Day 1, Wednesday

DAY OF MERCURY/HERMES

A FEW DAYS LATER, ANTHIA WALKED SLOWLY with her husband, Philetus, and son, Nikias, in the agora. They were on their way home and had just left their small vendor space, the place where Anthia and some of the other wives sold the fish their husbands caught. It had been a slow morning, and she was sure that the poor business was compounded by the recent spate of accusations in Ephesus against fishmongers. Some had been accused of selling inferior and even rotten fish at high prices, and that perception had spread to the larger populace; Anthia and the other women were working hard to dispel the notion by providing high-quality fish.

The men had caught so few fish in their nets, just some small anchovies and sardines. They had tried for the bigger fish in the harbor, including tuna, but had not been successful. Their fishing was not going well in general lately, and Anthia knew that Philetus and his koinonoi, partners, were worried.

Anthia had her own ideas about where the fish had gone, but she did not dare say anything. Of course, the bigger question remained, Where might we find food? Anthia’s stomach rumbled, and when she touched her belly, the baby kicked. Yes, you are hungry as well, she thought.

It was late morning, time for rest and food, the latter for those who could afford it. Her family usually ate two meals per day, if they were lucky. Last year, her husband had hoped to improve their situation and status by joining with other local fishermen in an association. The association had given them the ability to bid for fishing contracts from wealthy families as well as contracts with salting houses. The association also helped its members manage the relentless taxation of the Romans. The Romans controlled the harbor, and those who fished in it owed steep taxes on everything they caught. In a public declaration of the importance of the fishing profession in Ephesus and their ability to pay their taxes, their association had contributed toward the building and dedication of the new fishery toll office. They also had, quite appropriately, set up a monument listing the names and status of the contributors.

Anthia smiled when she pictured her husband’s name near the bottom, after the Roman citizens. Philetus. Free man. 6 denaria. She knew that the association was unusual in its membership, as most guilds were composed of people from the same class and status level. Theirs was intentionally mixed, and she was grateful to the Roman citizens who had been willing to form an association that welcomed fishermen and fishmongers from further down the status ladder.

It had been a time of such pride and honor. But now things were different. How will we survive? she wondered. The catch is so small most days, and after selling the fish and paying the taxes, there is not much left. They usually kept a couple of small fish for their family, to guarantee that they would have something to eat that day. But the income from selling the rest paid their rent and gave them the ability to buy cloth, fuel for cooking, and other food. Mostly they lived on grains, olive oil, vinegar, diluted wine, and lentils or beans. A real treat was a fresh vegetable or piece of fruit.

The noises of vendors hawking their goods mixed with the laughter of children and the sounds of sheep, pigs, and wild dogs. Anthia let her mind wander as she walked, and as they passed Dorema’s favorite vegetable stall she was hit once again with the realization that Dorema was dead. A wave of grief covered her, drowning out the noise of the busy marketplace.

Associations

In the ancient Greco-Roman world, the various levels of government often operated in a symbiotic relationship with local voluntary associations. In other words, the associations offered many people an entry point into a community of people who could pool their resources (financial, social, and otherwise) toward the greater goals of a guild, religion, social club, or city. From the evidence we have, it appears that most members of voluntary associations were male, though there are exceptions. It is likely that the earliest local “churches” would have been understood within this framework (as well as the framework of the Jewish synagogue) both by insiders—members as followers of Jesus—and outsiders.

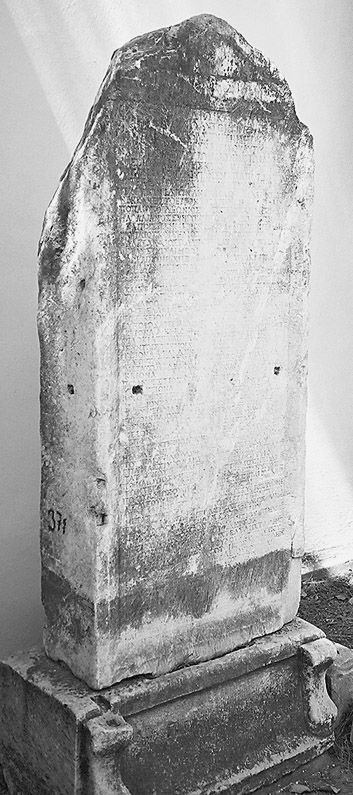

Figure 1.1. The monument erected by the fishers’ and fishmongers’ association in the 50s CE

There was an actual guild association of fishers and fishmongers at Ephesus in the 50s AD that was composed of people (along with their families) who represented a fairly wide spectrum of socioeconomic levels. They built a monument that celebrated their membership in the association as well as their work in building the fishery toll office. The monument lists approximately one hundred names that include Roman citizens (at least forty-three), persons free or freed from slavery (between thirty-six and forty-one), and slaves (between two and ten). The donors are listed according to the size of their contribution, with top donors first. The amounts range from the amount required to provide four marble columns to a sum of less than five denaria, or five days’ wages for a day laborer.

Her haze of grief was halted by the cry of Nikias. She stopped walking, her eyes searching for her son. There he is. His dark hair flopped over his equally dark eyes, and his small, naked body was crunched into a ball on the ground. She walked several steps back, to where he was sitting and clutching his bleeding knee. Bending over was awkward with her belly protruding, but she did so quickly, scooping him up while making soothing sounds. He insisted that she kiss his knee, and she did, wiping the blood from his olive skin with her hand and offering up a quick prayer of thanks to the gods for his health and vitality. Almost three years old, and so strong. His name was well chosen; he is truly victorious. Though Nikias insisted on being carried through the busy area, she set him down next to her and grabbed his little hand instead. “Your brother in my belly is taking up all of mommy’s space,” she told him. “Soon I will hold both of you, one in each arm. Soon, my little victory.”

They passed a shop displaying burial items, and her grief returned. She noticed the same type of tombstone that marked Dorema and her tiny daughter’s grave outside the city. After Dorema’s death, the midwife had followed accepted practice and cut the baby out of the womb. But it had been too late. The child was stillborn.

Dorema’s family had scraped together enough money to purchase the gravestone and pay for the engraving, though they had not been able to pay what it cost to commemorate Dorema or the baby properly. Anthia had done what she could; she had assisted Dorema’s mother and sister in washing, oiling, and wrapping the bodies. She had stood with family and friends at the wake, as Dorema’s body lay, her infant daughter next to her, with her feet pointed toward the door in the one-room home Dorema had shared with her husband, his brother, and his brother’s family. In contrast to the tears of the women, however, Dorema’s husband had stood stoically. Anthia knew that he was a man of few words and that he had not been affectionate toward his wife. Dorema also had not felt affection for her husband. She had simply accepted her father’s wishes and married the man of his choosing.

She shook her head to clear it and tried reminding herself of what everyone knew—that pregnancy and childbirth were dangerous, and everyone had friends and family who had not survived them—but it didn’t help. She was careful to keep her emotions veiled, however, and maintain her composure. A public display of grief would shame and anger her husband.

He was a good man, taking seriously his responsibility to care for her. Anthia was his second wife, his first having died in childbirth. She had heard that his first marriage was largely a product of his father’s wishes, though she did not doubt that he had cared for his first wife in ways that were similar to how he treated her. Their own marriage had been initiated by him; she had noticed his eyes on her during festival meals and in the agora, or marketplace, and she was pleasantly surprised when he had approached her father. They were social peers, sharing the same status, and the match had pleased families on both sides. At the time she had been fourteen years old, and he twenty-eight. She was ready for marriage and the responsibility of caring for a home, as her mother had trained her well. While Philetus occasionally hit or pushed her, she knew that it could be much worse, and she was grateful to be married to a man who did indeed care about and for her by providing for her needs. Their household felt secure to Anthia. They were doing their part for the honor of Ephesus, the province of Asia, and the Roman empire.

Marriage

In the Roman Empire a healthy household was considered to be the foundation for a healthy society. Marriage for nonelites (who comprised most of the population in the Roman Empire) was a family matter, not a governmental concern. This was due largely to the lack of money for a dowry or legal inheritance. In such situations the man and woman simply agreed that they wished to be married to each other, each stating “yes,” and their community accepted it. There were no prewritten vows or religious aspects. They would celebrate with friends and family and set up a home together.

A good wife was expected to be loyal in everything. Loyalty to one’s husband included being chaste until marriage, following his gods, obeying him, demonstrating modesty, not courting attention from other men, showing affection in bed to him as her only sexual partner, and allowing him to have other sexual partners without penalty. It was only adultery if a husband’s sexual partners included other men’s wives. The wife’s loyalty extended to her husband’s parents and family as well. There was a great deal of social pressure on wives to live up to these expectations, and most wives fell in line.

Social expectations for husbands included providing clothing and other necessities for their wives, teaching wives the family trade, and being discreet in their sexual liaisons. Physical and sexual abuse by husbands was common and socially accepted.

As they exited the agora, Anthia noticed a crowd gathered outside a nearby building. It caught her husband’s attention as well, and he signaled his intention to take a closer look. Public speakers and philosophers were common in Ephesus at lecture halls like this one, but this was an odd time of day for teaching students. Most teachers were busy in the early mornings, not during the midday break.

The group standing outside was silent, listening intently to the discussion inside. Anthia and Philetus joined them, and Anthia found herself standing on tiptoe to see better. The voices of two men emerged, and one had an accent that identified him as a foreigner. Where had she heard that accent before? The linen trader from Rome? The gladiator from Macedonia? she pondered.

The foreigner was talking about having hope after death. Hope after death? thought Anthia. What hope is there? My friend is lost forever to Hades. I will never see her again. Still, her curiosity about this hope overrode her better judgment, and she continued to listen.

The man’s dialogue partner apparently had the same thought, because he then asked the foreigner how there could possibly be any hope after death. The accented voice replied that resurrection was possible. He clarified that resurrection did not mean that one’s soul or spirit lived on but that a person would be brought back to life in a restored body. Body?! considered Anthia. Ridiculous. Everyone knows that dead people don’t come back to life, much less in their bodies. Again, the Ephesian man’s reaction mirrored Anthia’s, and he stated his skepticism of such an idea, asking how it could be possible.

The other man then told the story of a man named Jesus who had died and been brought back to life—resurrected—in a restored body. “Even if that happened, which I doubt, that does not explain how or why it gives hope after death for the rest of us,” the local man argued. “Paul,” he continued, “what kind of philosophy is this? I know of none that include this idea. All the philosophical systems I am familiar with do not value the physical body at all but prioritize the spirit and hope for it to be free from the body.”

Anthia nodded her head in agreement. Even she knew that much. The body was lesser, dirty, even evil. The spirit was what mattered. She inched her way forward, inserting herself between two other women who were watching, and saw the man Paul and his debate partner for the first time. Paul was not what she expected. Average, normal, she thought. He was probably five foot three, thin yet muscular, with a beard, and dark hair and eyes. Looks like most people around here. Actually, he looks quite similar to Philetus. Same broad nose and thick eyebrows. It’s just his accent that gives him away.

Paul’s next response only added to Anthia’s surprise and confusion. “The true god of the world,” declared Paul, “is the one who created all things, including humans. That god sent Jesus as the new man to show all of us how to truly live, and those who commit to Jesus and honor him with their lives will be raised into resurrected bodies as he was.”

“Who is this man Paul?” Anthia’s husband asked an acquaintance also standing outside the lecture hall.

“He is part of a movement called ‘the Way,’ a sect of the Jewish faith. He was teaching and dialoguing in the Jewish synagogue until his own kind kicked him out. He moved here, to Tyrannus’s lecture hall, and has continued promoting his crazy ideas.”

A Jew? That helped to explain the strangeness of what Anthia had just heard. She knew little of Jews, but she was aware that they oddly worshiped only one god. The Jews could not even see their god, as they had no statues or images of him. They also had unusual food laws, circumcised their baby boys, and had a lazy day once every seven days. But this, this resurrection idea was a new one. She’d have to talk with her neighbors about it later. Her friend Eutaxia would definitely know more details; she was always up to date on the news in the area.

Philetus nodded to her, and Anthia adjusted her grip on Nikias’s hand and followed. It was time to rest.

In the small room they called home, Anthia sat on the floor near the others who shared the space, including her father, aunt, and sister-in-law. Anthia pulled apart a small piece of dark, flat bread. She placed some in Nikias’s eager hand, then offered the rest to Philetus, who took it and tore it yet again. He shook his head, mentioned her belly, and handed a small section of the bread back to her. Anthia knew that the baby inside her needed some nourishment, so she ate the few bites. She dipped them in garum, a fish sauce. As she ate, she offered up a silent prayer to Poseidon’s wife, Amphitrite, the goddess queen of the sea. O Amphitrite, you who spawn all the fish of the sea, send a school to my husband’s nets.

Amphitrite could perhaps be persuaded by an offering or libation, though Anthia knew that the food or wine needed for such rites would be expensive. She and her family were hungry, but of course it could be much worse. They were surrounded by others in similar situations: friends, neighbors, and strangers who were focused on survival. A famine, a political crisis, a surge of new residents to their already packed insula, or apartment building—any of these realities, and others, could make it harder for them to sustain their lives.

Her eyes met those of her sister-in-law. Even after all this time Penelope’s blue eyes still caught Anthia’s attention. Penelope’s grandfather had been brought to Ephesus as a slave from a barbarian land, and her eyes and light hair were inherited from him. Penelope was also chewing slowly, savoring a few bites of the other piece of bread. Her two children ate hungrily, one at her breast and one sitting on the floor. The shared glance communicated volumes. Both women knew there was nothing they could do in that moment to provide more food for their children. Anthia glanced next at her father and aunt, who were both sitting in their favorite corners on bedmats. Neither was eating, and the reason was clear. There was not enough food to go around. At least Penelope’s husband, Andrew, wasn’t here, as he would simply be another mouth to feed. Andrew worked as a day laborer in the harbor and rarely returned home midday.

Finally, Anthia cleared her throat. “How was your morning, Penelope?” She was almost afraid to ask but felt she needed to do so. The quick shake of Penelope’s head told her everything she needed to know. It was the season of harvest, and these days Penelope spent her mornings outside the city, attempting to glean whatever wheat, barley, beans, or lentils she could from already-harvested fields. Her task was complicated by her need to nurse her infant, who cried constantly and was quieted only when nursing. She usually wore him, wrapped near her breast, to keep her hands free. The toddler had been staying behind with Anthia’s father and aunt, but her father was old and frail. It was often her aunt, Eirene, who cared both for Anthia’s father, Demas, and the toddler while Penelope was in the fields.

Poverty and Subsistence

New Testament scholar Steven Friesen has famously proposed a seven-tiered “poverty scale” for the free (i.e., not slave) population of the Roman Empire.a Others have modified and nuanced his work (including Bruce Longenecker), but the basic paradigm is still helpful.b Perhaps the top 3 percent of the Roman empire was part of the social elite and lived well above any ancient poverty line, with access to a great deal of excess of whatever resources (including food) they desired.

The rest—97 percent—of the free population was spread across a wide range in terms of access to food and other necessities. The top percentage of this large majority would have had access to some surplus that would have helped them to survive famines and other shortages. Perhaps traders, veterans, some farmers, merchants, and artisans would fit this category, and their numbers are estimated anywhere from 7 to 17 percent.

The bottom 80 to 90 percent of the population lived just above, at, or below the subsistence level, with subsistence defined as the minimum needed to sustain life. Farm families as well as some traders, shop owners, laborers, small-scale merchants, and artisans would have lived at the top and middle of this group, with prisoners, the disabled, unskilled day laborers, beggars, and unattached orphans and widows at the bottom end.

While Anthia reached for a plain ceramic cup, she considered the bowl that sat next to it, which during times of plenty was often full of barley soaking in water. The soaked barley would then be used to make porridge or the chewy dark bread they often ate. At least they had enough water to drink; there were lead-pipe open aqueducts in the city, some of which brought water from rivers that were miles away. There was also a spring, the Callipia, inside the city, and fountains throughout, one of which was nearby. Anthia knew that the elite terraced apartments near the lower agora each had water funneled to them through an elaborate and costly system. Their own insula did not have such a structure, but she was content to carry water from the fountain up the stairs every day.

She heard a child cry. Euxinus, she thought, and smiled, recognizing the sound of her friend Eutaxia’s son next door. They lived on the top floor of a multistory insula, and the walls were thin. Their area of Ephesus was filled with insulae, which housed laborers of all kinds, artisans, small-shop and tavern owners, and various merchants and traders. Some higher-status people also lived in insulae, though they often lived in several rooms, not just one, like Anthia and her family. It’s not that crowded, she told herself. There are only nine of us in this room. Well . . . ten, counting you. She patted her belly.

She laid Nikias down on the small mat in one corner, taking her place next to him. Philetus quickly joined them, and Penelope copied the action, lying down nearby with her boys. Anthia looked toward her father and aunt, but they were already resting. She listened to the noise of the neighboring apartments; Eutaxia and her husband were arguing again, and the new baby in the room below them was crying. A goat bleated from somewhere, and a child was singing. She dozed, only to be awakened by the sharp kick of the baby inside her. She touched her stomach. Baby, all is well. Rest. The kicks continued at a furious rate. Smiling, she added, You must be a boy. A strong, healthy boy. Artemis, great goddess, please smile upon me and shape the form of this child in my womb to be male. Please. Knowing that she had work to do, she struggled to sit up, though the size of her belly impeded quick movement.

As she stood, her foot accidentally kicked the ceramic cup she had used earlier, and it broke into several pieces that scattered on the floor. She sank to her knees and began to scoop up the shards with her fingers, but Philetus’s backhand on her cheek stopped her. Half kneeling, she paused before giving the expected response.

“So sorry. This is my fault, and I will fix it.” She waited, not daring to touch her stinging cheek in front of him.

“Clean it up and come.” She did so, making sure to pick up each fragment. Grabbing Nikias from his mat, she managed to snatch her cloak as well before she moved toward the door with her husband.

They walked down the flights of stairs that led from their insula to the street, with Anthia doing her best to hide her red face from those they met on the way. Once outside, she adjusted her cloak to cover her head and face.

She walked quickly, matching her pace to that of her husband. The smell of sewage intensified as they neared the public latrines, though the streets always smelled of both human and animal excrement and urine. They passed a man relieving himself on a wall, and he stumbled backward, narrowly missing them with his stream of urine.

Near the agora they again walked past the lecture hall of Tyrannus. The crowd outside was still there, and even from a distance Anthia could hear the agitated voices.

“Paul, you insult me! Surely no educated man in Asia could believe such nonsense! You say that the one true god of the world has appointed this man Jesus as judge over all of us and that his resurrection is proof of this?”

Paul’s response was equally passionate. “Yes! And the appropriate response is repentance, which means giving up our own agendas and priorities and living as this god created us to live!”

Anthia and her husband passed behind the crowd silently, listening to the heated debate. Philosophical debate was nothing new in Ephesus; to the contrary, it was a valued activity and showcased the education and status of its participants. What was new was the content. Resurrection? Repentance? Judgment? Though he was clearly educated, perhaps the mind of that man Paul was not healthy. That must be it, Anthia assured herself. He’s unwell. She found that she was still listening, however, even as the voices faded. Well, that’s that, she concluded. No more of Paul.

Back in their fishmonger’s stall, Philetus conferred with a few other men and left with them to fish. Anthia watched them go, wondering where they would fish and which gods they might petition on the way. She settled in with the other women, glancing up at their few small fish that had been hung to display them to anyone interested in buying or trading.

A few hours later, Philetus had returned, and Anthia followed him out of their fish stall and into the market, grabbing Nikias’s hand on the way. The women had successfully traded the fish for some olives and chickpeas. At least we’ll have something to eat tonight, she thought, even though the men did not catch any new fish this afternoon.

And then a familiar voice caught her attention: “Yes, of course! Priscilla, Aquila, we can manage that, don’t you think?”

Startled, Anthia turned her head to see the man Paul from the lecture hall. He was standing in a small shop with another man and woman, and they were holding what appeared to be leather of some kind. She heard his accent again as he continued talking with a third man, who was clearly a potential customer. “Hippothous, we will make this tent for you. And won’t you eat with us this evening as well?” Hippothous’s reply was too quiet to hear, but Paul’s response was not. His laughter filled the air, and he clapped his customer on the back. “That is true, but it does not matter. We can still eat together, and Aquila and Priscilla will be there as well. Jesus, whom we worship and honor, shared meals with people from varying status levels, and we do the same.”

Shocked, Anthia continued to walk next to her husband. She glanced at his face, but he apparently hadn’t overheard the conversation. Eating with people who outrank you? Or whom you outrank? What can he be thinking? wondered Anthia. Who does such a thing? And why? She pondered the question of whether Paul was trying to gain honor by eating with someone from a higher status than him. Could that be it? Then Paul’s answer came back to her: Jesus. Paul had said that he eats like Jesus ate. Jesus was also the one Paul had said was raised from the dead, so Anthia knew that she couldn’t trust what Paul said. But maybe tomorrow she would listen carefully as she passed the lecture hall and the shop; perhaps she could discover more. At the very least, it was good gossip.