Baekeland, Antony, 1946-81, Brit. Barbara Baekeland’s relationship with her son Antony bordered on obsession. On Nov. 17, 1972, Tony murdered his adoring mother at their lavish London penthouse.

Antony Baekeland, great grandson of the “father of modern plastics” and heir to the family fortune, was a troubled youth with homosexual tendencies. When he was twenty-one his parents separated. While living with his mother, Tony began experimenting with LSD. After he stabbed Barbara in the London penthouse, he placed an order for Chinese food just as the Chelsea detectives arrived. His trial began at the Old Bailey on June 6, 1973, and it was a sensational one, highlighted by rumors of incest between Barbara and her son. Witnesses told how the former movie star desired to “cure” her son of his homosexuality. Tony Baekeland, was convicted of manslaughter under the “diminished responsibility” statute in British law. He was sent to Broadmoor, where he remained for the next seven years. In July 1980, Tony was discharged from custody and flown to New York to live with his grandmother Nina Fraser Daly. A week later, Baekeland assaulted the elderly woman with a knife because she refused to “quit nagging him.” Mrs. Daly survived the attack, but criminal charges were filed, and once again the young heir found himself behind bars, this time on Riker’s Island. It was there that Tony Baekeland ended his life, on Mar. 21, 1981.

Bagg, Arthur Richard, 1914- , S. Afri. On Nov. 23, 1937, Arthur Richard Bagg, a 23-year-old South African, savagely stabbed his 17-year-old lover in a fit of jealousy and rage and later dumped her mutilated body under a viaduct on Oaklands Atholl Road outside Johannesburg. He was taken in for questioning several days after the partially-clothed body of Marjorie Patricia Rosebrook was found stabbed twice in the breast with a small knife.

Bagg became a prime suspect three days later when, during questioning, his accounts of his activities on the day of Rosebrook’s murder did not correspond to those given by witnesses who had seen the two lovers together that day. After several attempts by Sub-Inspector U.R. Boberg to compel him to tell the truth, Bagg finally broke down and confessed to the murder. He later re-enacted the events of that day, taking detectives to the site of the crime and explaining his actions in detail.

Although Bagg had confessed, police were unable to locate the murder weapon and several articles of clothing missing from the dead girl’s body. They repeatedly scoured the sites where Bagg claimed he disposed of them, but turned up nothing. After threatening to search his house, Bagg agreed to lead police to the missing items.

Bagg, described as somewhat eccentric, was an artist interested in mysticism and the occult. Unknown to anyone was his special affinity for the legendary vampire, Count Dracula. Bagg worshipped him and frequently conducted ritualistic services in his honor. He led police to the site of these rituals–a secret earthen chamber located below the floor of his bedroom. A trapdoor hidden underneath the linoleum provided access to the chamber, where police discovered the murder weapon and the missing bloodstained clothing. In addition, they found a piece of leather with writing carved into it: “I hereby befile (sic) the living God and serve only the Dark One, Dracula; to serve him faithfully so I may become one of his faithful servants.” It was signed by Bagg.

Bagg’s trial began on Feb. 28, 1938. During his testimony, he changed his confession and claimed the girl had committed suicide and that he was covering up for her with his earlier confession. The jury failed to believe him, and, after slightly less than two hours of deliberation, they returned a verdict of Guilty. Justice Saul Solomon sentenced Bagg to death, the maximum punishment for his crime, but this was later reduced to life imprisonment based on psychiatric evaluations of his mental state. Bagg was released in 1947 after serving only nine years of his sentence.

Bailey, George Arthur, d.1921, Brit. The January 1921 murder trial of George Arthur Bailey was the first murder trial in England in which women served on a jury. After the four-day trial was over, the three women jurors helped convict Bailey for the poisoning murder of his wife. He was sentenced to death and executed on Mar. 2, 1921.

Bailey, Raymond (AKA: Ray Carter), d.1958, Aus. Raymond Bailey was driving a DeSoto sedan with his wife on the Alice Springs-Port Augusta Highway in South Australia on Dec. 6, 1957. In the middle of the night, Bailey left his caravan, carrying with him a Huntsman single-shot rifle. He used it on Thyra Bowman, her 15-year-old daughter Wendy, and their friend Tom Whelan, who had set up camp for the night in the wilderness.

The Bowmans were on their way to Adelaide when they were overtaken by Bailey. Their bodies were located by an aerial search party looking for their missing automobile. Near their campfire several .22-caliber shell casings were found which matched the rifle found in Bailey’s possession. In Kulgera, several eyewitnesses reported seeing a DeSoto sedan. The car was spotted on Jan. 21, 1958, by Constable Glen Hallahan at Mount Isa in Queensland.

When questioned by police, Bailey said his name was Carter. He could not, however, explain a concealed .32-caliber handgun sewn under the front seat of his car. The suspect finally confessed to the shootings, but changed his story four times. Bailey was extradited to Adelaide and tried for murder. Deliberations opened on May 12, 1958, Sir Geoffrey Reed presiding. Less than eight days later the jury returned a verdict of Guilty. The death sentence was imposed within minutes, and Bailey was executed at the Adelaide Jail on June 24.

Ball, Edward, 1917- , Ire. Though the body of 55-year-old Vera Ball was never found, her son Edward was tried and convicted of her murder. Mrs. Ball was the wife of a Dublin physician. Following their separation, she lived with her 19-year-old son in Boosterstown, a suburb of Dublin. On the morning of Feb. 18, 1936, a newspaper delivery man stopped to investigate an automobile parked on an odd angle in Shankill, County Dublin. He found traces of blood on the front seat.

Identifying the car as belonging to Mrs. Ball, police went to the Boosterstown home. Here they were greeted by Edward Ball, who said he had last seen his mother the previous evening. Police searched the house, turning up several items of bloody clothing and discovering a large stain on his mother’s bedroom rug, none of which Ball could explain. When pressed further, he said his mother had suffered a recent bout of depression and had killed herself with a straight razor. Ball said he found her dead in her room, took the body to Shankill, and threw it into the sea.

His explanation did not convince the police, however, and Ball was charged with murdering his mother. Police believed he used a hatchet found in the garden, covered with blood. He was convicted of murder, but the jury also declared him insane. The judge ordered Ball detained at the discretion of the local governor-general.

Ball, Eli, prom. 1919, U.S. On Feb. 19, 1919, Ball murdered his sister Lilly Billings, and her husband Abe Billings, as they tried to remove furniture from the rural Kentucky home that had been willed to him by his sister, Nell Washam, when she died the previous year. Lilly Billings maintained that she was entitled to some of the farm’s furnishings, as it had all been inherited from the family by Nell when her parents died. Ball served several years in a state penitentiary for the murders, but was released to return to the homestead in Bear River Valley, Ky.

Ball, George (AKA: George Sumner), 1892-1914, Brit. The 22-year-old Ball worked as a clerk in the shop of John Bradfield in Liverpool. He was assisted by a dim-witted 18-year-old, Samuel Angeles Eltoft. The shop’s manager was 40-year-old Christine Catherine Bradfield, a hard taskmaster who was known to neighbors as a kindly person. She tolerated no nonsense in the shop which sold tarpaulins manufactured by John, her brother, and she was forever prodding Ball, who was known as George Sumner by his employers. On the night of Dec. 10, 1913, Walter Musker Eaves, a ship’s steward who was waiting for his girlfriend in Old Hall Street and who was standing directly in front of Bradfield’s, suddenly had his new hat knocked off his head when one of the shop’s shutters blew off. The shop appeared dark but within a few minutes Eltoft appeared and picked up the shutter. Eaves showed him his hat and demanded that he be paid for the damage done to his bowler by the shutter. Eltoft politely asked him to wait and soon emerged with Ball who courteously paid Eaves two shillings for the creases made in the hat.

Eaves was still in Old Hall Street when, a short time later, both Ball and Eltoft appeared, pushing a tarpaulin-covered cart with considerable effort up the street, and disappearing around the corner. The next day Eaves read a newspaper report about a woman’s body being found in the Leeds-Liverpool canal by a bargeman who had fished the body, sewn into a sack, out of the canal. The steward went to the police who had just escorted John Bradfield from the morgue. Bradfield had also responded to the newspaper report when his sister had failed to return home from the shop and he had identified the body, telling officers that he had no idea who would want to murder his sister.

Detective Inspector Duckworth of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), after interviewing neighbors and shop customers, realized that the only real suspects in the case were the two clerks, Ball and Eltoft. He decided to interview Eltoft first, realizing, when John Bradfield talked about the pair, that the younger clerk was impressionable and gullible. He waited until late on the night of Dec. 11, 1913, then forced his way into Eltoft’s room, startling the youth and grilling him so intensely that Eltoft blurted out the fact that his superior, George Ball, had bludgeoned Christine Bradfield to death. Ball hated her constant nagging and, after she ordered him to do something, he had suddenly exploded and crushed the woman’s head with an iron pipe, forcing Eltoft to help him dispose of the body. Duckworth, placing Eltoft under arrest, then raced to Bell’s boarding house but the young man had fled. His landlady later stated that Ball had returned home the night before and she had noticed bloody scratches on his face. He told her that he had received the injuries at the shop where he worked, adding: “It’s a rotten business.”

The scratches, coupled with some of Eltoft’s confusing statements later given in court, suggested that Ball had raped the spinster in a back room of the shop and she had scratched his face; in retaliation he had struck her on the head with the pipe.

The Liverpool police, despite a desperate search for Ball, were unable to locate him. Duckworth was struck with an inspiration. He was a movie fan who believed that the movie theaters springing up all over Liverpool could be of great service to the police in tracking down Ball. He had the fugitive’s photograph shown on all the screens of the theaters between features, running beneath the photo a title card which read: “GEORGE BALL, WANTED FOR MURDER, REWARD.” This was the first time that movies had been used in tracking down a wanted criminal, and the technique proved effective. Ball, who had moved and disguised himself, was identified by someone who had seen his photo in one of the theaters as he left a football match on Dec. 20, 1913. He was immediately arrested and tried in February 1914 at the Liverpool Assizes, Justice Atkin presiding. He was defended by Sir Alfred Tobin, who had been the lawyer for the notorious wife-killer, Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen. Prosecuting the case was Sir Gordon Hewart.

The trial was one-sided with Hewart utterly destroying the testimony of the nervous Ball who rattled off a fantastic story about “a tall chap with a dark brown mustache” who sprang from behind a pile of tarpaulins in the shop just before closing and attacked Christine Bradfield, killing her, then held a revolver on Ball and Eltoft, telling them that if they did not dispose of the body for him, he would kill them both. Hewart shredded this tale quickly, asking Ball why, when he went to the street to pay Eaves for the destruction of his hat, he did not ask the burly steward for help since, according to Ball’s own testimony, the killer was still in the shop at the time. Ball could only mutter: “I was afraid.” Moreover, Hewart pointed out that the victim had been carefully sewn into a tarpaulin sack with a system of stitching that was peculiar to the method used by Ball.

The jury returned a Guilty verdict, and Ball, as he was being dragged away by four warders, cried out: “I am innocent! Innocent!” He was sentenced to death and his dull-minded accomplice Eltoft was given a four-year prison sentence. When realizing that there would be no appeals or commutations, Ball confessed the murder of Christine Bradfield to the Bishop of Liverpool only hours before he was hanged at Walton Prison on Feb. 26, 1914. See: Crippen, Dr. Hawley Harvey.

Ball, Joseph (Joe), 1894-1938, U.S. Joseph Ball was a serial killer who murdered perhaps as many as twenty-five women. All of his victims were young and beautiful. Though Ball took their possessions and whatever money they had when he murdered his victims, his motive was love. He killed one woman after another, including his second and third wives, so that he would be able to devote his time to his next paramour. To Joe Ball, these murders were not without a utilitarian end; he chopped up his victims and fed them piecemeal to the five pet alligators he kept in a foul-smelling pool behind his inappropriately named gin mill, The Sociable Inn, located near Elmendorf, Texas. This Lone Star native was educated at the University of Texas but he found legitimate pursuits uninteresting and, at the dawn of Prohibition in 1920, he became a bootlegger, amassing a considerable fortune.

The young bootlegger worked hard at his illegal profession which confused his friends who knew that his wealthy family had offered Ball any number of lucrative positions in its vast holdings in cattle and commerce. He had turned all this down to go his own way. He bought a house in Elmendorf and operated out of here during the 1920s, selling flavored alcohol at $5 a gallon. Though the house was modern, Ball lived without the benefit of a cleaning lady, and he was always in an unkempt condition. He padded about in a dirty bathrobe when clients called to buy liquor and he spent most of his time in bed with beautiful young women, a bottle of booze, and a plate of fried chicken on the bed table at all times. His only greeting to customers was: “Got the cash?” When the client produced the necessary money, Ball whistled to his black handyman to bring forth the liquor shipment. Often as not the uncaring Ball returned to his bed and the arms of his lover, continuing his lovemaking, oblivious to the gaze of his caller.

Ball was a large, big-boned man, well over six feet, who was muscular but overweight, thanks to his ravenous eating habits. He was expert with a revolver and carried one with him at all times, on occasions whipping out this weapon and firing a practice shot or two to impress witnesses with his marksmanship. In the late 1920s, Ball opened his crudely appointed saloon, The Sociable Club, about fifty feet back from U.S. Highway 181. He developed a liking for alligators and bought five, placing them in a large cement pool behind his club. He would, after a night of drinking, take his best customers outside and amuse them by throwing large chunks of meat into the pool and hoot and holler as the roaring beasts jawed the food, their thrashing tails violently churning the murky water.

For the more sadistic of his friends, Ball arranged his own little horror shows. He kept stray dogs and cats in a pen near the pool and he would take these poor creatures out of the pen and hold them over the pool, teasing the always hungry reptiles and terrifying the animals. Tiring of the game, Ball would throw the strays into the pool where they would be torn apart by the alligators. As he brutalized these animals, he himself became more and more brutal. He shouted instead of talked and threatened anyone who disagreed with him. Yet Ball managed to keep employed a steady stream of beautiful barmaids, radiant young ladies he reportedly paid extremely well and all of whom, it was said, became his mistresses. These women came and went with alacrity which aroused the suspicions of a local constable and neighbor of Ball’s, especially when such favorites as Hazel Brown and Minnie Mae Gotthardt disappeared.

When asked by the constable why the girls had suddenly vanished, Ball exploded and pulled his revolver, shoving this into the constable’s face and threatening to kill him if he went on probing into his affairs. The constable, afraid for his life, did not report the incident. This was not the case with Texas Ranger Lee Miller. When relatives asked police to investigate the disappearance of Hazel Brown in the fall of 1938, Miller and several deputies went to Ball’s roadhouse. They entered the Sociable Inn on Sept. 24, 1938. Ball greeted them affably and then asked if they wanted some beers. “No, Joe, we’re here to have you answer some questions about Hazel Brown.”

The saloon keeper shrugged and then walked behind the bar. “Then, I’ll pour one for myself.” Instead of pouring a beer, Ball went to the cash register and opened the bottom drawer. He pulled out a revolver and the officers, thinking he was about to fire at them, pulled out their own guns and aimed these at Ball. The saloon owner gave them a crooked grin, then put the revolver to his temple and squeezed the trigger, blowing off the top of his head. Later, the deputies found hunks of human flesh floating in a water barrel behind the house, and in the pool where the alligators swirled, there was a trace of blood. Clifford Wheeler, the terrified handyman who worked for Ball, admitted that his employer had murdered many young women and two of his own wives, that he had witnessed Ball shoot one of his wives and his subsequent chopping up of her body and the feeding of her remains to his alligators. Wheeler said he did not dare say a word to authorities about Ball since his employer said he would kill him. He was given a four-year prison sentence as an accessory to murder.

No clear number of Ball’s victims was ever recorded but it was estimated that Joe Ball killed at least twenty women. Most of these young women had been impregnated by the killer and he murdered and dismembered them when they began to demand that he marry them. He did marry two of his victims, but he tired of these ladies and dispatched them to the alligator pool. “Joe, he weren’t no marrying man,” Wheeler told police.

Baniszewski, Gertrude Wright, 1929- , U.S. A native of Indianapolis, Ind., Gertrude Baniszewski lived with her three children Stephanie, Paula, and Johnny, surviving on a meager income. To make ends meet Baniszewski took in children for the summer to earn extra money. In 1965, Baniszewski agreed to board Sylvia Likens, sixteen, and her sister Jennie, fifteen. Jennie Likens would be no problem, the housewife believed since she was crippled and could get about very little. The parents of the two sisters worked in a circus and paid Baniszewski $20 a week to take care of their children. During the first week of their stay, the two girls were fed little, receiving a few slices of toast in the morning and no lunch. A bowl of soup was their only supper. At the end of the first week, Baniszewski dragged both girls to an upstairs room of the house and mercilessly beat them, screaming that she was boarding them “for nothin’!”

The hardened housewife, though receiving weekly payments from the Likens’ parents, resented having the two girls in her home and cursed them whenever they were in her presence. A deep-seated streak of sadism began to manifest itself whenever she was near them; she struck out at them, hitting them so hard that her hands stung from the impact, she later admitted. She reserved her most sadistic treatment for the older girl, Sylvia, whom she beat regularly and then took to paddling on the bare buttocks with a board that left scars. Baniszewski then began encouraging neighborhood children and her own offspring to beat the poor girl, who begged them to stop without relief. The housewife then ordered the other children to put out burning cigarettes on the girl’s arms and hands. One of Baniszewski’s children, Paula, whipped into a frenzy of hatred by her mother, beat Sylvia so hard that she broke her hand which had to be put into a cast. The Baniszewski girl then used the cast to beat Sylvia on the head.

Baniszewski then decided that Sylvia Likens was a whore and tied her up in the basement, releasing her only to beat her and then force her to dance naked in front of other children. Directing a dim-witted neighborhood boy, Ricky Hobbs, needles were heated and used to brand the girl’s stomach with the words: “I am a prostitute and proud of it.” This horrible torture completed, Baniszewski then released the full fiendish fury of her nature, beating the girl, slamming her head against the basement wall with such force that Sylvia Likens died from the blow. The housewife panicked and called police, telling them that Sylvia had run off with a gang of boys, then returned and was mutilated and killed by them; she had found the poor girl in her basement. Her young children repeated this story to investigating officer Melvin Dixon. As Dixon was about to leave, Jennie Likens hobbled forward and whispered to him: “Get me out of here and I’ll tell you the whole story.”

The officer took the girl away and quickly learned the truth about the vicious Gertrude Baniszewski. She was charged with murder and convicted, given a life sentence. Baniszewski won a new trial on appeal but was again convicted and sent back to prison to serve out a life term. In all of the many interviews conducted with this murdering sadist, the housewife has but one excuse for her slaying of a defenseless girl left in her care: “I had to teach her a lesson.”

Bankston, Clinton, Jr. (AKA: Junebug), 1971- , U.S. When it happened, everyone who knew him expressed the greatest surprise. “This all did shock me. He didn’t seem the type,” said Agnes Freeman, a neighbor in the Nellie B. Apartments of Athens, Ga., northeast of Atlanta. Clinton Bankston lived with his mother in this deteriorating section of Athens, an area of high unemployment and gang activity. Bankston was a high-school dropout who spent most of his time riveted to his television. His perceptions of the world were shaped by the images of violence on prime-time television.

On Aug. 15, 1987, Bankston committed a real-life crime so horrible and senseless that its barbarity eclipsed anything law enforcement officers of this small Georgia city had ever encountered.

Robbery was foremost in Bankston’s mind when he entered the home of Sally Nathanson in the fashionable Carr’s Hill section of Athens. Nathanson and her visiting sister, Ann Orr Morris, who lived in an adjacent house, were found dead. Her 22-year-old adopted daughter, Helen Nathanson, was later found lying dead in one of the bedrooms by police investigators. All three had been savagely butchered with a hatchet.

The mutilated bodies could be positively identified only through the efforts of the state crime lab in Atlanta. Athens Police Chief Everett Price conducted a thorough investigation and was able to link the murders of the three women to a similar crime committed against two elderly people the previous April. Items belonging to the earlier murder victims, Glenn and Rachel Sutton, had been found in the Bankston apartment. Bankston was arrested on Sunday morning near his grandmother’s house on Moreland Avenue.

District Attorney Harry Gordon urged the courts to try the 16-year-old Bankston as an adult for the murders of five people. The Supreme Court of Georgia, however, ruled that underage offenders convicted of murder could not receive the death penalty. Bankston pleaded guilty, citing insanity as his defense. On his seventeenth birthday, the quiet boy who liked to ride around the neighborhood on his bicycle received five consecutive life sentences.

Bannon, Charles, 1909-31, U.S. In 1931, Bannon became only the eighth white man to be lynched in North Dakota following his slaying of a rural family of six. Bannon worked as a hired hand on the farm of A.E. Haven near Shafer, N.D. In February 1930, Bannon slaughtered the six-member Haven family and buried their bodies in the barn. He continued to live on the farm for nine months during which time the murdered family was not missed. Bannon was apprehended in November when he attempted to sell some of the Haven livestock at a local market. He was questioned in the family’s disappearance and, after the bodies were found, charged with their murders. Bannon was lynched in February 1931.

Barber, Susan, prom. 1981, Brit. Barber was an Essex housewife engaged in a torrid love affair with her husband’s best friend in May 1981. Her lover’s name was Richard Collins, and the tryst had gone on for nearly eight months before the cuckolded husband came home unexpectedly one day to find them both in his bed. Michael Barber reacted violently. He beat his wife and threw Collins out of the house. But this did not cool his wife’s ardor.

The next day Susan slipped a deadly weed poison known as Gramoxone into his steak and kidney pie. In small doses, Gramoxone is deadly to humans. Death is brought on by fibrosis of the lungs, which makes breathing all but impossible.

Michael Barber was admitted to Hammersmith Hospital in London where he was diagnosed as suffering from pneumonia and kidney failure. Upon further examination doctors concluded that Barber was afflicted with Goodpasture’s Syndrome, a rare nervous disorder. After he died, a pathologist named David Evans conducted the post-mortem. He was not convinced that the cause of death was natural. Blood samples were taken and sent over to the National Poisons Unit and to the company which had manufactured the weed killer. A trace of paraquat, a toxic herbicide, was found in each instance. Based on this chemical analysis, Mrs. Barber and Richard Collins were arrested in April 1982 and charged with murder. Collins received two years’ imprisonment, and Susan Barber, who by this time was no longer interested in her former boyfriend, received a life sentence.

Bardlett, William, 1951- , U.S. Without an apparent reason a 25-year-old elevator repair man named William Bardlett borrowed his sister’s .22-caliber pistol and killed three family members on Nov. 25, 1976. The Thanksgiving Day tragedy on Chicago’s West Side was a grim reminder of the random violence plaguing big city ghettos.

In this case Bardlett murdered two nephews, 9-year-old Dwayne, and 2-year-old Cecil Jr., and his brother-in-law Cecil White, Sr. White and the two boys had gone to the Bardlett home to share a Thanksgiving dinner, believing that William was at work. Bardlett burst into the Harding Avenue apartment and shot White and his son before fleeing. Police later found the revolver underneath the body of the 2-year-old and spent shell casings strewn around the apartment. Officers from the Shakespeare Avenue Police District arrested the suspect at his sister’s residence when he stumbled in without warning during a routine interrogation.

Bardlett was brought before Judge William Cousins on Nov. 28, 1978, and charged with murder. He was declared unfit for trial, and the case continued. He appeared before Cousins again on May 29, 1979, and was remanded to the Department of Mental Health for a fitness hearing. On Nov. 6, Cousins ruled him Not Guilty by reason of insanity in a bench trial. However, in a separate ruling handed down on Dec. 17, the court found the defendant not in need of hospital treatment but decided that he should visit the Isaac Ray Center for periodic mental health checkups. William Bardlett was back on the streets.

Barlow, Kenneth, 1919- , Brit. Elizabeth Barlow was pronounced dead in her bathroom on May 3, 1957, by a doctor called to her home at Thornbury Crescent, Bradford. He had been summoned by Kenneth Barlow, Elizabeth’s husband, who told the physician that he discovered his wife in the bathtub, her head beneath the water. He had tried artificial respiration, he said, but it did no good. At first authorities believed that the dead woman, known to be ill and in a weakened condition, had suffered an accidental death, but the doctor who first examined the body took note that the dead woman’s eyes were dilated. Also, at a later postmortem, several injection marks on the buttocks of the corpse were detected. Officials found hypodermic syringes in the Barlow residence, but this was not considered unusual since Barlow was a male nurse.

Police were suspicious from the beginning, noting that the pajamas Barlow had been wearing when the doctor arrived were not wet, in spite of his claim of seizing the dripping body and giving it artificial respiration. Also, detectives calculated, a drowning person would make some sort of splashing movement that would soak the floor about the bathtub, but the floor was dry when the doctor first arrived. Barlow was charged with murdering his wife, but he insisted that he loved her, saying that he did not have a reason in the world to kill her. (It was later learned that Barlow’s first wife had died less than two years earlier at the young age of thirty-three, but her death had been attributed to natural causes; this death was never revealed in Barlow’s trial.)

At Barlow’s trial before Justice Diplock at the Leeds Assizes, the most damning statements came from Harry Stork, who had worked with Barlow two years earlier. He recalled how Barlow had boasted of discovering the perfect murder weapon, an injection of insulin which would quickly be dissolved in the bloodstream and be undetectable. Moreover, authorities at St. Luke’s Hospital in Huddersfield where Barlow worked, reported that three ampoules of ergotamine had been discovered missing from the medical supplies. Involved statements from medical authorities then argued whether or not insulin was injected into the dead woman, although some traces were found in the body, according to one report. The defense, headed by Bernard Gillis, countered that Elizabeth Barlow, realizing that she was drowning, and in a state of utter panic, released a massive discharge of insulin into her own bloodstream. The prosecution made short work of this preposterous and obviously desperate claim by quickly proving that, for the dead woman to have done so, her pancreas would have had to produce in seconds more than 15,000 units, a physical impossibility.

It was Barlow’s own darkly jocular talk with patients and nurses about the perfect murder that eventually brought him down. In addition to Stork, a nurse named Waterhouse at East Riding General Hospital, told the court how Barlow explained that insulin could kill a person without a trace. Barlow had also told a patient, Arthur Evans, then at Northfield Sanitorium in Driffield, Yorkshire, where Barlow was then working, that he could inject insulin into someone and that no one would ever know that this was the cause of death since it could not be traced. The jury stayed out for only a short while before returning to find Barlow Guilty. He was sent to prison for life.

Bartlett, Helen, prom. 1959, U.S. After her first husband died in 1940, Helen met Alfred Babin. They were married during the war and lived together until his death in 1956. Helen Babin discovered his body. She notified the police, explaining that she had found him in his bath lying face down. During the day, she said, Alfred had been drinking heavily. The coroner reported that Mrs. Babin’s story was indeed true because a large quantity of whiskey had been found in his stomach. Husband number two left behind a $69,000 insurance policy.

During her short period of grief, Babin met 69-year-old Wright Bartlett, a veteran with an assured income of disability payments, who was recuperating from a long illness at the Veterans Hospital. They were married in 1959, and, at his wife’s suggestion, Bartlett agreed to go on a long honeymoon to Texas and Florida. By this time insurance investigators became suspicious of Helen’s motives–she had recently insured her husband’s life in excess of $110,000.

Several months later the newlyweds returned to Buffalo, where Bartlett complained of poor health. He explained that his wife had fed him sandwiches instead of the hot meals to which he had been accustomed. By this time police had entered the case. Under heavy questioning Helen Bartlett admitted to murdering her second husband, Babin, by holding his head under water in the bathtub.

Battice, Earl Leo, 1903- , U.S. A four-masted schooner named the Kingsway set sail from Perth Amboy, N.J., in 1926, bound for the Gold Coast of Africa where the skipper was to deliver a load of lumber. The Kingsway, a rusting, barnacle-infested hulk, was manned by a sullen, suspicious-looking crew and a captain named Lawry.

The ship dropped anchor in Puerto Rico. Lawry went ashore and recruited 23-year-old Earl Battice who signed on as a cook. Battice insisted on taking his wife Lucia on the long voyage, but Lawry said no, reasoning that one woman among a crew of men would cause trouble. Battice refused to compromise and at length the captain, with trepidation, agreed to hire them both.

What Lawry did not realize was that his cook never intended to bring his wife aboard. It was his mistress Emilia Zamot, a poor Creole girl from the streets of San Juan that he wanted to take with him. The jealous wife got wind of this scheme, however, and drove Zamot from the ship.

The Kingsway slipped out of the harbor of San Juan on Dec. 15. Battice proved to be an excellent cook and his wife a pleasing addition to the crew. But after several weeks, Lucia became enamored with the burly German engineer Waldemar Karl Badke, whom everyone feared. They began conducting an affair, flagrantly, and without regard for the cuckolded cook.

The situation became intolerable for Battice, but there was little he could do. His fellow crewmen held him in low regard, and the captain was powerless to intervene, for Badke was feared and respected, and any attempt to thwart him might end in mutiny. Both captain and cook were effectively emasculated by the time the ship approached Monrovia.

Battice finally took matters into his own hands. On Feb. 4, 1927, he seized a razor and assaulted his wife in the storeroom where she was with Badke. It was a surprising gesture from one as docile and timid as Battice. The other crew members now felt some grudging respect for their cook, who was placed in irons by Captain Lawry. Lucia lingered on for seven days before succumbing to her wounds, but during that time, she confided to the captain that Battice had planned her murder in Puerto Rico. When she finally died, her body was dropped over the side of the ship.

Lawry completed his business in Monrovia and headed back to the U.S. amidst growing fears among the crewmen that Battice had placed a deadly curse over them all. Four men became violently ill from the food prepared by the new cook, an African tribesman named Codgo.

Lawry removed Battice’s leg irons and returned him to the kitchen. The Kingsway reached the coast of the U.S. in August 1927. The year-long voyage, filled with so many perils, had at last ended and Battice was arrested and tried for second-degree murder. He received a ten-year sentence at the Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta.

Bayly, William Alfred, 1906-34, N. Zea. Ever since William Bayly’s father sold his farm in Ruawaro, N. Zea., to Samuel Pender Lakey, there had been bad feelings between the two. Then Bayly bought property next to the Lakey dairy farm and moved in. At first their petty disputes involved land boundaries and sheep-grazing rights, but over the years the problems took on more serious overtones. “You won’t see the next season out, Lakey!” Bayly had threatened on one occasion.

The threat was not an idle one. On Oct. 16, 1933, Mrs. Christobel Lakey was found floating face-down in a duck pond. Her husband had disappeared, and Bayly volunteered a possible solution to the police. He said that the couple had been quarreling a lot lately, and that Samuel had probably murdered his wife and then run away. The police were suspicious. They searched William Bayly’s property and uncovered evidence of a body. Bone fragments were scattered piecemeal on the farm. They also found Lakey’s watch and cigarette lighter. Blood in Bayly’s tool shed was clear evidence to investigating police officers of recent foul play.

Despite his denials, Bayly was found Guilty of murder after a month-long trial in Auckland. He was executed at the Mount Eden jail on July 30, 1934, just a few days after his twenty-eighth birthday.

Bean, Harold Walter, 1939- , U.S. Describing his scheme to get rid of a wealthy elderly widow, Harold Walter Bean told a cohort, “We’ve added another round to our bag of tricks…Murder.”

Dorothy Polulach, an 81-year-old widow, lived quietly as a recluse in her expensive South West Side Chicago home, which was barricaded with locks and elaborate security systems to protect her costly antiques and jewelry. One afternoon in mid-February 1981, a man in priest’s garb stopped to talk with her as she shoveled snow off her front walk, suggesting that a lady her age should have help, and offering to bring someone to assist her soon. On Feb. 17 the priest returned with a companion. Recognizing the one man, Polulach let them in. Bean, disguised as a priest, began to beat the elderly woman, who fought back. His accomplice, Robert Byron, also called “Spook,” quickly filled his briefcase with jewelry and ransacked the house for other valuables, for the killing was intended to look like a robbery. Bean knocked Polulach down, then handcuffed her and dragged her upstairs, shackling her ankles and breaking her glasses before putting a .38-caliber pistol to her head and shooting her twice. Her body was discovered three days later by Phyllis Mahl and her husband. Mahl called Polulach’s stepdaughter, Ann Polulach Walters, in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., to tell her of her stepmother’s death. Though Walters appeared shocked, actually she had hired Bean to murder Polulach as she would inherit as much as $750,000 and the Polulach home when her father’s second wife died.

Detectives Tom Ptak and Mike Duffin took over the case. Mahl told them that Walters was exhibiting strange behavior, like hiding pastries at the funeral services and finding mysterious messages in the wake register. Then a man named Jimmy Steele was heard to brag in a Cicero tavern about the slaying, saying the victim had been shot twice in the head–information only the killer could know. Ptak and Duffin questioned Steele, learning that he was the stepson of Harold Bean. Steele then confessed that he had rented the priest’s outfit for Bean and had heard him talking to an attorney about Walter’s potential inheritance. Bean, a master of disguise and a criminal since he was sixteen, had once hidden from the FBI for six years. With these leads, the detectives went to visit Walters, now enmeshed in witchcraft rituals to exorcise her murdered stepmother’s spirit, and asked her to look at some mug shots, including one of Bean.

Walters’ response was, “You know the whole thing, don’t you?” She and her husband, Wayne Walters, confessed and were charged with murder and conspiracy on Apr. 5, 1981. Bean was arrested in a remote area of the Palos Hills Forest Preserve on Apr. 25, and Byron soon after, charged with helping Bean break into the Polulach home. Robert Danny Egan, who drove the getaway car, testified against Byron and Bean and received a seven-year prison term for his part in the crime. In October 1981 Bean and Byron were convicted of murder and sentenced by Judge James M. Bailey to die in the electric chair. Walters pleaded guilty to plotting the murder and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Wayne Walters received a seven-year prison sentence for conspiracy.

Beard, Arthur, prom. 1919, Brit. A notable criminal trial involved night watchman Arthur Beard, who raped and strangled 13-year-old Ivy Lydia Wood on July 25, 1919, in Hyde, Cheshire.

On Oct. 6, 1919, Justice Clement Meagher Bailhache sentenced Beard to death. An appeal was immediately filed, and the verdict in the first trial was overturned on the grounds that Beard was incapable of forming the intention to murder because of his severe state of drunkenness at the time of the assault. “Malice aforethought” was therefore absent, and the court ordered the charge reduced to manslaughter.

The Crown was displeased with the verdict, and Lord Hewart and Sir Charles Matthews brought the matter before the House of Lords. Lord Frederick Edwin Birkenhead, Lord Haldane, and Lord Reading reversed the judgment on Mar. 5, 1920. The judges argued that Beard had not been too drunk to rape the child. Lord Birkenhead re-established the original charge of murder but ruled that Beard could not be executed. The prisoner began serving a life sentence.

Beattie, Henry Clay, 1884-1911, U.S. In 1911, the city of Richmond, Va., was rocked with news of a bloody slaying five miles outside the city. Henry Clay Beattie, on the night of July 18, arrived at the home of Thomas E. Owen, which was off the Midlothian turnpike. Breathlessly, he pointed to his open auto. The Owens moved cautiously to the car. In the back seat they saw Mrs. Louise Beattie. The top of her head had been blown off.

Beattie told police that he and his wife had been stopped by a tall highwayman who waved a gun in their faces. The bearded man had shouted at them: “You had better run over me… You have got all the road!” or, at least, that’s what Beattie claimed the man said. Beattie tried to drive around the tall highwayman, he said, but the man raised his weapon and fired just as the car passed him. Mrs. Beattie was killed instantly by the blast and the killer fled, howling through the nearby woods. Or had he been laughing? Beattie could not remember, he told police. The gun? Beattie remembered stopping the car, running after the man, and wresting the weapon from him before the murderer escaped. He could not recall where he had thrown the gun.

Mrs. Beattie was buried before the coroner’s jury could make up its mind about her demise. That was decided by Detective L.L. Scherer, who found the murder weapon alongside the C&O Railroad tracks. Tracing its sale, Scherer discovered that a Paul Beattie had purchased the gun for H.C. Beattie. The husband was quickly arrested and tried for the murder of his wife.

Beattie emphatically denied his guilt, although a staggering case had been built against him. Even after he was sentenced to die in the electric chair, the convicted man refused to admit to the slaying. The 27-year-old was led into the death room on Nov. 24, 1911, still mumbling about the tall, bewhiskered highwayman who had murdered his wife. (It was eventually learned that Beattie had been a student of the Old West and that he had described a photo of Jesse James which was kept in his album of gunslingers.)

Not until he was executed was the truth learned from Beattie himself. His religious advisors, the reverends J.J. Fix and Benjamin Dennis, provided newsmen with Beattie’s handwritten confession which they had witnessed the day before his electrocution. It read:

“I, Henry Clay Beattie, Jr., desirous of standing right before God and man, do on this, the 23rd day of November, 1911, confess my guilt of the crime charged against me. Much that was published concerning the details was not true, but the awful fact, without the harrowing circumstances, remains. For this action I am truly sorry, and believing that I am at peace with God and am soon to pass into His presence, this statement is made.”

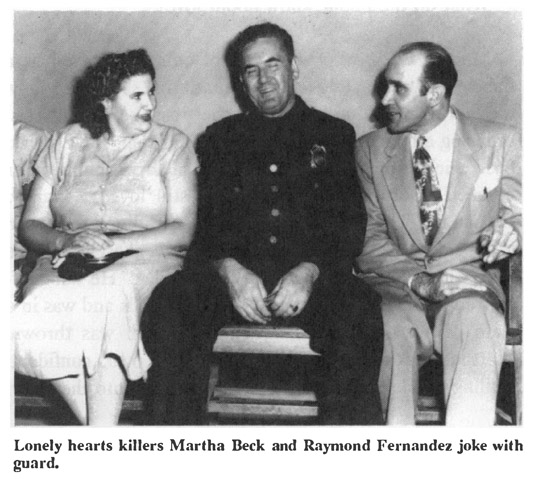

Beck, Martha Julie (or Jule), 1921-51, and Fernandez, Raymond Martinez (AKA: Charles Martin), 1914-51, (AKA: The Lonely Hearts Killers), U.S. Fernandez, born in Hawaii of Spanish parents, was an adventurous youth who reportedly served with British Intelligence during WWII, winning commendations. He was wounded in the head in 1945, an injury that altered his personality from sanguine to phlegmatic, according to one report, and sent him on a criminal career in which he bilked well-to-do widows out of their savings after proposing marriage. He was tall and thin, covering his almost-bald head with a cheap black wig. But the love-desperate women who fell for his pedestrian pitch of woo, thought of him as an irresistible Latin lover. In the words of one newsman: “He was a rather seedy Charles Boyer.” Fernandez found his victims in the then-popular lonely hearts clubs or through the lonely hearts columns of newspapers. He even married several women, having one family in Spain, another in the U.S., and according to some reports others still in Mexico and Canada.

One of the lovelorn ads Fernandez answered turned out to have been placed by Mrs. Martha Beck, a registered nurse who ran a home for crippled children in Pensacola, Fla. When the sleazy Lothario arrived on Mrs. Beck’s front door in 1947, he was taken aback by the obese woman standing before him. She welcomed him with open arms and Fernandez the con man, for some inexplicable reason, fell in love with the unattractive Martha. Mrs. Beck, who had been divorced since 1944, lavished attention on Fernandez who confessed his swindling ways to her. To his surprise, she not only approved of his crooked pursuits but asked to be part of his widow-bilking schemes. The couple traveled northward, stopping in cities along the way to answer lonely hearts advertisements and mulct the lovesick widows.

Their usual procedure was for Fernandez to woo and win the lovelorn lady and, during the course of a brief courtship, introduce Beck as his sister. Then, following the wedding, Beck would move in with the newlyweds, and the looting of savings and jewelry quickly ensued. Most of the women, more than 100 of them, were in their late fifties or sixties, but Beck could not bear to be in the same house with Fernandez and a new wife, knowing he was making love to another woman. Her jealousy grew whenever the victim was young and attractive, such was the case with Mrs. Delphine Dowling of Grand Rapids, Mich. Mrs. Dowling, twenty-eight, had a 2-year-old daughter, Rainelle, and was apprehensive of Fernandez, allowing him and his “sister” to move into her home but delaying the nuptials with her newly found Latin lover until she was convinced her spouse-to-be was sincere. Beck found it impossible to sleep in the next room while her own man was on the other side of the wall with a younger, more attractive woman. They would not wait for the wedding ceremonies, Beck told the docile Fernandez. Mrs. Dowling and her daughter had to go. Both disappeared in January 1949.

Neighbors, noticing the absence of Mrs. Dowling and her daughter, called police and when officers arrived at the Dowling residence, Beck and Fernandez calmly invited them inside, telling them they had no idea where Mrs. Dowling and her child had gone. Police thought the pair looked suspicious and insisted that the home be searched. Beck shrugged and Fernandez waved them into the parlor. Investigators found a fresh patch of cement on the floor of the basement. “It’s the size of a grave,” said one officer and they soon unearthed the bodies of mother and child. The Lonely Hearts Killers, as Beck and Fernandez were quickly dubbed by the press, collapsed immediately, freely admitting the murders and then bragging that there were as many as seventeen other victims they had killed. Beck, glorying in her publicity, explained that she dosed Mrs. Dowling with sleeping pills, but the young woman was strong enough to resist the drugs and Fernandez shot her in the head. They originally did not plan to murder the little girl. When she cried for her mother, Martha Beck said, as if displaying her humanity, they bought her a dog. But the child continued to whine so Martha dragged her into the bathroom, filled the tub, and held the girl beneath the water until she drowned.

Fernandez and Beck, of course, were well aware of the fact that the state of Michigan had no death penalty and undoubtedly reasoned that they would be imprisoned and later be paroled, in spite of their heinous crimes. (This was the same tactic earlier employed by Fred R. “Killer” Burke, one of the machine gunners at the 1929 St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.) With that comforting thought in mind, the pair bragged about their other murders. “I’m no average killer,” Fernandez boasted. “I only got five hundred off the Dowling woman,” he said disappointedly, “but take Mrs. Jane Thompson, I took six thousand off of her.” He explained how he married Thompson and took her to Spain where he murdered her, poisoning her with digitalis. He then returned to the U.S. to explain that he and his poor wife had been in a train wreck and she had been killed. The Thompson family did not bother to check if there had been such a wreck; they merely took his word for it. Fernandez was so convincing a liar that he moved in with Thompson’s mother, Mrs. Wilson, wooed and bilked her and then murdered her, too.

Throughout the long confession, Beck was at Fernandez’ side, chuckling perversely as he droned his litany of murder. She found it all too amusing but was solicitous of her lover. When he began to sweat, he removed his cheap wig. Beck reached over to pat his bald pate dry with her handkerchief, thickly scented with cheap perfume. Then she urged him to continue, as if she were a child begging for a tale to be completed. Fernandez recalled a Mrs. Myrtle Young. He took her to Chicago in 1948 on their honeymoon. He laughed and said: “Poor woman, she died of over-exertion.” Beck could no longer allow Fernandez to hog the limelight. She blurted out her own confessions rapidly, her heavy jowels jiggling as she rattled off murder after murder. One she vividly recalled–there were so many that taxed her memory–involved Mrs. Janet Fay of Manhattan. She and Fernandez had already taken the 66-year-old woman’s last cent, but she was murdered anyway, only because Beck’s jealousy exploded when the old woman cried out for Fernandez as the couple was leaving Fay’s apartment.

Beck was incensed at Fay’s display of affection for her man, and she grabbed a hammer and smashed it down on Fay’s head, crushing her skull. Then Beck said in her best child’s voice: “I turned to Raymond and said, ‘look what I’ve done,’ and then he strangled her with a scarf.” Beck explained that although she had already murdered Fay, Fernandez, out of his deep love for Martha, insisted on taking part in the killing by strangling the lifeless corpse. Both killers were amazed when the state of Michigan abruptly allowed them to be extradited to New York to stand trial for their self-admitted slaying of Mrs. Fay–New York still had the death penalty. Both defendants were tried before Judge Ferdinand Pecora, pleading not guilty by reason of insanity. Psychiatrists examining both of them reported them sane and the trial went ahead. On one occasion, when Beck was being brought into court, she broke away from her female guards and lifted the startled Fernandez out of his chair, kissing him on the mouth and neck and cheeks. She had to be pried loose, screaming: “I love him! I do love him and I always will!”

A jury quickly convicted the pair and Judge Pecora sentenced them to death, their execution to be held on Aug. 22, 1949, at Sing Sing. While awaiting the electric chair, the couple exhanged love letters, sent between the male and female cellblocks. When Beck heard that Fernandez was regaling his fellow prisoners in death row with her eccentric behavior, she exploded, sending him the following message:

You are a double-crossing, two-timing skunk. I learn now that you have been doing quite a bit of talking to everyone. It’s nice to learn what a terrible, murderous person I am, while you are such a misunderstood, white-haired boy, caught in the clutches of a female vampire. It is also nice to know that all the love letters you wrote ‘from the heart’ were written with a hand shaking with laughter at me for being such a gullible fool as to believe them. Don’t waste your time or energy trying to hide from view in church from now on, for I won’t even look your way–the halo over your righteous head might blind me. May God have mercy on your soul.

M.J. Beck

Through appeals filed by their lawyers, Beck and Fernandez managed to postpone their date with the electric chair until Mar. 8, 1951. Fernandez ordered a large meal but, with his death only a few hours away, he could not eat it. He did smoke a long Havana cigar down to a small stub. Then he handed a note to one of the guards, saying that these words would be his last utterances on earth. The note, later widely published, read:

People want to know whether I still love Martha. But of course I do. I want to shout it out. I love Martha. What do the public know about love?

Martha Beck, who was tired of being portrayed as a flabby, fat woman, told a female guard that she would show the world what kind of woman she was; she would resist ordering a feast for her last meal. That said, she ordered fried chicken and fried potatoes and a salad–a double order of each. She announced that she still loved Raymond Fernandez. There existed at Sing Sing a tradition that when two persons were to be executed, the weakest was to be sent to the chair first. This was Fernandez. He was half-carried to the electric chair by several guards and was in a state of nervous collapse when the switch was thrown. Martha Beck followed, walking on her own, confident, smiling as she almost threw her great bulk into the chair.

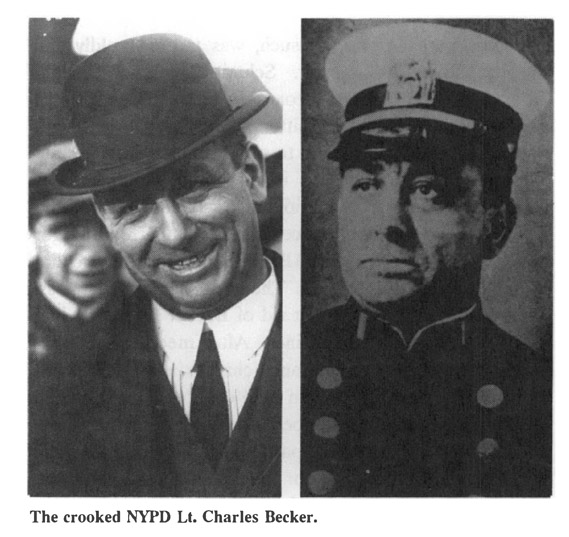

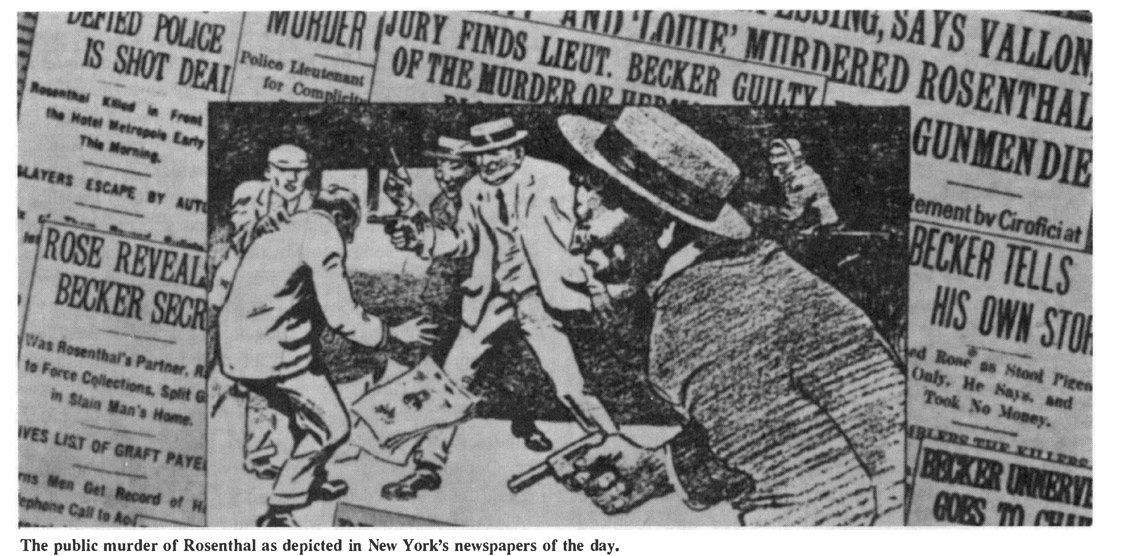

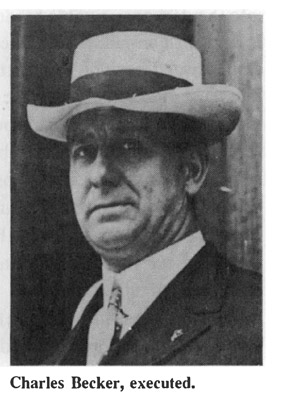

Becker, Charles, 1870-1915, U.S. The image of the crooked cop without conscience, compassion, or remorse for his ruthless acts was devastatingly summed up in the character of Charles Becker, a lieutenant of the New York Police Department. Becker made a fortune by protecting New York City gamblers until he decided one of these sharpers should be killed, and he ordered the murder of Herman Rosenthal. This blatant slaying by hired killers under Becker’s command eventually led Becker to the electric chair, but long before that, a decade before, Becker ruled the gambling empire of New York City. His word was law–to break his law was to face unendurable punishment, ruination, and early death. Becker, the corrupt cop, came into being not at his source environment, but in the heart of New York City, or, to be exact, in its Tenderloin, the most exciting, dramatic and vice-ridden area of America at the time. This land of payoff and kickback was far from the green, comfortable hills where Charles Becker was born on July 26, 1870. The sixth child of ten, Becker was born in Callicoon Center, N.Y., a hamlet in the foothills of the Catskills in Sullivan County. He was a large boy and did not shirk fights. At home he was truculent and slow to obey his parents. At school he was even slower to complete assignments. Yet his honesty was never questioned and he excelled in athletics and manual labor. By the time he was eighteen, he had developed a tall, powerful body with broad shoulders, massive arms, and enormous hands that, when doubled into fists, were like the flat sides of two stonemason hammers.

At this time Becker bid farewell to his family and rural life, and traveled to New York City to see a German baker who was a friend of his father’s. The baker gave him a job and a room above the bakery, which was in the German section of the city in the old Seventh Ward. To the south was the Bowery and to the north was the wealth of Manhattan which beckoned like a beacon fire to the ambitious Becker. After a brief affair with the baker’s daughter, which found Becker confronting the baker and being ordered from his establishment, the youth, then nineteen, went to work as a waiter at The Atlantic Gardens, a sprawling beer garden which had once been the pride of the German community, where free music and excellent nickel beer was offered to a generally middle-class patronage. With the ending of the Civil War, this great spa had declined so that by 1889, when Becker went to work there, the place was populated at night by gamblers, thugs from the Bowery, and prostitutes plying their trade. The well-built, no-nonsense Becker found himself knocking the heads of thugs who created disturbances. He soon built a reputation as a man who could best almost any plug-ugly with a mind to starting trouble.

The job of bouncer was offered to Becker, and the 21-year-old accepted, working in another beer garden. Here he became known as a brutal overseer no thug would think to anger. Even the most fierce of the early day New York gangsters such as Edward “Monk” Eastman gave Becker a wide berth. Eastman not only grew to respect the quick-fisted Becker but he befriended him, taking him to his political sponsor, Timothy “Big Tim” Sullivan, the powerful head of Tammany for the entire East Side of Manhattan. Sullivan used Eastman and his fearsome gang as strikebreakers and political strong-arm thugs who made sure that every election was a Tammany triumph. Tammany also dictated the politics for the entire city at that time and Sullivan lived like a czar, making appointments to political and police posts at will and whim. Sullivan sized up Becker as someone above the status of an ordinary thug, a young man with intelligence and street sawy–one who not only would be loyal to Tammany but to Sullivan himself. The police force, Sullivan concluded, was the right spot for Charles Becker. In 1893 Becker paid a $250 fee to Tammany for his appointment to the police force. This was customary and was publicly known and excused, at least by the political sachems who ran things, as a way of assuring the fact that men known to the organization, who were screened as good candidates by Tammany and were not strangers with criminal records, were thus brought onto the force. The screening process cost Tammany money and the applicant was merely paying back the organization’s investment. Such money was no small investment. At the time, $250 was one-third the yearly pay of an average cop on the NYPD. The force at that time had more than 5,000 men on the streets, all of them white and most of them, like Becker, Catholic.

The type of police officer the NYPD then hired and kept on the force was not very much different than the type of thug who worked for Monk Eastman, except that they wore uniforms and never openly committed theft. Patrolmen were burly, big men who used their long nightsticks to club anyone who got in their way, either innocent citizen or hooligan. Even to ask a question of the beat cop in those days was to risk being poked in the chest with his stick and hustled down the street for bothering an officer of the law. The man who established and maintained this hardboiled attitude was Inspector Alexander “Clubber” Williams, who was infamous for his brutality and ruthless manner. It was the grafting Williams who gave the wide-open vice district its name. He had been serving in a West Side precinct in the 1870s and when he was transferred to the choice area, he remarked to a newsman: “I’ve been living on chuck steak for a long time. Now I’m gonna get me some of the tenderloin.” Williams supervised an area that stretched approximately between Twenty-third and Forty-fourth streets and between Third and Seventh avenues, this being the old Twenty-ninth Precinct. Here could be found the best hotels, the finest theaters and restaurants, as well as hundreds of posh gambling dens, bordellos, and vice dens of all sorts, a plum for grafting policemen such as Williams.

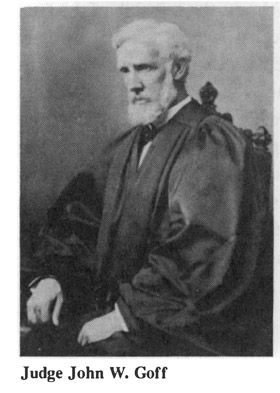

During the Lexow Committee Hearings, which began just about the time Becker joined the force, Inspector Williams was the focal point of the investigation into police graft. Prosecuting counsel John Goff, who, ironically, was to preside over Becker’s own first murder trial almost twenty years later, revealed that Williams had more than $250,000 in the bank, owned a mansion and a yacht, and lived like a king. Williams boldly admitted that he took what he liked in the district he controlled and he was later dismissed from the force, though never prosecuted. His was the enduring image that etched itself into the mind of the ever ambitious Charles Becker. He, too, would someday preside over the Tenderloin and make his own fortune, this he vowed. Long before that time, however, Becker found himself in continuous trouble, so much trouble that he gleaned more press coverage in that day than any other common cop on the force. At first Becker was assigned to the Fulton Street area and later, due to the strings of his mentor, Inspector Williams, moved to the Tenderloin. It was here that he ran headlong into the famous writer, Stephen Crane, who had seen him years earlier on a dark street pounding the face of a helpless prostitute who had failed to pay him off that night.

Crane had established himself as one of America’s finest authors the previous year, in 1895, with the publication of The Red Badge of Courage, and was the toast of New York at the age of twenty-four. He disdained the literary parties and salons, preferring the company of Bowery lowlifes, bums, and apprentice hoodlums and their women, mostly prostitutes. He had long taken the view that the beat cop in New York was nothing more than a thug in uniform and had been writing a series of articles exposing their grafting, brutal ways, communicating with the new police commissioner, Theodore Roosevelt. On the night of Sept. 15, 1896, Crane found himself at the Broadway Gardens, assigned by the editors of the New York Journal to write about the underworld types who crowded the tables there. With him were two streetwalkers of his acquaintance and they were joined by another whore named Dora Clark. At 3 a.m., Crane put one of the girls on a streetcar, and when he returned to the sidewalk, he found the large, lumbering Becker arresting his other two friends for soliciting. Crane stepped forth and said one woman was his wife. Becker, who was later described by Crane as “picturesque as a wolf,” then reached out and grabbed the other girl, Dora Clark, arresting only her on charges of prostitution. As he dragged the girl off, Crane protested and Becker smirked, snarling: “You ain’t married to both of ’em, are you?”

Rushing to the Tenderloin station house, Crane obtained Becker’s name and badge number, then told newsmen that “whatever her character (that of Dora Clark), the arrest was an outrage. The policeman flatly lied!” Crane appeared as a witness for Clark later in court, where Becker insisted that he had seen the woman solicit two men within five minutes. Crane told the presiding magistrate that this was a boldfaced lie, that he had been with the woman for several hours and nothing of the kind happened. Dora Clark then testified that she had been persecuted for several months by Becker and other policemen in the area because she had resisted the advances of a cop named Rosenberg. This officer had solicited sex from Dora and she, thinking he was black because of his swarthy complexion, had replied: “How dare you speak to a decent white woman!” Calling the officer black when he was not was thought by fellow officers to be the worst insult their ranks could receive and Dora Clark had been marked for vengeance.

After listening to the statements, the magistrate, who had recently received a favorable profile by Crane, shocked Becker and dozens of other officers who had lent him support by siding with Crane and accepting his version of the events. Dora Clark was released. Becker had received his first minor setback, but this incident was nothing compared to his next ill-fated news notice. Becker was working the graveyard shift on Sept. 20, 1896, with another officer named Carey when, close to dawn, the two patrolmen saw three men flee from a tobacco shop carrying sacks of loot. They gave chase, shouting for the burglars to halt. Though heavyset, Becker was fast on his feet and he caught up with one of the burglars, bringing him down with one blow from his nightstick. A second burglar outdistanced the pair. Then one of the officers, it was never determined who, shot the third from some distance. This escapade was played up in the press and Becker was hailed as a hero. The dead man, Becker insisted, was a notorious second-story man named John O’Brien. There was talk of giving Becker a commendation and an important promotion until, three days later, the relatives of the slain man identified him as 19-year-old John Fay, a plumber’s assistant. Fay had accidentally stepped in the line of fire which both Becker and Carey knew, Fay’s family claimed, but they assumed no one would inquire about a dead young man they were passing off as a notorious thief. John Fay’s reputation had been tarnished, his relatives said, so that a pair of “gun-happy killers” could make the police force look good in the press. Becker and Carey were suspended for a month and were privately warned by their superiors to make sure of their targets in the future.

By the time Becker returned to his post in the Tenderloin, he was surprised to see Commissioner Roosevelt come into the precinct station to review the men there. He singled out Becker, shook his hand, and commended him for his considerable bravery in taking on thieves face to face but then he turned and told the entire group that they should all be more careful in their treatment of “unfortunate women,” that even these fallen angels had the same rights as law-abiding citizens. In this way, without singling Becker out, Theodore Roosevelt had subtly upbraided him, warned him. But Becker was not a man of subtleties. He proved that when he sought out Dora Clark in October 1896 and beat her until he blackened both her eyes and broke her nose. He was stopped by fellow officers from choking her to death. He left her on the sidewalk, warning her that she would “wind up in the river” if she ever again accused a New York cop of anything. But Dora Clark was stubborn and brought charges against Becker. A police hearing was held, the longest on record up to that time, and Becker got off with a casual reprimand.

It appeared to Becker that his political influence through Big Tim Sullivan was not only intact but would protect him against any pesky citizen daring to challenge his authority. On one occasion Becker arrested a society woman whom he accused of soliciting. She turned out to be perfectly innocent, having said goodbye to one of her lawyers on the street after a meeting in his office. Becker, confronted with the testimony of the lawyer, gave the man his usual sneer, refusing to back down and stating: “I know a whore when I see one!” He was reprimanded and sent back to the street where, a short time later, he arrested another woman who approached him and asked directions to the subway. He mumbled something to her she did not understand and she questioned him again. Annoyed, Becker grabbed the poor woman and ran her into the station house, booking her as a common drunk. She turned out to be the wife of a New Jersey manufacturer. This incident caused Becker’s superiors to slavishly apologize to both the woman and her influential husband, and even Becker’s political sponsor, Big Tim Sullivan, had to step in and persuade the couple not to sue. Sullivan had a quiet talk with his protégé, telling him that he had to be more cautious in the future when arresting women. He had plans for Becker, Sullivan told him, big plans, so it was important that he maintain an unblemished record.

Some time later, however, the easy-to-anger Becker, while on a raid against a gambling house, was shoved by a gambler who boasted of his political influence. Becker, who was alone in the room with the man at the time, pulled a pistol and shot the gambler dead, later claiming that the man puled a gun. No witnesses were present to contradict him but Becker’s superiors again had a quiet talk with him, warning him severely to keep his hand off his gun unless it was absolutely necessary to use it. To make sure that he got the point, Becker was suspended for a month. The hamhock-fisted officer took this time to marry Vivian Atteridge. He had been married briefly in 1905 to a pretty young girl named Mary Mahoney, but she had died nine months later of tuberculosis. The marriage to Atteridge would last until 1905 when Becker would divorce her. Vivian would remarry in 1907, wedding Becker’s brother John who was also a member of the NYPD.

In 1901, Becker came under the direct command of Captain Max Schmittberger, the very man who had exposed the corrupt practices of Inspector Alexander Williams. Though Clubber Williams was no longer on the force, he acted as an adviser to Becker, who had long ago embraced the Clubber’s philosophy of brute force. Becker, by then a roundsman (one status above patrolman, similar to the rank of corporal), was known by Schmittberger to be a Williams partisan and, as such, was treated coldly and suspiciously by his superior. Schmittberger was thought of as a squealer and a turncoat who had exposed his own people to the Lexow Committee and, as such, many high-rankers on the force wanted to see this man disgraced and deposed. It was with this in mind that Commissioner Bingham and later Commissioner Rhinelander Waldo, who had been told by angry police officials that Schmittberger was corrupt, secretly ordered Becker to dig up evidence that would expose Schmittberger. The police captain knew this, of course, and moved to get rid of Becker by having him transferred to another precinct. After meeting with Williams, Becker filed malfeasance charges against Schmittberger. The enraged captain filed countercharges, but all of these charges were dropped after Commissioner Bingham brought the aggrieved parties together and told them to forget their differences for the sake of the department.

For some time, little was heard of Charles Becker. He must have concluded that the ways of Clubber Williams could do little to advance his career and he maintained a low profile for several years, keeping his record clean. Then, in 1904, Becker suddenly received the department’s highest award for heroism which put his name back into the headlines. He had seen a young man in the Hudson River struggling to stay afloat. Fully clothed and without a moment’s hesitation, Becker jumped into the river and pulled the man to safety. He turned out to be an unemployed clerk named James Butler who blubbered his thanks to a grinning Becker before newsmen who had conveniently been called to the scene. Butler praised Becker to the newsmen as one of the bravest fellows he had ever seen, explaining that a plank he was walking on gave way and he fell into the River near 10th Street. But it was only a week later when Butler called up the same newsmen and complained that Becker had reneged on his promise. What promise was that, he was asked. Becker, Butler explained, had offered him $15 to jump into the Hudson so that he could jump in after him and appear to be the great hero. But Becker had never paid him the $15 and now Butler was angry at having ruined his only suit for nothing. Becker denied the whole story, laughing at the idea, which he called preposterous. By then he had his medal and a promotion to sergeant.

A short time later, through his Tammany contacts, Becker was promoted to lieutenant and he began to make his moves against the posh gambling and vice dens of the Tenderloin. One story has it that about 1907, Becker made the rounds of all the big time gambling dens and demanded $15 payment a week for himself even though the gamblers explained that they had already paid their “protection” money. After collecting $150, Becker was called into Schmittberger’s office and the captain told him to put the money down on his desk, explaining that he knew exactly how much he had collected. Becker tossed the money on the desk and Schmittberger handed him back $15, telling him that that amount was his end, ten per cent, and from that day forward he would be Schmittberger’s personal bagman and receive ten percent of everything he collected. Becker the bagman went to work with a vengeance, becoming rich in the course of the next few years. But in 1911, Police Commissioner Waldo decided to crack down on the Tenderloin gamblers after being goaded by scores of enraged reformers objecting to the blatant vice district. Waldo believed that Schmittberger was the core of the rotten apple in the Tenderloin. Years earlier he had, as a Deputy Police Commissioner, met with Becker secretly, ordering him to get evidence against Schmittberger, not knowing, of course, that Becker was Schmittberger’s bagman and heir apparent to wholesale graft in the precinct. Becker, quite naturally, agreed to the secret investigation, sitting as he was in the catbird’s seat, able to provide snippets of information on his captain without ever giving Waldo enough evidence to bring about Schmittberger’s removal.

At the same time Becker made himself look good to downtown superiors by appearing to energetically attack the gambling and vice dens by conducting incessant raids against these places. Yet he went on making enormous illicit profits from the gamblers he was protecting, satisfying both Waldo and his protection-paying gambling dens. In 1911 Becker organized and led 203 raids into the Tenderloin where he and his men made 898 arrests which resulted in 103 convictions, a staggering record that outwardly made Becker look like a law enforcement crusader. But what the record also showed, if one dug deeper, were sentences that amounted to next to nothing. Most of the convictions ended in suspended sentences or small fines seldom exceeding $50. Waldo blamed the court system and corrupt judges for such leniency, and to some extent he was correct, since many judges were then, as before and after this golden age of kickbacks and payoffs, on the take. Becker, however, was the man who manipulated these judicial decisions. He simply ordered his men, when appearing in court, to have loss of memory as to the particulars of the raids they conducted. They conveniently misplaced or lost vital evidence that would have assured strong sentences. Faced with this type of shallow prosecution, judges were compelled to issue light sentences. The whole system worked both ways for Charles Becker.

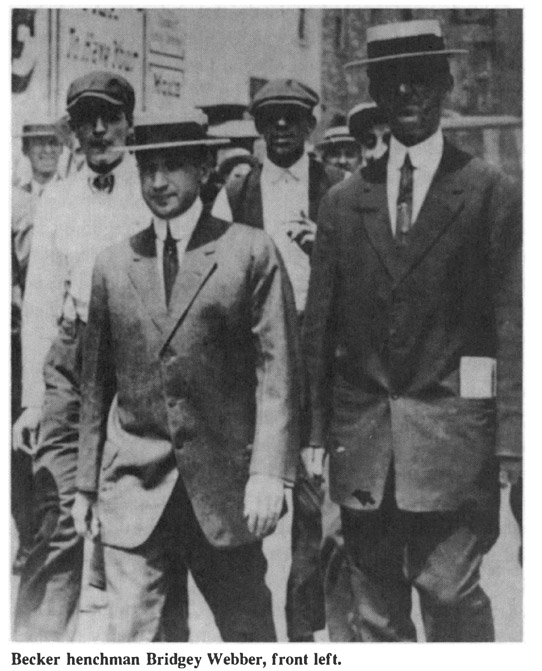

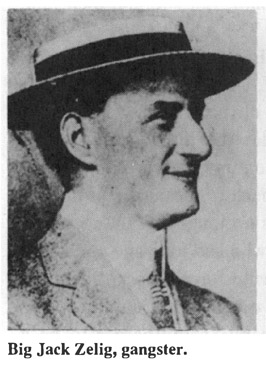

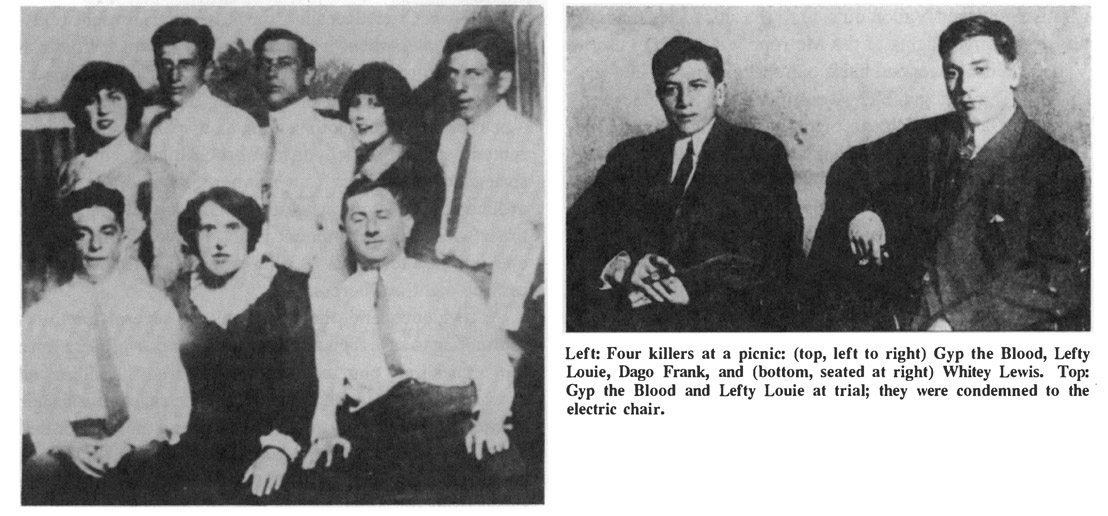

By late 1910 Becker operated autonomously as the head of the gambling squad or, because of the violent manner in which the squad often tore apart gambling dens (those who had been slow to make payoffs), the group known as “the strong-arm squad.” His word was law in the Tenderloin by then and he paid nothing to Schmittberger who had been neutralized and later ousted by Big Tim Sullivan. Becker, after minor payoffs to his own officers, split his payoff take only with Big Tim and this further enriched his own coffers by tens of thousands of dollars. To keep the gamblers and vice lords in line, Becker, through Big Tim, employed the worst gang of thugs in New York to perform beatings and even murder, chores too messy for his own corrupt policemen. Monk Eastman had been sent to prison by then, abandoned by Tammany as uncontrollable and had been replaced by Jacob “Big Jack” Zelig (whose real name was William Alberts), a towering, fierce thug who had been Eastman’s right-hand man, a gangster with much more cunning than Eastman, one who knew how to keep his organization in line. Zelig and his host of killers worked directly under Becker’s orders, going on his payroll but being directed in their nefarious activities by gamblers who took their orders from Becker.

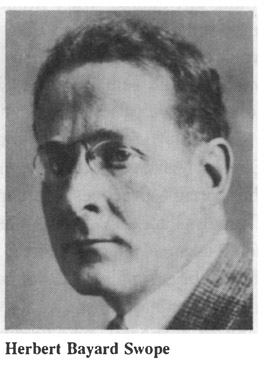

If any of these gangsters ever disobeyed Becker’s dictates, he merely had them arrested for violating the Sullivan Law, a law ironically put on the books by none other than Big Tim when, in 1909, he decided to return to the state senate. A disloyal or disobedient gangster would be dragged into court and charged by Becker’s minions with carrying concealed firearms, thus violating the Sullivan Law. This carried with it a mandatory eight-year sentence. Of course, when this law went into record, the gangsters never carried firearms unless on the job. Becker got around this by simply having his men provide “throw-away” guns or spare pistols and automatics which were supplied by police officers in quickly convicting a gangster who did not cooperate with the system. Herbert Bayard Swope, later the chief journalist covering the Becker-Rosenthal murder, would later write that “Becker was the System. Like Caesar all things were rendered unto Becker in the underworld. Like Briareus he had a hundred arms…and more power in the Department than the Commissioner.”

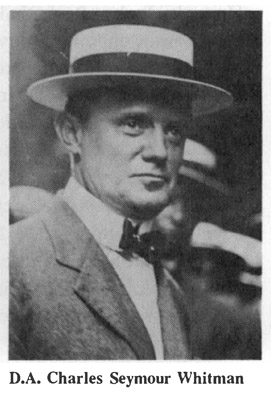

But Becker was not without competition. A number of other lieutenants under his command lusted for his power position and they would do just about anything to come into the good graces of Big Tim Sullivan, the Tammany sachem and real czar of influence and power in New York. Big Tim was many times a millionaire with villas, mansions, yachts, and endless sources of cash; he had been on the take since Boss Croker abandoned his leadership at Tammany in 1901, retiring to the French Riviera with his own millions hustled from the city. Yet Big Tim had no ambitions to retire. He had to have more and more and knew that the Alexandrian philosophy of dividing and controlling his henchmen, Becker included, was the key to the flowing cornucopia of graft. Becker knew this also, that Big Tim would quickly replace him at any time if convenient. So Becker shrewdly began to cultivate certain members of the press as early as 1910, giving crime reporters inside tips on raids and making sure that he and only he received glorification in print. He even went so far as to hire Charles Plitt as his press agent, making sure that the newspapers were informed of his daily activities, or those that made him look like a police hero to the public. Thus for two years leading up to the Rosenthal killing, he overshadowed almost every policeman in the department, except for the commissioner. This caused Becker to undoubtedly become the most disliked member of the department but he was also the most dangerous. As such, no officer dared to openly criticize or confront him. The specter of Big Tim cast a shadow across every precinct.