Kaber, Eva Catherine, d.1931, and Calla, Salvatore, and Piselli, Vittorio, and Colavito, Erminia (AKA: Big Emma), prom. 1919, U.S. Publisher Daniel D. Kaber of Cleveland, Ohio, thought someone, his wife perhaps, was trying to kill him. For months he lay motionless in his bed at the family home in plush Lakewood after suffering a stroke. Paralysis set in, despite the constant attention of physicians, who were convinced that he had a rare stomach disorder.

On July 18, 1919, a hideously penetrating scream was heard from Kaber’s room. F.W. Utterbach, a male nurse on duty in the house, rushed into the room to find Kaber lying in a pool of blood on the floor, slashed repeatedly by a knife-wielding assailant. An ambulance carried him to the Lakewood Hospital where he died a few hours later, his last words fueling speculation that the murderer had been hired by a family member. “The man in the cap did it,” he gasped. “That woman had me killed.” Moses Kaber, the dead man’s 75-year-old father, was convinced that his daughter-in-law Eva was responsible because during her husband’s illness she had shown little concern, and on the night of the murder was vacationing at a popular lake front resort, leaving her flapper-daughter Marian McArdle and Mary Brickel, Kaber’s mother-in-law, to attend to Daniel.

Eva’s first two marriages had ended in divorce. She had lived an impoverished life. When she married Kaber in 1911 her driving ambition was to attain a degree of wealth for herself and Marian. At the coroner’s inquest, Eva Kaber denied the charges brought against her by her father-in-law and Prosecutor Samuel Doerfler. Since her alibi was unshakable the case was dismissed. Eva collected the insurance money due her, sold the house, and moved to New York to open a millinery shop. Daughter Marian followed her east and became a chorus girl in Pretty Baby. Back in Ohio, Moses Kaber continued the investigation. He hired Pinkerton agents to follow Eva Kaber and also posted a $2,000 reward. Two women came forward, Mrs. Ethel Berman, a former acquaintance of Eva, and Mrs. M.A. Deering. In New York, Berman had renewed her friendship with Eva and went to work in the millinery shop as a secretary. Meanwhile, Deering got to know Mrs. Brickel who freely admitted that her daughter “did it for the money.”

Nearly two years passed before the Cuyahoga County district attorney wired New York police to arrest the widow Kaber and her daughter on suspicion of murder. They were brought in for questioning on June 2, 1921, after Mrs. Berman had pieced together an incredible story. She had found out that Eva had consulted with a number of psychics to determine the time when her invalid husband would die. Dissatisfied with what they told her, she resorted to more direct methods. A $5,000 “bounty’’ was placed on her husband’s head, but her chauffeur, Frank DiCarpo, was not interested in collecting. Next, she went to a pair of mediums who refused to conjure up “evil spirits” to carry out a murder.

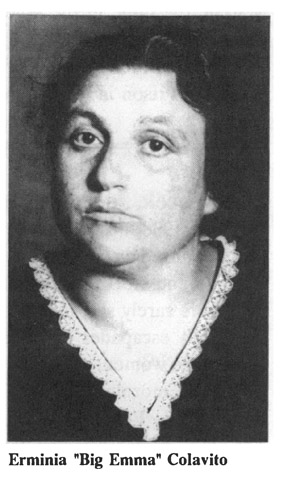

Finally, Eva found a soul mate in Mrs. Ermina “Big Emma” Colavito of Sandusky, who promised to deliver a special medicine to hasten Kaber’s demise. What she had in mind were two hired thugs whose names were Vittorio Pisselli and Salvatore Calla. The murder-for-hire scheme was given its final blessing by Mrs. Brickel, who had given the conspirators the “all-clear” signal. Calla was arrested in Buffalo. Pisselli had fled to Italy after the murder, but was picked up there and jailed. Eva confessed to her role in the plot but refused to implicate her daughter Marian.

The charges against Mrs. Brickel were dismissed, and Marian, the dupe in the scheme, was acquitted. But the other defendants received life sentences. Eva Kaber, often described as the “meanest prisoner in Ohio,” died in the Women’s Prison in Marysville in 1931.

Kadlecek, Joseph (AKA: Joe Cadillac), prom. 1938, U.S. In 1938, Joseph Kadlecek, known to many as Joe Cadillac, lived in a rooming house on the West Side of Chicago and worked in a Fulton Street box factory. His neighbors rarely saw him, but they were familiar with his late night escapades which always involved alcohol and sometimes women.

On the morning of Nov. 17, a maid found the naked body of Ella Pehrson, twenty-eight, in Kadlecek’s closet. The smell of death mixed with the overpowering scent of perfume in the tiny room. Pehrson, who sold beauty supplies, had been stabbed repeatedly and sexually assaulted after her death. Chris Stavard, the landlord of the rooming house on Warren Avenue, told police that Cadillac kept to himself, paid his rent on time, and was missing a finger on his right hand from a recent industrial accident. The victim had lived just blocks away at the West Manor Hotel on South Ashland Avenue.

Kadlecek was arrested outside the Lawndale National Bank on 26th Street when he tried to withdraw money from a bank account he shared with his brother. He admitted he was a regular business customer of the murder victim, but said he didn’t kill her. Hours later, Kadlecek claimed he found Pehrson’s body in his room and stuffed her in the closet in panic. Still later, he admitted that he murdered her and assaulted her after she resisted his sexual advances. He said he soaked the room in perfume to cover up the stench of the bloody corpse. On Jan. 9, 1939, Judge Walter Stanton sentenced Kadlecek to sixty years in prison. “I had it coming—and more,” Joe Cadillac said. “I couldn’t have beefed if the judge had given me the hot seat.”

Kagebien, Joey Newton, 1956- , U.S. When Joey Kagebien of De Witt, Ark., was sentenced to die in the electric chair for the 1971 murder of 27-year-old Jimmy Wayne Wampler, he became the youngest person to sit on Death Row.

Wampler, a prosperous rice farmer from Wynne, Ark., had purchased three six-packs of beer at a small general store in Gillet for his 15-year-old friend Kagebien, who was going on a hunting trip with three friends: Teddy Kittler, sixteen, Larry Mannis, seventeen, and Benny West, sixteen. According to Kagebien, Wampler approached them for sex, and when his request was denied Wampler became abusive. Kittler shot Wampler after Kagebien struck him over the head with a rifle butt. His naked body was found late that night after the boys reported the crime to De Witt police chief, James Mason.

The youths claimed it was an act of self defense. But the jury in the first of two sensational murder trials disagreed. Kagebien was found Guilty and sentenced to die in the electric chair. Because of Kagebian’s youth, Governor Dale Bumpers was flooded with petitions to commute the sentence. Responding to public pressure, the governor stayed Kagebien’s execution in September 1971, a month before he was scheduled to die.

In January 1974, the Arkansas youth was granted a second trial by the state supreme court. It was held before Judge Andrew Ponder, who found the defendant Guilty of second-degree murder. Under Arkansas law, anyone who aids and abets a murderer is as guilty as the person who actually committed the crime. Joey Kagebien was sentenced to twenty-one years in prison, with twelve years suspended. Teddy Kittler, who pulled the trigger, received a life term. The two accomplices, Benny West and Larry Mannis, were given sentences of twenty-one years and twenty years, respectively.

Kantarian, Nancy Lee, 1954- , U.S. In a moment of unexplained frenzy, the 30-year-old daughter of media tycoon John Heselden, deputy chairman of Gannett Corp., publishers of the USA Today newspaper, murdered her two young children and set fire to her spacious home in the Great Falls section of Fairfax County, outside Washington, D.C. The tragedy occurred the night of May 23, 1984. Nancy Lee Kantarian was alone in the house with her children, preparing them for bed. Her husband Harry, a Washington-based attorney, was in Denver on business.

Police and fire officials puzzled over just what transpired inside the $400,000 suburban house before they arrived. When they appeared the residence was ablaze and Kantarian was at her neighbor’s home sobbing incoherently. Inside the burning house they found 5-year-old Jamie Lee Kantarian and her 6-year-old sister, Talia, lying unconscious. The younger girl was pronounced dead at the scene, killed by the fire. Talia Kantarian died as a result of thirty-two stab wounds inflicted by her mother. At first Mrs. Kantarian told police the children were responsible for the fire, but later amended this story. “Jamie was angry…She built …she wouldn’t sleep… she piled blankets to make a house when she should have been sleeping,” Kantarian sobbed. “I got mad… Harry was gone…I get so frightened.”

Nancy Kantarian pleaded guilty to murdering her two children in an emotionally charged hearing before Judge Bernard Jennings in the Fairfax County Circuit Court on Oct. 2, 1984. “There is no question that the killings are the result of some form of mental or emotional sickness,” said Prosecutor Robert Horan, who supported a recommendation to hospitalize the woman rather than send her to jail. Judge Jennings agreed. On Oct. 6, he sentenced Kantarian to the maximum of ten years in prison on two counts of manslaughter, but suspended it on the condition that she enter a private facility to be paid for at the family’s expense. “There is no need to incarcerate you as a deterrent to others,” Jennings stated. “And I don’t think we really need to protect society from you.”

Kaplan, Joel David, 1927- , U.S. Thirty-four-year-old Joel David Kaplan entered Mexico in 1961 as president of the American Sucrose Company, a U.S. firm owned by Kaplan’s uncle, J.M. Kaplan. In November of that year, the treasurer of American Sucrose, Luis Melchior Vidal, was reportedly shot to death and a body initially thought to be his was found on the road to Cuernavaca. Kaplan and two other men, Harry Kopelsohn and Evsle S. Petrushansky were arrested and charged in the murder. Kaplan fled Mexico but was arrested in Spain by Interpol and returned to Mexico City. He was convicted of Vidal’s murder in late 1962 and sentenced to serve twenty-eight years in prison.

Kaplan’s uncle was also the founder of the Kaplan Foundation in New York, which has been identified in Congressional testimony as one of the otherwise philanthropic agencies used for channeling CIA funds to labor and student organizations. Joel Kaplan had a long-standing interest in the politics of Third World countries and was rumored to have acted as a mercenary in various Caribbean and Central American locations. Kaplan, once in prison in Mexico City, hinted broadly at having served in the CIA. Furthermore, it was rumored that Vidal had been a supplier of arms to Third World countries. Additionally, Kaplan’s attorney claimed that the body purported to be that of Vidal was actually that of a man twice Vidal’s age, bearing little or no physical resemblance to Vidal.

On Aug. 18, 1971, Joel Kaplan, who had already made several attempts to escape from prison, finally succeeded. While the guards at Santa Maria Acatitla prison watched a movie, Kaplan and another inmate, Carlos Antonio Contreras Castro, dashed across a courtyard to a waiting helicopter and flew away. The escape was reportedly arranged and paid for by Kaplan’s relatives.

The helicopter flew to Actopan, Mex., where a small plane piloted by Victor E. Stadter waited to take them to La Pesca, Mex. There, Castro, a pilot who was serving a prison sentence for swindling, left for a destination in Mexico while Kaplan and his pilot headed for the U.S. When the plane reached the border at Brownsville, Texas, shortly before midnight, Stadter notified U.S. Customs of their approach, giving his own name and Kaplan’s as the plane’s passengers. It was later surmised that this identification was necessary because Kaplan had to be in the U.S. legally in order to claim an inheritance that awaited him. Stadter flew Kaplan, who was reported to be ill, to an unknown destination where he went into hiding. Neither the U.S. nor the Mexican governments appeared very interested in tracking Kaplan down. Due to a loophole in Mexican law which makes prison escape illegal only if violence is used, Kaplan had committed no further crime.

Kashney, Roland, 1937- , U.S. The 1970 armed robbery and slaying of 65-year-old Margaret Riggins and the 1974 armed robbery and slaying of 55-year-old Benjamin Peck in Chicago, Ill., remained unsolved until a former girlfriend of Roland Kashney informed police that he had committed the crimes. In 1974 when police arrested Kashney, a self-proclaimed evangelist, he confessed to both murders and armed robberies, but claimed that he had been forced by the devil to do it. Kashney was found unfit to stand trial and was committed to a state mental hospital.

Kashney spent five years in the hospital before he was found sane in October 1979 and ordered to stand trial. During the May 1981 trial, 43-year-old Kashney denied committing the crimes, claiming that he had confessed to them earlier only because the police officers questioning him were possessed by the devil. Kashney claimed that he could see the devil squeezing the heads of the officers and confessed because he was afraid of the demons. In spite of testimony from two “demonologists,” the jury found Kashney Guilty of Peck’s murder but Innocent of both armed robberies and the Riggins murder. He was sentenced to thirty to sixty years in prison.

Kasper, Karl, 1933- , Ger. Karl Kasper of Rotzel, Ger., summoned the local physician to come at once to his home on Nov. 5, 1972. The 39-year-old farmer had come home from the fields and found his wife dead in her bedroom.

Dr. Harald Nussbaum concluded that Ingrid Kasper’s death was neither accidental or natural. A coroner from Waldshut concluded she had been electrocuted while in a state of extreme sexual agitation. The Kaspers had been married for fourteen years, and had three children. At first it seemed unlikely that Kasper would kill his wife.

But the facade of marital bliss was soon ripped away by investigators. Kasper was heavily in debt, partly because of the money he had borrowed to purchase the farm. He had a mistress, Erika Jung, whom he met through an ad in a local newspaper, and was fond of aberrant sexual activities. Mrs. Kasper died from a massive electrical shock from a pair of medical tongs intended to provide sexual stimulation.

Kasper claimed the murderer was Luigi Antoninni, an Italian who allegedly had intercourse with Ingrid. The Italian had left the country, and it was unlikely that he was involved. The electrical cords used to kill Ingrid were later found in her husband’s car. Confronted by this evidence, he made his confession. It was an accident during sex, he explained. But he also had taken out a life insurance policy on his wife six months before her death. On Oct. 5. 1973, Kasper was found Guilty of murder and sentenced to twelve years in prison.

Katz, Arthur, 1934-87, U.S. The stock market crash of October 1987 exacted a heavy toll, not only financial, but in human lives as well. Across the nation there were reports of distraught financial speculators committing acts of violence. Arthur Katz of Miami walked into a Merrill Lynch brokerage office on Oct. 26, 1987, and asked to speak with the manager. Katz was well known to the office workers as major investor who apparently did not understand the dangers of buying stocks on margin. Katz casually opened a briefcase and pulled out a gun, which he turned on himself after killing Jose Argilagos, fifty-one, and his broker Lloyd Kolokoff, thirty-eight, both Merrill Lynch vice presidents.

Katz had suffered serious financial reversals since moving to Florida in the 1970s under the witness protection program. He had been involved in a stock manipulation scheme and had started over in Miami as a Social Security claims examiner. His passion, however, was the world of high finance. When his creditors called in his accounts after the crash, Katz became desperate. He vented his anger against the system with a gun.

Kauffman, Paul, prom. 1930, U.S. The newspaper want ad asked for a girl to care for a small child for $10 a week. To Avis Wooley, a 17-year-old girl from Webb City, Mo., it seemed like the ideal job. She agreed to meet the man who identified himself as Paul Kauffman, a young widower with one child.

She left home on Aug. 17, 1930, and was never seen again. The only indication that her mother received that her daughter was still alive was a telegram, dated Aug. 17, which read: “Like job very much. Will write later. Love Avis.”

On Oct. 12, Alfred Erickson was walking through Swope Park in Kansas City when he stumbled over a skull which forensic experts identified as that of a young woman. The remains were Avis Wooley’s. When the police investigated the ad placement in the Kansas City newspapers, they learned that Paul Kauffman was a fictitious name. The man who used this alias had been arrested before for imprisoning a teen-age girl in his room.

When Kauffman was arrested and taken into custody he told the Kansas City police chief that after picking up Avis at the train station, they had walked through Swope Park. When he offered her a drink, she refused. A quarrel ensued when the girl insisted on going home. It was then that Kauffman strangled Avis with her nylon stockings. He then robbed her of seventy cents. For killing Avis, Kauffman was found Guilty of murder in the first degree and was executed at the gallows.

Kawananakoa, David Kalakaua (AKA: Prince Koke), 1904- , U.S. David Kawananakoa was the last surviving male member of the Hawaiian Royal family. His grand-uncle, David Kalakaua, earned a reputation as a lustful, fun-loving playboy known to play poker for hours on end.

Like his uncle, Kawananakoa had a yen for the fast life, and could frequently be found cavorting with the island girls on the Flapper’s Fast Acre, Honolulu’s night club district and sin-strip. Prince Koke got into trouble for the first time in 1932 when Felicity Connors of California was killed in an automobile crash. He was given a five-year probation, but violated the terms of the sentence when he openly lived with Arvilla Kinslea, a 22-year-old Hawaiian-American.

In October 1937, Kawananakoa was arrested a second time when he assaulted his live-in lover with a crockery shard during a beach party held in his cottage, adjacent to the “strip.” When the police arrived they found Kinslea’s body wrapped in a sheet and bleeding from the neck. The prince, Major Bernard Tooher of the U.S. Army, and two other guests stood by as police surveyed the ransacked cottage.

Prince Koke pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to ten years in the Oahu Penitentiary by Judge H.E. Stafford.

Kearney, Frank, d.1925, U.S. When a thief tried to rob tailor Harry Hamburg, the tailor testified against the man, who, convicted and sentenced to a jail term, swore he would get revenge. Months later Hamburg was shot and killed on New Year’s Eve.

A phone call on Dec. 31, 1924, brought police to Hamburg’s shop in Boston’s South End. A hard-working, courageous man, Hamburg had battled it out with thieves before. This time he lost his life. Owners of the fruit store next to Hamburg’s shop had called in when they heard sounds of a struggle and then a gunshot, and saw two men in overcoats running away.

Police investigators Louis DiSessa, Captain Driscoll, and Sergeant Gale discovered that Joe Colanso, convicted for attempting to rob the tailor months earlier, was serving a prison term at the Reformatory in Concord, Mass. Though Colanso had sworn revenge, he could not be connected to Hamburg’s murder. Soon after questioning him, a police officer discovered an overcoat in an alley and a 32-caliber pistol in a garbage can, both near the scene of the killing. The slugs matched those found in Hamburg’s skull, and the coat was identified by the fruit sellers as one worn by one of the fleeing men. The pistol, tracked to sailor John Moran, had been lent by him to a woman he had picked up at a Fraternity Hall dance. She wanted to borrow it for her husband who, she explained, needed to kill a rat. Through the manager of the dance hall police eventually learned the husband’s name was Frank Kearney, and picked up his accomplice, young Harry Alexander. Alexander insisted that Kearney had committed the crime. When Kearney’s wife was brought in, she said her husband had disappeared after talking about traveling around the world as a sailor. Alexander was tried and given a thirty-year jail term on charges that included armed robbery. False leads on Kearney’s whereabouts went on for years, and his wife eventually divorced him in absentia.

In July 1941 the FBI in Washington wired the Boston police that a man answering Kearney’s description had been picked up at the Arizona-Mexico border. A virtual derelict, Kearney had spent seventeen and a half years fruitlessly trying to escape the haunting images of his past and of the murder as he traveled the world as a sailor. He kept his identity a secret for some time by using the passport of a Spaniard who died of natural causes and he later fought for the Loyalist army in Spain. Kearney also worked in France and Mexico, and finally was picked up by a border patrol.

Tried on Nov. 17, 1941, Kearney pleaded guilty to reduced charges of manslaughter and was sentenced to nineteen years in prison. In 1945, sick and listless, he was transferred to the penal colony in Norfolk where he became violently ill and died a few days later, the cause of his death a mystery. One theory said he had died from a tropical disease picked up during his travels and another claimed that he had taken poison.

Kearney, Patrick Wayne, 1940- , U.S. On July 13, 1977, an electronics engineer for the Los Angeles Hughes Aircraft Co. was indicted on three counts of murder by a Riverside, Calif., grand jury. Charges against his roommate and best friend, David D. Hill, thirty-four, were dropped because of lack of evidence. Patrick Kearney was being investigated in connection with at least twenty-eight murders of homosexual men.

Hill and Kearney, roommates for fifteen years, turned themselves in to authorities on July 1, pointing to a wanted poster with their pictures and announcing: “We’re them.” Most of the information about the killings came from Kearney’s statements to police. Bodies of many of the victims were found in plastic garbage bags along highways from south Los Angeles to the border of Mexico and several of the corpses had been dismembered after being shot. Kearney was indicted for the slayings of Albert Rivera, twenty-one, Arturo Marquez, twenty-four, and John Le May, seventeen. The first victim, Rivera, was found in April 1975, with five more bodies turning up by the end of 1976. All the victims were nude, shot in the head with a small-caliber gun, and dumped alongside the highway. Almost all were transient young men who frequented the homosexual cruising areas and hangouts in and around Los Angeles and Hollywood.

At Hill and Kearney’s Redondo Beach home investigators found a hacksaw which proved to be stained with Le May’s blood, as well as hair and carpet samples which matched those on tape found on the victims’ bodies. Kearney and Hill had fled to Mexico, but surrendered when persuaded by relatives to turn themselves in.

On Dec. 21, 1977, Kearney pleaded guilty to three murders and was sentenced to life imprisonment by Superior Court Judge John Hews. On Feb. 21, 1978, Kearney pleaded guilty before Judge Dickran Tevrizzian, Jr., to eighteen slayings of young men and boys in exchange for a promise from the prosecution that he would not be given the death penalty. Kearney also provided details of the related killings of another eleven homosexual men, bringing the probable total to thirty-two victims.

Keeling, Frederick, 1868-1922, Brit. Frederick Keeling returned to his career as a plasterer following his time in the army, and became landlord of a boarding house in St. George’s Road, Tottenham. The muscular 53-year-old was a blunt and aggressive man who did not drink but had a penchant for romance. For years, one of his boarders, Emily Dewberry, stayed in his room so often that she came to be known locally as “Mrs. Keeling.”

At the end of 1921, Dewberry and Keeling broke up. Keeling soon became involved with Mrs. Haynes, a melancholy alcoholic, a relationship that galled Dewberry and influenced Keeling to drink as heavily as Haynes, whom he often beat up, as he had Dewberry and others.

When an inspector from the Ministry of Pensions came for a routine inquiry about Keeling’s “wife,” a deceit the landlord had practiced for years to increase his pension, the angry Dewberry overheard their talk from another room in the house. She called out to the inspector as he was leaving and told him all about Keeling’s domestic status. Arrested a few days later, Keeling was brought before a magistrate, charged with fraud, and informed that he would be tried with Dewberry as a witness against him. Released on bail, Keeling drank excessively, beat up Haynes, leaving her unconscious, and disappeared. When the case came up the following day, Keeling had vanished and Dewberry was found murdered in her room, brutally beaten with a plasterer’s hammer. Police searched for ten days, capturing Keeling when a charwoman, aware of the reward, followed him and had him arrested.

Tried in front of Mr. Justice Darling on Mar. 6, 1922, Keeling was found Guilty and sentenced to death. Haynes, called as a witness for the prosecution, was morose at the trial and, when the judge made a facetious remark, cried out bitterly, “Laughter in court. I suppose they’ll put that in the paper.” Keeling was hanged on Apr. 11, 1922.

Keeton, Ouida, prom. 1935, U.S. In January 1935, in Laurel, Miss., a hunting dog led its master to two mysterious-looking parcels. The parcels contained parts of a human body. The police found evidence of a car having been stuck in the soft ground near where the packages were found. Local garage employees said that a popular young local woman, Ouida Keeton, had gotten her car stuck in this spot recently and had been towed out by garage employees.

When she gave police an obviously fabricated and easily disproved story about her mother being away on a visit to New Orleans, the police pressed her for more information. Then Keeton said that her mother and she had been kidnapped and the mother held for ransom. The police did not believe this story, and Keeton concocted yet another in which she had been seduced by a former employer, an older man, who had murdered her mother to give them greater freedom. The man had assigned her the task of disposing of the body parts which she had attempted to do. Parts of the mother’s body were never recovered but evidence in the home indicated that the murder had most likely taken place there, and the murderer had burned a portion of the remains in the fireplace. On Mar. 13, 1935, a jury found Ouida Keeton Guilty of murder and sentenced her to life in prison. Despite Keeton’s conviction, police expected to bring murder charges against her former employer, 67-year-old W.M. Carter. Keeton had accurately predicted Carter’s alibi, causing police to suspect his collusion in the crime.

Kehoe, Andrew, 1882-1927, U.S. Andrew Kehoe was a fastidious farmer, an electrician, and the treasurer of the Bath, Mich., school board. The 45-year-old’s tubercular wife had been in and out of hospitals for the past year and the medical bills were mounting. He was on the verge of losing the farm he had tended so meticulously for the past eight years. Kehoe was also stealing money from the school treasury to make ends meet.

Two years earlier, the childless Kehoe had vehemently opposed a tax increase to build a new school in Bath, a farming town twelve miles northeast of Lansing. He said it would bankrupt local taxpayers. But Kehoe was alone in his opposition, and the new Bath Community Consolidated School was built. The three-story brick structure housed nearly 300 students and teachers from across the county while Bath itself had only 250 residents.

Kehoe, a depressed and bitter man, did not plant a spring crop in 1927. When Sheriff Fox served him with the foreclosure notice, Kehoe reportedly told him: “If it hadn’t been for that $30 school tax, I might have paid off this mortgage.”

Early on the morning of May 18, Kehoe set in motion a plan he had been working on for months. First, he killed all the fruit trees on his farm. Then he crushed his wife’s skull and tied her to a cart. He then set off the dynamite charges that he had placed near his farm buildings. Next, he drove to town and cut the wires to the central telephone office. Kehoe’s last stop was the school.

Andrew Kehoe was sitting in his car shortly before 10 a.m. when he triggered the dynamite blast that buckled the floors, blew out the walls, and lifted the roof off the north wing of the school building. The force of the explosion sent bodies flying into the schoolyard. A second, more powerful explosion collapsed the building inwards, burying many fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-graders, and their teachers. When Superintendent Emery E. Huyck sprinted toward the car, Kehoe fired a shot into the back seat, which was loaded with explosives. Huyck and Kehoe were killed instantly, their bodies thrown thirty feet in the air.

Authorities removed three bushels of dynamite that Kehoe had rigged to destroy the rest of the school. If a janitor had not shut off a light switch to make some repairs, the entire school would have been leveled. Thirty-seven children and seven adults died in the explosions and more than fifty others were injured.

Wired to the fence in front of Andrew Kehoe’s charred farmhouse was a crude sign that read: “Criminals are made, not born.”

Kelbach, Walter, 1938- , and Lance, Myron, 1941- , U.S. Eight days before Christmas 196, Walter Kelbach, twenty-eight, and his friend Myron Lance, twenty-five, went on a killing spree that left six people dead. A 1972 television NBC documentary titled “Thou Shalt Not Kill” profiled these two killers from Salt Lake City, Utah. The two ex-convicts were also lovers and had consumed large amounts of drugs the night of Dec. 17, 1966. Kelbach drove to a Salt Lake City gas station where the two robbed an attendant of $147 and forced him into the back seat of their station wagon. They drove into the desert where, after forcing their victim to engage in sex, Kelbach stabbed him repeatedly and threw the body into a roadside ditch. Victim number two was Michael Holtz, who also worked in a filling station. He was abducted and murdered in the same fashion, this time by both Kelbach and Lance. Police issued a citywide order that all gas stations be closed at nightfall.

Four days before Christmas, Kelbach and Lance got into the back seat of a taxi belonging to Grant Creed Strong. Suspicious about the two grinning men who wanted to go to the airport, Strong radioed the dispatcher. He said that if he encountered problems, he would click his microphone twice. As the taxi pulled over to the curb, Lance thrust a gun at Strong’s head and demanded all his money. Strong handed over $9, which angered Lance, and he shot Strong through the head.

The two men proceeded to Lolly’s Tavern, near the airport. Announcing to the stunned patrons that this was a stickup, Lance casually shot 47-year-old James Sizemore through the head. The killers took $300 from the till and sprayed the bar with gunfire, killing Beverly Mace, thirty-four, and Fred William Lillie, twenty. Kelbach and Lance fled, but were soon captured at a police roadblock. They were charged with first-degree murder, convicted, and quickly sentenced to death. But when the Supreme Court outlawed capital punishment, the pair were spared. Neither killer ever expressed remorse. “I haven’t any feelings towards the victims,” Lance said. “I don’t mind people getting hurt because I just like to watch it,” Kelbach added. Both men are being held at the Utah State Penitentiary.

Keller, Eva, prom. 1947-50, U.S. On Jan. 25, 1947, Max Keller’s neighbors forced open a kitchen window of his suburban Los Angeles home when they had not seen him for several days. They found his body in the den. Police investigators Edgar Kortan and Newt La Fever discovered that Keller had been shot and killed with two 38-caliber bullets. There was no sign of a struggle, indicating that he knew his assailant. Though he still wore an expensive gold watch, his wallet was missing. Neighbors and relatives recalled that he had recently changed the locks of his home because small valuables were disappearing. Also, a suspicious gas explosion occurred at his home on New Year’s Eve, not long after he and his wife of twenty-two years, Eva Keller, had separated. Keller had recently changed his insurance policy, naming his stepdaughter, Elsie Keller Petrichella, beneficiary instead of his estranged wife. Hearing of her husband’s death, Eva Keller burst into tears, saying he must have been slain by “a jealous husband or a boyfriend of one of those women,” referring to girlfriends she insisted he had been seeing. Police learned that Eva had been seen climbing in a window of her husband’s home just before the New Year’s Eve explosion. The gas meter showed signs of tampering, and the ensuing fire was reported and filed under “Suspicion of Arson.” His attorney confirmed that Keller feared his wife was trying to hurt him.

As an alibi, Eva claimed that she had been at the movies. But the feature she named was shown only in the daytime. Without sufficient evidence to bring charges, police kept tabs on Eva. In May, she brought to the sheriff’s office two handwritten pages she said she found at Keller’s Wilmar bungalow. The first was a will in which Keller revoked his earlier changes and left everything to Eva. The second was a note in which Keller complained that an unnamed business enemy had threatened to kill him. A handwriting expert identified the note and the will as Eva Keller’s work.

Marrying sixteen months after the killing, Keller mortgaged her home furnishings and her car. She returned from a trip on Oct. 24, 1948, to find her home burned to the ground. When underwriters became suspicious of her insurance claim, an investigation by an arson specialist led officers to the insured goods, carefully stashed in another cabin. They also found a .38 Smith and Wesson which ballistics experts proved was the murder weapon. But the only witness who could identify the gun had been killed in an airline accident.

Tried for arson and found Guilty on May 3, 1949, Eva Keller was sentenced to twenty-two years at the Tehachapi Women’s Prison. In 1950, three years after Max Keller’s death, a woman who had spent a weekend with the Kellers positively identified the weapon as Eva Keller’s. Indicted for murder at last, Keller was found Guilty of first-degree murder in a non-jury trial by Judge Thomas L. Ambrose on Aug. 7, 1950, and sentenced to life in prison.

Kelley, William H., 1942- , U.S. On Oct. 3, 196, Charles Von Maxcy was stabbed and shot to death in his home in Sebring, Fla. The 42-year-old citrus and cattle millionaire was purported to have been involved in a love triangle with his 43-year-old wife, Irene, and 48-year-old John Sweet. Irene Maxcy and Sweet were accused of hiring two men to kill Charles Maxcy. On Nov. 8, 1968, in Bartow, Fla., Sweet was found Guilty of first-degree murder, largely on the testimony of Mrs. Maxcy, who was given immunity from prosecution. She said she had given Sweet $36,000 to arrange Maxcy's murder. Sweet was sentenced to life imprisonment, but the verdict was overturned three years later by an appellate court, and the prosecuting attorneys decided to drop the case.

Following Sweet’s release, Irene Maxcy was arraigned on a charge of perjury, and on Nov. 11, 1971, she was sentenced to life by Criminal Court Judge Alfonso C. Sepe in Miami. Mrs. Maxcy served four-and-a-half years of her sentence until she was paroled in 1978.

In June 1983, almost seventeen years after Maxcy’s murder, police arrested William H. Kelley in Tampa, Fla., and charged him with first-degree murder. He had been indicted by a grand jury two years earlier after prosecutors procured new evidence. John Sweet, given immunity from prosecution, said he paid a Boston bookmaker named Bennett, who in turn hired Kelley and Andrew Von Etter to commit the murder. The two were given $20,000 to divide, but Von Etter was found bludgeoned to death in a car in 1967, and Bennett mysteriously disappeared at the same time.

Kelley was defended by noted attorney William Kunstler. After a January 1984 mistrial, Kelley was found Guilty of first-degree murder on Mar. 30, 1984, in the Sebring, Fla., Circuit Courtroom of Judge Randolph Bentley. On Apr. 2, 1984, he was sentenced to death, and is currently on Death Row.

Kelly, Leo E., Jr., 1959- , U.S. In the early morning hours of Apr. 17, 1981, a 22-year-old University of Michigan student set off a firebomb in the dormitory where he lived, and then shot two fellow residents as they fled from the smoke and fire. Police went to the room of Leo E. Kelly, Jr., and arrested him. In Kelly’s room, they found the sawed-off shotgun used in the shootings, additional ammunition, a “zip gun,” and a list of students’ names with the name of one of the slain students highlighted. Both students, 19-year-old Edward R. Siwik and 21-year-old Douglas C. McGreaham died of their wounds shortly after the attack.

Kelly, a psychology student, claimed to have been under the influence of pills prescribed for an emotional problem at the time of the shooting, and he denied having any recollection of the shootings. Kelly was brought to trial on two counts of first-degree murder and was convicted on June 21, 1982. His crimes carried a mandatory life sentence. Kelly tried to appeal the conviction on the grounds of racial bias (Kelly is black; the men he killed were white, as was the jury that convicted him), but the attempts have been unsuccessful.

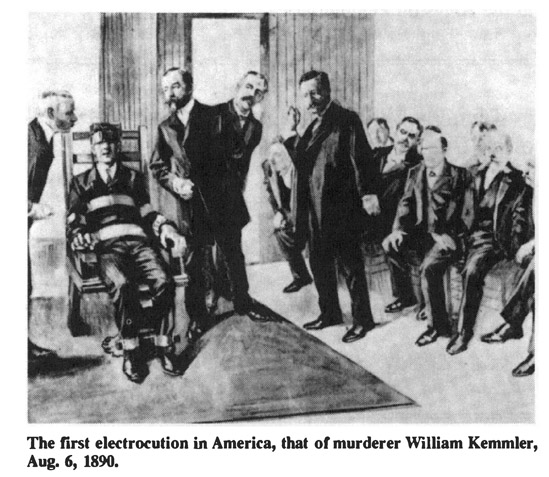

Kemmler, William Francis, 1861-90, U.S. The first man to die in the electric chair, William Kemmler was convicted of murdering his mistress, Tillie Zeigler, of Buffalo on Mar. 29, 1889, with a hatchet. The recently built electric chair was still experimental at the time. At the appointed hour on Aug. 6, 1890, Warden Charles F. Durston led the condemned man into the room. Kemmler was strapped into the chair and electrodes were fastened to his back and head. A portion of his shirt had been torn away in the rear to accommodate the lower electrode. “Don’t get excited Joe, I want you to make a good job of this,” Kemmler cautioned the deputy sheriff, Joseph Veiling.

A mask was placed over his head and 1,000 volts of electricity were activated by an executioner in an adjoining room. The switch stayed on for a full seventeen seconds, but it was not enough to kill Kemmler: he exhibited definite signs of life. The executioner threw the lever a second time, and this proved effective. Most of the press called the invention inhuman torture. Only the New York Times disagreed, saying it “would be absurd to talk of abandoning the law and going back to the barbarism of hanging.”

Kemper, Edmund Emil III (AKA: Big Ed; The Coed Killer), 1948- , U.S. Edmund Kemper’s sadism manifested itself at an early age. Soon after mutilating his sister’s doll, he tortured and killed the family cat. The oversized youngster caused his divorced mother so much trouble she sent him at fifteen to live with his grandparents. The next year, on Aug. 27, 1964, Kemper shot his grandmother in the back of the head with a .22-caliber rifle and then fired two more shots into her as she lay on the floor. Kemper shot and killed his grandfather when he returned, and locked his body in the garage. Kemper then called his mother and told her what he had done, explaining, “I just wondered how it would feel to shoot Grandma.” His mother told him to call the police, which he did, and waited for them on his grandparents’ porch. Kemper was committed to the Atascadero State Hospital. The California Youth Authority’s file on Kemper contained a psychiatric recommendation that he never be released into his mother’s custody, but in 1969 the Authority did exactly that. Kemper was not twenty years old, but already was six feet, nine inches tall, and weighed 280 pounds.

Clarnell Kemper worked as a secretary at the University of California in Santa Cruz. When Edmund moved in with her, she got him a university parking sticker so he could park on campus. This would later prove a valuable tool with which to lure coeds into his car. Kemper learned every back road of the local highway system and rigged his car so that the door on the passenger side could not be opened from inside. In 1971, he left his mother’s home and moved to San Francisco, where he began “practicing” getting victims into his car.

On May 7, 1972, he picked up two young hitchhikers from Fresno State College: Anita Luchese and Mary Anne Pesce. He assaulted them with a knife, but was surprised to discover that real killing was different from the television or movie version. He panicked and found himself standing outside the locked car. Incredibly, Pesce let him back inside. After Kemper had killed them, he disposed of the torsos in the Santa Cruz Mountains, but kept their heads in his room as a souvenir. He methodically searched for new victims, and found Aiko Koo, who was hitchhiking to her dance class in San Francisco.

The act of decapitation excited Kemper sexually. Sometimes he had sex with the headless bodies he brought back to his apartment, but soon disposed of the torsos, often after eating part of the flesh. He kept the heads of his victims, however, and even buried one in his yard, facing his bedroom, so he could talk to it at night. From the television show Police Story, Kemper picked up useful tips on how to avoid detection. Sometimes he met and chatted with homicide detectives at their favorite haunts to check on the progress of the investigation. The so-called “Coed Killer” killed six women in all, and police were stumped.

Kemper began to fear he would commit a murder so blatant that he would be caught. On Easter Sunday 1973, he entered his mother’s bedroom as she slept and bludgeoned her to death with a hammer. He then decapitated her and removed her larynx, which he threw into a garbage disposal. He called his mother’s best friend, Sara Hallet, and invited her for diner. When she arrived, Kemper strangled her and, again, cut off the head of his victim. He then rented a car and drove to Pueblo, Colo., to await the massive manhunt he was sure would follow. When his crime was still undetected three days later, he called Santa Cruz police and confessed, having to repeat his story several times before he was believed. Kemper was arrested, returned to California and, in April 1973, arraigned on eight counts of first-degree murder. Though he asked for the death penalty, he was sentenced to life in Folsom Prison.

Kendall, Arthur James, 1910- , Can. Arthur Kendall and his wife Helen lived with their five children in southern Ontario, Canada, in Elma Township. Kendall sharecropped, but on a trip near Tobermory in May 1952, he met a mill owner who offered him work.

On May 26, the 42-year-old Kendall began work at the mill, agreeing to remain until September, and stayed with three other workers in a cabin on the Bruce Peninsula on Lake Huron. During this time, he dated redheaded Beatrice Hogue, a waitress who lived in Wiarton with her seven children and whose husband was sailing on the Great Lakes. Kendall’s 33-year-old wife and his children later joined the workers during the summer. The men described Helen Kendall as a good housekeeper and cook, pleasant, and devoted to her children. On July 26, the last two mill workers left the cabin for the season, riding with Kendall to Wiarton where he picked up Hogue and six of her children. After letting the two men out, he drove the Hogues to the Kendall farm.

The next week Kendall returned to the cabin where his wife and children had remained. In the early dawn of Aug. 2, three of the Kendall children heard their mother cry, “No, Art, please don’t,” and saw him get up from a lower bunk and lay a butcher knife on the table. They watched him as he carried her body across the room and out the door. When he came back about half an hour later he cleaned up the blood and called the children to get up. He told one of the girls what to say if anyone inquired about their mother, then, later in the day, took the children to live at the Kendall house with the Hogues, telling police and neighbors his wife had left him.

In the years following, Hogue divorced her husband and married Kendall. In 1953, his children were taken away from him but he regained custody. Afraid of their father, the children finally spoke up nearly ten years after the murder. Kendall was arrested on Jan. 27, 1961. Police found blood stains still on the cabin floor and on pillows, and after a thorough search, police speculated that Kendall had put his wife’s body in Lake Scugog, located near the mill. Kendall was tried, convicted, and given the death penalty. His sentence was later commuted to a life term in the Kingston Penitentiary.

Kennedy, William Henry, See: Browne, Frederick Guy.

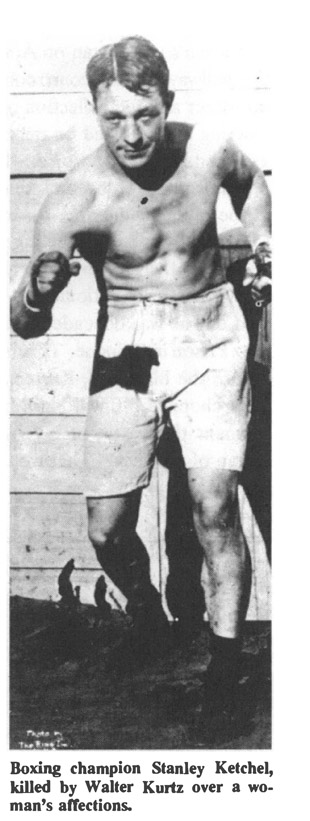

Ketchel, Stanley, See: Kurtz, Walter A.

Kid McCoy, See: Selby, Norman.

Kilpatrick, Andrew Gordon, 1920 - , and Hill, Russell William, 1931 - , Aus. On Aug. 1, 1953, a diver recovered a decapitated body from the Barwon River near the Princes Bridge in Geelong, Aus. The torso was stuffed into two sacks and tied to a 126-pound boulder. The victim’s head and hands, which had been severed with a hacksaw, were discovered an hour later underwater in a kerosene tin.

Colac, located 100 miles inland from Geelong, was hit hard by a series of robberies in Summer 1953 and Detective Sergeant Fred Adam, a member of Victoria’s Homicide Squad, was dispatched to Colac. While investigating an assault case, Adam thought that suspects Andrew Gordon Kilpatrick and Russell William Hill might be connected to the crimes. Notifying the local authorities of his suspicions, Adam was told to take on the case himself. Adam finally caught up with Hill, who had skipped bail, in late July in Hamilton, where he had been arrested on a vagrancy charge.

On July 30, Hill broke down and told Adam where he could find the body of 22-year-old Donald Brooke Maxfield. The gruesome discovery of Hill’s former accomplice was made in the Barwon River the next day. Hill informed police that Kilpatrick, a 33-year-old welder, had carried out the murder and dismemberment because Maxfield had talked too much about the trio’s criminal activity. When Kilpatrick was finally arrested, he refused to talk, but when faced with Hill’s accusation, he said the 22-year-old William Hill was as responsible for the crime as he was.

The trial began in October, with each man accusing the other of murder. Hill testified that only days after the slaying, Kilpatrick had stopped at the Princes Bridge on the way to Melbourne and forced him to help sink the body. Kilpatrick contended he was home in bed on the night of the murder. A key prosecution witness was taxi driver Maxwell George Benson. Benson told the Geelong courtroom that about three weeks after Maxfield’s disappearance, he had driven Hill, Kilpatrick, and two other men to Melbourne. On the way to the capital, Benson said Kilpatrick told him to stop near the Princes Bridge, where the men went under the bridge for about ten minutes.

After three hours of deliberation, the jury found both Kilpatrick and Hill Guilty of murder and they were sentenced to death by Mr. Justice Martin. The sentences were never carried out; Will’s sentence was commuted to twenty years in jail, and Kilpatrick’s to life. He was later released from jail in August 1976.

King, Alvin Lee, III, 1934-82, U.S. Alvin Lee King III majored in education at North Texas State University where he met his wife Gretchen Gaines. The couple was married in 1956. Ten years later, King taught math at Dangerfield High School in Dangerfield, Texas, until 1972 when he resigned. King’s legal troubles began in October 1979 with a warrant for his arrest following an allegation of incest by his 19-year-old daughter Cynthia King. After a change of venue to Sulphur Springs, the trial was set to begin on June 23, 1980. King never faced trial, because the day before he killed five people—he had already accidentally killed his father in 1966 when he dropped a loaded twelve-gauge shotgun in his parents’ Corpus Christi home—and seriously wounded ten others in a crowded church.

At 9 a.m. on June 22, King tied up his wife, loaded his pickup truck with more than 240 rounds of ammunition, an M-1 automatic carbine with bayonet, an AR-15 automatic rifle with scope and bayonet, a .38-caliber and a .22-caliber revolver, two bullet-proof flak jackets, and a WWII combat helmet. He drove to the First Baptist Church in Dangerfield and carrying his small arsenal he walked into the church where more than 300 parishioners were attending Sunday service. King burst in the sanctuary doors, shouted, “This is war,” and opened fire with the carbine, discharging five rounds in less than ten seconds. Killed by the first round were 7-year-old Gina Linam, whose skull was shattered as bullets riddled her head; 49-year-old Gene Gandy, whose wound just below the heart would keep her alive until late into the night, and 78-year-old Thelma Robinson.

Chris Hall, who helped operate the radio broadcast of each sermon, dove at King, who outweighed the younger man by some seventy pounds, and pushed him out into the lobby, knocking both automatic rifles from King’s hands, the helmet from his head, and his glasses from his eyes. If those glasses, which King needed to see anything more than six feet away, had stayed on, Hall may not have been able to scramble down the steps to the church basement, evading two shots from the .38-caliber revolver.

James Y. “Red” McDaniel, fifty-three, and 49-year-old city councilman Kenneth Truitt were the next heroes. McDaniel wrapped his arms around King and charged him out the front door, which broke as the two fell onto the front steps. King fired his .38 at McDaniel until the older man rolled off the gunman dead. He then shot and killed Truitt who dove at him while he still lay on his back. Inside the church, Larry Cowan picked up the carbine and ran after King, who dropped the revolver and fled. At a nearby fire station, King shot himself in the head with the .22 but failed to take his own life.

On July 11, King was charged with five counts of murder and ten counts of assault with intent to kill. Seventeen days later, a jury judged him incompetent to stand trial and sent him to Rusk State Hospital for the criminally insane until he was determined to be of sound mind. Although less than a month after the shooting King’s IQ was determined to be 151, Dr. James Hunter did not find him ready for trial until Nov. 24, 1981. King’s trial before Judge B.D. Moye on Jan. 25, 1982, never took place. During the hearing for a change of venue request by defense attorney Dick DeGuerin, King was held in the Dangerfield jail. On Jan. 19, 1982, he tied together strips he had torn from a towel, fashioned the strips into a noose, and hanged himself from the jail cell crossbar.

Kinman, Donald, 1923-1958, U.S. Details in the deaths of Ferne Redd Wessel, forty-three, and Mary Louise Tardy, twenty-eight, were remarkably similar, leading California police in Los Angeles and Sylmar to combine evidence and forces. The result was a double murder conviction against 36-year-old Donald Kinman. Before sentencing, Kinman said to the judge, “I guess I should get the gas chamber. I think I have it coming, don’t you?”

Wessel had been raped, and strangled, and found lying in a Los Angeles hotel bedroom the morning after Easter in 1958. She last had been seen on Easter, drunk, being helped to her room by a man she called “Don.”

Late in the afternoon on Nov. 22, 1959, Tardy’s body was found in a trailer in Sylmar, a trailer owned by Chester Baker but rented by Kinman. Several days before her body was discovered Tardy had been seen fighting with and then leaving her boyfriend. Later she was seen at a bar with a stocky, curly-haired man she called “Donald.” That description fit Kinman. As in the Wessel murder, Tardy had been strangled and raped after being partly suffocated by a pillow, and her clothes had been dumped on top of her body. Fingerprints taken at both scenes were identical. On Dec. 2, Kinman turned himself in, confessing to the Tardy murder. “I don’t know what came over me, but it just seemed like something I had to do,” he said, adding that he had finally surrendered because “my conscience has been bothering me.” When presented with overwhelming incriminating evidence, Kinman confessed to having killed Wessel as well.

Kinne, Sharon, 1941- , U.S.-Mex. On the night of Mar. 19, 1960, police arrived at the home of James A. Kinne, an electronics engineer who lived just outside Kansas City, Kan., to find the man dead on the floor, with his wife, Sharon, and their 2-year-old daughter nearby. Sharon Kinne explained that her daughter was playing with her husband’s .22-caliber handgun when it accidentally discharged. Her story was accepted—friends testified that the child occasionally played with guns–and the shooting was ruled accidental.

With her insurance settlement, Kinne bought a new Thunderbird. She began spending time with the salesman who had sold her the car, but eventually aroused the suspicions of the salesman’s wife, Patricia Jones. On May 26, 1960, friends of Jones told police that they had seen her climb into a Thunderbird with a dark-haired woman, who turned out to be Kinne. The next night Jones’ bullet-riddled body was found in a lover’s lane in Jackson County. Based on the many coincidences, a murder indictment was returned against Kinne in September 1960. When the bullets that killed Jones, however, were compared with shells known to have held bullets from James Kinne’s .22-caliber handgun, it was revealed that his gun could not have been used to kill Jones. Kinne was acquitted.

Meanwhile, however, witnesses had since come forward to testify that Kinne had put a $1,000 contract out on her husband, and ballistics experts had declared it impossible that a 2-year-old had pulled the trigger on a heavy gun like a .22-caliber handgun. Kinne was found Guilty of killing her husband and sentenced to life in prison.

The verdict was challenged on a legal technicality, and a mistrial was declared. There was yet another mistrial before the case was heard again. This time Kinne was freed after the jury failed to agree on a verdict. Flushed with her success, she traveled to Mexico City, where she met radio announcer Francisco Paredes Ordonez in a bar on Sept. 18, 1964. He went with Kinne to her room. Soon, a motel desk clerk heard shots ring out from the room. Upon investigation, he found Kinne on the floor struggling for control of a gun—finally shooting Ordonez. When the motel owner tried to intervene, she shot him too.

A Kansas City prosecutor arrived to examine the gun and determined that the gun that had been used to kill Ordonez was the same gun that had been used to shoot Jones. It did not matter though, as Kinne could not be tried for Jones’ murder again. In October 1965, Kinne was sentenced to ten years in jail in Mexico for killing Ordonez. She appealed, and the courts added three more years to her sentence.

Kinney, David, prom. 1970, U.S. On June 1, 1970, in Temple Terrace, Fla., the Reverend Jerry C. Monroe, ostensibly out ministering to parishioners, instead picked up drug-crazed David Kinney across from a bus depot, took him to a bar where he bought beers, drove him to a dump, performed a homosexual act on him, and then was murdered by Kinney. Kinney, who said he was “high” at the time of the shooting and did not know why he did it, will spend the rest of his life in prison.

The news, revealed in court testimony after Monroe’s death, of the priest’s other life, shocked his widow and congregation at St. Catherine’s Episcopal Church. The first inkling Monroe’s wife had that there was something about her husband she knew nothing about came when police called two weeks after his disappearance, saying they had found her husband’s decayed body under a refrigerator in the city dump. The pastor had died of two .38-caliber gunshot wounds in the lower chest and abdomen.

After hearing of his death, workers for a local roofing company reported that one of their co-workers had bragged that he had killed a man. Police soon tracked down Kinney, a young man who earlier claimed to have slept through the shooting incident. They found a .38-caliber Victor revolver in his room that matched ballistically with the bullets taken from the priest’s body.

Kinney had no choice but to confess. He made one feeble attempt at a lighter sentence, saying he had been “high” that night on two “Purple Wedges,” a form of LSD. The jury said that was no excuse for murder and sentenced Kinney to life in prison.

Kiss, Bela (AKA: Mr. Hoffmann), b.1872, Hung. When Bela Kiss of Czinkota, Hungary, learned that his 25-year-old wife, Maria, was having an affair with Paul Bihari, he immediately ordered several enormous metal drums–for gasoline storage he said. It was February 1912, and a war loomed. Gas would soon be in short supply. Bihari and Maria then mysteriously disappeared, and Kiss said they had run off together.

His housekeeper, Mrs. Kalman, noted with growing alarm the number of female visitors coming to his house. At the same time, more metal drums began arriving-for the war effort, Kiss reiterated. The Budapest police were alerted to the disappearance of two widows whose names were Schmeidak and Varga, who, at last report, had visited the Budapest apartment of Mr. Hoffmann. Their whereabouts were not accounted for until much later.

In November 1914 Kiss was drafted into the army and sent to the front in Serbia. Nearly two years later, in May 1916, Constable Trauber received word from the military that Kiss had died in a military hospital in Belgrade. Recalling his earlier words about the gasoline he had hoarded at his home, Trauber dispatched soldiers to Czinkota for the fuel. Seven drums were found, each containing the body of a woman who had been garrotted. Letters written to Kiss were found in his personal belongings. It was clear that he had lured the victims to his home through advertisements placed in the newspaper under the name of Professor Hoffmann, Poste Restante, Vienna, who promised companionship and marriage. What these unfortunate women encountered instead was a madman interested only in acquiring their cash and jewels. A search of the countryside turned up seventeen more drums. Found inside two of them were the unfaithful wife and her lover Paul Bihari.

In 1919, Kiss was seen in Hungary. It was learned that he switched tags with a fallen comrade on the battlefield and had assumed a new identity. A man matching the description of Kiss was seen in New York in 1932. The individual was observed exiting the Times Square Subway Station by Detective Henry Oswald of the homicide squad. He quickly disappeared into the crowd.

Knight, Virgil, 1961-87, U.S. When a newly divorced man learned he lost a custody battle and would not have the right to care for his two small children, he killed them, along with his ex-wife, two neighbors, and himself.

Virgil Knight, twenty-six, took six lives on Dec. 14, 1987, one week after his divorce was final. Using a small-caliber pistol, the Oklahoma man in a jealous rage gunned down his 26-year-old ex-wife, Deetta Knight, as she lay in her bed, his 6-year-old son, Curtis Knight, his 2-year-old son, Kevin Knight, his 23-year-old former sister-in-law, Carrie, and a next-door neighbor. He then turned the gun on himself. Twin 18-year-old brothers of Knight’s former wife escaped from the duplex. They confirmed that Knight was the assailant. Knight’s mother said he had been depressed for days.

Knighten, Greg, 1972- , U.S. Greg Knighten, sixteen, was convicted of murder on Oct. 23, 1987, in the brutal slaying of undercover police officer George Raffield. The 21-year-old officer was posing as a Midlothian, Texas, High School student for an undercover investigation to identify drug users in the school. The officer’s identity was revealed before any arrests were made. After a Friday night football game, Raffield failed to call in his daily report. Police found his body the next day and hours later arrested Richard Goeglein, seventeen, Jonathon Jobe, sixteen, and Knighten, the son of a Dallas police officer. Cynthia Fedrick, twenty-three, was charged with soliciting the murder. Raffield had been shot in the back of the head, allegedly by the .38-caliber revolver that belonged to Knighten’s father.

If Knighten had been charged with capital murder he would have automatically received a life sentence. Because he was only sixteen the death sentence was not an option. Instead, the jury sentenced the youth to forty-five years in prison.

Knowles, Dr. Benjamin, prom. 1920s, w. Afri. Without a jury trial a husband was accused, convicted, and sentenced to die for murdering his wife, though before she died his wife emphatically told the police the incident was an accident.

Dr. Benjamin Knowles lived in Bekwail, in the colony of Ashanti, W. Afri., with his wife, the former Madge Clifton, and he was the medical officer of health for the area. The couple occasionally quarreled and Knowles frequently drank. Also, Knowles kept a revolver loaded and cocked beside his bed to protect his wife and himself from housebreakers.

On the evening of Oct. 20, 1928, Mrs. Knowles was preparing for bed after a dinner party. Dr. Knowles already was in bed when she accidentally sat down on the revolver lying on a chair beside the bed. When she stood up to move the gun somewhere else, the trigger caught in the lace of her nightgown, causing the gun to discharge. Mrs. Knowles was shot in the left buttock with the .45-caliber soft-nosed bullet which exited above her right hip. The wound was serious and demanded surgery yet Dr. Knowles simply sterilized, dressed, and plugged the wound and then gave them both sedatives.

District Commissioner Mangin was notified that a gun was fired inside the Knowles’s bungalow and investigated that night. Dr. Knowles told him that while there had been a slight domestic quarrel, everything was under control. Mangin returned the next day with the surgeon Dr. Howard Gush who, upon examining Mrs. Knowles, took her immediately to the hospital. It was too late for surgery. Two hours before she died Mrs. Knowles told police and Mr. Mangin that the shooting had been an accident and even detailed the events. When she learned her husband was under suspicion, she was surprised and repeated as emphatically as she could in her weak condition that the shooting was an accident.

The police chose to believe otherwise and arrested Dr. Knowles who then was quickly tried in November without a jury. The commissioner of police prosecuted the case and Knowles defended himself. The prosecution was very shaky, being based on a theory the police developed on two bullet holes in the bedroom which they claimed were aligned. According to this theory, when Dr. Knowles shot his wife, the soft-nosed bullet passed through his wife, a tabletop, and a heavy wardrobe door. Aside from the implausibility of a .45-caliber soft-nosed bullet passing through three objects, a house servant had picked up a spent bullet next to the chair where Mrs. Knowles was shot, and a neighbor testified that the bullet hole in the wardrobe was old.

Nevertheless, Knowles was found Guilty and sentenced to die. Sir A.R. Slater, governor of the Gold Coast, commuted the sentence to life in prison and Knowles was transported to London where he appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. There, his sentence was quashed because a ruling of manslaughter had not been considered in his initial trial. Dr. Knowles died in London three years later.

Knowles, Paul John, 1946-74, U.S. A petty thief went on a rape and murder spree, killing eighteen people in a four-month period before police caught him.

Paul Knowles, a small-time thief, spent half of every year between 1965 and 1972 behind bars. While serving a longer sentence in Raiford Penitentiary in Florida he corresponded with Angela Covic, who eventually agreed to marry him. After finding a lawyer, securing his parole, and flying him to San Francisco, Covic decided not to marry Knowles because he made her uneasy. She sent him back to Jacksonville, Fla., where he got in a bar fight and was locked up at the police station. He picked the lock on July 26, 1974, and escaped.

The night of his escape Knowles broke into the home of Alice Curtis, bound and gagged her, and stole her money and car. Curtis died that night from the gag stuffed too far down her throat. A few days later, Knowles abducted two friends of his family, Mylette Anderson, seven, and her sister Lillian, eleven, and killed them because they recognized him. He drove to Atlanta Beach where he strangled Marjorie Howe in her home and stole her television. A few days later, he picked up a female hitchhiker whom he raped and killed. The body was never identified. On Aug. 23, in Musella, he strangled Kathie Pierce in her home while her 3-year-old son watched. Less than two weeks later, Knowles met William Bates in Ohio whose nude and strangled body was found in the woods a month later. He then shot and killed an elderly couple in their camping trailer in Ely, Nev. On Sept. 21, he raped and throttled a woman he accosted beside the road.

Knowles met Ann Dawson two days later in Birmingham, Ala. They liked each other and traveled together for six days, spending her money. While her body was never found, Knowles later confessed to killing her. He then drove to Connecticut where he knocked on the door of a house in Marlborough. When teenager Dawn Wine answered, Knowles forced himself inside and ordered her to her bedroom where he raped her for an hour. When the mother, Karen Wine, came home, Knowles forced her to cook him a meal and then took her upstairs where he made mother and daughter strip, bound their hands, raped the mother, and strangled them both with a nylon stocking. On Oct. 19 at a house in Virginia, he demanded a gun from Doris Hovey and she gave him a .22-caliber rifle from her husband’s gun cabinet which he loaded and used to shoot her in the head. He then wiped the gun clean and left it in the house without taking anything.

Knowles contacted his attorney in Miami, telling him he wanted to confess to fourteen murders. While his lawyer could not persuade him to turn himself in, Knowles did agree to tape a confession. His lawyer, Sheldon Yavitz, notified police, but by the time they responded Knowles had already left Miami.

He then stabbed Carswell Carr repeatedly and strangled his 15-year-old daughter. Carr, whom he met at a gay bar, had taken Knowles home to spend the night. On Nov. 8, Knowles met Sandy Fawkes, a journalist. Fawkes and Knowles became lovers and she later wrote of her few days with him in her book Killing Time. She thought him sexually inexperienced and said he often acted as a tender, protective husband. He did not harm Fawkes but did attempt to rape a friend of hers, Susan MacKenzie. She escaped and Knowles left town the same day. He drove to Key West, Fla., where he took Barbara Tucker hostage and left her tied up in a motel room while he drove off in her Volkswagen. Police were notified of the stolen Volkswagen and Patrolman Campbell spotted the car and pulled Knowles over. Knowles took him hostage at gunpoint and hijacked the patrol car. He then overtook businessman James Meyer, handcuffed him, and drove off in a new car with his two hostages. A few hours later he handcuffed the two men to a tree and shot each in the back of the head.

On Nov. 17, 1974, when Knowles attempted to break through a police roadblock his car skidded and crashed into a tree. On foot, with 200 police chasing him, Knowles was apprehended by Terry Clark, a young man who ran after Knowles with only a shotgun. The following day, Knowles was shot and killed by FBI agent Ron Angel as he was being transported to a jail when he picked his handcuffs and attempted to take a sheriffs revolver.

Kogut, William, d.1930, U.S. When William Kogut received the death sentence in 1930 for killing a woman with a pocketknife, he told the judge that no one would ever execute him. Therefore, prison officials were careful to keep all potential tools of suicide away from Kogut.

Yet, unknown to the guards, Kogut had removed the red spots from the hearts and diamonds of a deck of cards. The spots contained nitrate and cellulose—ingredients used in the manufacture of explosives. Putting the spots in a pipe and soaking it in water, Kogut made a bomb which, on Oct. 9, he placed on the hot oil heater in his cell at San Quentin Prison. He laid his head on top of the bomb and waited. The bomb worked. One story tells of the doctor who performed the autopsy picking the ace of hearts out of Kogut’s skull.

Kopsch, Alfred Arthur, prom. 1925, Brit. Alfred Kopsch was a sensitive young boy who lived with his parents in Highbury, north London. When he was fourteen, his uncle, Arthur Walter Thornton, and his new wife moved in with the Kopsch family. Thornton’s wife, Beryl Lilian Thornton was only a few years older than Alfred. Alfred was infatuated with Beryl and over the next four years they became lovers.

When Alfred was eighteen Beryl told him she was pregnant and he was the father. She asked Alfred to kill her. On Sept. 15, 1925, the two lovers went into Ken Wood. There, Beryl asked Alfred again to kill her. The next day Alfred turned himself into the police, stating: “We lay down by the side of a tree and she asked me to strangle her while she was asleep. At 2 a.m. I thought she was asleep. I put my thumb on her neck and tied my necktie round her neck. I then covered her with my overcoat.”

At his trial in October with Justice Branson, the counsel for the defense based its case on “irresistible impulse,” that Alfred’s act was an unconscious one urged on by Beryl’s insistence that he kill her. The jury found him Guilty and while it recommended mercy, Alfred was sentenced to death. A few weeks later he gained a reprieve.

Koslow, Jack, 1936- , U.S. Jack Koslow was the leader of a group of four youths (including himself) who engaged in what the press called “thrill” violence. In August 1954, they beat, horsewhipped, set on fire, and drowned a number of old men who lived on the Brooklyn streets. Eventually arrested by two police officers walking a beat, they were charged with the murder of an old man they dragged seven blocks and threw in the East River where he drowned. One youth turned state’s evidence against his friends while the indictment was dismissed for another. The two remaining youths, Koslow, eighteen, and his 17-year-old cohort, were found Guilty of felony murder as the man died while being kidnapped. Both received life sentences.

Kroll, Joachim (AKA: The Ruhr Hunter), 1933- , Ger. West German murderer-rapist Joachim Kroll began acting out murderous sexual fantasies in 1955 although his crimes did not specifically distinguish themselves to police until 1959. When arrested in 1976, Kroll, called a mental defective by authorities, told police that he committed his first rape-murder in February 1955 near the village of Walstedde. He attacked 19-year-old Irmgard Strehl and raped her apparently after knocking her unconscious. In June 1955, Klara Tesmer’s body was discovered in the woods near Rheinhausen, some distance from where Kroll’s first victim had been found but still within the Ruhr area where all of his crimes were committed. She, too, had been raped while unconscious.

Kroll continued raping and killing girls and women. Beginning in 1959, however, he began adding another gruesome detail to his crimes. In July 1959, police found the body of 16-year-old Manuela Knodt, strangled and then raped. Her murderer-—Kroll, as it turned out–had also taken slices from her buttocks and thighs, cuts made in such a way that police concluded they were intended to be eaten. Kroll continued to rape, murder, and butcher. His victims included 13-year-old Petra Giese in the village of Rees on Apr. 23, 1962, and 13-year-old Monika Tafel in nearby Walsum on June 4, 1962. On Dec. 22, 1966, he strangled and raped 5-year-old Ilona Harke, cutting flesh from her shoulders and buttocks.

Kroll was nearly caught on a number of occasions. In Allgust 1965 he became sexually excited watching a young couple having sex in the front seat of a car. When he punctured the car’s front tire with a knife, the man began to drive away, but when Kroll flagged him down, he stopped and got out of the car. Kroll stabbed him but was driven off when the woman tried to run him down with the car. The man died several days later of the stab wounds. On another occasion in 1967, Kroll lured a girl into a meadow and showed her a book of pornographic photographs. The child recoiled in horror and ran away before Kroll could strangle her. Nine years later when Kroll named her in his lengthy confessions, police located her and she confirmed the story although she had never reported it at the time.

In 1976, Kroll killed 4-year-old Marion Ketter. Police made door-to-door inquiries to find the child and were told by one resident of the area that his neighbor, a lavatory attendant, had just told him not to use a particular lavatory in their building because it was stopped up with “guts.” The toilet was in fact blocked with the internal organs of a child. In Kroll’s apartment, police found plastic bags of human flesh in the freezer and, cooking on the stove, a “stew” which contained a child’s hand.

Once apprehended, Kroll readily confessed. His memory was poor, but he was able to recall fourteen victims over a twenty-two year span. He also talked freely to police about his sexual habits. As a young man he was too self-conscious to have sex with a conscious woman which explained his habit of rendering his victims either unconscious or dead before raping them. Kroll had strangled plastic dolls during sex before he graduated to living victims. Kroll claimed that he had taken flesh from the most tender-looking victims to save money on meat.

Kubiczek, Jose, d.1984, Fr. Jose Kubiczek, recently divorced from his wife, strangled her when she went to their Saint-Amand-les-Eaux home on Aug. 27, 1984, to take custody of their only son. Kubiczek dressed the corpse in a wedding gown, lay down on the bed next to her, and took his own life.

Kulak, Frank, 1928- , U.S. Frank Kulak, a WWII and Korean War veteran, and recipient of the Purple Heart, held more than 100 Chicago policemen at bay from his South Side apartment on Apr. 14, 1969, after officers questioned him about a series of bombings that had plagued the neighborhood for several weeks. To show the public what the Vietnam War was really like, Kulak embarked on a self-appointed mission of blowing up war toys in department stores, explaining to police that it was necessary to alert the public to the threat of Chinese Communism.

When Chicago bomb squad officers Sergeant James Schaffer and Detective Jerome A. Stubig arrived at Kulak’s home, Kulak reached into an arsenal of weapons that included an M-1 rifle, automatic pistols, 2,000 rounds of ammunition, twenty-five pounds of explosives, and several homemade pipe bombs, and threw a grenade at the two men standing on his wooden back porch. The porch splintered in the explosion, and the officers were blown to the ground. Kulak then riddled their dying bodies with machine-gun fire. He began heaving bombs from his window to the street and started randomly firing at pedestrians who scrambled for cover. Soon afterward, more than 100 officers had assembled outside the building, and three hours later he surrendered.

Arrested on two counts of murder, Kulak confessed to the bombings. Found mentally unfit to stand trial, he was remanded into the custody of doctors at the psychiatric facility in the state prison at Chester, Ill. Kulak remained in the Chester prison until 1981. He was then brought back to Chicago to appear before Criminal Court Judge Frank B. Machala who was to decide whether to dismiss charges against him, in accordance with a new Illinois state law requiring the release of those prisoners incarcerated in a mental institution for a length of time equal to that which they would have been required to serve before becoming eligible for parole. Kulak had served eleven years at Chester, thus meeting the requirements of the law. Machala rendered his decision in January 1981 and sent Kulak back to jail, refusing to dismiss the charges against him.

Kummerlowe, Karl Kenneth, prom. 1970s, U.S. Karl Kenneth Kummerlowe, a graduate of Yale University, worked as an engineer at AiResearch manufacturing in Phoenix, Ariz., where he developed many items, including a portable field hospital that contained specially designed incinerators for the cremation of body parts. If Karl Kummerlowe had used this invention when he brutally murdered his lover’s husband, Harley Kimbro, he might never have been caught.

Kummerlowe was captured after Phoenix police officers, who were watching a parking lot for automobile burglars, noticed him dump the contents of his briefcase—a bloodstained shirt and towel, and ID cards belonging to Kim-bro-into the dumpster. When police stopped him and searched his truck, they found several dismembered body parts and the tools that Kummerlowe had used to cut Kimbro up. Kummerlowe killed Kimbro in the bathtub of a Phoenix motel after he had conned the man into the city by pretending to be interested in the home that Kimbro was selling. After searching area dumpsters, officers located almost half of Kimbro’s body. The remaining body parts were never located.

Kummerlowe pleaded not guilty maintaining that he had no knowledge of the murder, but Kimbro’s head found in the back of his pickup truck proved too damaging. Kummerlowe was sentenced to life in prison where two weeks later he attempted suicide by jumping over a second-story railing and crashing head first onto the concrete floor below. He severely injured his skull and paralyzed both an arm and a leg.