THE SECOND STRATEGY. What if one were to completely ignore narrative demands’ synergies between the social arrangements and meta-story? We occupy a certain position in the Western modern so the meta-story and all ancillary stories must be in synergy; and these ancillary stories are also produced by Black people. There is then the difficult work of narrativizing the life of Black people, as that life sits at a cardinal coordinate of capital and white power, is located in the racist schema that capital and white power describe. The task of the writer, whether of fiction or non-fiction, or of casual or bureaucratic texts, is to narrate our own consciousnesses, to describe a Black life in the register of the social and the political and not in the register of pathologies or the pathological. I am thinking here of Saidiya Hartman’s majestic book, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval, in which she refuses the forms of bureaucratic writing—state writing—that narrativize Black people into multiple forms and states of incarceration.

Gwendolyn Brooks’s Maud Martha is one such example in fiction—a narrative attending to its own expression, attending to describing its consciousness. Here in Maud Martha is a consciousness unimpeded by the demand to locate itself as adjacent to a spectator who wishes to dislocate that consciousness or make it inanimate and tangential. The mindbox opens in the reader. Brooks arranges an ordinary life without a spectator who is invested in violence as the only mode of, or code for, referencing that life:

Up the street, mixed in the wind, blew the children, and turned the corner onto the brownish red brick school court. It was wonderful. Bits of pink of blue, white yellow, green, purple, brown, black, carried by jerky little stems of brown or yellow or brown-black, blew by the unhandsome gray and decay of the double-apartment buildings, past the little plots of dirt and scanty grass…There were lives in the buildings. Past the tiny lives the children blew.28

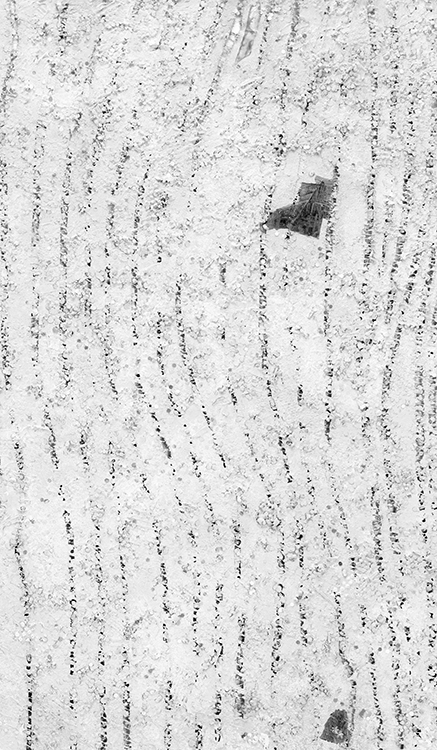

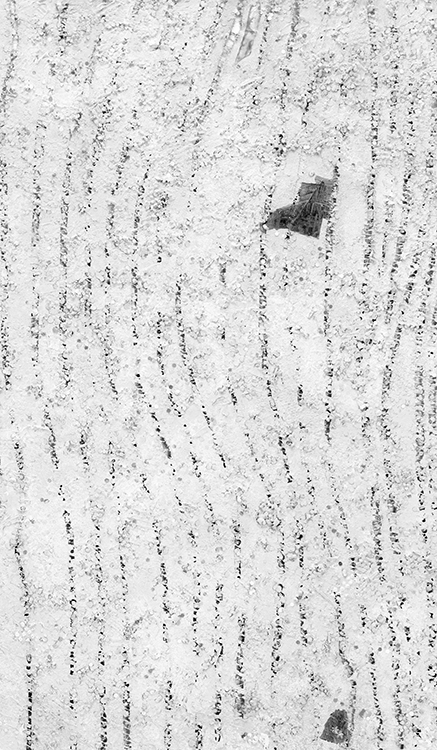

The children in her description may be very similar to the four children of the photograph at Mr. Wong’s studio. Their disarray as yet unattended by the violence of colonial pedagogy. Violence surely hovers and presages their presence, but the alertness of their presence and their desires are the foregrounded, crucial details. Brooks’s narrator sees them. There is a sense in which the children in Mr. Wong’s photograph escape the reference of colony—they have yet to be collected. It is recorded in their discombobulation, their fear, their panic, their crying, their distance—signs of their sovereignty—their resistance to being gathered.

The beauty of Maud Martha is that it assumes this sovereign point of view, and it is in this address that it locates its protagonist and the world. Maud Martha’s ruminations, too, occupy the central philosophical ground, not the partial or adjunct. Brooks writes:

People have to choose something decently constant to depend on, thought Maud Martha. People must have something to lean on. But the love of a single person was not enough. Not only was personal love itself, however good, a thing that varied from week to week, from second to second, but the parties to it were likely, for example, to die, any minute, or otherwise be parted, or destroyed…Could be nature, which had a seed, or root, or an element (what do you want to call it) of constancy, under all that system of change. Of course, to say “system” at all implied arrangement, and therefore some order of constancy.29

Brooks suggests another we entirely, one that beckons a reader, such as me, with familiarity; with a proposition; an invitation to construct the narrative’s coherence without requiring the presumption of an abject location. It is a we into which this reader might be gathered.

Palace of the Peacock by Wilson Harris is another narrative that requires no callus to withstand or elide the violence of one’s absent presence. For me, it is an origin novel in terms of its subject as well as its method. It practises what Édouard Glissant calls opacity (as does Brooks’s Maud Martha, come to think of it). The event is the event of the colonial, but all elements, all characters, are present and in flux.

In Palace of the Peacock, the I narrator—who is singular, dual, and multiple—writes:

“In fact I belong already. […] Is it a mystery of language and address?” […] I searched for words with a sudden terrible rage at the difficulty I experienced… “it’s an inapprehension of substance,” I blurted out, “an actual fear…fear of life…fear of the substance of life, fear of the substance of the folk, a cannibal blind fear in oneself. Put it how you like,” I cried, “it’s fear of acknowledging the true substance of life. […] And somebody,” I declared, “must demonstrate the unity of being, and show…” I had grown violent and emphatic… “that fear is nothing but a dream and an appearance…even death…” I stopped abruptly.30

The tale is of a journey into the forests of Guyana with all the pre- and post-Columbian actors. In the structure of the novel, you are never fully aware of its purpose or assured of its outcome. It is a reckoning with coloniality. And since coloniality seeks to order its human objects particular ways, including through narration and narrative style, then Harris’s novel refuses that narration, and narrative style, for the more complex one that exists. He uses a multifocal lens, multiple and shifting points of view—as if attempting to make the reader see, hear, everyone at once and to read everything at once. Kenneth Ramchand points out that Harris disliked “the novel of persuasion” and felt that “since the ‘medium’ has been conditioned by previous use and framed by ruling ideologies, there has to be an assault upon the medium including not only the form of the novel but also the premises about language that are inscribed in the novel.”31

At Atocha Train Station in Madrid one summer, every move my companion and I make in the line to the ticket counter is interrupted by whites wishing to cross to the other side of the room. No matter how the line moves, how much closer to the wicket we advance, we are located and used, by whites crossing the room, as the sign for space.

In Caribbean Discourse, Édouard Glissant writes about the importance of form when thinking about the ghosts of colonialism, which reverberates into the present and future. For him, narrative “implode[s] in us in clumps” and we are “transported [to] fields of oblivion where we must, with difficulty and pain, put it all back together.”32

If structures of sociality derived from the colonial moment pursue us and are anathema to our living, and if such structures include narration and narrative style, then a rethinking of these forms of address is necessary—I would say urgent, as urgent as the overturning of that sociality.