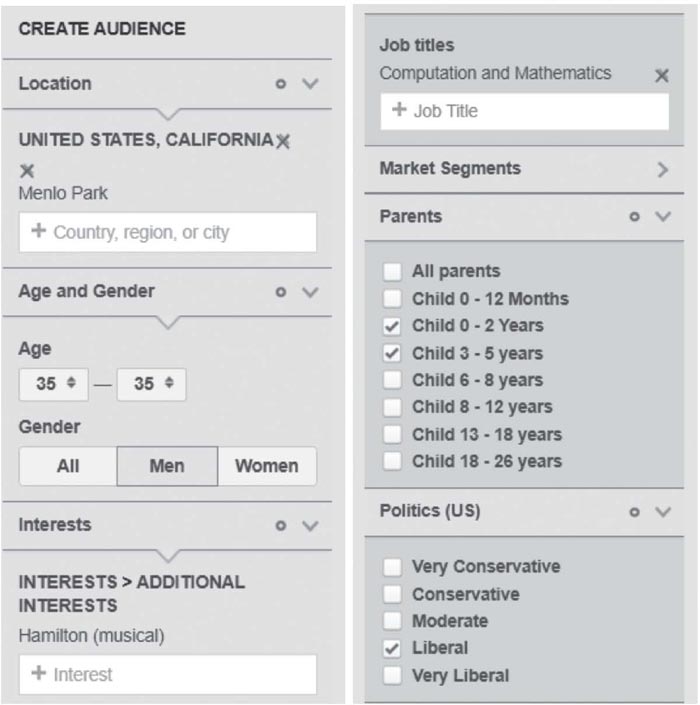

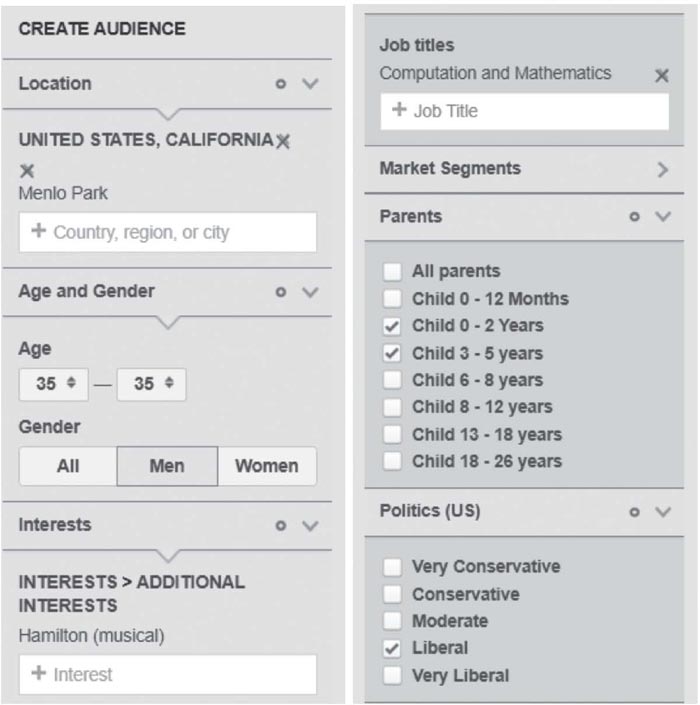

Targeting people like Mark Zuckerberg with Facebook Ads Manager.

TAKING OVER THE PANOPTICON

The time has come for us to meet Jeremy Bentham, one of the most influential philosophers of the modern era. He’s been waiting in the wings of this book – in fact, David Runciman’s metaphor of “moral fog”, which was so important in the last chapter, has its origins in Bentham’s writing. Now we can invite him to take centre stage.

Bentham lived from 1748 to 1832, through times of great political, social and technological upheaval. He was born shortly after Bonnie Prince Charlie went into exile, and shortly before the start of the Industrial Revolution. He was about twenty years younger than Adam Smith and twenty years older than Napoleon Bonaparte. The French Revolution happened in the middle of his life and the Regency happened towards the end of it.

Although he never used the term himself, Bentham is best known as the founding father of utilitarianism – the theory of ethics that says we should decide what is right based on what brings the greatest happiness to the greatest number of people. In case you think that’s not relevant to a discussion of twenty-first-century technology companies, consider this: when the German government set rules for autonomous vehicles in 2017, it insisted that their software operate on utilitarian principles. When a collision involving a self-driving car is unavoidable, the car must minimise casualties – even if that means sacrificing the lives of its own passengers.

Bentham’s commitment to utilitarian principles expressed itself in ways that show him to have been remarkably ahead of his time. He believed women were equal to men, and argued that they should be given the right to vote more than 100 years before suffrage was finally granted in 1918. And in 1785 he wrote the first documented argument in favour of decriminalising gay sex. As far as Bentham was concerned, since it harmed no one and gave pleasure, prohibiting it was simply wrong.

On the other hand, some manifestations of utilitarian thought make Bentham seem wildly eccentric. Wanting to undermine what he saw as sentimentality about the human body, he specified in his will that his corpse should be publicly dissected, then preserved and used as a decoration. As a result, you can see him on display in a glass case at University College London. Well, you can see parts of him – the mummification technique used on his head went wrong, so it was replaced with a wax version, which sports a wig made from his hair.

Bentham’s thinking about infanticide was even more challenging. Utilitarian philosophy told him that there were two reasons why murder needed to be prohibited: because it robbed people of the pleasures of being alive and because if murder was permissible, everyone would live in constant fear of being killed. It seemed to him that neither of these reasons applied to newborn babies. They were unaware of their own existence, so couldn’t be troubled if it was taken away from them; and they hadn’t yet learned to experience fear, so couldn’t be afraid of being killed. On the other hand, parents who smothered their newborn children out of desperation would suffer the terror of being put on trial and condemned to death; Bentham thought it caused pointless suffering for infanticide to be treated in the same way as murder, when social opprobrium was punishment enough.

Bentham’s eccentricity is to the fore in the Panopticon, his innovative design for a prison that profoundly shapes how we think about power in the era of big tech. From the 1970s onward, academics increasingly used it as a metaphor for state-run electronic surveillance. More recently, it has become popular as a metaphor for social media – in fact, if you search ‘panopticon’ now, alongside scholarly articles you’ll find long reads from the Guardian and TechCrunch discussing Facebook and Google. The intriguing story of how that came to pass will unfold throughout this chapter, but first we need to take a virtual tour of Bentham’s imaginary prison and see how it works.

The first thing to notice about the Panopticon is that it is circular. On each of its six floors, rows of cells run all the way around the perimeter, surrounding a cavernous atrium. In the centre of the atrium is a tower with large windows that are covered with venetian blinds: this is the inspector’s lodge. Stepping inside the lodge, it becomes clear that the windows provide a view into every cell in the prison. The higher windows are accessed via a spiral staircase, and a trapdoor enables the inspector to come and go without being seen.

The next stop on the tour is an empty cell. The partitions separating it from the adjacent cells carry on for a few feet beyond the grating, limiting our view. The only cells in our field of vision are across the atrium, far away. By contrast, the lodge, looming overhead, is impossible to ignore. However, the position of the blinds and the fact that it is dark inside the tower prevents us from seeing inside. At this very moment, the inspector might be watching us; or she might be observing a cell on the other side of the prison; or she might have slipped through the trapdoor and gone for a tea break. There is no way of telling. The genius of Bentham’s design starts to dawn on us: as the prisoners in the Panopticon know that they might be under observation by the inspector at any given moment, the rational thing for them to do is to behave at all times. In other words, the Panopticon makes them self-discipline.

The Panopticon wasn’t just a concept; it was a business plan. Bentham’s intention was to persuade the British government to pay for the construction of a Panopticon and appoint him to run it on what we would now call an ‘outsourcing contract’. He saw it reducing prison staff costs: the lodge would only need to be occupied some of the time, so he could employ fewer inspectors, while self-disciplining prisoners would need fewer guards to control them. What’s more, he could save money on shackles and chains, as even the most boisterous prisoners would quickly realise that getting up to mischief was futile. He even wondered whether it would be possible to raise extra revenue by offering tourists entry passes to the inspector’s lodge. He was a prisons entrepreneur – like an eighteenth-century version of the security companies G4S in the UK or CoreCivic in the US.

Unfortunately for Bentham, the government, though initially enthusiastic, never struck a deal with him. And while many prisons have since been built on panoptic principles, Bentham made little money from the idea. Would he have been consoled to know how frequently the Panopticon would be invoked in discussions of Google and Facebook? Or would that knowledge have had no value to him, since it would not have improved his material circumstances? To mull over that question is to use what Bentham called felicific calculus: adding up the amount of happiness caused by something and subtracting the amount of unhappiness to determine whether it’s a good thing. We touched on this idea in Chapter One when we considered the trade-offs involved in implementing legislation like GDPR which affects everyone, and it will be particularly important in this part of the book.

Is Facebook a Panopticon?

What do critics of Facebook mean when they claim that it’s a Panopticon? Most straightforwardly, it means that everything we do on Facebook is visible. It’s obvious that posting a status update or liking an article shared by a friend is visible – that’s the point of doing it. It is somewhat less obvious that the activities we might prefer to keep to ourselves – like tracking down the profile page of a new colleague or looking at an ex-partner’s photos – are also in some sense visible. They are not visible to other Facebook users, but they are logged in Facebook’s databases and visible to its algorithms, and there is a possibility that they might be looked at in encoded form by a Facebook engineer in the course of their work. Integration with other websites makes some of our online activity elsewhere on the web visible to Facebook in the same technical sense – its algorithm can ‘see’ that you browsed that mattress but never placed an order, for instance. Now, it isn’t true that everything in Facebook’s network is visible – encrypted messages on Messenger and WhatsApp can only be seen by the sender and the recipient – but if you think it’s meaningful to talk about algorithms ‘seeing’, it makes sense to talk about Facebook being panoptic, with a small “p”.

However, a Panopticon is a prison as well as an observatory. To say that Facebook is – in the words of Newsweek – an ‘online panopticon’ is to say that its users are prisoners, and that a form of authority is exerting control over them. Control in the Panopticon involves the physical constraint of cell walls, but its defining characteristic is self-discipline produced by the prisoners’ awareness of constant surveillance. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell brought this idea vividly to life through the all-seeing figure of Big Brother. Conceived in the aftermath of the Second World War, in the context of Stalin’s totalitarian rule in the Soviet Union, Orwell’s version of the Panopticon is electronic rather than architectural. A network of CCTV cameras in homes, workplaces and public spaces gives the state’s security services total visibility of its population:

There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. How often, or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was guesswork. It was even conceivable that they watched everybody all the time. But at any rate they could plug into your wire whenever they wanted to. You had to live – did live, from habit that became instinct – in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinised.

Surveillance-driven self-discipline makes dissent and resistance to the state impossible. Not even writing a journal can be concealed, never mind political organising. Although the hero of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith, can leave his flat, go to the office, visit an antique shop and take a daytrip to the countryside, he is still effectively a prisoner because he knows Big Brother is watching. Just as the inspector’s lodge in Bentham’s Panopticon did not depend on any individual inspector, Big Brother is not an individual leader or official, but rather a technological system of control.

That brings us to another hugely significant figure in the history of ideas: Michel Foucault. If Bentham appears to be an English eccentric, Foucault – shaven-headed, wearing oblong glasses and fond of a turtleneck – is the epitome of French intellectual cool. His academic influence in sociology, history, psychology, philosophy and political theory has been so great that it’s hard to exaggerate. Foucault was fascinated by power, and much of his writing tries to explain what power is and how it works. Bentham’s Panopticon resonated with him because it demonstrated how disciplinary mechanisms could be used to exercise power over a large number of people in a highly efficient manner. It seemed to Foucault that the design principles of the Panopticon were applicable not just to prisons, but to schools, factories, job centres, asylums and hospitals. If they know they might be being watched, pupils won’t copy each other’s home-work; assembly-line workers won’t attempt to form a union; patients with symptoms of a contagious disease won’t break social distancing rules. In fact, Foucault argued, if you closely examined the way any modern institution worked, you would find the same dynamics of inspection and self-discipline. And if you thought of inspection not as literally watching people but as gathering data to measure, benchmark and classify them, the model was scalable to entire national populations. We live, he wrote, in ‘the disciplinary society’.

If Facebook is a Panopticon, as many of its critics claim, its power must operate in a way that Bentham, Orwell or Foucault would recognise as disciplinary. Control must be being exerted over users in a way that undermines our freedom, putting us in the same position as prisoners, pupils, oppressed workers or patients. That control doesn’t need to be exerted by a particular individual like Mark Zuckerberg; it can be exerted by a system – an inspector’s lodge, a Big Brother or a set of algorithms. If there are personnel involved, they can change without compromising the system: inspectors can wander in and out of the lodge, and there can be turnover in the ranks of the Thought Police, or among teachers, doctors, supervisors and developers at Facebook’s Menlo Park headquarters. Facebook isn’t a state, so the objective of this control is not to maintain political order; as a multinational corporation, its objective is to maximise profits. It follows that the behaviours Facebook wants from us are the ones that drive up its revenues – spending time on Facebook-owned apps, clicking on ads and giving up data that can be used in targeting or optimisation.

It probably won’t surprise you to learn that I don’t find this presentation of Facebook as a digital Panopticon very persuasive. Firstly, power in a Panopticon is based on a massive asymmetry of knowledge. The inspectors can see everything that the prisoners do, but the prisoners can see nothing of the inspectors. However, Facebook isn’t like that at all. Anyone can go to Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook page and see that he is a fan of the musical Hamilton, or view Sheryl Sandberg’s page and see that she likes coffee, grapefruit and frozen yoghurt. Anyone can follow Facebook’s head of virtual reality, Andrew ‘Boz’ Bosworth, for the inside track on development of the new Oculus headset, or watch Instagram Stories by the division’s CEO Adam Mosseri. Of course, Facebook executives could, if they wanted to, use their internal systems to see more of us than we can see of them, but they are not concealed; if they are inspectors, their quarters have windows that the prisoners can see through.

Secondly, in a Panopticon, power only flows in one direction. The inspectors exert it over the prisoners, who must submit to it. Panoptic accounts of Facebook often associate targeted advertising with this one-sided power dynamic, as we saw earlier in the book. In this telling, the inspector’s lodge is the Ads Manager software, built and maintained by Facebook, but occupied and used primarily by its advertiser clients. Looking out of its windows, observing the characteristics and behaviour of the prisoners, inspector-advertisers can decide which groups they would like to target and place their ads on the cell walls.

The trouble with this version of the Panopticon story is that it assumes an essential difference between a Facebook advertiser and a Facebook user. But this difference doesn’t exist: you have to be a Facebook user to advertise, and Facebook’s advertising tools are accessible to all 2.5 billion users. Running an ad campaign on Facebook doesn’t require any special skills; the tools are remarkably easy for anyone to use. Let’s look at what would be involved in targeting Mark Zuckerberg with a Facebook ad. While it isn’t technically possible to target individuals or groups of fewer than 100 people, we can use publicly available information about Zuckerberg to build a campaign that we could expect to reach him. As you can see from the below screenshots from Ads Manager, it is easy to target an advert at men aged thirty-five who are located in Menlo Park, hold liberal political views, have children under the age of five, work in computation and mathematics, and like the musical Hamilton. All you’d need to do it right now is a credit card and a budget of at least $1.

Jeremy Bentham would not think much of a Panopticon in which prisoners were allowed to be inspectors and where every prisoner had access to the inspector’s lodge – he might think it was rather missing the point. Similarly, it would have detracted from the nightmarish vision depicted in Nineteen Eighty-Four if the proles had been able to plug in to the wires of the ruling elite at will. For Foucault, meanwhile, one of the reasons the Panopticon makes it possible ‘to perfect the exercise of power’ is because it ‘reduce[s] the number of those who exercise it’. By contrast, Facebook has increased the number of people exercising power: there are now more than seven million Facebook advertisers. Power can’t be flowing only in one direction when there are seven million inspectors moving between the lodge and their cells.

Targeting people like Mark Zuckerberg with Facebook Ads Manager.

The accessibility and widespread usage of Facebook ads is not the only evidence that power is flowing in multiple directions. A Panopticon is supposed to make organised resistance impossible, but we saw in the last chapter that Facebook features can be used by the weak against the powerful – in Evan Mawarire’s #ThisFlag protest against the repressive government of Zimbabwe, for example. There have even been occasions when these features have been turned against Facebook itself. In 2007, the company rolled out a programme called ‘Beacon’ that automatically posted Facebook stories about users’ purchases on participating third-party websites. There was nothing technologically remarkable about it, but what was significant was the co-ordinated resistance that was mobilised against it – on Facebook. Objecting to Beacon on privacy grounds, the advocacy organisation MoveOn petitioned Facebook to withdraw it, using a Facebook group. In a matter of days, the group attracted tens of thousands of members, and a class action lawsuit against Facebook followed. Mark Zuckerberg admitted that Facebook had made a mistake, and Beacon was shut down in 2009.

The final reason I don’t think Facebook is a Panopticon is that characterising the way we behave on social media as ‘self-disciplining’ seems at odds with practical experience. Think about the time you spend on Facebook or Instagram. Are you constantly aware that you might be being observed by someone much more powerful than you? Do you scroll through your feed or react to a news story shared by a bad-tempered uncle because it’s what Facebook expects of you? Do you modify your behaviour to align with what Facebook wants, to avoid punishment? Me neither. Scholars who think we live our digital lives inside a Panopticon might say that we’re in a state of false consciousness, meaning that we’ve internalised the system of control to such an extent that we are no longer aware of our real motivations. Whether or not you’re persuaded by this claim will depend on how well you think you know your own mind, and how capable you think you are of making your own choices, a question we will return to shortly.

If you want to see self-discipline in action, think about your experience of living under lockdown during the Covid-19 pandemic. In the UK, the government stipulated that we could only leave our home to buy food, collect medicine or exercise. The chief enforcer of this mass house arrest was not the police, but the general public. Some people reported their neighbours to the authorities for going running more than once a day, some chastised ‘non-essential’ businesses like ice cream vans for continuing to trade and others photographed people sitting too close together in public parks. It marked a resurgence of an old form of peer-to-peer surveillance, often associated with the Stasi’s network of informers in East Germany during the Cold War, but traced as far back as Calvinist communities in sixteenth-century Holland by the sociologist Philip Gorski. Its effect is that people regulate their own behaviour, weighing up how their actions will be judged by observers so they can avoid provoking disapproval and risking punishment.

Is the Panopticon more effective as a metaphor for Google? It’s obvious that much of our online activity is technically visible to Google – not just because Google Search, Gmail, YouTube and other Google products are so embedded in our everyday lives, but because its technology is used to trade the advertising space on more than two million websites through its ‘partner network’, and to measure traffic on another 30 million websites through Google Analytics. However, as we’ve seen, in addition to visibility, there needs to be knowledge asymmetry, power needs to flow in one direction only and we need to be able to describe Google’s users as self-disciplining.

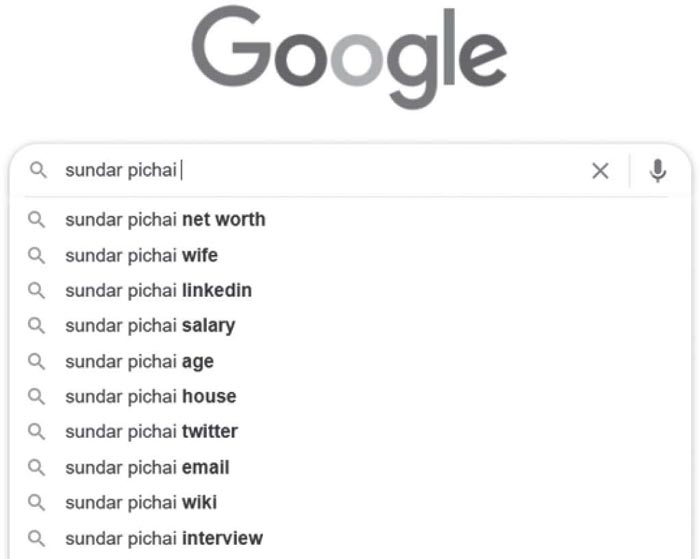

As with Facebook, Google executives can see things about us that we can’t see about them if they access our Google histories. But they themselves aren’t hidden – in fact, exposing information about public figures is a function of Google Search. That it reveals more about Google’s CEO than about you or me some-what redresses the power imbalance – see what Google suggests if you type ‘Sundar Pichai’ into the search box (opposite).

At the same time, power on Google platforms clearly flows in many different directions. It’s harder and more expensive to set up and run campaigns on Google than on Facebook, but there are still four million Google Ads advertisers. Of the 31 million people who have their own YouTube channel, around 16,000 have more than a million subscribers each, double the circulation of the New York Times. Finally, self-discipline is an overcomplicated way of explaining why Google’s services are so widely used – that they are incredibly effective and mostly free seem like more straightforward reasons.

How Google Search makes Google CEO Sundar Pichai visible.

To sum up, the power relations of Facebook, Google and other tech platforms are not like those of the Panopticon. But if the Panopticon is the wrong model for how we should think about power in the era of big tech, what is the right one?

Cambridge Power

Foucault explored a different type of power in the last ten years of his life, after he had written about the Panopticon in Discipline and Punish. In academic literature, this type of power is generally referred to as ‘structural’ or ‘constitutive power’, but I’ve never found those words very intuitive. So I will call it ‘Cambridge power’, and use a story from Cambridge to bring it to life.

The story begins on a bright, cold day in November 2018, in the History Faculty Building. I was standing in a basement corridor outside a classroom, waiting for a lecture to begin. I had spent a fruitless hour in the library, unable to concentrate on reading because of a draught on the back of my neck that seemed to pursue me wherever I chose to sit. Designed by James Stirling, after whom the RIBA Stirling Prize is named, the History Faculty Building is a Grade I-listed classic of modern architecture, so I couldn’t understand why it was always so uncomfortable. On my phone I found an Architectural Review essay about it from 1968, which explained that the controls for heating and ventilation were complicated to operate. The author predicted that they were likely to get ‘fouled up through mismanagement’ as ‘most of the occupants of the building will be humanities-oriented, and therefore likely to fall below the national average in mechanical literacy and competence’. In other words, if I was cold, it was my own fault.

Before arriving in Cambridge I’d looked through the lists of lectures for the term and noted down the ones I wanted to go to – either because they were relevant to the politics course I was taking or because I thought they would enrich my understanding of the world. I had imagined feasting on ideas from history, sociology, philosophy and English literature, and even contemplated signing up to learn modern Greek. However, five weeks into my life as a mature student, I had already given up on that project. The required readings for my course – journal articles, chapters or even the entirety of academic books – averaged over 500 pages a week. On top of that were three two-hour seminars and a mandatory class on social science research methods at 9 a.m. on a Monday morning. Finally, I was supposed to be making progress with my research thesis, as my supervisor would soon be uploading a progress report about it to the student administration system. Another habit I had imagined before moving to Cambridge was going for a long run by the river every morning. In practice, I was managing a short loop of Midsummer Common and Jesus Green two or three times a week – a joyless hurrying before the day’s labour began. More keenly than at any point in my career, I felt like there was no time to do anything apart from work.

The lecture that day was the first in a series about our friends Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, who we will meet in the next chapter. It was aimed at second year undergraduates, meaning that I was waiting in the corridor with students roughly half my age. Some wore college boat club hoodies and tracksuit bottoms; others had bleached hair and turned up jeans. Some were skittish; others subdued. When the hour came round, the door to the lecture room opened and there was a sudden melee. Trooping in, I was vividly reminded of being at school: long rows of wooden desks and stackable polypropylene chairs faced a whiteboard; I could smell the inside of my old pencil case – HB pencil shavings, blotting paper suffused by blue-black Parker ink. I went to the back corner of the room – ostensibly to be close to a socket where I could plug my laptop in, but really because I felt like an outsider who should be kept apart from the other students. A young man sitting on the row in front warily passed me a photocopied handout. Striking up a conversation seemed impossible; basic social skills had deserted me.

Eventually the lecture began and I quickly became absorbed in stories of Bentham’s life. It was only when the lecturer started outlining the themes of the following week’s lecture that I realised an hour had passed, remembering with a jolt that I was due in a seminar on comparative politics and religion five minutes later. I packed away my things and hurried out of the building and across the campus.

Unlike lectures, seminars involve small groups and require active participation. On the surface they look like the sort of progress meeting you might have if you work in an office; participants generally sit around a table with a senior person chairing the discussion. But they are different in several respects. Firstly, there isn’t much chit-chat: there tend not to be ice-breakers to put people at their ease, or jokes to provide light relief from difficult conversations. Secondly, facilitation is the sole preserve of the seminar leader. If you want to say something, you put your hand up and wait until they invite you to speak. Thirdly, the default mode of a seminar is critique. Comments on the readings tend to probe their weaknesses rather than celebrate their strengths. It’s not really the done thing to offer other people encouragement or praise for what they have said: better to point out a flaw in their argument. As a result of these conventions, seminars are usually serious affairs, with a rather negative energy.

For me, participating in seminars meant switching off the instincts about how to interact in groups that I’d built up over the previous eighteen years in my professional life. Sometimes I would arrive brimming with enthusiasm about the week’s readings, only to feel my excitement ebb away as I realised the format wouldn’t allow the kind of sparky, collaborative discussions that I enjoyed so much. At other times, I would turn up feeling useless and underprepared – either I had been too lazy to read the articles and chapters closely enough, or I was too stupid to grasp them. On this occasion, I asked a question about different meanings of secularisation and made a point about the entanglement of national and religious identity. I had no idea whether the contributions I was making had any value. There was a moment of silence, and then the seminar leader addressed the room: ‘So what’s at stake here?’ What was I to make of that? Should I feel embarrassed? Ashamed? I became terrified of saying the wrong thing, getting butterflies when I even thought about raising my hand. I longed for the banal reassurances of normal working life – for someone to say something like, ‘I agree, Sam, that’s such a great point,’ or even ‘Picking up on what Sam said earlier . . . ’

It was three o’clock by the time the seminar finished and I hadn’t eaten anything since breakfast. I was too hungry to think straight. Marks and Spencer was on the way back to my flat, so I went in and bought a tub of hummus and a sliced white loaf. I took my meagre shopping back to the basement kitchen, and ate while staring into space. I had turned all the radiators up as high as they would go, but my study-bedroom refused to warm up. I made a cup of tea and settled down at my desk to spend three hours on the readings for the next seminar. It was already getting dark.

Later, I went out to the pub to meet Alex, my old colleague Helen’s brother-in-law. A philosophy professor at Boise State University in Idaho, he was in Cambridge for a year on study leave, researching a book. Both on sabbatical at the same stage of life, and with a shared love of real ale, we had quickly become friends. I had planned to ask him about Bentham and Foucault, but I realised what I really needed was to moan to someone about what a miserable time I was having. I moaned about the work-load, the seminar format and the absence of feedback. I moaned about the gulf between what I had expected my year in Cambridge to involve and the drab and gruelling reality – about the lectures I was missing, the runs I wasn’t going on, the sports teams I hadn’t joined, the cloisters I wasn’t lingering in, the candlelit choral concerts, formal dinners and wine tastings I wasn’t attending. I summed up: ‘I’m just not having the Cambridge experience.’

‘Hang on a minute.’ Alex took a sip of his beer. ‘You just told me you’ve spent most of the week cold and alone in your room, worrying that all your endeavours are worthless. That is the Cambridge experience.’

How is the rapid change in my personality during my first term at Cambridge best explained? Was it more evidence that I was having a midlife crisis, as the old colleague I mentioned at the start of this book suspected? Or did I simply ‘lose my confidence’? Alex put his finger on an alternative explanation: I was experiencing the psychological, emotional and physical effects of Cambridge power.

Cambridge power was everywhere. It had got under my skin and worked on me all the time. But it wasn’t being deliberately exerted by seminar leaders, by the university vice-chancellor or by a carefully designed system of control. It just was. It emerged mysteriously from the interaction of architecture, climate, bureaucracy, social norms, memory, pedagogical practice, commerce and who knows what else. It structured and constrained the actions I could perform, the words I could use, the choices I could make – even the possibilities I could imagine. Under its spell, I was re-constituted as a different sort of person.

Many of the social ills that tech companies are blamed for are, in my opinion, better understood as effects of Cambridge power – or, to return to the academic language, ‘structural’ and ‘constitutive’ power. In no time at all, the proliferation of smartphones has changed the everyday habits of billions of people: seven out of ten Americans sleep with their phones on the bedside table, in bed with them or in their hand; for four out of ten people in the UK, checking their phone is the last thing they do before going to sleep at night and the first thing they do when they wake up in the morning. It can be hard to remember what people did when using public transport before there were smartphones to look at. At the same time, the emergence of social media has encouraged people to expose more of themselves than ever before, and to perform idealised versions of their own lives. The ubiquitous phenomenon of the selfie is one product of these shifts. More than 90 people die every year taking selfies, typically falling off cliffs or being run over by vehicles. Selfies now account for more deaths than lightning strikes, shark attacks and train crashes combined. In death as in life, we have become different sorts of people.

None of this was willed by tech entrepreneurs. Steve Jobs didn’t mastermind a plan to make people so obsessed with their iPhones that they can’t bear to be separated from them. Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger didn’t found Instagram with an elaborate theory of how they would get people to document their breakfast, and they didn’t invent the selfie. Rather, they noticed some of the ways human life was being mysteriously reshaped, and responded to them. These responses – iOS notifications or the Clarendon filter, for example – had a shaping effect of their own. Tech companies benefit from and contribute to structural and constitutive power, but they aren’t the source of it. As a result, it’s no more possible to identify the app that caused trolling, cyberbullying or online self-harm than it is to locate the person responsible for the woes of my first term in Cambridge. It’s no more appropriate to blame big tech for your wasted screen time than to blame ‘big coffee’ for your daily flat white, an expensive habit that you somehow find yourself in thrall to.

What are we to do about this type of power? It might not originate with any individual, product or company, but it still has major effects on us. For Foucault, the answer lay in practices of self-care. The power that compels us to touch our phones thousands of times a day, check WhatsApp during a family dinner, or rage-tweet a public figure can’t be escaped, but we can win a measure of freedom by training ourselves to resist it. With digital technology as with artisan coffee or being a mature student, that training starts with noticing the strange ways power is operating and making conscious choices in spite of it.

Market Power

Another type of power that can help us understand power relations in the age of big tech is more straightforward: market power. Unlike structural and constitutive power, market power is held and deliberately wielded by tech companies to advance their interests.

Many manifestations of market power are obvious, like the lobbying of governments, and here, there is no essential difference between tech companies and other large corporations. Between them Apple, Amazon, Google and Facebook spend roughly the same as the major players in financial services, defence and the car industry on lobbying in Washington, DC (some $55 million in 2018, in case you were wondering). For better or for worse, lobbying is just a thing big companies do.

An insatiable appetite for acquiring competitors is another obvious and familiar manifestation of market power. However, comparisons between big tech and other industries are complicated by the fact that consolidation in the tech industry does not tend to lead to consumers paying higher prices. Since the 1970s, consumer welfare – understood narrowly as what is in people’s short-term financial interests – has been the main factor competition regulators have considered when deciding whether to approve mergers and acquisitions. A single player in the automotive industry would not be allowed to own four of the top six global car brands, because that would enable it to increase its profit margins at consumers’ expense. By contrast, Facebook’s ownership of four of the top six social media apps, enabled by its multi-billion-dollar acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp, is acceptable because it doesn’t appear to make consumers financially worse off – in large part because the services are free.

Nevertheless, the use of market power by tech companies to increase their market share is a cause of concern for scholars, commentators and policymakers. In the West, we tend to be instinctively suspicious of concentrations of power, and I think it’s this suspicion that leads people to give so much credence to the idea of digital Panopticons and to surveillance capitalism theory: powerful tech companies don’t appear to be ripping us off, so they must be exploiting us in some other more sophisticated and covert way.

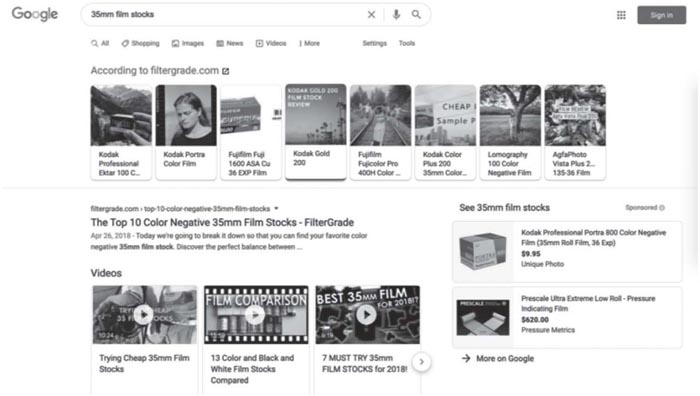

However, there is a category of people who suffer the effects of tech companies’ market power: business owners. Take brothers Mike and Matt Moloney, whose business FilterGrade provides a marketplace for photographers to buy and sell digital photo-editing tools. The FilterGrade website contains a great deal of useful original content that helps photographers use these tools and learn new techniques – Mike and Matt use search data to understand what their users are looking for, and create content to serve these needs. As a result, Google rewards them with prominent positions in its search listings. However, Google also does something else: it extracts words and images from the FilterGrade website and uses them to enrich its search results with so-called ‘featured snippets’. In some contexts, having a featured snippet can be a huge blessing for a business – if you google ‘What does dog insurance cost?’, you’ll see how it helps Bought By Many. But where Google has monetisation opportunities, it can be a curse.

In April 2020, Mike found that Google was populating a featured snippet for the search ‘35mm film stocks’ with content from the FilterGrade website (pictured opposite). However, because of the user interface design of the search results page, there was almost no chance that a user would click through to FilterGrade’s website – instead, the links in the image and video carousels funnelled users towards ads in Google Shopping and YouTube.

A ‘featured snippet’ on Google’s results page which uses FilterGrade’s content.

Although this particular piece of user interface design has since been deprecated, Google has a history of exercising its market power in similar ways. It once acquired a financial price comparison platform and integrated it into search results for loans, credit cards and mortgages, earning commission income from clicks that otherwise would have gone to third-party websites. It did the same thing in the flight comparison market by acquiring the company ITA Software for $700 million and turning it into Google Flights. Search for ‘flight to San Francisco’ on Google, and a Google Flights integration will take up as much of your screen as links to third-party websites like Kayak and Skyscanner.

These exercises of market power are made possible by vertical integration – that is, the control of different parts of the value chain in an industry by the same company. It’s a strategy that goes back 130 years to Andrew Carnegie, the Scottish-American steel magnate who owned mines, ships and railways as well as steel mills. As a result, he had more market power than his competitors, who depended on the transport infrastructure he controlled. If he wanted to drive them out of the steel business, all he needed to do was increase freight prices until their profit margins disappeared. In our own time, vertical integration isn’t particular to Google – it’s a feature of all the big tech companies. At the time of writing, Amazon is under investigation by the EU Competition Commission, having been accused of exercising market power to the detriment of third-party sellers on its Marketplace platform. Amazon operates Marketplace while simultaneously acting as a merchant, listing its own products alongside those of its advertiser clients. It appears to have used sales data gleaned from its role as Marketplace operator to decide what products to sell in its role as a merchant. Similarly, Apple operates the App Store, meaning it has the ability to give apps built by its own developers preferential treatment.

Market power is less exciting to read about than the disciplinary power of the Panopticon, meaning there’s a danger that it will get lost in the fog – like the supply chain and content moderation issues we discussed in Chapter Five. What’s more, preventing the misuse of market power requires us to scrutinise boring and often technical details about how tech companies act in relation to smaller businesses, many of whom are their clients. Too much concern with ‘our’ data can be an obstacle to such scrutiny as well as a distraction from it. Remember the US Congress investigation into anti-competitive practice in Google search, mentioned in Chapter Four? To quantify the impact of Google’s vertical integration on businesses like FilterGrade, we need data that shows the number of users clicking on links in Google results. But because of privacy concerns about Jumpshot compiling anonymised records of people’s internet behaviour, such data is no longer available. As the saying goes, we have cut off our nose to spite our face.

Reach Power

The final type of power that can help us make sense of digital power relations is newer and more distinctive. It is also less well theorised – in fact, it doesn’t even have a name. Let’s call it reach power.

Market power is concentrated with a small number of companies, and is tractable in nature – it can be deliberately exercised to advance an agenda. The more mysterious structural/constitutive power is diffused throughout society, but is intractable – it can be tapped into, but not used as a tool in the same way that market power can. Reach power, on the other hand, is a type of power that is both tractable and diffused throughout society.

I’m calling it reach power because it enables you, me and everyone else with a reliable internet connection to reach billions of other people. It’s the power to document, network, broadcast, convene, celebrate, endorse, cajole, influence, persuade, agitate, insult, harass and incite – on a global scale. Reach power is channelled through an incredibly sophisticated array of hardware and software, ranging from mobile phone video cameras to the Facebook Lookalikes algorithm. It is so widely distributed that it could be described as even more democratic than democracy itself: unlike voting rights, it has no minimum age, and it’s available in the fifty-nine countries around the world that are ruled by authoritarians. It can be harnessed in profound or trivial ways, for political purposes or for commercial ones, for good or for evil. Many of this book’s examples of reach power attest to this duality. I used the reach power of targeted ads to recruit diabetics and pug owners to early Bought By Many groups; Dominic Cummings used it to persuade people to vote Leave. WorldStores used the reach power of Google search to corner the market in trundle beds; Patrick Berlinquette used it to track the spread of Covid-19. Evan Mawarire used the reach power of social media to disseminate messages of protest against the failures of Robert Mugabe’s government; supporters of Rodrigo Duterte used it to legitimate extrajudicial killings. MoveOn used the reach power of Facebook pages to petition Mark Zuckerberg to shut down his Beacon programme; Burmese army officers used it to incite the Rohingya ethnic cleansing.

This duality of reach power explains many of the contradictions of the digital age: why we see the same technologies creating both freedom and oppression; stirring up both compassion and hatred. Returning to the idea of the Panopticon, we live in a world in which the inspector’s lodge – the privileged position from which power can be wielded in any direction – can be occupied by literally anyone. It’s so democratic as to be anarchic: it’s a free-for-all. We saw in Chapter Two that it is the absence of controls on who can use Facebook’s targeting technologies that causes political problems rather than the technologies themselves. The same is true of the other instruments of reach power, from YouTube channels to Twitter hashtags and WhatsApp groups. The question is, how can we curb the abuses of reach power without also losing its socially beneficial effects?