Jackson, Calvin, 1948- , U.S. A Manhattan police detective admitted that “depersonalization” and a “lack of interest” on the part of the homicide squad was partly to blame for the murder of nine elderly women at the seedy Park Plaza Hotel between April 1973 and September 1974. Even after the first victims had been found dead in their shabby, ill-equipped apartments, “no immediate police action was taken on any of them.” The shoddy detective work and casual disregard for the lives of these elderly women led to a general shakeup in the New York City Police Department’s Fourth Homicide Zone. Lieutenant James Gallagher, who failed to consider that the murders might have been the work of one man, was transferred to internal affairs. The long overdue reorganization had unfortunately come at the expense of at least nine lives.

The Park Plaza was located on West 77th Street in Manhattan. Despite the rather elegant name, most of its elderly residents lived barely above the poverty level in tiny, cramped rooms. The corridors were poorly lit and many residents dead bolted their doors at night to keep out muggers, thieves, and rapists. The eleven-story hotel was a seedbed of crime on the West Side. Begmning on Apr. 10, 1973, when 39-year-old Theresa Jordan was found suffocated in her apartment, the Park Plaza took on an even more sinister character. A homicidal maniac was loose in the building, but the police were hard pressed to provide answers to the anxious residents.

The killer struck again on July 19. Kate Lewisohn, sixty-five, was strangled to death and her skull crushed by the unknown assailant. For the next few months no more bodies were found, until on Apr. 24, 1974, 60-year-old Mabel Hartmeyer was found dead in her room. The Medical Examiner’s Office attributed her death to “occlusive coronary arteriosclerosis.” Although the police accepted this verdict without question, it was subsequently shown that the woman had been strangled and raped. Four days later 79-year-old Yetta Vishnefsky, a retired sewing machine operator, was stabbed to death with a butcher knife. She had been bound, gagged, and raped before she was murdered. A television set, some jewelry, and a few items of clothing had been stolen. Following the Vishnefsky murder the body count rose steadily. Forty-seven-year-old Winifred Miller, an accomplished pianist and singer, was the victim on June 8; followed by Blanche Vincent, seventy-one, on June 19; Martha Carpenter, sixty-nine on July 1; and 64-year-old sculptor Eleanor Platt, on Aug. 30. At first the medical examiner ruled out homicide in the cases of Vincent and Platt. Their deaths were blamed on chronic alcoholism and heart failure. Detectives from the Fourth Homicide Zone classified their files as “pending,” an acknowledgment that murder could not be ruled out entirely.

On the morning of Sept. 12, 1974, the police received a frantic call from Dorothy May, the maid of Mrs. Pauline Spanierman, a 59-year-old widow living in an apartment building adjoining the Plaza. She said that her employer had been murdered. The medical examiner affixed the time of death at shortly after 3 a.m. It was the first time the killer had selected a victim outside the residential hotel. Police detectives questioned the residents of Spanierman’s building and learned that a suspicious-looking man had crawled down a fire escape clutching a small TV set under his arm. Later that afternoon police detectives arrested 26-year-old Calvin Jackson at the intersection of 77th Street and Columbus Avenue and charged him with murder and possession of stolen property. Jackson was a former inmate at the Elmira, N.Y., State Correctional Facility, with a long record of robbery and drug convictions. He had been living at the Park Plaza Hotel since 1972 and had been arrested on Nov. 7, 1973, for pilfering a television and stereo set from one of his neighbors—a crime for which he plea-bargained his way to a thirty-day sentence rather than the fifteen years it normally carried. Jackson returned to the Plaza where he earned his living working as a porter.

Born in Buffalo, Jackson’s career up to the time he moved into the Park Plaza with his girlfriend Valerie Coleman was a road map of crime. He had drifted aimlessly from one flophouse to another, committing petty robberies and dealing drugs. He was described by Coleman as a soft-spoken, “caring” individual. “Jack was the kind of person if you needed something and he had it, he’d give it to you,” she said. Jackson was taken to the Manhattan Criminal Court for arraignment the day after his arrest. Under direct questioning from Assistant District Attorney Kenneth D. Klein and a battery of detectives, Jackson confessed in hushed tones to killing Spanierman and the other elderly women. He was kept under close watch at the Manhattan House of Detention for Men to prevent a suicide attempt.

On Nov. 3, 1974, State Supreme Court justice Joseph A. Martinis ruled that Jackson was mentally competent to stand trial, against the strongly vociferous objections of defense attorneys Donald Tucker and Robert Blossner. “If Calvin Jackson is not legally insane, who is legally insane? He raped women, some in their seventies and eighties. He raped some of them after death. Is this a legally sane man?” Tucker wanted to know. “He went to the refrigerator in nearly every apartment. He prepared a meal and ate it as he watched the body. Sometimes he stayed for an hour. Is this a legally sane man?” The jury agreed with the judge, returning a verdict of Guilty against Jackson on nine counts of murder on May 25, 1976. Jackson’s five-hour taped confession that had been played inside the jury room was a major factor in their decision. Justice Aloysius J. Melia of the State Supreme Court sentenced the defendant to two life terms for each victim. Jackson will not be eligible for parole until the year 2030.

Jackson, Louie (AKA: Louise; Louisa Gomersal; Louie Calvert), b.1897, Brit. When Arthur “Arty” Calvert hired Louie Jackson as housekeeper for his Hunslet, England, home in 1925, he knew only that she was a widow with two small children. As the weeks went by, the watchman grew intimate with Jackson. Soon she informed Calvert she was pregnant with his child and they were married. With the baby due soon, Louie told her husband that she was going to stay with her sister until the baby was born. Three weeks later she returned with a baby girl. A suitcase arrived at the house, which Louie Calvert said contained baby clothes. Later that day, the police came to the house and arrested her.

Louie was better known to English officials as Louisa Gomersal, a thief and prostitute, and now she was wanted on charges of murder. Gomersal had lied to Calvert about the pregnancy and left to find a baby. She took a room in a boarding house run by Lily Waterhouse, and found a 17-year-old girl willing to give up her baby. While she waited for the baby to be born, Gomersal stole from Waterhouse. The 40-year-old spiritualist, who had already confronted the hot-tempered Louisa, went to the police with her complaint. Waterhouse was found dead the next day. A letter in the rooming house led authorities to Calvert’s home. Police found cutlery in the bag which supposedly contained baby clothes. Gomersal was found Guilty of murder and her plea of pregnancy was disregarded. Before her execution, Louie Calvert admitted also killing John Frobisher and dumping his body in a canal in 1922.

Jackson, R.E., prom. 1962, and Jackson, Clemmie, 1943- , U.S. At sixty-one years of age, Samuel L. Resnick suffered from incurable cancer, heart trouble, and diabetes. The jeweler from Albany, N.Y., had retired to Phoenix, Ariz., and now he wanted to die there. He scanned the job-wanted ads in the newspapers each day for someone to end his pain. At least five men turned Resnick down when he asked them to kill him. Resnick finally contacted Clemmie Jackson, a Texas farmhand who had arrived in Arizona with dreams of owning a car wash.

Jackson first refused to have any part of the murder plot, but when Resnick promised the 19-year-old enough money to open his own business, Jackson agreed. Jackson recruited his brother, R.E. Jackson, and three other youths to help. Resnick promised the young men cash and jewelry and drove with four of them into the desert just north of Phoenix. By this time, Clemmie Jackson had backed out. When the youths tried to strangle Resnick to death, the rope broke. Resnick then assisted the amateur murderers in completing their task. The killers ended up with $3,000 worth of jewelry, but no cash. Three days later the body was discovered and the youths had left so many clues that they were quickly apprehended. The four conspirators were all tried, convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. Clemmie Jackson was acquitted.

Jacobson, Howard (AKA: Buddy), 1930-89, U.S. At the age of seventeen, Melanie Cain arrived in New York in 1972 with dreams of becoming an actress. Within months, the Naperville, Ill., native signed with one of New York’s top modeling agencies and began a relationship with her landlord, Howard “Buddy” Jacobson. Formerly one of the country’s top trainers of thoroughbred race horses, following a dispute with the New York Racing Association Jacobson was forced to turn to real estate, a field in which he became successful. When Cain was fired from Eileen Ford’s modeling agency, she and Jacobson started their own agency. Christened My Fair Lady after Cain’s favorite musical, the agency prospered with Melanie as its star attraction.

Jacobson, who had told Cain he was twenty-nine, was really forty-two. The two men he introduced as his brothers were really the divorced man’s sons. For nearly five years, Cain tolerated rumors that her boyfriend slept with a number of women at the agency. In 1978, Cain met handsome young restaurateur Jack Tupper while jogging, and within weeks she left Jacobson and moved in with her new boyfriend, who also lived in Jacobson’s building.

Jacobson harassed Cain and Tupper with phone calls and noise. He turned off the hot water in their apartment and offered the 34-year-old Tupper and some of his friends $100,000 if Cain would return to him. On the morning of Aug. 6, 1978, Cain left the apartment building at 155 E. 84th St. to sign the lease for a new apartment, so she and Tupper could escape their tormentor.

When Cain returned early that afternoon, Tupper was not home and she went to Jacobson’s apartment. No one answered the door and Cain returned to her apartment to wait for Jack. Upon hearing noise in the hallway, she peeked out to see Jacobson and one of his sons tearing up the rug in the hallway. After the men left, Cain stepped out in the hall and discovered reddish, moist stains on the padding which had been covered by white paint. She also found a tuft of hair, a smeared palm print on the elevator, and other spots in the hall that had been freshly painted. Cain returned to Jacobson’s apartment and asked him where Tupper was, but he said he hadn’t seen him all morning. Cain called police.

The next day, Estella Carattini identified a car belonging to Jacobson. She said that Jacobson and one of his employees, Salvatore Prainito, dragged a crate from the trunk of the 1974 Cadillac into a vacant lot, set fire to the crate and then fled the scene. When police found Jack Tupper’s body, it was barely identifiable. He had been beaten, stabbed repeatedly, and then set afire. Police arrested Jacobson and charged him with murder. In a 1980 trial, Jacobson was found Guilty of second-degree murder. But only three days before he was scheduled to receive his prison sentence, he escaped from jail on May 31 by calling in a debt. An old friend, Anthony DeRosa, posing as a lawyer, brought a razor and a change of clothes into the Brooklyn House of Detention and Jacobson walked out minus his bushy moustache. Jacobson’s latest girlfriend, Audrey Barrett, was waiting in the parking lot and the two fled the state. The court sentenced Jacobson in absentia to twenty-five years in prison.

On June 29, Barrett surrendered to authorities and was charged with criminal facilitation, first-degree escape, and possession of legal stationery. Ten days later, in the Los Angeles suburb of Manhattan Beach, local police arrested Jacobson. He was on a restaurant pay-phone calling the district attorney’s office in Brooklyn to make arrangements to turn himself in. Jacobson died of cancer in Buffalo, N.Y., in May 1989.

Jacoby, Henry Julius (AKA: Harry), 1904-22, Brit. Henry Jacoby, eighteen, who worked at Spencer’s Hotel on Portman Street, London, had planned for weeks to rob one of the wealthy guests at the hotel. His opportunity came on the night of Mar. 14, 1922, when he crept into the room of Lady Alice White, believing that the 60-year-old dowager was not in. In precarious health since the previous December, she was asleep in her room.

Alice White, the widow of Sir Edward White, a former London County Council chairman, was startled by Jacoby’s invasion, and he struck her with a hammer. The elderly woman died the next morning. Jacoby was arrested and charged with murder a few days later. He casually remarked to a police officer, “Isn’t it funny how much strength a man’s got?” referring to the brutal blow he had given White.

The trial began at the Old Bailey on Apr. 28, 1922. Jacoby said he had “heard voices” and had gone to the guests’ rooms to investigate. The door of room Number 14, belonging to White, stood open. “I thought I heard murmurings inside,” Jacoby said, “I rushed in and seeing a form, lashed out. I did not know it was Lady White.” Jacoby was found Guilty of murder, but the jury recommended mercy, given his age. The plea was rejected by the home secretary and Jacoby was hanged at Pentonville Prison on June 5 over a storm of protest. Ronald True, a member of a titled family, had recently murdered a London prostitute, but had been reprieved on the grounds of insanity.

Jagusch, August, prom. 1951, U.S. At twelve, August Jagusch’s father stabbed him in the arm with a bread knife when Jagusch refused to eat unpeeled potatoes. He then ran away from home, and when he was returned home by police his father suggested he should be locked up. For sixteen months, Jagusch endured a series of sexual liaisons at Children’s Village in Dobbs Ferry, N.Y. He was constantly assaulted by male counselors, and slept with several female teachers and fellow inmates, all before turning fifteen.

Upon his release from the children’s home, Jagusch continued to be sexually promiscuous. Although he later married and had a daughter, the relationship ended in divorce. In June 1951, Jagusch strangled to death a young Staten Island striptease dancer named Mildred Fogarty. His ex-wife turned Jagusch in to the police when he contacted her after the murder. He told police that Fogarty had enraged him during a sex act and that he went berserk and strangled the woman. Jagusch was found Guilty of second-degree murder and sentenced to twenty years in prison. He was released on Aug. 23, 1967, after serving sixteen and a half years in Auburn State Prison.

Jahnke, Richard J., 1967- , U.S. The beatings began at age two for Richard J. Jahnke. His father, Richard C. Jahnke, also beat young Richard’s sister, Deborah Jahnke, and his mother, Maria Jahnke. The IRS agent and his family lived in Cheyenne, Wyo. He collected guns, had few friends and rarely socialized with neighbors or co-workers. After years of unreported abuse, 16-year-old Richard confided in Major Robert Vegvary, his ROTC instructor at Central High School. In May 1982, Vegvary accompanied Jahnke to the sheriffs office to file a complaint. A perfunctory visit to the Jahnke household a few weeks later only enraged the father.

Richard C. Jahnke told his son that he would never forgive him for going to the authorities. On Nov. 16, Richard fought with his mother over cleaning the basement. Later, as the parents left to celebrate their twentieth anniversary, Jahnke told his son he did not want to see him there when he returned.

During the hour-and-a-half the couple were gone, Richard and his sister loaded a number of guns and placed them around the house. Deborah was stationed in the living room with a rifle, and her brother hid in the garage with a shotgun. The parents’ car pulled in the driveway, and the elder Jahnke turned off the engine and got out of the car. As he approached the garage door entrance to the house, two shotgun blasts hit the 38-year-old man. The younger Jahnke fired four more times into his father who lay on the garage floor. Richard C. Jahnke died within minutes from chest wounds. His son was arrested and charged with murder.

In February 1983, a jury deliberated seven hours before declaring Jahnke Guilty of voluntary manslaughter in the death of his father. He was also found Not Guilty on one count of conspiracy. Although his murder conviction was upheld by the Wyoming Supreme Court, Jahnke’s five- to fifteen-year sentence was reduced to three years by Governor Ed Herschler.

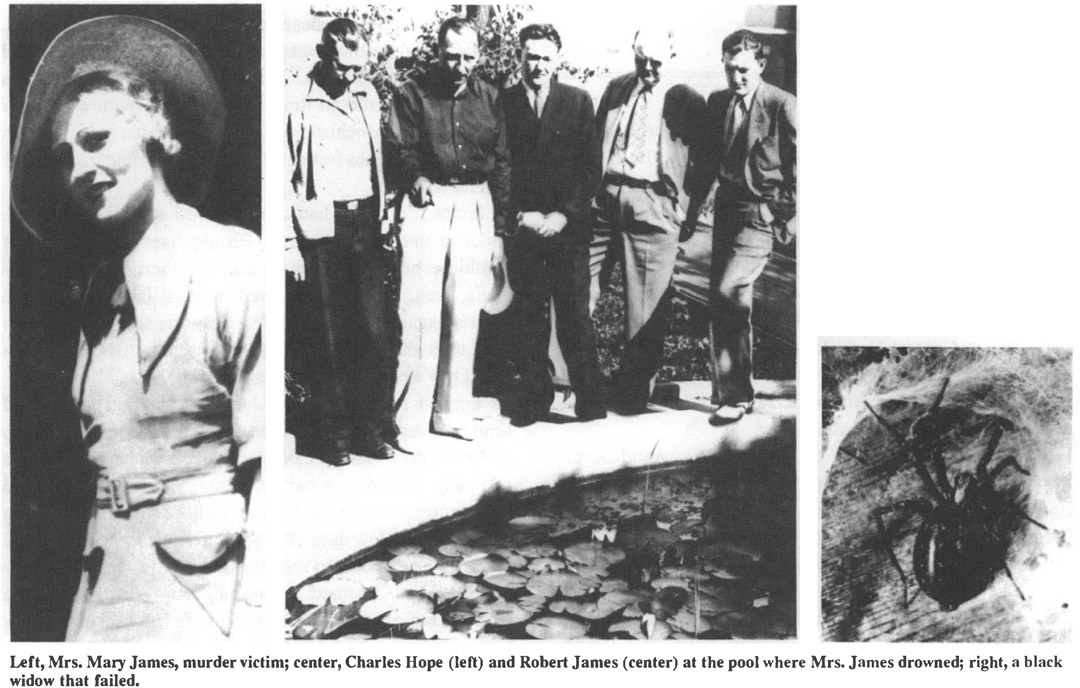

James, Robert (Raymond Lisemba), 1895-1942, U.S. Born Raymond Lisemba in rural Alabama in 1895, Robert James had done the back-breaking work of a cotton baler until he inherited $2,000 from each of two uncles who had named him beneficiary of their insurance policies. Receiving such a windfall without expending any effort made a lasting impression on the young man. He took his inheritance and traveled to Birmingham, Ala., where he attended a barbers’ college and changed his name to James. It was also in Birmingham, in 1921, that he met and married Maud Duncan. This first marriage ended when James’s wife could no longer tolerate his requirements of her for sadomasochistic sex. In the divorce suit, Duncan claimed that James frequently stuck hot curling irons under her nails.

James reportedly had also fathered several illegitimate children during his time in Birmingham and decided it would be healthier to move on. He then moved to Emporia, Kan., where he opened a small barber shop and married again. He suddenly left Emporia and his wife when the father of a girl he had gotten pregnant threatened his life. Only weeks after arriving in Fargo, N.D., his next stop, he opened another barber shop and married for a third time to Winona Wallace. The newlyweds’ honeymoon trip to Colorado’s Pike’s Peak was marred when Winona was seriously injured in a car accident. When she recovered sufficiently to be released, James took her to a remote cabin in Canada. A few days after their arrival, James appeared at the police station to report that his wife, dizzy from the accident, had drowned in the bathtub. Shortly after the funeral, James collected $14,000 in life insurance—a policy he had taken out on her life a day before the wedding.

In Alabama, in 1934, James met a local girl, Helen Smith. The two were married and moved to Los Angeles. Helen Smith later told authorities that James was sexually impotent unless she whipped hini. This fourth wife became suspicious when he told her he wanted her to have a medical examination for a life insurance policy. She refused saying that “people who have it (insurance) always die of something strange.” James resented her obstinacy and the two were soon divorced. Next, James took out a $10,000 life insurance policy on a nephew, Cornelius Wright, then a sailor stationed at San Diego. Wright had a long history of being accident-prone—he had been hit several times by cars; some scaffolding had once collapsed on him; he had been knocked unconscious at a baseball game. James, playing the magnanimous uncle, loaned him his car to use while on leave and told him to go off and have a good time. Three days later, Wright drove the car off a cliff near Santa Rosa and died. Only later did the mechanic who towed the wrecked car away tell police that something was wrong with the steering wheel.

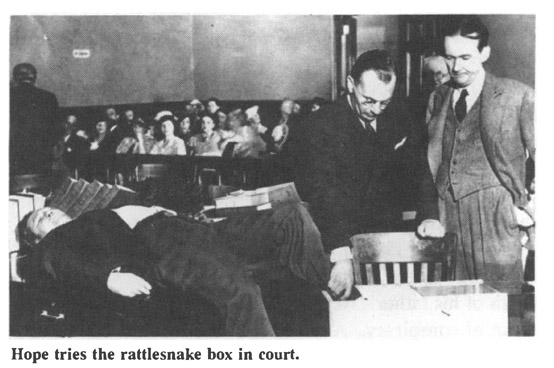

With the money he collected on his nephew’s death, James opened a posh barber shop in Los Angeles and he began an affair with his manicurist, 25-year-old Mary Bush. When Bush became pregnant and insisted that James marry her, he did so. Not long after their marriage, however, James again took out another insurance policy. Then he persuaded one of his employees to find a couple of poisonous snakes, explaining that he had a friend whose wife was bothering him and he wanted the snakes to “take care of her.” In July 1935, the employee, Charlie Hope, went to “Snake Joe” Houtenbrink, a reptile collector, and procured two Crotalus Atrox rattlers. James then brought Hope in on his plot to kill his wife and promised him part of the insurance money.

After working out the details, James took Hope home with him for dinner one evening, introducing him as a doctor. After Hope had been in their home for a brief period, he told the pregnant Mrs. James that she did not look well and probably should not go through with her pregnancy. The naive woman agreed to let this “eminent physician” perform an abortion on her that very night. In lieu of anesthetic, James encouraged her to drink whiskey until she passed out. Once she was incoherent, he brought the snakes into the house in a specially designed box constructed so that he could insert her leg into it without letting the snakes escape. He left her for several hours with her leg in the box, and she was bitten repeatedly. She did not die, however. When she revived and complained of terrible pain in her leg, James assured her it was nothing important. The leg, however, swelled to twice its normal size and became increasingly painful. Early in the morning, James suggested that she take a bath to soothe the pain. He ran the water into the bathtub for her and stood by to help her into the tub. As she got into the tub, James pushed her down, pulling her legs high enough so that her head was submerged and held her in this fashion until she drowned.

After dressing her, he and Hope carried her body to the yard, where they placed it face down in a small lily pond in such a way as to make it appear that she had become dizzy and collapsed, and accidentally drowned. After going over the alibi with Hope, James went on to work. He worked through the day as though nothing at all was wrong, and that evening returned home with two friends whom he had invited to dinner, ostensibly after clearing the impromptu dinner party with his wife. As planned, the three “discovered” his wife’s body in the pond. The death was classified as accidental.

Three months later, however, a Los Angeles captain of detectives, Jack Southard, saw a report that James had been arrested for propositioning a woman and thought it peculiar that a man so recently widowed should be apprehended for such a crime.

Southard learned from neighbors that a green Buick sedan had been seen outside the James home and that Charles Hope had been phoning James constantly. Southard also discovered that Hope owned a green Buick sedan, so he searched Hope’s apartment. There he found a receipt for two rattlesnakes. Southard collected enough evidence against Charlie Hope to arrest him on suspicion of murder. Once arrested, Hope confessed, implicating James. James was arrested in May 1936 and after a quick trial, was sentenced to death. Hope received a life sentence. James remained in the Los Angeles County Jail for the next four years while appealing his case. In 1940, he was finally moved to San Quentin. As it became evident that commutation of his sentence was unlikely, James fought to die in the gas chamber instead of by hanging because the law changing the manner of execution was enacted after his sentencing. On May 1, 1942, Robert James was hanged at San Quentin, the last man to be hanged in California.

Jeffs, Doreen, d.1965, Brit. In November 1960, in Eastborne, England, Doreen Jeffs killed her baby daughter and then fabricated a kidnapping. When the corpse was found, Jeffs’s story was challenged and she soon confessed and pleaded guilty to murder. Her defense attorney successfully presented a case for duress based on the fact that the child, Linda Jeffs, was a month premature. Contending that Jeffs was “a woman who committed an offense while under the stress of childbirth,” the lawyer got Jeffs sent to a mental institution. She was later put on probation. Jeffs attempted suicide by taking gas, but was interrupted. Over four years later, in January 1965, she neatly folded her clothes by a cliff overlooking the English Channel near Beachy Head and dove into the ocean. Her body surfaced near the shore several days later.

Jenkin, William Thomas Francis, 1934- , Brit. On Apr. 13, 1959, the body of 12-year-old Janice Anne Holmes was found in Binbrook, Lincolnshire, England. Four days later, a 24-year-old truck driver, William Thomas Francis Jenkin, of Hall Farm Estate, was arrested for the murder. The prosecution charged that Jenkin lured the little girl into the woods, where he assaulted and strangled her. He denied the charge, and his wife claimed that he had spent the evening searching for the missing child. The first trial ended with a hung jury, but at the retrial on July 16, 1959, Jenkin was found Guilty of the murder and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Jenkins, Allison, 1960- , U.S. For Chicago police officers Jay Brunkella and Fred Hattenberger, Sept. 22, 1986, was a routine day in the war on drugs. The officers, part of an eight-man unit assigned to patrol the neighborhoods north of Howard Street, near Evanston, were staked out on the third floor of an aging elementary school. The officers observed small-time dope peddlers in operation, and radioed the license plate numbers of buyers to an arrest car waiting a few blocks away. Allison Jenkins was a familiar face to Brunkella. The 28-year-old native of Belize had been arrested on a number of minor charges, most recently for selling cocaine to an undercover police officer. When the policemen observed what they thought was a drug transaction, they left the building to arrest Jenkins.

During the attempted arrest of the pusher, Hatten-berger’s gun discharged and hit Brunkella in the chest. There were no ambulances immediately available to transport Brunkella to the hospital, so his fellow officers placed him in the back of the squad car. After eleven days in intensive care, Brunkella died on Oct. 4, 1986. Jenkins, who had originally been charged with selling marijuana and aggravated battery, was now charged with the murder of a police officer. In January 1987, a jury convicted Jenkins of delivering a controlled substance, and Criminal Court Judge Joseph Urso sentenced him to six years in prison.

Urso also presided over Jenkins’ murder trial, which began in September. The defendant’s lawyer, Craig Katz, argued that his client was framed by a trigger-happy cop who had taken unnecessary risks with his weapon. The prosecution contended that Jenkins, on parole, had tried to flee from the officers. State’s Attorney Dennis Dernbach argued that Jenkins and Hattenberger struggled, and that the defendant caused the policeman’s gun to fire. A jury found Jenkins Guilty of murder, but within days one juror called the judge and said that she had been pressured into rendering a Guilty verdict. Katz then petitioned the court to set aside the jury’s verdict because he had new evidence in the case.

Police officer James Crooks then testified that he had seen Hattenberger use unnecessary force on one occasion. It was also revealed that Hattenberger had once before wounded a fellow officer in the line of duty. On Nov. 13, 1988, Urso denied the motion for a new trial. Jenkins was sentenced to twenty years in prison for murder.

Jennings, James Brandon (AKA: Kid Carter), b.1880, U.S. On New Year’s Day 1913, James Brandon Jennings, better known to his boxing fans as “Kid Carter,” shot and killed Bill MacPherson after a fight began in Garrity and Prendergast’s Saloon in Boston’s South End. Although there were many witnesses to the crime, no one was able to give a reason for the slaying. Jennings was taken into custody immediately and tried for the murder beginning on Mar. 24, 1913. On Mar. 28, the jury returned a verdict of Guilty of murder in the second degree. On Apr. 18, 1913, just after his sentencing to life in prison, Jennings blurted out to a crowded courtroom that he had also murdered his girlfriend, Mildred Donovan, as well as “many others.” No further legal action was taken against “Kid Carter,” although he was found unfit to serve time in the state penitentiary and was committed instead to the Bridgewater State Hospital for the criminally insane.

Jesse, Frederick William Maximilian, 1897-1923, Brit. Frederick William Maximilian Jesse strangled and dismembered his aunt, Mabel Jennings Edmunds on July 21, 1923. A week later when Jesse confessed, police found Mrs. Edmunds’ legs on the table on the top floor, and her trunk on the bed wrapped and tied with rope. According to Jesse, he and his aunt quarrelled and when he went to his room to get away from her, she followed and continued to hit him and throw a liquid on him. By Jesse’s account the next thing he remembered was finding his hands around his dead aunt’s neck. He told police that he had intended to dispose of the body but became afraid. Jesse was tried at the Old Bailey in September 1923. He was found Guilty, sentenced, and, on Nov. 1, hanged.

Jobin, Marie, prom. 1920, Fr. In 1920, Gaston and Marie Jobin were married and living in Paris. Marie consorted with other men and Gaston led a life of petty thievery.

On Mar. 23, 1920, Gaston Jobin was seen for the last time. Marie claimed that he had fled to Spain to avoid military conscription. On Apr. 8, 1920, however, a man’s torso, minus head and limbs, was dragged from the Seine. Then, eighteen months later, a postal official examining a stack of undeliverable mail discovered an underlined paragraph about the body’s discovery in a letter addressed to Paul Jobin, Gaston’s brother. The letter had been sent by their sister in Switzerland, who was convinced that their brother was murdered.

The police again visited Marie Jobin, who was living in a Toul hotel with a man named Burger. Although Marie repeated her original story, she asked her lawyer a curious question: Legally, when would she be free to marry again? This querry from a woman who claimed her husband was alive and well. Mr. Warrain, the interrogator, kept at them until the two confessed to having murdered Gaston Jobin on Mar. 23, 1920. Burger was sentenced to death, and Marie Jobin to hard labor for life. She died a few years later.

Johnson, Milton, 1950- , and Lego, Donald, 1933- , U.S. In the summer of 1983, five multiple murders in Will County, Ill., resulted in seventeen deaths. A small, citizen-financed crime fighting organization, Crime Stoppers of Will County, helped apprehend two suspects, Milton Johnson and Donald Lego. Lego was convicted in the stabbing and bludgeoning murder of an 82-year-old widow, the last of the seventeen victims, on Mar, 16, 1984. On the same day, Johnson pleaded not guilty to charges of the murder of an 18-year-old man and the rape of his 17-year-old female companion. In August, he was convicted of the attacks and when given the choice of being sentenced by Judge Michael Orenic, or by the jury, he opted for the judge. On Sept. 19, 1984, Judge Orenic, who was on record as opposing the death penalty, sentenced Milton Johnson to die by lethal injection. On Jan. 28, 1986, Johnson was convicted of four more deaths in the same murder spree.

Johnson, Robert, 1924- , U.S. Robert Johnson, of Wilmington, N.C., clubbed four of his children to death within twenty-four hours of his wife’s abandoning the family in September 1971. A fifth child survived the brutal beatings. His wife Bonnie Louise Johnson had recently threatened to leave him, saying that she felt trapped in her marriage and that she had too many children to care for.

Before clubbing his children, Johnson had contacted a Wilmington television station, hoping to broadcast an appeal for his wife’s return. Two hours later, he contacted police and led them to the murder site. He was charged with the murders of the four children and the attempted murder of one daughter, the only survivor. He was sent to Cherry Hospital in Goldsboro, N.C., for a sixty-day mental observation period, and later to prison at Southport, N.C.

Johnson had a troubled past. He received a dishonorable discharge during WWII, after serving time for desertion. He also had a civilian record for forgery and the interstate transportation of a stolen airplane. But he had stayed clear of trouble for twelve years until September 1971.

Johnson, Terry Lee, 1949- , U.S. Johnson, an ex-Marine from rural Alabama, turned to a life of crime after being released from the service. Dealing in narcotics replaced the occupations of carpet installing, landscaping, logging, welding, and construction work. Through his Marine experience, Johnson was adept at living in the wilderness and with handling a wide array of firearms. He was charged with murder and found Guilty of killing an unarmed farmer.

Johnson subsequently escaped from prison and was last seen in Alabama, carrying a high-powered rifle. At this time he is still a fugitive.

Johnson, Vateness, 1951- , and Johnson, Frank, c.1947- , U.S. Vateness Johnson and her husband, Frank Johnson, were convicted of the Mar. 12, 1985, murder of 5-year-old Judy Moses, who was in their foster care. The child, along with her three-year-old sister, were put in the Johnson’s care after the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services deemed their real father incapable of properly caring for them. The children were repeatedly beaten and on the last day of her life, 5-year-old Judy was tied to a chair in the Johnson’s unheated garage.

In 1985, Vateness Johnson was convicted and sentenced to sixty years in prison while her husband was sentenced to twenty-two years. The Illinois Court of Appeals ordered a new trial, saying that the couple should have been tried separately. Frank Johnson denied the actual beatings, and was allowed to plea-bargain a lesser sentence of involuntary manslaughter. His sentence was reduced to eight years. On Nov. 24, 1988, a Will County, Ill., jury was shown pictures of the brutally-beaten children, listened to a medical examiner’s report, and upheld the earlier conviction of Vateness Johnson.

Johnston, Bruce, Sr., 1939- , and Johnston, David, 1948- , and Johnston, Norman, 1951- , U.S. In two separate trials in eastern Pennsylvania in 1978, the Johnston brothers were convicted of murdering six people, including a family member, and of attempting to kill one other person.

Two generations of the Johnston clan formed a theft ring that was accused of stealing well over $1 million in cars, jewelry, and farm equipment. When family member Bruce Johnston, Jr., suspected his father of having raped his friend Robin Miller, however, he went to authorities, unaware that his betrayal would result in five murders.

On July 17, 1977, Bruce Johnston, Sr., murdered Gary Wayne Crouch, thirty-one. Then on Aug. 16, 1978, David and Norman Johnston murdered James Johnston, eighteen, Bruce, Jr.,’s half-brother, Wayne Sampson, eighteen, and Duane Lincoln, seventeen, near Chadds Ford, Pa. On Aug. 20, Wayne’s brother, James Sampson, twenty-four, became the fourth victim. And on Aug. 30, Bruce, Jr., and his fiancee Robin Miller, fifteen, were ambushed; Miller died.

On Mar. 18, 1980, in Edensberg, Pa., David and Norman Johnston were convicted of four murders and were each sentenced to four life sentences. On Nov. 15, 1980, in the West Chester courtroom of Judge Leonard Sugarman, Bruce Johnston, Sr., after testimony by 126 witnesses, including his son, was found Guilty of all six murders and sentenced to life in prison.

Jon, Gee, d.1924, U.S. After he was found Guilty of murder and sentenced to death, Gee Jon was held in the Carson City (Nev.) Courthouse and became the center of a controversy. In an effort to clean up Nevada’s image as a comparatively lawless frontier state, Governor Emmet Boyle signed a new capital punishment bill from the state legislature in 1921. There had been debate over whether to abolish the death penalty entirely or to substitute some improved form of execution. The bill rejected electrocution, and instead mandated introducing a lethal gas into the convict’s cell while he slept. When it proved too complicated for the public executioner to introduce lethal gas into an ordinary cell, Jon was temporarily saved from execution. When the Nevada Supreme Court declared the gas execution bill valid and ordered the sentence to be carried out, an improvised structure was constructed and made air tight. On Feb. 8, 1924, Jon died from inhaling cyanide gas.

Jones, Genene, 1951- , U.S. In September 1982, a 15-month-old baby girl mysteriously died in Kerrville, Texas, after a routine examination by a local pediatrician. A powerful muscle relaxer, Anectine, which had not been prescribed, was later found to be the cause of death. Six other children at the clinic had suffered similar attacks in a six-week period, with nurse Genene Jones always nearby. Aiding healthy babies did not offer a great enough challenge, so Jones created “life-and-death” situations. She became euphoric when administering CPR and other life-saving techniques to her victims.

A subsequent investigation in San Antonio uncovered more horrors. When Jones worked the night shift at a local hospital, more than twelve inexplicable deaths had occurred, earning her the name of the “Death Nurse.” On Feb. 15, 1984, she was convicted of murder and sentenced to ninety-nine years in prison.

Jones, James Warren (Jim), 1931-78, Guyana. Boyhood friends of the Reverend James Jones would recall the times when he held mock funeral services for dead animals in the Indiana town of Lynn, whose cottage industry was casketmaking. “Some of the neighbors would have cats missing and we always thought he was using them for sacrifices,” recalled Tootie Morton. Jones, whose father was a drunken Klansman unable to hold a job, became obsessed with religion. At fourteen, the Bible-toting boy delivered his first sermon. In 1949, Jones married Marceline Baldwin, his high school sweetheart.

After dropping out of Indiana University, the couple moved to Indianapolis where they started a Methodist Mission, but the church fathers found his religious pretensions objectionable and he was expelled in 1954. Jones then raised money by importing monkeys and selling them for $29 each. He accumulated $50,000, which was used to purchase a rundown synagogue in a black neighborhood of Indianapolis. During this time he and his wife adopted eight Korean and black children.

The mayor of Indianapolis, impressed with Jones’ community work in the impoverished neighborhoods of the city, appointed him director of the Human Rights Commission. But when Jones found Indianapolis too provincial in its racial attitudes, he moved to Belo Horizonte, Braz., after reading that this was the safest spot in the world to survive a nuclear holocaust. The family later relocated to Rio de Janeiro where Jones taught in an American school. Hearing that the People’s Temple in Indianapolis, which he had founded in 1957, was in the midst of a leadership crisis, Jones returned home. In 1964, he affiliated his group with the Disciples of Christ and was ordained a minister.

Influenced by the Reverend Ross Case, and half-believing that the world was about to end, Jones led a migration of 100 followers from Indiana to Redwood Valley, in Mendocino County, Calif. The minister purchased a synagogue in the deteriorating Fillmore district of San Francisco. He provided a day-care center and food kitchens for the black inner-city residents, who accounted for 80 percent of the congregation of the People’s Temple and won the enthusiastic support of politicians. Governor Jerry Brown was a visitor to the People’s Temple. Mayor George Moscone appointed Jones to serve on the city’s housing authority as a reward for his political support in the 1975 election. After hearing of the Jonestown horror, Moscone would say, “I proceeded to vomit and cry.”

Money began to roll in. Jim Jones purchased Greyhound buses and began traveling around the country accompanied by bodyguards and press aides. At the same time he preached sexual abstinence to his congregation, he surrounded himself with female followers. In 1974, he purchased 27,000 acres of rain forest in Guyana on the northern coast of South America, which he hoped to turn into a socialist utopia for himself and his followers. Despite warm endorsements from top Democratic leaders like Henry “Scoop” Jackson, Walter Mondale, and Jimmy Carter, whom Jones supported for president in 1976, he became obsessed with the notion of mass suicide as a way of escaping governmental persecution, a fascination with suicide dating to 1953 when Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were executed in the U.S. as spies. By 1976, Jones was indoctrinating his followers in the concept of a “White Night,” a mass suicide ritual that was being “rehearsed” at his People’s Temple.

The first clue the public had about Jones’ hidden agenda and the secret cult activities occurred at an anti-suicide rally held at the Golden Gate Bridge on Memorial Day 1977. Speaking before hundreds of spectators, Jones called for the construction of an anti-suicide barrier to be constructed on the bridge. Dr. Richard Seiden, professor of behavioral science at the University of California, later recalled how the direction of Jones’s speech changed. His condemnation of suicide became almost a blanket endorsement for it. “He saw himself as the victim, persecuted and attacked, and from there proceeded to the concept of suicide as an appropriate response. We were not aware of the nuances and implications,” Dr. Seiden said.

Membership in the People’s Temple swelled to nearly 20,000, and his services became increasingly bizarre. He claimed to have the power of faith healing, and would draw out the “cancer” from the sufferer during ceremonies—the cancer actually a bloody chicken gizzard. No longer content to be the reincarnation of Jesus, Jones began calling himself God. With the help of local authorities in Guyana and private contributions from his followers, he began clearing large sections of jungle in 1977. That year, the religious colony of Jonestown was founded and about 1,000 members made their exodus from San Francisco to the jungle retreat.

Jones enforced his will through physical and mental coercion. The San Francisco Examiner reported in August 1977 that members were publicly flogged for minor infractions like smoking and falling asleep during religious sermons. Electrodes were attached to children who were ordered to smile at the mention of the leader’s name. These reports began filtering back to California congressman Leo Ryan, fifty-three, who pressured the U.S. State Department to investigate. A delegation from the U.S. embassy in Georgetown interviewed seventy-five members of the cult, but none indicated a desire to leave. Ryan was not convinced. His friend, Robert Houston of the Associated Press, had lost a son to the cult. The young man had been murdered in San Francisco after attempting to quit the People’s Temple. Ryan embarked on a fact-finding mission on Nov. 14, 1978, accompanied by eight journalists and several relatives of Jonestown cultists.

They were greeted by the congenial Jones, who led a guided tour through the compound, proudly showing off the spacious library, hospital, and living quarters. That night Congressman Ryan and his party were entertained at the pavilion. Even Ryan was impressed. He arose from his chair and said, “From what I have seen, there are a lot of people here who think this is the best thing that has happened in their whole lives.” Jones led the thunderous applause.

The next day NBC reporter Don Harris asked Jones about his military arsenal and if it were true that the compound was under heavy guard. Jones exploded in rage. “A bold-faced lie!” he screamed. One of the cultists slipped a note to Ryan which read “Four of us want to leave.” There were other similar requests. While Ryan spoke with Jones about moving these people out, a cultist named Don Sly attacked him with a knife but was subdued by attorney Charles Garry. Ryan and his entourage departed for the airfield at Port Kaituma and an awaiting Cessna. As they deliberated about the best way to squeeze the extra passengers into the tiny craft, a flatbed truck rumbled by. Three armed men standing in the trailer suddenly opened fire. From inside the plane, Larry Layton produced a gun and began shooting. The crossfire left five persons dead—Congressman Ryan, photographer Greg Robinson, NBC cameraman Bob Brown, Don Harris, and one of the departing cultists, Patricia Park.

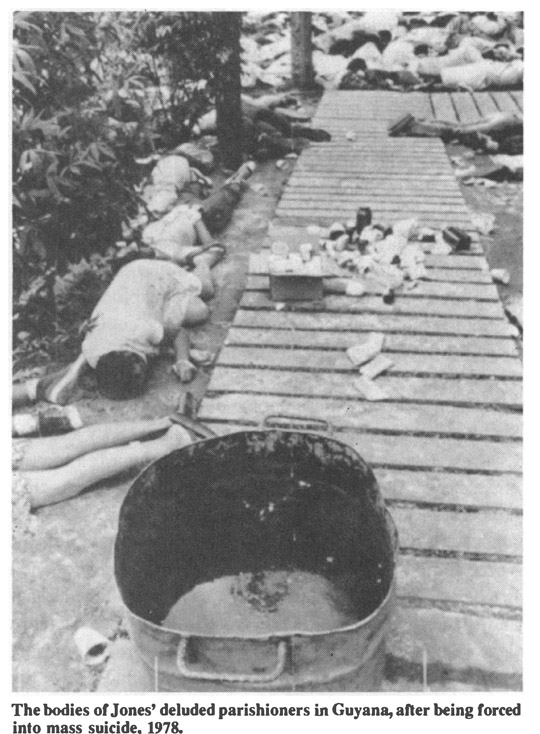

While Ryan and his entourage were being fired upon, Jones was preparing to order his followers to carry out “revolutionary suicide” at the compound. The brainwashed followers, who had rehearsed this scenario dozens of times, were herded into the main pavilion where they received purple Kool-Aid laced with cyanide. Mothers gave cyanide voluntarily to their children. Infants received the substance with a syringe squirting it into their mouths. Next came the older children who received it in paper cups, and finally the adults who accepted the poison as a loudspeaker intoned, “We’re going to meet again in another place!” Those who refused to accept this fate were prodded by heavily armed guards. Within five minutes, most of the 913 victims were dead. Not since the Japanese citizens of Saipan hurled themselves from the rocky cliffs of the island in WWII had the world witnessed anything like this.

Jones, like Adolf Hitler years earlier, killed himself with a bullet to the head. No witnesses survived. Investigators found rows of bodies, most of them lying face down. The U.S. Air Force sent planes to retrieve the remains of the victims while experts in human behavior and sociology grappled with larger issues. “Most members have little or no sense of inner value,” theorized Stefan Pasternack, associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University. “In joining (Jones) they regress and relax their personal judgments to the point that they are supplanted by the group’s often primitive feelings. With a sick leader these primitive feelings are intensified and get worse.”

One person went to trial for complicity in the Jonestown Massacre. Thirty-five-year-old former Quaker Layton, a member of Jones’s death squad, was charged with injuring U.S. diplomat Richard Dwyer and conspiracy to kill Congressman Ryan. The jury in the San Francisco courtroom was unable to agree on a verdict. The courtroom was packed with relatives of the victims when, on Sept. 23, 1981, a mistrial was declared by Judge Robert Peckham.

Jones, Jeremiah, 1913- , Brit. As a youngster, Jeremiah Jones, the son of a London chambermaid, had a violent and unpredictable nature. At only six years old, he was a truant, a delinquent, and a thief. In June 1920, at age seven, he was playing with two younger boys when one refused to give him a toy. He pushed the child into a canal, stoned him, and stepped on his fingers until he drowned. When accused, he testified that the boy had fallen, and the death was ruled accidental.

He soon began to have wild outbursts. When interviewed by child psychiatrist Cyril Burt, Jones admitted to the murder. The other boy agreed, saying that he had remained silent because Jones threatened him. Jones was sent to a series of homes, where his temper remained violent and he developed an intense fear of water. At age nine, he began to show signs of stability. It is unknown what happened to him in his adult life.

Jones, Reginal, d.1982, U.S. A sniper in River Rouge, Mich., killed two people and wounded four on July 18, 1982. The gunman, Reginal Jones, was killed by police when they returned fire. He had begun shooting randomly with a .30-caliber rife from the porch of his second-story apartment. He killed Desiree Burton, a 15-year-old girl, and Mabel Arrington, an elderly woman who was sitting on her porch. Four others, including a River Rouge policeman, were wounded.

Jones, Rex Harvey, prom. 1950s, Brit. Rex Harvey Jones, a miner in the Rhondda Valley of rural Wales, was a man of exemplary character. But after drinking seven pints of beer with his 20-year-old girlfriend, he strangled her. He then called the police and led them to her body. During his trial, the judge told the jury, “You have to steel your hearts against good character and steel your hearts in order to see that justice is done.” Despite this admonishment, the jury made a strong recommendation for mercy. But the judge was adamant, and Jones was hanged.

Jordan, Chester, d.1912, U.S. Chester Jordan and his wife Honora Jordan were actors in Boston in 1908. One day in September, he bought a pair of shears, a hacksaw, and a knife. A few days later, he was seen around town carrying a trunk that was unusually heavy for its size. A hackman reported this to police officers Irving Peabody and Michael Crowley. Two officers went to the Jordan home to investigate. Jordan showed the men the trunk, which held a few light articles of clothing. However, it also emitted a powerful stench, and when asked what was at the bottom, Jordan confessed that it was the torso of his wife. He had struck and pushed her down a flight of stairs. After she died he dissected her, and tried to burn her head and legs. He was arraigned on murder charges on Sept. 3, 1908.

With the help of his brother-in-law, famous stock-market plunger Jesse Livermore, Jordan raised money for his defense. The trial began Apr. 20, 1909, in the Superior Court of Middlesex County in East Cambridge, before Justices William B. Stevens and Charles U. Bell. The prosecution paraded witnesses, including police officers, medical experts, neighbors, a cab driver, and Jordan’s landlady. Particularly gruesome was the exhibition of the late Mrs. Jordan’s skull, tongue, and larynx, all carefully preserved in formaldehyde. The defense countered that Jordan was not mentally fit due to suffering from cerebrospinal syphilis during early manhood. His family agreed, adding their versions of various emotional traumas. The jury was not dissuaded and handed down a Guilty verdict on May 4, 1909.

However, four days later, the jury foreman, Willis A. White, was committed to an insane asylum. The defense appealed the conviction, but the motion was rejected by Justices Stevens and Bell. A further appeal to the Massachusetts Supreme Court was also rejected. On Mar. 12, 1911, with appeal attempts exhausted, Jordan was sentenced to death by execution. The appeal was taken to the U.S. Supreme Court, where it was denied on May 27, 1912. On Sept. 24, 1912, Jordan was electrocuted in Massachusetts.

Jordan, Clayton, 1970- , U.S. On Jan. 9, 1988, Taneka Jones, an 11-year-old girl, was sexually molested and murdered in her home in unincorporated Du Page County, Ill. Her mother found her in a basement storage room the following afternoon. A 10-year-old upstairs neighbor provided testimony which implicated three men: Clayton Jordan, John Kines, and Saul Berry. Jordan was prosecuted in Du Page County Circuit Court before Judge John Bowman.

Jordan had been sentenced earlier to five years on battery charges and was free on bail. He was convicted of the murder and assault of Taneka Jones, and sentenced to serve eighty years for murder, and to serve concurrent terms of thirty years for aggravated criminal sexual assault, five years for intimidation of a witness, and five years for concealment of a homicide. Jordan was ordered to serve out the earlier battery sentence before beginning the murder sentence. Berry received a 70-year sentence and Kines fifty years.

Jordan, Thomas, 1860-1909, U.S. Anton Nolting was a well-educated and popular patrol sergeant when he reported for duty on Jan. 8, 1909, in San Francisco. Shortly after 1 a.m., he heard a shot, and ran to see a soldier with a drawn pistol forcing two other soldiers down the street. When Nolting confronted them, the two hostages were able to flee, leaving the officer to grapple with the assailant. A shot was fired, wounding the officer, and three more were fired, killing him as he lay on the ground. The assailant, Thomas Jordan, was quickly apprehended.

Jordan testified that he was a member of the Coastal Artillery at Fort Baker, but that his mind was a complete blank regarding the shooting of Sergeant Nolting. Hiram Johnson was hired as special prosecutor, and on Mar. 12, 1909, Jordan was found Guilty of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. He died later that year.

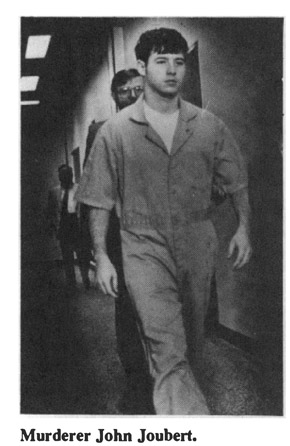

Joubert, John J., 1963- , U.S. A native of Portland, Maine, John J. Joubert joined the Air Force after flunking out of Norwich University in Vermont. Stationed at Offutt Air Force Base near Omaha, Neb., the 21-year-old Joubert was fascinated by detective magazines and their glossy reenactments of sex and violence. In 1983, the fantasy world of Joubert exploded.

Danny Jo Eberle, thirteen, was abducted Sept. 18, 1983, on his way to school. His bound body was found three days later south of Bellevue, Neb. He had been stabbed repeatedly. Three months later, on Dec. 5, the brutalized body of Christopher Walden, twelve, was found north-west of Papillion, Neb. The autopsy reported that Joubert had first tried to strangle the boy and then stabbed him five times. While there was no evidence of sexual assault, both boys were forced to strip down to their underwear before being killed. On Jan. 11, 1984, Joubert was arrested for the murders of Eberle and Walden.

During his trial, psychiatric evidence showed that Joubert had been fantasizing about bizarre acts with women and young boys since he was six years old. Police found twenty-four detective magazines in his room, and Joubert admitted to having sexual fantasies about the captives depicted in them. On July 3, 1984, Joubert confessed to the murders of Danny Jo Eberle and Christopher Walden.

Three months later, a three-judge panel sentenced him to death. The parents of both victims had implored the court to give Joubert the death sentence, while Beverly A. Joubert had asked that her son be spared so that he might help other prisoners. John J. Joubert awaits execution at the Nebraska State Penitentiary in Lincoln.

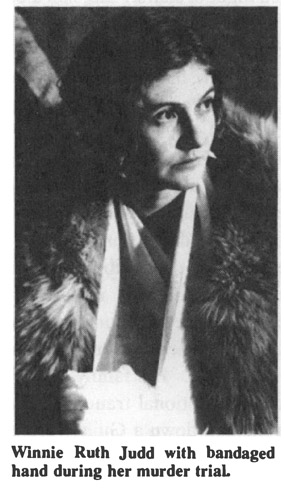

Judd, Winnie Ruth (Winnie Ruth McKinnell), 1906-, U.S. Born and raised in a well-to-do Illinois family, Winnie Ruth Judd moved to California to study nursing and there met and married an elderly, wealthy physician, Dr. William J. Judd. She contracted tuberculosis and was sent to the desert community of Phoenix where it was hoped the dry air would cure her condition. In 1931, Judd moved in with two of her best friends, Agnes Ann LeRoi, thirty, and Helwig Samuelson, twenty-three. The three women shared a trim bungalow and all went well for some months. But then Judd, according to later statements, began to harbor deep resentment toward LeRoi and Samuelson who, she claimed, were stealing her male friends.

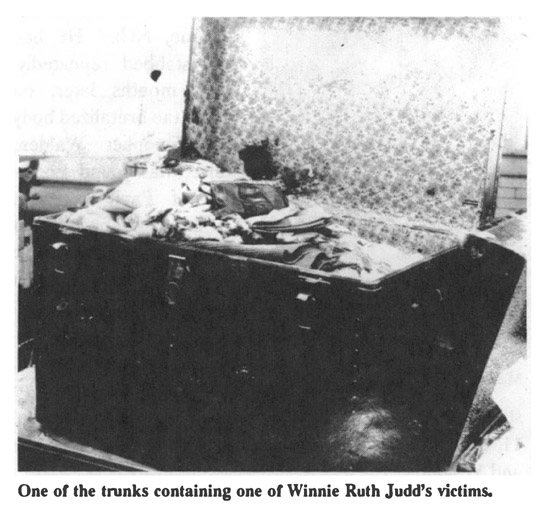

Judd was then twenty-five, had a curvaceous figure, copper hair, and large blue eyes. She confronted her two friends on the night of Oct. 16, 1931, and asked them why they were interfering with her love life. Both women laughed at her, she later claimed. With that, Judd pulled a small revolver and shot both women dead. She crammed their bodies into a trunk and booked a reservation on the Golden State Limited, intending to return to California. For some strange reason, she intended to take the bodies of her friends with her. A train porter arrived at the bungalow and told Judd that the trunk was too heavy to be shipped as personal luggage. Winnie told him that it contained important medical books belonging to her husband. The porter suggested that she rearrange the books into two trunks, and she agreed. She had the porter take the large trunk to an apartment she had rented and there she removed Samuelson’s body, and sawed it into pieces so that it would fit into a smaller trunk and a suitcase. She then shipped these three pieces of baggage to Los Angeles and climbed aboard the Golden State Limited.

Once she arrived in Los Angeles, Judd took a taxi to the University of Southern California, going to the political science building to see her 26-year-old brother, Burton J. McKinnell. When he arrived, Winnie implored McKinnell to accompany her to Union Station to retrieve her trunks. “You must help me get them right away!” she told him. “We must take them to the beach and throw them into the ocean!” She was frantic and her hand was bandaged. (Judd had fired a bullet into her own hand at the time of the LeRoi and Samuelson killings so that she could later claim she had been shot by LeRoi and had killed the two women in self-defense.) McKinnell, so as not to agitate his sister further, agreed to help her. They went to Union Station and, at the baggage counter, claimed the two trunks and large suitcase. Baggage clerk Andrew Anderson, however, suspected that Judd and her brother, who had no idea that his sister was a murderer, were meat smugglers. Hunters had recently shot deer illegally in Arizona and had been secretly shipping venison to Los Angeles in trunks.

One of the trunks smelled like a dead animal, Anderson believed, and the other trunk was seeping a dark, gluey substance. He told Judd and her brother that he had to inspect the baggage she was claiming before he could turn it over to her. Judd quickly answered that only her husband had the keys to the baggage and she would have to get them first. She turned on her heel and walked quickly away, her puzzled brother following. Anderson trailed the pair to the parking lot and there spotted the couple getting into a car. He wrote down the license plate and then called the police. Two detectives arrived at the station and broke open one of the trunks. They stepped back in shock. Some spectators standing nearby became ill at the sight of Samuelson’s dismembered corpse. A woman fainted.

Police traced the license number Anderson had written down to McKinnell, who was then meeting with Dr. Judd. He told detectives that his sister had told him as they drove away from Union Station that there were “two bodies in those trunks and the less you know about it, the better off you are.” She had borrowed a few dollars from him and then gotten out of his car at Sixth and Broadway in downtown Los Angeles, disappearing into a crowd. A police dragnet for Winnie Ruth Judd ensued but she was nowhere to be found. Judd was, at the time, hiding in an unused building on the grounds of the La Vina Sanitarium in Altadena where she had once been a tuberculosis patient. She remained in the empty building for three days, sneaking into the sanitarium’s kitchen at night to steal food. Meanwhile, her hand, which bore a gunshot wound, became infected. After three days, Judd picked up a newspaper and read an ad which her husband had placed, in which he begged her to surrender herself.

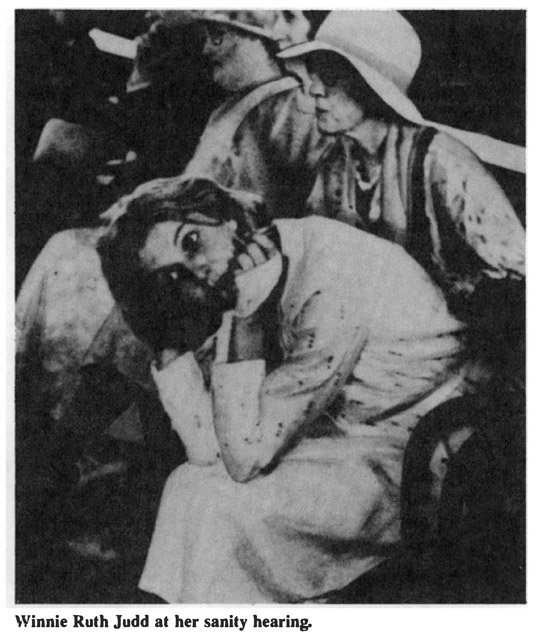

Winnie contacted her husband, who took her to a clinic where her hand was treated. Police then arrived to arrest her. She was extradited by the state of Arizona and tried for the murders of LeRoi and Samuelson. Winnie at first claimed that she had killed her two friends in self-defense. She held up her hand and said that Samuelson had shot her in the hand and that she had struggled with her, grabbing the gun and shooting first Samuelson, then LeRoi when the other woman also attacked her. The jury, believing that Judd had shot herself in the hand to support her claim of self-defense, convicted her and sentenced her to death. While awaiting execution, prison doctors became convinced that Judd was insane and a mental hearing was held. Winnie’s mother and other relatives stepped forward to state that the McKinnell family had, for generations, been afflicted by insanity.

Winnie made a great show of being deranged. She pulled at her hair, constantly ripped away at her clothes, mumbled to herself and, at one point, leaped up and pointed to the jury and shouted: “They’re all gangsters!” She later called her husband to her side and said, loud enough for the courtroom to hear: “Let me throw myself out that window!” Guards finally had to be called in to remove Winnie, who had become hysterical. It was agreed that she was hopelessly insane. Her death sentence was commuted to a life sentence in the Arizona State Mental Asylum. She escaped many times. Once she made a “sleeping dummy” of herself and fled into the wilderness, walking many miles before she was picked up by a motorist who returned her to the institution. “When she looked at you with those great big eyes brimming with tears you would believe anything she told you,” stated a nurse.

In 1952, Judd escaped again but was recaptured. She was brought before a committee looking into conditions in mental hospitals. Before she could testify, guards found a passkey hidden in her hair and a razor secreted under her tongue. She escaped again in 1962 and managed to reach Concord, Calif. There she became a live-in housekeeper for John and Ethel Blemer, earning additional money as a baby sitter for neighbors. She was recognized on a street in 1969 and arrested. She managed to fight extradition back to Arizona for some time, defended by Melvin Belli, but the governor of California, Ronald Reagan, returned Judd to Arizona.

On Dec. 22, 1971, the Arizona Parole Board commuted Judd’s life sentence to time served and she was released on the provision that she live out her life in California. She returned to the Blemer home to resume housekeeping duties. Ethel Blemer died in 1983 and Winnie sued for a goodly portion of the Blemer estate, claiming that the Blemers, since her 1971 parole, had kept her a virtual “indentured servant,” and that she had been “thrown out” of the Blemer home after Ethel’s death by other Blemer relatives. She was eventually awarded a $225,000 settlement, plus $1,250 a month for life.

Juenemann, Charlotte, 1911-35, Ger. Charlotte Juenemann kept her three children locked in a basement room until they died in 1935. The woman, whose husband was in an insane asylum, had been given welfare money but refused to apply it to the children. Instead, she became enamored with a musician and spent the money on nightlife. At the time of her arrest, she was pregnant.

On Mar. 30, 1935, Juenemann was sentenced to death by beheading. Nazi Germany’s new justice also determined that her unborn baby would be a debit to the race. The sentence was carried out on Aug. 27, 1935, at Plotzenee Prison.