts still believe they are courts of the conqueror. As seen, the notion of conquest is as complex in federal Indian law as it is in other arenas. Nations may lose wars and not be conquered. And there is a troubling reciprocity. No conquest is permanent, since occupation by the victors is often short and even the most powerful empires fade over time. Today’s conquerors can become the conquered tomorrow. This reconnaissance-level discussion is not intended to provide definitive answers, but to highlight an area of inquiry. Given this minefield, jurists should tread lightly before applying sweeping notions of conquest to decide legal questions.

Turning now to the law of war, the judicial discourse on conquest in federal Indian law leads one to wonder about the role of war in federal Indian policy and whether the rules of war apply to the Indian wars or, for that matter, to settler-state warfare against indigenous peoples in general. American cases strongly hint that loopholes may exist when it comes to war against indigenous peoples. For example, in Montoya v. United States (1901), a case involving Indian hostilities, the Supreme Court observed:

While, as between the United States and other civilized nations, an act of Congress is necessary to a formal declaration of war, no such act is necessary to constitute a state of war with an Indian tribe.28

Despite this language, disparate standards in the law of war should not be applied to the Indian wars. If federal Indian law is construed to sanction a double standard in the law of war, this would establish precedent for other nations to employ violence and military force against indigenous peoples in other lands without the need to observe the rights, protections, and limitations normally imposed upon combatants by the law of nations. That double standard would legitimize wars of genocide against indigenous peoples to be quietly waged by settler states in their backyards. We could not lightly place such a malevolent construction on federal Indian law, which tends to be looked upon and followed by settler states throughout the world as legal precedent for their relations with indigenous peoples. I argue in this chapter that the ordinary rules of war are applicable to the United States’ Indian wars during the nineteenth century and should have been applied, just as they were applied to any other American war.

What was the role of warfare in federal Indian policy? In some instances, the United States commenced defensive wars to repel attack or other immediate threats by Indian bands, nations, or confederacies. Some were waged to put down rebellions. Others were offensive wars of aggression waged to punish Indian nations and bands for a range of alleged just, and sometimes unjust, causes. Some were race wars, pure and simple. From the tribal standpoint, Indian nations waged war for a variety of reasons. They waged defensive wars to repel attack, wars of independence, insurrection, and rebellion, and they waged offensive wars to punish legal wrongs committed against them, such as treaty violations, since resort to American courts to redress legal grievances was generally unavailable during the nineteenth century. The wars were fought in many places by warriors with strong warrior traditions that defined their place in the world, often to achieve personal honor, wealth, and to extract revenge or punishment for wrongs committed against their families and tribes.

At bottom, the Indian wars—regardless of their causes—were part and parcel of a relentless program of Manifest Destiny waged generally to clear Indian nations from the path of white settlement and to force them onto reservations established as their permanent homelands by treaty. US military policy during this period is aptly described in Cohen’s Handbook of Federal Indian Law as follows:

United States military policy was designed to bring natives under control and support the civilian dream of open lands for white settlement. From Indians battling Gen. Armstrong Custer at the Little Big Horn to Geronimo evading the cavalry in Arizona’s hills and deserts, these were battles to the death. Geronimo and his Apaches were imprisoned and exiled to Florida; the Lakota who earlier fought Custer were gunned down at Wounded Knee. By the final years of the nineteenth century, Indian military resistance was no longer a viable option for any

tribal groups.29

The Definition of War and an Overview of America’s Indian Wars

The United States is no stranger to the use of force. It has waged war almost continuously since its inception.30 Judging from that history, we are the most violent people on the planet. The Republic fought Indian nations, separated from the settlers by race, ethnicity, religion, and language, for more than one hundred years (1776–1890), perhaps killing over fifty thousand Indians. During this period of protracted warfare, a military mind-set dominated Indian affairs and found its way into the foundational cases of federal Indian law.31 While on this extended war footing, Indian affairs and policies were administered by the War Department from 1776 to 1876. Indian affairs were conducted as an aspect of military and foreign policy, outside the realm of domestic civilian concern. The use of military force to control Indian tribes was a tool that dominated federal Indian policy as Manifest Destiny swept the continent.32 Even though these measures left indelible marks on Native America, no one has performed a comprehensive legal analysis of the Indian wars and surprisingly little has been written about American Indians and the law of war.

Of course, what constitutes a war is a matter of perspective as well as law. Killing and destruction can be described as a great victory or horrific massacre, depending upon one’s point of view; and there is a thin line between war, murder, and genocide. What is war? We think we know it when we see it, but war is a complex legal condition often surrounded by technical uncertainties. For example, the courts are unsure of the exact amount, level, and stage of hostilities that give rise to a state of war, and it is sometimes hard to know precisely when war actually starts or ends.33

War is defined in American jurisprudence as the contention of external force between two nations authorized by the legitimate authority of the two governments. A lawful public war is either “perfect” or “imperfect.” The Supreme Court explained this dichotomy in Tingy v. Bas (1800). Perfect war is general, unconditional war initiated by a formal declaration of war:

[E]very contention of force between two nations, in external matters, is not only war, but public war. If it be declared in form, it is called solemn, and is of the perfect kind; because one whole nation is at war with another whole nation; and all the members of the nation declaring war, are authorized to commit hostilities against all the members of the other, in every place, and under every circumstance. In such a war all the rights and consequences of war attach to their condition.34

Imperfect war is more limited in scope, as may be authorized and circumscribed by Congress, but very much war in every other respect:

But hostilities may subsist between two nations more confined in its nature and extent; being limited as to places, persons, and things; and this is more properly termed imperfect war; because not solemn, and because those who are authorized to commit hostilities, act under special authority, and can go no farther than to the extent of their commission. Still, however, it is public war, because it is an external contention of force, between some of the members of the two nations, authorized by the legitimate powers. It is a war between the two nations, though all the members are not authorized to commit hostilities such as in a solemn war, where the government restrains the general power.35

Tingy’s definition of war was the law throughout the nineteenth century, when the Indian wars occurred.36 The Indian wars were classified as limited or imperfect war by the Supreme Court.37

The United States’ use of force was an important tool of Manifest Destiny. More than forty so-called Indian wars were fought by the government, according to the Bureau of the Census in 1894.38 The clash between cultures produced warfare on a vast scale. Untold thousands of Indian people died in the Indian wars, according to the census report:

The Indian wars under the government of the United States have been more than 40 in number. They have cost the lives of about 19,000 white men, women, and children, including those killed in individual combat, and the lives of about 30,000 Indians. The actual number killed and wounded Indians must be very much larger than the number given, as they conceal, where possible, their actual loss in battle, and carry their killed and wounded off and secret them.

Applying this data, anthropologist Russell Thornton estimates that 53,500 American Indians were slain in the United States between 1775 and 1890, including 8,500 reported deaths from individual conflicts.39 The body count might easily double if we add the numerous Indian wars that occurred before 1775. Some tribes, hit harder than others, were nearly annihilated by conflict with the Big Knives.

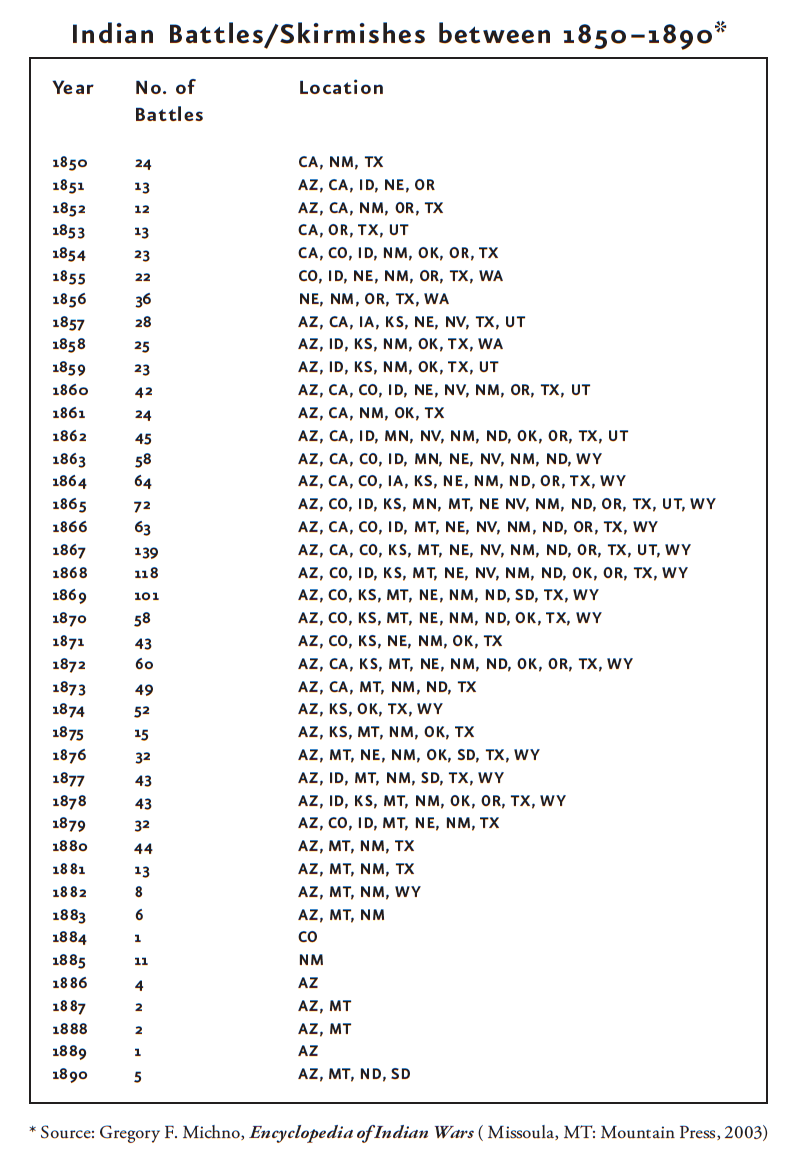

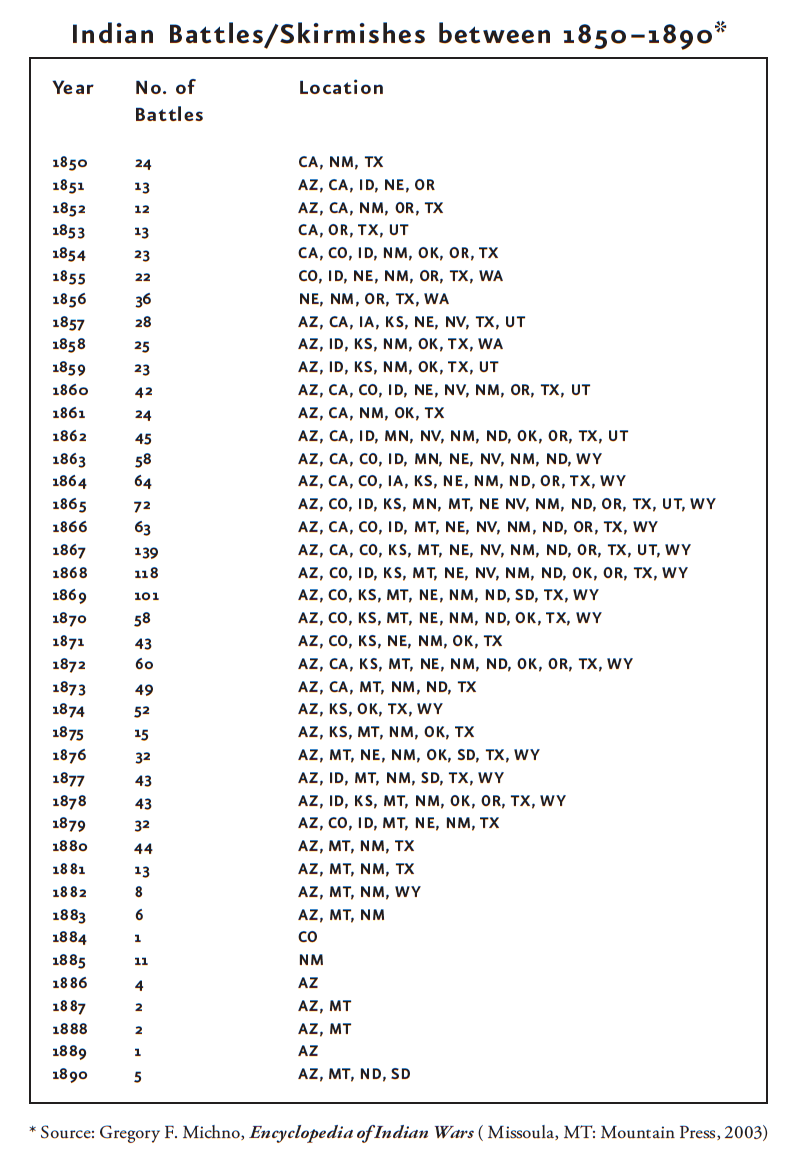

Between 1850 and 1890, fighting Indians was almost a daily occurrence for Americans, according to historian Gregory Michno.40 His startling survey of major armed conflicts discloses an unrelenting forty-year military campaign conducted against Native Americans throughout a vast theater of war. His data for the American West alone (not including extensive warfare east of the Mississippi River before 1850) reveals a nation fully at war with its indigenous peoples:

Military might was not the only source of violence against Native Americans during this period. Civilians were also prone to violence. They took up arms against Indians so frequently that Michno could not tally their acts of aggression. He simply stated that thousands of reported deaths went uncounted since they were not part of an organized military action.41 Acts of hostility by gun-toting settlers, legal or otherwise, contributed greatly to the carnage:

Whites killed Indians in every state and territory, but perhaps most dramatically along the Pacific coast. In Washington, Oregon, and California, Indian populations declined as if a biblical flood had swept them from the land. The army may have accounted for several hundred fatalities, but thousands more perished from disease, malnutrition, and murder. Next to disease, white civilians with guns were the most dangerous threat to Indian survival.42

No other ethnic group in the United States has faced the muzzles of American guns like the American Indians. Modern Native Americans are the descendants of survivors who were spared.

What drove Indians and whites to war? No one has comprehensively examined with particularity the causes and objectives of the many Indian wars found in US history. Any such analysis would likely reveal finger-pointing among the combatants, with each side blaming the other for war. We can only supply legal guidelines for judging those contentions, beginning with the Connors case study.

The Cheyenne Indians Are kaki suriru’—A Very Brave People

It is fitting that we examine the legal basis of the Indian wars through a Cheyenne case study. They are a people with strong warrior traditions who migrated to the plains in the 1600s from as far away as the Hudson Bay region of present-day Canada. The Tsis tsis’ tas originally lived in earth lodge dwellings like their aboriginal Plains Indian neighbors, but later took up a nomadic way of life with the acquisition of horses. This far-flung tribe ranged throughout the western plains in pursuit of the buffalo herds from Montana through Wyoming, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado, and Oklahoma. They bore more than their share of war with the Big Knives. “As a child growing up among two Cheyenne women,” remarked Richard Williams in 2007, “I was often told that the Cheyenne were the bravest of all warriors and were willing to fight when others feigned bravery, causing them to withdraw from the battlefield.” Many Pawnee war stories of my own tribe confirm from firsthand experience the valor and fighting spirit of the strong-hearted Cheyenne warriors, brave men and women who pledged to defend their people and way of life. The following story, which is important among my own family, recounts events that set the stage for those described in the Connors case.

At dawn, in the winter of 1876, my great-grandfather, Tawi Hisi (meaning, “Leader-of-the-Group”), and ninety-nine other Pawnee scouts trotted along the red earth trail toward Morning Star’s village. Morning Star was the Cheyenne chief known in history books as Dull Knife. His village lay well hidden in the Bighorn Mountains of Wyoming. The Pawnee scouts were positioned in the center of the command with orders to take the village. On their left flank, one hundred Shoshoni scouts climbed the ridge while the white soldiers rode on the right flank, across the stream, as the command proceeded up the little valley.

The Cheyenne had been prominent, along with their Sioux allies, in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, when Custer was killed in one of the greatest military victories ever achieved by the Plains Indians. During that summer, the army came under enormous pressure to find and punish the Indian victors, yet they could not be located. Thus, the famed Pawnee scouts were recruited to assist in locating their hereditary foes, the Sahi (Cheyenne) and Pariksukat (Sioux). And now, five months after Custer’s defeat, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe had been found at last!

Blowing their eagle-bone war whistles, the Pawnee stripped down and went into the fight on painted ponies recently captured from the Lakota Sioux. The ensuing battle raged all day as the Cheyenne put up a fierce resistance against their multiple attackers. Many were lost on both sides, but in the end the Pawnee scouts occupied the village and captured the Sahi pony herd.43 Afterward, the snow began to fall and many Pawnee soldiers received new names to mark their hard-won victory, as was their tribal custom. That was when Leader-of-the-Group became Echo Hawk (Kutawikucu’ Tawaaku’a), the name that my family bears to this day. Morning Star’s people escaped but surrendered that spring. Many were removed to Fort Reno, in the Indian Territory of Oklahoma, to live with their Southern Cheyenne relatives, bringing the Sioux War of 1876 to a close.

From this and many other encounters, we know Cheyenne Indians are kaki suriru’, “without fear.” The Cheyenne are respected among the Plains Indians as a remarkable, courageous people. I can recall a particular dawn morning in my youth when I sat in a canyon watching the Morning Star rise with my friend Raymond Spang, a Northern Cheyenne. Trading stories, I told him about our Pawnee beliefs concerning the mighty Morning Star, who rises in the dawn sky to chase the other stars before him. He replied, “We also have a Morning Star: the man better known as Dull Knife in history books.” This chapter concerns Morning Star, the man.

The Connors Case and the Flight of Morning Star

On October 1, 1878, Morning Star and Little Wolf were leading their people across western Nebraska when they came upon Milton Connors’s ranch. The fleeing Indians, who had escaped from the Cheyenne and Arapahoe Indian Reservation near Fort Reno, Indian Territory, located on the Canadian River in the present-day state of Oklahoma, where they had been sent after their surrender at the end of the Sioux War, were being pursued by soldiers. So far, they had outfought and outgeneraled the generals who pursued them on their exodus. Since September, they had traveled northward across the Cimarron, Arkansas, Sappa, Republican, Arikaree, and Platte rivers on a remarkable fifteen-hundred-mile journey to freedom in their Montana homeland. Often traveling at night, they were guided by an elderly woman blessed with a mysterious power to see in the dark. On this day, the hungry refugees made off with forty horses, forty steers, and one mule from

the ranch.

Many years later, the Nebraska rancher sued the United States and Cheyenne Indians to recover damages for his lost livestock. The claim in Connors v. the United States and the Cheyenne Indians (1898) was brought under the Indian Depredation Act of 1891.44 This law allowed the Court of Claims to hear citizen claims for property taken or destroyed by Indians. Specifically, it granted the court authority to determine all claims arising after 1865 “for property of citizens of the United States taken or destroyed by Indians belonging to any band, tribe, or nation, in amity with the United States, without just cause or provocation on the part of the owner.” Under the act, a citizen could recover damages only if the tribe to which the Indians belonged was at peace (or “in amity”) with the United States at the time the property was taken. Thus, the threshold inquiry was whether the Indians’ tribe was at peace or war with the United States when the injury occurred. If the tribe was at peace, the citizen was entitled to recover money damages and the award could be deducted from tribal annuities. However, if the tribe was determined to be at war with the United States, the obligations of peace did not pertain and the claim would therefore be disallowed.

Connors was heard by Charles J. Nott, a judge nominated to the bench by President Abraham Lincoln in 1865. The New Yorker was a former cavalry officer in the Union army. During the Civil War, he spent thirteen months as a prisoner of war in a Confederate prison. By the time he retired from the bench at the beginning of the twentieth century, Nott was the chief justice of the US Court of Claims and the longest-serving federal judge in the country. This judge had seen war and was eminently qualified to hear cases on that subject. The United States and Cheyenne defendants were represented by an assistant attorney general. The findings of fact recited in Judge Nott’s opinion are summarized as follows.

The court began its opinion by observing that the Northern Cheyenne Indians “had borne a distinguished part in the Sioux War of 1876, but had surrendered and made peace with the United States.”45 At the time of their surrender, in May of 1877, they numbered about 1,800 persons. About half were allowed to stay in their tribal homeland and ultimately settled on the Tongue River Reservation in Montana.46 However, 937 persons led by Morning Star, Little Wolf, Wild Hog, and Old Crow were removed to the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Reservation at Fort Reno, Indian Territory. They went reluctantly, but with the understanding that if their new home proved unsatisfactory they could return to their native country.47 After a year of sickness, starvation, and death, and repeated requests to return, “320 of them in September, 1878, broke away from the reservation.”48

Under the leadership of Morning Star and Little Wolf, the tiny, starving group of Indians slipped away under the cover of darkness, leaving their tipis standing before the watchful soldiers. The Cheyenne were overtaken 120 miles from Fort Reno and a parley ensued. The commanding officer demanded that they return, but “Little Wolf, whom Captain John G. Bourke characterizes as ‘one of the bravest in fights where all were brave,’ said ‘We do not want to fight you, but we will not go back.’”49 Up to that time, the Cheyenne “had committed no atrocity and were in amity with the United States and desired to remain so.”50 Unfortunately, the “troops instantly fired upon the Cheyenne and a new Indian war began.”51 The court commented on that fateful incident:

That volley was one of many mistakes, military and civil, which have been the fatality of our Indian administration, for the officer who ordered it thereby instituted an Indian war, and at the same instant turned hostile savages loose upon the unprotected homes of the frontier and their unwarned, unsuspecting inmates. The Cheyennes outgeneraled the troops. They fought and fled, and scattered and reunited. They fought other military commands and citizens who had organized to oppose them, and in like manner they again and again eluded their opponents, making their way northward over innumerable hindrances. They had not sought war, but from the moment they were fired upon they were upon the warpath—men were killed, women were ravished, houses were burned, crops destroyed. The country through which they fled and fought was desolated, and they left behind them the usual well-known trail of fire and blood.52

The Human Beings split into two groups soon after they crossed the Platte River in Nebraska. By then, hundreds of American troops had been called into action to hunt them down.53 The group led by Little Wolf escaped and successfully made the fifteen-hundred-mile journey to freedom in Montana. However, the troops captured forty-nine men, fifty-one women, and forty-eight children of Morning Star’s band on October 3, two days after the raid on the Connors ranch, and placed them into custody at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. Though incarcerated, the prisoners of war still refused to return to the detested Indian Territory. By January, Captain Henry Wessells, the frustrated commander, turned to means used by “animal tamers” to subdue “wild beasts” and soon resorted to massacre.54 Quoting from army reports, Judge Nott wrote:

In the midst of the dreadful winter, with the thermometer 40 degrees below zero, the Indians, including the women and children, were kept for five days and nights without food or fuel, and for three days without water.55 At the end of that time they broke out of the barracks in which they were confined and rushed forth into the night. The troops pursued, firing upon them as upon enemies in war; those who escaped the sword perished in the storm.56 Twelve days later the pursuing cavalry came upon the remnant of the band in a ravine 50 miles from Fort Robinson. “The troops encircled the Indians, leaving no possible avenue of escape.” The Indians fired on them, killing a lieutenant and two privates. The troops advanced; “the Indians, then without ammunition, rushed in desperation toward the troops with their hunting knives in hand; but before they had advanced many paces a volley was discharged by the troops and all was over.” “The bodies of 24 Indians were found in the ravine—17 bucks, 5 squaws, and 2 papooses.” Nine prisoners were taken—1 wounded man, and 8 women, 5 of whom were wounded. The officer in command unconsciously wrote the epitaph of the slain in his dispatch announcing the result: “The Cheyennes fought with extraordinary courage and firmness, and refused all terms but death.” The final result of the last Cheyenne war was, that of 320 who broke away in September, 7 wounded Cheyennes were sent back to the reservation.57

Like red and black ants, the Indians and whites fought until every last Cut Finger lay dead or wounded in the crimson snow. The Indians died fighting for their freedom, while the soldiers died fighting for Manifest Destiny. Captain Wessells, who instigated the tragedy by his mistreatment of the prisoners of war, was shot in the head, and Sargent William B. Lewis was awarded the coveted Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest tribute the nation can pay to a soldier in wartime, for his actions that day.58 The survivors included wounded men such as Old Crow, Wild Hog, Left Hand, Tangle Hair, Porcupine, and Noisy Walker. Seven of these Tsis tsis’ tas soldiers were taken to Kansas, where they were tried for murder in 1879 in civilian courts, but acquitted for lack of evidence.59 In contrast, none of the white soldiers or citizens who killed Cheyenne noncombatants were tried for murder, presumably because folks naturally assumed their acts were lawful acts of war.

Though Judge Nott was himself a seasoned war veteran, one can almost hear him gasp as he wrote the opinion. He was troubled by several factors that illustrated “the extraordinary difficulty which the court has had to encounter in dealing with these Indian depredation cases.”60 If this were an ordinary case, he wrote, “there would really be no defendant before the court, for these bands had utterly ceased to exist before the suit was brought.”61 Virtually everyone in Morning Star’s band had been killed. Moreover, Nott was confounded by the uncertain Cheyenne legal status.

These Indians, indeed, in 1878 occupied an anomalous position, unknown to the common or civil law or to any system of municipal law. They were neither citizens nor aliens; they were neither free persons nor slaves; they were wards of the nation, and yet, on a reservation under a military guard, were little else than prisoners of war. Dull Knife and his daughters could be invited guests at the table of officers and gentlemen, behaving with dignity and propriety, and yet could be confined for life on a reservation which was to them little better than a dungeon, on the mere order of an executive officer.62

Above all, Judge Nott was troubled by the acts of the military. He wondered whether their actions were legal and whether the Human Beings had a lawful right to leave Indian Territory and travel peaceably to their native land. In fact, those questions were strenuously argued by the parties.

It has been argued in this case with great earnestness that these Cheyennes had a lawful right to leave the reservation and travel peaceably back to their old homes; and that they did not begin the conflict, and merely resisted force by force; that their acts were lawful and the action of the pursuing troops unlawful.63

Nott did not rule on these questions since it was “impossible to define their status from a legal point of view” and his central inquiry under the Indian Depredation Act was simply to determine whether the Cheyenne bands were “in amity” with the United States in order to decide the citizen’s property claim. Thus, Nott sidestepped the issue, stating, “Whether they could have sued out a writ of habeas corpus and been set free by judicial authority is not for this court now to decide.”64

As implausible as it may have seemed to Judge Nott in 1898, the Human Beings did have legal rights that courts could recognize. For example, United States ex rel. Standing Bear v. Crook (1879) involved a similar situation concerning the Ponca Indians of Nebraska.65 They, too, had been removed to Indian Territory, where 158 died within a year or so. A small band led by Chief Standing Bear fled the reservation without permission of the government and returned to their Nebraska homeland. They were arrested shortly after their arrival by General George Crook at the request of the secretary of the interior and incarcerated pending their return to Indian Territory. Standing Bear sued for his freedom in a habeas corpus action that challenged the legality of their confinement. Judge Elmer Dundy allowed the suit, holding that Indians are “persons” within the meaning of the federal habeas corpus act with standing to bring such cases.66 He then examined the legal basis for the Indians’ incarceration and could find no authority whatsoever.67 Since no war existed and no crime had been committed, the government had no power to confine the Ponca Indians. The Standing Bear court aptly observed that if Indians could be forcibly removed to a reservation in Indian Territory by the government without any apparent legal authority, why not place them in prison?

I can see no good reason why they might not be taken and kept by force in the penitentiary in Lincoln, or Leavenworth, or Jefferson City, or any other place which the commander of the forces might, in his judgment, see proper to designate. I cannot think that any such arbitrary authority exists in this country.68

In the absence of any authority for confining or removing the Ponca Indians back to Indian Territory, the court ordered their release from custody.

Under Standing Bear’s rationale, Morning Star’s people had a lawful right to leave Indian Territory and peaceably return to their native land, since they were at peace and had committed no crime in 1878. By the same token, the soldiers had no apparent legal authority to demand their return or fire upon them. Since the soldiers’ acts in provoking the conflict were most likely unlawful under Standing Bear, it is no wonder that Judge Nott was uncomfortable.

Nott denied Connors’s claim since the Indians had been driven to war by the time of their raid on his ranch. In such instances, the court held, neither the United States nor the Indians are liable for damages under the act. This is a correct result, which was affirmed by the Supreme Court on appeal. However, the Connors case leaves us to wonder about the elephant in the room.

Could the tragic events of 1878–79 have been prevented by the courts? As demonstrated in the Standing Bear decision of 1879, contemporary courts could have protected Morning Star’s right to travel peaceably to Montana since the Tsis tsis’ tas left the reservation during a time of peace and had committed no crime, according to Connors. Unfortunately, access to the courts was generally unavailable to American Indians during this period. Their predicament was captured in the book Cheyenne Autumn (1953), in which author Marie Sandoz recounts the thoughts of Little Wolf as he surveyed his worn-out people moving across the plains that winter.

The Indian is left without protection of law in person, property or life. He has no personal rights. He may see his crops destroyed, his wife and children killed. His only redress is personal revenge.69

They had no recourse to American courts. Connors also raises a larger question: to what extent was America’s use of force against Indians lawful? Were the military’s actions at Fort Robinson legal? Was the Sioux War of 1876 a legal conflict? What about other conflicts, like the Sand Creek Massacre and the forty Indian wars referenced by the Bureau of the Census? Definitive answers must await future research by scholars into the facts and circumstances leading to each conflict and the documents, if any, that authorized them. Then, we can apply the law of the conquerors as a measuring stick. To encourage that research, some legal principles and tentative conclusions are discussed below.

The Law of War in the Americas

Only men and ants engage in war. Ants have an excuse: they are driven into all-out warfare by biological imperatives that are regulated by the law of nature. Similarly, a nation’s use of military force is governed by immutable principles of natural law. That body of law is called the “law of war.” It is “founded on the common consent as well as the common sense of the world” and firmly embedded in international law.70 For centuries, this component of international law has allowed nations to use force legally, both defensively against attack and offensively to punish wrongdoers or exact compensation for legal wrongs.71

It is ironic that naked force can be clothed in the law. Warfare is the supreme expression of violence and destruction among our species. Large-scale violence must be governed by law, with rules of war adhered to by every nation. Otherwise, the antlike carnage would constitute horrific criminal conduct, if not crimes against humanity. Warmongers could be prosecuted as common criminals, along with foot soldiers who do their bidding. To protect those folks, the law of war distinguishes between violence committed as part of a public war and violent acts committed without the sanction of war. In the first instance, the killing is justified if done within the proper bounds of warfare; in the latter, individuals who commit acts of violence are considered terrorists and murderers who are subject to punishment under domestic law. For example, if I shoot a roomful of people during wartime as a lawful belligerent, the killing is lawful and I might receive a medal. The same act is murder if committed in times of peace. We need rules of war to legalize violence.

In international law, war can only be conducted by nations. It is usually waged between two or more independent nations, but a state of war can also exist when one of the warring parties is not an independent nation in the ordinary sense, as in the case of civil wars or rebellions72 and wars between settler states and indigenous tribes within their borders.73 Though Indian tribes are not considered independent nations by international or federal law, they still retained the power to wage war as domestic dependent nations, according to the Supreme Court.74 Thus, the law of war is fully applicable to the United States’ Indian wars. During the nineteenth century, American law defined war as the use of force between two nations authorized by the legitimate authority of the two nations, and the law distinguished between general and limited war.75 The Indian wars were considered limited or imperfect wars.

In all the above circumstances, the use of military force by nations is governed by the law and usages of war as set forth in international law. The well-established customary rules of war are peremptory norms—that is, higher laws based upon long-standing state practice that cannot be altered by treaties or domestic law.76 They govern every nation’s decision to go to war (jus ad bellum) and the manner in which it is conducted (jus in bellum). The rules governing American warfare, in particular, are derived from international and domestic sources. Thus, to understand rules applicable to the Indian wars, we must first examine principles of international law pertaining to war, and then look at US law.

International Law

The law of nations is the starting place for our analysis. No country can disregard international norms regarding the use of force without being branded an outlaw. Thus, to determine questions of war, the Supreme Court wisely consults the law of nations as well as the Constitution.77 As discussed earlier, international law originated in Europe as a product of medieval Christian thought. It was conceived to define relations among the nations of Europe, guide their dealings with the non-Christian world, and provide rules for colonizing the New World.

Rules of war were espoused early on by founding jurists, such as Franciscus de Victoria, Alberico Gentili, and Emmerich de Vattel, to provide guidelines for invading the Americas.78 Many of their legal principles—such as the doctrines of discovery, conquest, and just war—were readily incorporated into the fabric of American law in cases like Johnson v. M’Intosh, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, and other jurisprudence. In particular, the law of war was adopted in whole cloth. In the Prize Cases (1862), for example, the Supreme Court consulted international law to determine whether a legal state of war existed during the Civil War. The Court applied it to evaluate President Lincoln’s decision to go to war (jus ad bellum) and the belligerents’ use of force (jus in bellum) during that conflict.79

The decision to go to war (jus ad bellum) entails consideration of several fundamental concepts. First and foremost is the distinction between a war of defense and an aggressive war. A nation can lawfully use force in only two circumstances: (1) defensively, to repel attack or invasion and (2) offensively, to punish legal wrongs.80 Defensive war may be waged immediately without a declaration of war. It is done solely in self-defense when necessary to repel attack or other immediate threats. In those circumstances, the use of force is the unquestioned right of every sovereign nation. By contrast, stringent requirements must be observed before an offensive war can be waged.

Offensive wars are those of aggression and invasion. They may be waged only when just cause exists, that is, when one nation commits a legal wrong that injures another. Legal wrongs can be numerous and sometimes suspect, depending on how they are defined and by whom,81 but they do not include religious or ideological differences, racial or ethnic animosity, or the bare pursuit of empire, domain, or conquest. In the absence of bona fide legal wrongs, none of those illegitimate motives provide just cause for war. After all, the just-war doctrine springs from Christian concepts of morality and justice—essential notions that mark right from wrong—which are intended to place in check the immoral dark side of human nature. Under Christian doctrine, certain evils can never justify making war, such as the lust for power, cruelty, or a desire to do wrong.82 Victoria labeled three causes of war as inherently unjust: (1) differences of religion, (2) extension of empire, and (3) personal glory of the prince.83 That is why customary international law does not consider jihad, holy wars, ethnic-cleansing campaigns, Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, and Hitler’s Blitzkrieg to be just wars. In all instances, the law of nations requires an acceptable legal basis for commencing offensive war. In this sense, a lawful just war resembles a “judicial procedure” between nations to redress wrongs and vindicate justice, except generals, not judges, decide the outcome.84 In short, the just-cause doctrine requires aggressor nations to justify their use of violence, as seen in the George W. Bush administration’s attempt to identify legal wrongs committed against the United States by Iraq that justify our invasion of that country. Many are not persuaded that just cause exists, since no weapons of mass destruction were ever found, and the bare idea of bringing democracy to an utterly foreign land with a vastly different cultural and political heritage is not a just cause for war because it is tantamount to the extension of ideological empire.

Due to the grave consequences that attend war, international law imposes procedural safeguards on the use of offensive warfare.85 First, the proper body in each nation invested with the power to wage war must make findings of (1) just cause to identify the wrong committed and (2) a prudential judgment that war is actually in the national interest.86 These findings are akin to findings of a court of law that must be made before a judgment is entered to exact punishment or compensation under domestic municipal law.87 Next, the nation must issue a formal declaration of war before commencing an offensive war.88 The declaration serves important purposes. It gives notice to the offender of the legal wrong and a demand for satisfaction to allow it opportunity to settle the dispute peaceably. It notifies citizens and other nations of the change in legal relations occasioned by the existence of war and, finally, it sets the parameters for the armed conflict. Japan disregarded these obligations in the infamous surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, executed before a declaration of war on the United States. That is why its attack was deplored by the world.89 In short, a declaration of war is the legal equivalent of a judicial judgment that legally ushers in an offensive war to redress wrongs done to a nation. After World War II, the United States seems to have dispensed with this formality. It invaded Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and other places without issuing a declaration of war, leaving scholars to debate the legality of those murky wars of aggression, which are beyond the scope of this book. It seems we can declare war on most other things, like poverty, crime, drugs, and terrorism, but not the actual countries we invade.

Finally, offensive war must be conducted according to several elements of just war. Under the principle of right authority, the initiation of offensive war can only be done by the entity vested by domestic law with the power to make war.90 The use of force must be in proportion to the wrong done since it is compensatory punishment for an injury inflicted upon a nation, and nothing more.91 It must be waged only as a last resort after peaceful means for resolving the dispute have failed.92 Finally, even if all of the above elements are present, a war is unjust if waged out of hatred, prejudice, or other improper motives.93

International law also regulates the conduct of war by the foot soldiers (jus in bellum). It prescribes a wide variety of rules pertaining to the rights, treatment, and punishment of captured soldiers as belligerents; rules for capturing and confiscating enemy property; prohibitions against killing innocents and noncombatants; the treatment of debts, contracts, and treaties among enemies and belligerents during wartime; and all other facets of war. These rules provide acceptable boundaries for combat, mitigate the horror and cruelty of war, and prevent escalating retaliation among combatants. War quickly turns into atrocity and genocide when they are not observed. Consequently, violations constitute war crimes punishable in appropriate international, military, or other tribunals.

US Domestic Law

The Indian wars were public wars under US law, just like any other American war during the nineteenth century.94 The courts of the era recognized that war can exist when one belligerent is an Indian nation.95 They acknowledged that the United States can wage war on domestic dependent Indian nations who, by the same token, retained legal power to wage war on the United States.96 Felix S. Cohen, the father of federal Indian law, observed in 1942 that the power to make war, which is a fundamental attribute of sovereignty in international law, was recognized in Indian nations well into recent times. He stated:

This power has been recognized in Indian tribes down to recent times, and there are still on the statute books laws which contemplate the possibility of hostilities by an Indian tribe. The capacity of an Indian tribe to make war involves certain definite consequences for domestic law. Acts which would constitute murder or manslaughter in the absence of a state of war, whether committed by Indians, or by the military forces of the United States, may be justified as acts of war where a state of war exists. Hostile Indians surrendering to armed forces are subject to the disabilities and entitled to the rights of prisoners of war.97

The Indian wars were considered wars of the imperfect or limited kind, but war nevertheless in the legal sense.98 Judge Nott used this test to define the Indian wars in a case involving the Apaches:

The books hold that when war exists every citizen of one belligerent is the enemy of every citizen of the other. Conversely, this court holds that when every white man, at a given time and in a certain territory, is found to be the enemy of every Indian, and every Indian is found to be the enemy of every white man, a condition of amity does not exist within the meaning of the fifty statutes which employ the word “amity” to prevent war upon the frontier. If a party of bad white men or a party of bad Indians engaged in rapine and murder and the remainder of the white community and of the Indian tribe did not take up arms, it was crime, but not war. If, on the contrary, the condition of affairs was such that every man on the one side stood ready to kill any man on the other side and military operations took the place of peaceful intercourse, hostility so far existed that amity ceased to exist…99

The normal rules of war apply to the Indian wars, just as they did to every other public war in the same period. During the nineteenth century, American courts routinely applied them to every type and facet of public war. It did not matter whether the war was against foreign nations100 or rebels at home,101 or whether the war was a general one commenced by a declaration of war or limited warfare authorized by Congress. Since the Indian wars were recognized as public war, there is no reason why the rules should not apply. There is no basis to assume that some sort of exception in the law existed for Indian wars. Researchers should, therefore, apply normal American rules of war to the Indian wars. Some of those rules, which were well settled in the nineteenth century, are discussed next.

America’s decision to go to war in the nineteenth century was governed by international law (jus ad bellum) and the War Power Clauses of the US Constitution, which allocate war powers between Congress and the president. Under the Constitution, only Congress may declare war, whereas the president is empowered to conduct war.102

The just-war doctrine was adopted by statute. The Northwest Ordinance was enacted by the Continental Congress in 1787 to govern the Northwest Territory and reenacted by Congress two years later.103 Article 3 provides:

The utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their land and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and in their property, rights and liberty, they never shall be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress. (emphasis added)

This law makes the just-war doctrine of the law of nations applicable to Indian wars waged within the Northwest Territory, and those wars must be “authorized by Congress.” For the sake of uniformity, these same requirements arguably pertain to other territories subsequently obtained by the United States, such as the Louisiana Purchase, especially in the absence of a clear expression of congressional intent to the contrary. Otherwise, the American landscape would be subjected to a strange, checkerboard law of war.

A review of the Indian wars will reveal that many, but not all, were authorized, or at least mentioned, by statutes passed by Congress, primarily appropriation laws enacted after hostilities commenced. However, the inquiry does not end there, since the Northwest Ordinance also requires those wars be just. Thus, one must determine whether the conflict passes muster under the just-war doctrine. Furthermore, in the case of an offensive war of aggression against an Indian tribe, international law requires us to evaluate the sufficiency of sometimes cryptic language employed in those statutes to see whether it provides sufficient notice to fulfill the important purposes of declarations of war. For example, the “Act to increase the cavalry force of the United States, to aid in suppressing the Indians” (August 15,

1876) merely appropriates money and authorizes the president to employ more troops “in existing Indian hostilities.” Such language does not provide minimal information normally required in declarations of war.

American law also recognized the distinction between offensive and defensive war. The president could wage defensive war to repel attack without a formal declaration of war.104 However, he could not initiate offensive war. Invasion and general wars of aggression could only be initiated by a formal declaration of war issued by Congress.105 And, in the case of Indian wars, the Northwest Ordinance required them to be “just and lawful wars authorized by Congress.”

The conduct of American warfare during the nineteenth century was governed by jus in bellum, regardless of whether the war was of the general or limited kind.106 As illustrated in Tingy, international law applied with full force to limited wars, even though their limits and operation were circumscribed by parameters set by Congress. Thus, when a limited war is involved, such as an Indian war, one must consult pertinent acts of Congress to learn who is authorized to commit hostilities, where those hostilities may be committed, against whom, and other limitations imposed by Congress.107 Combatants in domestic warfare were clearly required to observe the customary rules of war. It is therefore fair to conclude that those same rules were equally applicable to Indian wars.108 Those rules were adopted in the US Army’s Lieber Code of 1863 to guide the military in the proper conduct of warfare under international law.109

The Lieber Code prohibited American soldiers from killing unarmed civilian noncombatants.110 It granted captured soldiers all of the accepted legal rights and protective status as prisoners of war, and it bestowed upon them the rights of belligerents—exempting warlike acts committed by captured soldiers in wartime as criminal offenses.111 The code prohibited mistreatment of prisoners of war, such as the infliction of suffering by cruelty, want of food, or other barbarity.112 It required them to be fed and treated with humanity.113 While escaping prisoners could be shot and killed, their attempted escape was not considered a crime.114 Finally, the killing or inflicting of additional wounds upon an enemy already wounded was an offense punishable by death.115 As you’ll see, the code was not followed by the US Army during its pursuit and capture of Morning Star’s people.

The Use of Military Force against Morning Star’s People Was Illegal

Based upon Judge Nott’s findings of fact made in the Connors case, it is evident that the United States’ use of force against the Northern Cheyenne was illegal in several important respects.

First, it was an unconstitutional offensive war initiated and conducted without the required authorization by Congress. The bluecoat troops were not repelling an attack or invasion when they instigated the conflict. Their assault was not waged in self-defense. The Northern Cheyenne were at peace and had committed no crimes or atrocities when the firing began. They were lawfully traveling to Montana, as established in Standing Bear, and nothing more. The bluecoats lacked any apparent legal authority to order them back to the reservation or fire on them. As such, this was not defensive warfare. Only Congress can initiate offensive war. Since it did not do so, the use of force, though perhaps authorized by General Philip Sheridan, was not authorized by the legitimate authority prescribed by the Constitution. The government’s use of force was therefore illegal because it violated both domestic law and international law’s principle of right authority—the very rules made by the conqueror.

By contrast, under the same rules, the Tsis tsis’ tas were lawful belligerents waging a defensive war. They repelled armed attack in self-defense, as allowed by the law of nations. Domestic law fully recognized their power to wage war as a domestic dependent Indian nation. Indeed, their capacity to maintain relations of war and peace was recognized by treaty.116 From their standpoint, the incidents in Connors met the criteria for a defensive Indian war. As stated by Judge Nott, “every white man, at a given time and in a certain territory, is found to be the enemy of every Indian, and every Indian is found to be the enemy of every white man.”117

Second, the United States lacked just cause to wage an offensive war against the Human Beings. The just-cause requirement was imposed upon the government by the Northwest Ordinance and international law: a nation can wage offensive war only to punish legal wrongs. As Judge Nott found, the Northern Cheyenne were at peace and had committed no crime. They were engaged in lawful conduct, as illustrated in the analogous Standing Bear case. The Connors opinion does not disclose the reason why the soldiers fired on the Indians. However, historians determined that General Sheridan, the commanding general of the Division of the Missouri, feared that the government’s failure to stop Morning Star would be viewed as a sign of weakness by other Indian tribes, which could jeopardize the government’s reservation system.118 After all, if Indians can simply leave their reservations, the government’s apartheid system would be undermined. This policy concern motivated Sheridan throughout the affair. In November of 1877, he communicated his concerns to Washington:

[U]nless these Indians are sent back, the reservation system will receive a shock which will endanger its stability. If Indians can leave without punishment, they will not stay on reservations.119

Despite this policy concern, leaving an Indian reservation was lawful—a far cry from committing a legal wrong against the United States.120 In the absence of just cause, the war was illegal under both the law of nations and the statutory command of the Northwest Ordinance that no war be waged against Indian tribes without just cause.

Third, the domestic rules for conducting war were violated by the troops. Once Morning Star’s people were captured, they were entitled to the treatment and privileges of prisoners of war provided in the Lieber Code, which required the military to conduct warfare within the bounds of acceptable international norms. The deprivation of food, water, and fuel in the Fort Robinson stockade by Captain Wessells violated Section 3, which expressly forbade the infliction of suffering “by cruel imprisonment, want of food…or any other barbarity.”121 The Cheyenne POWs were required to be fed and treated with humanity, not starved, deprived of water, nor subjected to freezing temperatures. Above all, the Lieber Code required that unarmed persons “be spared in person, property, and honor as much as the exigencies of war will admit.”122 Was it necessary to kill the unarmed women and children who escaped from the stockade into the winter storm? Further, the code strictly forbade the infliction of additional wounds upon an enemy already wounded—an offense made punishable by death—but that rule was ignored during the breakout from the stockade.