Speed Metal, Slow Tropics, Cold War

ALCOA IN THE CARIBBEAN

Mimi Sheller

INTRODUCTION: LIGHT MODERNITY

Aluminum played a crucial part in creating our contemporary world both in the material sense of enabling all of the new technologies that we associate with mobile modernity, and in the ideological sense of underwriting a world vision (and creative visualization) that privileges speed, lightness, and mobility.1 The material culture of aluminum deeply influenced the ideas, practices, and meanings attached to movement in the twentieth century.2 Aluminum put the world in motion, and the performance of mobility generated symbolic economies revolving around the aesthetics of aerodynamic speed, accelerated mobility, and modernist technological futurism. The built environment that has grown up to support modern mobilities is based on the lightness of aluminum—the engines and bodies of cars, trains, airplanes and rockets; the high-power ACSR (aluminum cable steel reinforced) electricity lines that make up the power grid; the aluminum-clad skyscrapers that gleam in the centers of metropolitan power, starting with the spandrels and window frames of New York’s Empire State Building (built at an astonishing speed of twenty-five weeks in 1930), and reaching a tragic apogee in the aluminum curtain walls of the World Trade Towers that so spectacularly collapsed on September 11, 2001, when struck by the aluminum airplanes turned into unexpected aerial weapons with devastating effect.

Many technologies of mobility and speed depend on the special material qualities of aluminum, but they also depend on the visions of mobility that industry, artists, and advertisers put into motion: a visual semiotics for the technological sublime epitomized by the latest, fastest vehicles and streamlined objects that keep the world moving. The aluminum industry’s design and publicity departments played a crucial part in circulating both visual images of mobility and material objects for mobility, instigating a wider culture of mobility and instilling a positive valuation of lightness and speed. As Florence Hachez-Leroy argues, the market for aluminum was initially nonexistent, and promotion and publicity played a huge part in aesthetically enhancing the appeal of the curious new metal in the 1920s to 1930s, thus requiring the “invention of a market.”3 Yet the design of a material culture of fast, light, streamlined modernism in the United States also generated specific spatial geometries that were not merely representational, but were productive of the political subordination and economic appropriation of places conceived of as nonmodern and peoples conceived of as racialized primitives. Advertising was a productive force, more than simply an act of representation, or even of legitimation. Advertising and industrial design meshed together becoming generative forces of capital and of global political economies in motion.4

The very circuits of cultural production that were necessary for the fantasy of aluminum to take flight also excluded other spaces, imagined (and imaged) as “slow,” regions where people outside modernity can only aspire to modernization, while supplying its raw materials. In particular, this chapter examines how the Caribbean—a key location of both U.S. bauxite mining and tourism in the twentieth century—was imagined, represented, and materially constructed as a place apart, one that lacks the shine of aluminum.5 There was an implicit connection between the production of the material culture and visual image of modernity in the United States in the Age of Aluminum and the parallel consumption of the Caribbean’s raw materials, labor, and visual images of its tropical backwardness. While the aluminum industry took off by promoting a gleaming aerodynamic modernism and supermobility in its primary consumer markets in the United States, it simultaneously benefited from and reproduced a very different image of an as yet unachieved modernization in the “colorful” Caribbean, often depicted as a colonial remnant where cultural change happened more slowly.

In W. W. Rostow’s classic treatise on modernization, The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto, first published in 1960, he describes economic development as a series of stages toward technological maturity that begin with a “takeoff” toward sustained growth.6 The metaphor of modernization as “takeoff” drew on the power of aviation, which is based on the discovery of hardened aluminum, as described below, but also references aluminum’s role in the emergence of new consumer markets based on speedier transport, light packaging, and durable goods. Each society must meet certain preconditions of social structure, political system, and techniques of production in order to take off toward modernity. Modernization was premised on motion—rural to urban, old world to new, sea power to air power—and only with mobility is takeoff achieved into a high-flying era of mass-consumption of durable consumer goods and general welfare. Rostow’s influential thesis was that communist societies were unable to create the preconditions for such a takeoff, but that the noncommunist “developing” societies would eventually get there and join the leaders (Europe and the United States). The very mobility offered by the aluminum industry was both a condition for producing modernity and a metaphor for modernization. Yet Rostow ignored how the takeoff to modernity was premised less on the invisible hand of the market than on the heavy hand of the state and the monopolistic control of primary commodity markets by powerful multinational corporations. To a large extent it was state intervention and business protection that enabled the industrial takeoff of the United States, including the use of patents, cartels, international trade regimes, corporate monopolies, occasional state ownership, and the benefits of military power to ensure access to raw materials in the “developing” world.

During the Cold War, Caribbean states especially suffered from U.S. efforts to quash communism, which also encompassed the suppression of labor unions, social democracies, and independence movements. American dreams of aluminum-based air power and supermodernity occurred at the very time when Caribbean states were attempting to negotiate labor rights, political rights, and national sovereignty, and to negotiate resource sovereignty with multinational aluminum corporations backed by the U.S. government. Aluminum production tends toward an uncompetitive industrial structure. On a continuum of raw material extractive industries, the aluminum industry falls toward the extreme end of relative scarcity, concentration of resources, technology entry barriers (protected by patents and sunk costs), and inelastic demand, encouraging a highly monopolistic or oligopolistic structure. While these structural features do not determine outcomes, they certainly set tight conditions on the possibilities for resource-rich states to bargain with resource extractors.7 But rather than focus on this kind of purely economic history, my aim here is to contextualize the actions of industrialists and states within a cultural history of mobility, with an emphasis on material culture, advertising, and imagined modernities.

The industry’s celebration of its own contributions to technological advancement and to modernization actually masks the behind-the-scenes work that enabled it to lock in immobilities (of technologies, capital, and people), which were often grounded in global economic inequalities that prevented development elsewhere by simply extracting raw materials without any inward investment or societal capacity building. To tell the story of aluminum’s role in modernization—and to write a transnational history of the Americas contra Rostow—one must recombine the North American world of mobility, speed, and flight, with the heavier, slower Caribbean world of bauxite mining, racialized labor relations, and resource extraction. It was, ironically, precisely this juxtaposition of cultural velocities that simultaneously created a market for international tourism, the other great pillar of contemporary Caribbean economies, which also arguably promotes mobility regimes that benefit foreign tourists while demobilizing Caribbean nationals.8

Just as anthropologist Sidney Mintz argued in Sweetness and Power (1986) that the modern Atlantic world was built upon sugar consumption in the age of slavery, we could say that aluminum offers a successor to that story: a late modernity built upon consumption of aluminum and all that it enabled, including speed and mobility itself. The emergence of aluminum reworks the asymmetric material relations and visual circulations between metropolitan centers of consumption and the peripheries of modernity where resource extraction and labor exploitation take place, while just as effectively erasing the modernity and humanity of the workers who produce modernity’s aluminum dreams. This is therefore a transnational story that like other recent commodity histories embeds the United States “in larger circuits of people, ideas, and resources,” rather than stopping at “the water’s edge,” as Robert Vitalis puts it in his study of American multinationals on the Saudi Arabian oil frontier.9

Another version of this transnational history would begin from within the Caribbean, looking outward from the point of view of Surinamers or Guyanese, Jamaicans or Trinidadians; however, given the limitations of space, this chapter only briefly touches upon the West Indian nationalists, internationalists, and labor leaders who struggled to gain control over their own resources, and cannot fully address the desire of Caribbean people to participate in modernization and to possess the new technologies and goods that modernization promised to bring. Aluminum, bauxite, cruise ships, airplanes, and multinational corporations are all social and technological assemblages that transit through a Caribbean that is not frictionless, but highly animated by resistance, by anticolonial and nationalist politics, by islands bristling with literal and symbolic ports for mooring as well as morasses for becoming bogged down. Only by understanding the complex constellations of mobility and immobility that structure transnational American relations can we begin to rethink the cultural motions of Caribbean modernity, and those constellations begin with the emergence of U.S. air power in the early twentieth century.

AIR POWER IN THE AGE OF ALUMINUM

We have often said: just like the nineteenth century was the century of iron, heavy metals, and carbon, so the twentieth century should be the century of light metals, electricity, and petroleum.

—Arnaldo Mussolini, 193210

The rise of an aluminum material culture occurred through a combination of new technologies, new aesthetics, and new practices of mobility. Light metal is what set the twentieth century apart from past eras, and in many ways bequeaths to us today the distinctive look and feel of “late modern” material culture based on aeriality, speed, and lightness, including the mundanely mobile objects of modern household life.11 Built on advances in chemistry and understandings of the forces of electrical current at the atomic level over the course of the nineteenth century, a technological revolution occurred in 1886 with the invention of the electrolytic process that could liberate molecules of pure aluminum from its tightly bonded oxide form. One of the great triumphs of modern chemistry, the dramatic race to invent and secure a patent for making aluminum electrochemically, was achieved simultaneously by a twenty-three-year-old American, Charles Martin Hall, a chemistry graduate of Oberlin College, and a twenty-three-year-old Frenchman, Paul Louis-Toussaint Héroult.12 The combination of electricity and electrochemical production of metals has been called the second industrialization, replacing the iconic canals, water power, coal, iron, and steam of the first industrial revolution. We might think of this as a shift from heavy to light modernity. Within a few decades the “speed metal” played a crucial part in the development of lighter vehicles and airplanes, lightweight objects and packaging, and national public infrastructures for transportation and electricity. Aluminum consumption growth rates exceeded those of all major metals in the twentieth century.13

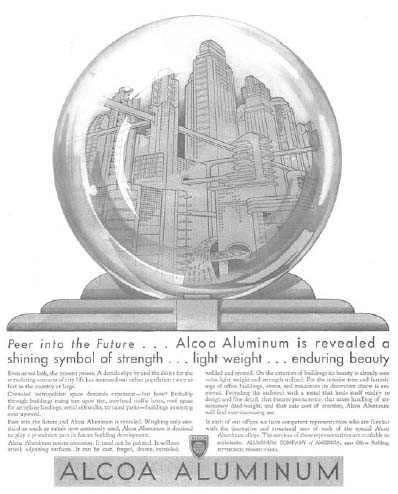

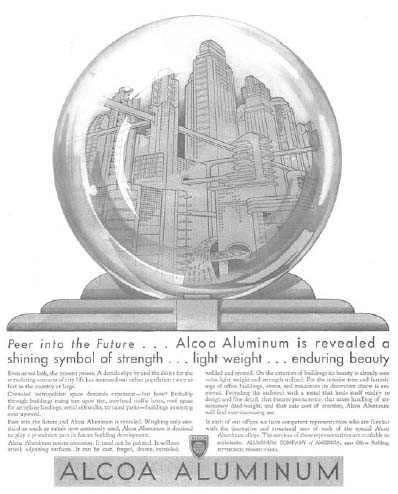

While still having to overcome difficulties in the production process due to the unique qualities of aluminum, including huge requirements for electricity and the need to develop various alloys and anodized surfaces, applied engineers gradually recognized aluminum as an unusual material that was light yet strong, flexible and easily workable, quick to assemble and disassemble, easy to maintain, and reusable and recyclable. The weight of aluminum is about one-third of an equivalent volume of steel (with a specific gravity of 2.70 versus steel’s 7.85), so engineers can use it to achieve dramatic weight reductions.14 This made it especially attractive in the aviation and transport industries; it could contribute to weight, labor, cost, and time savings. But beyond these practical properties, it also became a significant marker of modernity as a visual symbol of streamlined aerodynamic speed, clean gleaming lines, and the imaginative design of a futuristic world, as seen in early advertising campaigns by the Aluminum Corporation of America (Alcoa) (Figure 6.1).

This was not the first time a new material had transformed the world. Walter Benjamin has written eloquently about the cultural impact of cast iron, which contributed new materials and visions for the transformation of Paris in the 1820s to 1850s into a glittering city of arcades, grand boulevards, and exciting railways. In his Arcades Project he spins out a web of cultural connections from the cast iron structures of the gas-lit arcades to the new department stores and the cavernous railway stations, into an entire world of capitalist spectacle and new modern attitudes.15 This was the beginning of a movement toward modernity, and a fascination with the speed of the galloping stagecoach and soon the steaming locomotive thundering on its iron rails, with the instantaneity of daily newspapers and the fascination with kinetoscopes and moving pictures.16 Combined with steel, and later with plastics, aluminum would open whole new vistas in the quest for speed, and a new material culture of soaring urban heights and glass curtain walls. It would truly bring the apotheosis of speed and the new architectures of luminosity that nineteenth-century writers dreamed of, thrilled at, and feared. Aluminum eventually enabled the flights to the moon first envisioned by Jules Verne, the science fiction writer who recognized aluminum’s potential in his 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon, when this mysterious light element was still a rare and expensive precious metal.

FIGURE 6.1: Alcoa aluminum ad, “Peer Into the Future,” Fortune, ca. 1931. Author’s private collection.

The discovery of aluminum smelting emerged from the 1850s to 1880s, the same period as the invention of cinema. Fast-motion photography was built upon photochemistry and electric triggers, which made instantaneous photographs possible, just as chemistry and electricity together make aluminum possible.17 Rebecca Solnit has observed that it was the railroad baron Leland Stanford who supported the experiments of photographer Eadweard Muybridge while he carried out his famous motion studies of racehorses. The railroad and the instantaneous photograph became the progenitors of mechanized moving pictures on perforated celluloid strips, as well as the violent means by which Native Americans were pushed off their lands (as the railroad expanded European settlement across the continent), only to be preserved as shadow figures in the Wild West shows and the Hollywood westerns.18 Aluminum technology plays a similar role in the invention of the Tropical South: its advancement was paradoxically the means of both intensifying U.S. occupation and use of Caribbean land, while also reproducing romanticized visual representations of exoticized storybook lands as the basis for new forms of appropriation via tourism—both thanks to Alcoa, which grew out of the Pittsburgh Reduction Company that was founded upon Hall’s and Héroult’s combined patented smelting process.

Alcoa’s expansion into the Caribbean was closely linked to wartime military needs. Duralumin is an extremely strong heat-treated alloy of aluminum with small percentages of copper, magnesium, and manganese, developed by German metallurgical engineer Alfred Wilm in 1909. It became the basis for the building of Zeppelin airships during Word War I, instigating a race between Britain and the United States to try to develop their own airships.19 In the end it was the war itself that enabled Alcoa to expand its bauxite mining operations into Suriname, and to gain access to the exact details of the Duralumin patent via the U.S. Alien Property Administrator and “industrial espionage from English and German companies,” according to Margaret Graham. After the war U.S. technical missions from the Bureau of Construction and Repair gained access to the German state aluminum works at Staaken and entered plants in England and France. “The result,” says Graham, “was Alcoa’s 17S, an alloy almost identical in composition to Duralumin.”20 With this “effectively stolen technology” Alcoa drove ahead in its pursuit of new strong alloys, and eventually came up with a thin sheet metal known as Alclad—with a strong alloy core and surface layers of corrosion-resistant pure aluminum integrally bonded to the core—which was indispensable in the development of military and civil aircraft.

Early military uses were crucial to the development of new markets for the metal, including its use in aeronautical engines, aircraft, bombs, explosives, fuses, flares, hand grenades, heavy ammunition, identification tags, machinery, mess kits, motor cars, naval ships, rifle cartridges, trucks, tanks, utensils, and water bottles. Military and later civilian aviation became the most important industry in the widespread use of aluminum, beginning with frames, instruments, and propellers, and extending into many other parts of the aircraft. In May 1927 Charles Lindbergh made the first successful solo nonstop transatlantic flight in his single-seat, single-engine Ryan NYP, the Spirit of St. Louis, which had a Wright Whirlwind J-5C engine containing a substantial amount of Alcoa aluminum. His success contributed further to aluminum becoming firmly entrenched in the U.S. aviation industry. During the First World War about 90 percent of all aluminum produced was consumed by the military, whose requirements for 1917 and 1918 totaled 128,867 tons, while in the Second World War, some 304,000 airplanes were produced by the United States alone, using 1,537,590 tons of metal.21 Flight also brought new technologies of visualization (such as aerial photography and eventually satellite visualization), which were often first exercised in the conquest of colonial empires, along with aerial bombardment.22

Aluminum is one of the most abundant minerals on earth, and the most commonly occurring metal, but it is economically recoverable only in limited forms and limited locations. One of those locations is the Caribbean. The successful expansion of the market for aluminum in the 1930s and 1940s, and even more so into the 1950s, required a steady supply of high-quality bauxite. Suriname, where Alcoa first opened mines in 1916, became a key supplier, while its Canadian sister company Alcan sourced its bauxite in British Guiana. But the threats posed by German U-boats to trans-Caribbean shipping during World War II prompted an interest in securing steady supplies closer to the U.S. mainland, including Jamaica, where bauxite ore was discovered only in the 1940s. The increased demand for aluminum during the Second World War, the emergence of the United States as the world’s largest aluminum producer, and the dangers of wartime shipping all led to the emergence of Jamaica as the primary supplier of bauxite to the U.S. aluminum companies.23 The system of Allied collaboration known as “Lend-Lease,” along with the September 1940 destroyers-for-bases agreement, also enabled the United States to provide aluminum to British wartime industries (whose European sources of bauxite and power had been seized by Germany) in exchange for air bases in British colonies, including Jamaica, Trinidad, and British Guiana.24

These new military bases embodied the waning of Britain’s power in the region and gave the United States a valuable military foothold just as U.S. multinationals were engaging in bargaining over access to resources, preferential tariffs, and deals for low taxation.25 Bauxite mining underpins a crucial connection between the production of the material culture and visual image of modernity in the United States and the parallel consumption of raw materials and visual images of tropical backwardness in the Caribbean. Surprisingly, the material circulation of mining and light metals is also intimately linked with the embodied practices of tourism that connect the Caribbean and the United States. The aluminum industry interlaced military mobilization and modern economic development in North America, on the basis of control over Caribbean resources, with leisure travel and its visual imagery. A West Indies lacking the luster of metallic modernity was represented as a backward region beckoning American enterprise and adventure. The following sections juxtapose promotions of aluminum as a “speed metal” in the U.S. market with a striking series of luxury magazine advertisements promoting the Caribbean tourist cruises of the Alcoa Steamship Company from 1948 to 1958. This is the period in which Alcoa became the biggest producer of aluminum in the world and depended to a large extent on bauxite mined in Jamaica and Suriname, the two largest exporters of bauxite in the world. In the midst of corporate transnational expansion, aluminum became a significant marker of national modernity, a symbol of streamlined aerodynamic speed, whose curvaceous gleaming lines linked it to the imaginative design of a future world, but one from which the Caribbean was excluded.

THE SPEED METAL

When our boys come flying home from victory, they’ll fly straight into a new Age of Aluminum … a plentiful supply of the miracle metal that does so many things so much better.

—Reynolds Aluminum ad, 1943

Aluminum moves around the world, changing shape as it moves. It also shapes infrastructures and remakes the “spatiotemporal fix” that locks in certain kinds of mobilities and immobilities. Aluminum became crucial not simply as a new material out of which to make particular objects, but because it contributed to an entire shift in the style of “stuff”: the styling of vehicles, buildings, infrastructure, and all around design of the objects of everyday life. Its cultural currency eventually spanned high culture and low culture, city and suburb, indoor intimate objects and outdoor monumental structures, high tech and homey, all linked to a national project of modernization through mobility. Its fluid forms together reshaped the places and networks that enabled its own movements and the movements of others. While it is somewhat fluid, it nevertheless also locks in certain systems, technologies, and infrastructures, which then become difficult to undo. Aluminum can ultimately be thought of not just as a metal, but as a complex network of actors and the connections between them; all such networks are heterogeneous, partial, and only to some degree stable, thus it is crucial to understand how they are stabilized, and how they may also be destabilized through “situated actions.”26

The qualities of aluminum were an important aspect in the construction of what David Nye calls the “American technological sublime,” which could be found in spectacular electrical displays, giant infrastructural projects, or impressive displays of machinic dynamism and speed.27 Quixotic Italian Futurists like F. T. Marinetti embraced mechanized speed, metallic lightness, and ultimately air power, proclaiming in his Futurist Manifesto (1909), “we create a new god, speed, and a new evil, slowness. … If prayer means communicating with the divine, racing at high speeds is a prayer.” Alcoa’s advertising of the 1930s already makes clear the revolution that aluminum had sparked in transportation and mobility. A 1930 ad from the Saturday Evening Post declares that “Soon—nearly all Trucks and Buses will have Aluminum Bodies,” and describes how “truck and bus bodies that are 1,000 to 6,600 lbs. lighter now speed over the highways.” While detailing the savings made in various transport businesses, the ad also highlights other benefits: “Today you may ride in an aluminum train, for several railroads operate trains with cars built largely of Alcoa Aluminum Alloys. All-aluminum planes carrying passengers, merchandise, and mail, reduce coast-to-coast trips to 48 hours. Aluminum trolley cars operate on regular schedules in city and suburbs.”

Alcoa’s fiftieth anniversary message, printed in Fortune magazine in May 1936, gives a good feel for the novel sense of great lightness and increased mobility that aluminum afforded to the transportation sector:

Aluminum was ready to answer the call for lightness in all moving things: the automobile engine piston, the bus body, the truck body, all moving parts, all mass-in-motion, and finally, the streamlined railroad trains. …

For the day of lightness is here. The swan song of needless weight is being sung. Aluminum has become the speed metal of a new and faster age. Side by side with older metals it is giving you faster transportation, with greater safety and economy.

Lightness and speed enable efficiency and economy. Lightness combined with strength made aluminum the perfect substance for the new transportation system, and through this quality it came to be associated with speed and a “new and faster age” as the ad puts it. The rise of aluminum occurred through a combination of new technologies and research and development, but also through stylish marketing and the popularization of new modernist aesthetics whose counterpoint was the slower pace and naturalism of tropicalized island spaces and races.

In the United States, companies like Alcoa, Bohn, Reynolds, and Kaiser played an important part in promoting innovation in the use of aluminum and imagining the light modernity of the future. A new vision of an aluminum-based modernism was further shaped by maverick inventors, designers, and dreamers like William Bushnell Stout, a pioneering aircraft designer, whose 1936 aluminum-bodied Stout Scarab was a minivan-like vehicle with a folding table and swivel seats. Stout’s motto was “Simplicate and add lightness.”28 Wally Byam, the travel enthusiast who created the Airstream trailer, led the international caravan club that made the trailers world famous by journeying in them across Africa, Latin America, and Asia.29 Even more influential was R. Buckminster Fuller, the eccentric inventor who designed the all-aluminum Dymaxion house in the 1930s, the aluminum-bodied Dymaxion car in 1933, and eventually the geodesic dome that achieved world fame as the centerpiece of the U.S. Information Agency’s American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959. The streamline aesthetic was also advanced by designer Norman Bel Geddes, whose Motor Car Number 8 sported a teardrop-shaped body. Geddes was the creator of the 1934 “Century of Progress” exhibition at the Chicago World’s Fair and the General Motors Pavilion “Futurama” exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair (whose theme was “The World of Tomorrow”), which brought viewers riding on moving chairs equipped with sound into a futuristic 1960s world of fantastical skyscrapers, seven-lane highways, and raised walkways, “proposing an infinite network of superhighways and vast suburbs.”30 These future visualizations and simulations shaped the actual material cultures of later decades, as they were realized in material form by the industrial designers, architects, and engineers of modernity.

Above all, the aerial superiority of aluminum over all previous metals made possible what cultural theorist Caren Kaplan calls “the cosmic view” of militarized air power. “Mobility is at the heart of modern warfare,” writes Kaplan, and “modern war engages the theories and practices of mobility to a great extent.”31 It is lightweight aluminum-clad bombers that made such a change in military practice possible, later joined by guided missiles, satellites, and rockets. Weaponization of the air expanded through Major Alexander De Seversky’s famous book Victory Through Air Power (1942), which was also made into a Walt Disney animated feature film of the same name. In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, wide distribution of the book and the film are said to have influenced both Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt and to have changed national military strategy forever. Wartime air power was supported by the government’s massive investment in aluminum production, which was transferred over to civilian capacity after the war’s end in part through the breakup of Alcoa and transfer of its assets over to Reynolds and Kaiser. U.S. government investment drove aluminum production to grow by more than 600 percent between 1939 and 1943, outpacing the increase in all other crucial metals.32 During the war the United States produced 304,000 military airplanes in total, using 3.5 billion pounds of aluminum, claiming more than 85 percent of Alcoa’s output.33 So important was its role in winning the war, some have even called it “the metal of victory.”34 At war’s end the government had $672 million invested in fifty wholly state-owned aluminum production and fabrication plants, which were disposed of after the war through the Surplus Property Act.35

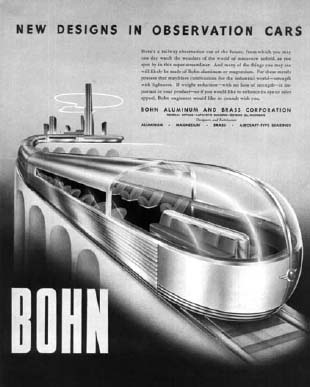

The striking advertising imagery created in the early 1940s by the Detroit-based Bohn Aluminum and Brass Corporation—which specialized in design and fabrication of aluminum, magnesium, and brass—exemplifies how a wartime technology was transformed into a vision of futuristic modernism that was exploited to make the economic transition from military to civilian applications of aluminum. Bohn designers envisioned a world populated by new futuristic machines made of aluminum and glass—everything from cars, trains, buses, and planes to lawn mowers, tractors, helicopters, and combine harvesters. Ads from the 1940s make explicit the push to unleash the potential of aluminum research and design to transform the mechanized world and remake the built environment, showing how lightness, mobility, and speed were consciously injected into the U.S. landscape: “Today America’s manufacturing processes are concentrated solidly on war materials for Victory. From this gigantic effort will spring many new developments of vast economic consequence to the entire universe. The City of the Future will be born—startling new architectural designs will be an every day occurrence!” A metallic glass-fronted streamlined railcar pulls away from a city of modern skyscrapers: “Here’s a railway observation car of the future, (figure 6.2) from which you may one day watch the wonders of the world of tomorrow unfold, as you spin by in this super-streamliner. And many things you see will likely be made of Bohn aluminum or magnesium. For these metals possess that matchless combination for the industrial world—strength with lightness”.

Even more fanciful departures from existing designs include oversized farm and industrial machinery described as Tomorrow’s Power Shovel, a Future Cotton Picker, a Possible Tractor of Tomorrow, and a rocket-powered transoceanic “Dreamliner.” The series is attributable to the well-known futurist graphic artist Arthur Radebaugh, who worked in Detroit where the company was also based. Radebaugh was known for his luminous airbrush illustrations of futuristic vehicles and cities, especially for MoTor Magazine and the Detroit automobile industry, and he deeply influenced the streamline aesthetic and later science fiction illustrators. Radebaugh’s “imagineering” depicted a futuristic world of human conveyor belts, glass-domed Futuramas, elevated expressways, amphibious cars, and moveable sidewalks. Harvey Molotch argues that art “radiates visions that span across actors and industrial segments. Art brings enrollment,” as inventors, investors, power sources, patents, producers, promoters, and consumers are all enrolled into making and using something new in the world.36 Radebaugh’s art in the Bohn ads does precisely that. His fantastical images of soaring metropolises with high-speed levitating trains, personal helicopters, zeppelin mooring masts, and so on drew on the capacities of aluminum to make possible a new lightweight and malleable architecture of the future.

FIGURE 6.2: Bohn ad, Fortune, ca. 1943. Author’s private collection.

Thus from a wartime resource of national strategic importance, the aluminum industry mutated into a multifaceted industry that not only produced goods, but produced the capacity to consume more electricity, to transport more goods, and to keep the economy on the move more quickly. Design historian Dennis Doordan argues that the “Age of Aluminum did not just happen; it was designed to happen, consciously designed by industrial designers working within the framework of the aluminum industry to provide technical information and to promote a climate conducive to creative engagement with aluminum.”37 Aluminum companies “worked to stimulate a climate of creative engagement with aluminum on the part of independent designers” with industry publications including “essays on themes such as creativity, innovation, and the phenomenon of change.”38 Doordan argues that the design departments at Alcoa, Reynolds, and Kaiser Aluminum were in the business of placing knowledge and facilities at the disposal of other designers and fabricators, through a creative collaboration. They were not simply designing objects, but also information.

For example, in 1952 Alcoa hired the advertising agency Ketchum, Macleod, and Grove, who produced a marketing campaign that they called FORECAST. They announced that the campaign’s “principal objective is not to increase the amount of aluminum used today for specific applications, but to inspire and stimulate the mind of men.” They devised a multifaceted marketing campaign with weekly magazine advertisements, the publication of a periodical called Design Forecast, and commissions for twenty-two well-known designers to create products using Alcoa aluminum. The practice of forecasting and scenario building employed in this advertising campaign built on the practices of the RAND Corporation, a major player in research and development for the military-industrial complex.39 They were spreading the news of aluminum’s possibilities, stoking dreams of its future potential, and assisting designers and fabricators in turning it into new products.

If corporations were in the business of designing information as much as objects, then their advertising tells us a great deal about what information they wished to circulate and what they wished to keep quiet. Rather than reading the thrilling images of futuristic modern mobility from within a hermetically sealed U.S. national context, it is necessary to follow the silvery thread of aluminum back on its journey out of the ground of Jamaica, Guyana, and Suriname, and into the hopes, dreams, and images it set in motion around the Caribbean, where the majority of the bauxite for the North American smelters originated and where the aluminum companies promoted tourist cruises. What information about the Caribbean was designed into industry publicity? And what alternative meanings of mobility did Caribbean actors attempt to bring to bear on the shaping of mobile modernity? The following section turns to Alcoa Steamship Company advertising campaigns that are situated in this context of the promotion of speed and lightness in American consumer culture; but behind it lies the tough bargaining between multinational corporations with strong financial (and ultimately military) backing from the U.S. government and weak British Caribbean states under pressure from economic stress, colonial social mobilizations, and independence movements.

CRUISING THE CARIBBEAN

Behind Caribbean romance lurks an export market. SURINAME—Thousands of East Indians contribute an Arabian Nights touch to this equatorial land. They also are part of a thriving Caribbean market that needs razors, sewing machines, autos, machinery and other products manufactured here in the U.S.A.

—ALCOA Steamship Company Ad, Fortune, ca. 1948

The Caribbean has long served as a site of tropical semimodernity, set apart from the modern West through forms of colonial exploitation and imperialist exotification of its “colorful” people, “vivid” nature, and “dream-like” landscapes.40 The cool space-age futurism of aluminum modernity had to be constructed via its contrast with a backward, slow world that happened to lie next door: the American fascination with the steamy jungles of the tropics, the hybrid races of the Caribbean, and the image of “the islands” as primitive, backward neighbors. This grammar of difference helped to construct what anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot calls “the Savage Slot,”41 yet it depended on making invisible the power of U.S. corporations to control and monopolize the mining and processing industries that make modern technology possible, and the military power that it enabled and required. It also hid the emerging modernities of the Caribbean itself, especially its political modernity, which was subsumed beneath the romantic naturalism of tourism and at best acknowledged as a potential market for American-made goods as in the epigraph opening this section. This was a representation challenged by actors within the region, including labor leaders, consumers, and political economists.

The Alcoa Steamship Company played a special role in the Caribbean, not only shipping bauxite and refined alumina to the United States, but also carrying cruise ship passengers, commissioning artists to depict Caribbean scenery, and even recording Caribbean music and sponsoring the Caribbean Arts Prize in the 1950s. The company operated three “modern, air-conditioned ships,” each carrying sixty-five passengers, which departed every Saturday from New Orleans on a sixteen-day cruise, making stops in Jamaica, Trinidad, Venezuela, Curaçao, and the Dominican Republic.42 These ships became not simply a conduit connecting different modernities, but were precisely one of the means by which divergent North Atlantic and Caribbean modernities were produced. David Lambert and Alan Lester argue that the “travel of ideas that allowed for the mutual constitution of colonial and metropolitan culture was intimately bound up with the movement of capital, people and texts between these sites, all dependent in the last resort on the passage of ships.”43 The mobility and increasing speed of ships as steam replaced sail in the nineteenth century reconfigured the space of the Atlantic world as “a particular zone of exchange, interchange, circulation and transmission,” suggests David Armitage.44 And as Anyaa Anim-Addo elaborates in her work on the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company in the Caribbean, “The RMSPC’s ships offered an alternative modernity to the railway but also, as mobile places, provided a shifting experiential modernity at various points along the ship’s routes.”45 It was precisely in riding onboard ships such as Alcoa’s cruise liners, and in consuming their touristic visual grammars, that divergent mobile modernities were constituted, lived, and materialized.

The ship en route was a space of travel and mobility between allegedly separate worlds—one fast and modern, the other traditional and romantically slow—yet ironically those worlds were connected by the material potentialities of aluminum that arose directly out of the ground of the Caribbean. Alcoa’s three new ships, built by the Oregon Shipbuilding Co. in 1946, were test beds for Alcoa’s new magnesium-silicide alloy 6061, thus becoming a doubly material and symbolic realization of mobility on display:

These liners, the S.S. Alcoa Cavalier, Clipper, and Corsair used alloy 6061 for deckhouses, bridges, smokestack enclosures, lifeboats, davits, accommodation ladders, hatch covers, awnings, weather dodgers and storm railings, all connected with 6053 rivets. Other alloys, both wrought and cast, were used for doors, windows, furniture, electrical fittings, décor and for miscellaneous applications in the machinery space.46

The ships themselves, with their extensive aluminum fixtures and fittings, advanced technology, and modernist design, were at once floating promotions for potential investors, displays of the material culture of aluminum’s light modernity, and a means of consuming mobility as touristic practice. Passengers on the three ships were given pamphlets including “Let’s Talk about Cruise Clothes,” “Taking Pictures in the Caribbean,” and “Your Ship: Alcoa Clipper,” which described the extensive use of the light metal in the ship, from the superstructure to the staterooms: “Almost anywhere you happen to be on Your Ship you will find some use of aluminum.”47 Thus the ships combined industrial mobilization of commodities, multisensory touristic mobilization of a mobile gaze, and subtle symbolic mobilization of the signs and icons of mobile modernity.

The same economic, political, and spatial arrangements that locked in huge market advantages for transnational mining corporations simultaneously opened up Jamaica and other Caribbean destinations for tourism mobilities. Tourism then instigated the circulation of new visual representations and material means of movement through the Caribbean. While Alcoa promoted novel products, modern skyscrapers, and metallurgical research and development in the United States, the company promoted the Caribbean as a source of bauxite, positioned it as a potential market for “superior” American products, and envisioned it as a timeless destination for tourists traveling on its modern ships to safely step back into the colorful history, exotic flora, and quaint folkways of diverse Caribbean destinations. While these modes of both imaging and moving are not surprising (and continue in other ways today), what is striking is the degree to which the Caribbean produced here diverges from the futuristic images of supermodernity that were simultaneously being promulgated in the U.S. consumer market for aluminum products. Appearing in the luxury publication Holiday magazine, the advertising images seamlessly meld together tourism, business travel, bauxite shipment, and cultural consumption, yet carefully detach these Caribbean mobilities from the light, sleek modernity being envisioned and promoted at home in the United States, in magazines such as Fortune, and onboard the ships themselves.

The ads also strikingly ignore or erase the presence of modern technology in the Caribbean, including U.S. military bases and the emerging infrastructure of modern ports, urban electrification, and eventually airports. As Krista Thompson has shown in her study An Eye for the Tropics, photographic images of the Caribbean produced for tourist markets in the early twentieth century tropicalized nature by emphasizing lush and unusual plants, exoticized local people by showing them in rustic and primitive settings, and erased signs of modernity such as electric power lines or newer urban areas. It is American tourists and modern North American ships that seem to move, while the Caribbean islands and people are pinned down like butterflies to be collected, catalogued, and made known. Here I focus on three moments of the erasure of Caribbean modernity, showing how the motions of the Alcoa ships produce the spatial disjunctures of divergent modernities through their representational practices and cultures in motion.

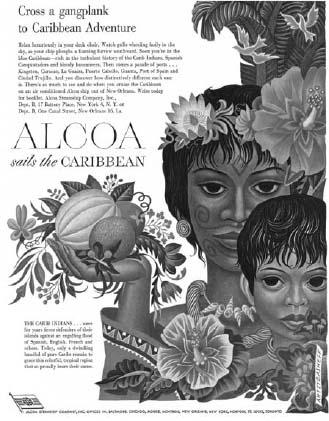

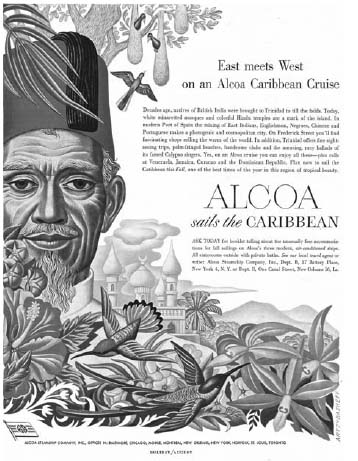

Tourists, Primitives, and Modern Workers, 1948–52

The first series of ads, which ran from 1948 to 1949, was created and signed by the graphic artist Boris Artzybasheff. A Russian émigré to the United States, Artzybasheff was most well known for his cover portraits for Time magazine, his colorful series of Shell Oil ads, and his surreal drawings of anthropomorphic machines. For the Alcoa Steamship Company he produced an unusual series of portraits of Caribbean people. A Carib mother and child, for example, are depicted as timeless primitives, holding up fruit and peering out from dark eyes and exotically painted faces (Figure 6.3), in a region described as “rich in the turbulent history of the Carib Indians, Spanish Conquistadors and bloody buccaneers.” Afro-Creole women appear in typical poses such as “[d]ark-eyed senoritas, descended of conquistadores of old” or a stereotypical “Creole belle,” wearing a madras head tie and gold jewelry. Each image represents an example of racial blending or distinctiveness, portraying a male or female racialized persona in typical costume, including Carib Indians, various types of Afro-Caribbean “blends,” East Indian Hindu and Muslim, and even various types of Creole “whites” of Spanish, Dutch, or Anglo-Caribbean origin. Although the images appear at first to promote cultural encounter and ethnological curiosity within touristic contact zones, such typifying images circulate within a long lineage of tropicalizing representations of Caribbean islands and people.48

FIGURE 6.3: Boris Artzybasheff, Alcoa Steamship Co. ad, Holiday, February 1948. (Author’s private collection.)

Setting apart the modern U.S. consumer/tourist from the ersatz primitive populations of the tropics, the text of this series emphasizes the swashbuckling colonial history of the Caribbean, which marked the region with diversity: “[I]f you look carefully you’ll see how the distinctive architecture, languages and races of this area have been blended by centuries into interesting new patterns.” This kind of typifying imagery relates to earlier colonial racial typologies and Spanish castas paintings, which attempted to portray all of the racial “types” found through mixtures of different kinds. Each image includes a distinctive flower, colorful foliage, and often a typical bird or butterfly, suggesting a kind of natural history that conjoins island people and wildlife, naturalizing races through attachment to profusely tropical places. This is a mode of visualization that solidifies Caribbean difference as a material, natural, textural distinction that sets “the blue Caribbean” apart from the mainland world inhabited by allegedly modern subjects. Above all, this “tourist gaze” produces a visual grammar of difference.49

While suggestive of the complex global mobilities of people and cultures, these historically anchored images fix the Caribbean in time as a series of romantic remnants that exist for the edification and consumption of the modern, mobile traveler. Hindus and Muslims appear in unusual hats in front of their exotic temples, suggesting the mobility of cultures into the colonial Caribbean (see Figure 6.4). A Dominican sugarcane cutter appears as noble worker in one image, with the tools of his trade in hand. Yet the images simultaneously paper over the ethnic, class, and color hierarchies that fanned political unrest throughout the postwar Caribbean; they offer not only a visually flattened perspective, but also a historically and socially flattened one. Left-wing Guyanese labor leader Cheddi Jagan noted in 1945 that wages for workers were “only one-third to one-quarter of comparative wages in bauxite and smelting operations in the United States and Canada,” and he dreamed of an independent nation with its own aluminum industry.50 Ironically, in this very period Alcan’s DEMBA mine in British Guiana (part of Alcoa when built) was using racial and ethnic divisions of labor to reinforce the occupational and political divisions between Guyanese of African and East Indian descent, and class hierarchies between black and white.51 The DEMBA workers engaged in a sixty-four-day strike in 1947, but struggled to form an effective union in the face of company paternalism and tight discipline.

FIGURE 6.4: Boris Artzybasheff, Alcoa Steamship Co. ad, Holiday, August 1948. (Author’s private collection.)

The Caribbean claims one of the most mobile working classes in the world, but it was foreign corporations that governed the patterns of labor migration—whether to work on the sugar plantations of other islands or the banana plantations of Central America or in the building of a transisthmus railway and the Panama Canal. This mobile working class was at times highly politicized, cosmopolitan, and critical of the world economic system. Ideologies such as Garveyism, pan-Africanism, socialism, and communism circulated among them, and between the Caribbean and its U.S. outposts in places like Harlem.52 The most organized workers in the region were the stevedores and other port workers who, along with sugar plantation workers, led major strikes including the “labor rebellion” of 1937–38.53 Both Guyanese and Jamaicans in the labor movement struggled to shift the terms of their enrolment in the world economy and transform the ways in which their natural resources (and labor) were being mobilized for the benefit of others.54 Only a Venezuelan worker placed in front of what is described as a “forest of picturesque oil wells,” holding a sturdy wrench among some delicate pink flowers, hints at a modern industrial economy taking shape in the Caribbean, but one that is described as “hungry for American-made products—and all that their superiority represents.” The feminization of the worker and naturalization of the industrial landscape suggest an awkward attempt to fit industrialization into older tropes of Caribbean island paradise. A postcard titled “Alcoa bauxite,” for example, captions its image from Trinidad, “The delicate pink blush on the Tembladora Transfer Station is from raw bauxite ore from which Aluminum is made.”

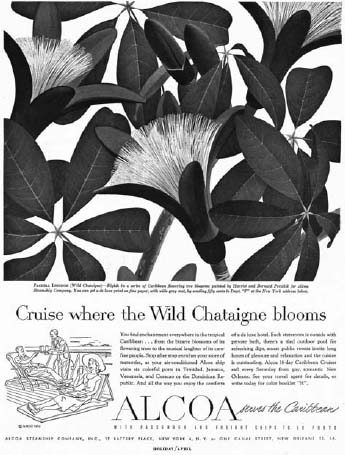

FIGURE 6.5: Harriet and Bernard Pertchik, Alcoa Steamship Co. ad, Holiday, April 1951. (Author’s private collection.)

The protean Caribbean appears here as a series of renaturalized yet traditional places, outside of modernity yet accessible to the mobile tourist, a “paradise for travelers, export opportunity for businessmen.” Special editions of some of the images, suitable for framing, could also be ordered by mail, creating a Caribbean souvenir to take home. A second related series of ads, published in 1951–52, depicts botanical paintings of tropical flowering trees (figure 6.5) by the respected botanical illustrators Harriet and Bernard Pertchik. These images tap into a long tradition of botanical collection and illustration of tropical plants by colonial naturalists, who collected material in the Caribbean and incorporated it into systems of plant classification and medical knowledge.55 Natural beauty is valued here in a visual economy of touristic consumption, even though the modern light mobility of the American tourist is predicated on clearing and strip mining Caribbean forests for the precious red bauxite ore below them. Tourists themselves are depicted in the corner of each ad, frolicking on the modern space of the ship in motion. The same corporation that transports bauxite out of the Caribbean on its freighters not only carries tourists in, but also through its advertising incites the consumption of new modern products in the U.S. consumer market while the cruise experience itself produces the mobile modern subjects who will consume such products. This constellation of modern mobile subjectivity is explicitly contrasted against the slow, backward, romantic tropics; yet the market relations and power relations that produce these conjoined uneven modernities (including U.S. military bases) are like photographic negative and positive, each a condition for the other.

Bauxite, Folk Dance, and Vernacular Styles in Motion, 1954–59

As Jamaica adopted universal enfranchisement in the 1940s and moved toward self-government in the 1950s, there was “an increasing sense of nationalism and concern for the protection of national resources,” especially among the labor parties of the left.56 Out of the labor movement arose a generation of nationalist leaders who pushed the British West Indies toward independence, and toward democratic socialism. In October 1953 the British government, with U.S. support, forcibly suspended the constitution of Guyana and deposed Jagan’s labor-left government, elected by a majority under universal adult suffrage, when he threatened to take back mineral resources and move the colony toward independence.57 Coming just as the government was in the process of passing a Labor Relations Bill that would have protected unions and labor rights, the coup nipped in the bud Jagan’s longer-term plans to create forward linkages through locally based aluminum smelters and fabrication plants using the country’s significant potential for hydropower. Bolland argues that the “consequences of the suspension of Guyana’s constitution and subsequent British actions were devastating for the development of politics in the colony,” leading to a deep racial split within the People’s Progressive Party, and long-lasting racial polarization between Afro-Guyanese and Indo-Guyanese.58 These events make evident the external control over labor movements in the region, and the degree to which they would not be allowed to assert resource sovereignty.

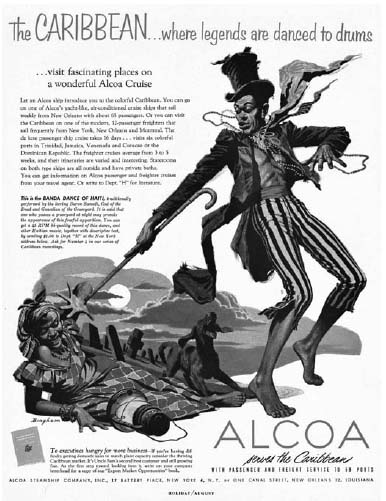

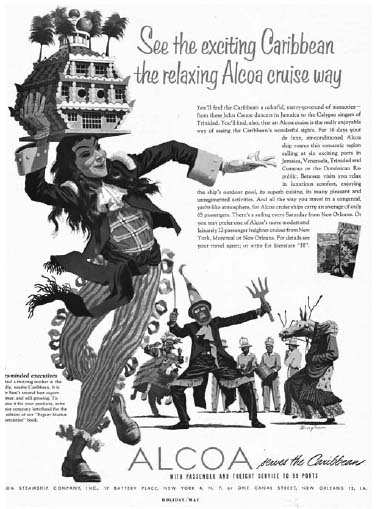

It is in this historical context that we can read the third Alcoa Steamship series, which ran from 1954 to 1955, a striking set of folkloric portrayals of musical performances, parades, or dances, both religious and secular, by the graphic illustrator James R. Bingham. Readers are encouraged to write in to purchase 45 rpm recordings of the music that accompanies some of the dances, including the sensationalized Banda dance of Haiti, associated with foreign misrepresentations of “Voodoo” (Figure 6.6), the Joropo of Venezuela, the Merengue of the Dominican Republic, and the Beguine of the French West Indies.

FIGURE 6.6: James R. Bingham, Alcoa Steamship Co. ad, Holiday, August 1955. (Author’s private collection.)

Other ads represent the Pajaro Guarandol “folk dance of the Venezuelan Indians,” the steel pan and “stick dance” of Trinidad, the “Simadon” harvest festival of Curacao, the folk dance of the Jibaros of Puerto Rico, and the John Canoe dancers of Jamaica (figure 6.7) whose costumes date back to the eighteenth century and possibly to West Africa. This series connects touristic consumption of musical performances from across the Caribbean with an almost ethnographic project of investigation of traditional cultures and people who persist outside of modernity, a remnant of the past available for modern cruise tourists to visit, but also, as the ads note, “Uncle Sam’s biggest export customer, and still growing. To appraise it for your products, write on your company letterhead for the 1955 edition of our ‘Export Market Opportunities’ book.”

FIGURE 6.7: James R. Bingham, Alcoa Steamship Co. ad, Holiday, May 1955. (Author’s private collection.)

Folkloric music was played by costumed performers for the benefit of tourists. Caribbean national elites had an interest in furthering these projects of self-exotification for the tourist market, just as they had an interest in encouraging foreign investment, whether in agriculture or mining. They tried to keep their towns looking quaint and not too modern in order to encourage tourism. When modern buildings such as a new Hilton Hotel were built in the 1950s or 1960s, they became enclaves of modernity for visiting tourists from which the local populace was excluded except as service workers. Yet seldom has the direct connection between the two industries been noted: the mining of bauxite made possible the mobilities of tourism, while the touristic visualization of the Caribbean supported the materialities of dependent development that kept the Caribbean “backward” and hence picturesque.59 So in a sense the absence of aluminum architecture, vehicles, power lines, and designer objects came to define Caribbean material culture, which in contrast came to be associated with the rustic, quaint, vernacular, handmade island tradition, using natural materials and folk processes.

However, the people of the Caribbean were at the same time contesting such images, insisting on their own modernity. Independence movements in the postwar period began to call for self-rule, while migrants to London, New York, and other metropoles, along with the radio, carried styles of modern urban cultural consumption back to the Caribbean; and Caribbean styles of modernity were themselves carried into the metropole, “colonization in reverse” as Jamaican performance poet Louise Bennett called it. The potential circuits of travel of the musical recordings and dance styles hint at the powerful cultural currents emanating out of Caribbean popular cultures and circulating into U.S. urban culture via Caribbean diasporas. Despite the appearance of frozen tradition in Bingham’s portrayal of these folk dances, the vivid forms of dance and music also attest to a kind of cultural vitality that could quite literally move people in unexpected (and possibly dangerous) ways.60 Writers, musicians, intellectuals, and artists grappled with the meanings of Caribbean modernity, and produced their own visualizations of the Caribbean past, present, and future.

In 1956 changes in the internal and external political situation led into a new conjuncture for bargaining between the Jamaican state and the transnational corporations. A major renegotiation of the terms of bauxite royalty payments and taxes was undertaken by People’s National Party Chief Minister Norman Washington Manley (one of the founding fathers of Jamaican independence) in 1956–57, based on the principle that “[c]ountries in the early stages of economic development ought to derive the largest possible benefits from their natural resources. They ought not to be regarded merely as sources of cheap raw materials for metropolitan enterprises.”61 In October 1957 the Soviet Union launched the first Sputnik satellite, a small aluminum orb that triggered the Space Race with the United States. This, along with the Korean War, made aluminum an even more crucial “strategic material.” Jamaica moved from supplying about one-quarter of all U.S. bauxite imports in 1953 to over one-half in 1959, with 40 percent of total shipments of crude bauxite and alumina between 1956 and 1959 going into the U.S. government stockpile.62 Following tough negotiations, the 1957 agreement reset the royalty paid on ore, which led to a substantial increase in revenues to the Jamaican government. Bauxite royalties contributed more than 45 percent of the country’s export earnings by 1959.63

Caribbean Modernity in Motion, 1962–75

Ironically, in 1960 the Alcoa Steamship Company was forced to decommission its three beautiful passenger ships, due to high costs, union struggles, and a cost-saving shift to Liberian flags of convenience.64 A confidential internal memo at the time noted that the company would shift to chartered foreign flag freighters: “Taking advantage of the lower foreign flag operating costs, we will be able to save an estimated $2,077,000 per year immediately and $2,296,000 per year after the passenger ships are sold. … This will eliminate jobs for American seamen and there is never a good time to do this particularly when foreign seamen will benefit.”65 The memo goes on to note, “The passenger vessels have undoubtedly been our best form of public relations. However, the Steamship Company, by itself, can no longer justify this costly form of public relations.” They would also have to cancel the cruises booked by twenty-six couples, many of whom were “customers of the Aluminum Company of America” and “prominent people.” The most serious problem, however, was that the workers on the ships were primarily Trinidadian and “some smattering of Surinamers,” who belonged to the Seamen and Waterfront Workers’ Union in Trinidad, which at the time was trying to organize with the Seamen’s International Union to strike against the cost-saving move. Alcoa executives noted that with the help of the powerful United Fruit Company they would be able to challenge the legality of such strikes, and force the workers out of their jobs before new labor contract negotiations took place.66

Jamaica achieved independence in 1962 when it “was the world’s largest producer of bauxite” according to historical sociologists Evelyn Huber Stephens and John Stephens. “In 1965, the country supplied 28 percent of the bauxite used in the market economies of the world … [and] bauxite along with tourism fueled post-war Jamaican development and the two provided the country with most of her gross foreign exchange earnings.”67 Newly independent Caribbean countries took pride in their mining industry. The $10 note from the Bank of Guyana carries an image of bauxite mining workers on the left, and of a glistening alumina reduction plant on the right. A 2 shilling stamp from Jamaica depicts modern machinery engaged in gathering the deep red ore of a bauxite mine. In the same year of Jamaica’s independence, the fifty-foot antenna of the American Telstar satellite, which used 80,000 pounds of aluminum, beamed the first satellite television pictures back to a transmission station in Maine, ushering in the dawning of satellite telecommunications and new dreams of the gravity-defying lightness of the Space Age. Caribbean leaders also desired to escape their colonial past in order to embrace exactly the kind of modernity that U.S. technology promised. They shared the dreams of the Space Age, the prosperity that mining and alumina reduction promised, and the light modernity that aluminum could bring.

Yet the demise of the cruise ships indicates how multinational corporations were evolving into global transnational corporations. American workers would also suffer the consequences as industrial production began its shift to other parts of the world, and containerization undercut the bargaining power of port workers’ unions. This was accompanied by another shift in modernization strategies, from sea power to aerial power. Ships were no longer suitable publicity machines for the company, as attention shifted to the new civilian aircraft that were coming into use. In 1965 Alcoa created the “FORECAST Jet,” a kind of “flying showcase” that displayed the company’s products and services. Described as “an aeronautical ambassador of aluminum,” the DC-7CF could be expanded on the ground into a reception area formed by “a semi-circular screen of aluminum beads,” with aluminum spiral stairs rising up to an interior conference lounge furnished with woven-aluminum panels, aluminum-fabric upholstery, aluminum sand-casted lighting fixtures, and artworks in aluminum. The jet “functioned both as a sign and signifier of its product as well as a metaphor for the new postwar corporation … the aluminum airplane—the war machine of World War II—transformed into a sleek communication machine in the Cold War marketplace.”68 Like the Alcoa Steamships, these “communication machines” suggest the close relationship among material objects, semiotic meanings, advertising, and the advance of industry as intertwined actors.

Caribbean cultures were also in motion, promulgating their own communication machines. The New World Group of economists at the University of the West Indies began to publish scathing critiques of foreign capital and the economic underdevelopment of Jamaica and began to call for the nationalization of the Jamaican bauxite industry in the early 1970s. The socialist government of newly independent Guyana nationalized the Demerara Bauxite Company in 1970 and took a 51 percent stake in Alcan’s DEMBA subsidiary. In 1973 Prime Minister Michael Manley’s People’s National Party government “opened negotiations with the aluminum TNCs on acquisition of 51 percent equity in their bauxite mining operations, … acquisition of all the land owned by the companies in order to gain control over the bauxite reserves, and a bauxite levy tied to the price of aluminum ingot on the U.S. market.”69 In March 1974, inspired by the success of OPEC, a bauxite producer’s cartel known as the International Bauxite Association (IBA) was set up and was quickly able to double the price of bauxite on world markets.

However, Manley’s socialist rhetoric, friendship with Fidel Castro, and support for African liberation movements such as the MPLA (Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola) in Angola did not endear him to the United States, or to the multinationals. In response, American aluminum companies “doubled their bauxite imports from Guinea in 1975, [and] they reduced their Jamaican imports by 30 per cent. … Jamaica’s share of the world market for bauxite plummeted.”70 The corporate powers that controlled the global aluminum industry would never allow “Third World” countries, especially socialist ones, to wrest control over their own resources. The bauxite taken from the Caribbean allowed the United States to build a material culture of light aluminum, unquestionable military air power, and space-age mobility. At the same time, the terms of oligopolistic international trade and market governance that allowed this transfer of resources to take place helped to lock in place structures of global inequality that prevented Caribbean countries from exercising true sovereignty or benefiting from their own resources—for them Rostow’s “takeoff” never came.71 Instead, the Caribbean remained a tourist mecca, frozen in folkloric performances of the colorful past embellished with tropical foliage, for mass market tourists who now arrived on jets built with Alcoa aluminum. Some countries turned toward offshore banking, a different strategy for leveraging the high-speed mobilities of finance capital, while other actors resorted to the underground movement of drugs and weapons as part of the hidden but vast “narcoeconomy.”

CONCLUSION

The emergence of aluminum-based practices of mobility, alongside modern ideologies and representations of that mobility, pivoted on the coproduction of other regions of the world as backward, slow, and relatively immobile—“bauxite-bearing” regions that would be mined by multinational corporations for the benefit of those who could make use of the “magical metal.” Such relative mobilizations and demobilizations are constitutive of the connections and disconnections between North America and the Caribbean, with patents, tariffs, tax regimes, and military power locking in the spatial formations that allow disjunctive modernities to exist side by side. The airy lightness of aluminum and its associated visualizations of metallic modernity were wrenched out of the tropical earth of specific places, subjected to modern forms of domination and associated pollution.72 Toxic red mud from bauxite mining, water and air pollution from alumina refining, excessive energy use for aluminum smelting, and negative health effects on workers and nearby populations are as much a product of the Age of Aluminum as are elegant MacBook Air notebook computers with their “featherlight aluminum design” and promise of mobile connectivity at our fingertips. Advertising and alluring objects continue to enroll us in the fantasy of mobile modernity, while tourist mobilities hide the global rifts on which easy circulation is premised.

By closely examining the aluminum industry’s material objects of lightweight modernity alongside its visual representations of its bauxite mining lands in the Caribbean as tourist destinations, this chapter has tried to reconnect the valuation of modern U.S. American mobility with the practices of transnational heavy industry, warfare, tropical dispossession, and economic inequalities upon which it depended. These dichotomies are in truth the two inseparable sides of the same coin. The colonial mobilities of the Caribbean held it in a kind of slow motion, while the postcolonial struggles for democratic socialism and resource sovereignty locked the region into conflicts that were geared to spur the fast-forward motion of the United States while indefinitely delaying the Caribbean takeoff toward the promise of modernity.

It seems fitting that in March 2008 the first European Space Agency Automated Transfer Vehicle, which docked successfully with the International Space Station, was launched on an aluminum Ariane 5 rocket from Kourou, French Guiana. The vehicle is appropriately named “Jules Verne.” Gazing toward the heavens, an observer of the historic launch might not have noticed the displaced Saamaka Maroons living as nonnational migrants on the fringes of the neighboring French territory of Guyane, a former penal colony known for its brutal and deadly prisons, but where the capital Cayenne is now the location of the European Space Programme.73 These descendants of runaway slaves who gained treaty rights to an independent territory in the jungle interior of neighboring Dutch Guiana in the eighteenth century lost a huge portion of their homeland in 1966–67 when Alcoa built the Afobaka hydroelectric dam and an artificial lake to power their aluminum smelter at Paranam, displacing thousands of Maroon villagers.74 The modernizing society of Guyane “is trying so hard to replace its image as a penal colony with that of gleaming Ariane rockets,” writes Price, but here again two modernities jarringly converge at a crossroads of sharp contrasts between the traditions of the Maroon past and the gleaming outer-space future.75 These Caribbean footnotes to the metropolitan world’s technological achievements ought to draw our attention back down to the ground of Suriname, Guyana, and Jamaica, where an analysis of the mobile and immobile material cultures afforded by aluminum can elucidate not only the cultural history of technology, design, and popular culture, but also the broader currents of global political economy, mobile modernity, and its sites of contestation.