A DECADE HAS passed since we wrote the first edition of this book. Clearly, the executives who met with us in 2008 were prescient. The problems we read about in today’s headlines reflect the force of the disruptors they identified. Parts of the global banking system are still unstable, and new derivative instruments pose problems. Trade war is under way. Inequality has proved to be as disruptive a political force as the executives had imagined. Migration is a crisis both across borders and within countries. The effects of environmental change are regularly in the headlines. The rule of law is breaking down, and corruption is more pervasive. In the richer countries, public health and education are weaker in ways that matter. Pandemics threaten. It is even more obvious that state capitalism and market capitalism are uneasy neighbors. And as noted in the preface to this edition of the book, the explosive growth of digital information and communication has enabled the emergence of powerful new threats to security and political stability.

This chapter begins with a review of the ten disruptors that worried the executives we spoke with in 2007 and 2008. The intervening decade has revealed how these disruptors interact to create problems that are even more complex and intractable than those created by each disruptor alone. Four of these interactions are described later in this chapter. Finally, we describe how the continued inability or unwillingness of governments and multilateral institutions to deal with the disruptors creates ever-increasing risk for business and the market system.

That conclusion in turn leads us to expand on ideas from Part Two, about the role of business. In chapter 10, we examine four companies that have developed strategies for building their long-term success by directly addressing aspects of the disruptors. In chapter 11, we share some practical guidance that emerges from the successful efforts we have observed.

Disruptors Overwhelm Inadequate Institutions

The Financial System

The financial system collapsed between the time we conducted the research for this book’s first edition and its publication. The basic causes of the 2008 collapse were found in excessive levels of debt, particularly subprime mortgages in the United States that were used as collateral for a pyramid of new debt instruments. These instruments in turn made their way onto the balance sheets of banks around the world. The underlying mortgages fueled a real estate boom, and when masses of borrowers stopped paying on their mortgages, the pyramid collapsed, bringing down the balance sheets of the lenders—which included some of the world’s largest and supposedly most stable financial institutions.

In 2019, the balance sheets of banks had generally been restored, largely because central banks worldwide flooded the system with cash, propping up the asset prices underlying the banks, and partly because bank regulators tightened balance-sheet standards. Unfortunately, new forms of collateralized debt have appeared, and so-called nonbank lenders have emerged to meet the demand for credit by companies with poor credit ratings. Although the financial system today is by some measures more stable than it was a decade ago, new trouble spots have emerged and the ongoing stability of the system is far from assured.

Persistently low and even negative interest rates are evidence of the unusual position taken by central banks. If interest is the time value of money, it is not entirely clear what the implications of a negative interest rate might be. Banks holding cash clearly have an incentive to lend, but the negative interest rate is also a worrisome macroeconomic signal potentially auguring deflation. The very low rates are also a calamity—and a disincentive—for savers.

Ballooning pension obligations present a further problem. In the United States and some other countries, many state, provincial, and local government entities as well as corporations have pension obligations that far exceed their ability to pay. The Hoover Institution estimated the market value of unfunded state pension liabilities in the United States in 2017 at over $4 trillion.1 This sum surpasses by far the funds in the U.S. Pension Guaranty Corporation. The pensions of millions of those working for state and local governments are at risk. If an attempt is made to pay these retirees in full, a number of jurisdictions may find themselves bankrupt. If the pensions are not paid, then millions of retired people will see an important component of the savings they were relying on for their old age suddenly shrink.

The Trading System

The health of the trading system also receives a mixed assessment. The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has described international trade patterns over the last few years as being characterized “first by anemic growth (2012–2014), then by a downturn (2015 and 2016) and finally by a strong rebound (2017 and 2018).”2 The slowing of the global economy in 2019 was expected to result in lower trade numbers. However, the global trading system is functioning reasonably well when judged by (1) its ability to transition from one large global system dominated by China to a more complex set of regional networks and (2) from a trade mix that is primarily focused on materials and manufacturers to one dominated by services and intellectual property.3 (This evolution is discussed further in the next section.) A major change from 2008 to today is the reemergence of the United States as a net exporter of oil and gas and the rapid growth of renewable energy, although in the aggregate, production of renewable forms of energy is still only 15 percent of total consumption.4

The trading system is stressed, however, by uncertainty about international trade rules and by governments’ use of economic sanctions and tariffs to achieve political objectives. These governments’ high-stakes tit-for-tat “negotiations” threaten to undermine critical processes and relationships that sustain the trading system and that, if destroyed, will be difficult to rebuild. Trade will also be affected as the United Kingdom exits from the European Union.

Economic Inequality and Populism

Having emerged as central challenges in many countries across the world, economic inequality and political populism have moved from a potential disruptor in the past decade to be the center of a global political hurricane today. As discussed at greater length in the next section, the two decades running up to the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent recovery of the financial system left the middle class far worse off and the top 1 percent in many countries with staggering wealth. China now boasts 285 billionaires.5 In India in 2000, the share of income of the top 10 percent and the middle 40 percent were the same; by 2014, the top 10 percent had 55 percent and the middle 40 percent held 30 percent. In the United States, the top 1 percent of families control 38 percent of the wealth.6 Across the world, people in countries whose condition has not improved or has worsened since the 1970s have expressed themselves politically. The concerns of these groups have provided the energy behind a series of populist political movements.

Migration

Migration also developed into a global storm during the post-2008 period. Before 2008, migration had already been steadily increasing. Since that year, political violence in the Middle East, Africa, and Central America and environmental crises around the world have only exacerbated the trend. As of 2000, some 173 million people lived outside the nation of their birth; by 2017, the number had risen to 258 million.7 The United Nations reported that in 2018, over 70 million people were forcibly living outside their home areas: 26 million were refugees living outside their homeland, and another 41 million had been displaced to a different area of their home country.8

Environmental Degradation

Environmental degradation is now widely perceived as a potentially existential threat. The change in perception is due less to the scientific evidence of degradation—which continues to mount—and more to the persistent and pervasive occurrence of fires, typhoons, hurricanes, and floods over the last decade.9 In late 2019, Australia and California experienced catastrophic fires, and Venice, Italy; Jakarta, Indonesia; and Dhaka, Bangladesh, were flooded.

Failure of the Rule of Law

Primarily because of the failure of several states, the rule of law is increasingly losing ground. As long as kleptocracy was confined to Central Asia, the Balkans, and Central Africa, tribal chiefs or former Soviet bosses were described in the Western press as vestigial disturbances to global progress. But the last decade has seen major problems emerge in South Africa, Malaysia, Brazil, Venezuela, and Russia, countries that, while not thought exactly to be paragons of governance, were generally seen as improving. Some of these are captured states, the economic prize of a family or a clan. Others are simply oligarchic fiefdoms.10 Recent surveys show that perceived government corruption is a growing problem in the United States as well.11 In 2018, the United States dropped out of the top twenty in Transparency International’s ranking of countries (from least to most corrupt) by perceived levels of corruption.12

Public Health and Education

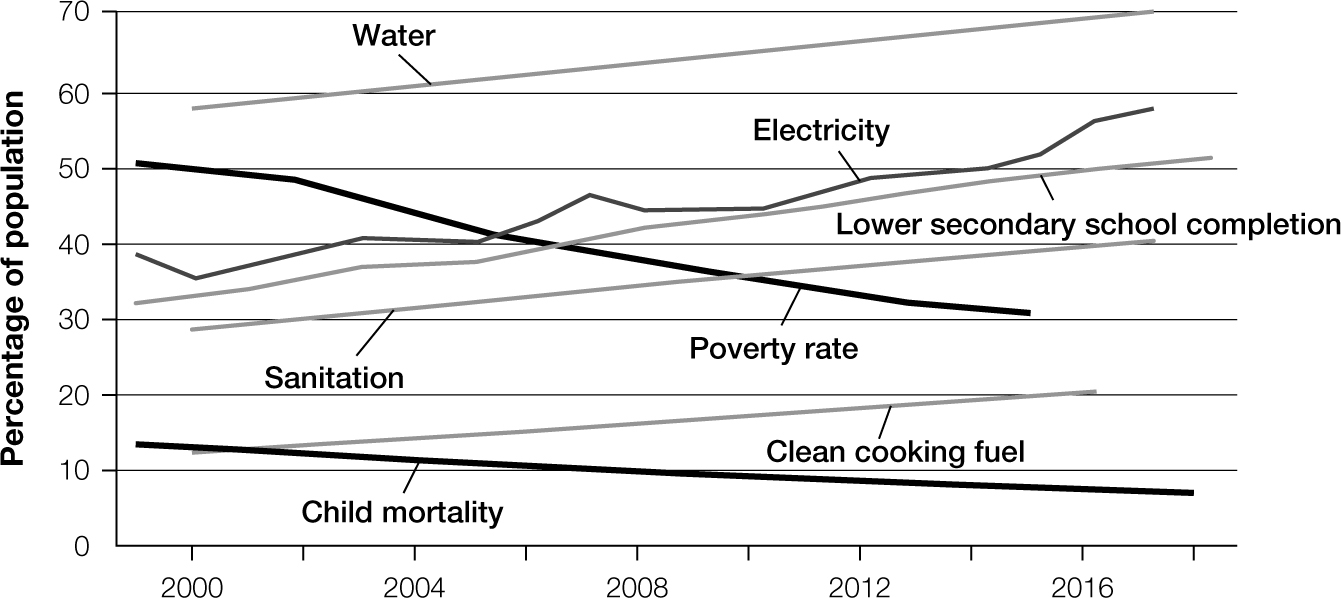

Despite reduced investment in public health and education in developed countries since the 2008 crisis, improvements are evident, especially in the developing world (figure 9-1). According to UNESCO, global literacy moved from 65 percent in 1975 to 86 percent in 2018.13 Child mortality has declined in most countries, and life expectancy has increased. There are places that, like the United States, have seen declines (and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] reports that “U.S. life expectancy continues to decline”), but the aggregate global picture is brighter, largely because of successful efforts of NGOs.14 As the next section discusses, some new problems in health and education have emerged as growing populations in developing countries move toward unplanned megacities with inferior infrastructure. In addition, fertility is declining in the wealthy nations.

FIGURE 9-1

Two decades of progress in the world’s poorest countries

Source: Donna Barne, “Two Decades of Progress in the World’s Poorest Countries,” World Bank Blogs, December 11, 2019, https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/chart-two-decades-progress-worlds-poorest-countries.

Note: Progress among lower-income countries receiving assistance from the World Bank’s International Development Association. The graph shows the percentage of the population that has access to at least basic drinking water, basic sanitation, clean cooking fuel, and electricity; percentages of relevant age groups completing lower secondary school and people living in extreme poverty; and mortality rate of children under age five. The declining black lines and rising gray lines both indicate progress.

The Rise of State Capitalism

As a source of disruption in the last decade, the rise of state capitalism has primarily resulted from the shift in leadership and policy in China. As long as China appeared to be moving its institutional arrangements for governance toward alignment with the nations of the West, the frictions between countries practicing market capitalism and those practicing state capitalism were accepted as a price of progress. The petrostates, including Russia, were always understood to be managed at the state level, but except when their moves as a cartel had political objectives and especially large impacts, they were usually perceived as manageable actors in the global market.

Because of China’s combination of economic size, centralized control, and newfound inclination to assert itself internationally, the country under Xi Jinping has proved to be a very different matter. On the basis of purchasing-power parity, China’s GDP passed that of the United States in 2014.15 This change in status has meant that China’s moves to achieve national objectives through the market system by nonprice methods such as state funding have been perceived as threatening to many countries, including the United States.16

Radical Movements, Terrorism, and War

The past decade has certainly seen no abatement of radical movements, terrorism, or war. In the Middle East, the withdrawal of the United States from Iraq led to the rise of ISIS and its spread across the Levant and into Africa. In Syria, the response of Assad’s government to protesters fleeing drought led to civil war and the emergence of a radical Islamist state in Eastern Syria. The Arab Spring led to several revolts that were crushed. Libya collapsed in civil war. There is ongoing warfare in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The war in Afghanistan continues. India has moved troops into Kashmir. The Buddhists of Myanmar engaged in ethnic cleansing, ejecting the Muslim Rohingya. China has moved to reeducate its Muslims. Violence as a means to further state (and organized nonstate) ends has been commonplace.

Pandemics

Pandemics have continued and perhaps increased. To some extent, their increased threat is a consequence of other factors such as global travel and weak governance. Medical historians tell us that new diseases have always crossed over from animals or other vectors as the movements of vectors and humans brought people into contact with sources of disease. In recent times, governments have invested in capabilities and cooperated reasonably well to catch these new threats early, isolate them, and sometimes eliminate them. But efforts have not always been so successful. For example, Ebola moved out of the rural areas to which it had generally been confined, invaded several major cities, and even appeared for the first time in Europe and the United States. A review of World Health Organization data suggests that except for malaria, the toll of epidemics is increasing, with opioid abuse in the United States providing a significant new threat.17 As of early March 2020, a novel coronavirus had claimed over 8,000 lives globally, and infections had been confirmed in 145 countries. It was unclear when and how the pandemic would end.

Inadequate Institutions

In the first edition of this book, in addition to the ten disruptors described, we proposed a possible eleventh. The feckless behavior of governments in many countries as they ignored the ten disruptors leads us to add that possible disruptor to our list. Many executives in our forums said that national governments lacked the economic strength and political will to deal with the disruptors and that our international institutions were not designed with the disruptors in mind. Unfortunately, the past decade has provided more evidence that the executives were prescient. If anything, governments have acted in ways that have aggravated the disruptors, for example, the U.S. tax cut and the strong reaction against migrants in several countries. The U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on climate change has highlighted the difficulty of forging effective multilateral institutions to address the disruptors at a global level. Similarly, the unilateral abandonment of the Iran nuclear deal by the United States has fueled tensions in the Persian Gulf. These tensions have recently threatened to boil over and have made multilateral international agreements seem more unstable and less likely to be formed in the first place.

Interactions Among the Disruptors

This list of challenges makes for depressing reading. One might have hoped that problems recognized in 2007 would have been dealt with in the years that followed. With partial exceptions like public health and education, that did not happen.

Instead, the decade has produced new threats such as those arising from digital technologies and has seen systematic interactions of many disruptors. Chapter 4 made this point theoretically. There, we described market capitalism as embedded in a context of interrelated forces and arrangements that we called its preconditions, and we discussed how the forces can reinforce or undermine one another. The past decade has revealed the complexity of some of the interactions. We now examine how the disruptors have interacted to create problems that are more complex and that further amplify the threat to market capitalism.

Interrelationships Among Migration, Environmental Changes, Public Health, and Education

Although environmental degradation was not seen as the most immediate threat to market capitalism in our earlier research, business leaders considered it an existential problem. During the past decade, rising temperatures, violent storms, sea surge, and drought have damaged agriculture, flooded cities in both the developed and the developing world, limited the availability of drinking water in major cities, generated unprecedented landscape-scale wildfires, and led to migration and crises in public health in many locales.

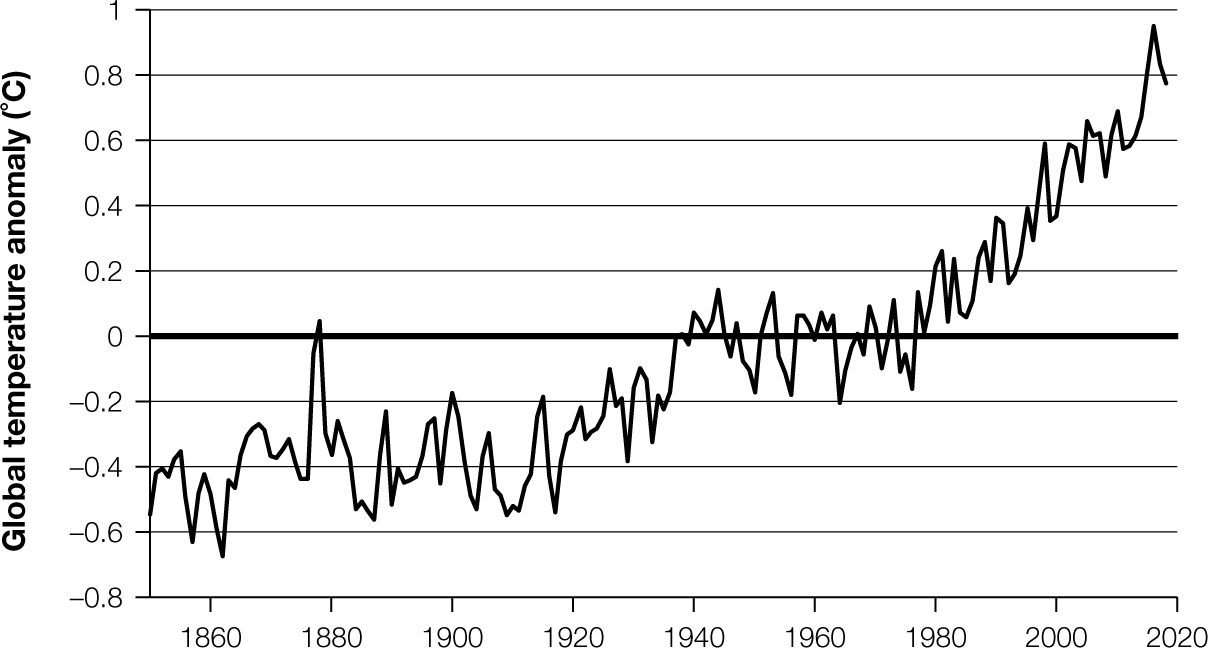

Figure 9-2 shows the steady rise in the average temperature all over the planet. The impact of global warming is particularly strong in regions where economic activity, especially agriculture, depends on the availability of water. In the United States, the Colorado River is no longer a completely reliable source of water; the snowpack varies over the years. The U.S. Midwest and Southwest experience more frequent droughts, and the major aquifers in these areas are declining. In Europe, dense populations and warmer climates have led to drought and have stressed aquifers from the Atlantic across into Asia all the way to the Pacific between the northern fortieth and fiftieth latitudes. The Middle East is also stressed. In Africa, the Sahara is expanding southward. India is facing severe challenges as the monsoon season becomes more irregular. Further south, Latin America and Australia have experienced increasing drought.

FIGURE 9-2

Global average temperature anomalies, 1850–2018

Source: Our World in Data, “Average Temperature Anomaly, Global,” Global Change Data Lab, accessed September 17, 2019, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/temperature-anomaly. Data from C. P. Morice, J. J. Kennedy, N. A. Rayner, and P. D. Jones, “Quantifying Uncertainties in Global and Regional Temperature Change Using an Ensemble of Observational Estimates: The HadCRUT4 Dataset,” Journal of Geophysical Research 117 (2012), D08101, doi:10.1029/2011JD017187.

Note: Land data prepared by Berkeley Earth and combined with ocean data adapted from the U.K. Hadley Centre. Global temperature anomalies relative to 1951–1980 average.

Over the past decade, the challenge posed by climate change in the form of drought and flooding amplifies problems of migration, generally from agricultural regions toward cities and from lower to higher land. Across the globe, the Middle East, regions north of the equator in Africa, and areas of Central Asia from the Black Sea to Mongolia and Vladivostok are experiencing more frequent and persistent drought.

A drought in northeast Syria can be thought of as the trigger event for the start of the Syrian civil war.18 People from the region moved south seeking sustenance. Since Syria was a national socialist state, the migrants turned to the government for support. When it was not forthcoming, they protested, and when, instead of receiving help from the government, the protesters were shot at (or worse), some Syrians went to war. More than a decade later, hundreds of thousands have died, and millions have migrated.

This brief summary of the situation in Syria provides a dramatic example of how the disruptors can interact. To begin with, the drought led to internal migration to cities.19 As often happens, the migrants then faced unemployment and economic stress. When they protested the government’s failure to provide assistance, the autocratic Assad government responded violently to the protest. The state’s violent response led to civil war, further severe internal displacement, and international migration. In Western Europe, the international flow then exacerbated political problems that arose from the unresolved economic problems triggered by the 2008 financial crisis.

The dynamic of drought-driven migration is not unique to the Middle East. Water scarcity has spurred migration in North Africa, Central Asia, and parts of China. In China, the migration is internal, but the scale of movement is large. On a global basis, observers expect that the exodus from rural areas to urban regions will add two billion city dwellers.20

This urban growth in developing countries has led to the phenomenon of poor megacities. Paradoxically, the problem lies partly in the general improvement in public health. Child mortality has dropped dramatically (figure 9-3), and primary education has improved.

FIGURE 9-3

Child mortality by income level of country

Source: Max Roser, Hannah Ritchie, and Bernadeta Dadonaite, “Child Mortality and Income Level of Country,” in Child & Infant Mortality (Our World in Data, 2013; updated November 2019), https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality#child-mortality-and-income-level.

These patterns are not unlike what happened in Europe and the United States during nineteenth-century industrialization. But in those cases, cities such as London and New York, which were dark, crowded, and infested with disease, drew on their new wealth to begin building sewers and water systems and dramatically improving public health. With improved health came falling child mortality and growing populations. Government efforts to clean up the cities were matched by improved public education, producing a healthy and educated population and a strong labor force for the growing industry. The labor force, in turn, fueled the consumption that drove economic growth.

In the developing world, however, the improvement in health is associated with successful efforts by NGOs to eradicate infectious disease, particularly childhood diseases. The megacities of Africa and Southeast Asia thus experience growing populations but lack an improved government or a growing industry.21 Water, sewers, and employment are all deficient or absent. Moreover, where there is industrial growth in fields such as apparel and light industry, the export markets are crowded with products from competitors, including the Asian Tigers (and domestic firms in developed markets).22

Interestingly, well before China’s emergence as an economic powerhouse, its so-called barefoot doctors (rural health-care providers with often-minimal formal medical training) brought hygiene to most of its population. Education was also supported. By the 1980s, when industry was unleashed under Deng Xiaoping, a healthy, educated workforce was available to serve its needs. At different times in history, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and Vietnam have provided other examples of the same phenomenon—workers with improving health ready to serve industry in a country with stronger governance. It is the absence of such efforts that burdens various nations in Africa, South and Central America, and South Asia.23

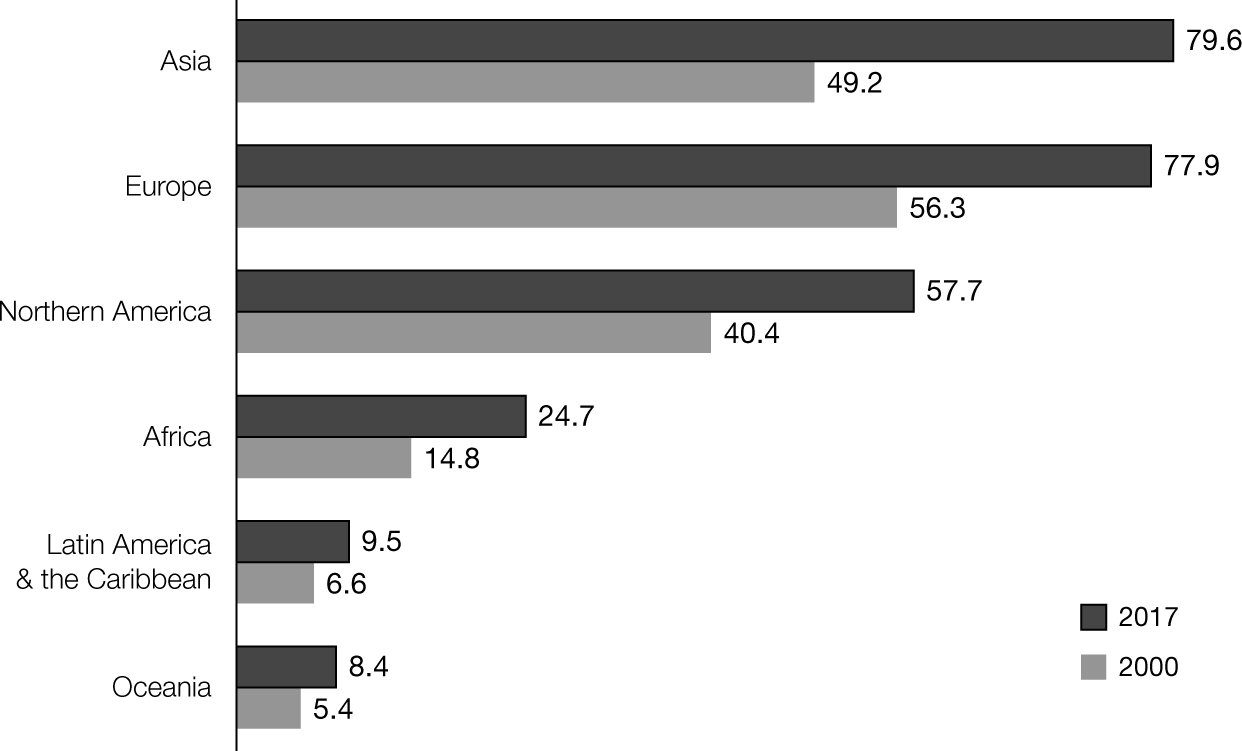

The exports of China, Taiwan, South Korea, and Thailand, together with protectionism by Western governments responding to postcrisis pressures on their workers, have made it very difficult for producers in emerging markets such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nigeria to drive economic growth with exports. Where governments are weak, the problems are compounded. Consequently, instead of fueling economic growth, the growing urban population drives emigration (figures 9-4 and 9-5).

Number of international migrants (millions) by region of destination, 2000 and 2017

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, “International Migration Report 2017,” United Nations, 2017, www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2017_Highlights.pdf.

FIGURE 9-5

Immigrants as a percentage of population

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, “World Population Prospects: 2017 Revision,” United Nations, 2017, https://population.un.org/wpp/.

As noted in chapter 2, the World Bank has estimated that perhaps more than 80 percent of the world’s workers in 2030 will be unskilled and live in developing countries. If this projection turns out to be accurate, the scale of the unemployment, health, and social problems outlined above will be enormous.

Returning to the environment, while drought and lower child mortality drive unmanaged growth in the megacities, flooding has created other problems as higher storm surges and rising sea level endanger coastal cities like Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Lagos, Nigeria. Sea-level rise in Dhaka is already driving people south toward the state of Assam in India, where a nationalist government is attacking the non-Hindu Muslim population. The risk of damage from sea-level rise is no less acute in developed nations. Climate Nexus reports that

climate change has already contributed about 8 inches (0.19 meters) to global sea level rise, and this has dramatically amplified the impact of cyclones and other storms by increasing baseline elevations for waves and storm surge. A small vertical increase in sea level can translate into a very large increase in horizontal reach by storm surge depending upon local topography. For example, sea level rise extended the reach of Hurricane Sandy by 27 square miles, affecting 83,000 additional individuals living in New Jersey and New York City and adding over $2 billion in storm damage.24

In sum, environmental and demographic changes have interacted to generate powerful forces, some of which will need a response from the governments of nation-states in the form of infrastructure, education, and public health. At the same time, however, the governance of nations is stressed by economic and political forces generated by the trade and finance systems and their impact on the distribution of the GDP of nations and among their citizens.

Interactions Among Inequality, Trade, and Finance

Of more immediate concern to our executive panels in 2007 and 2008 was income inequality, which they universally linked to the threat of populist, protectionist governments. By 2019, we had witnessed many of the problems that the business leaders had anticipated. The recovery from the financial crisis has been associated with a continuation of the increase in inequality of income and wealth within many countries, but also across regions, while in other countries the gap has narrowed. Speaking generally, OECD countries have done poorly, with some recovering better in recent years.

The picture has a great deal to do with the situation before the crisis and the way its aftermath was managed on a country-by-country basis. In the United States, for example, the economy recovered steadily, but the benefits were captured almost exclusively by the top earners.

The latest numbers from the Congressional Budget Office show the vast gap between income even after transfers and taxes in 2013 that were designed to ameliorate the problem (figure 9-6). In the period from 2009 to 2010 in the United States, 93 percent of the recovery in real income was captured by the wealthiest 1 percent of households. Similar discrepancies appeared in other parts of the developed world. Why? The answer lies in part with conditions before the crisis and in part with how the crisis was resolved.

FIGURE 9-6

Distribution of income before and after federal transfers and taxes, 2016

Source: Chad Stone, Danilo Trisi, Arloc Sherman, and Jennifer Beltran, A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality (Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 13, 2020), https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/a-guide-to-statistics-on-historical-trends-in-income-inequality, accessed January 29, 2020.

Note: Figures do not add to 100 due to rounding.

Since the oil shock of 1973, earnings of the lower-income part of the U.S. population have increased slowly. Driven by large rises in the price of energy and metals and the hypercompetition in the markets for manufactured goods, the contribution of labor to manufacturing value added declined significantly, while the cost of materials and energy increased. Labor’s contribution to nonfarm business income declined from 66 percent in 1972 to 56 percent in 2012.25 (In effect, the relative value of labor and materials changed—with the terms of trade shifting against the income-earning potential of lower-skilled workers.) Increases in exports of higher-value goods from Japan and, later, Taiwan and South Korea to developed markets in the United States and Europe meant that prices for cars and other consumer durables were under constant pressure. The high quality of these imports also put pressure on U.S. and other Western manufacturers. Their response was often to move sourcing to East Asia. Retailers exacerbated this challenge by moving their sourcing overseas.26

For workers in the United States and other Western countries, unemployment and stagnant wages resulted. Later, in the 1990s and early 2000s, the digital revolution put further pressure on wages as some service jobs were replaced with various forms of automated operations.27 Figure 9-7 shows that real wages for middle- and low-income U.S. workers barely moved between the 1978 oil crisis and 2018.

FIGURE 9-7

Real wage trends in the United States between 1979 and 2018

Source: Adapted from Congressional Research Service, “Real Wage Trends, 1979 to 2018,” updated July 23, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R45090.pdf.

Note: Shaded vertical bars represent periods of recession.

The global economy also saw a dramatic increase in liquidity as the earnings of the petrostates and the savings from the East Asian tigers (Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore) flooded the financial system, driving down interest rates.28 At the same time, the cost of services such as health care and higher education increased, further squeezing the lower and middle classes of the developed countries, especially those without universal education and health services, and people on fixed incomes.29 To maintain their consumption spending, workers in the United States turned to the value of their homes. The increased liquidity and low interest rates meant that the value of their houses increased, permitting further borrowing. The early 2000s saw a combination of further financial deregulation and the development of financial derivatives that made it easier for the financial system to securitize and thereby increase the availability of mortgages to low-income borrowers. This borrowing enabled low-income homeowners to maintain their spending—while piling up large amounts of debt.30

In much of Europe, the same forces of Asian imports and automation affected the economies, but in those countries, it was governments that borrowed to support the safety net that provided the standard of living of their populations.31 Outliers to this pattern were Spain and Ireland, where a real estate boom played out much as it did in the United States.

The only exceptions to excessive borrowing by either the government or individuals were Germany and the Nordic countries. There, strong education and business-friendly local policies supported successful export-driven economies. The crisis of 2008 had large impacts on their banks, but their populations were much less affected than those in other European countries.

When the crisis arrived, the economies of Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal were hit hard, as their ability to finance their governments’ debt was impaired. In turn, that debt sat on the balance sheets of the German and French banks that had helped finance their companies’ exports to the Southern European countries. France and Germany used their influence in the European Union to have the European Central Bank buy the debt from their banks, effectively Europeanizing the debt. But even by late 2019, not all the underlying company debt had been written off, and this debt was weakening the ability of the European banks to finance new growth.32

In the United States and other parts of the developed world, governments intervened with regulation after the collapse; the aim was to force banks to strengthen their balance sheets. These governments also used central bank funds to shore up their banks so that these institutions could continue to function.

But the efforts to support the banks provided little in the way of relief to the borrowers. The U.S. government did force banks to recognize and write off their bad debts and supported this effort by buying up bad debt. But the generation of borrowers who funded their expenses with loans on their homes saw their wealth erode as the housing price bubble that had been fueled by subprime mortgage availability collapsed. Many borrowers declared personal bankruptcy or walked away from homes that were underwater (i.e., mortgages higher than the house value). The limited assets that many of these families had managed to build up—largely through homeownership and appreciation in house values—had in effect disappeared. At the same time, companies that had retrenched to solidify their balance sheets laid off workers and froze or cut wages. To the extent that Congress would permit, fiscal policy was also used to support the economy, especially the auto industry and its suppliers. By and large, lower- and middle-income Americans were left out as the macroeconomy began the recovery, which has now continued for ten years (table 9-1).33

TABLE 9-1

Real income growth by groups (in percentages)

Source: Emmanuel Saez, “Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States,” University of California, Berkeley, Department of Economics, January 25, 2015. This is an updated version of “Striking It Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States,” Pathways: A Magazine on Poverty, Inequality, and Social Policy (Winter 2008): 6–7. Based on previous work with Thomas Piketty. Reprinted by permission.

Note: Computations are based on family market income, including realized capital gains before individual taxes. Incomes exclude government transfers, such as unemployment insurance and Social Security, and nontaxable fringe benefits. Incomes are deflated using the Consumer Price Index.

a. The fraction of total real family income growth (or loss) captured by the top 1 percent. For example, from 2002 to 2007, average real family incomes grew by 16 percent, but 65 percent of that growth accrued to the top 1 percent, while only 35 percent accrued to the bottom 99 percent of U.S. families.

In Europe, governments imposed various degrees of austerity to restore country balance sheets, but the effect was self-defeating because their economies were slowed by the cuts in spending. The result of such policies in the United Kingdom was particularly strong in the manufacturing and agricultural parts of the country—precisely the areas that would later vote for Brexit.34 In Germany, the government has run surpluses even while the economy has experienced negligible growth.

By 2020, banks were still funding their lending and investment with short-term capital, and in many countries, they have failed to address the nonperforming loans on their books since 2008. Central bank balance sheets are heavy with debt, and interest rates remain at low—even negative—levels associated with stimulus policies. Income for savers has been limited. Perhaps more worrisome, layered tranches of collateralized loan obligations in the United States are emerging as the new derivatives providing more than $1 trillion dollars of opaque leverage to the system. There is again considerable concern that a new collapse is possible.35

The political response to slow growth or no growth in household income has been nationalistic, even nativist. Those hurt by these crises have turned on the immigrants arriving in their countries from the Middle East and Africa. Even immigrants from Eastern Europe have experienced resentment as they used their skills to take decent paying jobs. The “Polish plumber” became an object of derision in the United Kingdom. On the continent, Muslims were attacked in the same way that Donald Trump had condemned Muslims and Mexicans in the United States.

The seeds of populist antipathy to immigration in the United States have deep roots, dating back to its earliest years as a country. After early and mid-20th century limits on immigration were eased off starting in the 1960s, the U.S. government began implementing increased control of immigration under the Clinton administration. Immigration rose steadily under all later administrations, as did deportations, until they peaked in 2013. The global problem has political consequences that reverberate through all administrations.36

Undeniably, the problems in developing countries are driving emigration, and the electorates in developed nations are resisting these flows in much the same way that immigration was resisted in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century. What is new is that the slow growth in the developed nations and the level of economic competition from developing nations has generated a populist and often nationalist response that (among many other problems that it may generate) is disruptive to trade arrangements.

Trade flows have become increasingly complex. What used to be a simple transaction in which goods from one country were moved to another, much as the eighteenth-century economist David Ricardo would have understood, has been transformed into a global network of sourcing decisions.37 Something as simple as a woman’s outfit might be assembled from factories in several countries. A case study of Liz Claiborne, written in 2001, provides an example:

The Liz Claiborne strategy made sourcing especially demanding. Because the divisions produced coordinated wardrobes, individual items that were assigned to particular factories—the suit top in China, the bottom in Guatemala, and the blouse in Thailand—had to arrive in the market at the same time matching perfectly—and satisfying US trade legislation in the form of quotas allocated to particular countries. The strategy for managing these demands [was] captured by what Bob Zane described as the “7 C’s”: Configuration, Consolidation, Certification, Concern, Collaboration, Coalition, and Cost.38

Similar complex chains existed in major consumer durables such as cars. In its July 2019 story on trade, the Economist reported that “Mexico’s car exports to Germany have nearly 40 percent German components by value, while those crossing its northern border have over 70 percent American content.”39 An iPhone made in China would include a chip with U.S. intellectual property, U.S. design, and possibly U.S. hardware, and hence its product value would be substantially from the United States. The fight over 5G (fifth-generation) phones is partially a contest over whether that pattern will continue or whether a Chinese firm, Huawei, will capture global markets with a 100 percent Chinese product.

The observed trends may have multiple sources and might not simply reflect a trade war. The OECD has reported that trade growth has fallen from 5.5 percent in 2017 to 2.1 percent in 2019.40 Some of this decline undoubtedly reflects protectionism as tariffs have cut U.S. exports of soybeans and European exports of steel. But independent of protectionism, multinational companies have been adjusting their supply chains for higher-value goods.

On the one hand, labor costs in China have risen, while new approaches to merchandising that emphasize customization and speed have led multinational corporations to move manufacturing closer to their markets. On the other hand, sellers of labor-intensive goods such as footwear continue to move sourcing to wherever wages are lowest and quality is adequate. For example, in the most recent years, footwear manufacturing has bloomed in Ethiopia. Low-end apparel has moved to Bangladesh, but labor practices—such as those leading to the Rana Plaza collapse in 2013—and poor quality continue to pose problems for manufacturers and retailers based in developed countries.

The complexity of trade and its evolution is described in a major study by the McKinsey Global Institute. The study divides trade into six archetypes of value chains, each type with its own distinct pattern of factor inputs, trade intensity, and country participation: global innovations, labor-intensive goods, regional processing, resource-intensive goods, labor-intensive services, and knowledge-intensive services.41 The major characteristics of each archetype are different. Global innovations are concentrated in five advanced countries. The portion of labor-intensive goods traded globally is decreasing. Regional processing consisting mainly of heavy intermediate goods is not readily traded, while resource-intensive goods (agriculture, mining, metals, and energy) are geographically concentrated, employ a major portion of the global workforce, and fluctuate dramatically with global output. Labor-intensive services employ large numbers of unskilled workers and have low trade intensity, whereas knowledge-intensive services employ highly paid workers in highly traded outputs. The McKinsey study estimates that trade in knowledge-intensive services is undervalued by more than $4 trillion.

The report also notes that an important driver of many trends in trade is the shift in consumption toward China. Because of the country’s extraordinary economic growth, much of what is produced in China now stays in China.

An additional complexity has been created by China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). With funding from government sources, Chinese manufacturers are making major investments in Africa, the Near East, and key parts of Europe such as the Greek port of Piraeus to open markets for China that have not already been captured by the West. These investments potentially displace goods and services that might otherwise come from European or even U.S. sources.

Over the last decade, the consequences of these changes in trade have been reflected in the incomes of the nations around the world and their people. But the consequences are specific to geography and economic position. Those who finance the trade or own the successful producers thrive. The booming stock markets have provided historic opportunities for hedge funds to benefit from the growth. The periodic crises—especially the 2008 crash—tend to concentrate wealth. Those displaced or squeezed suffer flat or diminished incomes. These pressures have fueled the political debate about globalization. In retrospect, we could have appreciated the clear signs of the political tension in the Seattle anti–World Trade Organization riot of 1999. In other words, aggregate trade has moved upward with the growth of the global economy, but the changes brought on by trade have had such uneven impacts that the parties injured now constitute a major political force.

A critical question, therefore, is how nations manage those changes. Differences in nations’ systems of government have a great influence on the lives of their citizens.

Friction Between State Capitalism and Market Capitalism Aggravates Trade Tensions, Financial Instability, and Inequality

A decade ago, our panel of executives worried about potential collisions between state capitalism and market capitalism. They did not foresee China’s BRI—this development initiative was not announced until 2013—but it is a good example of how state capitalism has challenged the global market system.

Russia and China are the two most important examples of state capitalism. Although Russia is possessed of enormous raw material deposits, it is, from the perspective of this discussion, primarily a developer and exporter of oil and gas. Exports represent close to 20 percent of the economy, and these are primarily oil, gas, chemicals, and weapons. Nearly half of Russia’s exports, primarily energy, go to Europe. In a $1.6 trillion economy, Russia’s 2018 trade surplus of $100 billion, reflecting a significant recovery in oil prices, indicates the critical role that energy production currently plays in Russian economic and political life. The state energy company Gazprom dominates the energy sector. At various times, Russia has used the importance of its exports to Europe as a foreign-policy tool. In other respects, Russia is a relatively closed economy, with limited foreign investments coming into the country.

In the 1990s, with the breakup of the Soviet Union, Russia experienced considerable privatization. But beginning with Vladimir Putin’s first presidential term, from 2000 to 2008, the economy has been under the tutelage of the Kremlin. Private ownership remains, but significant companies follow the leadership of the government or risk ceasing to be private. As noted, Gazprom functions as part of the government.

In contrast, beginning in 1979, the Chinese economy experienced a dramatic opening and rapid growth. Foreign investment played a key role as China transformed itself from a supplier of low-cost manufacturers that depended on endless supplies of low-cost labor to a midlevel, developed economy producing globally competitive manufacturers of high-value-added goods such as high-quality garments, pianos, automobiles, locomotives, and electronics. The Chinese economy has two important sectors: private and state owned. The latter has played a critical role in a variety of key industries, such as agriculture, building materials, chemicals, electrical equipment, energy, metals, telecommunications, rail and air transportation, and much of banking. All state-owned enterprises (SOEs) belong to SASAC, the State Authority for Supervision, Administration and Control—a kind of superconglomerate. SASAC approves the strategies, finances, and top personnel appointments of its subsidiary companies. An impressive 119 of the companies in the Fortune Global 500 are Chinese (121 are American), and of these, perhaps 80 percent are state owned.42 The private sector has led the development of automobiles, fast-moving consumer goods (e.g., clothing and shoes), electronics, home appliances, venture finance, and retail—all these products often in partnership with foreign multinational companies.

The preceding description of private enterprises and SOEs is based on market-system distinctions. The line between state control and private control is far less clear in a state-run system like China’s. Because all land belongs to the state, many transactions require permits. Finance and foreign exchange are controlled by the government as well, and consequently the Chinese “private” sector is ultimately under government control. Despite this pervasive government presence, China was admitted to the World Trade Organization in 2001. Members believed that China’s apparatus of control would gradually be dismantled and that the country would move to resemble something like a market capitalistic country. Under the premiership of Deng Xiaoping and his immediate successors, this supposition seemed to be the case as a vibrant private sector played an increasingly important role in the economy. In the era of Xi Jinping, this direction appears to have changed. The government is constraining freedom of movement by private companies and is providing aggressive support for the SOEs—including the BRI. For example, the boards of directors of private companies above a certain size must include a member of the Communist Party of China. In contrast, financing for the dramatic international growth opportunities provided by BRI is available from government institutions.

To be sure, other countries have managed their growth using significant leadership, coordination, and finance from their government. Both Germany and Japan in the 1960s and 1970s used coordinated industrial, trade, fiscal, and monetary policy to manage export-driven growth. They were followed by South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Singapore. Other countries, such as Brazil, have done the same. We have not described these efforts as examples of state capitalism, because the relationship between private ownership and the state is governed—at least in principle—by more transparent arrangements that keep business and government more separate. Industrial policy rather than state ownership is used to seek government objectives.

The scale and aggressiveness of Russian SOEs in energy and Chinese SOEs in manufacturing have disrupted the smooth progress of market capitalism. The United States and Europe have focused on these challenges for years in their trade discussions. From this perspective, President Trump’s use of tariffs can be seen as only a modest shift in a long-standing and increasing tension between state-led systems and other countries’ systems. As discussed in chapter 3, state and market capitalism inevitably collide.

These collisions also play out in financial markets, where energy prices, currency exchange, and money flows affect the world’s markets. As noted earlier, Russian oil and gas have a profound impact on domestic and global markets, but the high domestic savings rate in China (45 percent of GDP), together with limited tools for private domestic investment, has contributed to the high liquidity in global markets—the savings spilled into the global system—which in turn has driven asset appreciation. The financial instability leading to the 2008 crisis originated in part in Chinese surpluses. But easy, cheap money has fueled the market for corporate control, short-termism, and other negative features of the modern economy. The complex reorganization of trade and the drive for growth among state-capitalist nations have deeply disrupted the functioning of global market capitalism.

The challenge lies in the incompatible premises of market capitalism and state capitalism. Market capitalism is based on the premise that, subject to rules such as national antitrust laws or the trading rules of the WTO, the economic outcomes of free intranational and international trade will yield the best results for all. In contrast, state capitalism holds that economic outcomes should be achieved through active management by the state. Much as a large conglomerate manages its divisions, the state directs its SOEs to act in ways that serve state goals. This conflict of premises makes it hard for the systems to coexist.

A further complexity associated with state capitalism has been the ability of SOEs to make deals with corrupt governments without fear of the legal sanctions that might be applied to private companies. In this way, SOEs have contributed to a decline in the rule of law.43

Interactions Between Corruption and Terrorism Strengthen Each Other and Weaken Governance

As noted earlier, our panels of business leaders doubted whether governments and international institutions had the political will and economic strength to address the disruptors they identified. The past decade has not made these problems simpler nor the governments stronger. The stasis the world observed as Britain has struggled with Brexit is an example of this weakness. As we observed in the new preface, the task of government and international institutions has certainly not been made easier by the emergence of digital technology. This new linkage between individuals, groups, companies, and nations—while marvelous at facilitating communication, commerce, education, and medicine—has proved extremely vulnerable to manipulation by corrupt governments, terrorist groups, and autocratic nation-states. At the same time, it has given these groups new weapons of mass disruption.

The scale of corruption is now staggering, but whether it has increased is hard to know.44 UN secretary-general António Guterres has estimated corruption as at least 5 percent of global GDP. Mark Wolfe, senior U.S. district judge, estimates that captured nation-states (states that are run by, and for the benefit of, a ruling clique or family) represent 10 percent of global GDP.45 British journalist Misha Glenny has estimated that organized crime (drugs, currency, trafficking, and other smuggling) constitutes 15 to 20 percent of all economic transactions worldwide.46 Obviously, calculating an accurate estimate of the burden of corruption is difficult, but the problem is enormous and seems to have worsened over the last decade. It poses a heavy tax on affected commerce, diverts revenues from governments into private hands, and provides a motive and funding for violence.

To the extent that corruption is a tax on commerce, it deprives governments of revenue that they might use to improve public health, education, or infrastructure. For example, Gabon is a geographically large nation blessed with oil and minerals. The GDP per capita is $8,300, but most of the population lives with incomes under $2,000 because of massive corruption.47

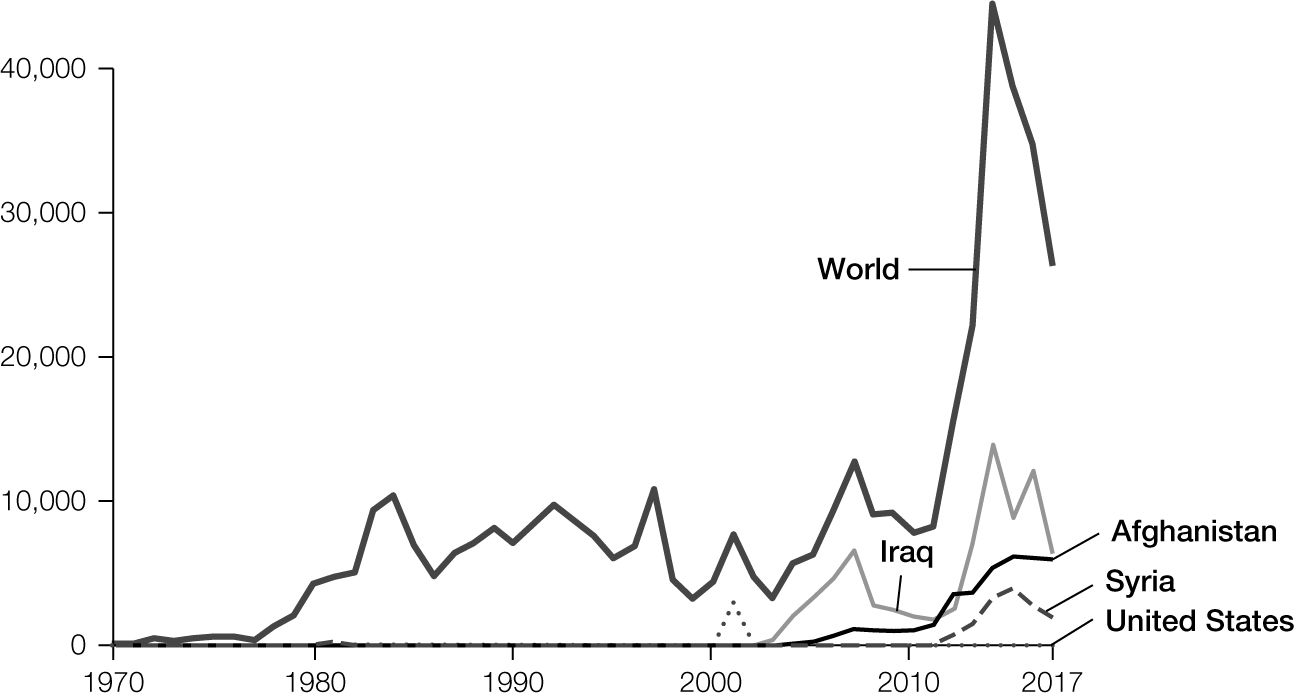

Wherever the state itself has become a corrupt enterprise, the impact on its population is devastating.48 Corrupt states can also easily become failed states. Afghanistan in the post-Soviet-invasion period is a good example. With government in the hands of warlords, corruption flourished. The Taliban set up home as a reform movement but funded itself through the opium trade. When Osama bin Laden fled Saudi Arabia, he established himself as Afghanistan’s guest. Al Qaeda has still not left. Whether Venezuela will become a home for terrorists is not yet clear, but the cabal that runs the state also runs the oil company and the black market and appears to deal extensively in drugs and other contraband. Emigrants from Venezuela to Colombia and Brazil have destabilized some of the remote regions of those countries. More generally, an analysis by corruption watchdog Transparency International shows that countries with higher levels of corruption also have weaker democratic institutions.49 Over the decade since we first wrote this book, terrorist attacks have continued to escalate (figure 9-8).

FIGURE 9-8

Number of fatalities from terrorist attacks

Source: Hannah Ritchie, Joe Hasell, Cameron Appel, and Max Roser, “Number of Fatalities from Terrorist Attacks,” in Terrorism (Our World in Data, July 2013; revised November 2019), https://ourworldindata.org/terrorism.

Note: Number of fatalities per year from terrorist attacks: total number of confirmed fatalities, including all victims and attackers who died as a direct result of the incident.

Both corruption and terrorism can be thought of as breakdowns in governance. The market system depends on a reliable system for secure ownership and transactions. These in turn require stable currency, reliable banking, honest officials, and safe trade, as well as free and fair courts to settle disputes. While the absence of systematic data makes it hard to assess trends, it is clear that the continued absence of these requisites in a variety of circumstances hinders business’s ability to function. More important to the argument of this book, the pervasiveness of corruption implies that business has a high stake in whether countries have effective governance. Business cannot treat countries like hotels that they check into (and out of) at their own convenience. If executives want a favorable environment for doing business, they need to support the institutions necessary to keep corruption and its consequences in check.

Failing governance has also contributed to the problem of pandemics. Pandemics result when deadly disease is allowed to proliferate in the absence of effective intervention by the institutions of public health. Infectious diseases continuously evolve, often in the crossover of pathogens from birds or other nonhuman animals to people, unremittingly confronting human immune systems with new threats. Disease transmission cannot be stopped; it is a feature of our being part of a natural system inhabited by countless other organisms. Since by definition our immune systems have little or no natural defense against recently evolved disease agents such as new viruses and bacteria, these agents can spread rapidly and have devastating effects in a human population. In the past, crossover might wipe out a small rural enclave but cause no larger problem. Today, however, even in remote regions, interactions associated with trade or war enable new diseases to spread more broadly and rapidly. When the diseases reach cities, the threat of contagion becomes much higher, and with air travel, a disease can move across the world quickly. The HIV/AIDS epidemic is an example of such a disaster. By contrast, SARS posed a similar risk but was quickly contained by public health officials when it emerged in 2003. The Zika outbreaks of the last decade have been similarly contained. In both the SARS and the Zika outbreaks, response by reasonably effective governance and national and international health organizations helped contain these emergent threats. The successful responses of these institutions show the importance of investment in, support for, and maintenance of these institutions. In early 2020, the coronavirus began sickening and killing people in China at exponentially rising rates. Reports suggest that the rapid spread is a consequence of government inaction in spite of courageous efforts by doctors and remarkable efforts by scientists.

When government institutions break down or are not allowed to function effectively, the consequences are frightening. The current threat from Ebola, which WHO deemed a public health emergency of international concern in July 2019, is exacerbated because it is taking place in the middle of the civil war in the Congo. The war in turn is fueled by a weak government and the lure of valuable minerals. As people flee the violence, they bring the disease with them. Poor education and limited public health help spread the disease as well. Some villages reject intervention, especially efforts to quarantine their relatives and bury the dead in ways determined by modern science to be safe. Migrants from the violence are reaching cities that lack a structure for tracking them. Again, this situation is an example of the stake that the business community has in effective government.

The point we are making here is not subtle. As argued in chapter 4, effective governance, including the rule of law, is fundamental to the functioning of market capitalism. Conflicts of any kind that undermine the rules by which transactions proceed and disputes are fairly resolved weaken the system. But they also weaken other aspects of society, such as public health. These aspects in turn are required for the successful functioning of the system.

Weak Governments and Outdated International Institutions

In our 2007 and 2008 discussions with global business leaders, many commented on weaknesses in the governmental context. As described in chapter 5, some executives thought that such weaknesses were inevitable because democratic governments would respond to misguided populist sentiment. Others thought the failings arose because the mechanisms of even the best governments were inadequate to the task of moving the world’s economies and polities through the difficulties identified in our discussions. None thought that post–World War II institutions such as the United Nations and the World Bank were capable of actions that would ameliorate the disruptors.

Part Two of this book examined these views and laid out our argument for business as a leader. Ten years later, our view can be expressed more emphatically: the problems facing the global market system are severe and appear to be worsening. Indeed, as we have discussed in this chapter, the disruptors appear to feed on and reinforce one another in ways that are creating ever-more-complex problems and putting market capitalism at even greater risk. There is no one comprehensive solution, and governments must be involved. But we stand by our earlier conclusion that business can and must play a role in addressing the disruptors—and can do so in ways that make strategic sense for business.

In earlier chapters, we have offered some examples of companies that were doing just that. In chapter 10, we examine several additional examples from work we have done since the book’s publication. These new illustrations again show that if companies bring their considerable capabilities to bear on these problems—often in collaboration with governments and NGOs—they can find creative ways to derive economic value and strengthen their business while also addressing the disruptors and helping build a more sustainable form of capitalism.

The challenge is to mobilize more companies to take on this essential work.