Boom and Bust 1971–1981

John Sullivan joined Airfix as Sales Promotion Manager in the summer of 1970 and stayed until November 1973. Educated not far from his new employer at the prestigious Emanuel School in Wandsworth, John originally planned to become an architect, doing particularly well in the necessary subjects like applied mathematics at A-level. However, when he discovered that it would take seven years at a weekly salary of £3.50 before he could practice independently, he had second thoughts.

After National Service, during which he spent a couple of years in RAF Coastal Command (learning a lot about life, as ‘you shared your billet during basic training with dustmen and physicists’), he considered ICI’s Paints Division but, after visiting Lines Bros, was confident his talents could best be used selling toys.

‘I joined Lines Bros in 1960 and started off in their showrooms in the Haymarket and the Water Gardens in Edgware Road. They had their own showrooms – they didn’t bother going to Brighton; they were so big they had their own fair. They had so many brands they did everything, in fact.

‘I joined Airfix because Tri-ang was going bust. They were going into liquidation. I worked with Jonathan Brown in Tri-ang and when he became marketing director of Airfix he head-hunted me to join him there as sales promotion manager. One of my jobs was to find out what was selling and what wasn’t and this entailed going out with the reps. The other main part of my job was sales training. I reported to Sales Director Garth Drinkwater on the sales side and about marketing matters to John Brown.

‘I went out with the Airfix kit reps and the Airfix toy reps around the country. At the time Airfix’s national accounts director was Peter Mason.

‘Obviously the kits were the main thing and it was far more difficult selling games and toys because of all the competition in the market place. I used to go out with the reps and there was a chap, a young chap, in Yorkshire who thought he knew everything. It is very difficult showing people how to sell – I believe salesmen are born, not made – but he thought he knew it all. We had some disastrous experiences. We went to one newsagent who sold a lot of kits (many did then) and this isn’t really so funny, but you get “buying signals” when you sell, and the shopkeeper said, “I need some more of those 19p kits.” And immediately what the rep should have done was do a stock check and make a recommendation. Instead of that he carried on talking about football and by the time he got down to it, the shopkeeper said, “Look, the kids are coming out of school now so you’d better come back another time.” A complete disaster.’

John told me that his week generally consisted of four days out on the road with reps and on Friday he was back in the office at Airfix working on the required admin. He found the job challenging, often driving up to Manchester, for example, for an early morning start. He spent a long time on the road but reckons it was easier on the less congested motorways forty years ago than it is now.

‘We used to have regular sales conferences and at them Garth Drinkwater always believed in role-playing, “pretence selling”, in front of a video camera where you’d have one of the area managers playing the shopkeeper and someone else playing an Airfix sales rep on a visit. I remember one occasion where the chap playing the rep, Michael Caplin, approached the “shopkeeper”, Peter Kelly, saying, “I’ve just popped in to see if you want something,” only to receive the answer, “Well I don’t, so you’d better pop out again!” Michael Caplin then asked, “Are you sure you don’t?” whereupon Pete Kelly answered, “I’ve just told you I don’t, so why don’t you just clear off!” Everyone at the conference was in hysterics, as you can imagine.

John remembers Airfix Managing Director John Gray as a relatively quiet man but says he was ‘very pleasant’.

Airfix had separate reps either selling kits or toys and John was responsible for training both.

‘With kits, all you really needed was a conscientious rep and efficient administration of customer orders and deliveries,’ John told me, adding that he discovered quite often that there were problems with shops not getting what they ordered at the right time.

As national accounts sales director, Peter Mason looked after F.W. Woolworth and all the large multiples as this was big business and of vital importance to Airfix’s revenue stream and commercial reputation. Peter especially loved Airfix kits. When I interviewed Ralph Ehrmann recently, he said of Peter, ‘… he also loved the company.’ Mr Mason died in the 1990s.

John told me that if any rep ‘had the gumption’, they not only did the selling to individual shops, they did the buying too.

‘They would go along and say, “I’ll just see what you’ve got and show you what’s available,” and that was that. Selling to newsagents was really a merchandizing operation. Kits were a bestselling line because they sold all year round and not only at Christmas – a wonderful product that you would see everywhere.’

John told me that kits weren’t a new thing to him. When he was with Triang he sold the famous FROG kits, which, ironically, were made at the Westwood factory in Margate, where Airfix’s current owner, Hornby, is based. ‘In fact, I’ve sold most things in the toy trade at some time in my life!’ he chuckled.

When I asked him what were the highlights of his time at Airfix he immediately answered, ‘Having a good laugh with Sue Wright. I had a lot of fun and I felt I achieved a lot of things, but I don’t think there were any particular highlights. I was only there a couple of years. It was OK, part of my life, but not a huge part.

‘I liked Garth Drinkwater. He was very laid back. Very comfortable, a good speaker. A very popular man, I think. He had an air of authority about him but was very relaxed. I liked him.’

When John joined Airfix in 1970 it would not have been unreasonable for him to think he was saying goodbye to the world of Tri-ang for ever. However, such is the interconnected nature of the British toy industry that I doubt he was too surprised to see his past catching up with him when, on 23 December 1971, Airfix Industries acquired Meccano-Tri-ang!

What Frank Hornby had founded as Mechanics Made Easy in 1901 turned out to be one of the few parts of the recently collapsed Lines Bros empire still considered commercially viable. The price paid for it was £2,740,000, which seemed a bargain for such an iconic toy brand.

Dinky, an almost equally famous toy brand, was included in the Meccano purchase. This made sense because both Dinky Toys and Meccano were then manufactured at the famous Binns Road factory in Liverpool. Airfix soon dropped the Meccano-Tri-ang moniker, instead choosing Meccano Ltd as the operating division’s trade name.

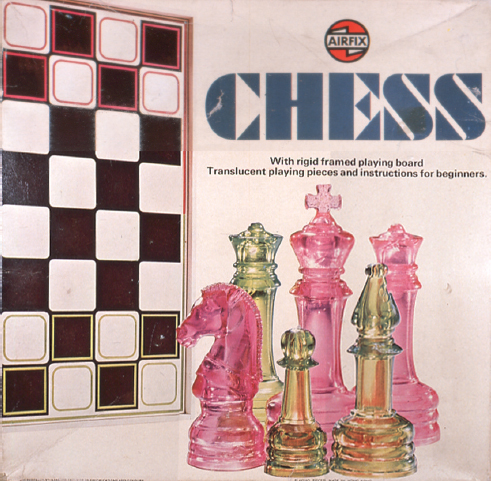

Rare and, to my eyes, actually quite stylish in a Department S kind of way – an Airfix plastic chess set from the early 1970s.

These were heady days at Airfix. In 1971, the company received a Queen’s Award to Industry for export achievements. That same year, Kingston Plastics, of West Molesey, Surrey, was absorbed into the growing brand family. Also in 1971, Airfix Footwear was reorganized with purpose-built factories supplementing the efforts of outworkers, who, given instruction and training, assembled the supplied parts of shoes at home.

‘The products coming from the enlarged Airfix Footwear factories are a delight to the eye with their colours and elegant shapes,’ Ralph Ehrmann said at the time.

Indeed, Airfix – Britain’s most famous name when it came to plastic – was determined that this long derided product was seen with fresh eyes.

‘Plastic can be a quality and even aesthetic material in its own right and not just an inexpensive substitute,’ chimed the August 1973 edition of Airfix News, the company’s house newsletter. These not unreasonable words related to the recent association between then, plain old Terence Conran, chairman of Habitat, and Airfix’s Crayonne brand.

As another example of what Ralph Ehrmann called ‘a year of rapid expansion and record results’, Airfix had joined forces with Conran to ‘design, manufacture and market products that fulfil “the highest standards of design quality, function, flexibility and value for money”. To this end the association with Conran provides a unique and powerful combination of design, moulding and retailing skills spanning twenty-five years of experience.’

A brand new product range, Input, was revealed to coincide with the announcement.

‘Designed – and named – by Conran and made at Airfix Plastics’ Sunbury works, the Inputs are based on a simple concept: that in every home there is a multitude of items that need somewhere to be put,’ was the pretty straightforward raison d’être behind these natty tubs and containers made from multicoloured and highly polished heavy duty ABS plastic. David Sinigaglia, the managing director of Airfix Plastics, saw the Crayonne venture as a way of ‘upgrading the whole image of plastic,’ believing that the British were changing their buying habits. In Airfix News he even went as far as saying that high quality, well designed plastic furniture had a big future.

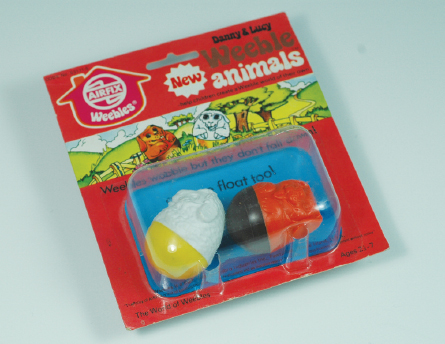

Weebles in blister pack.

‘Weebles wobble but they don’t fall down …’

Weebleville Airport hangar and aircraft.

Weeble Cabin Cruiser from 1973.

There was lots of other exciting news at Airfix in 1973. Declon Foam Plastics moved into the hi-fi market with the development of a new process for cutting foam for speaker fronts. A new division, Airfix Interior Designs, part of Airfix Plastics, began working with European manufacturers such as Bilumen of Milan to market a wide range of larger plastic products like television tables, chairs and even umbrella stands. The Littlewoods Stores Group placed a substantial order for trays for use in the deliveries of bakery products and they had ‘more than ninety outlets throughout the UK’, claimed Airfix’s PR Department.

But this book is really about Airfix Toys & Games and Airfix Arts & Crafts and, as you would expect, there was plenty happening in these areas in 1973. Probably the biggest news in the toy line was the arrival of Weebles, originated in US toy giant Hasbro’s Playskool Division in 1971 and now manufactured under licence by Airfix in Wandsworth.

Actually, Airfix didn’t just re-box the American product; they re-evaluated it and redesigned it, ironically improving the look and durability of the toy in an effort to, initially, at any rate, save money! American Weebles were smaller but each character’s features were printed on a separate component and viewed through a transparent top half. The bottom bit was solid and contained the weight, preventing the little creatures from falling down. Airfix Weebles featured moulded details on a solid top half.

There were five family members – granny, mother, father, son and daughter. The children were of a slightly smaller size than the adults and the whole family was available in a window display pack. Weeble accessories included: a double-decker bus with the driver wearing a cap – there was room for three more Weebles on the top deck; a police van with driver; a fire engine with fireman; a Weeble house, which included three rooms and a garage; a Weeble playground set; and, my favourite, a Weeble airport hangar and as many as three different types of aircraft to park inside. There was also a Weeble harbour, yacht, cabin cruiser and dinghy with outboard motor, and even a water-ski set.

Mum and son (with iconic 1970s’ haircut and great threads) playing Airfix’s Got A Minute. Released in 1975, this was a neat word game played against the clock, or, more properly, the egg timer. Remember, this was at a time when more cerebral games such as Invicta’s Mastermind were all the rage. (From the V&A Museum of Childhood archive. Copyright Airfix)

Airfix had high hopes for Weebles and they had committed a substantial investment to the products’ success. By mid-summer 1973, John Gray, Airfix Products’ managing director, had already travelled more than 100,000 miles to negotiate export orders for Weebles. Airfix News said that the Wandsworth factory was now in full production of Weebles and that demand from overseas customers was increasing steadily month by month. A photograph of John Gray showed him and Mrs Gray energetically loading carton upon carton of Weebles into the boot of his Jaguar as he prepared for an imminent sales trip to France, Germany and Italy.

When I consider what kept us kids happy in the 1960s and 1970s, such as endlessly chucking flimsy expanded polystyrene model aeroplanes like this Airfix Same Day Flyer, and compare our pursuits with those of today’s teenagers, festooned with iPads, iPods and smart phones, it’s pretty clear I was born too early!

Alice shows her delight at completing a snowman and teddy bear from her Airfix Round Knit set.

An assortment of Airfix Craft Kits from the mid-1970s. Everything a little girl needed all in one cheap package. Inspired!

In fact, Airfix had high hopes that they might experience record sales for Toys & Games in 1973. ‘Airfix Games are a Sell-out’ was the headline of a promotional piece that year showing Airfix toy designer David Pagani with three bestselling lines. They were: Pounce – a fast new word game that can be played by the whole family; Big Cheese – an ingenious two-person game that involves players manipulating a mouse carrying a marble up the side of a holed cheese; and Don’t Let the Leaves Fall – a family action game that was designed by eleven-year-old Mandy Averillo as part of a nationwide competition organized by Magpie, Thames Television’s popular children’s programme.

Arts and crafts also enjoyed top billing in Airfix News in 1973. In bold type beneath the headline ‘Big Build-up in Arts & Crafts’, it said:

Whether it’s Mothers Day, Christmas or a birthday, there’s no limit to the imagination and resourcefulness of young children who make their own presents. For this reason Airfix Products is continually developing and expanding its range of arts and crafts, thus offering youngsters countless opportunities to develop their own particular skills and interests.

Backing up this bold claim, in 1973 Airfix put their money where their mouth was by releasing a new range of twenty-four Craft Kits – especially for girls. There was a photo of the finished item on the front of each pack and enough material within to complete either Paper Flowers, Plant Pot Holder, Napkin Rings, Egg Cosies, Mobile, Pin Cushion, Greetings Card, Pipe Cleaner Figures, Printing Set or fifteen other similarly crafty items.

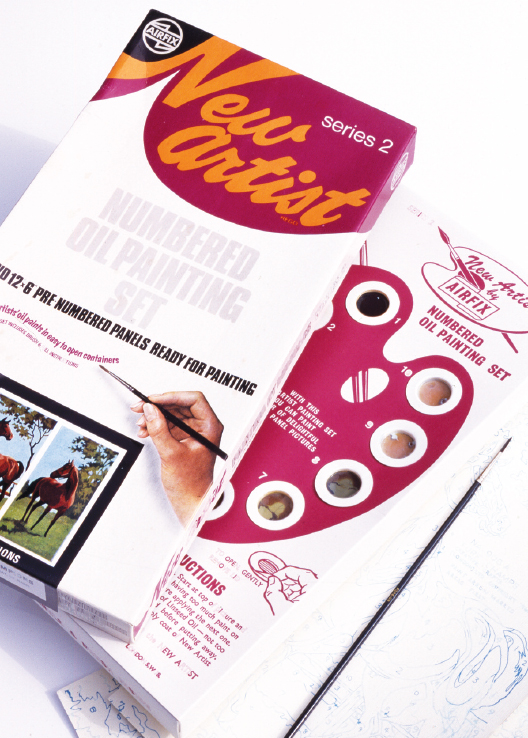

The New Artist Painting by Numbers range was extended with the addition of the Pet Set, a range of six pictures depicting cute pets such as a hamster, for those living in a tower block, right up to a horse for those young gals residing in the Home Counties.

Felt Craft, Bead Craft and even Sandpaper Art were new additions to the crafts range. Sandpaper Art, a fascinating craft line, contained sandpapers, carbon paper and four different patterns on sheets of paper from which youngsters could trace onto the sandpaper using carbon. Having taken your pattern and traced through the carbon onto the sandpaper, ‘you are left with a drawing that you can complete with any variation of colours,’ readers were assured.

Mary Wright, the Airfix Arts & Crafts product manager and the driving force behind the range, was photographed standing behind a table containing these new products. In fact, even more than those described above could be seen in the photo. There was also Foil-Craft and Free-Style, which came with fewer instructions and twenty different colour paints that could be used just as the painter wished but broadly in line with a half-sized colour illustration provided with the set.

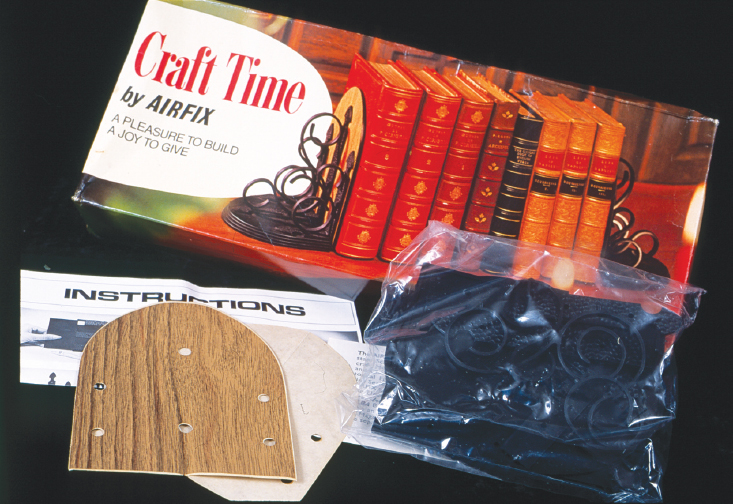

Airfix Craft Time Plant Holder. The ubiquitous Fablon sticky-backed plastic can be seen in the box, as can the oh so popular wood grain effect!

In October 2011, I had the good fortune to interview Mary Wright at her home in Cheam. I was keen to know when she joined Airfix and what she was doing before she went to Haldane Place.

‘I joined Airfix early in 1970 and left at the end of 1976, prior to the birth of my first son,’ she said, ‘though I did go back in from time to time, including one memorable occasion to the Toy Fair at Birmingham with my thee-month-old child. There was a rep sitting opposite who had brought a live chimpanzee on board – very surreal; the animal was used to promote a new toy monkey.’

However, working with Airfix and raising a child weren’t really synonymous, she told me.

‘I had studied art, industrial design and furniture design at London’s Central School of Art and Design in Holborn, finishing in July 1969. Because it was the bulge year, with lots of kids who had been born just after the Second World War looking for work, it was not easy to find a job, certainly in my field, because my final project was toy design.

‘I came out and was frankly looking for anything. I don’t know if I applied directly to Airfix or went there via an agency. At the time Airfix were looking into licensing toys from Hasbro. They dealt with people like Ned Strongin, the well-known independent toy designer who produced a lot of toys and games for Hasbro. At the time I joined Airfix John Gray would have meetings with Ned, who had flown over to see him to discuss all sorts of toy and game ideas. John Gray was not very good at visualizing things, so I was employed to sit in on these and interpret what was discussed – not take minutes, but actually draw what was proposed.’

For the uninitiated, Ned Strongin, who died at the ripe old age of ninety-one in April 2011, was a legend in the toy industry. With Howard Wexler he was the co-creator of the classic game Connect Four, which was developed at their business, Strongin and Wexler Corp. He worked with Airfix on several toys and games but is most famous as being the inventor of the inimitable Weebles.

Mary told me that at the time she joined Airfix the company rarely developed its own toys, preferring to manufacture items under licence. The crafts were all from Craft Master and all the Painting by Numbers sets were shipped in from them in America.

New Artist Painting by Numbers – hugely popular in the days before video and PC games conspired for the free time of youngsters.

Initially, Airfix simply wanted to increase market share by selling construction kits to girls, not just their traditional customer base, which comprised mainly boys. This was why the company went to great efforts to make its 1:12 scale Historic Figures range also appeal to girls, including replicas of Joan of Arc and show jumpers who looked mysteriously just like the young Princess Anne, as well as an extensive range of life-sized garden birds in their range.

‘But they realized that there was a much larger age group area available,’ said Mary. ‘Not just the people who made kits but those who appreciated Airfix as a brand known to deliver good quality. The first thing they thought they could introduce to this new market was pre-school toys and then games. Almost everything Airfix produced was either licensed from Hasbro or via Ned Strongin. The games he’d devised were often manufactured by Hasbro anyway.’

Eleanor studiously applies the finishing touches to her 1:12 model of Queen Elizabeth I. To make this range even more appealing to girls, in the late 1970s the models were retooled and added to the less involved ‘snap ‘n’ glue’ range.

In its never ended quest to encourage girls to construct plastic kits the firm introduced a variety of famous females to its popular range of 1:12 figures. This Airfix press shot shows Anne Boleyn, ‘One of the most romantic and tragic figures in history’, wrote Sue Wright, Airfix’s press officer, on the accompanying release in 1974.

Mary worked at Airfix out of expediency because she simply needed an income. At first she worked there temporarily – she says she may even have started as a filing clerk.

‘They soon became aware that I could draw,’ she told me, ‘and understood that I knew what to do in terms of design. As time went on I became involved with the repackaging of Hasbro items and after that we started to expand the Arts & Crafts lines by doing our own pictures and crafts.’

Until Mary joined, no one managed the Airfix Arts & Crafts range, it being a simple re-badging process as Airfix repackaged Crafts Master Corporation products, replacing the US company’s logo (which featured a CM monogram in front of an artist’s palette complete with paint brushes), along with Airfix’s familiar scroll.

When Airfix included a 1:12 show jumper in their range in 1975 they were accused by some of modelling the figure on Princess Anne, who had won a silver medal at the 1975 European Eventing Championship and was about to compete at the 1976 Olympic Games in Montreal. However, Press Officer Sue Wright’s release, which accompanied this studio shot of the new model, simply said, ‘One for the ladies – a superb model of a showjumper’, and made no reference to HRH at all!

Airfix Pin Head game from 1969.

It didn’t take long for Mary to begin adding home-grown products to the Arts & Crafts range. Soon she was either commissioning new artwork or adapting existing illustrations. Whilst there was no licence involved, as there was with the imported Crafts Master Paint by Number sets, artists’ royalties still had to be paid for any externally produced material.

From 1969, Airfix Craft Time book ends – ‘A pleasure to build, a joy to give.’ Not so the delightful wood effect stickybacked plastic that came with the kit. Such coverings were all the rage in the 1960s.

Not only did Mary produce Glitter Packs as a home-grown, licence-free product, she actually illustrated the two pictures in each of the twelve packs, which featured subjects as diverse as Elizabethan Times, Camel & Lion and Knight & His Lady. So Airfix certainly got a bang for the buck as far as the salary they were paying her was concerned. Apart from Airfix maximizing the output of their managers, however, this fact also demonstrates the creative opportunities available at Airfix back in the day. This multi-tasking makes it easy to understand why so many ex-employees claim that the fact that they could be so closely involved with every stage of a product was one of the most rewarding aspects of working for Airfix.

Mary also told me that she would make models of her proposals, drew any conceptual sketches and costed out the required materials before taking them in to show John Gray to get his approval. Before things proceeded at full steam, however, a few samples would be made and tested on the children of friends and employees to gauge the youngsters’ reaction before Airfix committed the funds to production.

‘This process, from A to B, would probably take a year,’ said Mary. ‘You were always working on an annual cycle.’

In the time Mary was at Airfix the amount of ‘own brand’ products grew significantly. Previously, every Painting by Numbers picture was imported from Craft Master in the US. Now there were not only new, British centric Painting by Numbers pictures, there were a host of fresh craft items besides.

Alongside Craft Master originals in the New Artist range, such as Circus Ride, Early Blooms and Tiger Kittens, there were new home-grown subjects such as Tug & Sailboat, Rupert Bear and London Street Sellers. In New Artist Series Five, which included one large 15ins x 8ins picture and two 6ins x 8ins miniatures on the same theme, Covered Wagon was joined by Woodland Cottage. Series Six pictures were even larger, being a substantial 24ins x 18ins picture, and here Mary introduced Inland Waters and Countryside to sit alongside Murmuring Pines and View of Holland.

As far as licensed products were concerned, Mary also oversaw the introduction of Dr Who into the New Artist range, together with Hugo the Hippo, a popular Hungarian animated film co-produced in the United States by no less an operation than Brut Productions, a division of French perfume company Fabergé.

Although Weebles were a US import, Airfix greatly enhanced the property, just like Britain’s Palitoy did with Action Man, formerly Hasbro’s GI Joe. There is general consensus that, UK Weebles being bigger and more robust than their cousins from across the pond, they were a far superior product. It’s hardly a surprise that Mary’s division produced a series of twelve New Artist Weeble Water Colour Stories, each pack containing six Weeble pictures to complete a tale. Though just how the tales of Daddy & Willy or Fireman & Willy unfolded is lost in the mists of time …

Pin Pictures and Cotton Craft were two home-grown ranges that could only have existed in the 1970s. Cotton Craft was a kind of three-dimensional Spirograph drawing, consisting of winding different coloured cotton threads around a series of neatly arranged pins. I wonder how many youngsters persevered to complete really complex pictures like The Windmill or Elizabeth I (it must have been as easy to embroider the monarch’s ruff in antique lace as it was trying to negotiate the intricate web of pins and thread required to recreate the picture on the box on a 15ins x 11ins black flock base), and how many, or how many of their parents, cursed when they stepped on an errant pin lurking in the weave of a shag-pile carpet …

Kids had to up their game again for Super Pin Pictures, another innovation of Mary’s. This new series combined the techniques of Pin Pictures and Cotton Craft and featured the addition of ‘sequins, paper discs, foil and cotton’, as if things weren’t difficult enough!

Being too busy managing the new Crafts Division, Mary rarely illustrated new Painting by Numbers artworks herself. ‘People like Sue and Graham would come and paint what I wanted them to do,’ she said. More about Sue and Graham later.

Any work produced in-house was also obviously subject to a buy-out with no royalties payable to external artists – another distinct commercial advantage.

‘Freestyle’, billed perhaps rather disingenuously as ‘A totally new idea in oil painting’, was one of the ideas Mary introduced, and unique to Airfix. Freestyle was really painting by numbers without the numbers. ‘Painting is a means of self-expression,’ read the catalogue, ‘and Freestyle painting is a step towards this end. This is a painting set that is quite different because it allows you to paint the way artists paint in a style and treatment that is entirely individual.’ This wasn’t entirely true as purchasers still painted over the top of a pre-printed outline sketch. But, to be fair, although they followed a colour guide painting on the box top, how they executed pictures like Swiss Valley, which showed a carthorse hauling a load of cut logs in the Alps, or Lowland Country, a kind of sub-Constable rural landscape, was (almost) entirely up to them.

‘The artist I commissioned basically worked out a charcoal drawing and you worked out the colour scheme you wanted to use,’ Mary said. ‘It wasn’t painting by numbers, it was painting on a drawing and they were the first craft items that I did.’

Colour Craft, where modelling clay hardened without the need of a kiln and included pre-formed clay coils that could be used to make pots and even a puppet (the stick, string and all the other components needed to bring the puppet alive were also included in the box), was another of Mary’s innovations. As was Colour Craft, which captured the zeitgeist for making brooches, pendants and key ring tags, die-cut shapes that could be painted with a variety of special colours in a medium that dried to an enamel-like finish.

John Gray was Airfix’s managing director throughout Mary’s time there. ‘I know a lot of people found him difficult,’ said Mary, ‘but I always got on really well with him. He was dynamic, wanting to do things yesterday, but because I used to work quite fast we got on really well.’

Mary told me that she also got on particularly well with Frances Sharman, John Gray’s secretary, or ‘gate keeper’, as Mary called her. ‘Get to know Frances and you could get to see John,’ she said.

‘At the beginning of my time at Airfix there was hardly any Arts & Crafts, it was Toys & Games, and I was doing the packaging for them. I would work on the photo shoots and the design mechanics for packaging required for it. This is actually quite specialized because if you’ve got a wobbly toy that goes into a box, you’ve got to make sure it doesn’t break before it gets to the customer.’

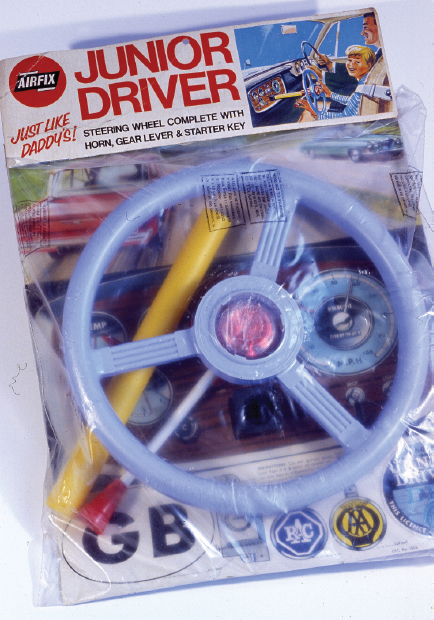

Mary remembers Airfix making few of their own vintage toys when she first joined. Except, that is, for Junior Driver, which she said was a toy that went on forever.

‘When I arrived Airfix certainly wanted to go all-out for pre-school toys and especially the range of Weebles, which they had just imported from America.’

Mary told me that although Arts & Crafts was distinct from the Kit Division, she did work with two people from the department upstairs, liaising with John Harman and Joe Chubbock, model makers who made the original models and dioramas used in kit catalogues. ‘They then did anything I wanted, [and] made it all up – they were really nice people,’ she recalled.

Other than get John or Joe to construct anything in 3-D she might have required, Mary had little to do with the Kits people. However, like everyone else I’ve met who worked at Airfix in Wandsworth, Mary remembers the atmosphere was good and said that sometimes those involved with the Kit Division would simply drop in for a chat.

Airfix 1978 Arts & Crafts catalogue. The cover graphics had been imaginatively executed in Mary Wright’s new Colour Craft Clay product.

John Gray takes centre stage at an early 1960s’ press launch of Airfix’s Wacky Wind-Ups. Ralph Ehrmann (right) and fellow executives look on.

‘I just enjoyed being there and the people I worked with. ‘Airfix was very “buzzy”’, said Mary. ‘I used to travel quite a bit. I’d go to Chicago; I’d go to Nuremberg, and all the other toy fairs. I would go to visit Ned Strongin in New York and stayed in his home on Long Island. He was a very nice, avuncular man. He used to encourage designers and oddballs to come in to see him with new ideas. Then he would take them on board and sell them to people like us and Hasbro. He was just a really nice man. He had a whole team of people sitting in an office just brainstorming ideas for new games. It was hysterical. They were typically very intense young men who were just trying to think up the next new game, the next Big Ear.’ (Big Ear was the very successful Airfix game from 1974 that required competitors to ‘put on a Big Ear, clip on your hook and join the fun as you and your opponents tangle and race to pick up the kinky links.’)

Junior Driver. Alright, Sonny might be sitting in the front (how else would the rubber sucker attach to a shiny surface?), but at least he’s wearing a seat belt!

Mary told me that Airfix didn’t only accept ideas from professionals like Mr Strongin and other people with a proven track record in the particularly competitive field of toy design. Sometimes Airfix saw individual inventors, eager newcomers keen to pitch their big idea to a famous British brand.

Junior Driver demonstrated the fun side of motoring: steering the wheel and honking the horn. Responsibly, Airfix also revealed the downside of driving. Parking meters were first introduced on 10 July 1958, and this very rare Airfix money box was produced shortly afterwards.

‘They were usually a little strange, like a lot of toy and games designers seemed to be,’ Mary recalled. ‘But it was mostly games that were sent in. Although, to be honest, most new ideas came from Ned Strongin’s brainstorming studio in New York.’

Though it’s a long time since she worked there, Mary has fond memories of Airfix. Like so many ex-employees I’ve met over the years, it is clear that working for this famous brand imbues a particular kind of camaraderie. It really was a band of brothers … and sisters.

‘My time at Airfix was good. Everybody would chat to everyone else. John Edwards and Jack Armitage would always be in and out. John, for example, was one of the nicest people you were ever likely to meet. He had a wicked sense of humour and was a real Goons fan.’

Mary told me that often John would pop his head around the door and make silly noises. Now I knew that he was responsible for revolutionizing the accuracy of Airfix model aircraft and I even discovered something of his clandestine duties of making models of Soviet military hardware in occupied Berlin, but I never knew he could pass off a mean Eccles, Bluebottle or Neddie Seagoon! ‘Of course, we fell about laughing,’ Mary smiled in recollection.

‘Working at Airfix was tremendous hard work,’ she continued, ‘but very rewarding and really good fun. The things I found terrifying initially, but in the end proved to be fantastic because you end up on such a high, were sales conferences. There you had to stand up in front of all the reps and describe all the craft items you had made, telling them why they were so good and why they would sell so well in the shops. I would set the stands up and you would be working all hours but it was tremendous fun.’

Mary said that the principal toy fairs where she would exhibit her new products were the ones at Brighton and Nuremberg. The sales conferences she initially found so daunting but quickly mastered were always traditionally held in Eastbourne, further east along the coast from Brighton.

I asked Mary if, considering her design training at one of Britain’s top schools, she ever coveted moving across, perhaps, into the Crayonne Division, which was even beginning to produce Melamine items designed by Terence Conran from its plant in Sunbury.

‘No, I was very happy where I was,’ she quickly answered. ‘I had always made things, so working on craft things was very enjoyable. The toy I designed at the Central School for my end of year piece was a sit and ride vehicle for children, a type of item Airfix never produced.’

In fact, Mary’s ‘toy’, actually a versatile play vehicle, was designed to such a high standard it featured in the September 1969 edition of Design, the Council of Industrial Design’s seminal monthly publication. Designed by the then Mary Dingley and aimed at three- to four-year-olds, her stylish yet practical articulated ride-on and trailer was manufactured from blowmoulded polypropylene clipped to a mild steel tube frame and occupied pride of place amongst a selection of work by final year Dip AD students.

There was incredible closeness at Airfix. ‘Even people from the shop floor would know who you were,’ said Mary. ‘One of the Craft Kit ranges involved making pictures from bits of sprue and I would go down and rummage in the plastic sprue packets and buckets of plastic granules.’

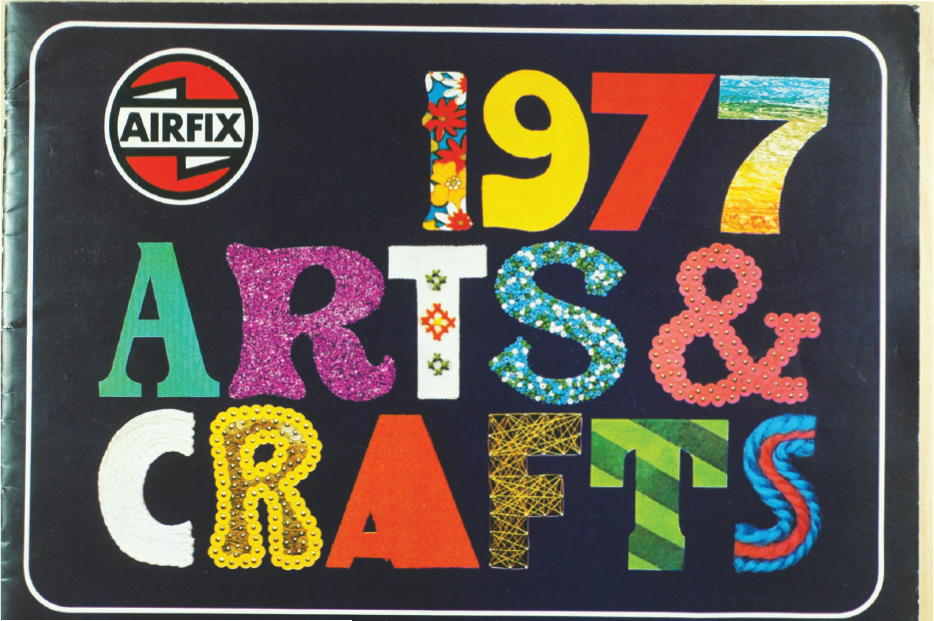

The first dedicated Airfix Arts & Crafts catalogues were produced during Mary’s tenure. ‘We used to use a photographer called Norman Harvey,’ she told me. ‘He was a super chap and we tried to think of different ways of treating the front covers. On one of these he smeared Vaseline over his camera’s lens to accentuate the sparkling lights featured. Great fun!’

Airfix steadily upped its game regarding promoting products and by the mid-1970s, supporting each product line with catalogues was not enough, regardless of how good Norman Harvey’s photography was.

With Airfix now firmly in the big league and developing so many items under licence from US giants like Hasbro –most notably Weebles – there was a concerted move into TV advertising. Ironically, even though plastic kits were and still are the Airfix cash cow, advertising spend was not directed towards them but Toys & Games and Arts & Crafts. Kits more or less sold themselves and whatever advertising Airfix did need was more or less taken care of by a combination of their own adverts and features in Airfix magazine (one of the most successful affinity magazines of all time) and by Airfix buying space in Scale Models and Military Modelling. These three publications reached virtually 100 per cent of the market.

Nearly 500 entries were received for a Black Beauty Painting by Numbers competition sponsored by Airfix in Today’s Guide, published by The Girl Guides Association. The picture shows judging in progress at the Girl Guides London HQ. Left to right: Jean Rush, managing editor of Today’s Guide, David Burrage, Airfix’s PR officer, Mary Wright, Airfix Arts & Crafts’ product manager, and Lady Baden-Powell, Deputy Chief Commissioner of The Girl Guides Association.

It should be noted that at around this time Lesney, owners of the Matchbox brand, had just decided to enter the plastic kit market. Although their early kits were somewhat derided by purists because of the ‘gimmick’ of multicoloured sprues and for significantly deep trenches representing the tiny gaps between panels, Matchbox kits seriously challenged Airfix’s hegemony in this field.

Airfix Products directed a massive £250,000 towards advertising in 1974, with the first of three new Weebles commercials being broadcast nationally in April that year. £150,000 was directed towards additional commercials for Big Ear, Don’t Let the Leaves Fall, Roundhouse and Flight Deck.

Airfix 1975 Toys & Games catalogue.

Airfix 1977 Toys & Games catalogue.

By contrast, only £25,000 was spent on kits. ‘The company is continuing its advertising to the kit market by extensive appearances in modelling enthusiasts’ press, boys’ comics and service magazines,’ an Airfix press release claimed.

It seemed Airfix were getting it right, though. The company claimed that the 1974 British International Toy Fair in Brighton saw a 300 per cent increase in orders compared with those received following the same event the previous year. There was similar good news following the other big toy fair at Nuremburg, where orders were up some 200 per cent.

Chairman Ralph Ehrmann said that the record sales matched the Airfix Group’s highest ever investment in the future. ‘Last year we invested more than ever in new buildings, new machines, new moulds and new designs, so that once again we can look forward to creating new records during the coming year,’ he declared.

Mr Ehrmann was quick to recognize the efforts of everyone involved in this development and expansion during the difficult months up to March 1974, when an Arab embargo on crude following America’s support for Israel in the Yom Kippur War and the simultaneous UK miners’ strike restricted the commercial use of generated electricity to only a few days a week.

‘The short-time working imposed upon us by the three-day week, of course, created hardship for all at every level in the Group by making their daily tasks more difficult and complicated,’ he wrote. ‘Whilst the lost ten weeks left their mark on our results, which should have been even better, we must all be grateful to all employees of the Group for the extra efforts they made in order to maintain production at the levels achieved.’

Sue Wright, Airfix’s press officer, plays mother in this studio shot for the company’s 1974 release, Big Ear.

Airfix’s cherry picking of the Meccano business from the remnants of Lines Bros appeared to be paying off too. Meccano Multikit, a new way of packaging Frank Hornby’s iconic strips of perforated steel and pieces of turned and milled cogs, wheels, sprockets and, of course, nuts and bolts, so that youngsters could make a simple but complete metal model straight from each box, was launched in 1973. At the 1974 Brighton Toy Fair, Meccano Multikit was voted joint second in the Boys’ Toy of the Year section – no mean feat considering the toy had only been on the market for six months.

‘We began deliveries to the trade last August,’ said Doug McHard, Meccano Ltd’s marketing director, ‘and in only three months sales had outstripped our estimated production budget for the whole year!’

Mr McHard reckoned that Multikit revealed the hidden qualities of Meccano in a more effective way than ever before.

‘This is proved not only by the tremendous sales of Multikit,’ he went on, ‘but also by the fact that it is being demanded by children. In the past Meccano has tended to be bought for children on their parents’ initiative.’

No doubt the addition of full-colour, step-by-step photographic instruction books and sheets of self-adhesive stickers made Multikits appealing to the average kid and not just to budding George Stephensons.

Airfix hadn’t been slow to develop another famous brand they had acquired with Meccano. The 1:25 scale Dinky Ford Capri 3000 GXL was Britain’s first die-cast toy in that scale. Just how much bigger it was than existing models was demonstrated by an Airfix press photo of eighteen-yearold Dinky Toy assembler Shirley Abbot of Anfield holding the new model in her right hand while cradling a more traditional 1:42 scale Capri in her left.

Perhaps the biggest Meccano news, however, was Airfix’s announcement in 1974 that they were to challenge North America’s dominance of the big steel toy market with the launch of six new chunky MOGUL models. These comprised the Tractor Digger, Articulated Tipper, Dump Truck, Mobile Crane, Tractor with Trailer and Army Truck.

Introduced as a direct challenge to Minnesota’s Tonka Toys (incidentally, did you know that the name Tonka was chosen because it was the Dakota Sioux word for ‘great’ or ‘big’?), Meccano MOGULs were designed by Ogle Design, the team behind the Reliant Scimitar and the classic Bond Bug. One paragraph, and two things you may have never known. How good is that?

It was hoped that after playing with one or more large MOGUL vehicles, youngsters might develop a fondness for steel toys and then migrate towards traditional Meccano. However, despite being made from the same basic material as its more famous predecessor, the MOGUL range could not be manufactured using the existing plant at Binns Road and Airfix had to invest £160,000 to install the machines required to produce the larger heavygauge steel pressing required.

‘You may call it optimism,’ said Norman Hope, Meccano Ltd’s managing director. ‘But I don’t think it will be long before the MOGUL name is as well known in steel toys as Meccano and Dinky in their own particular spheres.’

In 1975, Chairman Ralph Ehrmann celebrated twenty-five years of service to Airfix. He thanked everyone at Airfix who had helped him since he joined, singling out John Gray, who joined in December 1949, three months earlier than he had. ‘We have worked closely together ever since,’ said Ehrmann, ‘and we share memories of the old days together.’

Ralph Ehrmann welcomed Mr Friedrich Podey into the group, who as boss of Plasty GMBH had been Airfix’s German partner since 1954. A long-time collaborator, Herr Podey now bought Plasty’s Petra doll, one of continental Europe’s most successful toys, into the Airfix fold.

Another new addition to the Airfix group of companies was Pedigree. Located in Wales at Merthyr Tydfil, Tri-ang Pedigree – famous for prams and wheeled toys – was another remnant of the old Lines Bros empire. Since Lines Bros’ collapse in 1971, Pedigree had struggled on under consecutive owners, watching as many as five of its factories mothballed around it as it did so. The labour force had dwindled from thousands to a mere 400. But, with Airfix’s help, the famous range of pedal cars, toy tractors, rocking horses, trikes, dolls’ prams and even real prams was given a new lease of life, as well as a £500,000 cash injection that Tri-ang Pedigree Managing Director Mark Radcliffe was to administer under the supervision of John Gray, now Chief Executive of the Airfix Toy Division.

As every toy collector will confirm, the most collectable items are those associated with successful TV or film franchises. The prices reached today for original, mint and boxed examples of vintage 007, Thunderbirds or even Star Wars toy merchandise are equivalent to the gross product of many small countries. Decades ago, before the recent craze for such items, Meccano Ltd’s Marketing Director Doug McHard appreciated the value of toys linked to broadcast productions or new film releases.

‘Television character merchandise has done a great deal for the toy industry in recent years,’ he said. He wasn’t far wrong, because some of the Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet and UFO toys already in Dinky’s range already outstripped the sales of most other toys produced by the brand. And now, yet another Gerry Anderson sci-fi fantasy series was to be immortalized, when Dinky released a model of the Eagle Transporter from Space 1999. This was soon followed by the release of the Eagle Freighter (you remember – the one with the cylinders of hazardous waste suspended beneath its geodetic fuselage structure).

As this ad from the 1970s shows, Triang had joined the Airfix family during this decade.

Airfix had never done very much in the way of merchandized products. In fact, apart from a few James Bond kits and the venerable Angel Interceptor from Captain Scarlet, released as long ago as 1968 and at the time of writing now back in the range, there wasn’t much at all. In the mid-1970s at least, fans of Space 1999 could buy two Dinkymodels as well as Airfix kits of the Eagle Transporter and the Hawk Spaceship.

Airfix doubled their advertising spend from the previous year, committing £500,000 on TV advertising alone in 1975.

‘As it is quite likely that a lot of our shareholders will not see these advertisements, which are screened in the afternoon and early evening, we show here stills from the six commercials,’ read some marketing editorial next to a film strip featuring stills from the ads in question.

One of the ads was for Magic Miniatures, a neat way of sharpening up – and shrinking – a 10ins x 8ins Painting by Numbers picture down to a crisp, but tiny, 3ins x 4ins masterpiece simply by popping it into the oven. ‘I have this wonderful idea for creating masterpieces that will fool the masters themselves,’ uttered a dotty professor in a new thirty-second TV commercial.

Another ad was for the then new – and now legendary, but perhaps for all the wrong reasons – Super Flight Deck, which Airfix claimed complemented the enormous success of the original Flight Deck. Super Flight Deck differed from the original toy in that kids could not only attempt to land a jet on an aircraft carrier’s deck using the miniature power catapult included, they could also fire their Phantom fighter into the ether.

Air Traffic Control, with which budding Freddy Lakers could fly from London to New York, was another new game promoted on TV. Cutting between live action film of a Jumbo Jet taking off and a family playing this new board game, the commercial’s soundtrack featured recordings of real intercom exchanges between commercial pilots and air traffic controllers.

Airfix supported Air Traffic Control with some aggressive marketing, allowing purchasers of the game to enter a competition with prizes of a sixteen-day holiday in America for four lucky winners, each of whom would be taken on an escorted tour from New York to Toronto via Niagara Falls. Lucky winners would each receive a bonus £1,000 spending money, a fortune at a time when you could buy a house for £10,000.

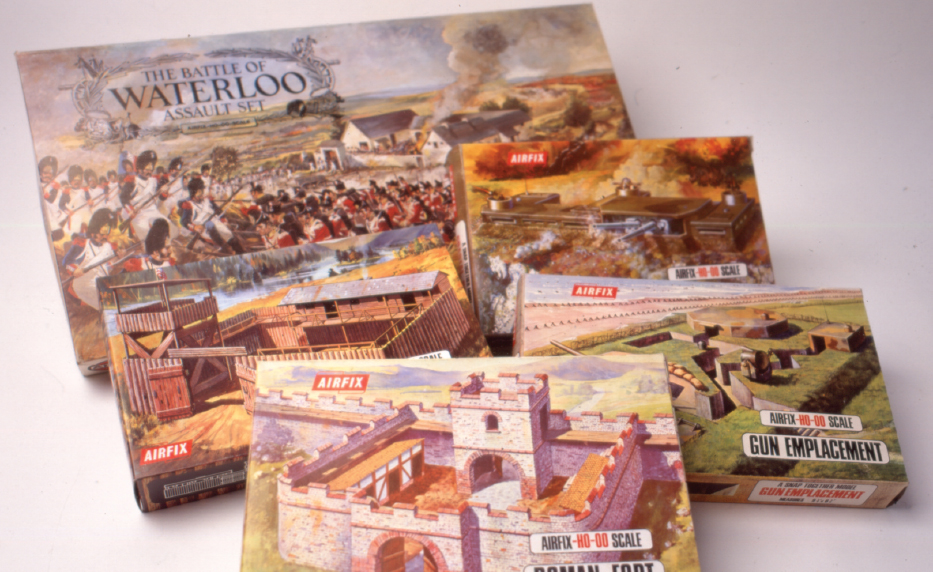

Following the success of Sergey Bondarchuk’s 1970 film Waterloo, interest in the Napoleonic wars had been on the increase. Airfix had done particularly well with a variety of 54mm Napoleonic kits in their new Collectors’ Series and the HO-OO and 1:32 scale polythene figures, snapped up in their thousands by youngsters and war games fans on a budget, also included British and French cavalry, infantry and artillery. There was even an impressively boxed Waterloo Assault Set, which came complete with a snap-together replica of an 1815 period French farm house and, as a bonus, only available in this compendium, a selection of accessories such as a couple of horses and carts, barrels, chests, sacks and bales – and even a spade and pitchfork to boot.

Now, on the 160th anniversary of the battle, Airfix added to their Napoleonic line with the introduction of the Waterloo Wargame. Promoted with the slogan ‘The Battle of Waterloo – could Napoleon have won?’ this new product was aimed to appeal to the general purchaser and the more serious war games fan. Featuring dozens of HO-OO scale blue and red figures, Waterloo Wargame also made economic use of Airfix’s existing moulding tools. In fact, in investment and production terms it was a very inexpensive product to produce.

Substantially more expensive than Waterloo Wargame, in terms of tooling investment and materials at least, was Fighter Command, a new game released by Airfix the following year. Backed by full-scale television advertising and extensive press publicity, Airfix said it was ‘confident this new game would appeal to children – and dads.’ A publicity photograph from the time showed a typical nuclear family – all, for some reason, wearing different brightly-coloured turtlenecks – cracking up with mirth as a Messerschmitt dived from out of the sun on a hapless Spitfire. Mum was in the background, also forcing a smile, but you could see the pathos behind her eyes. Mums know that war isn’t really a laughing matter.

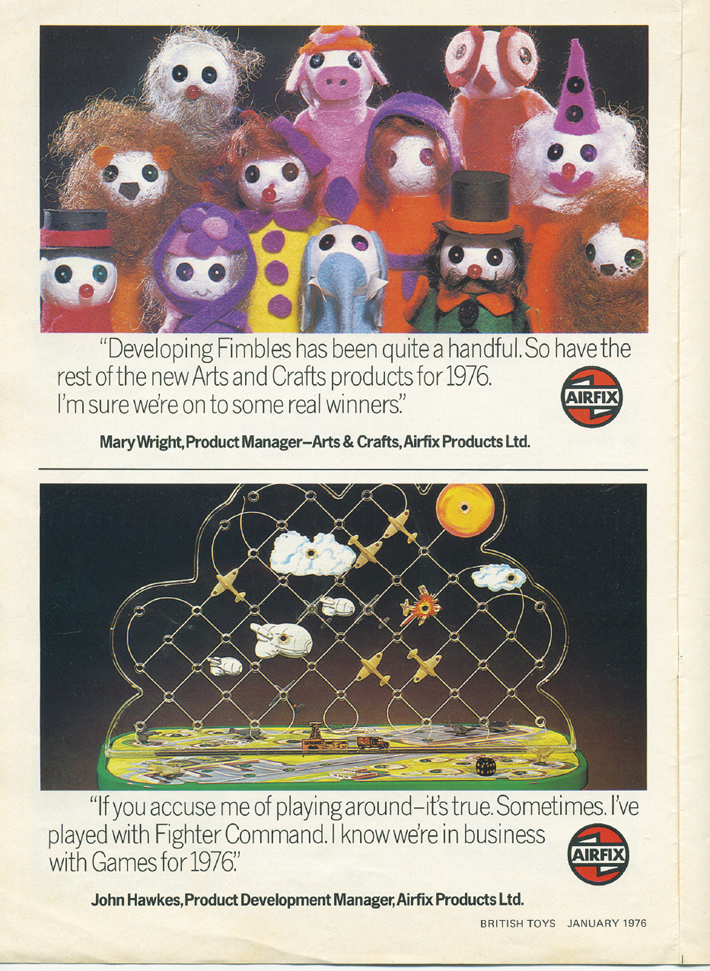

Fighter Command was one of the series of products featuring in a coordinated press campaign where senior Airfix executives put their money where their mouths were and endorsed the new products from their divisions.

A selection of HO-OO accessory sets, including a pretty rare Waterloo Assault Set from 1975. This was re-released to much acclaim in 2008.

‘If you accuse me of playing around – it’s true. Sometimes,’ said Airfix Product Development Manager John Hawkes in the first line of copy of the ad for the new game. ‘I’ve played with Fighter Command. I know we are in business with games for 1976.’

Nearing a fat old million, Airfix committed £900,000 to marketing in 1976. Chief Executive of the Toy Division John Gray earmarked nearly half of this, £400,000, for national TV advertising alone. Interestingly, for the first time ever, Airfix commissioned a cinema commercial specifically for children’s matinee time to be shown in 220 cinemas. Entitled Make History with Airfix, it has to be admitted that the film focused on the firm’s core plastic kit line, but it was a brilliant way of targeting the youth market and was expected to be seen by nearly one million children.

‘Knock your enemy from the skies,’ cried the blurb on the box of Airfix’s 1976 Fighter Command tabletop game. In fact, when you positioned your Spitfire playing piece over a space occupied by an enemy Me109 you literally did, pushing Willy Messerschmitts’s monoplane fighter from the vertical playing surface and watching it tumble, but not at scale speed, to the ground below. I wonder who was Hermann Goering – Mum or Dad? (From the V&A Museum of Childhood archive. Copyright Airfix)

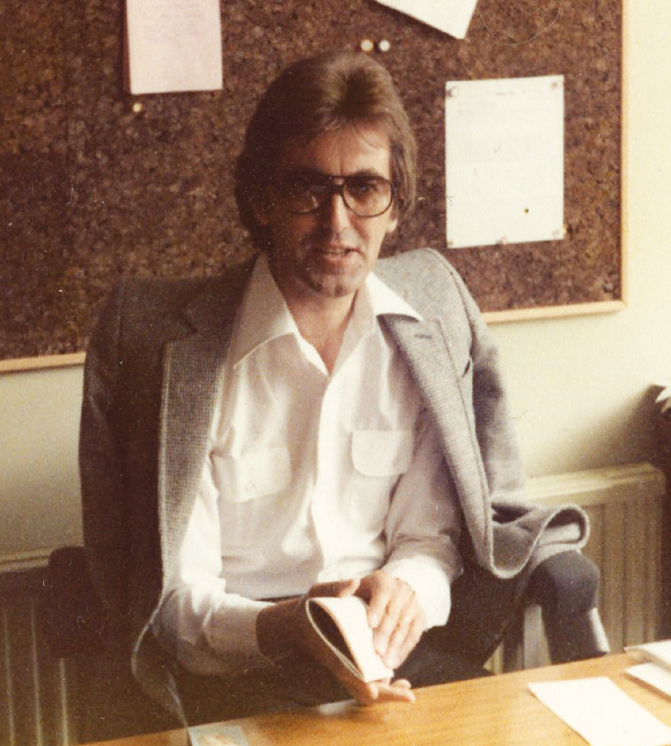

Airfix Product Development Manager John Hawkes.

Super Flight Deck continued to be heavily promoted and held its place as a main line toy in the Airfix range for the third year running. Weebles and Got-a-minute, a new dice game Airfix hoped would also appeal to the executive toy market, and various Arts & Crafts sets were also heavily promoted.

In fact, the continued efforts of Airfix Arts & Crafts Product Manager Mary Wright and her team were delivering what Airfix News called ‘a vintage year for Arts & Crafts’ in 1976.

‘Already the foremost UK supplier, particularly for the younger age groups, Airfix Products has not only introduced many new items and subjects, but also carried out a number of major revisions to existing series,’ the newsletter said.

Further developments in quick-drying paint technology made New Artist, or specifically, Fast Dry sets, more appealing to children and their parents alike, but the big news seemed to be about Fimbles, a range of twelve curious-looking finger puppets.

Airfix 1977 Arts & Crafts catalogue.

‘Reports (so far unconfirmed) are that half a million Fimbles may soon be invading the UK,’ Airfix pre-sales publicity forewarned. Sold in kit form together with a cartoon-style book with the script for a play, each member of the Fimble family featured in a new television commercial.

Mary’s name even appeared on a toy trade press ad for the Airfix newcomers:

Developing Fimbles has been quite a handful. So have the rest of the new Arts & Crafts products for 1976. I’m sure we’re onto some real winners. Mary Wright, Product Manager – Arts & Crafts, Airfix Products Ltd.

‘We have already sold twice the year’s budget figure,’ Mary Wright proudly reported at the time. Airfix would miss her greatly when, later in the year, she left prior to the birth of her first son. Fortunately, subordinates Sue Godfrey and Graham Westoll would step admirably into her shoes. But more about them later.

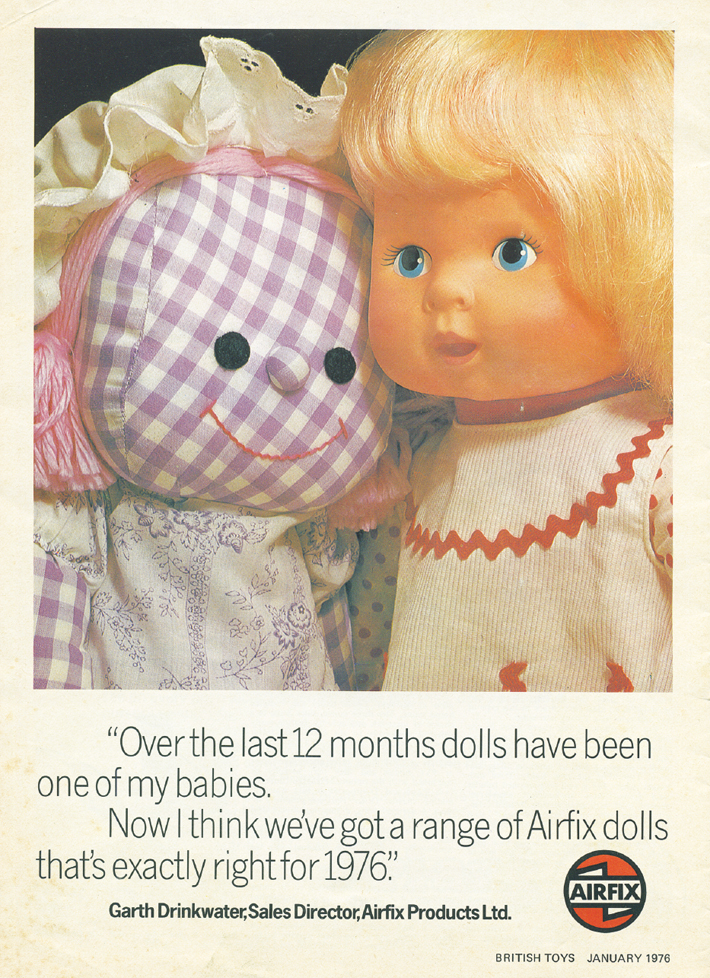

One of the most impressive ads released in 1976 was for Airfix dolls. A full page number in the campaign revealing the names of the movers and shakers behind the firm’s new products, this one featured the endorsement of Garth Drinkwater, Airfix Products’ sales director:

Over the last twelve months dolls have been one of my babies. Now I think we’ve got a range of Airfix dolls that’s exactly right for 1976.

Sales Director Garth Drinkwater got a name check in this full page advertisement for Airfix dolls in 1976.

Airfix Summer Time Girls comprised a range of plastic lovelies each kitted out in the latest 1970s’ fashions. By then, miniskirts were so … yesterday. As the packaging reveals, maxi skirts were now all the rage.

Perhaps the biggest news from Airfix in 1976 and much trumpeted at the Brighton Toy Fair that year was the company’s entry into the model railway business.

Airfix allegedly purchased the Kitmaster model railway range nearly fifteen years previously, mainly to eliminate a competitor. Since then, whilst there had been no domestic challenge in the area of static construction kits of HOOO trains, rolling stock and accessories, in the electric railway field Airfix didn’t even make a blip on the radar. Since 1962 it had become a major player in the British toy and games industry but still had nothing to rival the products of British competitors Tri-ang Hornby, then owned by Dunbee-Combex-Marx, or European brands such as Rivarossi, Lima, Märklin or Fleischmann.

‘The company’s decision to enter this market is a mixture of many important factors, which, it is felt, will help the market’s growth,’ said John Gray. ‘The more companies there are in a market, the bigger the market gets,’ he added. ‘This is therefore a responsible decision by Airfix to create sales and build up a market share.’

Gray was equally matter of fact in a letter he sent out to dealers just after the January toy fairs at Brighton and Harrogate in 1976.

‘Airfix will enter the model railway market in 1976 and we intend to take a major share,’ the letter opened. He continued with details of Airfix’s commitment to both modern and steam locos and by stressing that the couplings used would be universal, thereby enabling customers to integrate the new system with their existing models. He then added, ‘The track system is made to Airfix specifications – supplied by PECO – and the rail will be moulded into the sleepers,’ and went on to stress that Airfix would back everything with the ‘biggest TV launch campaign ever on model railways.’

A trio of Airfix Eagles Adventure Sets.

Confident of the success of his new product, Gray urged customers to place orders and ‘make sure you save shelf space for Airfix railways in 1976.’

In fact, John Gray was so proud of the new railway line that he even put his name on a colour press ad. Beneath a photograph of two of the new locos Gray was quoted thus:

I’ve been playing a lot with my train sets just lately. And when we launch our adventure sets in 1976, electric trains will never quite be the same again. John Gray, Managing Director – Airfix Products Ltd.

Unfortunately, Palitoy – then a rival of Airfix – had a similar idea and decided to enter the British model railway market, launching their own product, Mainline, at the same time. Despite Airfix’s best intentions, purists tended to prefer Palitoy’s offering, which featured better detail, so much in fact that even market leaders Hornby had to go back to the drawing board. Within five years, of course, Airfix would be part of Palitoy and the Airfix Railway System, by then renamed GMR (Great Model Railways), and subsumed into the Mainline family.

But when the new Airfix train sets arrived they lived up to the hyperbole.

Traditionalists could purchase the Great Western Suburban Train Set or the BR Steam Goods Set, with their coal-fired locos, pistons and boilers. Aficionados of post-Beeching axe trains might opt for the Inter-City Train Set or the BR Diesel Mixed Freight Train Set. More adventurous customers might prefer the Wild West Adventure Train Set, or the Dr ‘X’ Adventure Train Set.

Appealing to children who wanted their HO-OO trains to more than, well, just go round and round an oval layout, the Wild West Set and Dr ‘X’ Set were quite a change from regular model railway toys.

In the brand new first edition catalogue for the Airfix Railway System new train sets were illustrated in great detail. Train sets, locos, carriages and rolling stock were photographed close up and their full specifications were listed.

A strip cartoon accompanied both of the new adventure sets.

The Jupiter 4-4-0 loco with bright red plough-shaped cowcatcher protruding from the front could be seen passing under a gantry from which a bandit was hanging. As soon as the passenger car passed beneath, a lever was tripped, a trapdoor opened and the cowboy dropped within. This wasn’t all that happened. Oh no. If the steam train backed up the last coach was automatically uncoupled and a hidden bandit clutching a stick of dynamite would appear from behind a rocky outcrop next to a log cabin. The touch of a detonator button would result in the baggage car door being blown open. More bandits would then appear from the log cabin, removing the baggage car’s safe in an attempt to steal the gold it contained. ‘Will they get away?’ asked a caption beneath the final frame of the cartoon strip.

Costing just 10p, the first edition Airfix Railway System catalogue from 1976.

The Dr ‘X’ Set was no less dramatically described. This time, instead of triggering trapdoors and blowing up a train, the ingenious mechanisms built into the … wait for it … BR Class 31/4 A1A-A1A Diesel Loco unleashed hell. Missiles were fired, a breakdown truck stalled on a level-crossing, Dr ‘X’s radar scanner popped up and Dr ‘X’s secret laboratory was revealed. ‘Dr ‘X’ holds the world to ransom! Will he succeed?’ was how this story ended.

In his excellent book Airfix’s Little Soldiers, author Jean-Christophe Carbonel enthused about the figures in the Dr ‘X’ Set – especially the villain of the box:

The Dr ‘X’ is very much sought after by collectors because the figurine of Dr ‘X’ himself seems to be a caricature of Gert Fröbe in the role of ‘Goldfinger’ with a little bit of Hergé’s Rastapopoulos.

Toys like the new Airfix train sets were heady stuff and a real treat for teenage kids in the 1970s. They may seem a little quaint now but in those days youngsters didn’t have videos and video games, and the only PC was the one who shouted at you if your rode your bicycle on the pavement.

Equally heady stuff was the fact that, for an amazing fifth year running, Airfix Products was awarded the Top Toy Trophy by the trade magazine Toys International.

One final observation I can’t help making about Airfix in 1976 concerns the announcement regarding the introduction of its new computer system. ‘One of the biggest mini-computers in Britain – a 392K Digital Equipment Company PDP 11/70 – has just been installed at our Wandsworth Computer Centre,’ trumpeted the Airfix PR blurb, continuing, ‘The whole unit measures only [“only”!] 12ft long by 3ft wide and 6ft high, a fraction of the size of the existing equipment, and is a number of times more powerful.’

Don’t laugh – the Apple 1, released the same year, possessed a memory of only 8Kb.

The triumvirate of John Gray (who had overall responsibility for Airfix Products, Meccano, Tri-ang Pedigree and Plasty), David Sinigaglia (a relative newcomer compared to Gray, having joined Airfix in 1963 and now in charge of Airfix Plastics, Airfix Footwear, Crayonne, Declon and Airfix Packaging Developments) and, at its centre, Ralph Ehrmann, chairman and managing director of Airfix Industries Limited had a lot to be proud of.

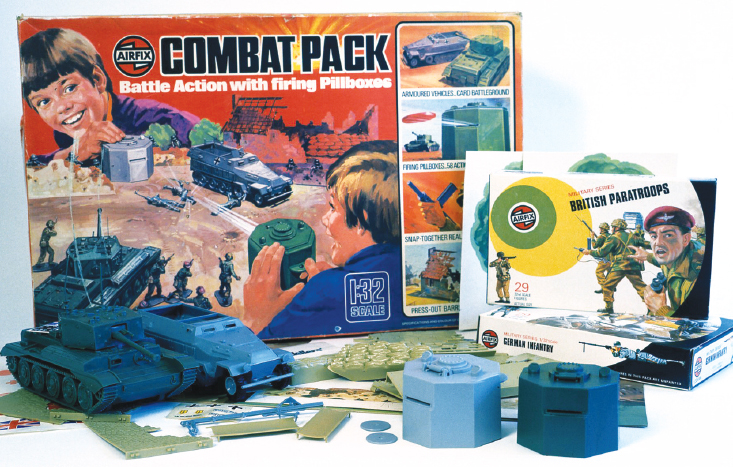

Combat Pack, probably the most sought after Airfix toy from the 1970s. In fact, there were two different types available when they were released in 1979, first appearing in the thirteenth edition of Airfix’s perennially popular catalogue. The one shown here is the standard Combat Pack featuring British paras and German infantry, each respectively supported by a Matilda tank and a Hanomag half-track. There was also a Desert Combat Pack, which came in a stout box full of 8th Army and Afrika Korps soldiers, a Daimler armoured car and a Panzer IV. The European ruin had been replaced by a suitably North African dwelling. Both sets contained miniature pillboxes, which each fired missiles that were easily capable of demolishing row upon row of advancing troops. Great fun! (From the V&A Museum of Childhood archive. Copyright Airfix)

By 1977, the efforts of Airfix’s management and staff were delivering a stunning performance. Within the space of ten years, the company’s turnover had increased eightfold, from £5 million in 1967 to £40 million. Profits had grown with equal vigour and, before tax, in 1977 they stood at more than £4 million (profits had been £550,000 in 1967). It was the eleventh consecutive year of expansion for Airfix.

‘The basic stability of the group is in the ongoing products that strengthen our position in the marketplace from year to year,’ said Ralph Ehrmann at the time.

Airfix continued to expand overseas. In fact, export sales were becoming increasingly important to the company, accounting for forty per cent of the total sales of toys and household accessories.

To facilitate its international business, both in terms of local manufacture and distribution, toy and kit production facilities at Waco in Texas had been secured, Airfix taking a forty per cent stake in the US company Ava International, which had production facilities in a town that would be become better known for all the wrong reasons in 1993.

Promotional material from the time featured comely female Texans wearing Stetsons and sporting T-shirts bearing the neat USAirfix logo as they laughingly packed 1:32 plastic soldiers into their then new ‘target’ boxes.

Crayonne had similarly gone west, purchasing the assets of Sheina Industries in New Jersey in December 1976. Sheina’s premises were to be used for manufacturing and sales, with space for offices and showrooms.

Airfix’s ownership of traditional lines was also yielding financial rewards. The Dinky Division of Meccano captured a record £300,000 order from the US in 1977, and even the annual exports of veteran toy brand Tri-ang Pedigree had jumped to a record high of £500,000.

Airfix News recorded that the company’s salesmen were clocking up thousands of air miles. George Flynn, Meccano’s managing director, had just returned from Moscow, a sales team was just back from the Middle East and myriad other executives from every corner of the US.

‘But the VIP prize for jet-setting goes to Toy Division Chief Executive John Gray,’ said an article entitled ‘Overseas business surging ahead’. ‘He has clocked up thousands of miles over the past twelve months. John doesn’t miss an opportunity either. On a trip to the US by Concorde he handed out Concorde kits to each of the ninety passengers onboard.’

‘The international status of the Airfix Group is now firmly established,’ the article concluded. ‘As the slogan for this year’s corporate advertising says: Airfix Nation-Wide, World-Wide.’

Perhaps the biggest new toy lines at this time were Micronauts and Airfix Eagles.

‘Even H.G. Wells would have been hard put to dream up the latest introduction from Airfix – the Micronauts, a mind-boggling range of futuristic figures and vehicles,’ trumpeted Airfix PR in the late 1970s.

In fact, Micronauts weren’t actually introduced by Airfix; they were originated by Japanese company Takara, starting life in the Far East in 1974 as Microman. Microman toys were imported to the United States by the Mego Corporation in 1976 and their name was changed.

Beginning life in 1971, Mego started out by purchasing the licensing rights to TV, film and comic book properties like Star Trek and Planet of the Apes. They were also behind Action Jackson, the ill-conceived competitor to Hasbro’s GI Joe. But with Micronauts, Mego struck gold. The range was an enormous success in the US and many more figures and vehicles were available there than were released in the UK by Airfix and, stateside, Micronauts were supported by massive TV advertising campaigns.

Airfix Eagles, the company’s successful attempt at grabbing the burgeoning 3-inch figure market, which burst to life with the advent of Star Wars figures in 1977.

Before it did the deal for the UK and European rights to Micronauts, Airfix already had a relationship with Mego, having released a doll of Charlie’s Angels’ star Farrah Fawcett wearing a white jumpsuit, complete with shoes and stand.

Airfix Micronauts were pretty much the same as Mego’s versions, the only real difference being Mego’s branding being replaced by that of Wandsworth’s finest.

Although there were only nine separate items launched initially, the secret to Micronauts was the interchangeable nature of all the parts, meaning purchasers could transform their basic Time Traveller figure, for example, into a two-headed Microtron simply by pulling off limbs and exchanging them with other body parts. A variety of vehicles were provided to accompany the figures, and everything was interchangeable. Some toys, simple figures like the Time Traveller, were packaged in simple blister packs. Others like the vehicles or complex, multi-faceted figures such as Baron Karza were very smartly presented in larger boxes with all the pieces neatly held in place in snug-fitting expanded polystyrene.

The mighty Microtron, one of the Airfix Micronauts range.

Micronaut Baron Karza, ‘With Mago-Power Action and Firing Fists and Missiles’. Not someone you would want to get into an argument with then …

Airfix Flying Bird. Imagine the disappointment on parents’ faces when their eager and excited youngster opened this box on Christmas morning, the contents of which revealed an item that looked like a printed swing-bin liner attached to a coat hanger. Despite first impressions, however, the contraption actually worked, delivering hours of healthy outdoor fun.

Standing at a little over 4ins tall, Airfix Eagles action figures were fully jointed at the ankles, knees, hips, waist, shoulders, wrists and neck. They actually began life in Mannheim, south-western Germany, originated by Airfix subsidiary Plasty-Spielzeug, where they were marketed as Action Stars. Ironically, Airfix sold them under the more Germanic banner, Eagles.

Airfix decided to support their new toy with TV advertising and soon the seven new figures consisting of Captain Eagle, a deep sea diver, scuba diver, paratrooper, field medic, military policeman and commando were in the thick of it at teatime. The theme of the campaign was simple: ‘Small enough to fit in your pocket … big enough to save the world!’

John Gray was very enthusiastic about the launch of a home-grown (well, if not exactly home-grown, at least from Europe) toy line rather than another one imported from the US.

‘This is an excellent example of international as well as inter-company collaboration,’ he said. ‘Our German associates identified a market and saw they had a good item with these figures. We spent just three days looking at them in London and decided likewise. There are, of course, differences in the two markets and while Plasty have gone for real life situations we have decided on more fantasy in our characters.’

Very soon Airfix would go to town as far as fantasy was concerned, supporting individual figures with an extensive range of accessory sets. These included: Treasure of Atlantis Adventure Set; Jaws of the Jungle Adventure Set; Earthquake Adventure Set; Terror of the Deep Adventure Set; Mystery of the Pharaohs Adventure Set; and the Mission Impossible Adventure Set.

Plasty even produced a natty hang-glider to accompany their Action Stars range, but I don’t think this was available in the UK under the Eagle brand. The Germans were equally enthusiastic, more, I guess, because it was their idea after all, Plasty’s managing director, Peter Bentz, even saying, ‘Our product philosophy and our marketing and advertising strategy for Action Stars are right on the mark.’ I wonder if he intended the pun.

So confident of their achievements, and rightly so, in my opinion, Airfix were really beginning to shake up the UK toy industry.

Dinky Toys had always been a big and expensive die-cast toy, a birthday or Christmas treat rather than a pocket money purchase. Ogle Design, who had worked on the Meccano Mogul, created a range of budget-price Dinky Toy commercial vehicles to keep the production line at Liverpool busy.

Known as the Convoy Range, the five models included a skip wagon with removable skip, an army truck with removable moulded canopy, and a farm wagon with opening tailgate. There was also a fire vehicle and dumper truck with similar moving features.

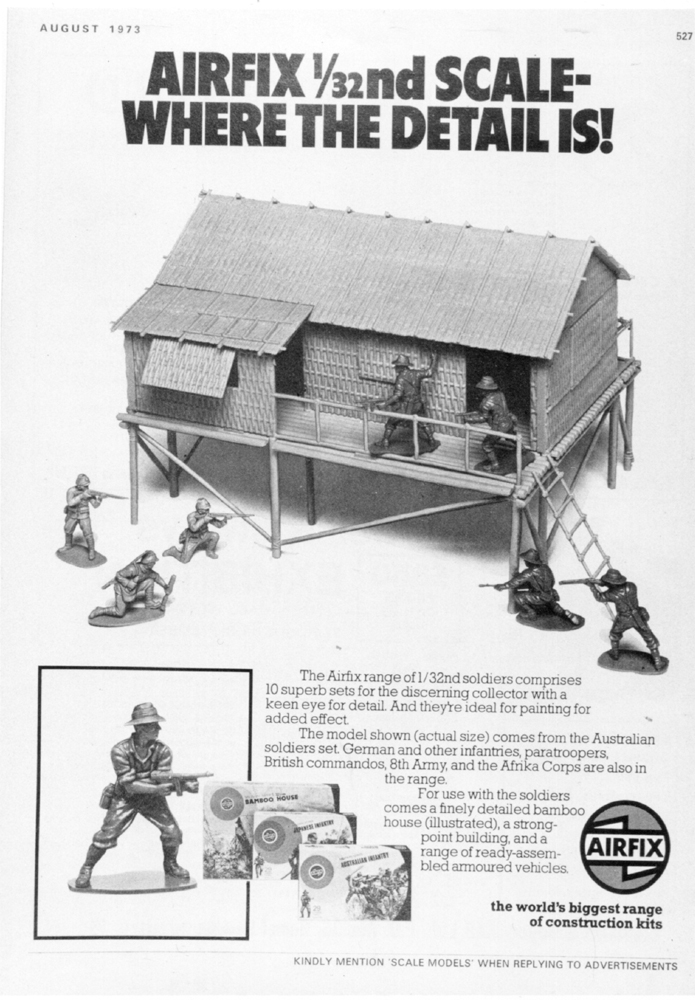

August 1973 press ad announcing the arrival of the 1:32 Bamboo House to complement the firm’s similarly scaled Australian and Japanese soldiers.

As if reducing the size and price point of Dinky Toys wasn’t enough, Airfix went one further and produced an almost unthinkable variant of a Binns Road classic – Plastic Meccano! Marketed under the banner ‘A New Generation of Meccano’, the new Plastic Meccano had been enthusiastically received by both home and overseas markets following its revelation at the 1977 toy fair.

The new sets were completely compatible with the traditional steel Meccano pieces but, said Airfix, offered greater realism and more versatility. ‘Plastic Meccano can, of course, be used in conjunction with the metal version,’ said an Airfix spokesman, ‘and encourages youngsters to move on to the more sophisticated product.’

There was a lot of PR for Weebles at this time too after the wobbly but stable toy appeared on the BBC TV series Are You Being Served. To everyone’s surprise at Airfix, Weebles had been written into a scene that saw cast members visiting Hamleys, the famous London toy shop.

Airfix Marketing Manager Ernest Boltitude was quick to capitalize on the promotional opportunities such TV exposure presented, however. Quick as a flash he enlisted the services of the show’s star, ‘cheeky’ John Inman, for some in-store appearances. Airfix PR showed a photo of smiling Mr Inman in the toy department of a Kingston (Surrey) store surrounded by a large crowd of happy kids each thrusting pens and Weeble products at him in the hope of getting his signature. The caption to the press photo read: ‘John Inman, pictured here at a promotion in Kingston, obliged by serving up plenty of fun to the youngsters with his Wibbly Wobblies, as he calls them.’

Not strictly toys perhaps, but the late Roger Hargreaves’ then quite new Mr Men characters had found their way into the Airfix story. Hargreaves was working as the creative director at a London ad agency when he conceived Mr Men in 1971, but it wasn’t until 1974 that his first book, Mr Tickle, was published. Such was the success of his idea that by 1975 actor Arthur Lowe was narrating a BBC TV series about the various characters.

By the late 1970s, Airfix subsidiary Declon Foam Plastics Ltd had secured a massive order supplying Mr Men foam sponges to British retailer Boots. ‘The launch, exclusive to Boots, is aimed at boosting sponge sales by adding extra interest and novelty to the product,’ said Airfix PR. ‘For Declon this could also be the start of something big in international terms. The possibility exists for marketing the sponges in a number of countries overseas within the worldwide licensing arrangements currently being negotiated for the whole range of Mr Men products. A TV series is due to start in the US, which will make America the number one overseas market. Not unreasonably, Declon’s boss, Glynn Hart, had high hopes for the future. His division was already the biggest supplier of sponges in the Republic of Ireland and under his stewardship the division’s hi-fi speaker fronts were making major inroads into Europe and the US.

As the 1970s drew to a close Airfix was everywhere, almost literally. Not only was it a world famous plastic construction kit brand, it also produced a range of toys, games, arts and crafts. Although it imported most of these products, many of them were manufactured at its principal premises at Haldane Place in Wandsworth. Today, many of the buildings survive but instead of belonging to one company, the various units are leased out to individual businesses.

Airfix also used an old London County Council trolleybus repair depot in Charlton, South East London, as a factory for model railways, amongst other items. This has now disappeared as part of the redevelopment of the Greenwich Peninsula.

From their desks in the Airfix Industries head office in Kensington, Chairman and Chief Executive Ralph Ehrmann and Managing Director David Sinigaglia surveyed an impressive empire. By August 1979, it had been streamlined by uniting the two manufacturing divisions Airfix Products and Airfix Plastics under one overall boss, Sinigaglia. John Gray had become the new products director.

‘Last June the two divisions were combined and I became managing director of them both,’ said David Sinigaglia in Airfix News that summer. ‘I have been directly involved in the Industrial Division since 1962. In 1973, I formed our highly successful subsidiary Crayonne, and a year later became managing director of the Industrial Division of Airfix Industries. Recently, international markets have changed, and having two separate divisions has ceased to be an advantage. We now need unified management to make the best use of our resources and of opportunities throughout the world.’

Together with the industrial plant at Wandsworth and Chartlon, Airfix also managed Crayonne’s factory at Sunbury, Airfix Footwear at Harworth, Meccano in Liverpool, MRRC slot cars in Bournemouth and Declon in Dunstable. Also in the UK was South Wales Plastics at Aberdare and Airfix Packaging, masters of the APD composite packaging process, which enabled full-colour Flexographic printing onto plastic mouldings for items like dairy and confectionery products.

Airfix even numbered a design company amongst its assets. Covent Garden-based Benchmark opened its doors, rather inauspiciously, as it turned out, on 1 April 1979. Working for companies within the Airfix family and for new clients outside, Benchmark was managed by David White, previously creative director in charge of Product and Graphic Design with Conran Associates. Benchmark certainly began life with the highest credentials.

Overseas, Airfix had its new Crayonne facility in New York and USAirfix in Texas. There were further Crayonne premises in Frankfurt and Milan. The ‘Italian end’ of TAL Impex was based in Florence, and Plasty was located at Neulussheim, in Germany.

Actually, there was another Airfix subsidiary at Charlton. TAL Impex, who supplied Italian-designed and manufactured footwear and accessories, shared the premises with Airfix model train sets.

By 1979, even Airfix trains sets had changed. The Airfix Railway System had become Great Model Railways. Its logo, GMR, picked out in yellow within a red/brown oval, was reminiscent of the classic badges of famous operators like the Great Western Railway (GWR) or the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS). The traditionally executed branding was in keeping with Airfix’s mission statement: ‘Airfix train sets were re-launched at the Earls Court Toy Fair under the initials GMR – Great Model Railways, with the selling line “Precision made by Airfix”,’ said the catalogue. ‘They have been designed for those who wish to recapture the history of railways in the authentic detail that Airfix has become famous for.’

When Airfix first entered the model railway market they sourced much of the design from overseas, mainly Hong Kong, where Bachmann (a US company founded in 1833) worked closely with Mr Ting Hsiung-Chao’s plastics company Kader. Purists might recall Kader kits from the early 1960s – I have a couple in my collection. From 1969, Bachmann and Kader worked together expressly on model railway projects. Airfix, of course, had worked closely with Bachmann since the early 1970s, principally on the tiny, and now very collectable, Airfix/Bachmann Mini Planes toys.

Bachmann and Kader were heavily involved with models, such as the Wild West Adventure Set. Communications between London and Hong Kong were never perfect and gradually Airfix turned to designing and manufacturing its own trains and rolling stock at Charlton, which was somewhat closer to Wandsworth!

Airfix brought Mike Whightman into their development team specifically to work on the Model Railway Development Project. He was a superb model engineer and was responsible for creating the prototypes for the locomotives in the range, including one of his best, a superb GWR 4-6-0 Castle Class, as well as carriages and freight wagons. His skills extended beyond the modelling of the locos and rolling stock and he was a major contributor to making sure that the locos had the best, most efficient motors in the market.

As well as his involvement in trains he was a key contributor to the development of the Airfix Hovercraft, about which we will hear more later.

I was told that, although Mike was born in England, when he was about four his family moved to America. All through his schooling, when each day the class swore the oath of loyalty to the flag, he used to pull out a little Union flag from his pocket to swear his oath to the Queen. A dual nationality boy but a Brit to the core – and proud of it!