Pika

Do we even need an introduction to mammals? We are mammals. We’re well schooled in the salient characteristics of mammals. Most mammals give birth to live young; yet egg-laying platypuses are mammals and live-bearing snakes are not. We are all warm-blooded, that is, we maintain a constant relatively warm body temperature; but so do the birds and, arguably, the bees.

In mammals only, a coat of keratinous hairs serves to insulate the body, so hair may be the definitive mammalian body part, since only half of mammals (the females) produce milk. Whales, armadillos, and other mammals even less hairy than we are all have at least a few hairs at some developmental stage. Mammal coats come mainly in shades of brown and gray. Even on the few mammals, like skunks, with “showy” rather than cryptic coloring, no fur is bright blue or green, as some feathers are. Most mammals need to be inconspicuous. They achieve that by wearing camouflage colors, by being quiet and elusive, and by being nocturnal. That makes mammal-watching a less popular pastime than bird-watching, and makes mammal tracks, scats, and other signs the key to being woods-wise to mammals. Mammals learn to avoid popular hiking trails. I’ve often begun to see more of them as soon as I got even a hundred yards off trail. The mammals we see most often each have reasons to be unafraid: porcupines are spiky, bears are big, squirrels go up, marmots and pikas go down, and National Park–dwelling deer, elk, and goats take advantage of their protected status. Watch out for them!

Small mammals are especially limited to the murky corner of the spectrum. Experienced field naturalists can sometimes recognize the species they study, using color differences they have learned in a particular locale. They may report these shades as “dusky” or “buffy,” “tawny” or “ochraceous”—terms less useful to nonscientists. The animals themselves vary. In a given species, there may be different shades for different seasons, for juveniles versus adults, for infraspecific varieties and color phases, for the paler underside and darker back, and between the hair tips, underfur, and guard hairs. Among closely related mammals, populations of dry regions are often paler than their wet-side relatives, each tending to match the color of the ground so as to be less visible to predators (especially owls) that hunt from above in dim light. Dry country has pale dry dirt, whereas moist forests have dark humus and vegetation.

Positive identification of small mammals utilizes the number and shape of molar teeth, and caliper measurements of skulls and penis bones (a feature of most male mammals); the creature must first be reduced to a skeleton. Don’t worry, this chapter will not go into molar design or the meaning of “dusky,” but will offer size, tail:body length ratio, form, habitat, and sometimes color, to facilitate educated guesses as to small mammal identities. Our typical glimpse of a shrew, mouse, or vole, unless we trap it or find it dead, is so fleeting and dark that we can only guess based on habits and habitat.

Ochotona princeps (ock-o-toe-na: their Mongolian name; prin-seps: a chief). Also cony. 8 in. long if stretched out, but appearing a thickset 5–6 in. long in typical postures; no tail; brown; ears round, ½ in. across. On talus, in CasR and CoastM. Ochotonidae.

Pika

Pika haystack.

A cryptoventriloquistic nasal “eeeenk” in the vicinity of coarse talus (rockpile) identifies the pika for you. Look carefully for it on the rocks. You might see it as a rodent, but the posture is rabbit-like— the sharply nose-down head angle, the neck drawn back in an S curve.

Pikas are year-round (nonhibernating) warm bodies in cold climates, clad in appropriately warm fur coats. There’s a down side to that: being out and about for more than a few minutes on a hot day kills them. They stay cool by retreating deep into the talus, where it is never hot, even during most forest fires. So they are absolutely dependent on talus. The question is whether they are dependent on cold climates. If so, they could be poster children for species threatened by climate change. It’s true that nearly all populations of this species are up at high elevations, and that a few Nevada mountain ranges have lost their pikas within recent decades.

Here in Cascadia, most of our pikas are up high, but numerous colonies thrive close to sea level in the Columbia Gorge, where there have been 90°F days nearly every year for as long as records have been kept. Close study finds that Gorge pikas and alpine pikas lead very different lives. Alpine pikas spend many months a year under the snow, eating “hay”—vegetation they spend summer industriously gathering from nearby meadows and curing in “pika haystacks.” A hotter climate may not allow them enough hours aboveground in summer to harvest the several bushels of hay each pika needs. Gorge pikas, in contrast, eat a lot of moss, which is about as fresh and available in winter as in summer, so they don’t store much hay. The moss grows right on the talus, too, so that they can find some even under snow or ice (which they only suffer for a few weeks a year) as well as in the heat of summer. Mammals don’t generally eat much moss, which isn’t very nutritious. Exactly how that challenge affects Gorge pikas is not known; I doubt they could increase the moss portion of their diet from what it is now.

The big question is whether pikas elsewhere will adapt to warming by forging new lifestyles. It’s a tall order. Young pikas dispersing from their natal talus have to find talus habitat soon—a severe restriction on migration, as it prevents crossing most lowlands. (Pikas never managed to reach the Olympics after the last ice age.)

The young disperse and make their own hay their first summer, even if they’re only half grown. A youngster’s prospects are favorable only when there’s room for them somewhere on that rockpile they call home—typically near the pile’s center, since outer sites near the meadow belong to dominant individuals. Trying to disperse farther is fatal more often than not.

You’re most likely to spot haystacks under rock overhangs in talus; others are deep in the rockpile. Haystacks are prone to rotting, and pikas include some highly phenolic (mildly toxic) plants to inhibit rot. The phenols degrade with age, allowing the cured hay to be eaten. Pikas graze on grasses in summer, but turn to more phenolic perennials and even woody plants for haymaking.

“Eeeenk” calls carry far, for such a small creature. They can express either territoriality or alarm—the two salient features of a pika’s so-called social life. Pikas are intensely antisocial, attacking other pikas that infringe on their territories (except of course when they’re ready to mate).

On the other hand, the colony is critically important, if only for the alarm system embodied in “eeeenk!” The alarm call is used for larger predators but not for weasels and martens; they’re small enough to chase pikas in rockpiles, so it’s better to quietly disappear into the maze. According to more than one report, a pika may be aided by other pikas coming out from refuge to distract the weasel by running around like crazy. Such reports set naturalists to arguing over whether it’s altruism (evolved traits endangering individual lives for the benefit of the genetic group) or merely foolish nervous agitation.

“Pika” derives from the way Siberian Tungus tribespeople say “eeeenk,” so it should be pronounced “peeeeka.” I hear that pronunciation in Canada, but south of the 49th I’ve mostly heard “pike-a,” perhaps due to confusion with “pica” or “piker.”

Lepus americanus (lep-us: their Roman name). Also varying hare. 16 in. when stretched out, + 1½-in. tail; gray-brown to deep chestnut brown in summer; in winter, High Cas and e-side race turns white, with dark ear-tips; w-slope race stays brown; ears slightly shorter than head. Nocturnal and secretive; widespread in mainland forest. Leporidae.

Snowshoe hare

Thanks to their “snowshoes”—large hindfeet with dense growth of stiff hair between the toes—these hares can be just as active in the winter, on the snow, as in summer. They neither hoard nor hibernate, but molt from brown to white fur, and go from a diet of greens to one of conifer buds and shrub bark made all the more accessible by the rising platform of snow. They make the animal tracks we see most often while skiing. They also become the staple in the winter diet of several predators—foxes, great horned owls, golden eagles, bobcats, and especially lynxes. Though the hares’ defenses (camouflage, speed, and alertness) are good, the predator pressure on them becomes ferocious when the other small prey have retired beneath the ground or the snow. Hares can support their huge winter losses only with equal summer prodigies of reproduction, which we call “breeding like rabbits.” Several times a year, a mother hare can produce two to four young. She mates immediately after each litter, and gestates 36 to 40 days.

Drastic population swings in 8- to 11-year cycles are well known in northerly parts of showshoe hare range, but not here. The other kind of varying the hare is named for—from summer brown to winter white pelage—is true of some hares here. The semiannual molt is triggered by changing day length. In years when autumn snowfall or spring snowmelt come abnormally early or late, the hares find themselves horribly conspicuous and have to lay low for a few weeks. Permanently brown races have evolved in lowland areas that fail, year after year, to develop a prolonged snowpack—for example our west-side foothills and mid-elevations. These brown hares stand out during the occasional snows. The rest of the year they make the most of their camouflage, foraging by dawn and dusk, and sometimes on cloudy days in deep forest. Snowshoe hares don’t use burrows, but retire to shallow forms under shrubs.

Though infrequently vocal, snowshoe hares have a fairly loud aggressive or defensive growl, a powerful scream perhaps expressing pain or shock, and ways of drumming their feet as their chief mating call. A legendary courtship dance, in which they may literally somersault over each other for awhile, appears to crescendo out of an ecstatic access of foot-drumming.

Several other kinds of hares and rabbits live in Northwest lowlands and steppe, venturing into the margins of our range. Physical differences between hares and rabbits are arcane, but there’s a big difference in life history: hares (Lepus spp.) are born fully furred, ready to run and eat green leaves within hours; rabbits, born naked and blind, nurse for 10–12 days before leaving the nest.

Sorex spp. (sor-ex: their Roman name). Mouse-like creatures with long, pointed, wiggly, long-whiskered snouts, red-tipped teeth, and hairless tails. Soricidae.

Dusky shrew, S. monticolus (mon-tic-o-lus: mountain-dweller). 2¾ in. + 1¾-in. tail; dark brown. Forests from n OR north.

Wandering shrew

Wandering shrew, S. vagrans (vay-grenz: wandering). 2½ in. + 1½-in. tail; fur dark gray frosted brown on back, pinkish on sides, and pale on belly. Wet forest and meadows both low and high.

Western water shrew, S. navigator. Also S. palustris. 3 in. + 3-in. tail; blackish above, paler beneath; tail similarly bicolored. In and near high-elev marshes and lakes.

Marsh shrew, S. bendirii (ben-dear-ee-eye: for Charles Bendire, p. 342). 3½ in. + 3-in. tail; blackish all over. W-side lowlands, often in water.

Trowbridge shrew, S. trowbridgii (tro-bridge-ee-eye: for William P. Trowbridge). 2½ in. + 2¼-in. tail; gray-black except white underside of tail. Lower w-side forests; not on VI or CoastM.

Masked shrew, S. cinereus (sin-ee-rius: ashen). 2¼ in. + 1¾-in tail; brown with tan underside. Drier mtn forests, WA and mainland BC.

Shrews, our smallest mammals, lead hyperactive but very simple lives. As shrew expert Leslie Carraway writes, “S. vagrans exhibits some behavior that tends to indicate it does not perceive much that transpires in its microcosm.” Day in and night out, shrews rush around groping with their little whiskers, sniffing, and eating most everything they can find. This goes on from weaning, between April and July of one year, until death, generally by August of the next.

They eat insects and other arthropods (often as larvae), earthworms, and a few conifer seeds and underground-fruiting fungi; they have been known to kill and eat other shrews, and mice. They have cycles of greater and lesser activity, but as a rule they can’t go longer than three hours without eating, and the smaller species eat their own weight equivalent daily. As with bats and hummingbirds, such a high caloric demand is dictated by the high rate of heat loss from small bodies: at two grams, masked shrews approach the lower size limit for warm-blooded bodies. Baby shrews nurse their way up to this threshold while huddling together so that the combined mass of the litter of four to ten easily exceeds two grams. Whereas bats and hummingbirds take half of every day off for deep, torpid sleep (p. 358), shrews never do. Nor do they hibernate. It’s hard to imagine how our shrews meet their caloric needs during the long snowy season when insect populations are dormant, and heat loss all the more rapid. But they do—or at least enough of them do to maintain the population.

One cause of mortality seems to be a sort of Shrew Shock Syndrome triggered, for example, by capture or a sudden loud noise. Some scientists relate it to the shrew’s extreme heart rate (1200 beats per minute have been recorded) and others to low blood sugar caused by even the briefest shortage of food. At any rate, it is common to see little shrew corpses on the ground. With poor eyesight and hearing, shrews are ill-adapted to evade predators. Their defense is simply to be unappetizing. Owls, Steller’s jays, and trout are on the short list of predators known to have a taste for shrews.

Marsh and water shrews, the ones most likely to tempt trout, spend much of their time in the water, going after aquatic insects and larvae, snails, leeches, and so on. Their fine, dense fur traps an insulating air layer next to the skin, giving them enough buoyancy to scoot across the water surface for several seconds. When they dive and swim, they have to paddle frenetically to stay under, aided by stiff, hairy fringes on the sides of their hind feet. As soon as they stop, they bob to the surface. Yet marsh shrews can stay down for three minutes and more. Underwater, they have a silvery coat of little bubbles coming out of their fur.

Our more terrestrial shrews may run on the ground or even climb trees, but more of the time they are subsurface. Dusky and vagrant specialize in the duff layer; others use existing vole runways; and the bigger, stronger Trowbridge’s burrows in mineral soil.

The first four species listed above are all part of a closely related group that is not yet well sorted out. New species names in the group have been assigned, but it remains difficult to assign old behavior and distribution records to the correct new name.

Shrews are ferociously solitary. In order to mate, they calm their usual mutual hostility with elaborate courtship displays and pheromonal exchanges—a real-life “taming of the shrews.”

Neurotrichus gibbsii (new-rot-ric-us: hairy wire, i.e., tail; gib-zee-eye: for G. Gibbs, p. 171). 3 in. + 1½-in. tail; gray-black; tail hairy (unlike any other shrew or mole); teeth not red-tipped; eyes tiny; no visible ears; forefeet and claws larger than rear ones, but less so than in moles; snout long, whiskered. Mainly in w-side forest; not on VI. Talpidae.

Shrew-mole

The shrew-mole is barely bigger than shrew-sized, yet it is a mole, genetically. Behaviorally, it’s less into burrowing and more into life above ground, even climbing bushes in search of bugs.

Scapanus spp. (scap-an-us: digger). Burrowing animals, blackish with pink, naked tail and snout; eyes and ears barely visible; forefeet huge, turned-out, heavily clawed. Talpidae.

Coast mole, S. orarius (or-air-ius: coastal). 5 in. + 1¼-in. tail. Widespread in OR and WA, barely into BC.

Townsend’s mole

Townsend’s mole, S. townsendii (town-zend-ee-eye: for John Kirk Townsend, p. 350). 7 in. + 1½-in. tail. W-side meadows, up to subalpine; CoastR and OlyM.

Moles are so specialized for burrowing that they practically swim through loose soil. Their forelimbs are hyperdeveloped, while the pelvis and hindlimbs are small and weak. Eyes and ears are both almost entirely overgrown with skin and fur so as not to clog up with dirt. While the eyes barely function at all, the ears are quite sharp at receiving earthborn sounds, enabling the mole to detect and hunt earthworms (its main food) by sound.

These two moles are commonest in lowland pastures, but the coast mole also inhabits forests in most parts of our range, and both species are sometimes found in subalpine meadows. Each individual defends its own network of tunnels, which lack entrance holes. Coast moles usually tunnel just below the surface, pushing up sinuous ridges of soil. Townsend’s moles tunnel several inches down, and get rid of the dirt by pushing it up to form numerous mole hills. These are symmetrically volcano-shaped, in contrast to fan-shaped gopher mounds; they may have a vertical hole in the center, or you may be able to expose one by digging a little.

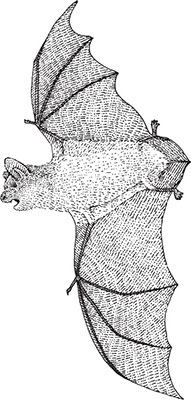

Bat

As evening gets too dark for swifts and nighthawks to continue their feeding flights, bats and owls come out for theirs. Though our largest bats and smallest owls overlap in size—around 5½ inches long with a 16-inch wingspread—bats are easy to tell from owls by their fluttering, indirect flight. Our species never venture out in the daytime, so you are unlikely to see one well and I won’t identify our ten or twelve species individually.

Among mammal orders, only rodents are a larger population than bats, which probably take a bigger slice out of the insect population than any other type of predator. Bats catch flying prey either in the mouth or in a tuck of the small membrane stretched between the hind legs; the mouth then plucks it while the bat tumbles momentarily in mid-flight. Each wing is a much larger, transparently thin membrane stretched from the hindleg up to the forelimb and all around the four long “fingers.” Since the wing has no thickness to speak of, it is less effective than a bird or airplane wing at turning forward motion into lift. To compensate, bats generally have much greater wing area per weight than birds, and use a complex stroke resembling a human breast-stroke to pull themselves up through the air. Bats are slower flyers than birds, but much more maneuverable, able to pursue flying insects rather than just intercepting them.

Bats roost upside down, hanging from one or both feet, often in large groups. Daytime roosts during the active season include caves, but more often tree cavities and well-shaded branches. They sleep all day and hibernate all winter upside down. (A few species fly south instead.) Our bats typically hibernate in caves, which provide stable above-freezing temperatures and high humidity. Some males mate very aggressively, others so sneakily that the female appears unaware that anything is going on. Our bats mate in autumn, then typically delay fertilization and bear a single pup in spring. Still hanging upside down, for a few weeks the mothers nurse almost constantly except while out hunting. Coming in from the hunt to a colonial roost, they are fairly accurate in picking out their own pup.

Bats may carry rabies, but even rabid ones rarely bite people.

Since 2006, a fungal disease called white-nose syndrome has afflicted bats in eastern North America, nearly wiping out entire cave populations. Though there are few records of it, so far, from west of the eastern Great Plains, a single bat crippled by white-nose turned up in the west-side Cascade foothills in 2016. White-nose appears to be a Eurasian pathogen that Eurasian bats are resistant to, most likely brought to North America by humans. It’s going to be hard times for North America’s bats, but there is hope that selected bat caves could be fumigated to offer refugia where species can persist long enough to evolve resistance.

Out of the 4000-plus species of mammals living today, almost 1700 are rodents, and almost 1300 of those, or 32 percent of all mammalian species, are myomorphs, or mouselike rodents. As with insects, songbirds, grasses, and composite flowers, such disproportionate diversification bespeaks great success in recent geologic times.

Of the numerous rodent families, seven appear in this section.

Aplodontia rufa (ap-lo-don-sha: simple teeth; roo-fa: red). Also mountain-beaver, sewellel, chehalis. 12- to 14-in. rotund body; tail vestigial, inconspicuous, 1–2 in.; dark brown above, slightly paler beneath; with blunt snout, long whiskers, small eyes and ears, long front claws. Shrubby moist habitats; OR, WA, BC CasR. Aplodontidae.

Boomer

Boomers are big, slow, nearly tailless, partly arboreal, mostly burrowing rodents. They achieve several distinctions, all rather ludicrous. They host the world’s largest (⅜ inch) species of flea. They are the only surviving species in the most primitive living family of rodents, having changed little since they first appeared, very early on in the evolution of rodents. Naturalists never quite know what to call them, apart from “living fossils.” Most manuals list them under mountain-beaver, but then apologize that this is neither a beaver nor especially a mountain-dweller. Everyone in my end of the county that has boomers calls them “boomers,” despite their relentless failure to boom. Well, they might “moom” from time to time—sort of a low moan, repeated.

Boomers prefer wet, scrubby thickets and forests at all elevations. They thrived in the 20th century, with the proliferation of second-growth timber. They honeycomb their half-acre home ranges with shallow burrow systems, making molehill-like dirt heaps and marmot-like burrow entrances with fanned-out porches. Mainly nocturnal, they are active year-round, eating sword ferns and bracken, vine maple and salal bark, and Douglas-fir seedlings. The latter makes them unpopular with foresters, of course, but their digging does a lot for soil drainage and friability, and disseminates spores of desirable underground-fruiting fungi.

Castor canadensis (cas-tor: their Greek name). 25–32 in. + 10- to 16-in. tail; tail flat, naked, scaly; hind feet webbed; fur dark reddish brown. In and near slow-moving streams. Castoridae.

American beaver

The beaver is by far the largest North American rodent today, and was all the more so 10,000 years ago, when there was a giant beaver species the size of a black bear. Of all historical animals, the beaver has had the most spectacular effects on North American landforms, vegetation patterns, and Anglo-American settlement. If that’s not enough, it’s also Oregon’s state animal.

Though beavers themselves are infrequently seen by hikers, they leave conspicuous signs—beaver dams, ponds, and especially beaver-chewed trees and saplings.

The sound of running water triggers a dam-building reflex in beavers. They cut down poles with their teeth and drag them into place to form, with mud, a messy but very solid structure as large as a few yards wide and several hundred yards long. Rather inconspicuous dams are more common in our range. A beaver colony may maintain its dam and pond for years, adding new poles and puddling fresh mud (by foot agitation) into the interstices.

Most beaver foods are on land; the adaptation to water is for safety’s sake. The pond is a large foraging base on which few predators are nimble. In much of beaver range, pond ice in winter walls them off from predators. Living quarters, in streambank burrows or mid-pond lodge constructions, are above the waterline, but their entrances are all below it, as are the winter food stores—hundreds of poles cut and hauled into the pond during summer, now submerged by waterlogging. Cottonwood, willows, and aspen are favorites. Beavers can chew bark off the poles underwater without drowning, thanks to watertight closures right behind their incisors and at their epiglottis. They maintain breathing space just under the ice by letting a little water out through the dam. They are well insulated by a thick fat layer just under the skin, plus an air layer just above it, deadened by fine underfur and sealed in by a well-greased outer layer of guard hairs.

The typical beaver lodge or burrow houses a pair, their young, and their yearlings. Two-year-olds must disperse in search of new watersheds, where they pair up, commonly for life, and found new lodges. While searching, they may be found far from suitable streams.

When beavers dammed most of the small streams in a watershed, as they once did throughout much of the West, they stabilized river flow more thoroughly, subtly, and effectively than concrete dams are able to do today. Beaver ponds also have dramatic local effects. First off, they drown a lot of trees. Eventually, if maintained by successive generations, they may fill up with silt, becoming first a marsh and later a level meadow with a stream meandering through it. Such parks well below treeline are abundant and much appreciated in the Rockies, but less common in our range.

Beavers were originally almost ubiquitous in the United States and Canada, aside from desert and tundra. Many tribes considered beavers kin to humans, showing them respect in lore and ritual, while also hunting them for fur and meat. Europeans, in contrast, trapped Eurasian beavers (C. fiber) nearly to extinction just to obtain a musky glandular secretion used as a perfume base. There was a busy trade in this castoreum for centuries before the beaver hat craze hit Europe in the late 1700s and the demand for dead beavers skyrocketed, not letting up until the supply of American beavers became scarce around 1840. Beaver pelt profits provided the main impetus for westward exploration and territorial expansion, including the Louisiana Purchase.

Changing fashions dropped beaver far below carnivore furs in value. Populations recovered about as much as they can, reaching even into central Seattle and Portland, but will never foreseeably regain their natural level because so much beaver habitat has been lost, and the beaver’s considerable ability to rebuild it is not easily tolerated by an agricultural economy.

If we judge the charisma of fauna by the number of geographic names, then beavers rank third in the United States, after bears and deer.

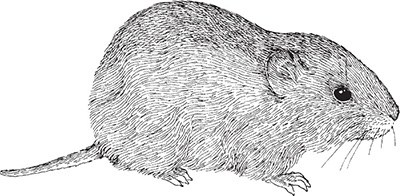

Peromyscus maniculatus (per-o-miss-cus: boot mouse; ma-nic-you-lay-tus: tiny-handed). 3½ in. + 3- to 4-in. tail (length ratio near 1:1); brown to (juveniles) blue-gray above, pure white below including white feet and bicolored, often white-tipped tail; ears large, thin, fully exposed; eyes large. Ubiquitous; nocturnal. Cricetidae.

Deer mouse

The deer mouse is far and away the most widespread and numerous mammal on the continent. Not shy of people, it makes itself at home in forest cabins, farmhouses, and many city houses in the Northwest. It remains less urbanized than the house mouse, Mus musculus, which spread from Europe to cities worldwide together with its relatives the black rat and Norway rat. (Those three invasive urbanites are easily distinguished from our native mice, rats, and voles by their scaly, hairless tails.)

The deer mouse builds a cute but putrid nest out of whatever material is handiest—kleenex, insulation, underwear, moss, or lichens—in a protected place such as a drawer or hollow log. In winter it is active on top of the snow. Omnivorous, it favors larvae in the spring and seeds and berries in the fall. Such a diverse diet adapts it well to burns and clearcuts; as the forest matures, deer mice are gradually displaced by more specialized fungus-eating voles. After Mt. St. Helens’ 1980 eruption, they were common in the blast zone so soon that they are presumed to have survived the blast in their homes, and to have found food under the ash.

Dear mice carry the hantavirus, whose flu-like symptoms in humans can turn deadly if untreated for a few days. The greatest danger is in dry, dusty cabins with deer mice; people can become infected by breathing mouse-contaminated dust. It’s a good idea to minimize handling deer mice, and to wash your hands promptly and thoroughly if you do handle one. They also carry Lyme disease, but don’t transmit it to humans directly and don’t apparently carry it very much in our region, at least not yet.

Many deer mice in western British Columbia and Washington forests with tails at least 3¾ inches long are now separated as the northwestern deer mouse, P. keeni.

Neotoma cinerea (nee-ah-ta-ma: new cutter; sin-ee-ria: ashen). Also packrat. 8–9 in. + 7-in. tail covered with inch-long fur, hence resembling a squirrel as much as a rat; brown to (juveniles) gray above, whitish below; whiskers long; ears large, thin. Can either run or, if chased, hop like a rabbit. Mainland; patchy in nonalpine sites with rock outcrops or talus; nocturnal. Cricetidae.

Bushy-tailed woodrat

For some strange reason, packrats love to incorporate human-made objects, shiny ones especially, into their nests. Possibly some predators are spooked by old gum wrappers or gold watches, or perhaps the packrat’s craving is purely aesthetic or spiritual. She is likely to be on her way home with a mud pie or a fir cone when she comes across your Swiss Army knife, and she obviously can’t carry both at once, so there may be the appearance of a trade, though not a fair one from your point of view. Packrats have other habits even worse than trading, often driving cabin dwellers to take up arms. They spend all night in the attic, the woodshed, or in the walls noisily dragging materials around—shreds of fiberglass insulation, for example. Or they may mark unoccupied cabins copiously with foul-smelling musk. The males mark rock surfaces with two kinds of smears, one dark and tarry, one calcareous white and crusty.

Our common species, the bushy-tailed, is an active trader. It nests in crevices of trees, talus, cliff, mine, or cabin, and sometimes assembles piles of sticks to cache food in. In caves in arid climates, packrat nests and stick piles can last for millennia, held together and perhaps preserved by rock-hard calcareous deposits of dried urine, enabling paleobotanists to study vegetation shifts as far back as the last ice age. Bushy-tailed woodrat middens are studied at Yellowstone.

Phenacomys intermedius (fen-ack-o-mis: impostor mouse). 4¼ in. + 1⅜-in. tail (length ratio 3:1); gray-brown above, paler beneath; tail distinctly bicolored; feet white, even on top. Sporadic, mainly subalpine. Cricetidae.

Heather vole

Heather vole’s winter latrine exposed by snowmelt.

The heather vole lives around the low heath shrub community—heathers, subalpine blueberries, kinnickinnick, and manzanita. You may spot a heather vole’s nest shortly after snowmelt: a 6- to 8-inch ball of shredded lichens, moss, and grass, typically not far from a big heap of rust-colored dung pellets. Both the winter nest and the dung heap were in a snow burrow on the soil surface. The summer nest is underground.

Sometimes called meadow mice, voles are casually distinguished from mice by smaller, even inconspicuous, ears and eyes. Taxonomists differ over whether to separate them from our native mice at the family or the subfamily level.

Microtus oregoni (my-cro-tus: small ear). 4½ in. + 1⅜-in. tail (length ratio 3:1); gray-brown fur exceptionally short, dense. W-side forests, clearcuts, dry meadows, and deciduous woods; CasR, CoastR, OlyM. Cricetidae.

Our smallest vole stays within an inch one way or the other of the ground surface, either burrowing shallowly in loose dirt or plowing little runways through turf, under logs, or inside rotten logs. This offers some protection from hawks, but not from weasels. Creeping voles maintain sparse populations in forests, ready to multiply rapidly, along with grasses and herbs, after a disturbance.

Microtus longicaudus (lon-ji-caw-dus: long tail). 4¾ in. + 3-in. tail (length ratio 3:2); ears barely protruding; fur gray-grizzled, feet pale, tail bicolored. Brushy streamsides, clearcuts, etc.; mainland.

Long-tailed vole

Voles of this large genus, related to arctic lemmings, are known for drastic population swings on a three- or four-year cycle, with each species synchronized over much or all of its range. Mysterious hormonal or behavioral mechanisms, rather than either starvation nor predation, seem to curb the population explosions somewhat short of mass starvation—though not always in time to prevent serious damage to seed or grain crops. The Northwest’s most notorious vole “plagues” have been of Microtus montanus in Klamath and Deschutes Counties.

Microtus townsendii (town-zend-ee-eye: for John Kirk Townsend, p. 350). 5½ in. + 2¼-in. tail (length ratio a little over 2:1); ears distinctly protruding. Moist to marshy meadows at all elevs w of CasCr, including VI but just a short way into mainland sw BC.

Townsend’s vole

This large vole feeds on the succulent stem-bases and root-crowns of lush sedge and grass meadows—a habitat also favored by northern harriers, which feed heavily on the succulent Townsend’s vole. The voles make extensive runway complexes through the grass, swim well, and burrow to make their homes, often with underwater entrances.

Microtus richardsoni (richard-so-nigh: for Sir John Richardson, p. 500). Also water rat. 6½ in. + 3-in. tail (length ratio 2:1); fur long and coarse, reddish dark brown above, paler beneath. In and near CasR and CoastM bogs, streams and lakes.

Water vole

You might think of our largest vole as a small muskrat, except that it goes into the water for refuge, rarely for forage. It dines on our favorite lush wildflowers—lupine, valerian, glacier lilies, and such—eschewing grasses and sedges. In winter it digs up bulbs and root crowns of the same flowers, or eats buds and bark of willows and heathers, while tunneling around under the snow. Look for mud runways running straight to the water’s edge from its burrow entrances, which are up to 5 inches across.

Myodes spp. (my-a-deez: mouse-like). Also Clethrionomys spp. 4 in. + 1¾-in. tail; gray-brown with distinct rust-red band down length of back; tail bicolored similarly; active day or night. Coniferous forests. Cricetidae.

Southern red-backed vole

Southern red-backed vole, M. gapperi (gap-per-eye: for Gapper). WA and BC.

Western red-backed vole

Western red-backed vole, M. californicus (ox-i-den-tay-lis: western). OR or rarely sw WA.

Red-backed voles should be respected as gourmets, since they dine largely on underground-fruiting fungi—which few of us are aware of except when, as “truffles,” they are imported from France or Italy at $300 a pound. It’s no accident that truffles are uniquely fragrant, delicious, and nutritious. These fungi have no way of disseminating their spores other than by attracting animals to dig them up, eat them, excrete the undigested spores elsewhere, and preferably thrive on them over countless generations. Many of our forest rodents evolved as avid participants in this scheme, but none are more dependent than red-backed voles. Since the fungi stop fruiting if their conifer associates die, red-backed voles disappear after a clearcut or destructive burn. They can’t switch from fungi to fibrous vegetation because their molars have lost the ability to keep growing throughout life to replace unlimited wear and tear. Lifelong growth characterizes rodent incisors, and also the molars in some species such as the creeping vole, enabling the latter to switch to grasses and flourish in clearcuts.

Arborimus longicaudus (ar-bor-im-us: tree mouse; lon-ji-caw-dus: long tail). Also Phenacomys longicaudus. 4¼ in. + 3-in. tail (length ratio much less than 2:1); back light cinnamon, belly white with gray underfur; ears concealed, hairless; claws sharp, strongly curved. High in conifers, in OR. Cricetidae.

The rarely seen red tree vole is one of the strikingly few animals that subsist on our most plentiful “green vegetable,” conifer needles. It is not an easy life. Tree vole populations are limited and spotty, despite the ubiquity of the resource and the lack of competition for it. The hardship of eking nutrition out of needles is evidenced by lengthy gestation (28 days), small litters (of one to three), and slow infant development in tree voles, compared to similar-sized rodents. Just a day or two after giving birth, the female is receptive again. The rest of the month she aggressively rebuffs males, and the sexes nest separately.

The vole ventures from its nest for only about one hour per night. Gathering fir branchlets doesn’t take long; the hard work (done back in the nest) is nibbling and digesting them. Tooth wear may be the main limit on lifespan. The vole can eat only the needle margins, leaving the two resin ducts whose pitchy contents would overwhelm its digestive system. A fraction of the resulting debris (100 needles may be consumed per hour) is used to line the nest, an airy edifice enlarged over the generations to include several rooms and escape tunnels. The only known escape tactic appears to consist of a leap and free fall from the conifer canopy, with legs spread wide like a flying squirrel prototype. The vole almost always lands on its feet.

Researchers find tree voles hard to get to and impossible to count: you can’t bait them into a trap because the only thing they eat is always copiously available. Still, it’s clear that they prefer old-growth. Young forests are short on thick limbs for nests, and on the massive moss growths (p. 328) that intercept fog and retain liquid water even through dry spells. Tree voles rely on these for their water.

Ondatra zibethicus (ahn-dat-ra: Huron tribe’s name for muskrat; zi-beth-ic-us: civet- or musk-bearing). 9–13 in. + 7- to 12-in. tail; tail scaly, pointed, flattened vertically; fur dark glossy brown, paler on belly, nearly white on throat; eyes and ears small; toes long, clawed, slightly webbed; voice an infrequent squeak. In or near slow-moving water up to mid elevs. Cricetidae.

Muskrat

We are tempted to think of the muskrat as an undersized beaver, but its anatomy unmasks it as an oversized vole. Leading similar aquatic lives, beavers and muskrats grow similar fur, which was historically trapped, traded, marketed, and worn in similar ways. (The guard hairs are removed, leaving the dense, glossy underfur.) Several million muskrats are still trapped annually—more individuals and more dollar value than any other US furbearer. In the South, the meat also finds a market as “marsh rabbit.”

They are smaller than beavers—half the length and rarely a tenth the weight—and their teeth and jaws aren’t robust enough to cut wood, so they build no dams or ponds. Soft vegetation like cattails, rushes, and water-lilies makes up the bulk of their diets, their lodges, and the rafts they build to picnic on. They stray from the vegetarianism typical of the vole family, eating tadpoles, mussels, snails, or crayfish. Their interesting mouths remain shut to water while the incisors, out front, munch away at succulent stems underwater. They can take a big enough breath in a few seconds to last them 15 minutes underwater. Both sexes, especially when breeding, secrete musk on scent posts made of small grass cuttings. Neatly clipped sedge and cattail stems floating at marsh edges are a sign of muskrats. East of here, many muskrats build domed lodges, but in our area the norm is a burrow in a mud bank. The entrances, usually underwater, lead upslope via tunnels to chambers above the water line.

The South American nutria, Myocastor coypus, a similar rodent about twice as big, is occasionally seen in the lowlands, especially in Oregon. Nutria fur farms were established in the early 1930s in response to an aggressive, deceptive promotion campaign. When profits failed to materialize, many hard-up farmers just turned their rodent herds loose illegally. Nutria locally threaten some crops and native competitors, particularly muskrats.

Zapus spp. (zay-pus: big foot). 4 in. + 5- to 6-in. tail (longer than body); sharply two-toned, with back dark brown to black, sides paler; belly buff white; hind feet several times longer than forefeet; ears small. Thickets and meadows near streams, mainland, May to September. Dipodidae.

Pacific jumping mouse, Z. trinotatus (try-no-tay-tus: 3-striped back). Sides washed with orange. Mainly w-side.

Western jumping mouse

Western jumping mouse

Western jumping mouse, Z. princeps (prin-seps: a chief, perhaps ironically). Sides washed with yellow. Mainly e-side.

The jumping mouse can run on all fours, but it prefers to hop along in tiny hops, or to swim. If you flush one it’s likely to zigzag off in great bounding leaps of 4 or 5 feet. This unique gait gives you a good chance of recognizing them, even though they’re mainly nocturnal. The oversized feet are for power, and the long tail for stability: jumping mice that have lost or broken their tails tumble head-over-heels when they land from long jumps. While none of our other mice or voles hibernate at all, this one hibernates deeply for more than half the year. It eats relatively rich food—grains, berries, insects, and tiny truffles that grow on maple roots.

Erethizon dorsatum (er-a-thigh-zon: angering; dor-say-tum: back). 28–35 in. long, including 9-in. tapered tail; large girth; blackish with long coarse yellow-tinged guard-hairs and long whitish quills visible mainly on the rear half; incisors orange. Mainland, mainly e of CasCr. Erethizontidae.

Porcupine

Porcupines’ bristling defenses permit them to be slow, unwary, and too blind to obtain a driver’s license. This is both good and bad news, for you. Though they’re mainly nocturnal, you stand a good chance of seeing one some morning or evening, and possibly of hearing its low murmuring song. And you stand a good chance of having your equipment eaten by one during the night. Porcupines crave the salts in sweat and animal fat, and don’t mind eating boot-leather, rubber, wood, nylon, or for that matter brake hoses, tires, or electrical insulation, to get them. (Marmots also consume car parts occasionally.) When camping in east-side valleys, always sleep by your boots, and make your packstraps hard to get at, too. Fair warning.

Quills and spines are modified hairs that have evolved separately in many kinds of rodents, including two separate families both called porcupines. On American porcupines they reach their most effective form: hollow, only loosely attached at the base, and minutely, multiply barbed at the tip. The barbs engage instantly with enough grab to detach the quill from the porcupine; quickly swell in the heat and moisture of flesh; and work their way farther in (as fast as one inch per hour) with the unavoidable twitchings of the victim’s muscles. Though strictly a defensive weapon, quills can occasionally kill, either by perforating vital organs or by starving a poor beast that gets a noseful. More often they work their way through muscle and out the other side without causing infection, since they have an antibiotic greasy coating.

So, just maintain a modest safe distance while the porky, most likely, retreats up a tree. “Throwing their quills” is a myth; in fact, they just thrash their tails, whose range sometimes takes people by surprise.

Since quills are their only defense, porcupines have to be born fully quilled and active in order to survive infancy in good numbers. This requires long gestation (seven months) and small litters (one or rarely two). But still, how to get little spikers out of the womb? Answer: the newborn’s soggy quills are soft, but harden in about half an hour as they air-dry. And then again, how to get mama and papa close enough to mate? Or baby close enough to nurse? Solving these problems has given porcupines their Achilles’ heel, or rather, soft underbelly. With a quill-less underside including the tail, a porcupine can safely mate with her tail scrupulously drawn up over her back. (They mate in late autumn, but are otherwise solitary.) The soft underbelly actually has very tough skin, to hold up through months of dragging up and down tree bark. Genitalia of both sexes are protected from abrasion by withdrawing entirely behind a membrane. This makes it hard to tell the sexes apart.

If it weren’t for that unarmed belly, predators would have no place to begin eating. And predators there are, mainly fishers and cougars; rarely coyotes, bobcats, and even great horned owls. The soft underbelly is safe as long as porky is alive enough to stay right side up. Fishers attack the head. Follow their example, with a heavy stick, if you ever find yourself lost and starving and near a porcupine. Some states protect porcupines on the grounds that they are easy edible prey for unarmed humans lost in the woods. They are not choice fare. They were sometimes eaten by Indians, who also turned the quills into an elegant art medium on clothing and baskets

Porcupines eat leaves, new twigs, and catkins in summer, and tree cambium, preferably of pines, in winter. They select cambium near the top of the tree, where it is sweetest. Bright patches of stripped bark high up in pines are a sign of porcupine. When they kill a tree’s top by girdling it, the tree turns a branch upward to form a new main trunk, leaving the tree kinked and diminished in lumber value. So foresters are alarmed at the increasing porcupine populations that resulted mainly from human persecution of predators.

Like the red tree vole, the porcupine reveals the nutritional stress of subsisting on this all-you-can-eat cafeteria. Porcupines inexorably lose weight in winter, even while keeping their big guts stuffed with bark. In summer when trees offer tender new foliage, they defend it with toxically high potassium levels. For the porcupine kidney to keep up with the task of eliminating potassium, the porcupine is driven to find low-acid, low-potassium sources of sodium. Your sweaty boots and packstraps fit the bill, as do the coolant hoses and wire insulation it can find at the trailhead. For the same reason deer and elk eat the mud around soda springs, and mountain goats go after human urine.

Thomomys spp. (tho-mo-miss: heap mouse). 5½ in. + a scarcely hairy 2½-in. tail; highly variable gray-brown tending to match the local soil; front claws very long, eyes and ears very small, incisors large and always showing. Open areas with loose soil. Geomyidae.

Mazama pocket gopher, T. mazama (ma-za-ma: the Crater Lake volcano). OlyM and OR CasR.

Northern pocket gopher

Northern pocket gopher, T. talpoides (tal-poy-deez: mole-like). CasR of WA and BC.

Pocket gophers spend their lives underground, and have much in common with moles: powerful front claws, heavy shoulders, small weak eyes, small hips for turning around in tight spaces, and short hair with reversible “grain” for backing up. But moles live on worms and grubs, and gophers are herbivores. They can suck a plant underground before your very eyes, making hardly a dent on the surface. They get enough moisture from their food that they don’t even go to water to drink. In fact, only two occasions always draw them into the open air. One is mating, in spring. That takes only a few minutes, and draws out only the males. Afterward, they return to mutually hostile solitude, plugging up burrow openings behind them. The other is the eviction of young gophers from their mothers’ burrows.

Gopher “esker” exposed by snowmelt.

Gophers sustain their populations on just one small litter per year, attesting to the safety of life underground. Badgers and gopher snakes are well equipped to take gophers, but rarely venture very far into our range. At the same time, the low reproduction rate signals severe energy costs. Burrowing ten feet takes about 1000 times more energy than walking ten feet. To power that, gophers eat roots and tubers, the most energy-rich part of a meadow.

Our T. mazama does go out on occasion, mainly at night. Also, any gopher that lives where it gets snowy may, without exactly going out, eat aboveground foods like bark and twigs by tunneling around through the snow. In spring (July or so in the high country) you find gopher eskers—sinuous ridgelets about 3 inches wide of dirt and gravel that came to rest on the ground during snowmelt. Shortly before snowmelt, the gopher resumed burrowing, and used the abandoned snow tunnels as dumps for newly excavated dirt. Gophers’ summer throw mounds are fan-shaped.

When Mt. St. Helens blew, some gophers survived in their burrows under plants that got buried in ash. When they dug out to the surface afterward, they churned old soil into the new ash, helping new plant seedlings contact mycorrhizal spores that were essential to plant survival in the nitrogen-poor ash.

A pocket gopher’s pocket is a cheek pouch used, like a squirrel’s, to carry food. Unlike a squirrel’s, it opens to the outside. Fur-lined and dry, it turns inside out for emptying and cleaning. The big protruding “gopher teeth” are used for digging. The lips close behind them to keep out the dirt.

Marmota spp. (mar-moe-ta: their French name). Also rockchuck, whistle pig. Heavy-bodied, thick-furred, large rodents of mountain meadows and talus, known for their piercing whistles. Sciuridae.

Hoary marmot

Hoary marmot, M. caligata (cali-gay-ta: wearing boots). 20 in. long + 9-in. tail; grizzled gray-brown, with black feet and pale belly and bridge of nose. Alp/subalpine, WA and BC CasR and CoastM.

Olympic marmot, M. olympus Like hoary marmot but face and feet markings less contrasty; back often yellowish by late summer, perhaps bleached by urine-soaked burrow walls. Alp/subalpine, OlyM.

Vancouver marmot, M. vancouverensis. 16 in. + 8-in. tail; becoming rich dark brown after the midseason molt; white nose and chest. Alp/subalpine on VI; rare (endangered).

Yellow-bellied marmot

Yellow-bellied marmot, M. flaviventris (flay-vi-ven-tris: yellow belly). 16 in. long + 6½-in. tail; yellowish brown, often gray-grizzled, with yellower throat and belly; feet darker. From CasCr e, mainly lowlands, but sometimes subalpine (as it is in Rockies and CA).

It’s hard to feel you’re really in the high country until you’ve been announced by a marmot, with a sudden shrill shriek. If you hear no shrieks in what looks like good marmot habitat, and maybe even has some marmot burrows with their 4-foot porches, it may be because the day got too warm for them and they’re all taking a siesta below ground. The shriek (done with the vocal chords and thus not a true whistle) is a warning that may send several other marmots lumping along to their various burrows. The shrieker probably moved to safety near a burrow entrance before deciding whether to shriek. The others then look around, perhaps standing up like big milk bottles, to appraise the threat level. From the inflection of the shriek they know whether to look for the predator in the sky or on the ground. In your case, they may after a while become nearly oblivious to you, or even quite forward and interested in your goods. You may get to watch them scuffle, box, and tumble, or hear more of their vocabulary of grunts, growls, and chirps. They often greet each other with hugs and kisses—well, mouth-to-mouth, teeth-to-teeth, or nose-to-nose contact, and chewing each other’s faces and necks.

Marmots need their early warning system because they’re slow, and count all the large predators as enemies. They perforate their meadow with dozens of escape burrows. To protect themselves from digging furies—badgers—our yellow-bellied marmots locate many burrows in rockpiles. Our subalpine marmots, with no badgers to worry about, burrow in loose meadow soils. An entire hibernating family can be dug out and eaten by a bear, but that is rare. Coyotes have become the greatest threat overall. People rarely hunt them any more, though in the old days marmots earned high marks for fur, flavor, and fat content in fall. The Tlingit measured wealth in marmot skins.

Squirrels wrote the book on hibernation, and these largest of all squirrels take hibernating seriously indeed. They put on enough fat to constitute as much as half their body weight, and then bed down for more than half the year, the colony snuggling together to conserve heat. Resist the temptation to think of seven-month hibernation as a desperate response to an extreme environment. It is just one strategy that can work here. Other small subalpine grazers like the pika and the water vole stay active beneath the snow at a comfortable constant 32°F, and long-legged browsers forage above the snow, either staying subalpine or migrating downslope. These different wintering strategies align with tastes for different plants, so the grazing species rarely compete directly for one food resource.

Marmots concentrate a year’s worth of eating into a brief green season. The season doesn’t have to be summer. Our three subalpine marmot species keep a winter schedule (hibernating late September to early May) similar to that of yellow-bellied marmots of the high Rockies; but our yellow-bellies, low on the Cascades’ east slope, fatten in April and May and go down for their seven-month slumber in midsummer when the heat dries up spring’s herbs and grasses. Summer torpor is aestivation as opposed to hibernation, but yellow-bellies have never heard of that distinction, and go from one to the other without pause.

Young yellow-bellies mature fast enough to disperse (leave their maternal burrow) at the end of their first or, more often, second summer. With an even shorter active season, subalpine marmots mature slowly, dispersing in their third or fourth summer. Young marmots and adult females alike suffer heavy casualties to winter starvation. Even more than a mother bear, a marmom is hard put to fatten enough for her nursing litter’s hibernation as well as her own; females skip breeding in some years. (This used to be seen as rigid every-other-year breeding, but closer study found it to be variable: dominant, well-fed females commonly breed in consecutive years, but low-ranked females often skip years.) The colony often consists of an alpha ménage à trois surrounded by their young and a few “aunts and uncles” who help out. Most of the marmot tussles you see are youngsters at play. Those that end in a one-sided chase may be colony members evicting outsiders or nudging their own young adults to disperse.

The wild population of Vancouver marmots reached a low of around 35 individuals in 2004. Big human-influenced swings in predator numbers and behavior probably contributed, as did extensive clearcut logging, which created an illusion of extensive new marmot habitat. Colonies seemed to thrive in clearcuts, only to die out when the trees regrew. Since then, several hundred captive-bred Vancouver Island marmots have been released, and are surviving and reproducing. One study found that current colonies may be too small for the predator alarm system to work efficiently. Not only are too many marmots killed, but they spend so much time looking around for predators that they have trouble eating enough to be ready to hibernate.

Olympic marmots are also in decline, especially in the southern half of the park and the northeastern edge. Their decline is blamed on intense predation by the coyotes, which invaded here after wolves were killed off, and are now the marmots’ chief predator.

While climate change didn’t directly cause either of those declines, it’s likely to harm most high-mountain specialists sooner or later. Many subalpine meadows are expected to shift to either forest or steppe vegetation, neither of which offers much marmot forage. However, studies of warming’s effects on marmots to date yield mixed verdicts: shorter snow-free seasons benefit marmots in the Colorado Rockies (by giving them more to eat, sooner) but increase winter mortality in the Yukon. Apparently winter dens there got too cold when the insulating snow cover melted away before plant growth invited the marmots to come out and eat.

Callospermophilus spp. (calo-sper-mah-fil-us: beautiful seed lover). Also copperhead; Spermophilus spp. 7 in. + 4-in. bushy tail; medium gray-brown with 2 dark and 1 light stripes along each flank; head and chest (the “mantle”) tawny to yellow-brown, and not striped. Grass balds, subalpine, and e-side. Sciuridae.

Golden-mantled ground squirrel

Golden-mantled ground squirrel, S. lateralis (lat-er-ay-lis: sides, referring to stripes). In OR.

Cascade golden-mantled ground squirrel, S. saturatus (satch-er-ay-tus: dark). BC CasR, WA.

These ground squirrels occupy some of the same open-forest range as the yellow-pine chipmunk, but may avoid direct competition by being less arboreal and by hibernating for months, fattening grossly in the fall. They eat a smorgasbord of seeds, nuts, leaves, shoots, and fungi. Ground squirrel cheek pouches—the mucus-lined mouth interior that extends nearly to the shoulders—can hold several hundred seeds. Their alarm call is a single sharp whistle, higher-pitched than a marmot’s (and used less often).

A 2009 study split the large genus Spermophilus eight ways. All the North American ground squirrels came away with new names, including three larger, stripeless species found at various grassy margins of our range: Columbian ground squirrel, Urocitellus columbianus, in Okanogan County, Washington, and adjacent British Columbia; Belding’s ground squirrel, U. beldingi, on the east-side Cascades in Oregon; and California ground squirrel, Otospermophilus beecheyi, in grasslands in and near the Coast Range and southern Puget-Willamette Trough. Standing 10 inches tall in their milk-bottle posture, any of these could almost pass for marmots.

Glaucomys sabrinus (glawk-amiss: silvery-gray mouse; sa-bry-nus: of the Severn). 7 in. + 5½-in. tail (broad and flat); large flap of skin stretching from foreleg to hindleg on each side; eyes large; red-brown above, pale gray beneath. Forest. Sciuridae.

Northern flying squirrel

Active in the hours just after dark and before dawn, these pretty squirrels are rarely seen. On a quiet night in the forest, you might hear a soft birdlike chirp and an occasional thump as they land low on a tree trunk. They can’t really fly, but they glide far and very accurately, and land gently, by means of lateral skin flaps, which triple their undersurface. They can maneuver to dodge branches, and almost always land on a trunk and immediately run to the opposite side—a predator-evading dodge that includes a feint of the tail in the opposite direction. Large owls preying on them often pick off and drop the tail, so we sometimes find jettisoned tails on the ground.

Flying squirrels usually nest in old woodpecker holes, and have their young gliding at two months of age, around midsummer. They don’t hibernate, nor do they store great quantities of food for winter. Ours mainly eat truffles (underground-fruiting fungi), sometimes augmented in winter with horsehair lichens, which also insulate their nests. (Intensive fungivory seems unique to Pacific Northwest flying squirrels, and requires at least a small supplement of richer fare, like seeds or nuts.) The truffle / flying squirrel / spotted owl food chain may be a key to spotted owls’ dependence on old growth forest, since truffles abound only in old-growth, especially within thoroughly rotted fallen trees. Logging methods that leave some coarse woody debris and some patches of old trees benefit flying squirrels, red-backed voles, and ecological health overall.

Sabrinus was a river nymph in Roman myth, but the squirrels didn’t get their name for being river nymphets. The type, or first-described specimen, of the species lived by Ontario’s Severn River, which was named after England’s Severn River, originally named Sabrinus by the Romans.

Tamias spp. (tay-me-us: storer). Rich brown with four pale and three dark stripes conspicuous down the back and from nose through eyes to ears. Sciuridae.

Townsend’s chipmunk

Townsend’s chipmunk, T. townsendii (town-zend-ee-eye: for John Kirk Townsend, p. 350). 6 in. + bushy 5-in. tail; pale stripes grayish. Dense forest.

Yellow-pine chipmunk

Yellow-pine chipmunk, T. amoenus (a-me-nus: delightful). 5 in. + bushy 4-in. tail; pale stripes yellowish brown. Open conifer forest and timberline areas; not on VI or in CoastR, rare in OlyM.

These small chipmunks are diurnal, noisy, and locally abundant. Their diverse chips, chirps, poofs, and tisks can be mistaken for bird calls. Townsend’s is often heard without being seen, since it prefers heavy forest cover and is shy. Though sometimes seen together, these two species are more often separated by habitat if not by range; yellow-pine chipmunks require open forest, and tend to be either higher or farther east than Townsend’s.

Our chipmunks are semi-arboreal, nesting either in burrows or up in trees. They forage terrestrially for seeds, berries, a few insects, and, increasingly toward winter, lots of underground fungi. To facilitate food-handling, they have an upright stance (like other squirrels and gophers) that frees the hand-like forefeet. They store huge quantities of food, carrying it to their burrows in cheek pouches. Their winter strategy varies with climate and genetics, but commonly they rely on stored food alone, without fattening up. They pass the winter with a series of torpid bouts at only moderately depressed body temperatures; every four or five days they get up to excrete and eat from stores in the burrow. You may hear their chatter even in midwinter, and on milder days at lower elevations they are likely to go out and forage. The young, though born naked, blind, and helpless, mature fast enough to disperse and make their own nests for their first winter.

Tamiasciurus douglasii (tay-me-a-sigh-oo-rus: chipmunk squirrel; da-glass-ee-eye: for David Douglas, p. 56). Also chickaree. 7 in. + bushy 5-in. tail; red-tinged gray-brown above; eye-ring and underside orange, with a black line separating the upper and lower colors. Forest. Sciuridae.

Douglas’s squirrel

Noisy sputterings and scoldings from the tree canopy call our attention to this creature that, like other tree squirrels, can afford to be less shy and nocturnal than most mammals thanks to the escape offered by trees. Scolding lets all the neighborhood squirrels know there’s a possibly dangerous animal nearby, but once they know about you they don’t seem to consider you much of a threat. There are predators that take squirrels quite easily—martens, goshawks, large owls—but apparently they were never common enough to put a dent in the squirrel population, and are scarcer than ever today, in retreat from civilization. Unlike squirrels.

The similar red squirrel, T. hudsonicus, replaces Douglas’s on Vancouver Island and in the eastern British Columbia Cascades (but not Coast Mountains) and Okanogan County, Washington; it is common eastward across the continent. Its dorsal color is slightly redder or darker, while its underside and eye-ring are whitish.

Sometimes in late summer and fall we know Douglas’s squirrel by the repeated thud of green true-fir cones hitting the ground. Since fir cones are designed to open and drop their seeds while still on the tree, closed cones you see on the ground are likely a squirrel’s harvest. The squirrel runs around in the branches nipping off cones, twelve per minute on Douglas-fir or up to thirty per minute for some smaller cones; then it runs around on the ground carrying them off to cold storage. True-fir cones are too heavy to drag or carry, so it gnaws away just enough of the outside of the cone to lighten it to a draggable weight, while leaving the seeds still well sealed in. Some day, it will carry the cones back up to a habitual feeding limb and tear them apart, eating the seeds and dropping the cone scales and cores in a heap we call a midden. Either the center of a midden or a hole dug in a streambank can be used to store cones for one to three years. The cool, dark, moist conditions keep the cone from opening and losing its seeds and also, incidentally, keep the seeds viable. Foresters learned to rob middens, and squirrels became the chief suppliers of conifer seed to Northwest nurseries by 1965. This scam is in decline now that nurseries want to pick particular trees for breeding.

Mushrooms and truffles, which must be dried to keep well, are festooned in twig crotches all over a conifer, and later moved to a dry cache such as a tree hollow. With such an ambitious food-storage industry, this squirrel has no need to hibernate. For the winter, it moves from a twig and cedar-bark nest on a limb to a better-insulated spot, usually an old woodpecker hole. This-year’s young winter in their parents’ nest (unlike smaller chipmunks) since they need most of a year to mature.

The proportion of all conifer seeds that are consumed by rodents, birds, and insects is huge, exceeding 99 percent in some poor cone crop years. Foresters have long regarded seed eaters as enemies. But the proportion of conifer seeds that germinate and grow is infinitesimal anyway, and of those, the percentage that were able to succeed because they were harvested, moved, buried, and then neglected is significant. Trees coevolved with seed eaters in this relationship, and may depend on it (see p. 84). Additionally, all conifers are dependent on mycorrhizal fungi, many of which depend in turn on these same rodents to disseminate their spores. Conifers limit squirrel populations by synchronizing their heavy cone crop years. A few poor cone crop years bring squirrel numbers down, and then the trees produce a bumper crop with way more seeds than the reduced population can eat.

Sciurus griseus (sigh-oo-rus: their Greek name, from “shade tail;” gris-ee-us: gray). 12 in. + very bushy 10½-in. tail; gray frosted with silver-white hair tips; belly white; ears reddish. Dry, open forest in OR; rare in WA, in Klickitat, Chelan, and Okanogan Counties. Sciuridae.

Western gray squirrel

Scarcer than Douglas’s squirrels and rarely vocal or bold, these gray beauties are infrequently seen or heard. With their huge tails, they are gracefully athletic to watch. Large size and good meat make them popular game. They are protected, as a threatened species, in Washington, but still hunted in Oregon even though they are declining. They live around oaks and pines, as they need acorns or pine nuts to augment their diet of truffles.

Members of six families in the order Carnivora are described below. All six are household words: dogs, cats, raccoons, bears, skunks, and weasels. The order also includes seals and walruses.

Canis latrans (cay-niss: dog; lay-trenz: barking). 32 in. + bushy 14-in. tail; shoulder height 16–20 in.; medium sized, pointy-faced dog with erect, pointed ears; blend of tan, gray, brown, or sometimes mostly black; runs with tail down or horizontal. Ubiquitous except on VI and CoastM. Canidae.

Coyote

In pioneer days, wolves ruled the forests, leaving coyotes to range over steppes, brushy mountains, and prairies. Then during the 19th century, guns and traps tipped the scales in favor of coyotes by targeting the bigger predators—cougars and grizzlies as well as wolves. Where the big predators were eliminated, coyotes, bobcats, and eagles inherited the brunt of predator-hatred, even though they are too small to significantly limit deer or sheep numbers. Coyotes are America’s most bountied, poisoned, and targeted predator, yet they uncannily persist, increase, and spread. Returning wolves may halt that trend, but reports are mixed as to whether that is happening yet at Yellowstone.

More often than you’ll see coyotes, you’ll hear them howling at night. You can guess that hair-filled scats in the middle of the trail are likely theirs, especially when placed smack dab on a stump, hummock, footlog over a creek, in an intersection, on a ridgetop, or any combination of the above. Coyote feces and urine are not mere “waste,” like yours, but more like graffiti signatures full of olfactory data that later canine passers-by, even other species, can read. In Chinook myth, Coyote consulted his dung as an oracle! The male canine habit of fiercely scratching the ground after defecating deposits scents from glands between the toes. The long noses in the dog family really are “the better to smell you with, my dear,” as the large olfactory chamber is loaded with scent receptors. Coyotes can detect the passage of other animals a mile or two away, or days earlier. They read scent posts to learn each other’s condition and activities. Mates scent-mark together on the same spot. Territory is not a primary function of marking, as coyotes aren’t particularly territorial.

When you’re trying to identify scats, being full of hair easily distinguishes predator scats from those of herbivores or kibble-fed canids, and size separates coyotes from, say, martens. Further characteristics can tentatively identify the scatmonger; study these in Wildlife of the Pacific Northwest or other guides. Scat ID is trickier than you might expect: in one study, biologists collected 404 predator scats in Olympic National Park. (They were finding out who is eating Olympic marmots. Answer: mainly coyotes.) They field-identified the scats, then confirmed the ID using DNA. Their field accuracy rate was only 63 percent. Given that there were only three candidates—cougar, bobcat, and coyote—random guessing would have yielded 33 percent.

As for their spooky nocturnal cacophony, most people hearing it feel that it, too, conveys something above and beyond mere location—though helping a family group relocate each other is its best-understood function. Often it’s hard to tell how many coyotes we are listening to; the Modoc used to say it’s always just one, sounding like many. Coyote choruses mix up long howls with numerous yips; wolves howl without yipping.

Though preferring small mammals and birds, coyotes also eat grasshoppers, berries, mushrooms, and scavenged carrion. Stalking mice, they patiently “point” like a bird-dog, then pounce like a fox. Against hares they use the fastest running speed of any American predator. Though they commonly try to pick off fawns or elk calves, they hunt adult deer only rarely, locally, and usually in later winter when they gain an advantage from crusted snow as well as the winter-weakened condition of the prey. Usually they hunt alone or pair up, one mate perhaps decoying or flushing prey to where the other lurks. An unwitting badger, eagle, or raven may be briefly employed as a partner.

Pairs bond for many years, and display apparent affection and loyalty. To say they mate for life would be about as euphemistic as saying that Americans do. In years when coyotes are abundant and rodents are unusually scarce in a given area, as many as 85 percent of the mature females there may fail to go into heat, and those who do mate will bear smaller litters than usual. On the other hand, they reproduce like crazy when their own populations are depleted. Some coyotes remain with their parents as yearlings, helping to raise the new litter. Thus the most typical pack is a family, but coyotes vary, sometimes forming larger groups and sometimes remaining solitary or in pairs.

The fierce antagonism of wolf packs toward outsiders (including coyotes) has been key to maintaining wolves and coyotes as distinct species. Wolves, coyotes, jackals, and domestic dogs are all interfertile and beget fertile offspring, yet they are dramatically divergent, physically and behaviorally. The separation of wolves and coyotes broke down (producing “red wolves” and very large coyotes) in parts of the East where coyotes moved in after wolves were nearly extirpated; the tiny, stressed remnant wolf population presumably had no experience of coyotes, and allowed some interbreeding.

Coyote the Trickster is a ubiquitous, complicated figure in Indian mythologies, a devious intelligence undermined by downright humanoid carelessness, greed, conniving lust, and vulgarity. In some myths, Coyote exemplifies the bad, greedy ways of hunting that destroyed a long-gone Eden-like abundance. In others, he brought the poor starving people rituals and techniques they needed, like catching salmon. Each of those tells half the story that anthropologists reconstruct: the first people in North America found an Eden-like abundance; eventually their population in some regions, like the Northwest Coast, reached a saturation point for simple hunting and foraging, and the people had to learn to store salmon and roots. Some tribes, on learning about Jesus, saw Him as the white man’s Coyote since He came to Earth to improve people’s lot.

In other myths Coyote is the Creator. No wonder the world doesn’t always work perfectly.

Canis lupus (loop-us: the Roman name). 52 in. + bushy 18-in. tail; shoulder height 26–34 in.; large gray to tan dog with massive (not pointy) muzzle, long legs; ears erect, tips rounded; blend of tan, gray, brown, or sometimes mostly black or rarely white; thicker-furred in winter; runs with tail down or horizontal. North CasR, VI, CoastM; expected elsewhere. Canidae.

Gray wolf

Wolf, resurgent! Packs now roam the eastern North Cascades and the Wallowas, after several decades of absence from Washington and Oregon, and are likely to continue to spread in the Cascades. Vancouver Island’s wolves—a paler subspecies—rebounded from a point so low that some people called them extinct to abundance sufficient to make them the chief predator of the endangered Vancouver marmot. The Coast Mountains supported wolves all along, though not as abundantly as central and northern British Columbia. Today’s Oregon and Washington wolves descend from British Columbia wolves, and some opponents point out that they are thus nonnative. Their degree of genetic divergence from wolves that lived here in the past is not likely very significant. Certainly they are a native species, whose reinsertion into our food web should have far-ranging ecological benefits.

Wolves and coyotes are very closely related, and interfertile. What separates them reproductively, keeping their genetic lineages distinct in most areas is a trait called interference competition, which means that wolves attack every coyote they run across, often killing them.

Within a wolf pack, aggression is infrequent. A picture of ceaseless vicious competition over alpha status originated from observations of captive wolves thrust into pens together. Wolves in the wild were so wary of people that there was no way to observe their normal lives. David Mech overcame that obstacle by spending 13 summers on an arctic island with wolves that had never encountered humans and were unwary. His conclusion: a pack is a family. Rather than an “alpha female” and “alpha male,” we might speak of the “mom and dad.” The kids wouldn’t think of challenging Dad’s alpha status. Medium-sized packs include two or three years of offspring. Some add a male adoptee; occasionally a daughter and the adoptee become a second breeding pair within the pack.

Young wolves may disperse as young as ten months, when they are full-grown, or as late as three years, when their hormone levels begin to peak, and drive them to reproduce. They have several paths to breeding: adoption; replacing a breeder who has died; usurping one who is still alive; or most often pairing with another disperser to found a new pack on a new territory. Those paths can all lead to deadly aggression, as can efforts of neighboring packs to expand their territories when food is scarce.

Hunting as a pack (typically three to five mature pack members) facilitates taking prey as large as elk, moose, or bison. Large prey are dangerous, but a single wolf can actually take a moose. Economic analysis, in terms of meat per capita, suggests that the pack advantage may center not on the hunt but on holding ravens at bay afterward until most meat is consumed.

When the saber-tooth tigers and other Pleistocene megapredators went extinct, leaving only wolves, grizzlies, and humans to prey on the large herbivores, it destabilized North American ecology. Since grizzlies rarely prey on large herbivores, regional extirpations of wolves throw things way out of balance, with no regular predator at all for the large species.

In the 19th century, Euro-Americans despised and feared wolves. Some people still feel that way, but in much of the media wolves have gone from cruel to cuddly. Both views are exaggerations. Wolves are wild carnivores. Statistically, they rarely attack people but, like black bears, they can do so, and are more likely to if they are habituated to people, or if they have rabies. Wolf-dog hybrids and wolves that have been raised by people are especially dangerous.

Some time during the last ice age—probably many times, in many places—some wolves began hanging around humans to scavenge food scraps. At some villages this strategy fed them well, and their descendants thrived, or the mellower-tempered ones did while aggressive ones were driven away or killed. Over the generations, humans came to like these self-selected dogs while often finding ways to exploit them—for meat, or wool, or to haul loads. At some point, dogs began to participate in a hormonal response known for strengthening trust and bonding between human mothers and infants: if a dog and its owner gaze into each other’s eyes, oxytocin levels rise in both of them. This doesn’t happen in wolves, even ones raised by humans. The wolves that stayed wild back then continued to evolve, so that modern wolves are not as closely related to dogs as ancient wolves were. Dogs are thus not wolves, even thought they are officially Canis lupus. (Linnaeus named dogs Canis familiaris, but current taxonomists don’t regard domestication as speciation.)

Vulpes vulpes (vul-peez: the Roman name). Also V. fulva. 24 in. + 15-in. tail; shoulder height 16 in. (terrier size); various colors, with black legs and ear tips, white belly and tip of tail. Mainland, infrequent; the native subspecies are rare, subalpine, found around our biggest volcanoes. Canidae.

Red fox

Foxes are little seen here—nocturnal, shy, elusive, and alert. They can bark and squall, but rarely make a concert of it. Their tracks and scats are hard to tell from small coyote ones, and their dens are most often other animals’ work taken over without distinctive remodeling.