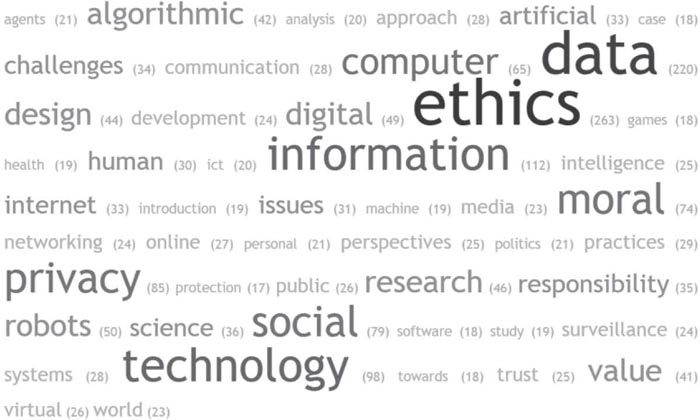

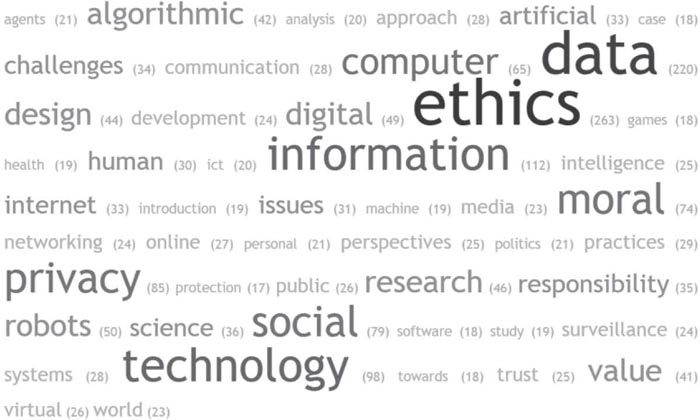

Word cloud visualisation of all the article titles in my database of academic literature on data ethics, with frequencies shown in brackets.

DATA ETHICS FOR BIG TECH

Big companies have self-interested reasons to care about legitimacy – not least because when governments decide they are too powerful, they tend to be fined, regulated, broken up or even nationalised. But do companies have moral responsibilities, that their executives should pay attention to even when there is little prospect of government intervention? Neoliberals don’t think they do; for them, companies’ only duties are to act in the interests of their shareholders and to obey the law. Talk of ‘business ethics’ is nonsensical.

That might be a valid position in principle but in practice it’s untenable, for the simple reason that big companies’ share prices are affected by the ethical concerns of the public. It’s common for journalists, NGOs and activists to highlight issues such as the poor treatment of workers and environmental degradation, while tax avoidance and regulatory arbitrage are increasingly regarded as unethical, irrespective of their legality. And historically, the involvement of corporations in catastrophes has materially damaged shareholder value. This isn’t just a matter of financial losses from reduced sales or from paying compensation for fatalities and injuries; when a company’s management is perceived to have been responsible for lapses in safety, there is a long-term negative impact on its share price that can amount to billions of dollars.

In 1982, seven people died of cyanide poisoning in Chicago, after taking capsules of the painkiller Tylenol that had been tampered with. Shares in the drug’s manufacturer, Johnson & Johnson, lost 10 per cent of their value almost immediately, and a further 8 per cent over the next four months. Following the 1989 oil spill from the Exxon Valdez tanker, the company’s share price followed the same trajectory: it was 15 per cent down fifty days after the spill, and 18 per cent down after six months. And Union Carbide, the chemical company responsible for the toxic gas leak at Bhopal in 1984, which caused up to 16,000 deaths, lost 29 per cent of its value in the same time frame.

The implication is that ethics is important for all big companies, whether they like it or not. So what should the CEOs of big tech companies pay particular attention to? The short answer is a new field called ‘data ethics’. Between the 1970s and the 2000s, technology ethics tended to be discussed either at the level of computers or of their human designers and users. The term data ethics has been coined to reflect the fact that in the digital era, many ethical questions need to be discussed at the level of data. As part of a recent project with my Cambridge colleagues, I compiled a database of 953 peer-reviewed journal articles on data ethics, and used the ‘data photography’ technique I described in Chapter Three to reveal what those questions are. If you stare at the visualisation for long enough, you can see the key themes of data ethics emerge. We’ve examined some of them already, including privacy, surveillance and software user interface design. But now it’s time to touch on some of the others.

Word cloud visualisation of all the article titles in my database of academic literature on data ethics, with frequencies shown in brackets.

Bias, Discrimination and Injustice in Algorithmic Decision-making

Like targeted advertising, the use of algorithms – rather than humans – to make important decisions is not a new phenomenon. Ever since the 1980s, financial services companies have used automated scoring to decide whether to accept or reject applications for loans, credit cards, car finance plans and mortgages. Drawing on data held in credit bureaus, scorecards had supplanted bank managers as the chief decision makers on the extension of credit by the turn of the century, while similar models were adopted by direct-to-consumer insurance brands to automate their underwriting decisions.

Prior to the subprime mortgage crisis in 2008, the use of algorithmic decision-making in financial services wasn’t widely regarded as an ethical issue. However, the proliferation of data and advances in machine learning have enabled algorithmic decision-making to be extended to other domains, including criminal justice and policing – often facilitated by tech companies like Palantir, as we saw in Chapter Seven. In the criminal justice system, algorithms that predict the likelihood criminals will reoffend are used in sentencing and parole decisions, while ‘predictive policing’ models are used to determine where law enforcement personnel should be deployed in anticipation of potential crimes.

However, researchers have demonstrated that the unconscious biases of algorithm designers and their models’ reliance on historic data can reproduce racial, ethnic and gender discrimination. In her excellent book on the subject, Weapons of Math Destruction, Cathy O’Neil gives the example of LSI-R, an algorithm used by courts in some US states to estimate the likelihood that prisoners will reoffend. One of the data points the algorithm uses relates to involvement with the police at a young age. ‘Involvement’ might mean committing a crime, but it also encompasses being on the receiving end of a stop and search encounter, which is far more likely to happen to young men of colour. In New York City, Black and Latino males aged between fourteen and twenty-four account for less than 5 per cent of the population, but more than 40 per cent of those stopped and searched by the police. As a result, LSI-R makes parole and sentencing recommendations that are informed by human police officers’ perception that people of colour are more likely to commit crimes.

So far, tech companies’ efforts to mitigate the risk of such injustices have come in the form of resources for algorithm developers. Facebook has an internal tool called ‘Fairness Flow’ that measures how algorithms affect specific groups; Google has released the ‘What-If Tool’, which is intended to help developers identify biases in data sets and algorithms. IBM has gone a step further with AI Fairness 360, an open-source toolkit that is designed to check for and mitigate unwanted biases embedded in algorithms and the data used to train machine learning models. These are all steps in the right direction, but tech companies might also need to accept that they have a moral responsibility to make their algorithms transparent and explainable – not just to lawmakers, but to the individuals who are most affected by them.

Artificial General Intelligence as an Existential Risk to Humanity

In the view of a large number of AI experts surveyed by researchers in 2017, there is a 50 per cent chance that AI will outperform humans in all tasks by 2060. Although there is disagreement among the experts about how imminent this situation is, its severity is more certain: human intelligence is constrained by the information-processing limits of biological tissue, but machines are not subject to the same limits. According to Nick Bostrom and his colleagues at the University of Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute, AI poses an existential threat to human survival.

This threat can be illustrated with a simple thought experiment, borrowed from Jamie Susskind’s Future Politics. Imagine a machine superintelligence was given the objective of calculating Pi. Optimising towards its goal, it could be expected to channel all the world’s resources into building a planet-sized supercomputer; and since humanity serves no useful computational purpose, we could expect to be wiped out entirely or instrumentalised (think of The Matrix, where people are used as batteries). Bostrom therefore stresses the importance of ensuring that the objectives of AI systems are both aligned with human values and rigorously specified.

Many tech companies have set up AI ethics boards in recent years, with executives’ personal views on existential risk often providing the motivation. Elon Musk has tweeted that he thinks AI is more dangerous than nuclear weapons, while the founders of DeepMind made the creation of an AI ethics and safety board a condition of their acquisition by Google.

However, there are reasons to be sceptical of this trend. The sudden proliferation of ethics boards at tech companies has led to accusations of ‘ethics washing’ – the disingenuous engagement with ethics as a PR strategy, similar to the ‘greenwashing’ that companies with poor environmental records have undertaken in the past. As the AI researcher Meredith Whittaker points out, even Axon, which manufactures taser weapons, surveillance drones and AI-enhanced police body cameras, now has an ethics board, the establishment of which is clearly not a sufficient response to the ethical issues raised by the company’s business activities. Unless ethics boards have the authority to veto product decisions and hold executives to account, they are no more than ‘ethics theatre’. The same is true of moves by tech companies to publish ethical principles and appoint chief ethics officers: without tangible evidence that they are driving ethical actions, they are likely to lack credibility.

Salesforce is a good example. The company states that it has ‘a broader responsibility to society … to create technology that … upholds the basic rights of every individual’. In 2018, it appointed Paula Goldman as chief ethics and humane use officer, with a remit to understand the impact of the company’s products on the world, create an ethical internal culture and product design process, and advance the field of data ethics through dialogue with stakeholders. However, that hasn’t stopped Salesforce facing the same ongoing criticism as Palantir over its contract with the US Customs and Border Protection Agency, which implicates it in alleged inhumane treatment of migrants at the US southern border.

Similarly, in 2019, Google’s AI ethics board closed a week after launching, amidst criticism over the appointment of a board member who had illiberal views on minority rights. This suggested significant gaps in Google’s thinking on AI ethics – not least their failure to realise that algorithmic injustice is more of a clear and present danger than machine superintelligence.

Job Displacement from Machine Learning and Robotics

In 2013, research by the economists Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne suggested that 47 per cent of American jobs were at high risk from computerisation. Their paper precipitated a wave of reports and studies on ‘the future of work’, receiving over 5,000 academic citations. Longer-term prospects for jobs appear even more bleak: the survey of AI experts mentioned earlier suggests there is a 50 per cent chance that machines will have displaced all human jobs by 2140. So central is work to our sense of identity, that job displacement is an existential question, as well as an economic one. It has been suggested that tech companies which prosper from automation have a moral duty towards the workers whose livelihoods it puts at risk.

Tech CEOs seem somewhat sympathetic to this view. The Partnership on AI, a non-profit think tank founded by Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft and IBM, has addressed questions of job displacement in its research. Consistent with his hypothesis about the pace of advancement in AI, Elon Musk has supported calls for a universal basic income, as have Pierre Omidyar, founder of eBay, and Sam Altman, who runs the influential Silicon Valley start-up accelerator Y-Combinator. At a 2017 meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, the Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella remarked that ‘We should do our very best to train people for the jobs of the future,’ while his counterpart at Salesforce, Marc Benioff, spoke of his fear that AI would create ‘digital refugees’. However, while job displacement may be a concern of tech company CEOs and a focus for conference speeches and philanthropic activity, so far there has been little tangible action by tech companies to mitigate it.

Reconciling Differences in the World’s Ethical Traditions

One complication for big tech companies in thinking about data ethics is the existence of different ethical traditions in the countries where they operate. The world’s main ethical traditions include the Islamic tradition, the Confucian tradition, the Indian tradition and the Buddhist tradition, as well as the Western or Judaeo-Christian tradition.

Even in this far-from-exhaustive list, there is significant divergence on matters of business ethics. Trust-based relationships may be viewed as more or less important than legal contracts. Favouritism towards family members may be regarded as a virtue or as a vice. Furthermore, there is also divergence within ethical traditions. For example, America emphasises the virtue of self-reliance, while Europe emphasises the duty to look after the needy. In the Islamic tradition, law is interpreted based on local context, which leads to variations in ethical conduct.

However, there are also significant points of convergence. Fulfilling duties and treating people as you would wish to be treated are universal virtues. This ‘Golden Rule’ is familiar to readers of the Bible, but it also appears in The Analects, the collection of Confucius’ sayings and ideas.

At the same time, harming people, stealing, telling lies and committing fraud are universally regarded as vices. As a result of these points of convergence, it has been possible to determine universal minimum ethical standards for multinational business activities – more or less everyone believes in respecting human dignity and basic rights. As a result, minimum ethical standards include ensuring products, services and workplaces are safe; upholding individuals’ rights to education and an adequate standard of living; and treating employees, customers and suppliers as people with intrinsic value rather than as a means to an end. Similarly, it’s generally accepted that companies should support essential social institutions like the education system and work with governments to protect the environment.

These standards were developed with industries such as pharmaceuticals, oil and chemicals in mind, and following disasters like the Tylenol poisonings, the Exxon Valdez oil spill and the Bhopal gas leak. As we’ve seen, digital technology raises new questions, and it is unrealistic to expect that they can be fully addressed by applying existing ethical standards. However, I’m optimistic that an ‘overlapping consensus’ on data ethics can be achieved, and the story of Shanghai Roadway brings this idea to life.

Shanghai Roadway was a Chinese subsidiary of the American data company Dun & Bradstreet, which provides data and analytics to around 90 per cent of the companies on the Fortune 500. Until it was bought out by private equity investors in 2019, Dun & Bradstreet was listed on the New York Stock Exchange; in 2017, it had revenues of $1.7 billion. It acquired Shanghai Roadway in 2009 as part of a strategy to expand in the Chinese market. Like many other divisions of the company, Shanghai Roadway marketed data about businesses and consumers to lenders and other commercial clients, generating revenues of $23 million in 2011.

However, Shanghai Roadway’s data collection practices were to result in controversy. In common with the business model of other data companies such as Experian, Shanghai Roadway sourced data on individuals to populate its databases through commercial relationships with banks, insurance companies, real estate agents and telemarketing companies. The company held personal information, including income levels, jobs and addresses, on approximately 150 million Chinese citizens, with records from this database sold for around $0.23 each to companies as marketing and sales leads.

In September 2012, the Shanghai District Prosecutor charged Shanghai Roadway and five former employees with illegally obtaining private information belonging to Chinese citizens. The court fined the company the equivalent of $160,000 and sentenced four of the former employees to two years in prison. The basis for the decision was a 2009 amendment to the criminal law, which made it illegal for companies in the financial services, telecommunications, transport, education and healthcare industries to obtain or sell a citizen’s personal information. Following the judgment, Shanghai Roadway ceased trading and Dun & Bradstreet reported itself to US regulators. In April 2018, Dun & Bradstreet agreed to pay a $9 million fine to resolve charges under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, relating to payments made to third-party agents who had procured data on Shanghai Roadway’s behalf, and to the bribery of government officials by another Chinese subsidiary of Dun & Bradstreet to facilitate access to personal data.

The significance of the Shanghai Roadway case is that it demonstrates an ‘overlapping consensus’ on a real-life question of data ethics. Chinese and US prosecutors agreed that Shanghai Roadway had acted unethically and sanctioned Dun & Bradstreet accordingly, but they did not agree on what aspect of Shanghai Roadway’s conduct was unethical. In China, it was its business model of collecting and selling personal data without informed consent, while in the US, it was the practice of making off-book payments to intermediaries and government officials. The former is ethically acceptable in the US – indeed, there is a $2.6 billion industry, digital lead generation, devoted to it. And in the context of Chinese norms around gift-giving, the latter can be perceived as an honourable way of investing in a long-term business relationship, rather than an unethical instance of bribery.

Beyond the Trolley Problem

Of course, religious traditions aren’t the only basis for ethics. The recent development of self-driving cars by big tech companies like Google, Tesla and Uber has put philosophical ethics in the spotlight.

Globally, road traffic accidents accounted for 1.4 million fatalities in 2016. While developers of autonomous vehicles claim they will have a net favourable impact on road safety by reducing human error, it’s inevitable that their adoption will lead to fatal accidents. Indeed, at the time of writing, Tesla’s automated driving system has already caused five deaths, and Uber’s has caused one. This raises an ethical question about the software used to determine how a self-driving car should react in the event of a probable collision. Programmers are presented with a version of the ethical dilemma famously framed by the philosopher Philippa Foot as ‘the trolley problem’.

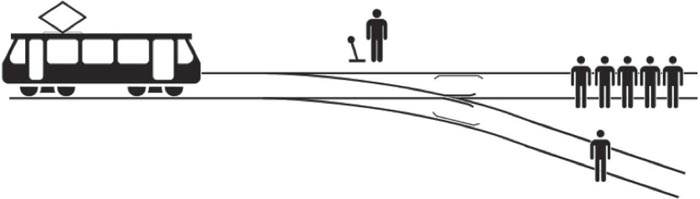

The trolley problem is a thought experiment involving an out-of-control train that’s heading towards five people, who are unable to move and will be killed in the collision. Imagine you are standing next to a set of points between the runaway train and the people. By pulling a lever, you could divert the train onto a second track, killing one person instead. Should you pull the lever?

The problem captures the divergence of views between two of the main schools of philosophical ethics – utilitarianism and deontology. As we saw in Chapter Six, utilitarianism weighs up the consequences of an action to determine whether it is ethical or not. If Jeremy Bentham was standing at the points he would pull the lever, on the basis that the happiness created by saving five lives would more than offset the happiness destroyed by causing one death. By contrast, the competing theory of deontology, which is associated with Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), says that all actions are right or wrong in and of themselves. Kant would not pull the lever to divert the runaway train, on the basis that it is one’s duty not to kill, regardless of any extenuating circumstances.

The Trolley Problem: should you divert the train?

With many human lives potentially at stake, academics have argued that the decision about which theory of ethics is encoded into autonomous vehicle software should not be left up to the programmers. It’s not even a straightforward binary choice: software operating on utilitarian principles would need to know whether to prioritise the life of the passenger against the lives of pedestrians and passengers in other vehicles. And if we apply these theories to the case of Shanghai Roadway, it’s hard to see how either a strictly deontological or utilitarian approach to data ethics would be feasible. Deontology requires the determination of whether actions are right or wrong in and of themselves, leaving no room for variations in norms in different regions of the world. Utilitarianism, meanwhile, requires us to weigh up the consequences of different actions, and even in the relatively simple example of Shanghai Roadway’s procurement of personal data, it is difficult to make this calculation. What proportion of the Chinese citizens whose data was traded by Shanghai Roadway experienced harm, whether through unwanted phone calls or messages or in more serious forms? What economic benefits did Shanghai Roadway’s clients gain from using the data, and how much of those benefits flowed on to their own clients, shareholders and employees? How are these harms and benefits to be quantified? More complex questions – in relation to the development of the algorithms used in the criminal justice system, for example – are even more resistant to the calculations utilitarianism requires.

Luckily, there is another theory called virtue ethics, which goes all the way back to ancient Greece and the thinking of Aristotle (c.384 BCE–c.322 BCE). For Aristotle, ethics should be less concerned with specific actions than with the character of the person or organisation who carries them out.

In the trolley problem, whether or not it is ethical to pull the lever therefore depends on the circumstances of the person faced with the choice: pulling the lever might express the virtue of bravery or the vice of megalomania. When applied to data ethics, virtue ethics suggests that tech companies should ask themselves: ‘What kind of company should we be?’ In the Shanghai Roadway case, Dun & Bradstreet might have asked, ‘Do we want to be the sort of company that covertly gains access to personal data by making off-book payments?’ Posing this question helps to identify what may be a universal virtue of tech companies: transparency. Acting transparently would have required them to both make it clear to consumers how data about them might end up in a commercially available marketing database, and to eschew extra-contractual arrangements with suppliers and intermediaries.

Cloudflare’s decision to withdraw services from 8chan, a message board associated with white supremacist and neo-Nazi ideologies, offers an example of virtue ethics in practice. Cloud-flare is a San Francisco-based web infrastructure company that provides cloud security, protecting websites from cyberattacks. It supports over 19 million websites for clients including IBM, Thomson Reuters and Zendesk.

Until 2019, 8chan was one of Cloudflare’s clients. Historically, Cloudflare saw itself as a neutral utility service, and it didn’t make judgements about its clients based on the content of their websites. This position could be justified from a deontological or a utilitarian perspective: one could argue that it is wrong for a private company to censor speech, or that removing a client like 8chan might lead, say, to pressure from governments to remove websites belonging to unfavoured minorities. However, when it became clear that the perpetrator of a mass shooting in El Paso, Texas in August 2019 had posted a manifesto on 8chan, Cloudflare’s CEO Matthew Prince changed his stance and terminated their contract with 8chan. In a blog post on Cloudflare’s website, he wrote:

We do not take this decision lightly. Cloudflare is a network provider. In pursuit of our goal of helping build a better internet, we’ve considered it important to provide our security services broadly to make sure as many users as possible are secure, and thereby making cyberattacks less attractive – regardless of the content of those websites. Many of our customers run platforms of their own on top of our network. If our policies are more conservative than theirs it effectively undercuts their ability to run their services and set their own policies. We reluctantly tolerate content that we find reprehensible, but we draw the line at platforms that have demonstrated they directly inspire tragic events and are lawless by design.

Cloudflare, it seems, wants to be the kind of company that upholds net neutrality as far as is possible without undermining the rule of law. It is also worth noting that by writing publicly about his decision and by giving interviews to journalists about it, Prince exhibited the virtue of transparency.

If virtue ethics is the framework that makes the most sense for big tech companies, how should they apply it? To think through this, let’s consider an imaginary provider of telecoms infrastructure and hardware. Seeking revenue growth, this provider might consider diversifying into so-called ‘value added services’ such as messaging apps, location services, Internet of Things analytics and mobile advertising. All these services involve the collection and storage of personal data: even end-to-end encrypted messaging produces metadata that could contribute to the identification of individual users; and even business-to-business Internet of Things apps could capture data on individual employees via sensors. At the same time, storing personal data from these services creates the risk that it may be misappropriated by ‘bad people’ and used for harm.

In short, providing value added services risks individuals being exposed to harm. In addition, as data protection legislation typically lags behind advances in digital technology, the law cannot be relied on for guidance. One potential response might be to adopt best-practice data protection standards. These would include ensuring that individuals give informed consent for data collection and are able to withdraw it in future, and the principle of ‘data minimisation’, which means collecting only the data that’s required for the services to function effectively.

Further issues would arise if the data produced by providing value added services was put to secondary uses, such as using location data to target advertising or packaging Internet of Things data from smart home devices as an analytics product. Since secondary uses are often unknown at the point of data collection, they are in tension with the principle of consent. Similarly, big data analytics is in tension with the principle of data minimisation, as it is based on the serendipitous discovery of correlations in very large data sets.

At the same time, the development of value added services can have unintended consequences. Location services have been used by perpetrators of domestic abuse to track down their victims. Livestreaming services have been used to broadcast footage of self-harm, suicide and mass killings. Encrypted messaging services have been used to circulate images of child sexual abuse and to plan acts of terrorism.

Do such unintended consequences imply that it would be unethical for the telecoms company to develop new products in these areas at all? And do the best practices imply that value added services can only be ethical if their scope is tightly circumscribed? I don’t think so, as that ignores the benefits the services bring to large numbers of users and clients, and it forecloses on opportunities for data analytics to create public value – imagine, for example, that smart home analytics enabled major advances in domestic energy conservation that could significantly reduce carbon emissions. Instead, asking ‘What kind of company should we be?’ can help strike a balance between pursuing innovation, growth or profitability at any cost and the inertia that often follows when we get risks out of proportion.

The Virtuous Big Tech Company

So, what should big tech companies actually do about data ethics? Governance is a good place for them to start. Expanding the scope of their compliance function to ‘ethics and compliance’ would acknowledge that all companies have broader social responsibilities than simply complying with the law and mitigating regulatory risk, and that the distinctive power that tech companies have only heightens these responsibilities. If a group is established with responsibility for data ethics, it should have a formal role in the company’s governance structure, including rights to veto product decisions. Without these rights, ethics boards will struggle to transcend ‘ethics theatre’. At the same time, the board’s scope should not be limited to AI. As we’ve seen, data ethics questions run broader and deeper, and many are more immediate than the threat of machine superintelligence.

Tech companies could also use ethical frameworks when evaluating whether to terminate client relationships that may be enabling unethical practices – Salesforce and Palantir’s relationships with the US Customs and Border Protection Agency being a current example. These are rarely straightforward decisions, but deliberating on them in public, as Cloudflare did on 8chan, is a virtuous thing to do. Meanwhile, where practical questions of data ethics are complicated by differences in ethical traditions and norms, as was the case with Shanghai Roadway, ‘overlapping consensus’ may be achievable and should certainly be pursued.

Returning to the themes of previous chapters, companies also have an ethical imperative to provide transparency to individuals over how their personal data is collected, stored and used, and to offer tools enabling them to exercise control over it – like Google’s Safety Center and Facebook’s Ad Preference Center. Meanwhile, the suitability of ‘engagement’ metrics as business targets should be reviewed, as they may be misaligned – or even at odds – with users’ wellbeing. And new products should be developed with due consideration for both data-related risks and potential unintended consequences, rather than by fostering a culture of ‘permissionless innovation’ where anything goes.

But as well as working to reduce risks of harm, a virtuous tech company would also try to maximise the good it did in the world. What positive actions might it take?

‘Co-creating’ the Jobs of the Future

Automation is not the only driver of disruption to work; as the emergence of the term ‘the gig economy’ indicates, the labour market is becoming more flexible and more volatile. Although there has been no shortage of corporate research initiatives on ‘the future of work’, most tangible interventions have come from start-ups and social enterprises responding to the increasing insecurity of employment. There is, therefore, an opportunity for tech companies who seek to enable human flourishing to proactively fashion the jobs of the future – jobs in which humans and machines are not in competition, but instead collaborate in a way that both enhances performance and enriches human life. Precedents for this form of working already exist. Machine learning algorithms can be as effective as experienced doctors at diagnosing some forms of cancer, pointing to a future for medical professionals in which human clinical experience is complemented by AI’s strengths in pattern recognition and data processing speed. However, opportunities also exist in less specialised types of work that employ far more people. One example is the food delivery sector, where tech companies such as Deliveroo and Alibaba’s Ele.me have created high-growth businesses by combining mobile apps, logistics and casualised labour. Ethnographic research has revealed a somewhat adversarial relationship between human couriers and the algorithms used to assign jobs and plan routes. In face-to-face conversations and in WhatsApp groups, couriers collaborate in an attempt to reverse-engineer the algorithm, iteratively testing strategies to optimise their earnings. Meanwhile, isolated in a head office where they never interact with the couriers, the algorithm’s developers build new features based on assumptions about their users’ needs that the couriers know to be flawed.

A ‘co-creation’ approach offers the potential to redesign the relationship between human workers and AI to be more harmonious and more economically productive. The process involves bringing together groups of stakeholders to work collaboratively on a solution. In the case of food delivery, these stakeholders would be the couriers, the algorithm developers and users of the apps. Although co-creation is usually associated with the development of new consumer products and services, it has been proposed as an approach to help map the future of work at Mondragón in the Basque region of Spain, where automation and the need for a green transition are creating uncertainty for large numbers of manufacturing and construction workers. Tech companies could undertake co-creation processes with their own employees in fields that are at risk of technological displacement, or with people whose employability is threatened by their products. Millions of workers in fields like customer services, social media content moderation and device manufacture could benefit from new kinds of jobs designed through such initiatives.

Putting More Data into the Public Domain

Tech companies with data-driven business models tend to reject the assertion that the services they provide are worth less than the user data they monetise; as a result, they have not generally explored the idea of compensating users for data. In my opinion, there are both philosophical barriers to treating data as private property and practical barriers to paying users for data. Nevertheless, the kind of tech companies who want to enable scientific progress and social justice could consider sharing data value in a different form. Specifically, I want to propose that tech companies make a greater proportion of the data they have collected openly available for researchers, policymakers and members of the public to reuse.

What sort of data do I have in mind? As ever, internet search data provides a helpful example. The limited search data that Google already makes available through Google Trends is demonstrably valuable for academic research; in public health, it has already been used to analyse the symptoms of fibromyalgia and the seasonality in domestic violence, and to forecast transnational migration flows and the spread of coronavirus. However, Google Trends provides very little data on search term variations – the data that shows exactly what users search for when they are searching on a particular topic. It is deep search term variation data that holds untapped insights into public opinion, attitudes, preferences, needs, desires and behaviours. As much of this data has negligible value to advertisers – think of the hundreds of millions of searches for state benefits, for example – there is little commercial reason for tech companies to hoard it. It is not only search engines like Google, Baidu and Bing that are able to capture internet searches: web browsers, browser extensions, anti-virus software applications and internet service providers are, too. Making more search data openly available – in de-identified and aggregated form – is one way that tech companies can promote public good. The same argument can be made about de-identified and aggregated location data, Internet of Things data and clickstream data – behavioural data about which websites users visit and in what sequence.

Regrettably, however, this is not the prevailing trajectory. Google recently deprecated Google Correlate, which enabled researchers to see what search terms were correlated with their own time series data sets. Similar trends are apparent in relation to social media data from Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Motivated in part by calls for stronger privacy controls in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, researchers’ access to data sets is increasingly constrained – a development sometimes referred to as the ‘APIcalypse’. Beyond academia, as we saw in Chapter Five, open-source intelligence organisations that rely on access to social media data for their investigations into potential war crimes and human rights violations have found their work hampered by the deletion of video archives by YouTube and the withdrawal of tools like Facebook Graph Search and Google Earth’s Panoramio layer.

It seems likely that tech companies are simply ignorant of many of the beneficial uses of the data they already share and cannot imagine the uses that might be found for data they hoard. These could include scientific advances, medical breakthroughs, criminal prosecutions and public policy innovations. A virtuous tech company would seek to unlock those opportunities, not to foreclose them.