The Pacific War was dominated by the sea, and practically all troop movement was by ship. The pre-war aircraft were not capable of carrying any worthwhile load over the huge expanses of water and jungle that are such a feature of the Far East. However, it was always realized that because of these distances quite small bodies of troops could exercise an influence out of all proportion to their numbers, could they but get to the right place at the right time. Ships are slow; overland movement through jungle had to be at walking speed in most of Asia until long after 1945; and the few vehicle roads were easily blocked and watched from the air. The one way of moving troops that offered some freedom from the restrictions of the terrain was by using the new airborne techniques – if only there were aircraft to lift them. If, in 1941, there had been an airborne army in Japan on the scale of the German one, and with the aircraft to carry it, then the whole history of the Pacific War might easily have taken a far blacker turn for the Allies right from the beginning.

It is interesting to speculate now on how quickly and easily the Japanese could have pinched out island after island by dropping a parachute battalion into the coast area, seizing a beach-head, landing the follow-up force; and then rolling up the defence in one movement. Alternatively the parachutists could have landed on the usual island airfield as the seaborne landing came in, and destroyed the defending planes before they could get into the air. The possibilities are endless: what, for instance, might have been the effect if the attack on Pearl Harbor had been accompanied by a parachute drop and then an air landing?

At the start of the Pacific War the only airborne force in the Far East was the Japanese. (Its birth and rise are told elsewhere.) Like all the other airborne forces, with the exception of the Germans, it was hampered by a lack of suitable aircraft and was constantly struggling to justify its requirements against those of the logistic needs of the army. All too often the latter had priority and the tactical force had to wait, and even when the planes were made available, they were often too few in number and could not be used to fly in a follow-up force. So the Japanese never had the chance to use their airborne troops effectively, which was perhaps just as well from the Allied point of view since there were too few British and American troops in the Pacific in 1942 to be able to offer much resistance to properly mounted and co-ordinated air and land assaults. A few operations like that carried out in Crete would have had a shattering effect on the Allied plans which they might have taken years to get over.

As it was, there were 16 airborne operations of one kind or another in the Pacific area from the time of Pearl Harbor until the Japanese surrender. Most of these were relatively small, but one or two were quite large, though never on the scale of the huge divisional and corps operations which took place in Europe. The Pacific could never muster either the men or the machines for that size of air battle, and the emphasis remained on seaborne landings. Once the style of the war had settled there was little sense in changing it to another technique altogether, so the airborne arm remained very much a secondary weapon except for the Chindits’ long range raids, where air support and air superiority were vital.

The first uses of airborne troops were by the Japanese in the attacks on Java, Sumatra and the Celebes Islands at the very beginning of their widespread invasions. The first operation was a satisfying success; it was the capture of the airfield at Menado in the north-eastern tip of the Celebes. The airfield was held by a small force of Dutch regulars with a much larger force of not very good local native units in support. On 11 January 1942 the airfield was heavily bombed and strafed immediately afterwards by fighters. Before the defenders had time to fully recover, the parachute force arrived and dropped without interruption. The force consisted of three companies of the naval parachute troops and they were dropped without any heavy equipment, but with some air support in the shape of more fighter sweeps. The native defenders fought reasonably well until it was obvious that the Japanese were winning, and then they fled. The small Dutch unit fought with great heroism and tenacity, but was almost wiped out, and the few survivors surrendered.

The battle had taken five hours and although the Japanese casualties must have been heavy – there is now no record of how many men were lost – the result was worth it. It was a good use of the parachute arm, and the effect on the morale of Allied troops in the area was considerable.

Three days later there was another, similar type of attack. This time it involved much larger numbers of troops and aircraft, but was less well co-ordinated. The lack of co-ordination may have been due to the distance from the launching area for the target was the airfield and oil refineries at Palembang in Sumatra, and the nearest Japanese-held airfields were either in Singapore, 300 miles away across the Straits of Malacca, or in Borneo which is even further. This long distance may also account for the absence of fighter strafing before the drop, for the only preparatory air action was a high level bombing attack during the day. The parachute drop did not come in until 1830 hours, by which time the garrison was fully alert and expecting an attack. The 70 aircraft flew in two waves straight over the anti-aircraft guns heading for a dropping zone about 5 miles away. Anti-aircraft fire forced them to scatter and drop high and the men were spread around the dropping zone area to such an extent that it took several hours to mount the assaults on both the airfield and the nearby oil refineries. The airfield was attacked by 300 men, and when they failed to capture it a further drop of parachutists was made the next day to reinforce them. They then succeeded, but the oil refineries were held until the Dutch could completely destroy them. It was more than a year before they were back in action. The Japanese lost over 200 men and 16 aircraft in this episode, partly owing to lack of preparation, partly to a complete lack of air support for the parachutists, and partly to an underestimation of the expected resistance. But they gained the airfield, and defeated a force three times their size. It was a good start.

A week later, on 21 February, the Japanese launched another parachute assault, this time on Timor. The lessons learned following the attack on Palembang had obviously been carefully studied because there was first of all a feint attack by five loads of parachutists on to a position some miles away. The main attack was to establish a block on the Allied lines of communication, and this was preceded by heavy ground strafing which continued until the 350 parachutists were on the ground. The operation was completely successful and was followed up the next day by a seaborne landing which overran the island. This was a proper use of the lightly equipped parachutists which the Japanese possessed, and was an encouraging note to end on. There were no more Japanese parachute assaults until the middle of the following year, by which time the technique had been largely lost.

The next attempt to use airborne troops in the Pacific was by the Allies, and it was an air-landed operation. Wau, in New Guinea, was an outpost for Port Moresby. On 28 January 1943 it was under heavy pressure from Japanese troops and the only way to get in reinforcements was by air. Next day 57 Dakota sorties scraped in under the clouds to land on the tiny airstrip and disgorge two battalions of Australian infantry. More followed over the next two days, and even guns were flown in. The strip was under continual small arms fire, and the first sorties found it easier to keep rolling along as the troops jumped out as this made it more difficult for the mortars to score a hit. The infantry went straight into action as they landed, many of them firing from the moment they left the aircraft doors. The strip was only 1,000 yards along, and the far end was 300 feet higher than the near end, so all planes landed uphill, turned at the top, and immediately took off again downhill. There were no crashes, which speaks volumes for the skill and coolness of the young American pilots. This neat little operation turned the tide of the war in New Guinea and started the long haul from island to island which slowly rolled the Japanese back northwards.

Meanwhile the Japanese were still advancing in other areas and in August 1943 they were pursuing the Chinese Nationalist Army in Hunan. In a well planned small operation a blocking force of 60 men was dropped to cut a road, and having done so, it was quickly relieved with very light casualties. This was the only Japanese airborne operation in 1943, the main reason being that the small air transport force was fully occupied in supplying the very widespread fighting zones in the Pacific Theatre. In fact, the Japanese were now at full stretch, and finding it increasingly difficult to hold on to what they had conquered. The pressure was mounting, and it was increased with the next Allied airborne attack.

The relief of Wau led to a general counter-attack in New Guinea and the first major objective was the town of Lae on the north coast, and the flat land in the valley of the River Markham, which ran into Lae. This valley was one of the few places in northern New Guinea where airstrips could be quickly and easily built, and the next stage in the drive towards Japan was going to need the maximum possible air cover. Speed was essential and Lae was to be taken by a seaborne assault backed up by a large parachute drop in the Markham Valley behind the town. There was intensive preparation for this drop and nothing was left to chance. The troops were from the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment, who had last jumped in North Africa 18 months before, and they were taken to Australia for complete rehearsals. Shortly before the drop they were joined by a troop of the 2/4 Australian Field Regiment who were to go in with them. These men had practically no rehearsal at all and were rushed through a one-jump training course before being sent off on their first operational drop! Their 25-pounder guns were equally rapidly converted to air-dropping and were carried in bundles under the Dakotas. The gunners were made parachutable inside two days, an extraordinary performance, all the more so when one remembers that the 25-pounder had never been dropped by parachute before, and the method for the drop was worked out on the airstrip by the ground crews.

The Markham Valley drop must have been a clear indication to the Japanese that the scale of the war in the Pacific had changed. Of the 302 aircraft which took part in the drop, 96 carried a total of 1,700 parachutists; the remainder were bombers, fighters and follow-up transports carrying supplies and ammunition in under-wing bundles ready to be dropped once the objective was secured. The valley was taken with very little opposition, and immediately the engineers began building the first fighter strip. From then on the main effort in the Pacific went into seaborne assaults and the transport aircraft were fully committed to simply being load-carriers; but it was obvious that when the need arose the Allies could now mount a very substantial combined air assault which made the earlier Japanese efforts look rather second-rate.

It will now be convenient to jump a year in the chronology and look at the next airborne operation in the New Guinea area. This occurred ten months later on the island of Noemfoor, just off the western tip of New Guinea. The Japanese had built airstrips on Noemfoor and these were needed by the Allies to extend their blockade of the Japanese supply routes to the south and west. The plan was to capture the main Kamiri airstrip on the island by a surprise amphibious assault, and to reinforce this bridgehead by dropping the 503rd onto the strip. Because the strip was short and narrow the lifts would have to fly in line astern, and the release point would need to be precisely fixed. Three lifts were needed, and it was decided to drop one on each of three successive days.

The amphibious assault went well and the strip was secured. The first lift of the 503rd flew in and it became immediately apparent that there were dangers in not holding proper training and rehearsals. The pilots were unused to dropping parachutists and flew too fast and too low. The navigators missed the release point and men were dropped at all heights from 200ft upwards on to, into and around the dropping zone. There were many injuries, partly from the concrete-like surface of the airstrip, partly from the many obstacles still littering the runways, partly from landing in tall palm trees and then falling to the ground and partly from dragging in the strong wind. Next day the second lift dropped with casualties again, and the third lift came in by sea. The regiment then took a leading part in the heavy fighting to clear the island, which continued for the next six weeks. It is difficult to see why it was considered essential to fly in the reinforcements for an amphibious assault which had gone so well, and which had a beach-head where men could be landed, but perhaps it was thought that parachuting would be quicker and easier, and perhaps landing craft were scarce in that area.

The biggest airborne operation of 1944 was not in the Pacific area at all, but in Burma. This was the special forces operation in the rear of the Japanese Army, Operation Thursday as it was correctly called, the ‘Chindit’ Operation as it is more popularly known. Originally General Wingate had intended to train his Chindits as parachutists, dropping them into jungle bases in a fairly random pattern, but the amount of training required dissuaded him from this speciality, and he settled for larger bases with airstrips where he could air-land his forces. He was immediately much restricted in the choice of base because it had to be sufficiently remote from the nearest Japanese units to allow aircraft to land without interference and build up a defensive force. Parachutists could have dropped in, seized an existing airstrip, held it and been reinforced by air-landed troops in the way the Germans had done so successfully in Europe. Without the parachutists the initial danger period after the arrival of the first aircraft became much longer and more acute. It was not possible to capture a working strip, so it became necessary to build a strip in a clearing and, to build the strip, heavy plant and equipment were needed. These could only be taken in by glider, and there were no gliders in India.

Wingate was extremely fortunate in being supported in his theories by General Arnold, Chief of the US Army Air Corps. Arnold saw to it that Wingate got what he needed in the way of aircraft, and he formed a special unit for the Chindit operations; No. 1 Air Commando. This was quite independent of the rest of the Air Corps, and was under the command of an intensely lively and energetic young colonel, Philip Cochran. Among the aircraft that Arnold approved for the Commando were 100 Waco CG-4A gliders, which were shipped in crates to India. Wingate’s outline plan for the fly-in of his troops could now be made; suitable jungle clearings were to be chosen into which his force of gliders could land by night, carrying pathfinders and a small force of infantry for local defence. The pathfinders would guide in the next wave of gliders carrying the bulldozers and the engineers to work them, and then all efforts would be directed to making an airstrip suitable for the Dakotas to fly in and out. This might take a day or two, during which the whole operation would be vulnerable to a Japanese counter-attack, hence the need to be far enough away from the main routes and garrisons. But Cochran could ensure that there was plenty of close air support on call to the defenders.

There was a great deal of training in the weeks before the operation, not least by the Air Commando who experimented with casualty evacuation by light aircraft, close air support controlled by RAF observers with the forward troops, and also double-towing of gliders. Double towing was a favourite idea of Wingate’s as he was short of Dakotas, and needed to get the greatest possible loads flown in with each sortie. In the event it was found that it was undesirable to double-tow above quite low heights, and the planes which had to cross the mountain range between India and Burma had difficulties. However, much valuable experience was gained, particularly in night towing and night glider landings. Early in February one of the ground columns was backed up with glider landings when the columns reached the River Chindwin, and bridge material was flown into it. It was here discovered that gliders could be put down on quite small areas, provided that they were clear of obstacles, and that supplies could be dropped into clearings no longer than 60 yards and less than 20 yards wide.

The full story of Operation Thursday is too long to recount here, and it has already been told in great detail elsewhere. The airborne aspects of it are the main concern of this narrative, and the tactical side will be ignored for the sake of brevity. Three main sites were chosen for the first assault. Two, code-named Piccadilly and Broadway were to be used on the first night. Twenty-four hours later the third, Chowringee, about 40 miles away, would be taken. All three were to be attacked by glider assault, and due to the shortages of tugs all three assault lifts would go in on double tow. Broadway and Piccadilly were to have 40 gliders on each, in successive waves.

Just before take-off of the first lift, at 1630 hours on 5 March 1944, a last-minute reconnaissance showed Piccadilly to be blocked with felled trees. Wingate immediately shuffled the glider loads, changed the lifts, and sent 60 gliders to Broadway instead. An hour was lost in doing this.

There was now a danger of ground opposition, or so it was thought, but in the event there were no Japanese on the landing zones and the gliders came in safely. There was an interesting variation in the technique of landing. The first wave was released high and came in on a normal approach and touch-down, but the subsequent waves were released at a very low height just short of the end of the strip, using a pathfinder light to mark the release point. They then flopped down as quickly as possible, the idea being not to expose them to small arms and anti-aircraft fire while in the air. It was soon found that there were drawbacks to this system.

The first waves landed easily, but the second waves, which were the ones released low down, could not lose speed quickly enough and two crashed and blocked the runway. Another pancaked on top of them, killing two men. The strip had to be closed for the night and all other gliders turned away. Chowringee was an easier task to prepare. The engineers’ equipment was flown to the area in 12 gliders, and the landing interval between the gliders was doubled with the result that there was only one crash, which destroyed a bulldozer. It was replaced with one from Broadway, using a glider snatch to get it out. Snatching had only recently been invented and practised, and only light loads had been tried, but the need was urgent and it was found that there was little trouble in picking up a fully-loaded glider, though to try it out in a jungle clearing for the first time must have taken cool nerves.

Of the 61 gliders which took off from India, 35 landed on Broadway, three of them crashing; eight were recalled and landed back without trouble; four broke loose just after take-off; four were brought back because their tugs developed engine trouble; eight landed in enemy territory in Burma; and two were released short of Broadway and crashed into the jungle. Of the eight which landed in Burma, four crews walked out, two crews were captured and two crews disappeared altogether. Of the two gliders which crashed near Broadway, only two men survived. But the 35 gliders which arrived on the strip delivered 400 men, and there were no ambushes and no opposition. The strip was ready for Dakotas by the next evening, and the first one landed at 2000 hours. The build-up had started.

Further strips were built in Burma during the next two months, and the Japanese found themselves faced with substantial enemy bases in their rear areas. They reacted as they were expected to, and wasted much effort and lost many men in attacking these well defended fortresses, but it could not go on for ever. All the bases were utterly dependent upon the air for their supplies, reinforcements and casualty evacuation, and the Japanese quickly mounted heavy strafing attacks on them. It then became necessary to give fighter cover to the Dakotas and the strain on the depleted RAF and US Army Air Force became too much. At the critical time when the impetus was disappearing, General Wingate was killed in an air crash and the entire operation slowed down. On 20 May No. 1 Air Commando was withdrawn to rest and reorganize and the operation was officially declared over on 25 May. It had served its purpose, and shown that large forces could be inserted behind enemy lines and supported for long periods, provided that the conditions were right, and provided that there was sufficient air support of all kinds to sustain and protect the ground troops. But without air supply and without air support such long-range operations could not succeed, and any attempt to put down strong points and permanent bases would have been suicidal.

Historians will dispute for years whether the Wingate operations were sufficiently valuable to justify the effort and the casualties, and it is very easy to criticize when one has hindsight to see the whole picture. At the time it was important to strike back at the Japanese, and to strike back hard. The Japanese could be hurt most by being attacked where they least expected it – in their rear areas – and for that the Wingate methods were ideal. We now know that in the long run the Japanese were not particularly disturbed by these intrusions, but they lost large numbers of men trying to remove them, even if their front-line units were not affected. For the Allies, much useful information about glider operations was gained, and the effect on morale was considerable. On balance it must have been worth it.

In the final acts of Operation Thursday a small force of Indian parachutists was dropped near Mogaung with specialist flame-thrower equipment and a medical team, a rare use of parachute troops in Burma.

After Operation Thursday the fighting in Burma returned to the ground units and there was only one other active use of airborne troops before the end of the war. It will be convenient to deal with it here in order to complete the story of the Burma fighting. In May 1945 the Japanese had been pushed southwards through Burma and were falling back on Rangoon. The city lies 24 miles up a winding river, well supplied with shifting sandbanks and similar navigational hazards. In addition there was known to be a gun-battery at Elephant Point, where it could dominate a difficult part of the river, and where it was virtually immune to an amphibious landing. By far the best solution was to take it by a parachute assault. A mixed battalion of Gurkha parachutists was made up, there being no formed units available, and was quickly rehearsed. On 1 May the battalion flew in and dropped in two lifts on to a dropping zone 5 miles from the objective. It had a difficult approach to what turned out to be a largely empty enemy strong-point. It was a sad anti-climax to a strenuous and exciting build-up.

The centre of interest now swings back to the Pacific proper where the war was moving into its last stages. By the middle of 1944 the Japanese were on the defensive and being steadily pushed back, island by island, towards Japan. Neither side used airborne forces, though the US 11th Division arrived in the theatre in May 1944, and kept itself in training for air operations, but it was mainly used as another infantry division. The Japanese had lost command of the air and had too few aircraft for large or sustained airborne assaults and they were forced to confine themselves to what amounted to minor raids. Early in August a few aircraft successfully dropped some agents by night and on 26 November 1944 three aircraft flew over Leyte Island, which was in US hands, to drop parachutists. These men were to sabotage the aircraft based on Leyte so that a Japanese reinforcement convoy could get through to Ormoc Bay two nights later. One plane was shot down before it reached the drop zone and all the parachutists were killed. The other two tried to drop on to the drop zone but were so harried by anti-aircraft fire that they scattered their sticks all over the island and were then both shot down. None of the parachutists succeeded in reaching a single US plane, and all were eventually hunted down and killed.

Ten days later the Japanese repeated the disaster on a larger scale, again with the intention of disrupting US air attacks by destroying the planes on the ground. It is a measure of the desperation of the Japanese command that they were even prepared to consider such a suicidal idea, much less actually try to carry it out. By this time in the war there were virtually no Japanese pilots who had dropped parachutists, nor was there any hope of much rehearsal. Once again the target was Leyte, this time the targets were three airstrips which were to be assaulted in conjunction with a seaborne landing in Ormoc Bay. The parachute troops came from one of the special raiding regiments and the aircraft were originally a raiding flying regiment.

The troops had had fairly extensive ground training for the operation, but it is unlikely that the air element was fully effective and the intelligence was poor. Two of the objectives were disused airstrips, and the men were wasted; the third was not fully operational and only held light aircraft, a fact that could have been established by air reconnaissance before the drop. Another fact that would have come to light was that the area was well filled with troops, in fact the US 11th Airborne Division was actually responsible for the ground on which the dropping zones were planned. On the night of 6 December the airstrips were bombed from high altitude and shortly afterwards two tight formations of Japanese-built C-47s flew across the strip, in two large vees at about 700ft. Many of the 300 men dropped were killed before they reached the ground. The remainder landed in widely scattered groups and took time to assemble, using an odd selection of gongs, whistles, clappers, musical instruments and even songs to assist themselves. The amazed Americans stayed in their foxholes and shot down anyone who moved. It took them two days to clear the strip, but little damage was done, and within six days the last Japanese was rounded up. The seaborne assault failed, and a co-ordinated attack from the Japanese 26th Division in the mountains of Leyte failed too. The net result of it all was that the US air supply to some of their forward troops was interrupted for a few days, and a number of US troops were casualties in the fighting. The Japanese lost all 300 men and 18 of the mixed force of 51 bombers and transports were shot down. It was the last attempt by the Japanese to use parachutists, and should never have been tried. Without the necessary air strikes to support the parachutists on the ground, it was hopeless to expect them to be able to make any impression on a strongly held island. The Americans did the most sensible thing and sat tight, letting the Japanese do all the attacking, knowing that they could not be reinforced and would quickly run out of ammunition, food and energy. And so it came about.

The 11th Airborne Division now took part in the invasion of Luzon, the major island of the Philippines group, and its one parachute unit, the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment, was dropped on three occasions. The first time, on 2 February, the 511th was dropped as a reinforcement, but lack of training on the part of the pilots and a misjudgement of the drop zone by several aircraft caused a very scattered drop and some injuries. On 23 February a company was dropped on to the Los Banos internment camp in a surprise drop at dawn; they overpowered the guards and released the internees within half an hour and a follow-up column of amphibious vehicles evacuated the lot. It was a neat little operation, quickly laid on and carried out without fuss; a good example of a sensible use of airborne troops. Unlike the disastrous Japanese raids of the months before, this one was helped by careful and precise reconnaissance coupled with complete air superiority. The US lost 6 men, the Japanese 247, and one internee was slightly injured.

The finale of the airborne soldiers in the Pacific took place close to Manila, on the island of Corregidor. By the middle of February the Americans were advancing from north and south against Manila, and as soon as Manila was captured the port was going to be needed. But the entrance to Manila Bay was guarded by the island of Corregidor, a massive tadpole-shaped rock rising sheer out of the water, honey-combed with tunnels and bristling with guns. Indeed the Americans had quite deliberately laid out the defences on the lines of a huge battleship, and the gallant and historic defence conducted by General MacArthur in 1942 showed very clearly how impossible it was to take it from the sea, or to destroy it by bombardment. The Japanese had put a garrison of 6,000 men on Corregidor, though the US Army was misled into thinking that there were only 850, and it was obvious that special measures were going to be needed if the island was to be taken by assault. From 23 January onwards Corregidor got a daily pounding from the US Air Force to soften it up while the final plans were laid.

Corregidor is so small that there were only two possible dropping zones which were not actually overlooked by pill-boxes. These were a tiny golf course and a nearby parade-ground, both on the topmost height of the island. Each was about 250 by 150 yards which meant that the sticks would have to be very short, and the under and overshoot areas were bounded by 400ft high cliffs down to the sea. To make matters worse there was a constant wind blowing over the top which rarely fell below 15 knots. This meant that there would have to be a very carefully calculated offset in the release point to get the first and last men onto the drop zone. Only one plane would be able to drop at a time, and each would need three runs over the drop zone to clear the full load of paratroopers. The flight plan called for each machine to fly in turn, and between turns to circle in a stacking area. Each jumpmaster was flown over the drop zone and allowed to have a good look at it before the jump, and the operation was controlled by a command C-46 which circled overhead throughout the drop, radioing corrections to each plane as it flew in. Only 51 C-47s were available for parachutists, which meant that only one battalion could be dropped at a time. It was therefore planned to drop the first at 0830 hours on 16 February, the second at mid-day and the third the next morning. No weapons containers were to be dropped, to speed action on the drop zone, and so the mortars and machine guns were broken down into individual loads and a piece carried on every man. A battery of 75mm guns was to go in with each lift, this being the only exception to the ‘no-containers’ rule.

Bombers continued to hammer Corregidor, flattening all the barrack buildings around the parade-ground dropping zone. On the 16th the troop-carriers took off at 0730 hours carrying the 3/503, and as they approached the island a final bombardment was just finishing. Dropping began at 0800 hours at a height of 600ft and in a wind speed of 18 knots. Some of the first load were carried over the edge of the cliffs, though they did not fall into the sea, so the regimental commander in his airborne command post ordered the remaining planes to come down to 500ft, and the jumpmasters to count six after the green light; this put the majority on to the drop zones and the troop carriers droned round and round in a steady deliberate fashion that would have been fatal anywhere else. But the Japanese were below ground and were not expecting such an apparently suicidal attack. They could only bring a few small arms to bear and these caused no trouble to the planes and few casualties to the parachutists. The surface of the dropping zone was badly broken up by the bombing and there was a good deal of wreckage lying about, the 18 knot wind left little margin for error and about a quarter of the force was injured on landing. The remainder wasted no time in clearing the bunkers and pill boxes that had survived the bombing and setting up their guns to cover the amphibious landing. By 0930 hours the last man was down and the planes went back to collect the 2/503. As they left the seaborne assault went in and was successful. At noon the troop-carriers returned and dropped the 2/503 in a freshening wind, but this time there were fewer casualties on the drop zone, largely because there were friends about to catch the canopies of draggers.

The island was now clear on the top, though the entire Japanese garrison still survived underground, but the job of the parachutists was done and it was decided to cancel the reinforcement drop by the 1/503 and bring the battalion in by sea. It then took ten days of bitter and unpleasant fighting to clear all the Japanese which cost the 503rd a further 850 casualties. Only 27 Japanese prisoners were taken out of the 6,000 defenders.

Corregidor was a prime example of the value of a small airborne force of determined men, backed up by adequate air support. Without the parachute drop the amphibious landing would have been enormously costly, if not altogether impossible. It was exactly what the island was designed to prevent, and it is just possible that the Americans might have had to try some other means of attack such as poison gas or in the last resort, starvation. As it was, heavy preparatory bombing cleared the way for the drop and the drop cleared the way for the landing. It was almost like a larger version of the German assault on Fort Eben-Emael, where the problems were very similar. The meticulous planning was also very similar, and it is probably no accident that both operations were successful.

By June 1945 Luzon was almost all in American hands; only the extreme north-east was still Japanese. Here the enemy was in full retreat towards the port of Aparri, where he hoped to make his escape. There was a need to seal off Aparri and bring the campaign to a decisive end. A battalion-sized task force was made up from the 11th Airborne Division and dropped close to the port. Over one thousand men took part and the heavy equipment was flown in using seven gliders – the first time they had been used in the Pacific. At 0600 hours on the 23rd the task force took off from the same airfield that the Japanese had used when they launched their unhappy attack on Pearl Harbor on 6 December. Precisely at 0900 hours the first plane started to drop, and by 0915 all were on the ground. The wind was 20–25mph which brought about several casualties, but the landing was unopposed and three days later the last Japanese was cleared from Luzon. There were no more airborne operations in the Pacific Theatre, and in early August the dropping of the atomic bombs on Japan ended the war.

In summing up the work of the airborne forces in the Pacific it is difficult to avoid leaving the impression that they were unnecessary and a luxury that was nice to have around, but not one which was strictly necessary to win the war. The Japanese showed that with proper planning and careful execution airborne forces were every bit as effective in the Pacific as in Europe, and had they carried on with their attacks through Java and into New Guinea it is perfectly possible that they could have taken Port Moresby, and so cleared the Allies out of New Guinea altogether. Whether they could have sustained any further-ranging attacks is doubtful, though a quick raid on Darwin would have shaken morale in Australia. One is left with the firm impression that the Japanese lost a superb opportunity in not fully exploiting their airborne forces, the more so since by early 1942 they had shown that they had mastered the elements of successful operations.

For the Allies, it is a matter of regret that the 11th Division spent an entire year in theatre before being used at all, and then not decisively until the very end. The astonishing Corregidor operation inevitably causes one to wonder whether the same technique might not have saved thousands of American lives in expensive seaborne landings on the island ‘stepping-stones’ towards Japan. But the Pacific was a sea-dominated war, and in the minds of the commanders transport aircraft were for carrying supplies and not for fighting battles.

As with so many of their projects, when the Japanese started to organize parachute troops they did it thoroughly. In the early part of 1940 they set up four training centres at Shimonoseki, Shizuoka, Hiroshima and Hileji at which they ran courses lasting six months. Not surprisingly, the output from these courses was low and German help was called for. Four German instructors arrived in the summer of 1940 and recommended reducing the length of the courses to two months and intensifying them. These early courses had used a scratch collection of equipment to which was allied a very poor appreciation of the requirements of a parachute force. As a result the few manoeuvres which were tried were not at all impressive and there were disturbing numbers of casualties. From the summer of 1940 onwards there was a greater and greater German influence in the training and use of the parachute force, although the Germans failed to persuade the Japanese High Command to see that airborne troops could operate successfully on their own.

With the Germans came improved equipment; the standard Japanese parachute was modelled on the German RZ series, with the same limitations in the way personal equipment could be carried, and the same difficulties for the men on landing. By the autumn of 1941 there were about 100 German instructors in Japan working in nine training centres and over 14,000 men in training. This number was split between the army and the navy as both had their own independent airborne units and their own training arrangements. Of the two, the army training was the more thorough and, on the face of it, the safer. Army training was split into five stages, with an assessment at the end of each stage. The general outline followed that of any other training syllabus with great emphasis on physical fitness and running. Stages two and three taught parachute folding, packing and maintenance, stage four was tower jumping and in stage five the men jumped from aircraft.

The naval course was much shorter, the first ones lasted for only three or four weeks, and it was soon found that the men were dangerously under-trained. The course was then lengthened and became very similar to the army one. Both training systems had features that were peculiar to the Japanese, the chief one being an insistence on jumping from low altitudes. The first jumps were made from 1,000ft, but each successive one was from a lower height, until with the sixth and final qualification jump the man was dropped from 350ft – or so the training schedule demanded. This is frighteningly low, though the German RZ parachute would open quite satisfactorily in such a short time. However there is some evidence to show that on exercises in China in 1940 and early 1941 the casualty rate from landing and parachutes that failed to open caused alarm. This could easily have come about from the parachutists being deliberately dropped too low for the canopy to function properly and for the man to have had time to get over the shock of jumping and prepare himself for landing. Whatever the original aims of the training jumps had been, it seems definite that all the Japanese operational jumps were carried out from a height of at least 800ft, and usually more.

Another feature, and one to be applauded, was an insistence on mass jumping and rallying. The mass jumps tended to become rather academic exercises in getting men through the door in the shortest possible time, and again this can be a prime source of accidents, but the intention was the perfectly correct one of getting the jumpers on to the smallest possible drop zone without scattering. Drop zones in the Pacific were never luxuriously large. The rallying methods were crude in the extreme and largely relied on some sort of noise such as a bell, but it showed that the Japanese appreciated the need to get parachutists into formed groups immediately after landing and on those occasions when they were properly dropped by their planes they cleared away from their drop zones commendably quickly. The great weakness of most of the operations was the lack of suitable aircraft and the fact that the men were often dropped from the wrong height, at the wrong speed and in the wrong place. It takes a great deal of training and initiative to overcome a start as poor as that.

The men were all volunteers at first, and all had at least two years’ service before transferring to airborne units. Later on, in the last months of 1941, it seems to have been common to draft men into parachute units without consulting them first. Whether this affected the performance of those units is not clear, though one imagines that it must have done; but there was always a section of the Japanese High Command which maintained that it was not necessary to train men specially for parachuting, and that there was no basic difference between airborne and any other type of operations. No doubt this attitude was responsible for the compulsory posting of recruits.

The army parachute units were part of the Army Air Force, possibly a German idea, and were known as raiding units. At first they were independent units, mostly organized under a central command, but by 1944 they were brought into a proper system of formation. The largest of these was the Raiding Group which had an establishment of 5,575 all ranks and was commanded by a major-general. In the group was a Raiding Flying Brigade which contained the transport aircraft, a Raiding Brigade in which were two battalions, two glider battalions and a machine gun company, an engineer company and a signal unit. Although the intention was to have more than one raiding group, in fact only the 1st was ever fully operational and was held in reserve in Japan for much of the war. A second raiding brigade was formed and put under the direct control of one of the air armies, and this brigade supplied troops for the small operations in China. A brigade consisted of 1,475 men and was tailored to the strength of the Flying Raiding Brigade which could transport it. The raiding regiment was in fact a battalion of 700 men, all parachutists and intended to be transported by a regiment of the flying brigade.

The raiding regiment was organized on very similar lines to a slimmed down infantry battalion with three infantry companies and a heavy weapons company. The major difference was that the weapons were all man-portable and the machine guns and mortars had to be carried in under-wing bundles. The individual soldier carried his personal equipment and weapons in a chest-pack which meant that he could bring himself into action on the drop zone with minimum delay, but if the containers were dropped wide he lost his spare ammunition and support weapons. Other methods of carrying equipment were tried, including one in which the chest-pack was replaced by a reserve parachute and weapons and ammunition were carried in pockets and satchels slung on either side and down the side of each leg. The raiding force that attacked the airfields on Leyte used this latter arrangement, apparently without much trouble. The great weakness of all the Japanese raiding units was the serious lack of support weapons and the inability of the unit to fight for longer than a day or two without relief. In practice they were well named as raiding units, their whole organization and equipment fitting them only for quick surprise attacks.

The Raiding Flying Regiment was intended solely to carry the parachute troops. It had three squadrons with a total of 35 aircraft, and since these were rarely the same type the carrying capacity varied but it was never adequate for the strength of the regiment it had to lift, so that the theoretical advantages of having a specialist transport force were to some extent lost. However, the idea was entirely correct, and the Japanese were far-sighted in insisting right from the inception of their airborne forces that the fighting units should be under the same command as the transport force. Quite naturally, this transport force was also used for other purposes and one of the weakening factors in the later use of Japanese parachute troops was that the raiding flying regiments had been thinned out and the squadrons reorganized as a result of the losses from US fighters and anti-aircraft fire while carrying out resupply missions.

The glider units were never fully activated although it was planned to have two regiments of 880 men in each raiding group. The reason was that Japan never got large quantities of gliders into production until almost the end of the war, when it was all too late. There had been several good designs in 1941, but it took until 1944 to build them and in the end the only use made of gliders was when a few were flown in to Luzon in 1945 carrying reinforcements. So the entire airborne force throughout the war was parachute delivered, with very few examples of deliberate air-landings as part of the air assault.

The naval parachute units were very similar to those of the army and were again a lightly equipped raiding force designed to assist the seaborne landings by dropping inland of the beaches. In October 1941 there were two such units, 1st and 3rd Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Forces. Each had a strength of 844 men, but was apparently intended to be used for certain guard duties or some similar security function. If so it seems an odd use of highly trained men, and there are no actual recorded cases of their being so employed. The 1st Special Landing Force was the parachute unit that took Menado airfield in the Celebes where it showed itself to be well trained and determined; however after that it returned to Japan and was next identified in action on Saipan where it was in an infantry role defending the island, and where it was virtually wiped out.

Considerable variety was shown in the uniforms of the wartime Japanese parachutists, though by 1944 there was little difference between ordinary infantry and parachutists. In 1940 and 1941 much of the German equipment had been copied and there was a special jump smock very like the 1941 pattern German variety. Some men wore flying suits, and the naval force was fitted out with a two-piece overall in dark green cotton-silk mixture. For winter wear there was a thick overall with a fur collar, but none of these elaborate clothes could survive for long in wartime Japan, and with the increase in the size of the airborne force the distinctive dress was severely pruned down. There were some interesting attempts to settle on a suitable headgear for jumping, and the types ranged from an adaptation of the then current tank crewman’s padded helmet to a specific parachuting helmet derived from the naval helmet. This helmet was virtually rimless, with an ordinary chin-strap and a thin liner. It was frequently worn with a cloth camouflage cover which also had a chin-strap and gave the impression of being a completely different design altogether. However, the force that landed on Leyte was virtually indistinguishable from standard infantrymen in all respects except the carriage of equipment, and it is plain that after the initial experiments the Japanese High Command was not prepared to spend time and money on special clothing and equipment for its little-used parachutists.

1. 28 November 1941. Men of the 3rd Battalion, 9th US Infantry Division unloading a 37mm gun from a DC-3. This was a very early exercise in the use of airportable troops, and it was an assault landing on Maxton Airport N.C. (US Army)

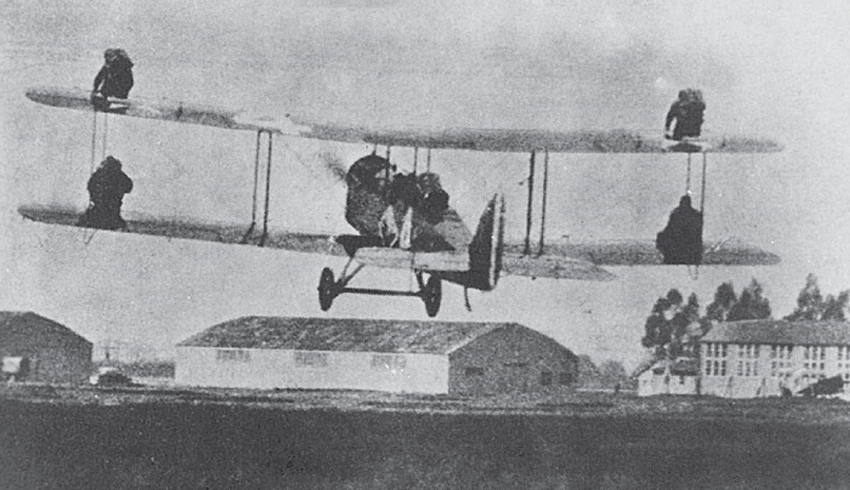

2. US experiments in the mid 1920s. A Curtiss JN-4 taking off with five parachutists, four clinging to the wings and one in the rear cockpit. (US Army)

3. Parachutists and infantry photographed at Waalhaven, 10 or 11 May 1940. The infantry are probably from the 22nd Luftlande Division who were flown in after the parachutists captured the airfield. (IWM, London)

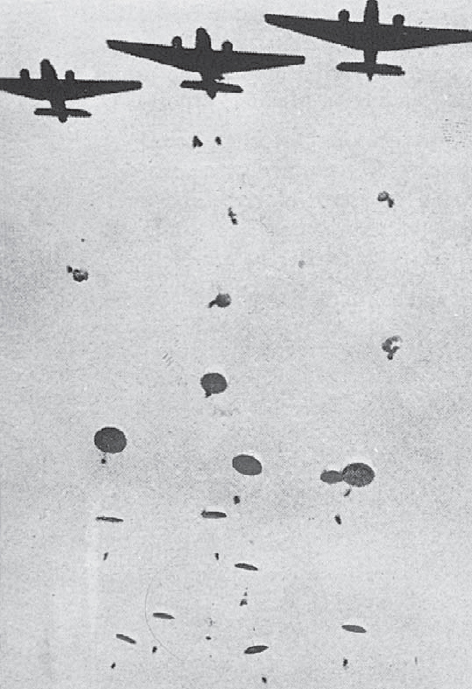

4. The parachute drop on the Corinth Canal. This in-action photograph shows a close formation of Junkers over the drop zone.

5. After the drop at Corinth there was a short pause in battle; time for a smoke, a drink, and a quick look at the map. (BArch, Bild 146-1977-163-04A / Unknown)

6. Training for the Sicily landings, 1943. Gunners of the 1st Airborne Division are pictured here firing the US 75mm pack-howitzer which was the standard gun of allied airborne forces throughout the war.

7. Battle equipment, 1944 style. Four men of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion swinging down a road in Southern France after Operation Dragoon, 15 August 1944. Notice how much each man carries, and the knives on the shin. Field dressings were carried on the helmet in Northern France, not on the foot, and all helmets had camouflage. (US Army)

8. August or September 1940. A posed photograph by men of the test platoon in a civilian DC-3 airliner. The seats have been folded back and a wire strong-point run above the door. The parachutes are probably borrowed from fire-fighting “smoke-jumpers” and the helmets might be too. The reserve parachute is very loose and would be awkward. (US Army)

9. Bringing in a resupply drop, Burma 1943/44. (John Topham Picture Library)

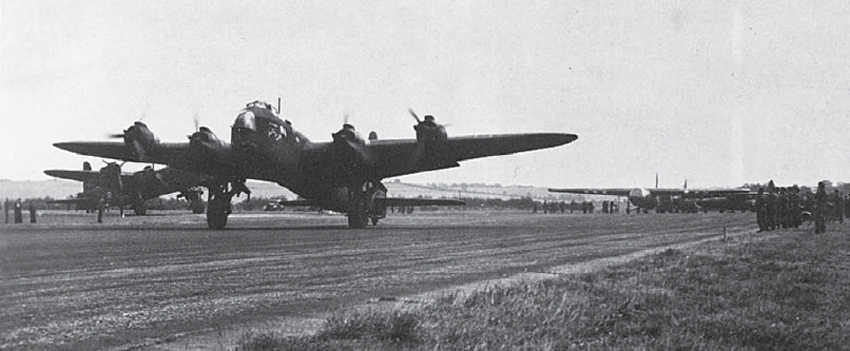

10. Operation Overlord. Short Stirling and Horsa lined up for the take off. (IWM CH 13875, London)

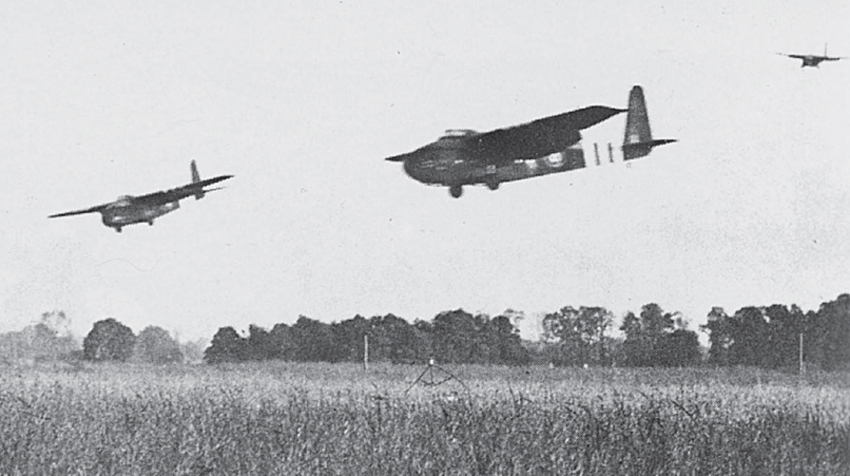

11. Hamilcars coming in to land in the 6th Division area. The enormous flaps show up very clearly. (IWM B 5198, London)

12. D-Day. Pegasus Bridge, over the Orne canal, a few days after the assault. The gliders of the coup-de-main party are clearly visible. (IWM B 5288, London)

13. 30 December 1944. A crashed C-47 shot down while dropping supplies to the besieged 101st Airborne in Bastogne. (US Army)

14. One of the first parachute exercises, late 1940. Here the paratroopers are photographed unloading a container. (IWM, London)

15. Arnhem; a position on the edge of a wood. (IWM, London)

16. The discomfort of war. A group of the 2nd Parachute Regiment having an early morning shave on a Tunisian hillside. December 1942. (IWM, London)

17. Rhine crossing, 1945. Pulling a 20mm antiaircraft gun away from a wrecked Horsa. This picture brings out vividly the dangers which faced the pilot and co-pilot in any crash landing. (IWM BU 2283, London)

18. A typical paratrooper machine gun post. This could be anywhere in Indo China, and could be any time during the French occupation. The man with binoculars is wearing canvas jungle boots, which were not normal issue during the Indo-China War, and the man well down in the pit is carrying a packet of cigarettes in the strap of his helmet. The weapons are a mixture of French and American. (EC et PA)

19. Korea, November 1957. A C-54 Globemaster is photographed being refuelled while a C-119 Fair-child Packet flies overhead. This machine had become the standard parachuting aeroplane of the US forces by the time of the Korean War. (US Air Force)

20. Suez, the heavy drop comes in while the men of the first drop hurry off the drop zone. As was the normal French practice, some loads were dropped on a cluster of time-expired man-carrying parachutes, and others were dropped on a few large canopies. The rate of descent was the same, and the cost of the smaller canopies was much less as they had already had a useful life, but the complications of the multiple opening were greater. In this picture however there have been no failures and all the loads are coming down well. They appear to be jeeps. The small canopies are the extractor parachutes which have pulled the main chutes out of their containers. (EC et PA)

21. An AH-IG Cobra gunship lifts off at the start of a fire mission. Under the starboard weapon rack is a cluster of 2.75 in rockets and a 7.62mm mini-gun, and in the chin turret is a 40mm automatic grenade launcher. (US Army)

22. 25th Infantry Division helicopter landing reinforcements in Operation Wa-hiawa, Vietnam 1966. Just visible in the after part of the cabin is the machine-gunner who provides local protection for the machine both in flight and on the ground. (US Army)

23. An OH-6A light observation helicopter from the 101st Airborne Division lands on a temporary pad at Fire Base “Victory,” 16 October 1969. (USAAF)

24. Republic of Vietnam. UH-ID helicopters of the 1st Battalion, Cavalry Regiment, 1st Air Cavalry Division (Air Mobile) come in for a landing during an assault mission 20km east of An Khe on 28 December 1965. (USAAF)