Chapter

Two

The Indy Maru

While the war raged across the sea, the USS Indianapolis was being refitted with more sophisticated radar and gunnery equipment at Mare Island, San Francisco. My first duties as a Marine were on what we called Goat Island in the San Francisco area, guarding Navy and Marine personnel confined to the brig. Several weeks passed before I had received my orders to board the USS Indianapolis, affectionately nicknamed the Indy Maru. Most ships were given nicknames, and though it is not known how the Indianapolis got hers, it is interesting to note that maru is the Japanese word for “ship.”1

I’ll never forget that exhilarating day we first sailed out of Mare Island in the early part of 1944. The reality that I was off to war really began to sink in. I could not possibly be aware of the demonstration of divine providence that would see me through it all.

I was naïvely excited as our skipper, Capt. E. R. Johnson, set course for our first destination: Pearl Harbor. There we were to “pick up our flag”—Navy talk for picking up an admiral, ours being Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, commander of the Fifth Fleet. I can still remember the first time I saw Admiral Spruance walking on the forward deck of the Indianapolis. He would do it often, and for long periods of time almost every day. I can only imagine the stress he had to endure given the enormity of his responsibilities. He was an impressive man who easily earned respect. He gave his young sailors and Marines confidence as we prepared for battle. We were all proud to serve under him.

Combat Aboard Ship

My first combat experience was at Kwajalein and Eniwetok in the Marshall Island chain (see map in chapter 7). That action was primarily a clean-up operation, destroying any remaining installations through heavy bombardment. Our ultimate sights, however, were on Guam, Saipan, and Tinian, crucial islands for providing a staging area for our new Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers to be able to attack the mainland of Japan.

From the Marshalls we moved on to attack the Western Carolines to soften them up for our Marines to land. There our carrier planes struck the enemy at the Palau Islands and bombed enemy airfields, sinking three destroyers, seventeen freighters, and five oilers, and damaging another seventeen enemy ships. We shot 160 Japanese planes out of the sky during these air strikes, and destroyed another forty-six on the ground.2

Fighting aboard the Indy was exhausting at times. Many times the Japanese would be firing at us from their island fortifications as we returned fire with our big guns. At the same time, I would be firing my 40 mm guns at their aircraft buzzing overhead to prevent them from hitting us. In my peripheral vision I could see water splashing, planes falling, and smoke rising from some of our ships that had been hit. I remember thinking, This can’t be happening. Am I really here? The noise was deafening and I was terrified, running on pure adrenalin.

In the Western Carolines we manned our guns for seventeen days straight in an effort to destroy the tremendous concrete tunnels and fortifications the Japanese had so effectively built. Tragically, our American forces lost approximately seven thousand men during the months of March and April of 1944 at Yap, Ulithi, Woleai, and Palau. Although loss of life was high, these were strategic victories because they neutralized the enemy’s ability to interfere with the U.S. landings on New Guinea (though some argued we would have been better off to have starved them out than gone in after them).

On June 13, we moved on to the Marianas, where the Indianapolis joined the pre-invasion bombardment group off Saipan. The Japanese were dug in deep on Saipan with their massive gun installations camouflaged and concealed behind trapdoors on concrete bunkers. With the landing attack scheduled for June 15, Admiral Spruance maneuvered the Indianapolis close enough to oversee the attack—so close, in fact, that we experienced many near misses from the Japanese batteries. Fortunately, we were hit only one time by a defective shell that did not explode, causing only minor damage.

Under the cover of ferocious American bombardment, the Second and Third Marine divisions launched their amphibious assault, but they were met with stiff resistance when they came ashore. The well-fortified Japanese bunkers were high above the beaches, capable of quickly opening their massive trapdoors to blast our vulnerable boys below before concealing themselves again. The casualties for our Marines were high. I experienced an almost overwhelming range of emotions that day, everything from fear to fury. Still, not letting our emotions rule us, the crew of the Indy fought on with great discipline, doing all we could to support our vulnerable troops storming the beaches.

The USS Indianapolis under fire by Japanese shore batteries during the invasion of Saipan, June 1944. (U.S. Naval Historical Center)

Desperate to relieve their beleaguered forces to the south in the Marianas, the Japanese launched a large fleet of battleships, carriers, cruisers, and destroyers. According to Tokyo Rose (a generic term for English-speaking Japanese broadcasters that spread propaganda over the airwaves), the Americans were running away from the massive flotilla of the Japanese Navy. To the contrary, Admiral Spruance ordered a fast carrier force to make haste to meet them head on. A second force attacked their air bases at Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima in the Bonin and Volcano Islands. Admiral Spruance was confident of victory knowing that the United States had 104 ships of various kinds and 819 carrier-based planes available in the theater of operation. Estimates for the Japanese, however, indicated that they had suffered serious losses in the Pacific, leaving them with only 55 ships and 430 planes. By then, the U.S. Fleet had twice as many destroyers as the Japanese.

Our fleet met the enemy on June 19 in what was called the Battle of the Philippine Sea, but became known throughout the fleet as the Marianas Turkey Shoot. According to the Navy Department’s Naval History Division, enemy carrier planes had hoped to refuel and rearm at the Guam and Tinian airfields and attack our offshore ships. Instead, they were met by our own carrier planes and the guns of the escorting ships. That day, 402 enemy planes were destroyed while we lost only 17 of our own. In addition to the enemy planes, U.S. carrier planes also managed to sink two enemy carriers, two destroyers, and one tanker, and severely damaged several other ships. The Indianapolis triumphantly shot down a torpedo plane.3

Kamikaze Planes and the Insanity of War

As Japan’s war machine began to fall apart, their desperation gave birth to the concept of suicide planes called kamikazes, meaning “divine wind.” With their planes loaded with explosives and only enough fuel to make it to their designated target, kamikaze pilots would ceremonially step into their cockpits for the last time, with feelings of great pride, and fly off to their death.

Whenever I reflect on these battles, especially the Marianas Turkey Shoot, I find myself shaking my head at the insanity of war. The suicide missions of the Japanese kamikaze pilots serve as a perfect illustration. What a colossal waste of lives and resources—and for what? Most of the Japanese soldiers, especially the officers, considered their emperor a god and worshiped him. They considered it an honor to die for him. Likewise, most Japanese considered themselves Shintoists (belonging to the religion of Shintoism, primarily a mystical religious system of nature and ancestor worship). This belief system was so powerful that it inspired their soldiers to make banzai (fierce and reckless) suicide attacks as an act of religious service. Capture was considered a profound disgrace upon their families, who considered those captured as dead. For this reason Japanese soldiers would rather die than be taken prisoner by the enemy. With such fanaticism, one can only imagine the staggering loss of life if we had been forced to invade Japan with ground forces before they surrendered.

I remember feeling pity for the ones we shot down and rescued. Most were poorly trained young pilots, blinded by a warped sense of patriotism, honor, and, like all suicide warriors, a fanatical religious fervor to serve some phantom god (or gods) that does not exist. I was intrigued as I watched the survivors being lifted out of the sea and placed onto the deck of the Indy. Wounded and scared, I can still see their white pajama-like death uniforms and their young faces overwhelmed with terror and confusion. After dressing their wounds and conducting the customary interrogations, we would transfer them to other ships as prisoners of war.

After the Marianas Turkey Shoot, the Indianapolis returned to Saipan to resume fire support for six days. We then moved on to Tinian to blast shore installations. Meanwhile, Guam had been taken, and the Indianapolis was the first ship to enter Apra Harbor (previously an American base) since the harbor’s capture by the Japanese early in the war.

The Indy’s antiaircraft guns firing at a kamikaze plane (1945).

For the next few weeks we operated in the Marianas area and then proceeded back to the Western Carolines, where further landing assaults were planned. From September 12 through 29, both before and after our landings, we bombarded the Island of Peleliu in the Palau Group. We then went on to operate for ten days around the island of Manus in the Admiralty Islands before returning back to San Francisco to the Mare Island Navy Yard for repairs and maintenance.4

In December 1944 we welcomed our new skipper, Capt. Charles B. McVay III. Unlike Captain Johnson, who was all business in his military demeanor, Captain McVay was more personable and enjoyed interacting with the men. Johnson ran a very tight ship, requiring many drills and calling General Quarters (i.e., being battle ready) early in the morning. McVay, on the other hand, ran a looser ship, not requiring us to be battle ready all the time. This means he didn’t expect us to keep watertight doors closed and dogged (fastened shut) when we were in forward areas. But I never thought of him as being lax in any way.

I served as a Marine orderly for both of these fine captains and had a bit of a firsthand experience with both of them. I still laugh as I recall driving Captain Johnson down to the Navy Yard one sunny day. He was just as much in charge of that jeep as he was the Indy, except on that occasion I was at the controls and the fine captain was in the back seat telling me how to drive.

With Captain McVay now at the helm of the Indy and our overhaul at Mare Island complete, we joined Vice Adm. Marc Mitscher’s carrier task force on February 14, 1945. There we played a vital support role as our forces attacked the installations in the Home Islands of Japan itself. The Indy gave its support to the first air strikes on Tokyo since General Doolittle’s invasion in April 1942, preparing the way for the bloody struggles at the landings on Iwo Jima—one of Japan’s southernmost islands.5

The campaign around the Home Islands stands out in my mind. It was crucial for us to gain tactical surprise, and we did so by traversing the Aleutian Island chain in terrible weather. I remember several occasions where I was at watch on the bridge during high seas. As the ship forged ahead, the bow would descend into the great valleys of water, then plow into the frigid banks of the oncoming waves, causing a sleet-like spray to strike me with stinging force.

Our mission was successful in the Home Islands campaign. Between February 14 and February 17, the Navy lost forty-nine carrier planes while shooting down or destroying 499 enemy planes. Our task force sank one Japanese carrier, nine coastal ships, two destroyer escorts, and a cargo ship. While this was going on, Japan was being systematically devastated every day by our Air Force.6

Iwo Jima

With their homeland under attack and their war machine gradually being diminished, the Japanese fought with a zealous determination. They fiercely defended Iwo Jima, proving to be one of the toughest of all the islands for the United States to secure. An estimated 21,000 Japanese troops inhabited the labyrinth of coral tunnels on the volcanic island. The Indy’s mission was simple: Bombard them! We had the ability to fire over five hundred rounds of 5-inch gun ammunition in under six minutes, sending massive amounts of destructive flak as far as eight miles. The big 8-inch guns could lob 250-pound shells up to eighteen miles. The concussion from the 8-inchers was staggering. In fact, their enormous recoil would actually move the massive Indianapolis sideways in the water. We were also well equipped for close-range warfare with the firepower of our 40 mm and 20 mm deck guns. They were especially effective on kamikaze planes, which were a persistent threat.

I will never forget the day a kamikaze plane flew in low and horizontal, trying to make its way across our bow. As always, our mission was to shoot him before he could get to us. That particular day I was a fuse-box loader on one of the 5-inch guns. I would place a seventy-five-pound shell into a fuse box hitched up to what was called “sky aft radar.” This radar system would then relay the actual coordinates of the incoming enemy plane to the shell itself, instructing it to explode its flak precisely in front of the plane.

As the plane came roaring by from left to right, the 5-inch gun immediately to the left of my gun continued firing in its left-to-right range of motion until its rotation was complete. With its muzzle now approximately sixteen feet from where I stood, pointed as far forward as possible toward the bow of the ship, it fired again. The concussion of the blast was so powerful that it knocked me to the deck while I was still holding the seventy-five-pound shell. The explosion dislodged my cotton earplugs, causing them to fall out and quickly blow away in the Pacific wind. Though I was dazed, God enabled me to get to my feet and load the shell. As it fired, the percussion of the blasts further damaged my unprotected ears, causing temporary deafness and blood to run out of my left ear. While our efforts averted the enemy plane and our lives were spared, I permanently suffered a 50 percent loss of hearing in that ear.

Okinawa

By March 4, 1945, we joined the pre-invasion bombardment of Okinawa, where we fired 8-inch shells onto the Japanese beach defenses. In the seven days of fighting at Okinawa, the crew of the Indy shot down six planes and assisted in splashing two others.

One morning, the ship’s lookouts spotted a single-engine Japanese kamikaze fighter plane diving toward the ship’s bridge. We immediately opened fire with our 20 mm guns, and although we hit the plane and caused it to swerve, the pilot was still able to release his bomb, then crashed his plane on the port side of the after main deck of the Indy. The plane toppled off the ship and fell into the sea, causing little damage to the surface of the ship, but the bomb tore through the deck armor, the mess hall, the berthing compartment below, and the fuel tanks in the lowest chambers before crashing through the bottom of the ship and exploding in the water underneath us. It was a miracle that we suffered only moderate damage.

The official naval report indicated,

The concussion blew two gaping holes in the ship bottom and flooded compartments in the area, killing nine crewmen. Although the Indianapolis settled slightly by the stern and listed to port, there was no progressive flooding; and the plucky cruiser steamed to a salvage ship for emergency repairs. Here, inspection revealed that her propeller shafts were damaged, her fuel tanks ruptured, her water-distilling equipment ruined; nevertheless, the battle-proud cruiser made the long trip across the Pacific to the Mare Island Navy Yard under her own power.7

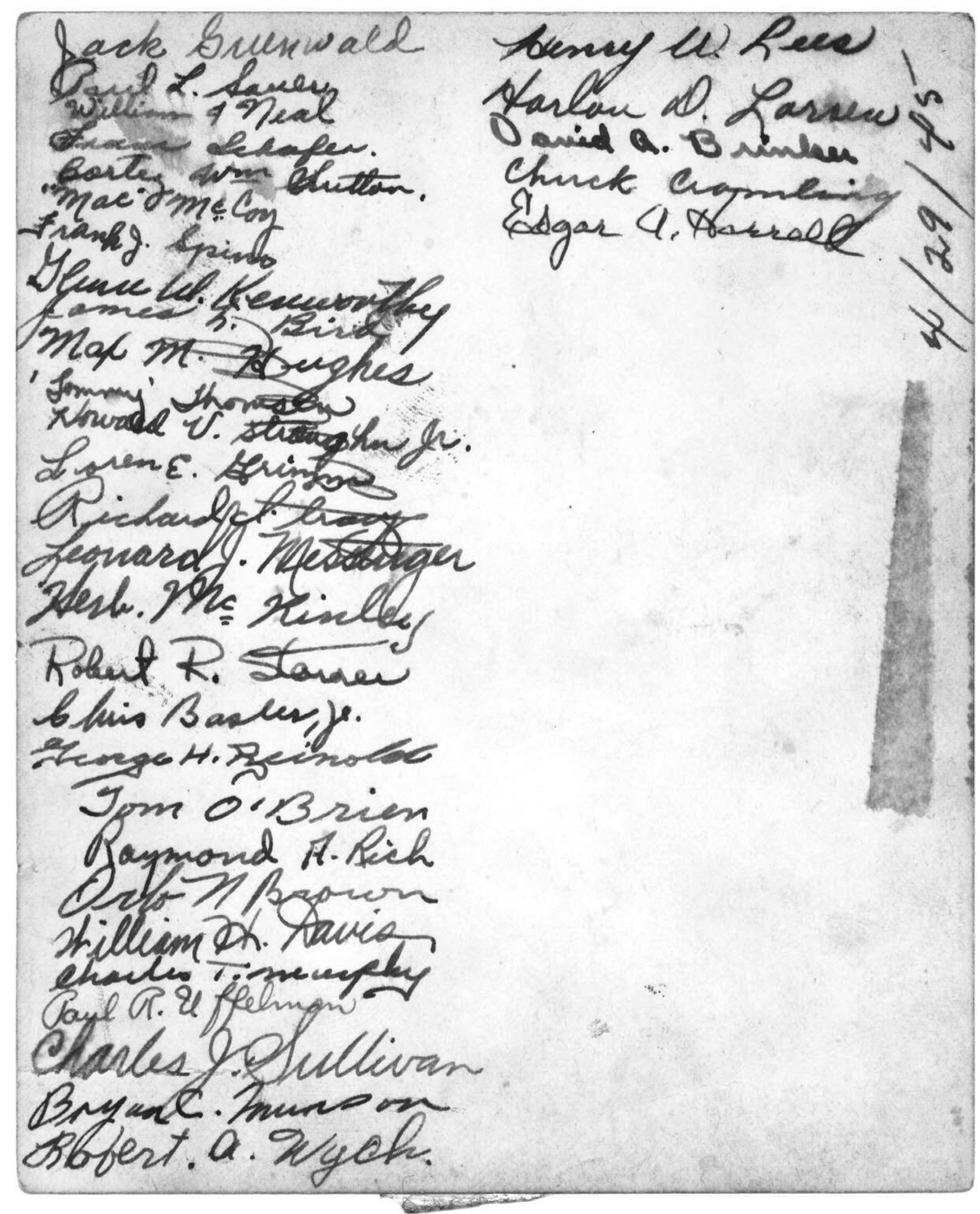

The USS Indianapolis Marine Guard under number 1 turret. I am directly under the middle barrel, middle row (1945).

Signatures of most of my fellow Marines, on back of our photo under number 1 turret.

Top-Secret Cargo

It was a relief to come back to Mare Island and leave the Pacific front. The break from combat was welcomed, but it was short lived. While at Hunters Point in San Francisco, we suddenly received word that all leaves were cancelled. Despite the fact that the Indy was not fully repaired and tested, we were ordered to get underway immediately. Not knowing what was going on, we boarded and quickly followed orders as we loaded last-minute provisions.

There was an obvious tension in the air—a mood of excitement combined with confusion and secrecy. The place was crawling with Marine guards and top military brass. My curiosity was fueled even more when I was ordered to station guards around the mysterious cargo that had been brought aboard. A large crate, measuring about five feet high, five feet wide, and perhaps fifteen feet in length, was hoisted onto the port hangar off the quarterdeck—an area normally used to store, catapult, and retrieve small observation airplanes.

The plywood crate had been latched onto the deck with large straps fastened by countersunk screws. Each countersunk void was filled with a red-wax seal to serve as a tamper indicator. After stationing guards around the mysterious container, I was given orders to do the same for another curious piece of cargo brought aboard that was placed in a compartment on the upper deck, which was reserved strictly for officers.

There I stationed a guard outside one of Admiral Spruance’s unused rooms, since he was not on board at the time. Inside the room was an ominous-looking black metal canister that a couple of sailors had brought on board. The canister was about two feet long and maybe eighteen inches wide, and was padlocked in a steel cage that had been welded securely to the deck floor. A new boarder to the ship by the name of Captain Nolan had the key to the padlock. Adding to the suspense, the crew was warned that whatever happened in the days to come, that canister must not be lost or destroyed. Whatever it contained was obviously of enormous importance. I later discovered that when the black canister was aboard the transport plane, it had its very own parachute, just in case something went wrong.

Captain Nolan and another Army officer who boarded the ship with him, Maj. Robert Furman, remained with the secret cargo. They seemed conspicuously nervous and out of place, and stayed to themselves in the days that followed. Weeks later we discovered that they were not military officers at all, but rather two scientists in disguise from the top-secret weapons labs in Los Alamos, New Mexico. And the cargo? Integral components of the atomic bombs that would be dropped three weeks later on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, code named “Little Boy” and “Fat Man.”

The ominous canister contained uranium-235; it accounted for approximately half the fissionable material possessed by the United States, and it was valued around $300 million. According to one historian, “The contents of the crate were known to only a handful of people: President Truman and Winston Churchill; Robert Oppenheimer and his closest colleagues at the Manhattan Project; and Captain James Nolan and Major Robert Furman, who were now aboard the Indy. In reality, Nolan was a radiologist and Furman an engineer engaged in top-secret weapons intelligence.”8

Full Speed Ahead—a Record Run

On July 16, 1945, at 8:30 a.m., we exited San Francisco Bay and set sail for Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Being one of the fastest ships in the Navy, the Indianapolis made record time, covering 2,405 miles in just over seventy-four hours. Taking just six hours to load up on supplies and fuel, we left Pearl Harbor and immediately sailed unescorted to the island of Tinian, arriving there on July 26. In total, the Indianapolis had set a record of some 5,300 miles covering San Francisco to our B-29 base in Tinian in only ten days.9

Tinian Island, a small island along the Marianas Trench, is approximately twelve miles in length and six miles in width. At just one hundred nautical miles north of Guam, its proximity to Japan made it a strategic B-29 Superfortress airbase. The four runways of the north field were extended to a length of 8,500 feet to accommodate gigantic aircraft burdened with heavy bombs and extra fuel needed to complete nightly twelve-hour round-trip raids on Japan.

Although our bombing raids were having a devastating impact on the enemy, Washington had made plans to invade Japan with two operations involving over two million American soldiers. Under the code name “Olympic,” 800,000 troops were to go ashore on the southern island of Kyushu in November, with a second amphibious assault called “Coronet” to land on the island of Honshu near Tokyo in April 1946.

None of us aboard the Indianapolis had any idea that the mysterious cargo we had just unloaded at Tinian would make all these plans unnecessary. None of us knew that we had just delivered the most devastating weapon in the history of the world. None of us knew that God was using the crew of the Indianapolis to accomplish His purposes in bringing the war to an abrupt and terrifying end. And certainly none of us knew that four days after arriving in Tinian, our beloved Indy Maru and most of her crew would be lost at sea.