1

1

The sheer surprise of the Lindbergh nomination had activated an atavistic sense of being undefended that had more to do with Kishinev and the pogroms of 1903 than with New Jersey thirty-seven years later, and as a consequence, they had forgotten about Roosevelt’s appointment to the Supreme Court of Felix Frankfurter and his selection as Treasury secretary of Henry Morgenthau, and about the close presidential adviser, Bernard Baruch.

—PHILIP ROTH, The Plot Against America

“Pogrom”: The word’s origins can be traced to the Russian for “thunder” or “storm.” A dark remnant of the Old World, it retains the capacity to feel as immediate as yesterday’s outrage on morning services in Jerusalem: “The sight of Jews lying dead in a Jerusalem synagogue, their prayer-shawls and holy books drenched in pools of blood, might be drawn from the age of pogroms in Europe.”1

When a bird flies into a Lower East Side apartment in Bernard Malamud’s 1963 short story “The Jewbird,” its first words are, “Gevalt, a pogrom!” Mary McCarthy described the explosive response to Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem as a pogrom. In Annie Hall, Woody Allen has Alvy Singer insist that his grandmother would never have had time to knit anything like the tie worn by Annie (Diane Keaton), his non-Jewish lover, because “she was too busy being raped by Cossacks.” The quip is at once alert to its own crudeness and to its capacity to sum up an astonishingly sparse historical repertoire. Explaining why art impresario Bernard Berenson’s family abandoned Vilna (Vilnius today) for Boston in 1865, the author of a recently edited edition of the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper’s letters to Berenson writes that it was because they “were fugitives from anti-semitic pogroms”—despite the fact that the first pogrom wave erupted more than fifteen years later and even then, with rare exceptions, far away from Berenson’s native city. Irving Berlin recalled how in 1893 in his birthplace in Mogilev Province—“suddenly one day, the Cossacks rampaged in a pogrom . . . they simply burned it to the ground.” His family fled, smuggling themselves “creepingly from town to town . . . from sea to shining sea, until finally they reached their star: the Statue of Liberty.” Here as elsewhere, pogroms are shorthand for cataclysm, misery in a dark, abandoned place.2

For a readily accessible way to comprehend the diverse grab bag of such references, see Franz Kafka’s letters in the 1920s to Milena Jesenská; they speak of unease on Prague’s streets as a precursor to pogroms. The 1929 Hebron riot, Kristallnacht in 1938, and the anti-Jewish riots in 1941 Baghdad were similarly described. Arthur Koestler, in his novel of the late 1940s, Thieves in the Night, compares British Mandate officials in prestate Israel to pogromists: “I am a sincere admirer of Jews,” says one of them. “They are the most admirable salesmen of the world, regardless of whether they sell carpets, Marxism, psychoanalysis, or their own pogromed infants.” Pogroms were how Arab attacks against Jews in prestate Israel (and later) were often depicted; curiously enough, this was a source of solace, since such violence could thus be dismissed as artificial—the concoction of manipulative, reactionary Arab authorities.3

Pogroms continued to weigh heavily decades later in the deliberations of the Kahan Commission, which was chaired by the president of the Israeli Supreme Court. In those discussions, Israel’s behavior in 1982 during the Sabra-Shatila massacre in Lebanon was likened to that of malevolent Russian and Polish authorities during pogroms. In 1993 the New York mayoral candidate Rudolph Giuliani would accuse the city’s incumbent mayor, David Dinkins, of the same sins with regard to the Crown Heights riots: “One definition of a pogrom,” declared Giuliani, “is where the state doesn’t do enough to prevent it.” In the sixth season of Showtime’s Homeland, airing in 2017, the Israeli ambassador to the United States fears an Iranian nuclear bomb and asks pointedly, “Should we go back to the ghettos of Asia and Europe and wait for the next pogrom?”4

Sturdily portable, the term “pogrom,” like none other in the twentieth century, was believed to capture accurately centuries of Jewish vulnerability, the deep well of Jewish misery. And in stark contrast to the Holocaust, pogroms would never—despite their Russian origins—be tethered to a particular time, place, or dictator. In Malamud’s “The Jewbird,” once the bird opens its mouth and utters the word “pogrom,” the response from those in the Lower East Side apartment is, “It’s a talking bird. . . . In Jewish.”5 What else would a talking Jewish bird say if it were able to speak?

The word’s imprint was a by-product of the widespread, ever-escalating anti-Jewish violence in the last years of the Russian empire and the mayhem following the empire’s collapse. It was then that pogrom entered the world’s lexicon as one of the tiny cluster of Russian words—alongside tsar or vodka—no longer considered foreign. This trend solidified as anti-Jewish attacks crisscrossed Russia amid the 1905–6 constitutional crisis, in which eight hundred were killed (six hundred in Odessa alone). Such massacres were frequently the work of roving bands of Jew-haters, the so-called Black Hundreds, whose commitment to saving Russia from constitutional rule was translated into anti-Jewish brutality. The Yiddish author Lamed Shapiro described a son witnessing his mother’s rape: “Wildly disheveled gray hair. . . . Her teeth tightly clamped together and shut. They had thrown her onto the bed, across from me.”6

Once the empire finally crumbled in 1917, such attacks spiked amid the anarchy, banditry, famine, and ideological fervor of new, raw Bolshevik Russia. The dimensions of this savagery, involving Ukrainians and White Army Poles as well as Bolsheviks, have yet to be comprehensively calculated, since so much of the slaughter was registered only sporadically. Attacks on Jews now reached fever pitch, with Russia’s Bolshevik leaders seen by their foes as part of a Jewish conspiracy. It seems clear that no fewer than one hundred thousand Jews were murdered in these offhandedly brutal horrors, and at least that many girls and women raped and countless maimed between 1918 and 1920.7

Although pogroms would come to be seen as no less a fixture of the region than impassable winters or promiscuous drunkenness, until the early twentieth century the term was just one of several used for attacks of all sorts without specific linkage to violence against Jews. “Southern storms” would be how the riots of the early 1880s (largely in Russia’s southern regions) were spoken about; besporiaki, a generic word for “atrocities,” was still more commonplace. In the copiously detailed Correspondence Respecting the Treatment of Jews in Russia, issued in 1882 by the British Parliament on the massacres of the 1880s, atrocities are spoken of as “serious riots” or “disturbances,” with no mention at all of pogroms. (Responsibility for the riots, as described in that document, was placed entirely on the shoulders of Jews because of their allegedly oppressive commercial practices, their control over liquor, their usury, and their habitual radicalism.) When “pogrom” first appeared in newspapers in Europe or the United States—in the early years of the twentieth century—it was typically either defined or placed in italics. Jews were already familiar with it, of course, but it did not yet carry the incomparable burden it would soon take on. In Harold Frederic’s fierce exposé The New Exodus: A Study of Israel in Russia, published in 1892 and based on articles written by the New York Times London correspondent, the word “pogrom” never appears.8

This would soon change, something that occurred at the very moment when the wider world first took serious notice of the huge Russian Jewish community, then accounting for half the world’s Jewish population. Their migration westward since the 1880s or earlier, their concentration into dense, increasingly squalid urban clusters in New York, London, and elsewhere, their resultant poor hygiene, and their propensity for crime—all these, exaggerated or not, had been noted before, of course. But now, for the first time, the world’s attention turned resolutely to Russian Jewry and the discovery that there was no better way to understand the rhythms of that community than through the prism of pogroms. Synagogue prayer in the United States would begin to introduce hymns honoring a pogrom-ridden Russian Jewry, the first best-selling books about it in Western languages would be devoted to pogroms, and plays depicting the effects of such massacres would inundate the Yiddish- and English-language stages as far away as Australia.9

True, sympathy gave way in many quarters to mounting concerns in the wake of an unprecedented escalation in immigration, ever-shriller calls for restrictions, literacy tests, or other strategies to stem this deluge. The political radicalism increasingly associated with Jews struck fear or contempt in the hearts of many. This extraordinary visibility, however, was very recent. Until the first years of the twentieth century, Russia’s Jews were seen, if at all, in the West as mostly a dark, unfamiliar continent. “We are amazed,” wrote the literary historian Benjamin Harshav in 1993 in Language at a Time of Revolution, “at how wretched, degenerate, illiterate, or ugly our ancestors looked—only three or four generations ago.” Baedeker guides of the region as late as the first decade of the twentieth century offered no details regarding Jews in cities like Brody, just beyond Russia’s western border, where the vast majority was Jewish, except to say that they were loathed by the gentiles.10

Jews were clustered mostly in Russia’s western provinces, known in the English-speaking world as the Pale of Settlement and historic Poland, an area that stretched from a few hundred miles west of Moscow to the borders of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Romania. When they were thought of at all in Russia or abroad, it was mostly in terms of their economic proclivities—petty commerce, the making of cheap clothing, trade in liquor or grains—and their distinctive religious practices, which were considered mostly arcane, sometimes suspect. Their diet, language, and clothing, their secrecy despite their obvious volubility, and their many mysteries—perhaps, above all, their purported capacity to resist liquor’s allure—set them apart. They were often thought of as wealthy despite their ubiquitous poverty; they were seen as unnaturally adept at making money while excoriated as unnaturally susceptible to political radicalism. They were loathed for their unwillingness to be absorbed into the fabric of Russian life, though conversion did not necessarily rid them of the taint of Jewish origin. It was often assumed that public figures sympathetic to them had been bribed or otherwise strong-armed. It was commonplace for those so attacked—such as Prime Minister Sergei Witte, and later Rasputin—to be the target of accusations that they were paid off or were engaged in other nefarious activities.11

Since the mid-nineteenth century, Jews in large numbers had acquired a formal education, with Russia’s cities within the Pale of Settlement and elsewhere packed with university-trained Jewish doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, and notaries. Leon Pinsker, long the head of the Palestinophile movement, based in Odessa, was a beloved doctor and a cholera specialist who was eulogized at his 1891 funeral by more non-Jewish colleagues than by the Jewish nationalists whose organization he ran for nearly a decade. Russian-language books, not those in Yiddish or in Hebrew, were the ones most sought after in the many dozens of small-town libraries set up by Jews in the last decades of the nineteenth century. It was only once Hayyim Nahman Bialik’s brilliant Hebrew poem on the Kishinev pogrom, “In the City of Killing,” was translated into Russian—by Vladimir Jabotinsky, later the founder of right-wing revisionist Zionism—that it captured a widespread devoted following. Jews then emerged among the masters of Russian prose, with Isaac Babel and so many others beginning illustrious literary careers amid the twilight of imperial Russia.12

A startling example of Jewish integration can be seen in the infamous Mendel Beilis affair, in which a Kiev brick-factory manager was jailed despite no credible evidence, tortured, and eventually put on trial in 1913, charged with having killed a Christian boy for Jewish ritual purposes. The prelude to the trial—Beilis was first jailed in 1911—pitted many of the regime’s most vocal antisemites (who insisted that the whole endeavor was a farce) against a motley crew of fanatics who failed, in the end, to convict Beilis. The accused himself was absurdly miscast: Largely indifferent to Jewish ritual, he had served without complaint in the Russian army, befriended Russian neighbors who testified on his behalf at the trial, and made good friends of gentile prisoners he met in jail. Once declared not guilty (though the jury insisted that a ritual murder had taken place but not at Beilis’s hands), he became something of a local celebrity, his fame so great after his exoneration that tram conductors would as a matter of course call out, “Take number 16 to Beilis.”13

Nonetheless, even on the cusp of the twentieth century, Jews would continue to be widely viewed as they had been many decades before. Little less resonant than earlier were images comparable to those aired in the privately printed traveler’s book by the Englishman John Moore, A Journey from London to Odessa. In the summer of 1823, on an unnamed diplomatic mission, Moore kept a record of his trip through East Galicia with its “dirty, busy” towns “full of plunderers”—which was his description of Brody. “On looking over my journal, I find the following memorandum: . . . first litter, Jew, or Devil, fleas, etc. etc.” Here and elsewhere: “Their costume, features—movements—all produce a singular effect . . . as I walked out amongst them . . . and observed their grave, yet anxious countenances.” Time and again, he was struck by the uncanny energy of these dark figures: “Several lank Jews, in their black gowns . . . flitting about, making divers energetic appeals to me, and jarring with each other—enforcing their arguments by almost frantic gestures.” Still, no matter how much money Moore offered his wagon driver, the latter refused to travel on the Sabbath. The wagoner’s devotion to family life was no less admirable. His leave-taking outside his “mean habitation” was done without “parade—not acting. The marks of mutual affection were unequivocal.”14 Moore took in synagogue services, which he found hauntingly moving. Still, most Jews were intolerable:

No sooner had I arrived at [an inn] than a host of Jews entered my apartment, with all sorts of goods for sale. The weather was exceedingly sultry, and the odour of the exhalations from the filthy persons . . . was almost insupportable. I was obliged to call in the aid of the facteur [porter] of my hotel who by persuasions, threats and something approaching to blows succeeded at length in clearing the room.15

Against this complex backdrop, pogroms would come to be seen as the most transparent of ways in which to describe the condition of Russian Jewry. Proof of the term’s relative obscurity soon before it became commonplace may be seen in a London Times column appearing in December 1903. The piece opens by acknowledging that confusion probably exists as to what “pogrom” means, thus requiring a definition that distinguishes pogroms from mere massacres. It is then explained that pogroms come with the following features—these “well-established and characteristic rules.”16 They begin with rumors, hints that Jews soon will be punished with authorities looking the other way. Such rumors will surface a few months before Easter, with anti-Jewish propaganda circulated in taverns or cheap restaurants. Nearly always stoking the fire are accusations of deplorable Jewish economic practices or their dreadful killing of Christian children for ritual purposes.

Easter arrives amid this ever-toxic atmosphere, in which the smallest mishap can readily precipitate an explosion. This could be a fistfight between a Jewish carousel owner and a customer, which might lead at first to seemingly aimless mischief, perhaps boys tossing stones at Jewish buildings. Police then arrest a few of them but show little initiative to do much more. Now rioters have the signal they have been waiting for, prompting them to roam freely and go on the attack. Jewish houses are broken into, furniture is smashed, belongings are carried away, and plundered streets are strewn with feathers: “The Jews are very great consumers of poultry, and they carefully keep their feathers.”17 Once the authorities finally intervene, only on the morning of the third day, fear of any reprisal has evaporated, and rape and murder are now commonplace. All this, “from the very first pebble thrown by a small boy to the last murder committed, . . . is absolutely under the control of the Government.” These details—the fight with the carousel owner, the riot starting with the pelting of rocks by children, the feather-strewn streets, the rumors of ritual murder—were all drawn from newspaper reports of the Kishinev pogrom of 1903. It was this tragedy that, as the Times column put it, ushered in the start of pogroms as “a national institution—not a massacre in the ordinary sense of the term.”18

“Before Kristallnacht there was Kishinev,” as the journalist Peter Steinfels observed in 1998 in the New York Times. “A finger of God” is how contemporaries would refer to it; “an earthquake,” in the words of the Israeli historian Anita Shapira. “Kishinev” almost instantly became shorthand for barbarism, for behavior akin to the worst medieval atrocities.19

No Jewish event of the time would be as extensively documented. None in Russian Jewish life would leave a comparable imprint. The young Joseph Hayyim Brenner, the closest counterpart in Hebrew literature to Fyodor Dostoevsky, wrote in a letter of September 1903: “In the world there is certainly news. Kishinev! If we were to stand and scream all our days and our nights, it would not suffice.” Kishinev managed to push the Dreyfus Affair to the margins, and it dominated the headlines of American newspapers for weeks. The Jewish press would lead with it for months: “We write and write about Kishinev,” opened an editorial in Forverts (the Yiddish Daily Forward) in early May, “we talk and talk about it.”20

Moreover, it would become the only significant event embraced by all political sectors of the severely fractured Russian Jewish scene. And yet, like so many politicized lessons, these were as often as not the products of half-truths and untruths, of mythologies morphed into certainties, and of forgeries stitched together in the pogrom’s wake. And more than a century later many of these continue still, as we will see, to instruct generations of Jews and others regarding the essential condition of Jewish life in the past and present.

Pogroms would thus enter the lexicon of Jewish life as little less than a contemporary analogue to Egypt’s biblical plagues, the dark before the most momentous of modern-day Jewish exoduses. This occurred against the backdrop of the certainty—long suspected and finally buttressed with what now appeared to be incontrovertible proof—of government complicity. The knowledge that Russia’s officials fomented these attacks would prove decisive in consolidating long-standing Jewish political inclinations—most pronouncedly the marriage of Jews and the Left. Much else would, to be sure, cement this relationship, including the allure of revolutionary Russia, worldwide depression, and the rise of fascism, but no ingredient proved more formative than the commonplace that Europe’s most conservative empire unleashed hoodlums to beat, rape, and kill Jews.

Pogroms would provide the stuffing for lessons as diverse as distrust of conservatism, the urgency of radicalism (eventually liberalism, too), the return to Zion, territorialism, and, arguably, the fight for black civil rights. Kishinev would also be built squarely into the history of prestate Israel’s defense forces, and it would inspire the call for assimilation into the democracies of the world so different from autocratic Russia. This was foregrounded most resolutely in Israel Zangwill’s much-celebrated 1908 play, The Melting Pot, which its Anglo-Jewish author insisted was “the biggest Broadway hit—ever.” Its protagonist, a brilliant, tortured violinist unable to rid himself of recollections of Kishinev’s brutality, struggles with whether the best response to these demons is the use of a gun or a violin. Choosing the latter at the play’s end, he muses, “I must get a new string.” Indeed, so must all Jews, as Zangwill’s play teaches, with the New World beckoning and Russia forever damned.21

Amid a cacophony of outrage, instant relief projects, and protest meetings in more than a dozen countries (with some two hundred such gatherings in the United States), Kishinev’s pogrom became a stand-in for evil, a jarring glimpse of what the new century might well hold in store. “I have never in my experience known of a more immediate or a deeper expression of sympathy,” President Theodore Roosevelt declared at the time.22

Chronology explains some of its resonance, the shock that such “medieval-like butchery”—these terms were repeatedly recycled at the time—had intruded on the dawn of the new century. The explosion in worldwide communications networks—in particular, the proliferation in the United States of the William Randolph Hearst press empire, which embraced Kishinev as a cause célèbre while highlighting it with the lavish use of photography—further contributed toward setting it apart. That all the slaughtered could be captured in a single widely reprinted photograph—with the forty-five shrouded Jewish dead stretched out on the floor of the local Jewish hospital—went a considerable distance toward consolidating this as a tragedy unlike any other.23

And then there was the role of ideology: The pogrom occurred at a moment of singular coherence, of overall popularity for Jewish political movements, including the Jewish Socialist Labor Bund, the Zionists, and many others. Kishinev was the rare—perhaps the only—item on the Jewish communal agenda embraced by all. An indication of how strikingly unusual such a consensus was is the Bund’s first response: that only poor Jews figured among the pogrom’s victims, with the wealthy fleeing the violence by hiding in local hotels or leaving by train for Odessa or Kiev. Crucial to Kishinev’s continued impact was Bialik’s famous pogrom poem, which emerged as a clarion call for Jewish activists of all stripes, Zionist as well as socialist. It would be built squarely into the repertoire of Jewish self-defense in Russia and was no less an inspiration for Jewish socialists than it would be in Palestine for the Haganah, which even today traces its start to the poem’s explosive impact.24

Kishinev’s impact was felt deeply at the time even in settings where it was left unmentioned. Its influence on the deliberations of the Social Democratic Party’s Second Party Congress, held in July and August 1903 in Brussels and London—the meeting that first consolidated Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevism and its commitment to the rule of a centralized party—was decisive, despite the fact that the pogrom was barely touched on. In Kishinev’s wake, with the Jewish Socialist Labor Bund all the more intent on being recognized by the party as “the sole representative of the Jewish proletariat,” such preoccupations helped Lenin paint it as hopelessly ethnocentric. The charge rendered the Bund in this internationalist setting all but tongue-tied, vigorous in its (ultimately unsuccessful) resistance to Lenin and his allies but hopelessly vulnerable when confronted with such invectives at a moment when Jewish tragedy weighed so heavily. The Bund’s exit from the congress provided Lenin, much as he had hoped, with the majority he sought—and with Kishinev’s pogrom the dark cloud hanging over the single most formative gathering in the history of Russian Marxism.25

“Even Hell is preferable,” proclaimed Kishinev’s Jewish communal leader Jacob Bernstein-Kogan at the Sixth Zionist Congress in Basel in the summer of 1903.26 This slogan was soon adopted by those supporting the prospect of Jewish settlement in East Africa, an idea proposed by Theodor Herzl and now floated by the British. Elsewhere the insistence by Russian apologists after the massacre that pogroms in the empire’s southern region were no more containable than lynching in the American South prodded Jewish radicals in the United States, in particular, to take a much closer look at the persecution of blacks. The confluence of Russian pogroms and antiblack riots would become one of the age’s most formative lessons in American Jewish radical circles. An eventual by-product would be the formation in 1909 of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which was launched in the New York City apartment of Yiddish-speaking Anna Strunsky and her husband, William Walling, who became the NAACP’s first chairman. At much the same time as they were galvanizing support for a national organization to protect African Americans, Strunsky was struggling to complete a manuscript that she would describe in letters to her family as her “Pogrom” book.27

A still greater influence than the pogrom itself was the document that would cement Kishinev as a catastrophe unlike all others. This was the letter signed by the Russian minister of the interior, Vyacheslav Konstantinovich Plehve, that surfaced a few weeks after the pogrom. Plehve was known for his antipathy toward Jews, whom he undoubtedly loathed, and his letter, dated just before the pogrom’s outbreak, instructed Kishinev’s authorities to avoid all use of force once the massacre erupted. Hence the proof that Russia was unsafe for Jews set it apart from all European countries—except, perhaps, for Romania.

This document was deservedly shocking, and yet there is little doubt, as we will see, that it was a forgery written by those—whether Jewish or not—who sincerely believed its sentiments to be true if impossible to substantiate conclusively. No evidence exists that Plehve wrote the letter, and there is considerable evidence that he did not. (Russian conservatives like Plehve shared an intense distrust of Jews—of their economic rapacity, their radicalism, their incorrigible separatism—but had a much deeper fear of unrest on the empire’s streets.) Nonetheless, widely believed at the time to be true, even by some close to Plehve, the letter rapidly became the prime bulwark for Jewish distrust of conservatism, the most emphatic of all counterarguments to restriction on Jewish immigration, and the most powerful of all justifications for why Jews must flee Russia or fight to bring its government down.28

Oddly, Kishinev’s pogrom would come to occupy a roughly comparable prominence for those on the Russian Right. For them it represented a gruesome moment far more harmful to Russians than to Jews and, like so many others, massaged by Jews for their own benefit. Because of such machinations, world opinion would turn against the regime, and moderates inside Russia would abandon it—all because, as the Right saw it, of outright lies set in motion by Jews and their allies in newspapers throughout Europe and the United States. Shocked by this unprecedented outcry, Krushevan, Kishinev’s most prominent antisemite, rushed into print (in a newspaper he owned) the first version of what would eventually be called The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Scholars now concur that the text was almost certainly his own handiwork in cooperation with a small clutch of far-right figures close to him, nearly all from Kishinev or nearby. Linguistic fingerprints unique to Bessarabia and adjacent regions are studded throughout the original text, though all of these were excised from the better-known, book-length versions published soon afterward. Much as the pogrom proved to Jews and their supporters that the long, wretched arm of the Russian government was behind it all, The Protocols provided no less conclusive proof to antisemites of the limitless power of worldwide Jewry.29

With its imprint so multifaceted, Kishinev’s memory continues to be widely embraced, in contrast to that of tragedies far more murderous that have faded into oblivion, pertinent to few beyond survivors or their relatives. Reviewing in 1923 the first of a projected two-volume work on the pogroms of 1918–20, the Yiddish literary magazine Bikher-velt (Book World) insisted that the book was all the more welcome since these massacres, so devastating at the time, were then disappearing into the mist of history.30 In contrast Kishinev stood there on its own, hugging the beginning of a new century, unmoored to the constitutional crisis of 1905–6, and with its many lessons believed to remain relevant—an unforgettable ingredient of Jewish culture and politics.

How is it that an event so resolutely enters into history that it defines the past and how to behave in the future? What we see here is an inverse relationship between the sheer quantity of available information and a veritable mountain of teachable lessons, many of which at best are only sketchily based on the events themselves. Kishinev’s pogrom may well be the best known of all moments in the Russian Jewish past and the one most persistently, lavishly misunderstood.

Moreover, despite its vaunted standing in contemporary Jewish memory and elsewhere, it was made of so many moments so random, so circumstantial. Had the early-morning rain—which stopped at around six in the morning on the riot’s second day—persisted, the pogrom almost certainly would have ended before the worst of its violence. (Pogroms, like revolutions, occur almost invariably in temperate weather.) Kishinev’s location at the most porous edge of the Russian empire—Bessarabia was the easiest of all places from which to smuggle goods or, for that matter, information—meant that the world was informed of the pogrom’s atrocities with rare dispatch. Had the same events occurred a few hundred miles to the east, it is unlikely that they would have had a comparable impact; the details would have been reported on fleetingly and peppered with fewer updates, and the tragedy, like others then and later, would have almost certainly been mourned locally without much resonance beyond the town itself.

The pogrom revealed Russian Jewry’s inner recesses on the front pages of the world’s press, distilling a coherent set of beliefs about modernity itself. And much of this was the by-product of half-truths, of poetry read as journalism, and of “facts” passed from generation to generation with little basis in fact. The uncanny longevity of beliefs that tumbled from Kishinev’s rubble are crucial to its story; this mix of mythology and countermythology was inspired by a riot in a city barely known of before and rarely spoken about since except as a synonym for devastation.

For example, in the grand, lyrical autobiography of Israel’s first president, Chaim Weizmann, Trial and Error, published in 1949, he describes how as a student and Zionist activist in Geneva in 1903 he had been so crushed by news of the Kishinev pogrom that he rushed immediately to Gomel (in present-day Belarus), where that September he organized the town’s widely lauded Jewish self-defense effort. But in fact it was radicals associated with the Jewish Socialist Labor Bund, with the help of Marxist-Zionists, who organized those efforts. At the time Weizmann was in Geneva, having just returned from Russia. His letters to his fiancée, postmarked Geneva, attest to his whereabouts. Even if Weizmann was not intentionally lying, he told the same story for much of his life. For Weizmann, eventually a towering figure in Russian Jewry, it likely felt quite natural to insert himself into what was the most defining of all contemporary Russian Jewish sagas. He returns time and again in the book to lessons learned from Kishinev—for instance, how to recognize the imprint of mendacious officialdom: “Just before the [1937 Palestinian] riots broke out I had an intimate talk with the [British] High Commissioner. He asked me whether I thought troubles were to be expected. I replied that in Tsarist Russia I knew if the Government did not wish for troubles they never happened.”31

For Noam Chomsky, too—the distinguished linguist and outspoken anti-Zionist who would have agreed with Weizmann on very little else—Kishinev’s lessons are all but identical and no more accurate. In a 2014 National Public Radio interview, he lambasted the Kahan Commission’s comparison of the Sabra-Shatila catastrophe to Kishinev’s pogrom for its failure to take it far enough: “The Kahan Commission, I think, was really a whitewash. It tried to give as soft as possible an interpretation of what was in fact a horrifying massacre, actually one that should resonate with people . . . who are familiar with Jewish history. It was almost a replica of the Kishinev pogrom of pre–First World War Russia, one of the worst atrocities in Israeli memory. . . . The tsar’s army had surrounded this town and allowed for people within it to rampage, killing Jews for three days. . . . That’s . . . pretty much what happened in Sabra-Shatilla.”32

Yet, contrary to Chomsky’s account, the army never encircled the city protecting rioters. For him, much like for Weizmann, the pogrom’s details were part and parcel of common knowledge, an immediate reference point for the widest range of teachable moments.

Ari Shavit’s 2013 best-seller, My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel, places no less than the entire weight of the Zionist enterprise on the shoulders of the Kishinev pogrom, relating it to the story of the expulsion of the Arabs of Lydda (later Lod), the book’s explosive epicenter. He tells of a Lydda that flourished in the Mandate period partly, as he sees it, because it was the site of a Jewish school established for the care of Kishinev pogrom orphans, trained there to become farmers. Once it failed, the school’s buildings were occupied by a full-throated humanistic endeavor launched by a liberal Berlin Jew with a worldview shaped by Martin Buber and the anarchist Gustav Landauer. (The book’s critics insist that the school was actually located in nearby Beit Shemesh, not Lydda.) A generation of displaced German Jewish youth was trained there, schooled in the need for peaceful coexistence with Arabs. At odd hours the students participated in military training as well.33

Then, with the onset of the Arab-Israeli War in 1948, those same students figured among the soldiers who, in July, expelled the nineteen thousand Lydda Arabs, who were forced to walk in suffocating heat, with not a few infants and elderly dying on the long road to the Jordanian border. Shavit writes: “Lydda is our black box. In it lies the dark secret of Zionism. The truth is that Zionism could bear Lydda.”34 Still, he feels contempt for “those bleeding-heart Israeli liberals . . . who condemn what they did in Lydda but enjoy the fruits of their deeds.” Their politics is all the more absurd “[b]ecause I know that if it wasn’t for [Lydda] the State of Israel would not have been born. If it wasn’t for them, I would not have been born.”35 In his view the saga is all the more poignant because at its heart is Kishinev’s pogrom:

Forty-five years after it came into the Lydda Valley in the name of the Kishinev pogrom, Zionism instigated a human catastrophe in the Lydda Valley. Forty-five years after Zionism came into the valley in the name of the homeless, it sent out of the Lydda Valley a column of the homeless. In the heavy heat, through the haze, through the dry brown fields, I see the column marching east. So many years have passed, and yet the column is still marching east. For columns like the columns of Lydda never stop marching.36

Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s late-life historical excursion into Russian Jewish history, Dvesti let vmesti (Two Hundred Years Together), devotes almost an entire chapter to Kishinev’s deleterious impact—on Russians, not Jews. Solzhenitsyn’s argument is that the blanket distrust it created of Russia in the international community and among Russia’s own political moderates and intelligentsia rendered the regime incapable of withstanding the eventual Bolshevik onslaught. Much like Shavit, who draws a straight line from Kishinev to Lydda, Solzhenitsyn situates Kishinev no less emphatically as a station on the road to Bolshevism.37

The pogrom’s durability, its ready slippage into today’s politics, is also made explicit in Benjamin Netanyahu’s frequent comparisons of the Jews of Israel and the massacred of Kishinev. In response to events as varied as the 2012 Toulouse school massacre and the murder of three Israeli teenagers in the West Bank (which was the prelude to the 2014 Gaza war), the Israeli prime minister has referenced Bialik’s Kishinev poetry, long a mainstay of Israel’s school curriculum. Always sidelining in these statements the poet’s warnings of the corruptive impact of violence on all those singed by it, Netanyahu has cherry-picked from this work its apparent calls for reprisal. At the Toulouse memorial service, citing Bialik’s “On the Slaughter”—“The vengeance for a small child’s blood / Satan himself never dreamed”—he chose to overlook the words that come just before: “And cursed be he who cries: vengeance.”38

Finally, comparable to the importance placed on the pogrom in Israel—while drastically different in its details—is its place in the raw, nascent politics of Transdniestria, or the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic, a separatist enclave with a population of five hundred thousand at Moldova’s eastern edge. With its spotlessly clean streets (a sharp contrast to the hurly-burly and cracked sidewalks of today’s Chişinău), sparse markets, and reigning ideology made of old-style Communism and Russian ethnic nationalism, Transdniestria has held on since the early 1990s with its economy in the hands of a clutch of megabillionaires.

History weighs heavily on this place, readily dismissed as one of the world’s last Soviet-style anachronisms. In its effort to claim legitimacy, it holds high among its heroes Krushevan, whose stalwart Russian allegiance, prominence as a Moldavian intellectual, and commitment to what admirers call his “Christian socialism” offer a powerful alternative to the embrace of Western liberal globalism. So argues Transdniestria’s now assistant foreign minister, Igor Petrovich Shornikov—son of one of Moldova’s leading pro-Russian activists—who in 2011 completed the first sustained study of Krushevan’s sociopolitical thought in more than a century.39

Written as a doctoral dissertation at the Shevchenko Transnistria State University, Shornikov’s Russian-language study depicts a Krushevan who had nothing to do with the pogrom or the writing of The Protocols. Jews themselves, in the employ of the Russian secret police—which they assiduously infiltrated—produced the document that Krushevan was somehow persuaded to publish. The pogrom itself, Shornikov argues, was a minor affair blown out of all proportion by Jews who managed to claim far more money for their property than it was worth; the massacre was entirely justified by their economic stranglehold, their outsize political radicalism, and the understandable hatred of those oppressed by them.

All these claims are recycled from the arsenal of Russian conservative and right-wing accounts. Shornikov’s insistence that it was the rapacity and the brashness of Kishinev’s Jews that caused the pogrom cleanses Krushevan—and still more important, all Moldavians—of culpability. As portrayed by this young leader of a Russian-dominated rump state in one of Europe’s most explosive corners, the Kishinev pogrom was a justified, even righteous exercise in self-defense. This is a tale long misconstrued—much like, indeed, the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic itself. Krushevan, long excoriated as a rabble-rouser, is thoroughly rehabilitated as a patriot, a lover of all things Russian—which, as Shornikov argues, is consistent with the staunchest Moldavian convictions. Krushevan’s anticapitalism (interlinked with a relentless hatred of Jews), his insistence on liberalism’s incapacity to challenge either cultural decadence or economic oppression, and perhaps above all his ability to embrace a simultaneous allegiance to both Bessarabia and Russia have managed to transmute the long-forgotten reactionary into a bracingly contemporary influence.

Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History explores how history is made and remade, what is retained and elided, and why. I examine how one particular moment managed to so chisel itself onto contemporary Jewish history and beyond that it held meaning even for those who never heard of the town, know nothing of its details, and nonetheless draw lessons from it. It was a moment that cast a shadow so deep, wide, and variegated as to leave its imprint on Jews, on Jew-haters, and on wounds licked ever since. Studying Kishinev provides the opportunity to cut across standard barriers separating Russian and Jewish, European, Palestinian Jewish, and American Jewish history and to wade through the pogrom’s residue in many different, oddly mismatched corners. Its gruesome stories would frequently outdistance the sufficiently gruesome events themselves. It took weeks for the press to disprove, for example, the widely reported rumor that the bellies of pregnant women had been cut open and stuffed with chicken feathers.40

From the start of my research for this work, it intrigued me that Kishinev’s violence—the worst of it lasting some three to four hours in a cluster of intersecting streets—would come to epitomize this community to a far greater extent than any other moment in Russian Jewish life. These alleyways, especially Aziatskaia, or Asia Street, immortalized now in countless newspaper reports, would become the best known of all Russian Jewish locales, its humble dwellings soon the most telling of metaphors for the impoverishment and grim tenuousness of Jewish life under the tsars. The impact of these impressions, reinforced over the course of the past century, on Jewish perceptions of the world, the designs of gentiles, the exercise of Jewish power, and the immorality of what Netanyahu has derisively called “turning the other cheek” are among the questions that have kept me fixed on this moment and its resilience.41

This, then, is a microhistory as well as an international history of an event that was surely vile but less murderous and less catastrophic than so many others occurring soon afterward—that yet would overshadow nearly all. “The time and place are the only things I am certain of. . . . Beyond that is the haze of history and pain”; this is how Aleksandar Hemon begins his novel The Lazarus Project, built around a bizarre, widely reported 1908 incident in which nineteen-year-old Lazarus Averbuch was shot to death in the home of Chicago’s police chief. Why Averbuch came to the house—he had never before met the policeman—and whether or not he actually threatened the chief’s life, as was reported, remains unclear, but Averbuch’s behavior was irrevocably linked at the time to his having been a witness to the Kishinev pogrom. Hemon writes: “Lazarus came to Chicago as a refugee, a pogrom survivor. He must have seen horrible things: he may have snapped. . . . He was fourteen in 1903, at the time of the pogrom. Did he remember it in Chicago? Was he a survivor who resurrected in America? Did he have nightmares about it?”42

My book, too, explores history’s nightmares. And much like the Averbuch tale, it is a story of the uneasy interplay of truth and fiction—of fiction so unreservedly believed that it would become more potent than most truths. I revisit it in an effort to sort through it so as to better understand the tragedy itself and what was made of it over the course of more than a century. Whether cited explicitly or not, the Kishinev pogrom continues to provide a well-thumbed, coherent road map, one that retains the imprimatur of history. Such accounts are bolstered by the use of evidence recalled endlessly, but such evidence is at best imperfect and—at its worst—not evidence at all.

Kishinev map.

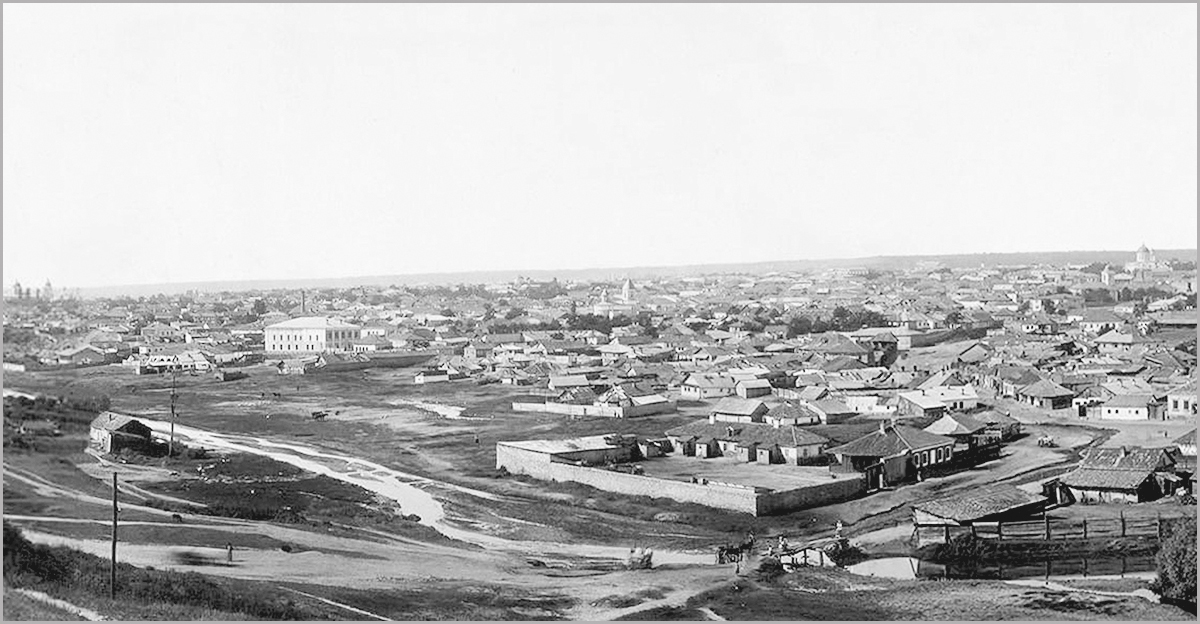

Photograph of Lower Kishinev in the 1880s.