7

New Barbarians

We now turn to an artistic visualization of “new barbarians” as they take shape in the photo-performance portfolio “The New Barbarians” (2004–6) by performance artist and writer Guillermo Gómez-Peña and his troupe La Pocha Nostra.1

As discussed previously, Geers’s labyrinth confronts the visitor with the absence of barbarian others, which draws attention to the barbarism in civilization’s structures. The foreign presences conjured by the installation are specters, which modify our perception of the surroundings and ourselves as historical subjects. Sacco’s Esperando a los bárbaros offers metonymical traces of the other by bracketing the body and the face through a close-up on the eyes. By visually staging the invisibility (Geers) or minimal presence (Sacco) of the other, neither of these works brings an end to the waiting by offering representations of barbarians. The absence of barbarians in these two works is counterpoised by their ostensive presence in Gómez-Peña’s project. “The New Barbarians” overwhelms the viewer with an overload of cultural signs in provocative combinations on the bodies of performance personas. If the “waiting” in Geers’s and Sacco’s titles contains the promise of arrival, Gómez-Peña’s “New Barbarians” seem to materialize that promise. The form this materialization takes, however, falls short of the expectations of the civilized imagination.

Born in Mexico City, Guillermo Gómez-Peña moved to the United States in 1987, where he established himself as a prominent performance artist and writer based in San Francisco. In his art projects, performances, and books, he addresses issues of cross-cultural and hybrid identities, migration, globalization, the politics of language, border cultures, border crossings, and the interface between North and South (especially the US-Mexican border) and between mainstream US and Latino culture. His performances, essays, and experimental poetry—in English, Spanish, or “Spanglish” (a combination of English and Spanish)—stage confrontations and misunderstandings between cultures, races, ethnicities, and genders by using various media and technologies.2 In the “ever-evolving manifesto” of his performance troupe La Pocha Nostra, Gómez-Peña describes his troupe as a “transdisciplinary arts organization” that crosses borders “between art and politics, practice and theory, artist and spectator” (2005, 93).

“The New Barbarians” is a large body of work, which, in the artist’s words, intends to “explore the cultural fears of the West after 9/11.”3 It includes the following photo-performance portfolios: “Ethno-Techno,” “Post-Mexico en X-paña,” “The Chi-Canarian Expo,” “The Chica-Iranian Project,” “Tucuman-Chicano,” and “Epcot-El Alamall.”4 These photo-performances also developed into a real-life performance in the format of a fashion show entitled “The New Barbarian Collection,” which premiered in November 2007 at Arnolfini in Bristol. For “The New Barbarian Collection,” Gómez-Peña, his troupe, and a number of European-based artists set up what they called “an X-treme fashion show,” through which they engaged the audience with “fashion-inspired stylized performance personas stemming from problematic media representations of foreigners, immigrants, and social eccentrics, as both enemies of the state and sexy pop-cultural rebels.” This is part of the show’s description on the artist’s Web site: “The show is about politicized human bodies far more than clothing. What is actually being ‘sold’ is a new designer hybrid identity and the human being as a product. The performance also explores the bizarre relationship between the post-9/11 culture of xenophobia and the rampant fetishization of otherness by global pop culture.”5

The photo-performance portfolios composing “The New Barbarians” are expressions of the same rationale. They feature hybrid personas in provocative costumes and props, partly inspired by stereotypical media representations of “new barbarians.” By constructing alternative versions of new barbarians, the project challenges the typecasting of others as barbarians in the West after 9/11. This strange fashion shoot results in photographic portraits with characteristic titles such as Androgynous Guest, Guerilla Supermodel, Islamic Immigrant, Generic Terrorist, Hybrid Gang Banger, Supermodelo zapatista, Turista Neo-Victoriana, and Aristócratas nómadas.

As the only materialization of the figure of the new barbarian I look into, Gómez-Peña’s project occupies an important part in this book. His project engages the theme of barbarism through what I call a “barbarian aesthetic.” I here examine how this aesthetic can contribute to a “barbarian theorizing”—to borrow Walter Mignolo’s term—from the periphery of the West.6

Specifically, this chapter starts with a brief survey of linguistic barbarisms in Gómez-Peña’s work through an analysis of samples from his bilingual writing practices and then explores how visual barbarisms are at work in “The New Barbarians”: elements that do not allow the viewer to synthesize the images into coherent narratives. Gómez-Peña’s personas form a visual “barbarian grammar” based on elements from heterogeneous discursive fields and theoretical idioms. This visual grammar takes up, appropriates, but also questions popular theoretical concepts and frameworks. By overloading the viewer with cultural references, Gómez-Peña’s barbarians tempt us to engage in the game of their theorization, while they simultaneously confound our attempts to theorize them.

By conversing with theory, Gómez-Peña’s barbarians perform their “barbarian theorizing” through and against existing theoretical idioms. This theorizing should not be imagined as a visual demonstration of popular theoretical views. The photo-performances in “The New Barbarians” do not support a theoretical discourse by functioning as post-dictions and making the theory “pre-dictive metaleptically” (Spivak 1992, 776). In other words, they do not just illustrate theoretical propositions but become agents of a visual mode of theorizing. This theorizing, I argue, is based on an attitude of non-seriousness, the implications of which I chart.

These barbarian figures are also compared with other positive conceptualizations of new barbarians, particularly in Walter Benjamin and in Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s Empire. Finally, by unpacking the artistic interventions of Gómez-Peña’s barbarians in relation to Geers’s and Sacco’s installations, I pose the question of these works’ relation to the political, as it ties in with their aesthetic performance.

The Barbarisms of Bilingualism

I am not interested in . . . legitimizing the global by reversing it into the local. I am interested in tracking the exorbitant as it institutes its culture.

—Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Acting Bits/Identity Talk”

Gayatri Spivak argues that what we call “culture” stands for “an unacknowledged system of representations that allows you a self-representation that you believe is true” (1992, 785). Following this logic, Spivak continues, US culture is “the dream of interculturalism: benevolent, hierarchized, malevolent, in principle homogenizing, but culturally heterogeneous” (785). As this hegemonic system is taking over the globe, however, people tend to forget that the word American accompanies every manifestation of US interculturalism—as in “African-American,” “Mexican-American,” “Muslim-American” (885). This suggests that in US inter-culturalism there is still an overarching cultural authority, a hegemonic center, toward which all cultural forces are drawn. This kind of hierarchized interculturalism accommodates minor identities and (sub)cultures as long as they conform to the homogenizing normative principles of US culture and acknowledge the English language as the global language of communication—a lingua franca.

In his writings and performances, Gómez-Peña expresses his fear of English becoming the only language in an authoritarian state. The following quotation from one of his performances is characteristic:

I dreamt the US had become a totalitarian state controlled by satellites and computers. I dreamt that in this strange society poets and artists have no public voice whatsoever. Thank God it was just a dream. In English. English only. Just a dream. Not a memory. Repeat with me: Vivir en estado del sitio is a translatable statement; to live in a state of siege es suseptibile de traducción. In Mexican in San Diego, in Puerto Rican in New York City, in Moroccan in Paris, in Pakistani in London. Definitely, a translatable statement. (Gómez-Peña, quoted in Spivak 1992, 791).

Against the totalitarian impact of the English language, Gómez-Peña describes and performs a counter-suggestion: speaking simultaneously in multiple languages, mixing linguistic codes, and creating new idioms, in which the English language loses its hegemonic force, as it is made to coexist and interact with different languages. “Vivir en estado del sitio is a translatable statement; to live in a state of siege es suseptibile de traducción.” The repetition of the first phrase in reverse translation pleads for the equal standing of the languages participating in this sentence.

However, Gómez-Peña here does not advocate an absolute translatability according to which every utterance could be transferred into another language without any change or loss. If that were the case, there would be no point in resisting the idea of a lingua franca. Gómez-Peña’s writings and artistic practices probe issues of (un)translatability. He often speaks or writes in Spanglish and inserts foreign words and phrases (primarily Spanish) into his English texts. This practice is in accordance with Chicano language, which consists of a version of American English with elements of a pseudo-Mexican slang.7 The following piece is part of a performance text from 2004, “To Those Who Are As Afraid of Us As We Are of Them”:

I speak therefore I continue to be a part of “us”

To the shareholders of monoculture

I say, we say:

We, bilingual, polylingual, cunilingual,

Nosotros, los otros del mas allá

del otro lado de la linea y el Puente

We, rapeando border mistery; a broader history

We, mistranslated señorrita,

eternally mispronounced

We, lost and found in the translation

lost and found between the layers of this text

We speak therefore you cease to be

even if only for a moment

I am, US, you sir, no ser

Nosotros seremos

Nosotros, we stand not united

We, matriots and patriots

We, Americans with foreign accents

We, Americans in the largest sense of the term

(from the many other Americas)

We, in cahoots with the original Americans

who speak hundreds of beautiful languages

incomprehensible to you

We, in cahoots with dozens of millions of displaced

Latinos, Arabs, Blacks and Asians

who live so pinche far away from their land

and their language

We feel utter contempt for your myopia

and when we talk back, you lose your grounds.

(Gómez-Peña 2005, 231–32)

The poetic voice in this text is a collective “we,” explicitly addressing a “you.” The “we” and the “you” seem to delineate a distinction between a heterogeneous, multicultural, polylingual group vis-à-vis the monolingual “shareholders of monoculture.” The latter group most likely refers to mainstream US culture and its use of English as a lingua franca.

Although the multilingual “we” is clearly opposed to the “you,” it does not stand outside it. The we includes “Americans” but “with foreign accents” and “in the largest sense of the term / (from the many other Americas).” It would perhaps be more accurate to say that the we is situated at the margins of the you. This plural, marginal we poses a threat to the monoculture of the you. This threat stems from the incomprehensibility of the we to the you: the “hundreds of beautiful languages” we speak are “incomprehensible to you.” If power and control over the other are based on knowledge, then the barbarian languages of the we confuse the you and deprive it of its sense of control over its marginal others. As a result, the we threatens the very grounds of the existence of the you: “We speak therefore you cease to be,” “and when we talk back, you lose your grounds.”

What I find most fascinating about this performance piece is not its propositional content as such—the idea that the margins can challenge the center through their difference and linguistic pluralism—but the way this idea is performed in language. This central idea is enacted through a series of linguistic barbarisms, through which the challenge of the polylingual margins to the monolingual center materializes in language.

The piece is bilingual, with several Spanish verses, phrases, or words interrupting the flow of the English text. There is no strict division between the English and the Spanish: the two languages interfere not only within the same verse but sometimes even within the same word. This mutual interference takes different forms, including neologisms, unorthodox word combinations, errors, misspellings, surprising alliterations, puns, and wordplays. New words are devised based on common English words. For instance, the neologism “matriots” is placed near the word “patriots” in a juxtaposition that denaturalizes the latter by drawing attention to its etymology and, through it, to its patriarchal origins.8 Similarly, the word “cunilingual” is modeled after “bilingual” and “polylingual.”

Apart from neologisms, there are also Spanglish phrases and words, such as “rapeando,” in which the English verb “rap” is adjusted to the Spanish conjugation for present continuous. In the same verse, the juxtaposition of “border mistery” and “broader history,” and the striking alliteration and rhyming it produces, acoustically creates a broadening of borders from lines into spaces (border–broader). On these border spaces, “history” is not a fixed account but still a “mistery” and can thus be rewritten to include the histories of border cultures and of “Americans in the largest sense of the term.” “Mistery” is misspelled, perhaps under the influence of the “i” of “history.” Another linguistic error follows in the next verse: “We, mistranslated señorrita, / eternally mispronounced.” Here, the poetic voice slightly misleads the reader: while “mistranslated” and “mispronounced” urge the reader to look for mistakes in translation or pronunciation, the actual error lies in the spelling of the word “señorrita,” wrongly spelled with a double r.

In the verse “I am, US, you sir, no ser,” alliterations and the mixture of languages generate different semantic possibilities. Starting with the English “I am,” the verse ends with the Spanish “no ser” (not to be). The negation of existence implied in “no ser” puts the English “I am” into question and implicitly refers to the verse “We speak therefore you cease to be.” The Spanish “no ser” functions as a barbarism that haunts the identity of the mainstream culture, confidently affirmed by the phrase “I am” with “US” right next to it. In the second part of the verse, “you sir, no ser” sounds very similar to the phrase “yes sir, no sir,” which holds connotations of servile obedience and subordination.9 These connotations are at odds with the overall function of this verse, which triggers insubordination to the dominant language through linguistic barbarisms and thereby questions the authority of the “US” and the English “I am.” The submissiveness of the “yes sir, no sir,” acoustically hidden within the more insurgent “you sir, no ser,” reminds us, however, that no act of contestation is permanent. A barbarism with a destabilizing function within a certain context may also turn into a confirmation of, or an act of subordination to, the dominant culture.

This observation also suggests that marginal groups and border cultures—the poem’s “we”—do not by definition contest the dominant simply by occupying the margins. In fact, marginal groups often try to impose their own “universal” truths and hegemonic positions or imitate the mechanisms and power structures of the mainstream culture.10 Thus, the margins should also be under critical scrutiny. This is also suggested in one of Gómez-Peña’s “Activist Commandments of the New Millennium”: “Confront the oppressive and narrow-minded tendencies in your own ethnic- or gender-based communities with valor and generosity. The ‘enemy’ is everywhere, even inside ourselves” (2000, 93).

Through its barbarisms, Gómez-Peña’s performance text shows how the heterogeneous, polylingual, mistranslated, misspelled, mispronounced, misunderstood “we” threatens the premises of the “shareholders of mono-culture.” The polylingualism of those other Americans is perceived as a threat precisely due to the mainstream culture’s insistence on unity. In the face of the patriotic motto “united we stand, divided we fall,” commonly used in US political speeches and popular culture, Gómez-Peña writes in the same performance text: “Nosotros, we stand not united.” The gist of the former motto is that as long as people stay united, they cannot be easily destroyed. Here, this message is revised. When unity becomes a homogenizing principle of consensus that distrusts and marginalizes foreign elements, this artificial unity is not as strong as one may think. Such a unity suppresses the tensions, conflicts, and agonistic elements that arise at the borders between “languages,” where different idioms, ideas, practices, and cultures rub against and into each other. These tensions come alive in Gómez-Peña’s performance text. The tensions between languages need not be a threat to their respective unity but can form political sites of contestation. In this way, Gómez-Peña turns the non-unity of a multilingual, heterogeneous “we” into a source of empowerment.

The barbarisms Gómez-Peña inserts in this piece, as well as in other of his writings, challenge the reader to operate in two linguistic systems simultaneously. As one system is measured against the other, their limitations, problematic aspects, and power relations are also brought to the foreground. The foreign words and phrases that interrupt the flow of the English demonstrate the impossibility of an absolute transference of meaning through translation. It is impossible to replace them by English words and still retain the same meaning and effect.

“Vivir en estado del sitio is a translatable statement; to live in a state of siege es suseptibile de traducción.” Rereading this statement by the artist, I cannot “translate” it as a naïve endorsement of translatability but as staging the possibility of transforming the dominant language when we place it next to another language. This transformation is possible even when one lives “en estado del sitio”—under the suffocating influence of an Anglo-dominated culture. “To live in a state of siege” is a translatable statement, and the linguistic reversal that takes place in its translation suggests that the content of the statement is also reversible. A way of reversing the tyranny of monolingualism is by infusing the dominant language with barbarisms. This is a common practice in Gómez-Peña’s performance texts, but what happens to this practice when we move from the textual to the visual realm?

From Visual Mimicry to a Babelian Performance

Gómez-Peña’s practice of using two (or more) languages simultaneously and inserting barbarisms into dominant idioms finds a parallel in his visual strategies. In “The New Barbarians” different visual codes interact and clash with each other. The barbarian personas borrow elements from diverse sources: media representations of “evil others,” bits and pieces from American popular culture (fashion shows, movies, TV, comics, rock and roll, hip-hop), border and Chicano culture, Western high art, the history of the visual and performing arts, religious imagery, journalism, anthropology, and pornography. Oversaturated signs from these sources form unorthodox combinations, constructing an array of eccentric barbarians.

Typologies of barbarians in contemporary Western media and politics belong to a strictly coded representational regime. Although the tag of the barbarian is conferred on diverse “others,” the media-construed personas of these others bear fixed features, which ensure their recognizability by the public. By distorting a repository of stereotypes, Gómez-Peña’s barbarian personas perform and parody the West’s fear of others, especially since 9/11.

These personas are located at the US periphery and at the interface between mainstream Western and non-Western cultures (mainly Latino and Middle Eastern). With this in mind, one can argue that Gómez-Peña’s “New Barbarians” employs the strategy Homi Bhabha calls “colonial mimicry,” a strategy of appropriating colonial discourse in a way that produces “its slippage, its excess, its difference,” resulting in the disavowal of its authority (1994, 122–23). Colonial mimicry reads Western narratives in unconventional ways or employs them for purposes not foreseen by the dominant culture (Bhabha, presented in Moore-Gilbert 1997, 131–32).

Certain photographic performances in “The New Barbarians” enact a visual mimicry of Western classical themes. For instance, Piedad postcolonial from the portfolio “Post-Mexico en X-paña” is a postcolonial appropriation of a classic subject in Christian art, the pietà, which depicts the Virgin Mary in grief, cradling the dead body of Christ.11 In Gómez-Peña’s Piedad the role of the Virgin Mary is performed by a man, dressed as a Native American from the waist up, and in drag from the waist down, wearing a long black skirt.12 The man is holding an ax in his left hand, and with his right arm he is supporting a naked dead body. Instead of showing grief or meditative sorrow—as the Virgin Mary does in the Western tradition—this Native American is looking away from the dead body and has an austere expression. The exposed breasts and genitals of the dead body supported by his arm suggest that the Christ figure is female (unlike the body of Christ, covered with a loincloth in the classical pietà). Nevertheless, the body structure looks somewhat masculine. The head is shaved, which confuses the viewer’s attempt to assign a sexual identity to this persona. The facial characteristics are partly indistinct, as the largest part of the face is painted red, as if wearing a mask. This queer body has one stereotypically recognizable racial feature: the eyes suggest that the figure playing the dead Christ is of Asian descent.

Hardly any of the elements in the classic pietà theme remain intact in this staging, apart, perhaps, from the position of the dead body. The participating figures—a Native American (played by Gómez-Peña) and (possibly) an Asian—are foreign to classical Western culture. The gender roles of the pietà are also confounded, with the Virgin Mary as male and the body of Christ as female and queer. The stern expression of the Native American figure and the ax he holds suggest that either he has killed the person he is holding or he is determined to avenge her death. The violent connotations of the ax and the man’s defiant expression turn the Christian narrative of the grieving mother upside down. The association of Christianity with violence unsettles this narrative. The image strongly evokes the role of Christian Europe in the annihilation of the Native American population. If the dead body is a visual synecdoche for this annihilation, then we can read the man’s expression as grief and anger, and his ax as a pledge for revenge.

The suggestion that Christianity has committed worse crimes against Europe’s others than the crime staged in the pietà robs the Christian narrative of its sanctity. The new Piedad casts a critical eye upon its Western “original,” but it also contains visual ambiguities—barbarisms—that prevent us from categorizing it as a straightforward anticolonial narrative. The Asian features of the dead body, for example, could be a hitch in such a narrative. Other confusing elements are the gender of the Christ figure, as well as the hybrid costume of the man, combining caricatural Native American and drag elements. These elements turn the image into a complex intersection of cultural, gender, queer, (anti- and post-)colonial, historical, religious, and racial discourses, which deter us from situating it within a singular framework.

“The New Barbarians” project includes two more translations of the same Western theme: La piedad intercontinental and La piedad intercontinental (invertida), both from the portfolio “Chi-Canarian Expo.”13 Other photo-performances that appropriate Western religious themes are La dolorosa (from the portfolio “Chi-Canarian Expo”) and Sagrada familia (from the portfolio “Post-Mexico en X-paña”). Sagrada familia stages a comparable “blasphemous” recasting of the religious theme of Joseph, Mary, and baby Jesus, staged by three very unlikely figures: a weighty Arab man holding a gun (Joseph), a Muslim woman covered with a black burka but with her legs exposed in a seductive pose (Mary), and a third figure wearing an oxygen mask and underpants with the Superman logo—a parody of the “almighty” Jesus.

FIGURE 7.1 Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Piedad postcolonial, 2005. From the portfolio “Post-Mexico en X-paña.” Photograph by Javier Caballero (original photo in color, reproduced here in black and white). Courtesy BRH-LEON editions.

As performances of colonial mimicry, these images turn Western iconography and religious narratives against themselves. In doing so, they uncover the contradictions that inhere in Western culture itself, such as that of a religion proclaiming love and mercy and instigating brutal wars and barbarism.14 The association of Christianity with barbarism was also brought forth by Geers’s installation. This association suggests that contemporary Western condemnations of Islam as a barbaric religion turn a blind eye to the barbarism committed in the name of Christianity in history.

The unlikely personas featuring in these restagings of Western high art also allude to the non-Western origins of Western art and its influences from other cultures. By exposing these interconnections with other cultures, as well as the internal contradictions in Western discourses, Gómez-Peña’s barbarians manage to pluralize the West itself. The West is barbarized and emerges as a collective heritage, constituted by various non-European influences.

By critically recasting Western narratives, Gómez-Peña’s barbarians do not impose a new authoritative narrative in the place of the one they rewrite. Although they project alternative histories from the margins, the bits and pieces of these histories do not add up to a coherent account issued from a uniform perspective. They draw from diverse ethnic, racial, cultural, and gender discourses and unravel their critique by mobilizing various theoretical perspectives—queer, anticolonial, postcolonial, posthuman—without pledging dogmatic allegiance to any of them. The photo-performances in “The New Barbarians” do not propose a unified anti-Western narrative but a syncretic, barbarian visual idiom, which contradicts the very possibility of a homogeneous cultural narrative. Their visual grammar does not fit within a singular representational framework or theoretical discourse.

The confrontations that “The New Barbarians” stages between diverse discourses expose the inconsistencies and blind spots in these discourses. Things normalized within a certain cultural framework—the burka in Muslim communities, an ax or saw in the hands of a carpenter, a cross in the hands of a priest, sexy lingerie on female bodies on Western billboards and in commercials, machine guns in the military, red feathers on Native Americans in American westerns—are transformed into ex-centricities. They lose their reference to the center that issues their normalization because they are integrated in foreign visual idioms: a burka covering a woman with fully exposed legs (Islamic Immigrant), a cross next to a gun in the hands of a “gang banger” (Hybrid Gang Banger), or a bandit figure from a western (El Spaghetti Greaser Bandit), women’s lingerie on a male body (Androgynous Guest) or on a military cyborg (Ciborg miliciana), a machine gun held by a neo-Victorian/Native American female tourist (Turista Neo-Victoriana), and red feathers on the head of an Amazonian Indian in drag, occasionally posing as the Virgin Mary (El indio amazonico, La piedad postcolonial).

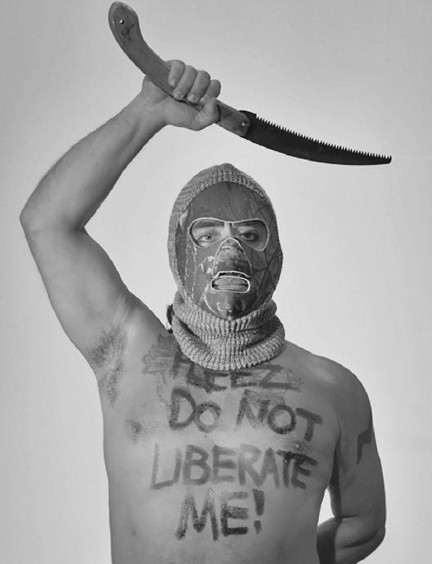

FIGURE 7.2 Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Generic Terrorist. Photograph from “The Chica-Iranian Project” portfolio (original photo in color, reproduced here in black and white). Photograph by James McCaffrey. Source: Gómez-Peña et al. (2006, figure 4, p. 20). Reproduced by permission of Sage Publications.

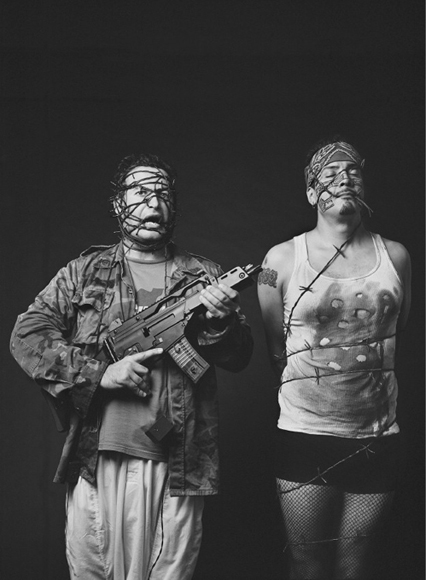

FIGURE 7.3 Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Hybrid Gang Banger. From “The Chica-Iranian Project” portfolio (original photo in color, reproduced here in black and white). Photograph by James McCaffry. Source: Gómez-Peña et al. (2006, figure 7, p. 23). Reproduced by permission of Sage Publications.

Thus, these images often exceed the practice of colonial mimicry and engage in what we could call—borrowing Jacques Derrida’s term—a “Babelian performance”: a performance that demands and simultaneously forbids translation by projecting the unfeasible univocity and transparency of signs.15 This visual Babelian performance invites translation into a familiar narrative and simultaneously makes this translation impossible. These personas speak a barbarian language, which plunges the center’s dream of a lingua franca into a sea of errors, cacophonies, and incongruities.

FIGURE 7.4 Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Islamic Immigrant. From the “Tucuman-Chicano” portfolio (original photo in color, reproduced here in black and white). Photograph by Ramon Treves. Source: Gómez-Peña et al. (2006, figure 8, p. 24). Reproduced by permission of Sage Publications.

The aspirations of the United States to establish English as a common language and to “translate” the difference of minorities in the dominant discourse could be visualized as the dream of a contemporary Tower of Babel. The performance of Gómez-Peña’s barbarians impedes the construction of this tower by showing what happens when the translating impulse goes mad. These barbarians reap stereotypical images out of their usual context and make cultural signs coexist with signs from different visual orders and typologies of others. As a result, the letters that make up the Western visual alphabet are rearranged in a barbarian visual grammar, although the images may still remind us of things we have seen on TV. Gómez-Peña’s troupe sees itself as “a virtual maquiladora (assembly plant) that produces brand-new metaphors, symbols, images, and words to explain the complexities of our times” (Gómez-Peña 2005, 78). Their language contains barbarisms—elements used in improper ways, which contaminate the imagery we have internalized as citizens of the West. The name of Gómez-Peña’s troupe, La Pocha Nostra, is a Spanglish neologism and thus itself a barbarism, while it also signifies barbarism (in the sense of foreignism or contamination): one of the possible translations of La Pocha Nostra, as we read in the troupe’s manifesto, is “our impurities”; another is “the cartel of cultural bastards” (78).

Recasting the Stereotype

“The New Barbarians” may be interpreted as expressions of the dream of a transcultural world, wherein people exchange identities and construct themselves as they please. Nevertheless, I argue that their vision of identity is of a different kind. Melancholic, apathetic, perplexed, or distant, most of these personas do not look like happy citizens of a hybridized world.

What kind of vision of identity does “The New Barbarians” act out? And what do these barbarians do with stereotypical images of barbarian others? “The Chica-Iranian Project” is a good theoretical object for probing these questions. In “The Chica-Iranian Project,” Gómez-Peña and a group of mainly Chicano and Iranian artists “exchange” and alter each other’s identities. They create twelve barbarian personas in “ethnic drag,” which incorporate Hollywood and media typecasting and stereotypes of Middle Eastern terrorists, Latino “gang bangers,” and other “evil others” from these two cultural spaces. As we read on Gómez-Peña’s Web site, the resulting photo-performances are meant to visualize the dangers of ethnic profiling in the post-9/11 era. The subtitle of the project—“Orientalism Gone Wrong in Aztlan”—hints at the confusions and “mistranslations” that take place in this Oriental/Latin American mix.16

The presentation of this portfolio on Gómez-Peña’s Web site takes place through an interactive game with the viewer, entitled “Test Your Ethnic Profiling Skills.” The viewer is asked to match the names of the participating artists with the performance personas they have constructed. The underlying question of the game is, “Can the US differentiate between Mexicans and Iranians? Between ‘Latinos’ and ‘Middle Easterners’?” The game sets a trap: The viewer will most probably fail this classification exercise. Guessing the artists’ “real” ethnic affiliations (Chicano, Iranian, and, in the case of one artist, Hapa/half-Japanese) behind their ethnic personas is not easy. In most cases the artists’ personas deviate from their own ethnic affiliation. The Typical Arab Chola is played by a Chicana artist, El Spaghetti Greaser Bandit by an Iranian artist, Palestinian Vato Loco and Generic Terrorist by Gómez-Peña, who identifies himself as Post-Mexican, La Kurdish llorona by a Hapa/half-Japanese artist, and so on.

The probable failure of the viewer to win this guessing game brings out the misconceptions involved in ethnic profiling. As Gómez-Peña remarks elsewhere, ethnic profiling has become an accepted practice after 9/11, and the category “Arab-looking” includes most Latinos and brown people as well. As a result, all these ethnic others have “become an ongoing source of anxiety and mistrust for true ‘patriotic’ Americans” (2005, 274). Staged as an interactive game, “The Chica-Iranian Project” makes the viewer/player complicitous with practices of ethnic profiling and the resulting “misunderstandings” that turn people into victims of hate speech, violence, and discrimination.

Although cultures and ethnicities mix more and more as a result of globalization, people still cling to simplistic representations in order to make sense of the chaotic realities around them. Stereotypes offer a secure point of identification for social groups, assisting them in defining themselves against their reductive representations of others. Although the stereotype itself, as Ruth Amossy and Therese Heidingsfeld argue, is “necessarily reductive,” it does not always have to be involved in “reductive enterprises” (1984, 700). They suggest a functional approach to stereotypes, focusing on their shifting operations in the interaction between text and reader (or image and viewer) (700).17 In Declining the Stereotype, Mireille Rosello suggests that it could be more useful to ask, “What can I do with a stereotype?” instead of trying to eradicate or oppose it (1998, 13). “The Chica-Iranian Project” probes precisely this question. It acknowledges the power and ineradicability of stereotypes, and instead of trying to eliminate them, it plunges into our preconceptions in order to perform them otherwise.

The project does not replace stereotypes of Middle Eastern and Latino others with positive and more true-to-life representations of these groups. Instead, it interrogates the economy of the stereotype itself. A stereotype, according to Amossy and Heidingsfeld, is a hyperbolic figure of a cultural model, which exacerbates the general rule and presents itself “in the margin of excess where forms become fixed and hardened” (1984, 690). However, there is ambivalence at the heart of a stereotype: it oscillates between something already known and taken for granted, and something that must be constantly and anxiously reconfirmed through repetition (Bhabha 1994, 95). This suggests that the “known” in the stereotype is not as securely established as the rhetorical force of the stereotype might suggest (Moore-Gilbert 1997, 117). Stereotypes must be repeated in order to maintain their force. This repetition also makes shifts in their pervasive functions possible.

The project makes use of this ambivalence by reproducing stereotypical images of Latinos and Middle Easterners with a twist. The barbarisms inserted in the images unsettle the homogeneity of stereotypical patterns. Such barbarisms are the message written on the naked chest of the Generic Terrorist that reads “Pleez do not liberate me,” the American flags that form the pattern of the burka in Afghani Immigrant in Texas, or the cloth with an Arab script that the Cigar Shop Indian Chief is holding.

Whenever a stereotype is reproduced, Amossy and Heidingsfeld argue, elements that happen to disturb the pattern of the stereotype are “relegated to the level of ‘remnants’” (1984, 693). The reader or viewer is trained to disregard those remnants by viewing them as details that individualize a stereotypical image or add to its reality-effect (693). This, however, happens on the condition that these remnants “be neither completely heterogeneous nor visibly contradictory” (695). “The Chica-Iranian Project” does not meet this condition. The “leftovers”—the elements not recognized as part of the stereotype—are very hard to neutralize or ignore because they are in stark contrast to the narratives each stereotypical image evokes. They stand out as unfitting intrusions, sabotaging the reassuring déjà-vu effect that stereotypes produce (695).

The Generic Terrorist, for instance, reproduces the figure of the Arab suicide bomber. But it is the message “Pleez do not liberate me” on the chest of this figure that becomes the crux of the image. Instead of being neutralized by the image’s stereotypical elements, it attracts the viewer’s attention because it carries a different narrative. Where we would perhaps expect a message praising the glory of Allah or proclaiming “death to infidels,” this message ironizes the Western conviction that nonliberal societies are waiting for the West to save, liberate, and enlighten them by imposing democracy and liberal values on them. Thus, this deviant element prevents the stereotype of the Middle Eastern terrorist from being unproblematically recuperated.

The barbarians in “The Chica-Iranian Project” do not make claims to a true, essential identity by trying to set a “wrong” representation “right.” The contamination of ethnic stereotypes in this project performs the impossibility of articulating stable ethnic or cultural identities. As Rosello argues, stereotypes imply a theory of identity and can thus be employed “to exclude, to police borders, to grant or deny rights to individuals” (1998, 15). If stereotypes help draw clear-cut ethnic distinctions, then the barbarian ethnic others in “The Chica-Iranian Project” try to blur these lines. They infuse stereotypes with barbarisms—elements that confuse, as Spivak puts it, “the possibility of an absolute translation of a politics of identity into cultural performance” (1992, 782). As a result, they blur the identities of minority voices “without creating a monolithic solidarity” (782).

In his article “The New World (B)order” Gómez-Peña writes about new identities in the contemporary world:18 “This new society is characterized by mass migrations and bizarre interracial relations. As a result new hybrid and transitional identities are emerging. . . . The bankrupt notion of the melting pot has been replaced by a model that is more germane to the times, that of the menudo chowder. According to this model, most of the ingredients do melt, but some stubborn chunks are condemned merely to float” (1992/1993, 74). In these reflections, Gómez-Peña sees models of cultural assimilation—the concept of the “melting pot”—as a failed and outmoded experiment. In proposing the “menudo chowder” model, he focuses on its stubborn chunks: the elements that cannot be translated in the dominant idiom.19 In his discussion of Gómez-Peña’s “menudo chowder” model, Bhabha sees these “chunks” as the basis of cultural identifications, which take place through performative operations. According to Bhabha, these chunks are spaces “continually, contingently, ‘opening out,’ remaking the boundaries, exposing the limits of any claim to a singular or autonomous sign of difference—be it class, gender or race” (1994, 219). In the performance of “The New Barbarians,” the chunks that refuse to go away can be identified as visual barbarisms: discordant elements that prevent the viewers from synthesizing the elements of the image into a coherent narrative.

The visual incommensurabilities in Gómez-Peña’s personas give expression to the internal contradictions in Western visual narratives. The persona entitled Islamic Immigrant is a case in point. The image features a woman sitting on a chair with her legs crossed in a seductive pose. The woman is holding a rifle and wearing a black burka that cloaks her face and upper part of her body, revealing only the eye area. Her legs, however, are exposed and attract attention due to the sexy pantyhose and high-heeled shoes. The background is covered by wallpaper with a military camouflage pattern. In this image, the female Islamic immigrant is portrayed as a hooker, a religious fundamentalist, and a terrorist: an outrageous condensation of stereotypes in one image. Her portrait contains all the contradictory ingredients of the stereotypes of Oriental peoples, especially Muslims: she embodies a rampant sexuality; she follows strict religious prescriptions that restrain this sexuality; she looks enigmatic, erotic, and treacherous; and she poses a violent (possibly terrorist) threat. This threat is suggested not only by the rifle and the military-patterned wallpaper but also by the juxtaposition of the gun and the burka—a connection reminiscent of the practice of Muslim women during anticolonial struggles to carry guns under their burkas. The interlacing of all these stereotypes highlights the inconsistencies and absurdities in popular representations of Islamic women immigrants and undercuts the credibility of these representations. Since the image does not add up, the reality-effect of its stereotypical elements is put under suspicion.

The personas in “The New Barbarians” become visual metaphors of an irretrievable “reality.” The designation “barbarians” here refers to a set of highly stylized figures. I argue that the theatricality and hyperbolic performance of these overtly fabricated figures underscore the catachrestic nature of the name “barbarian”: the fact that this name does not correspond to a real presence but is a “concept-metaphor without an adequate referent” (Spivak 1993, 60).20 Defined as a name applied “to a thing which it does not properly denote,” a catachresis is always an approximation, a misfit, an improperly used word “for which there is no adequate literal referent.”21 The concept of catachresis is crucial in Spivak’s thought as a reminder of the perils of transforming a name to an actual referent (156).22 Against this essentialist tendency, catachresis points to the breach between a name and its referent, while it recognizes the inescapability of using this name—though always with the awareness that its use is improper.23

Gómez-Peña’s barbarian figures embody the impossibility of literalizing the metaphor of the “barbarian.” The cultural references and discursive fields that permeate them make them anything but “literal.” Just as these figures deliberately fail to represent “real barbarians,” any attempt to attach the term “barbarian” to real human beings can never fully succeed. In this way, these personas contribute to the perpetuation of the “waiting” for barbarians, seen as the desire for an inaccessible presence. They point out that we can never match the name “barbarian” to a literal referent because that referent does not exist outside discourse. The name “barbarian” is always a misuse; it may be applied to bodies of others, but it cannot grasp them through this designation. Therefore, Gómez-Peña’s personas point to the dangers of using this appellation. Its use is accompanied by the violence of a misuse, suggested here by the improper and mismatched combinations of signs on the bodies of “The New Barbarians.”

A Non-serious Theorizing

In this time and place,

what does it mean to be “transgressive”?

What does “radical behavior” mean after Howard Stern,

Jerry Springer, Bin Laden, Ashcroft, Cheney,

six-year-old serial killers in the heartland of America,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

what else is there to “transgress”?

Who can artists shock, challenge, enlighten?

—Gómez-Peña, from “Post-Script: Millennial Doubts”

The hyperbolic performance of Gómez-Peña’s barbarians creates a distance from the viewer. This distance is enhanced by the way these personas lay bare the act of acting: everything, from the general setup of the images to the posture of the barbarians, indicates that we are dealing with a staged, highly stylized performance, with no pretensions to subtlety or realistic representation. Their performance can be articulated in terms of the Brechtian approach to acting: the actor maintains a certain distance from the role, which may be perceived as “coldness and haughtiness” (Jameson 1998, 75). This attitude also marks the acting of the barbarian personas. The performance artists create a distance not only from the roles they embody but also from the viewer. In a Brechtian vein, they provoke the viewer without inducing empathy and identification, inviting viewers to think and reflect rather than relate to them.

The ironic distance these personas take from the viewer allows us to watch images with disturbing, confrontational, and violent elements. These include no less than dead animals (e.g., El chamán travesti, Supermodelo zapatista); dead people (e.g., La piedad postcolonial, La piedad intercontinental); knives, axes, pistols, and machine guns (e.g., Sin título, Alianzas aleatorias, Ciborg miliciana, Unapologetic Evil Others); naked bodies in bondage with their heads and faces covered or with their limbs attached to instruments of torture (e.g., Desencuentro total, Re-enactment), people wrapped up in barbed wire (Abu Ghraib Reenactment), and so on. The emotional impact of the violence staged by Gómez-Peña’s barbarians is in my view dampened by means of their excessive, staged, non-serious character.24 The viewer is unable to identify with them because they are far removed from our subjectivity. In Brecht’s theory, this distancing is a necessary ingredient of the Verfremdungseffekt (defamiliarization or estrangement-effect).25 The action must be alienating in order to shatter the illusion that what we see is real. By obstructing emotions based on identification, Gómez-Peña’s barbarians invite reactions that do not rest on sentimentalism or sympathy but on the shock of nonidentification. This shock is part of the critical thinking these barbarians trigger—a thinking that manages to be politically engaging through its distance.

One political ramification of the theatricality of these barbarians is the antiessentializing of the barbarian. The “barbarian” becomes an array of staged roles rather than an inherent quality of certain subjects. In these performances, it is as if civilization dresses up its others in barbarian costumes and has them perform their role as “evil others.” The projection of the barbarian as a series of staged roles has further implications. As Jameson argues, the Brechtian performance not only foregrounds the act of acting but wants to show to the audience “that we are all actors and that acting is an inescapable dimension of social and everyday life” (1998, 25). Gómez-Peña’s barbarians highlight acting as an indispensable aspect of social life. But how does this Brechtian insight, in the way the barbarian personas perform it, function in a contemporary context?

On one level, the theatricality of the barbarians brings out the theatricality in contemporary US culture—a culture wherein, as has so often been claimed, spectacle is indistinguishable from reality. American performance culture permeates everyday life but also the realms of politics, war, and torture. Describing his reaction to a photograph of a prisoner tortured by the US army, Slavoj Žižek remarks: “When I saw the well-known photo of a naked prisoner with a black hood covering his head, electric cables attached to his limbs, standing on a chair in a ridiculous theatrical pose, my first reaction was that this was a shot from the latest performance-art show in lower Manhattan” (2009, 146). Žižek argues that as opposed to torture practices carried out in other cultures and nations, which are executed in secret, US army tortures tend to record the prisoner’s humiliation with a camera, making it part of a performance. “The very positions and costumes of the prisoners,” Žižek continues, “suggest a theatrical staging, a kind of tableau vivant, which cannot but bring to mind the whole spectrum of American performance art and ‘theatre of cruelty’” (146).26 Viewed in this light, the excess and theatricality of Gómez-Peña’s barbarians do not seem foreign to American culture.

Nevertheless, the barbarian personas add a second layer of distance from the American “theatre of cruelty.” This distance draws specific attention to the theatrical aspects of US culture. For example, the photo-performances that thematize torture overemphasize the staging of the scene. In the image Abu Ghraib Reenactment, shot in black and white, two men stand next to each other, both wrapped in barbed wire. The man on the left is holding a machine gun, pointed at the other man. The man on the right has a serene facial expression, his eyes closed, perhaps awaiting his execution. He is wearing a shirt full of holes and covered in what seems to be blood, and underneath he is wearing pantyhose—an allusion to the sexual humiliation of prisoners by US soldiers in Abu Ghraib. What strikes me in this image is that neither of these men is looking at the other. They both turn to the camera: the prisoner with his eyes closed and the torturer with his eyes wide open. It is thus an explicitly staged scene, confirming Žižek’s assertion about US army torture that it is performed not simply in front of a camera but, first and foremost, for the camera.

However, there is a crucial difference between the effect of this photo-performance and that of the photos of army torture Žižek describes. The personas in Abu Ghraib Reenactment do not have the same affective impact as recorded scenes of torture. They do not emulate pain, agony, or humiliation but enact the staging of pain and agony. The viewer’s empathy is further diminished by the knowledge that these are not recordings of real torture. As a result, what the barbarians communicate to the (Western) viewer may seem to be this: It is not our fault you cannot identify or sympathize with us. Even if you are not aware of it, you are used to keeping this distance from others in everyday life, because real pain and violence reach you as a spectacular performance. But our staged performance bothers you because we make you aware of your own distance from things or other human beings.

FIGURE 7.5 Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Abu Ghraib Reenactment, 2006. From “The Chi-Canarian Expo” portfolio (original photo in black and white). Photograph by Teresa Correa. Courtesy BRH-LEON editions.

The pervasiveness of the culture of spectacle in our lives does not prevent us from experiencing things as “real.” On the contrary, as Žižek argues, there is an “underlying trend to obfuscate the line that separates fiction from reality” (2005, 147). We do not give up on reality but try to create a sense of reality in everything, without the dangers “the Real” entails. As a result, the taste of reality we get today comes from products, situations, or actions deprived of their substance:

In today’s market, we find a whole series of products deprived of their malignant property: coffee without caffeine, cream without fat, beer without alcohol. . . . And the list goes on: what about virtual sex as sex without sex, the Colin Powell doctrine of warfare with no casualties (on our side, of course) as warfare without warfare . . . up to today’s tolerant liberal multiculturalism as an experience of Other deprived of its Otherness (the idealized Other who dances fascinating dances . . . while features like wife beating remain out of sight . . .)? (Žižek and Daly 2004, 105)

This describes a process that yields “reality itself deprived of its substance”: “Just as decaffeinated coffee smells and tastes like real coffee without being real coffee” (Žižek 2002, xxvi). As a result, Žižek claims, the “twentieth-century passion to penetrate the Real Thing (ultimately, the destructive Void) through the cobweb of semblances which constitute our reality thus culminates in the thrill of the Real as the ultimate ‘effect’” (xxvi–xxvii).

Reality TV is one example of this trend: these shows sell “real life,” but in fact people are still acting, playing themselves. Gómez-Peña’s barbarians bring about the reverse effect: they incite us to see things as constructed, fictional, unreal. They reintroduce a distance between performance and real life—it is impossible to view those personas as real people. Thus, they bring fiction back into our sense of reality. In other words, they do not put the caffeine back into our decaf coffee, but they make us taste decaf coffee as not real coffee.

The barbarian personas make us experience our realities as less than real by refusing to take themselves too seriously. The non-serious theorizing they develop carries significant political ramifications. As cultural anthropologist Johannes Fabian argues in “Culture with an Attitude,” humor, irony, and parody can function as strategies of defiance and negation, which allow us to counter false expectations of congruity in culture (2001, 97). Fabian proposes a strategy of negativity in our approach to culture, which he describes as “a critical mode of reflection that . . . negates what culture affirms” (93). In our theorization of culture, he argues, we need to challenge “those ideas that make us so terribly positive and serious” (98). In the performance of Gómez-Peña’s barbarians, the redeployment of stereotypes turns into such a strategy of non-serious negation. By using reflexivity, irony, and self-deprecating humor, and by “being unserious about culture” (98)—all ingredients of Fabian’s strategy of negativity—Gómez-Peña’s barbarians unsettle the seemingly rational structures of Western society and tease out its irrational underbelly.

The non-serious attitude of the barbarian personas is aimed not only at culture but also at theory. By keeping an ironic distance from themselves, they also distance themselves from the theoretical discourses that could claim them. The titles of photo-performances such as La piedad postcolonial, Hybrid Gang Banger, or Aristócratas nómadas, for example, contain explicit references to postcolonial discourses, theories of cultural hybridity, and (intellectual) nomadism, respectively. The references to popular theoretical concepts in the titles are, I contend, not a manifestation of the theoretical allegiances of “The New Barbarians.” Rather, they constitute a strategy through which they avoid being appropriated by theory—be it postmodern, postcolonial, poststructuralist, or humanist—by making it part of their ironic critique.

By refusing to take themselves too seriously, the barbarian personas avoid reduction to theoretical commonplaces. They explicitly thematize several currently popular issues, including borders, identities, race, gender, violence, the West and its others, the role of the media, and the relation of the margins to the center. Thus, they appear as perfect examples to use for studying multiculturalism, globalization, border crossings, the postcolonial condition, alternative histories, cross-culturalism and (cultural) translation, hybridization, queer identities, posthumanism, and so on. The theoretical references of their performance—complemented by Gómez-Peña’s theoretical writings—are impossible to miss. Surrounded, as it were, by theory, the barbarians make it hard for their viewers not to look at them through a preconstructed theoretical lens.

Do their theoretical allusions make these barbarian personas predictable, convenient, and obedient case studies for theorists? I argue that this is not the case. Thematizing theory can be seen as part of their non-serious attitude and aesthetic of excess. The barbarian personas are not just overloaded with props, makeup, and costumes but also with popular issues, concepts, and theories. The latter are also part of the cultural baggage they recycle. By performing an overload of theory, they point to the oversaturation of certain theoretical concepts and views, which have become buzzwords within self-authenticating theoretical discourses. Thus, by making theory part of their non-serious theorizing, the barbarians plead for a constant revision of theoretical concepts and reclaim the “edge” of theory. The critical potential of concepts is not to be taken for granted, because concepts may turn into empty fashionable terms. Therefore, by not taking theory seriously, Gómez-Peña’s barbarians urge us to take theory more seriously than we often do.27

In borrowing tools from different theoretical “toolboxes,” Gómez-Peña does not commit to a theoretical discourse. In one of his “Activist Commandments of the New Millennium,” he writes: “Be an ‘outsider/insider,’ a temporary member of multiple communities” (2000, 94). This practice of multiple provisional belongings does not necessarily entail lack of true engagement. By shifting alliances and belonging to different communities, we become aware of the blind spots in our principles and discursive frameworks. In this spirit of antidogmatism, it is perhaps slightly contradictory that Gómez-Peña has often formulated his artistic and theoretical principles in the form of commandments and manifestos. However, even in these prescriptive texts he makes sure to insert self-undermining “barbarisms.” Thus, among his “Activist Commandments of the New Millennium” we read: “Question everything, coño, even these commandments” (2000, 93). The same commandments end with a subversive postscript: “P.S.: And one more thing—don’t make the mistake I am making in this text and take yourself too seriously” (94). Moreover, the manifesto of La Pocha Nostra is entitled “An Ever Evolving Manifesto,” which underscores its provisional character (2005, 78).

Although the barbarian personas flirt with different theories of identity and difference, they do not commit fully to any of them. This attitude hints at one of the main tasks of the “new barbarian” they propose: to offer a critique of existing discourses not by seeking to construct a new dominant discourse and, through it, a new center of power but by creating a language able to generate its own barbarisms. Such a language would question and renew itself before its signs turn into stereotypes.

Other New Barbarians

Just as Kendell Geers’s and Graciela Sacco’s installations participate in a transcultural and intermedial network through their title, “The New Barbarians” converses with works that engage with the figure of the “new barbarian.” There are parallels between Gómez-Peña’s barbarians and Hardt and Negri’s “new barbarians,” laid out in Empire (2000). Hardt and Negri’s “new barbarians” are a “new nomad horde,” a “new race” invested with the task of invading, evacuating, and bringing down Empire (213). The authors view the new barbarians as the answer to Nietzsche’s famous question in The Will to Power: “Where are the barbarians of the twentieth century?” (quoted in Hardt and Negri 2000, 213). Hardt and Negri see Nietzsche’s barbarians, for example, in the multitude that brought down the Berlin Wall in 1989. However, the new barbarians, the authors argue, should not only cause destruction; they must also create an alternative global vision. This would be the “counter-Empire,” which the authors identify with a “new Republicanism” (214). Taking up Benjamin’s notion of positive barbarism and his vision of the “destructive character,” they contend that “the new barbarians destroy with an affirmative violence and trace new paths of life through their own material existence” (215).

According to Hardt and Negri, barbaric deployments that can trace such new paths often appear in “configurations of gender and sexuality”: bodies “unprepared for normalization” “transform and mutate to create new posthuman bodies” that subvert traditional “boundaries between the human and the animal, the human and the machine, the male and the female, and so forth” (215–16). In this delineation we recognize the transgressive and posthuman bodies of Gómez-Peña’s barbarians, which accommodate not only different identities but also incongruous life-forms, matter, and modes of being. Among them, we find half-naked cyborgs with machine guns and robotlike masks (Ciborg miliciana); actors in a soap opera with alien heads (Telenovela española); figures in drag with shields, high heels, and Indian feathers, holding dead chickens and supporting themselves with crutches (El chamán travesti, Alianzas aleatorias); and various queer bodies defying borders of normality. Such corporeal mutations constitute for Hardt and Negri an “anthropological exodus,” which is crucial in the struggle of republicanism (read: barbarism) “‘against’ imperial civilization” (215). They conclude that “being republican today” (for them a synonym for the “new barbarian”) means “struggling within and constructing against Empire, on its hybrid, modulating terrains” (218).

Although Hardt and Negri’s conclusion finds support in Gómez-Peña’s barbarians, the two visions are not a perfect match. Hardt and Negri’s project of building a counter-Empire has, in fact, hegemonic aspirations. Through their critique of Empire, Hardt and Negri unwittingly reveal their own imperial project, the “New New Empire,” or, as they call it, “New Republicanism”—a project that, as Mihai Spariosu argues, does not really “offend the sensibilities of democratic Western society” (2006, 92). By contrast, Gómez-Peña’s barbarians do not aspire to replace a dominant discourse with a new doctrine. Rather, they decentralize dominant discourses by assuming a multiplicity of positions and testing several aesthetic and theoretical strategies, without committing to them dogmatically.

Gómez-Peña’s barbarians could also be seen as embodiments of a twenty-first-century version of Walter Benjamin’s barbarian. As argued previously, Benjamin’s barbarians in “Experience and Poverty” share most of the qualities of Benjamin’s “destructive character.” Gómez-Peña’s project differs considerably from Benjamin’s. Each project responds to different social and political realities. In 1933, Benjamin’s barbarians are invested with the potential to create something radically new through destruction of the old, in order to “to make a new start; . . . to begin with a little and build up further” (2005b, 732). Gómez-Peña’s barbarians do not begin with “a little” after having erased the old. They construct their barbarian grammar out of the excess of the existing culture, by devouring and contaminating its saturated modes of expression. In their performance, the existing culture is parodied, restaged, and reinvented.

However, the common denominator in Benjamin’s and Gómez-Peña’s barbarians lies in their readiness to question existing structures and replace them with something new, whether this newness emerges from the ashes of the old (in Benjamin) or from its excess (in Gómez-Peña). Moreover, although Benjamin’s and Gómez-Peña’s projects spring from a different historical moment, they share a similar starting point: the overload of culture, which Gómez-Peña’s barbarians perform and exploit, is also what triggers Benjamin’s proposal for a new kind of barbarism.

The poverty of experience that Benjamin diagnoses emerges from an excess of ideas and styles. People, Benjamin says, “have ‘devoured’ everything, both ‘culture and people,’ and they have had such a surfeit, that it has exhausted them” (2005b, 734). Benjamin seeks new expressive forms to counter this excess. Gómez-Peña exploits this excess and turns it against the culture that has produced it. His barbarians expose the excess of capitalist US culture and simultaneously reclaim this excess in ways that cannot be captured by the norm or the stereotype. Whereas the overload of culture Benjamin describes in 1933 is a sign of bourgeois decadence, in the beginning of the new millennium, Gómez-Peña’s barbarians turn this overload into a force of contestation of dominant narratives. In this way, they propose a new Barbarentum, based not on a destruction of the old (as in Benjamin) but on a cannibalistic aesthetic that devours everything and spits it out in new configurations.

Benjamin’s and Gómez-Peña’s barbarians share an openness to self-contestation. To Gómez-Peña’s motto “question everything, coño, even these commandments” we could juxtapose Benjamin’s principle: “always radical, never consistent” (Gómez-Peña 2000, 93; Benjamin 1994, 300).28 This prevents their positive barbarism from turning into another version of the “old” or the dominant. “The destructive character sees nothing permanent,” writes Benjamin in “The Destructive Character,” and this includes his own methods and beliefs. He “has no interest in being understood. . . . Being misunderstood cannot harm him. On the contrary, he provokes it” (2005b, 542). Gómez-Peña’s barbarians also invite self-questioning and misunderstandings through their “non-serious theorizing.” Safeguarding the openness of one’s own statements or performances becomes an indispensable feature of the new barbarian, either of the twentieth or of the twenty-first century.

From Absence to Excess: Three Ways to Political Art

If Geers’s labyrinth is empty and Sacco’s installation withholds every trace of the other besides the eyes, Gómez-Peña’s barbarians appear full-fledged before the viewer. Yet they are just as confusing as the eyes in Sacco’s work. Although we can analyze the individual signs that each persona comprises, when trying to lead our analysis to a coherent interpretation, we are often at a loss.

The barbarisms that constitute Gómez-Peña’s visual grammar are part of an aesthetic of excess. In stark contrast with Gómez-Peña’s project, Kendell Geers’s Waiting for the Barbarians and Graciela Sacco’s Esperando a los bárbaros adopt an aesthetic of invisibility and suggestiveness, respectively. Compared to Geers’s and Sacco’s works, Gómez-Peña’s barbarians reveal too much instead of too little. However, precisely this extreme visibility and theatricality of their performance discourage the viewer from relating to them as human beings. The inability to relate to these figures, however, has a political function. It compels the viewer to experience the dehumanization that takes place in constructing the other as barbarian. Moreover, it projects the catachrestic character of the designation “barbarian” by suggesting that this name has no proper meaning and literal referent.

Geers’s and Sacco’s works play with traces, absences, or elusive signs. Gómez-Peña’s barbarian bodies are overly representational, so much so that they question the very possibility of representation, seen as an intelligible correspondence between a certain reality and an image of this reality. The constellation these three artworks form through their engagement with barbarism and barbarians is marked by a movement from an aesthetic of absence and invisibility (Geers) to minimal presence and suggestiveness (Sacco) to excess and visual overload (Gómez-Peña). The figures of otherness that emerge through these aesthetic visions—absent barbarians, invisible specters, half-hidden others, and ex-centric new barbarians—cast a critical eye on the barbarians Western discourses have constructed in the past but also in the twenty-first century.

Although the works’ aesthetic visions differ, the critical operations performed by Geers’s, Sacco’s, and Gómez-Peña’s works are comparable. Geers’s and Sacco’s installations show more by showing less: their affective operations are mobilized by the things the viewer can imagine and experience because of (partial) invisibility or absence. Gómez-Peña’s barbarians show less by showing more: despite their semiotic overload, they remain inaccessible and distant and refuse to represent any “real barbarians.” This play between visibility and invisibility, excess and inaccessibility, distance and proximity makes us question the kind of straightforward knowledge our vision supposedly produces. In all three works, what we think we know (and control) by seeing is put in doubt. We simply cannot trust our eyes. Neither the eyes in Sacco’s installation, nor the spectral forces in Geers’s labyrinth, nor the personas in Gómez-Peña’s “New Barbarians” offer us the ease of recognition that familiar faces and objects guarantee.

The explicit political content of “The New Barbarians”—its critique of mainstream US culture—enhanced by the theoretical essays that accompany the portfolios, raises the question of the relation of the aesthetic to the political. Does the work’s aesthetic become an auxiliary means of serving an activist agenda of resistance to the mainstream? Although Gómez-Peña’s barbarians practice a kind of activism through art, it is not so much their political agenda that makes them political art. Their political interventions unravel through the barbarian aesthetic they create. Western imagery is inflated, cut, and pasted in such a way that its own severed parts are unrecognizable yet strangely familiar. The political is thus played out in the tensions they stage between different cultural registers and representational regimes—tensions often suppressed by a “monolingual” culture of consensus. Their political force is in line with Chantal Mouffe’s definition of the political. According to Mouffe, “the political” captures the agonistic dimension that she takes to be “constitutive of human societies” (2005, 9). It describes a “vibrant ‘agonistic’ public sphere of contestation” that acknowledges the “conflictual dimension of social life” as a necessary condition for democratic politics (4).

Gómez-Peña’s, Sacco’s, and Geers’s aesthetic strategies carry political investments. The aesthetic of these works is not a vehicle for an extractable political message but creates political spaces, charged with the kind of agonistic relations that, according to Mouffe, typify the political. Their aesthetic strategies—showing too much or too little—oppose a visual economy of excess to an economy of debt and withholding. Despite their divergent strategies, however, they all resist reduction to illustrations of a theoretical and/or political position. Instead, they become agents of a barbarian mode of theorizing. Their political potential emerges from showing “the kinds of critical thinking that images can make possible” (T. Clark 2006, 185).

Gómez-Peña’s personas enact a nightmarish version of popular images of barbarians. At the same time, as the enigmatic eyes in Sacco’s Waiting for the Barbarians and the spectral forces in Geers’s labyrinth, they may be viewed as the ugly caterpillars that bear the promise of a better alternative to the binary logic of “civilized versus barbarians.” These figures turn the “barbarian” into a marker of ambiguity and confusion. This barbarian challenges “the barbarian” of dominant Western discourses, who poses as the inferior part in a predetermined comparison with a “civilized” standard. The new barbarian is a genuinely comparative figure, functioning in the margins of dominant discourses and inviting open-ended encounters between two (or more) subjectivities, objects, languages, or discourses, foreign to each other.

The confrontation of the viewer with Geers’s, Sacco’s, or Gómez-Peña’s works could also be seen as an instance of comparison, when the viewer’s sense of self and preconceptions are tested against the artworks’ performance. The openness of this comparison entails the risk of reconstituting dominant discourses. Thus, a certain viewer might still fill in the missing gaps of Sacco’s eyes with images of threatening barbarians behind the wooden fences, ready to invade our space. This could reinforce this viewer’s conviction that the borders of civilization should be closed for immigrants. Likewise, Gómez-Peña’s exposure of the internal contradictions within Western representational systems need not have subversive effects on all viewers. As Bhabha argues, internal contradictions always exist and do not necessarily make powerful discourses less effective (1994, 134). Some viewers may perceive the performance of “The New Barbarians” as too “unserious” and estranging to be worth engaging, or as a form of activist resistance that can be anticipated and absorbed by the dominant. The kind of agency “The New Barbarians” assumes might thus end up reconstituting the mainstream. In political art, such risks are part of the unresolved tensions artworks set up, but they are risks certainly worth taking.