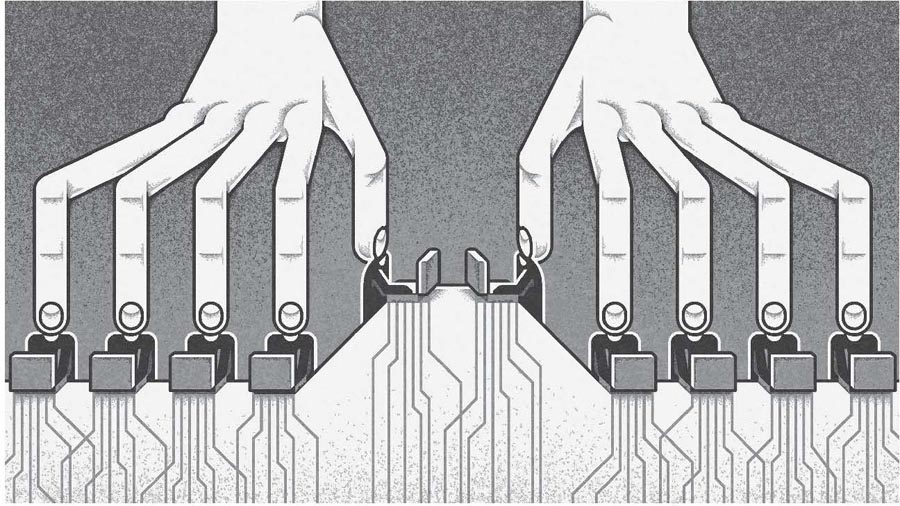

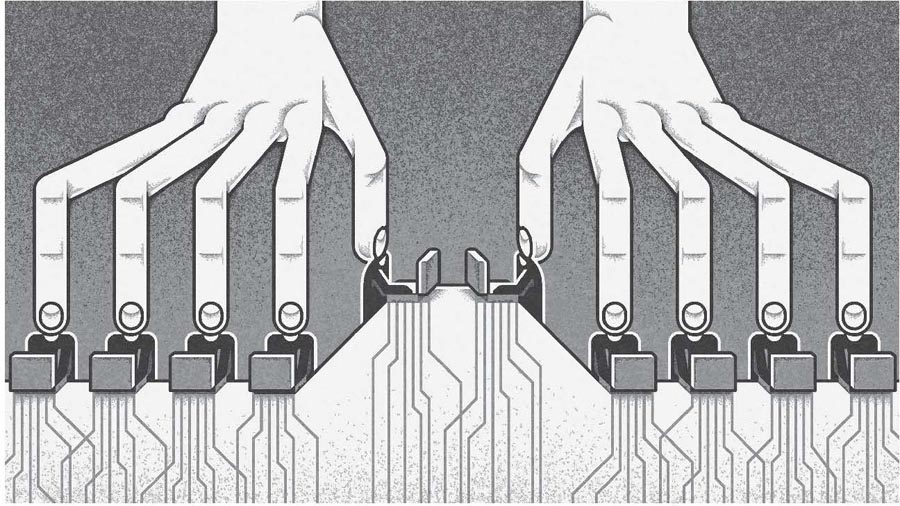

Surveillance capitalism in action: the graphic used to promote the Guardian event with Christopher Wylie and Carole Cadwalladr on 17 April 2018.

In 2018, at the age of thirty-nine, I went back to university. Ray, who I had found online, helped me load a suitcase and a few boxes of books into the back of his van, and drove me from London to Cambridge. September is a busy time in the student removals business, and on the journey we chatted about other moves he was doing that week – to Southampton, to Manchester, to Cambridge again. I noticed from his key ring that he liked German shepherds, so I asked him about them. He had two, Lola and Charlie. Both were rescue dogs: Lola was five, and just as affectionate as when she was a puppy; Charlie was older and more wary, especially around strangers. We talked about the huge difference that dogs can make to people’s physical and emotional wellbeing. When Ray asked me what I was going to study in Cambridge, I told him I was going to do politics. He thought for a moment before responding – I imagine about Brexit, Donald Trump, or both. ‘You certainly picked an interesting time to do that,’ he said.

Not everyone was as phlegmatic about my decision as Ray. For the previous six years, I had been chief marketing officer at Bought By Many, one of the fastest-growing tech companies in the UK. After handing my notice in, I posted my news on LinkedIn, and an old colleague got in touch to ask if I fancied a coffee. I said yes, assuming he was interested in hearing about my academic research, and we agreed to meet in a hipsterish café in Clerkenwell. ‘Well,’ he said, after our flat whites had arrived, ‘you’ve gone from the sublime to the ridiculous.’ He assumed I was having a midlife crisis. Alone in Cambridge, wiping down the drawers in the basement kitchen of my student flat, I could see where he was coming from.

Why had I taken this apparently baffling career path? The roots of my decision are in a Guardian live event on the evening of 17 April 2018. Everything was going well in my life at that time, but the outside world seemed to be falling apart. Things had recently gone from bad to worse for liberal democracy, with right-wing populists winning votes and parliamentary seats in France, the Netherlands, Germany and Austria. But something had also changed. The world had finally found someone, or something, to blame for Brexit, Trump and everything else: Facebook. The crisis of liberal democracy was Mark Zuckerberg’s fault.

The Guardian event was a conversation between the Cambridge Analytica whistleblower Christopher Wylie and Carole Cadwalladr, the Observer reporter who had broken the scandal. I was there with my friend Jim, who I had known since he had hired me to work at the data company Experian in 2008. We had worked together on a strategy to develop Experian’s software and data products for digital marketers, which included the acquisition of Techlightenment, a start-up with a platform for running large-scale Facebook ad campaigns. Jim had since gone on to run the marketing business of VisualDNA, a company that used personality quizzes to tailor online ads, while I had signed up hundreds of thousands of new customers for Bought By Many, mainly by targeting people with Facebook ads based on the breeds of dogs and cats the data suggested they liked. As I sat in the dark auditorium, listening to Wylie describe how Cambridge Analytica had exploited Facebook data to wage psychological warfare on ordinary people on behalf of its political clients, something began to dawn on me. I glanced at Jim and could tell he was forming the same troubling thought. Was it also our fault? Were we the bad guys? I had a horrible sinking feeling.

But then I realised that I was losing touch with reality. There was no doubt that Wylie was engaging, charismatic and witty. In his ripped jeans and big glasses, with his nose piercing and hot pink hair, he fitted the archetypal image of the data geek. It was easy to see why Cadwalladr, a feature writer, had found him such a compelling source – and why he was able to command the audience’s attention. He was an excellent storyteller, with a gift for articulating the complex technicalities of data analytics in terms they could understand. But I knew from my own professional experience that much of what he was saying about Facebook and the capabilities of targeted digital advertising was misleading. Worse, some of it was plain wrong.

As we were leaving the event, we bumped into a friend who used to run a healthcare think tank, there with her husband. They were distressed and angry about what they had heard. Though they are active members of the Green Party, this wasn’t about party politics; it was about the integrity of democratic institutions. Facebook was undermining the basic foundations of democracy, and something had to be done. I share their concerns about contemporary politics, but I did not agree that bringing down Facebook was the answer. I wanted to explain what was wrong about the story Wylie had told, and why it was dangerous that so many intelligent and thoughtful people were being taken in by it. After all, I’d worked in data analytics and digital marketing for eighteen years and had nearly been taken in by it myself.

Despite wanting to, I didn’t say anything – I realised that I didn’t have the right vocabulary. At that time I spoke the arcane, technocratic language of the data-driven marketer. I could have talked about segmentation, prospecting, cookies and lookalike audiences, but that wouldn’t have helped. I needed a new way of communicating about data, so I quit my job and went back to university to learn it.

* * *

In a relatively short time, a highly influential theory has been developed to explain the apparent connection between technology companies like Facebook and the political and social convulsions of the last few years. It focuses on the role of data, and it’s called ‘surveillance capitalism’. The term was coined by the Harvard Business School professor Shoshana Zuboff in 2015, but it was the recent publication of her 700-page book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism that propelled it into the mainstream. Many other high-profile scholars with critical perspectives on technology, including Zeynep Tufekci, Siva Vaidhyanathan and John Naughton, also subscribe to it. This is the case it makes against Facebook.

When you sign up for Facebook, Instagram or WhatsApp, you give Facebook some of your personal data, in order that you can construct a profile and find other users. This might include your phone number, your date of birth, what school you went to, your favourite music and so on. As you continue to use Facebook, this is supplemented with other data, such as the friends you connect with, the groups you join and the organisations and public figures you follow. We’ll call this kind of data profile data. Facebook also collects data about your activity – for example, which news stories you like or share, which videos you unmute and which of your friends you interact with most frequently. Because it is integrated with other websites through features like ‘Login with Facebook’, it’s also able to collect data about your browsing elsewhere on the web. We’ll call this second kind of data behavioural data.

Your profile data and your behavioural data are then combined by Facebook in a way that means you can be put into a near-infinite number of possible audiences, which advertisers can then pay to target using Facebook’s tools. For instance, a mattress company might want to promote its new product to women aged between twenty-nine and forty-five who like yoga. Data on Facebook enables that to happen. If you fit that profile, an ad with, say, a woman floating above a mattress in the lotus position will appear in your feed. If you don’t, it won’t. If the mattress company was advertising in traditional media, it would have to make do with placing its ads in magazines aimed at health-conscious women, or on billboards in the train stations of major cities. With these approximations, most of the people who saw the advert wouldn’t be the target audience.

Collecting and compiling data in this way helps make Facebook’s advertising space more valuable than most advertising space in magazines and billboards. It’s an important part of how Facebook makes money. The theory of surveillance capitalism calls this business model ‘fundamentally illegitimate’. That’s a pretty strong claim. If something is illegitimate, we must not stand for it – it means it is not only unjust, but actually intolerable. A classic example of illegitimacy might be an armed group seizing control of a democratic state through a coup. There are three reasons why surveillance capitalism theory says Facebook’s use of data is just as grave.

Firstly, you didn’t give Facebook your permission to use your profile data in this way. You didn’t consent to it. Facebook’s terms of service or its data use policy might talk about it, but these documents are long and impenetrable. It isn’t fair to expect that people actually read them, so any consent implied by your acceptance of them can’t be regarded as informed consent.

Secondly, the collection of behavioural data is both intrusive and essentially covert – in other words, it amounts to surveillance. As such, it’s a violation of privacy rights that is equivalent to someone secretly filming you in your house or wiretapping your phone. Again, whatever it says in Facebook’s terms and conditions is irrelevant, because understanding the technical processes they describe is beyond the capability of most Facebook users. Furthermore, it is practically impossible to opt out of your profile and behavioural data being used without losing access to the services Facebook provides.

Thirdly, the social relations created by Facebook’s business model are expropriative and extractive. Profile data should be seen as your digital property, and behavioural data as the surplus from your digital labour. Facebook takes these from you, making you the modern-day digital equivalent of a serf toiling to enrich a cruel feudal lord. So the power that Facebook derives from data is ‘illegitimate’ because it has been gained by means that no reasonable person would agree to if they understood them.

The graphic on the website promoting the conversation between Christopher Wylie and Carole Cadwalladr is straight out of a sci-fi dystopia: two giant hands bear down on a row of people sitting at computer screens. They are literally being manipulated: the tip of each finger fuses with the head of each figure, making data pour out of their devices, as if they are having the lifeblood drained out of them. The caption reads, ‘The internet has been corrupted into a propaganda tool for the powerful,’ but it could just as well have been entitled ‘Surveillance capitalism in action.’

But that’s not all. Surveillance capitalism theory alleges that Facebook’s pursuit of growth is motivated by a desire to accumulate more of this data and that its rapid expansion into almost every country in the world is explained by its voracious quest for profit. The use of its apps to disseminate political propaganda, extremist content and fake news serves its objectives; prurience and outrage lead to more clicks and shares, and therefore to the generation of more behavioural data. The ethnic cleansing of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, the rise of alt-right conspiracy theories, the anti-vaxxer movement and the election of populists, from Donald Trump to Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines and Matteo Salvini in Italy, are among the catastrophic consequences of Facebook’s business model.

Surveillance capitalism in action: the graphic used to promote the Guardian event with Christopher Wylie and Carole Cadwalladr on 17 April 2018.

At the same time, surveillance capitalism theory claims that Facebook diminishes human freedom. The design of its user interfaces, informed by vast quantities of behavioural data, is intended to encourage you to spend more time using its apps, which has a detrimental effect on your wellbeing. The more extreme manifestations are increases in anxiety, self-harm and suicidal thoughts among young people, but they also include more generalised feelings of distraction, dissatisfaction, boredom and malaise. Facebook is using the data it has illegitimately acquired from you, along with the talents of the data scientists, software engineers and designers it employs, to create an epidemic of digital addiction. As the former Facebook employee Antonio García Martínez puts it, Facebook is ‘legalised crack on an internet scale’.

Put all that together, and this is the terrifying story. Facebook steals personal data from you and uses it to manipulate you into becoming addicted to its apps, so you produce even more data, which it also steals. Facebook then sells the data it has stolen from you to advertisers, so they can manipulate you into buying their products or voting for their side in a referendum or election. Facebook doesn’t care why its advertisers want your data, how they use it or what the consequences for society are, because all it cares about is profit – as long as your likes, shares and comments keep producing data it can sell, it’s all the same to them. Cambridge Analytica helped the Vote Leave campaign and the Trump campaign use your data as a weapon against you, and Facebook couldn’t care less.

Convinced? If you are, I completely understand why. We are at a moment of extreme pessimism about data. Every day seems to bring news stories implicating social media and mobile phones in cyberespionage, organised crime or authoritarian repression. The risks of speaking your mind online have never felt more acute, so it’s hardly surprising that encrypted private messages on platforms like WhatsApp and Snapchat are fast becoming our preferred way of communicating. Meanwhile, tech companies seem to grow ever more powerful. A decade ago, just one of the world’s largest ten corporations was a technology company; today, seven out of ten are. The market capitalisation of tech giants like Facebook, Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Apple is now bigger than the GDP of most countries – an ascendency that has made their founders and executives spectacularly wealthy. By restricting how data can be used, policymakers promise to repair the damage to world order, civility and equality that tech companies seem to have inflicted.

However, there is another, more optimistic side to the story – the story of good data. In telling it, I begin from a different position to most people writing about data and big tech. Many of the academics, cultural commentators and journalists who shape public opinion on these issues are deeply knowledgeable, but they also tend to be outside observers, who haven’t run ad campaigns on Facebook or analysed Google data to grow a business. By offering the inside perspective of someone with real-life experience of digital marketing and data science, I hope to provide new insights and ways of thinking about these important issues.

It’s a story that might seem contrarian at first. After all, it highlights the reasons not to be worried about how big tech companies are using our data. It shows that targeted digital advertising isn’t as personal, sinister or persuasive as you might think, and that most of the data we produce isn’t a precious commodity that we’re being cheated out of. It explains why the power of big tech companies, despite their scale, is not like the power of states, and it reveals how they can be reformed to better serve the public interest without banning them. But most importantly, it’s the story of the huge societal benefits that we can unlock by putting more, rather than less, data into the public domain. Governments’ data. Tech companies’ data. And our data.

* * *

Digital technology is so pervasive that almost every aspect of our daily lives generates or consumes data. It will only continue to proliferate. Whether or not this data is harnessed as a force for good depends on choices we make together about social norms, and choices about laws and regulations that politicians make on our behalf. At the moment, surveillance capitalism theory is framing those choices. But from my perspective, the risks associated with tech companies’ use of data have been dramatically exaggerated, while the benefits of data openness, both to individuals and society, are being undervalued or even forgotten. It’s time to rediscover the possibilities for data to make life better for all of us. It’s time to talk about good data.