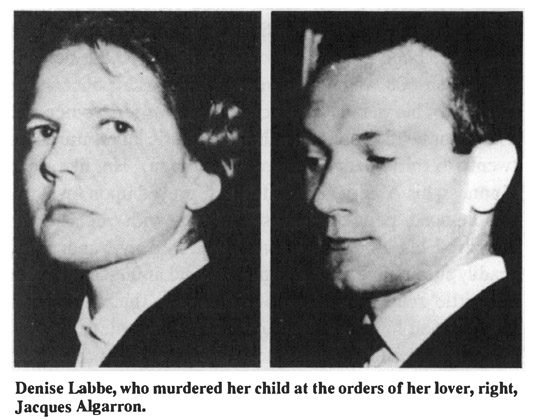

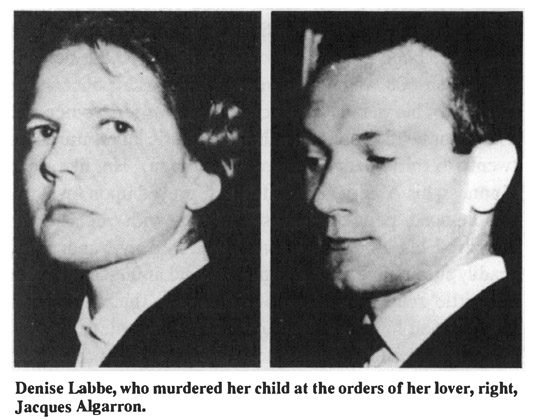

Labbe, Denise, c.1926- , and Algarron, Jacques, c.1930- , Fr. Denise Labbe was the daughter of a postman in the village of Melesse, near Rennes, Fr. After the Germans invaded in 1940, Denise’s father killed himself. She then diligently pursued her university studies at Rennes, and also worked as a secretary at the National Institute of Statistics there. She had numerous affairs and gave birth to a daughter named Catherine whom she left with her mother while she went to Paris to work for the Institute. There, she met 24-year-old Jacques Algarron, an officer cadet at the Saint-Cyr School and a devotee of Jean Paul Sartre and the Marquis de Sade. The intense, brooding Algarron had already fathered several illegitimate children of his own. “In the manner of Andre Gide,” he would say, “I offer you fervor.”

Algarron, who was himself born out of wedlock, compensated for his feelings of inadequacy by pretending to possess superhuman qualities. He tested Labbe’s devotion by ordering her to pick up strange men in the streets, and then take them back to the apartment she shared with him. Labbe made love to these men while Algarron hid in the closet. He then forced her to seek his forgiveness. “To merit my love, you must go from suffering to suffering,” he said. Algarron threatened to leave her unless she murdered two-and-a-half-year-old Catherine. He first broached the subject to her on Aug. 29, 1954.

Labbe obeyed. She tried to drop her daughter out a window, but a neighbor intervened. Then she threw Catherine into a canal, but a passerby rescued her in time. Then, on Nov. 8, 1954, Labbe drowned Catherine in a zinc washtub at her mother’s home in Rennes. “It takes courage to kill your own daughter,” beamed Algarron. Labbe confessed to the Rennes Police, describing her lover as a “cultist devil.” “You promised to marry me if I killed Cathy, but you threatened to abandon me if I did not kill her,” she sobbed. The pair were tried for murder at the Loiret-Cher Assizes in Blois on May 30, 1955. The jury returned a Guilty verdict but pleaded for mercy for Labbe, whom they believed Algarron had placed under a “spell.” She was sentenced to life imprisonment. Algarron received twenty years’ hard labor.

Lacroix, Georges (AKA: Roger Marcel Vernon; Mr. Georges), and Alexandre, Pierre Henri, prom. 1936, Brit. In the 1930s, London mobster Max Kassel, was known in the streets of Soho as “Max the Red” for his flame-colored hair. He was said to have immigrated from Latvia on a forged passport, but some insisted he was French-Canadian. Kassel was a drug trafficker and pimp with connections throughout Europe. In 1935, the 56-year-old Kassel was in debt, and his creditors were growing anxious, especially one who called himself Roger Vernon, but who was actually an escapee from Devil’s Island named Georges Lacroix. Lacroix, a pimp and a murderer, lived off his girlfriend Suzanne Bertron. Occasionally he arranged marriages for European women so they could stay in Britain. Bertron herself married an English seaman, William Naylor, to remain in the country and then abandoned him for Lacroix.

Lacroix had loaned Kassel £25 and was anxious to collect. Lacroix tried to collect at his apartment on Little Newport Street one night in January 1936. The two men quarrelled in Bertron’s presence, and Lacroix, feeling himself insulted, was even more determined. On Jan. 23, Lacroix summoned Kassel to Newport Street. Bertron’s maid, Marcelle Aubin, led Kassel upstairs, where Lacroix was waiting. The radio blared. From downstairs the maid strained to hear what was going on, but it was impossible. Suddenly she heard gunshots and a cry for help from Lacroix. Aubin ran upstairs, where she saw the two men struggling. Kassel had been shot, and was pleading for his life. He begged them to take him to the hospital, but they refused. “I’m going to die! Give me water,” he pleaded. Kassel made one last bolt for freedom, but was immediately captured and locked in the bathroom, where he died a few minutes later. Lacroix swore Aubin to secrecy and then telephoned his friend, Pierre Henri Alexandre, to ask his help in disposing of the body. He arrived around 4 a.m., and decided they should wrap the body in a rug and drive out of the city. They drove Alexandre’s Chrysler to the village of St. Albans and left the body by the side of the road. Henry Sayer, a local carpenter, discovered it five hours later.

Under Chief Inspector Frederick Dew Sharpe, Scotland Yard quickly learned the identity of the killers and issued warrants for their arrest, but Lacroix and Alexandre had fled to France. A legal dispute between the French and British governments made extradition impossible. The home secretary maintained that Lacroix was a British subject because he was Canadian-born. The French, on the other hand, insisted that Lacroix had escaped from Devil’s Island, and they maintained jurisdiction in the case. Lacroix and Bertron were tried for murder at the Assize de la Seine in April 1937. Bertron was acquitted by a sympathetic jury. Lacroix was found Guilty and sentenced to ten years at hard labor and twenty years exile from France. Alexandre received five years of penal servitude after trial in the British courts.

LaMarr, Harley, 1931-51, U.S. A mother’s simple request to her son carried with it a death sentence for a socially prominent Buffalo woman and her own son.

Harley LaMarr lived in a run-down section of Buffalo, N.Y., in 1950. On Jan. 8, 1950, his mother killed her second husband John Palwodzinski with a kitchen knife during a domestic quarrel in their apartment.

The 50-year-old mother pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to serve thirty years at the Bedford Hills Prison for Women. When LaMarr visited her in jail he asked if there was anything he could do. “Yes, bury Pa,” she said. This he agreed to do, but being jobless it was hard for him to pay for the funeral. He decided that the only sure way to bury his stepfather was to find someone to rob.

On Feb. 11, he set out to find a victim in the fashionable part of town, with an ancient hunting rifle that had been collecting dust under the eaves. He took public transportation to his destination with the gun hidden under his trench coat.

Lurking behind trees and bushes, LaMarr spotted his victim, Mrs. Willard Frisbee, wife of the sales manager for the Queen City Pure Water Company. LaMarr was most attracted to the flashy automobile she drove and her obvious wealth. Beyond that he knew nothing about her. At a stoplight, LaMarr bounded into the unlocked passenger side of her car and ordered the woman to keep driving. Frisbee, thirty-six, attempted to talk him out of his course of action and a struggle ensued, the woman apparently not frightened or intimidated. As she grappled with her abductor the gun accidentally discharged and she was killed.

The body was tossed in a ditch and young Harley discovered to his dismay that she had only $6. He ignored the fur coat and jewels. Police traced the bullets to a hardware store, and the identity of Harley LaMarr was established. He was arrested and confessed freely to the crime. On May 15, 1950, LaMarr was convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to death. He died in the electric chair at Sing Sing on Jan. 11, 1951, a little more than a year since his stepfather had been killed.

Lance, Myron, See: Kelbach, Walter.

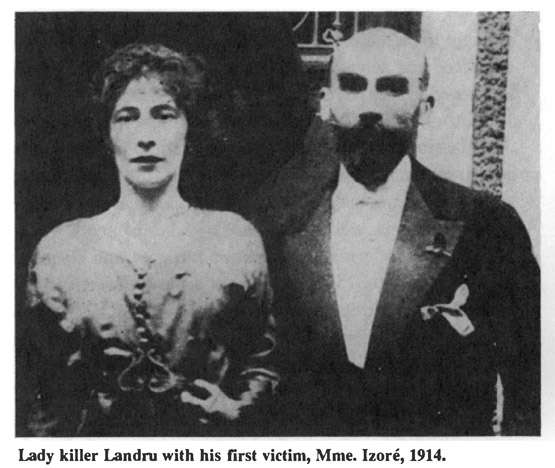

Landru, Henri Desire (AKA: Bluebeard; M. Diard; Georges Petit; M. Dupont; M. Cuchet; Lucien Guillet; M. Fremyet; M. Forest), 1869-1922, Fr. Henri Landru was a mass murderer, a lady killer whose repetitious slayings, except for the manner of disposal, were uninspired and must have been wearisome for him, if, indeed, he slew the more than 300 women estimated by French police. The number of his victims positively known was ten women and a boy, but in all probability, this systematic killer murdered twenty to thirty people, almost all women. He, like Belle Gunness, his American counterpart, preyed upon lovelorn, middle-aged people. Those women with means who answered his enticing ads were charmed by Landru and readily succumbed to his magnetism and animal craving for sex, little realizing that this passionate, thickly-bearded, bald-headed lothario was planning their murders.

Little in Landru’s childhood and early life foretold the monster to come. The Paris-born Landru was educated at Ecole des Freres and received good grades. He went on to study at the School of Mechanical Engineering and was then conscripted into the army, serving four years and reaching the rank of sergeant. In 1893, while still in the service, Landru began an affair with his cousin, Mlle. Remy. When she became pregnant with his child, Landru married the attractive young girl. Upon re-entering civilian life in 1894, he obtained a job where he had to provide a deposit against goods he was to sell. He never got the goods and his employer decamped to the U.S., taking Landru’s deposit with him. This so embittered the 24-year-old Landru that he decided to turn crook himself. He opened a secondhand furniture store in Paris but concentrated on swindling schemes.

Landru was not a successful confidence man. He was arrested four times between 1900 and 1908, receiving prison terms that ranged between two years and eighteen months, all for various frauds. Shortly before the outbreak of WWI in 1914, Landru, using many aliases, began placing advertisements in newspapers, addressing them to lonely women reading the lovelorn columns. Though he remained married and had by then fathered another three children, Landru, unknown to his wife, advertised himself as a well-to-do bachelor looking for “proper” female companionship. Landru maintained a separate address for the assignations that resulted in this lovelorn scheme. He apparently enticed the women answering his ads to his bachelor’s residence and, after promising marriage and obtaining their money from small savings accounts or deeds to parcels of land or buildings, he murdered them and disposed of their bodies. The first such victim was 40-year-old Mme. Izore, who vanished into Landru’s arms in 1914, along with her dowry of 15,000 francs.

By this time police were looking for Landru for swindling an elderly couple out of their savings. Landru had disappeared, however, and with the coming of the war was able to assume other identities. What launched Landru into a career of murdering for profit is uncertain. The war, with its awful devastation and utter unconcern for human life, may have altered his otherwise reasonable perspectives. It was also suggested that he turned to this most atrocious form of making a living since his family ties had been severed by the deaths of his mother and father. It is also safe to assume that Landru, having failed miserably at lesser illicit schemes to make a dishonest franc, felt that he had nothing to lose in his lovelorn murder schemes.

In late 1914, Mme. Cuchet, a 39-year-old widow with a 16-year-old son, answered one of Landru’s ads, thinking him to be M. Diard, a successful engineer. Falling in love with Landru, the woman informed her family that she intended to marry him and asked that her parents, sister, and brother-in-law visit the man of her dreams at a villa he kept in Chantilly. The family, unannounced, went to the villa but found Landru absent. The inquisitive brother-in-law looked through a chest and found it crammed with love letters from other women, who had been answering his dozens of lovelorn ads. The brother-in-law denounced Landru to Mme. Cuchet, but the woman would hear no criticism of him and she and her teenage son moved away from her family to a small villa in Vernouillet where Landru joined her. The woman and boy vanished a short time later, in January 1915, as did Diard-Landru.

Opening up new bank accounts, Landru deposited about 10,000 francs, claiming he had received an inheritance from his father. The bankers, had they checked, would have realized how unlikely this story was since Landru’s father was a common laborer who had worked in the Vulcain Ironworks. In June 1915, Landru met through his ads Mme. Laborde-Line, a widow from Buenos Aires who moved out of her Paris apartment, telling the concierge that she was going to live in a villa at Vernouillet with a “wonderful man.” She was seen picking flowers in Vernouillet on June 26, 1915, and was never seen again. Landru later sold her securities and moved Mme. Laborde-Line’s furniture to a ramshackle garage he kept at Neuilly which he called his used furniture store. From here he sold off his latest victim’s household goods one by one.

Mme. Guillin, a 51-year-old widow who had just converted some insurance policies to 22,000 francs, answered one of Landru’s ads on May 1, 1915, later visiting Landru at his villa in Vernouillet and then moving there to ostensibly become Landru’s bride on Aug. 2, 1915. She too vanished and on Aug. 4, Landru moved all the furniture from the Vernouillet villa to his Neuilly garage and later cashed some of Mme. Guillin’s securities. Late in 1915, Landru, using the alias George Petit, forged Mme. Guillin’s signature to certain bank documents in order to withdraw 12,000 francs from her account in the Banque de France. When questioned about his actions at the bank, Landru coolly explained that he was Mme. Guillin’s brother-in-law and that she could no longer conduct her own business affairs since she had suffered a stroke that left her paralyzed.

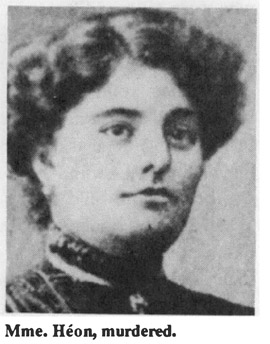

Apparently, after having murdered Cuchet, Laborde-Line, and Guillin—juggling his time tables closely in the cases of the last two—Landru felt it was dangerous to keep his villa at Vernouillet. He moved to the village of Gambais, renting the Villa Ermitage from M. Tric in December 1915. He said his name was Dupont and that he was an engineer from Rouen. This was to be his murder headquarters for several years to come. A few weeks later, Landru enticed 55-year-old Mme. Heon to the Gambais villa. She was a widow whose son had been killed in the war and whose daughter had just died. Landru consoled her and promised marriage. She went to Gambais with him; after Dec. 8, 1915, Mme. Heon was seen no more. Landru’s neighbors noticed that the chimney at his villa belched black smoke at odd hours. He had purchased a new stove when he occupied the villa. This stove would be one of the chief exhibits at Landru’s murder trial years later.

A short time later, Landru again inserted one of his lovelorn ads in the Paris newspapers. It read:

Widower with two children, aged forty-three, with comfortable income, affectionate, serious and moving in good society, desires to meet widow with a view to matrimony.

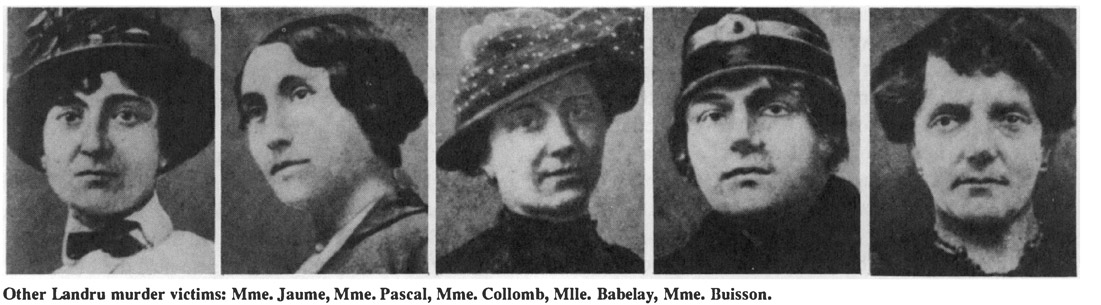

This ad was answered by yet another widow, 45-year-old Mme. Collomb, a typist who was living with a man named Bernard who had refused to marry her. Mme. Collomb had saved more than 10,000 francs, a tidy sum Landru covetously eyed. But before this lovesick woman succumbed to Landru’s persuasive ways, she insisted that he meet her family. He stalled but then reluctantly agreed to meet the woman’s relatives. Landru at the time was using the alias of one of his victims, Cuchet. None of Mme. Collomb’s relatives liked Landru and her sister, especially, found him odious and offensive. Mme. Collomb nevertheless went off with Landru to his Gambais villa and, after Dec. 24, 1916, was seen no more.

On Mar. 11, 1917, Landru’s youngest victim, Andree Babelay, went to see her mother. The 19-year-old girl who had lived in poverty all her life, told her mother that she had met a wonderful man in the Metro and that she intended to become his bride. Babelay accompanied Landru, who bought two tickets to Gambais and a single ticket returning to Paris. Andree Babelay was last seen alive on Apr. 12, 1917. The next victim was Mme. Buisson, who had been corresponding with Landru for more than two years. She was a 47-year-old widow with a nest egg of 10,000 francs. After announcing to her relatives her plans to wed Landru, she disappeared on Aug. 10, 1917. Her killer appeared in her Paris apartment with a forged note from Mme. Buisson, which demanded her furniture. This was taken to Landru’s second-hand furniture store, the Neuilly garage.

His next victim was Mme. Jaume, who had separated from her husband and gone to a marital agent who introduced her to Landru. Using the name Guillet, Landru soon took Mme. Jaume off to Gambais and her doom. She was last seen leaving her house in Rue de Lyanes with Landru on Nov. 25, 1917. Landru appeared in Paris a few days later and withdrew Mme. Jaume’s savings, 1,400 francs, from the Banque Allaume through forged documents. Mme. Pascal was next, a 36-year-old Landru had been seeing on and off since 1916. She had little money, but, like the young Babelay, she met his strong and almost incessant need for sex. Landru, using the alias of Forest, kept Mme. Pascal in a Paris apartment until he tired of her. He then took her to the Gambais villa on Apr. 5, 1918, where she, like her predecessors, went up in smoke.

In 1918, Mme. Marchadier began corresponding with Landru, who was using the alias of Guillet. Mme. Marchadier owned a large house on Rue St. Jacques, but she had little money. Landru promised to buy her house from her but had little cash himself. He proposed marriage and, on Jan. 13, 1919, Mme. Marchadier left with Landru to go to the villa at Gambais. She brought along her two small dogs and both she and the dogs were seen no more after a few days. Landru later appeared in Paris, selling off Mme. Marchadier’s house and belongings.

Landru’s many victims left considerable relatives searching for vanished women. This proved to be Landru’s undoing. On Apr. 11, 1919, Mme. Lacoste, the sister of Mme. Buisson, one of Landru’s early victims, spotted Landru strolling down the Rue de Rivoli with a young, attractive woman on his arm. She followed Landru to a china shop where she pretended to examine items while overhearing Landru ordering some china and giving the name of Lucien Guillet and an address for the delivery of the china. Mme. Lacoste then went to police with this information and detectives returned to the shop and obtained Landru’s address on the Rue de Rochechouart. Here, on Apr. 12, 1919, officers found Landru living under the alias of Guillet with a 27-year-old clerk, Fernande Segret, who was planning to go off with Landru to his villa in Gambais. The intervention of the police undoubtedly saved her life.

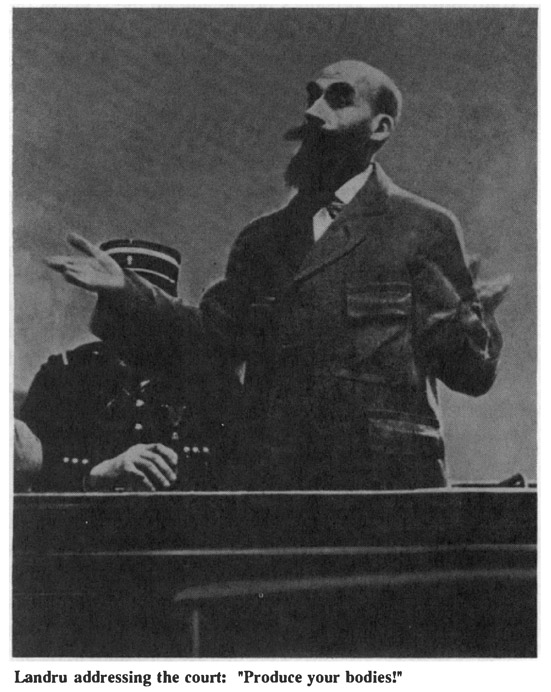

In Landru’s pocket detectives found a black loose-leaf notebook which contained cryptic remarks about many of the women he had taken to Gambais. Landru was arrested and charged with murdering Mme. Buisson. He was then taken to the villa in Gambais where the gardens were dug up and the villa torn apart. Only the bodies of three dogs were found buried in the garden. The clothes and personal effects of all of Landru’s known victims and those belonging to many more unknown women were found in the villa at Gambais, but the bodies of his victims were nowhere to be found. Landru challenged the police, as he later did the court, to “produce your bodies.” He admitted to nothing and proved utterly uncooperative.

The stove in the villa was loaded with ashes and tiny bone fragments were found inside of it. The stove was removed to a Versailles court where, between Nov. 7-30, 1921, Henri Desire Landru was tried for murder. Police had found the voluminous correspondence Landru had maintained with 283 women and almost none of them could be located. Authorities were convinced that Landru murdered them all, but busy as he was in the murder-for-profit business, it would have been humanly impossible for him to have juggled that many romances and effected that many murders from 1914 to 1919, the known period of his killings. The press, of course, made much of this arrogant, strutting mass killer, aptly dubbing him “Bluebeard,” a name that had once been attached with terror to France’s all-time mass killer, Gilles de Rais.

The press obtained a copy of Landru’s notes, wherein he had systematically classified all those writing to him in response to his lovelorn advertisements. He had labelled each group of marital applicants:

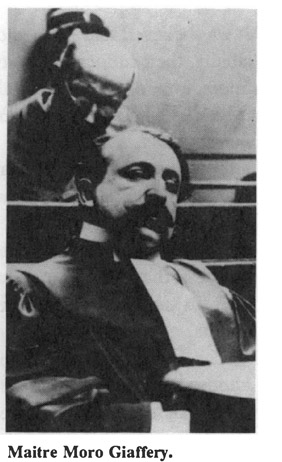

It was believed that Landru drugged his victims into insensibility, then suffocated or strangled them. He then spent hours, even days, chopping the bodies into tiny pieces and exhaustively burning the remains, meticulously taking care not to leave any traceable remains. Landru’s defense attorney was the brilliant Maitre Moro Giaffery who found that his client agitated the court and defied the prosecution to convict him without the presence of bodies. Landru claimed that the whereabouts of his female friends was his business, that these women had been his clients, and he had been in the furniture business with them at one time or another.

The court was filled up with bulky exhibits during Landru’s lengthy and volatile trial. In addition to the stove, which sat ominously before the bench, a great deal of furniture was piled up in the courtroom, all items which Landru had filched from his victims. Meanwhile, Landru became a dark cause célèbre. Cartoons portrayed him in the newspapers and ribald songs about him and his lady killings were sung in Paris music halls. Reporters from around the world came to sit in court each day and write thousands of pages about the bald, bearded killer in the dock.

Moro Giaffery worked hard to develop a line of defense. The best he could offer was that his client was no murderer but a white slaver who had abducted the women in question and had shipped them to brothels in South America. The prosecution destroyed this theory with ridicule. Roared Prosecutor Robert Godefroy in derision: “What? Women who were all over fifty years of age? Women whose false hair, false teeth, false bosoms, as well as identity papers, you, Landru, have kept and we captured?”

“Produce your corpses!” shouted Landru, his usual refrain. He occasionally found time for jest. At one point, the presiding judge asked Landru if he were not an habitual liar. Replied Landru: “I am not a lawyer, monsieur.” He was brazen and bold to the point of shocking the court. When his notebooks with their incriminating but cryptic data were presented to him, Landru merely shrugged and then sneered that he was not obligated to interpret his codes for the court. He mockingly added: “Perhaps the police would have preferred to find on page one an entry in these words: ‘I, the undersigned, confess that I have murdered the women whose names are set out herein.’” It was then pointed out to Landru that his neighbors at Gambais had often complained about the putrid smell emanating from the smoke belching from the chimney of his villa. Landru ran a bony hand over his bald head, jerked his head upward and laughed menacingly, saying: “Is every smoking chimney and every bad smell proof that a body is being burned?”

The evidence that the prosecution did produce was enough to convince a jury of Landru’s guilt. He was convicted and sentenced to death. At that time, he smiled and bowed to the courtroom, which was packed with female spectators anxious to examine this strange little man. All were fascinated with the secret powers and persuasion he held over his female victims. Knowing this, Landru said, before leaving court for the last time: “I wonder if there is any lady present who would care to take my seat?”

France’s modern Bluebeard was arrogant and distant to the end. On Feb. 25, 1922, a priest entered his cell to give him religious comfort on this, the last day of his life. He asked the mass killer if he wished to make a last confession. Landru waved him away and then pointed to the guards who had come to escort him to the waiting guillotine. “I am very sorry,” he said, “but I must not keep these gentlemen waiting.” He then walked between his guards into the courtyard of the Versailles prison and up the stairs of the scaffold. His hands were tied behind his back, his legs were tied together, and his shirt was ripped off. Landru was then placed upon a plank and his head was placed upon the block. In seconds the blade of the guillotine descended with terrifying suddenness, decapitating him.

Lang, Howard, 1935- , U.S. Howie Lang offered a cigarette to his 7-year-old playmate, Lonnie Fellick, and then casually informed him: “That will be the last one you ever smoke.” In the presence of a third boy, 9-year-old Gerald Michalek, Lang threw Fellick to the ground and attacked him with a switchblade and a heavy stone in Thatcher Woods, northwest of Chicago. Satisfied that Lonnie was dead, Lang and his friend covered the body with leaves.

Howard Lang was only twelve years old when he murdered Fellick on Oct. 18, 1947. The young suspect attended classes at the Von Humboldt Grammar School on the city’s far northwest side. Lang had a 17-year-old girlfriend named Anna Mae Evans, who hid his blood-stained clothes. His defiant air surprised and shocked police officials. Lang giggled as he reconstructed the murder for Police Sergeant Robert Fisher. The three boys took a streetcar to the forest preserve and walked to Thatcher Woods. “Lonnie asked me for a cigarette and I gave him one, and then he said he was going to tell my mother that I took $10 of her money.” That’s when Lang noticed the thirty-five-pound concrete boulder imbedded in the ground.

Howard knocked Lonnie to the ground, stabbed him, and then crushed him with the stone. Gerald Michalek told police what happened next. “Howie told me to hold his legs or else I’d get it the same way. I thought Lonnie was breathing when we left but I was sure he’d die. I covered him with the leaves.”

The two boys went to the home of Ana Evans, who refused to believe the story. The next day, she and two older boys went to the forest to see for themselves. Anna took Lonnie’s blood-soaked clothes with her and hid them in the woods.

When the state’s attorney’s office received the evidence of the crime from Chicago police, a decision was made to prosecute the boy to the fullest extent of the law, despite the long-standing policy of the Illinois courts that prohibited criminal prosecution of offenders under the age of fourteen. Serious questions were raised about a child’s understanding of right and wrong. The police and the state’s attorney believed that Lang knew what he was doing and they pressed for a murder indictment.

The boy was eventually convicted, but the decision was reversed by the Illinois Supreme Court on Apr. 27, 1949. The ruling was handed down by Judge John Sbarbaro who explained that Lang was too young to be able to distinguish between right and wrong. As a result he was acquitted of all charges.

La Satira, See: Spinelli, Evelita Juanita.

Latham, James Douglas, 1942-65, and York, George Ronald, 1943-65, U.S. James Latham, nineteen, and George York, eighteen, escaped from the guard house at Fort Hood, Texas, on May 24, 1961, to “wage war against the world.” The two buck privates hated serving in the army under black officers. Latham and York were arrested by Utah state policemen on June 10 for the murders of seven people in five states.

Latham and York began their cross-country killing spree on May 26 in Baton Rouge when they assaulted Edward Guidroz, forty-three, of Mix, La. They left Guidroz in the road and made their escape in his pickup truck. Thinking the man was dead, the two soldiers continued east until they reached Jacksonville, Fla., where they strangled two vacationing Georgia women, 43-year-old Althea Ottavio and 25-year-old Patricia Anne Hewitt, who were playing a “lucky hunch” at the dog tracks on May 29. The two women were found near their abandoned car on June 7. They had been choked with their underclothing.

Racial hatred was their reason for killing 71-year-old John A. Whittaker of Shelbyville, Tenn., on June 7. After robbing the black man of his money, Latham and York shot him in cold blood. Whittaker’s body was found near the abandoned pickup stolen from the recovering Guidroz.

They drove into Illinois on June 8 where they robbed and killed 35-year-old Albert Reed of Litchfield, and Martin Drenovac, fifty-nine, of Granite City. They explained that they would not have killed Drenovac had he not tried to wrestle their gun away.

On June 8, Otto Ziegler, a 62-year-old man from Sharon Springs, Kan., became their sixth victim. Ziegler, who worked as a road master for the Union Pacific Railroad, was found shot to death off U.S. 40, three miles east of Wallace, Kan. He had pulled off the road to help York and Latham, who pretended to have car trouble. They ordered Ziegler to drive his pickup to a remote spot off the side of the road. After Ziegler turned over $51, York and Latham shot him as he leaned over to retrieve his discarded wallet. The killers left the body in the ditch and stole Ziegler’s red Dodge. “That was their fatal mistake,” Kansas police later recalled, “Three boys who were driving farm equipment on the road saw them get out of the truck and back into the car.” The pair drove through Cheyenne, Wyo., into Craig, Colo., where they stopped at a local carnival. There they met 18-year-old Rachel Marian Moyer, who worked as a maid at the Cosgriff Hotel.

York convinced Moyer to accompany them to California for the weekend, explaining they had to pick up a “prisoner.” The two men, going by the names Ronnie and Jim, left the carnival with Moyer shortly before midnight on June 9. Before reaching the highway, Moyer stopped at the Cosgriff Hotel to inform the night clerk of her plans. The next day, Moyer’s body was found on a deserted road south of Craig. She had been shot three times in the face and chest.

Sheriff Faye Gillette of Tooele County, Utah, issued an all-points bulletin for the arrest of the men driving the red Dodge, suspecting them of the Kansas murder. A roadblock was set up on U.S. 40 near Grantsville. Their car was stopped and in the glove compartment police found two revolvers. One had eight notches carved into the handle. Latham said they would have shot it out with police, but did not want to endanger their passenger, 21-year-old soldier Vincent Olson, who was hitchhiking to San Francisco. Colorado and Florida both lost their battles to extradite the teenage killers back to their states to stand trial. The two men were returned to Sharon Springs by agents of the Kansas Bureau of Investigation on June 14.

George York and James Latham had only one request to make of their captors: that they be executed together in the electric chair. The courts were unable to accommodate the request. The glib, defiant pair were convicted of murdering Otto Ziegler. On June 23, 1965, Latham and York were taken to the gallows in Lansing, Kan., where they were hanged.

Latimer, Irving, 186-1946, U.S. Irving Latimer, the son of wealthy parents, was born in 1866 in Jackson, Mich. At the age of twenty-three, Latimer, a handsome, well-educated young man, operated his own pharmacy. Since his father’s death two years earlier, Latimer had lived with his widowed mother. Latimer soon incurred substantial debt through mismanagement of his business or, more likely, through bad habits. In addition to owing the tax collector and about sixty creditors, Latimer had also borrowed $3,000 from his mother which was due on Jan. 31, 1889.

On Jan. 24, Latimer made one of his frequent “buying” trips to Detroit. Although Latimer usually stayed in the more elegant Cadillac Hotel, on this occasion, he registered at the second-rate Griswold. Late in the morning of Jan. 25, authorities told Latimer that his mother had been murdered the night before. Her badly beaten body, which had two bullet wounds to the head, was found in her bedroom. Neighbors noted that she had not let her dog out in the morning, and called police. The police initially assumed the crime to be a bungled burglary. But investigation revealed that none of the murdered woman’s valuables had been disturbed and no one had heard her dog barking in the night, though they did when they tried to rouse Mrs. Latimer the next morning.

While trying to locate Latimer, police chief John Boyle spoke to the boy Latimer had left minding the pharmacy. The boy claimed that Latimer had refused his request for the day off, saying that he had to be a pallbearer at a funeral in Detroit. Boyle finally located Latimer at the Griswold. When questioned about the funeral, Latimer explained that he had lied to his employee to avoid having to delay his trip. Finding Latimer’s responses unsatisfactory, Boyle began searching for witnesses who might disprove his alibi. A railroad conductor on the Michigan Central Railroad said he had picked up a passenger in Jackson at 6:20 on the morning of Jan. 25. The man demanded a sleeper, which he immediately closed himself into, and he left the train in West Detroit, ten or fifteen minutes before reaching downtown. From photographs supplied by the police, the conductor identified the man as Latimer. In Detroit, the Griswold’s night porter told police he had seen a man slipping out a side door of the hotel at about 10 p.m. on Jan. 24. The maid assigned to Latimer’s room reported that she had found it empty and the bed unused the next morning. She also saw a man she identified as Latimer entering the room stealthily fifteen minutes after she had checked it.

The case against Latimer grew When a barber near the hotel identified Latimer as the nervous young man who had come in for a shave between nine and ten on the morning of Jan. 25. When the barber pointed out to Latimer that he had blood on his coat, Latimer replied that he had a nosebleed. Finally, with the testimony of two conductors who had seen Latimer on the train going toward Jackson on the night of Jan. 24, Chief Boyle concluded that he had enough evidence to arrest Latimer for his mother’s murder.

Latimer hired two expensive lawyers with some of his inheritance from his mother’s estate. During the trial, he changed his story and admitted having come back to Jackson on the night of the murder. He explained that he had followed a prostitute named Trixy, whom he thought had boarded the Jackson-bound train. Despite his alibi and his attorneys’ efforts, Latimer was found Guilty. As there was no capital punishment in Michigan, Judge Erastus Peck sentenced Latimer to life imprisonment.

Four years later, Latimer, having proven an ideal prisoner, was serving a snack to prison guards on Mar. 26, 1893. He had prepared these snacks frequently, but this time he laced the food with prussic acid and opium. Although he claimed later that he had only intended to knock the guards out, one of them died. Latimer escaped but was captured and returned to prison three days later. Latimer once again became the ideal prisoner and gradually regained his privileges within the prison. In 1935, the governor of Michigan granted Latimer a release. Latimer was sixty-nine years old and had spent forty-six years in jail. He became a vagrant for five years until he was put into a state home for the elderly. Latimer died at the Eloise State Hospital in 1946 without ever confessing to his mother’s murder.

Laubscher, Miemie, prom. 1957, and van Jaarsveld, Jacobus Frederick, 1935- , S. Afri. When she became involved with a younger man, a married woman and her new lover eventually conspired to murder her drunkard husband, later blaming each other for the crime at their trials.

Miemie Magdalena Josina de Jager married Marthinus Johannes Laubscher, nicknamed Spokies, a car mechanic, in Zastron, South Africa, in 1950. Her husband-to-be promised to stop drinking before they wed, but resumed drinking shortly after their marriage. Children had no effect on him, and the couple grew increasingly unhappy as he physically assaulted his wife, piled up debts, and engaged with her in constant fights.

In 1956, Laubscher brought home a friend, 21-year-old Jacobus Frederick van Jaarsveld, another car mechanic, who frequently visited and often stayed over at the couple’s house on weekends. After about a year, Miemie Laubscher and van Jaarseveld began an affair, soon moving to nearby Senekal where they lived together. Laubscher went to the boarding house where his friend and wife lived and asked her to return to him. She refused and they decided to divorce, the husband insisting on having custody of their children. Various complicated negotiations followed, with van Jaarsfeld actually moving back in with the reconciled couple at the husband’s invitation. As the trio continued to drink and play musical beds, the situation led to a quarrel at a party during which Miemie Laubscher apparently tried to strangle her husband. On July 10 the wife actually went to her mother-in-law and told her she intended to kill her husband so she could leave him and take the children. The mother-in-law, shocked, understandably advised her to take the offspring and leave the husband alone.

The not-surprising conclusion of this triangle occurred when the drunken Laubscher disappeared on Aug. 1. His body, strangled with a belt from his wife’s raincoat, and his head bruised from a blunt instrument, was discovered by police on Aug. 9. Weighted with a heavy steel pulley, the corpse had been dumped into the Rusfontein Dam several miles from Bloemfontein.

Both van Jarsveld and Laubscher were charged with first-degree murder. Tried before Acting Judge-President of the Free State, Justice A.J. Smith on Oct. 14, 1957, at a Bloemfontein jury trial, van Jaarsveld was found Guilty of murder “with extenuating circumstances” and sentenced to a fifteen-year jail term, in part because of his age, 21 years. Two days later Laubscher was tried before a jury and Justice D.H. Botha. With the same verdict as her lover, Laubscher was given a twelve-year jail term.

Law, Walter W., 1905- , U.S. When 28-year-old New Haven Journal-Courier reporter Rose Brancato disappeared on July 5, 1943, authorities conducted a nationwide search believing her to be the victim of amnesia. The following January, however, they arrested 39-year-old Walter W. Law, the married father of three children, when he returned from his war production job in Sparrow Point, Md., for a weekend visit with his family. After forty-eight hours of questioning, Law broke down and admitted that he lured Brancato into the basement of the Wool-worth Building and then strangled her during an ensuing struggle. Law, who had met Brancato in the Woolworth Building where she did volunteer work, then placed her body into the firebox of a boiler without knowing whether she was alive or dead.

Law signed a written confession of the crime and reenacted it for police. He pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was sentenced to life in prison.

Le Boeuf, Ada Bonner, and Dreher, Dr. Thomas E., d.1929, and Beadle, James, d.1929, U.S. In 1927, James Le Boeuf was a power plant superintendent in Morgan City, La. When Dr. Thomas Dreher began to pay Le Boeuf’s wife unwanted attentions, Le Boeuf reportedly threatened to kill the doctor. However, Le Boeufs wife and the doctor plotted to murder Le Boeuf. On July 1, 1927, Le Boeuf was shot to death. His body, though weighted at the neck and ankles with two railway irons, floated to the surface of Lake Palourde, where some boys spotted it. Police discovered that Le Boeuf and his wife had been seen together at the lake. Ada Le Boeuf and Dr. Dreher were arrested along with James Beadle, a handyman who worked for the doctor and who actually shot Le Boeuf. The three turned on each other, but they were all found Guilty. Beadle received a life sentence and Ada Le Boeuf and Dr. Dreher were sentenced to death. They were hanged at the St. Mary Parish prison on Feb. 1, 1929.

Ledbetter, Huddie (AKA: Lead Belly), 1889-1949, U.S. A Louisiana native, Huddie Ledbetter traveled the South, taking jobs as a laborer and a cotton picker. About 1918, he murdered a man in Texas during a fight over a woman, was convicted, and sent to prison. About 1925, after serving seven years of his term, Ledbetter sang his way free. Governor Pat Morris Neff pardoned Ledbetter after the prisoner sang his request. In 1930, Ledbetter was arrested again in Louisiana for stabbing six people in a dispute over some whiskey. He was convicted and sent to the Louisiana State Penitentiary. In 1933, U.S. folk song authority John A. Lomax was searching for folk ballads and he discovered Ledbetter. Lomax helped win another pardon for Ledbetter and took the singer to New York. There he thrilled audiences with black spirituals, ballads, and work songs, singing in concert halls, night clubs, and on the radio. But once again, in 1939, he landed in prison. He stabbed Henry Burgess at a party in a New York rooming house and was convicted and sentenced to one year. Upon his release, Ledbetter resumed his singing career and, in 1949, died of a bone disease.

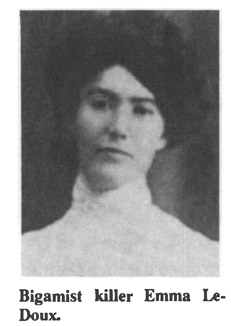

LeDoux, Emma (AKA: Emma Head; Emma McVicar), 1871-1941, U.S. Emma Head of Amador County, Calif., first married Charlie Barrett, who died in Mexico. Then she married Mr. Williams, who died under mysterious circumstances, leaving Emma a large sum from an insurance policy. In September 1902, she married Albert N. McVicar, but they separated and she worked as a prostitute.

On Aug. 12, 1905, she became the bigamous wife of Eugene LeDoux and the two lived with her mother in California. On Mar. 11, 1906, Emma met her estranged husband, McVicar, in Stockton, Calif., where the couple ordered a load of furniture to be sent to Jamestown, Calif. Shortly afterward, Emma called the store and tried to delay the shipment, but the furniture had already been sent. A few days later, she purchased morphine from a San Francisco doctor, and on Mar. 14 bought some cyanide from a pharmacy, saying she wanted to develop photographs. On Mar. 15, McVicar and his wife returned to Jamestown, where he worked as a timber man. But he quit his job on Mar. 21, saying he was going to work on a farm belonging to his wife’s mother. On Mar. 23, the couple traveled to Stockton, Calif., and Emma selected more furniture, sending it to LeDoux’s home. Sometime that night or the next day, she administered knockout drops and morphine to McVicar. On Mar. 24, she bought a trunk and ordered it delivered to her hotel. She also bought some rope and, at about 2 p.m., she had the trunk, which contained the body of her dying husband, delivered to the train station. The trunk was almost placed on a train bound for San Francisco, but since it bore no identification the trunk was sent back to the baggage room, where the baggage man and several others present noticed the peculiar odor eminating from within and called police.

Emma was arrested in Antioch, Calif., and her trial began Apr. 17. Convicted and sentenced to death, her hanging was delayed when the Supreme Court of California ordered a new trial in May 1909. Emma pleaded guilty, was sentenced to a life term in prison, and sent to San Quentin. She was paroled on July 20, 1920, but sent back to prison for parole violations on July 9, 1921. She was paroled a second time on Mar. 30, 1925, and married Mr. Crackbon, a rancher who died within two years. Her parole was yet again revoked, and in 1933 she was transferred to Tehachapi Women’s Prison, where she died in July of 1941.

Le, Barney, 1928- , U.S. On Apr. 29, 1942, Nickoli “Dick” Payne reprimanded his teenaged nephew, Barney Lee, because the boy had not finished his chores. The youngster was working on a ranch in the mountains of Monterey County, Calif. In retaliation, the 14-year-old Barney fatally shot his 36-year-old uncle. Barney was tried, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison in San Quentin where he was held in the prison hospital because officials believed that his integration with the prison population would deter his rehabilitation and, further, they had no legal right to transfer the boy to another institution.

Lee, John, 1945- , U.S. On Apr. 14, 1977, John Lee, an employee of a south suburban Chicago chemical plant, argued with another employee, 60-year-old Charles Kochenberg, after Kochenberg told Lee to finish some work. Following the dispute, 32-year-old Lee was suspended from the Stauffer Chemical Company. On Apr. 18, a disciplinary hearing was held at the plant, attended by the two employees, and management representatives John Kurzdorfer, William Good, and Thomas J. DeMarinis, and union representative Osborne Tinsley. After the meeting, Good told Lee that he would be notified of the outcome later. Lee got out of his seat and said, “You’ll tell me now.” He became more agitated, pulled out a .38-caliber revolver and shot Good in the head. Kochenberg and Tinsley escaped from the room before Lee fatally shot Kurzdorfer and wounded DeMarinis. Lee then fled in his car and, at about noon, turned himself in to Chicago police at the Englewood District Station. He was transferred to Chicago Heights and charged with murder and two counts of attempted murder. Lee pleaded guilty to the charges, was convicted, and sentenced to twenty to sixty years’ imprisonment.

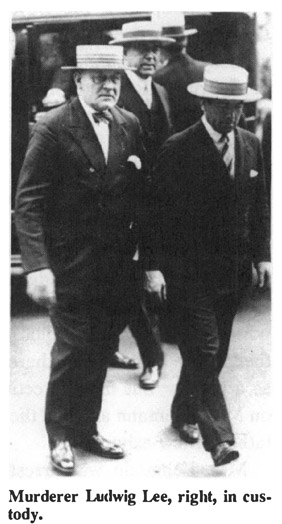

Lee, Ludwig Halvorsen, 1889-1928, U.S. While walking his beat in Battery Park, on the southern tip of Manhattan, N.Y., on the morning of July 10, 1927, a policeman found a neatly wrapped bundle on a subway air vent containing a severed human leg. The wrapping paper came from a grocery store and was covered with penciled notations. The next day a 16-year-old boy discovered a second package, wrapped much the same way, on the front lawn of a Brooklyn Catholic church. It contained the decomposing remains of a woman’s torso.

Bundles were soon found all over Brooklyn—body parts without heads—making it nearly impossible to determine who the victims were. Police did know the two bodies were female, and that the wrapping paper had come from one of two grocery store chains: Bohack’s or the A & P. But to visit every single A & P and Bohack’s store in New York’s five boroughs seemed an insurmountable task; one the homicide squad did not relish. Before their search for the grocery store clerk who might have penciled the figures on the brown paper had begun, however, Alfred Bennett of Lincoln Place, Brooklyn, came forward to report the disappearance of his wife, Selma. Last seen on July 9, 1927, by the Bennett’s 19-year-old son, John, Selma Bennett disappeared after crossing her backyard to visit 76-year-old Sarah Elizabeth Brownell, who owned a rooming house on Prospect Place.

Detective Arthur Carey of the New York Police Department visited the rooming house that night. Met at the door by 38-year-old Ludwig Lee, a Norwegian immigrant who had lived there for two years, Carey immediately cusdiscerned the sickeningly sweet smell of rotting flesh. “I think you’re coming with us,” Carey said. After Lee had been taken to precinct headquarters, a man named Christian Jensen was intercepted as he entered Brownell’s rooming house. A long-time employee at a Brooklyn A & P, he had given wrapping paper to Lee.

A team of medical examiners found more body parts in the basement of the rooming house, including the head of Mrs. Bennett. By way of explanation, Lee said that Brownell had made repeated overtures to him, that he had finally consented to marry her, but then reneged, deciding instead to kill her and collect her $4,000 in savings. He was in the process of chopping Brownell’s body up, Lee continued, when Mrs. Bennett walked in. He killed her, too, to prevent his arrest. “It was a lot of work doing all that running around,” Lee said sardonically. After a short trial, he was convicted, and in 1928, electrocuted.

Lee, Maria Helena Gertruida Christina (AKA: Maria Helena Gertruida Christina van Niekerk), 1899-1948, S. Afri. Maria van Niekerk, the daughter of a South African family, was first married in 1915 at the age of sixteen. After two divorces, she married her third husband, 24-year-old Jan de Klerk Lee who died in 1941, apparently from tuberculosis. Within the next few years, she met Alwyn Jacobus Nicolaas Smith, took a job with Lennon Ltd., in Cape Town, and married C.J.B. Olivier. In June 1945, she shared a room in Cape Town with her lover, Smith, but she married Olivier early the following year.

After her fourth marriage, she persuaded Smith to move to Durban, and he stayed there from May to October, 1946. On Dec. 5, Lee divorced Olivier. Meanwhile, she had been stealing jewelry from her employers, and both Lee and Smith had profited from the sale of the stolen goods. After she was fired in early 1947, Lee became angry because Smith had bought a car and registered it in his name. He also lied to Lee, telling her that her mother had died, and she became enraged when she learned her mother was still alive. She apparently began poisoning Smith with arsenic in October 1946, administering larger and larger doses. The solicitous Lee attended Smith as he grew ill. She called a doctor in March 1947 and Smith recovered in the hospital. However, back with Lee, he again became ill and eventually died on May 2. After an autopsy revealed arsenic poisoning, Lee was arrested. She was held at Pretoria Central Prison and later transferred to Cape Town for her trial, which began Apr. 6, 1948. Lee was found Guilty on May 10, and was hanged on Sept. 17, 1948.

Lefebre, Jean-Marie, 1916- , Belg. On Jan. 9, 1956, the personal barber of General Emile Deisser visited his client in his Brussels home as usual. But instead of shaving the 87-year-old general, Jean-Marie Lefebre strangled him.

The general’s sister-in-law, Louise Marcette, witnessed the murder and just had time to telephone police before Lefebre strangled her with telephone wire. The 39-year-old killer then bashed the head of the 60-year-old housekeeper, Marie Foulon. He proceeded to search through the rooms for valuables. Then he walked out the front door. The police never arrived because they took down the wrong house number.

During the police investigation, someone who knew the housekeeper mentioned Lefebre and he was questioned. Police grew more suspicious when they found his fingerprints in rooms of Deisser’s house where a barber probably would not have gone. They also discovered that Lefebre had recently paid off his debts and sold several items. After further questioning, Lefebre confessed. To strengthen the highly publicized case, police reenacted the crime with the killer present, having driven him past angry and riotous mobs to the general’s house. Lefebre, forty, was tried in Brussels in November 1956. He was convicted on Nov. 28 and sentenced to death.

Lego, Donald R., 1933- , U.S. The last of seventeen victims killed in a string of murders, 82-year-old Mary Mae Johnson was stabbed and beaten to death in Joliet Township, Ill., on Aug. 26, 1983. A newspaper delivery man discovered her body later that day when he noticed she had not picked up her paper. He found her body in a living room chair. After receiving a tip from a tow-truck driver, police arrested Donald Lego. On Mar. 16, 1984, the 51-year-old Lego was convicted, and on Mar. 19 he was sentenced to death. Police said Lego was not a main suspect for the other murders in Will County.

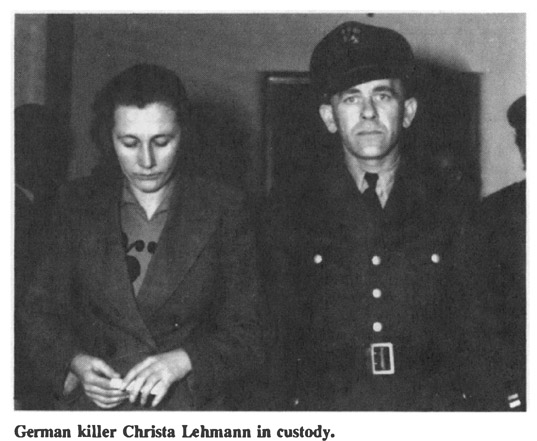

Lehmann, Christa Ambros, 1922- , Ger. Christa Ambros was alone almost from the beginning. Her mother had been confined to Germany’s Alzey mental hospital; her father, a cabinetmaker, had remarried and severed his ties to his daughter.

In 1944 she married Karl Franz Lehmann, a tile setter with a medical deferment from military service, but by 1949 Christa Lehmann was preoccupied by her affairs with American servicemen stationed in Germany, and the marriage began to fall apart. On Sept. 17, 1952, Karl Lehmann died from what physicians diagnosed as stomach convulsions brought on by an ulcer. Two years later, on Oct. 14, 1953, Mrs. Lehmann’s father-in-law, Valentin Lehmann, died much the same way as his son.

Mrs. Lehmann inherited her father-in-law’s exclusive apartment in Worms, Ger., where she often entertained her friend, Annie Hamann. A widow who lived with her 75-year-old mother, Eva Ruh, her brother Walter, and her 19-year-old daughter, Uschi, on the Grosse Fischerweide in the Old Town of Worms, Hamann associated with Mrs. Lehmann against her mother’s wishes. On Feb. 14, 1954, Mrs. Lehmann purchased five truffles from a chocolate shop and delivered four of them to friends. The fifth, earmarked for Ruh, she laced with the chemical insecticide E-605. First developed at the Bayer Works in Leverkusen by Gerhard Schroeder before the end of WWII, E-605 is virtually impossible to detect in the system. Upon receipt of the truffle, Ruh left it in the kitchen cupboard as a treat for her daughter. On Feb. 15, Hamann took one bite and dropped it to the floor. “It’s bitter,” she said, and then collapsed, suddenly blinded. When the doctor arrived, Hamann was dead; so was her dog, who had also sampled the truffle.

In his autopsy report, Professor Kurt Wagner of the Institute of Forensic Medicine in Mainz, concluded that Hamann had been poisoned, but he was not sure what the poison was until he recalled reading about E-605. Even then, he had his doubts—there was no known use of E-605 as a poison—but then detectives did a background check on Mrs. Lehmann and had the remains of her husband and father-in-law exhumed.

Mrs. Lehmann was arrested on Feb. 19, as she left Hamann’s funeral. On Feb. 23, she summoned her father and a clergyman to her jail cell and confessed to filling the cream truffle with E-605. Her intention, she said, was not to murder Ruh, but only to make her ill. “By the way,” she added, “I also poisoned my father-in-law, and I killed my husband too.”

On Sept. 20, 1954, Mrs. Lehmann was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. As a consequence of her well-publicized trial, dozens of Germans—in some instances entire families—began ingesting E-605 to commit suicide and escape the bleakness of postwar Germany.

Lehnberg, Marlene, c.1955- , and Choegoe, Marthinus, 1940- , S. Afri. South African Marlene Lehnberg aspired to become a model and to marry Christopher van der Linde, a married man nearly twice her age. She began to harass the van der Lindes with telephone calls. In September 1974, she told Mrs. van der Linde that she was having an affair with her husband. Mrs. van der Linde knew this was not true, and dismissed the girl as a nuisance. Growing more desperate by the day, Lehnberg recruited 33-year-old disabled Marthinus Choegoe.

Lehnberg promised him her car, a radio, and sex if he would kill Susanna van der Linde. On the night of Nov. 4, 1974, Choegoe entered the van der Linde’s Cape Town residence and stabbed Mrs. van der Linde to death with a pair of scissors. Witnesses in the neighborhood recognized the man with a noticeable limp and police soon picked up Choegoe. He implicated Lehnberg, who denied any connection with the crime. But Choegoe produced a note from her which read: “If you think it will be better or quicker, then use a knife, but the job must be done.”

The letter convicted the killers. Tried in Cape Town in March 1975, the pair were found Guilty of premeditated murder. Lehnberg and Choegoe were both sentenced to die, but their sentences were later commuted to life imprisonment.

Lennon, John, See: Chapman, Mark David.

Leopold, Nathan F., Jr., 1906-71, and Loeb, Richard A., 1907-36, U.S. Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb were the products of immense wealth, two brilliant students who had been allowed to expand their personalities and intelligence at will without having to work or worry about money. They had, since early childhood, been given everything, and as a result, they indulged their fantasies as their parents had satisfied their childish cravings. These two University of Chicago students, brilliant by comparison to other youths their age, had proven themselves superior in all their pursuits. Leopold, with an estimated I.Q. of 200, had graduated from the University of Chicago at age eighteen, the youngest ever to do so. He spoke nine languages fluently and was an expert botanist and ornithologist. There was, however, little warmth in his home. Leopold lived in a loveless household. Money replaced affection. His father, Nathan Leopold, Sr., was a millionaire transport tycoon who assigned a governess to his son at an early age. Babe, as Leopold had been nicknamed, came under the supervision of a sexually disturbed woman who had the boy practice all sorts of sexual perversions with her, distorting his young mind.

The Leopolds noticed their son’s reluctance to associate with girls and they unreasonably placed him in an all-girl’s school to correct his attitude. The governess went with the boy, continuing to warp his sexual growth. Moreover, this strange situation caused Leopold to reject female companionship altogether. By the time Leopold graduated from college, his mother was dead and his father, as usual, compensated for the loss by showering his son with money. He gave his son $3,000 and sent him on a European tour. When Leopold returned he was given a new car and a $125-a-week allowance and then ignored. Leopold immersed himself in the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, advocate of the superman concept. But the youth was anything but the physical ideal He was stoop-shouldered and undersized. He had an overactive thyroid gland and he was physically unattractive with huge, bulging eyes and a weak chin. He was a sexual deviate at age fourteen when he met Richard Loeb, another early-aged homosexual.

Loeb was later to fulfill Leopold’s concept of the superman. He was also the son of a millionaire, and like Leopold, had been spoiled with gifts and money since childhood. At thirteen, Loeb became Leopold’s sexual master and continued to dominate him until they sought what they considered the ultimate thrill, that of murder. Loeb was always the leader. He grew up a tall, handsome, and clever youth. He was a charming and captivating conversationalist. His father was a senior executive for Sears, Roebuck, and Co., and he bestowed a $250-a-week allowance on his son, a sum that amounted to twice that earned by most men during the early 1920s. Loeb also suffered from physical defects. He had a nervous tic, stuttered at times when nervous, and suffered fainting spells which had been interpreted as petit mal epilepsy. He often talked of suicide with Leopold, and his character, beneath the glossy charm he showed to others, was decidedly morose and fatalistic.

A graduate of the University of Michigan at age seventeen, Loeb believed himself to be an excellent detective, and his most passionate daydream was to commit the perfect crime. He often talked of this with Leopold, who encouraged his superman theories with such a crime. The two not only satisfied each other in their sexual liaison, but they fed upon each other’s egos and together believed themselves to be perfect human beings. The youths had two driving obsessions. With Leopold it was abnormal sex, and with Loeb, crime. Both were later termed by their own defense attorneys as “moral imbeciles.” It was Loeb who led the pair into active crime. At first Leopold resisted the idea, but Loeb perversely withheld his sexual participation until Leopold agreed to commit crimes with him. They signed a mutual pact in which both agreed that they would support the other’s needs.

This agreement had been signed when Leopold was fourteen and Loeb was thirteen and the youths embarked on setting fires, touching off false fire alarms, committing petty thefts, and vandalizing the homes of their wealthy neighbors. They spent months creating an elaborate system in which they could expertly cheat while playing bridge, the game of the rich and socially esteemed. They constantly argued with each other, but neither formed friendships with other children. The arguments grew violent and Loeb beat up Leopold on several occasions. Both boys threatened to murder each other someday. Loeb laughed at this idea, saying he would kill himself before Leopold could murder him.

When Leopold told Loeb that he would be going on an extended tour of Europe, Loeb proposed that they commit a spectacular crime before Leopold’s ship sailed. Leopold was reluctant but Loeb appealed to his lover by cleverly positing the idea as worthy of Friedrich Nietzsche, Leopold’s intellectual idol. Loeb wrote Leopold a note which read: “The superman is not liable for anything he may do, except for the one crime that it is possible for him to commit—to make a mistake.” This prompted Leopold to reconsider Loeb’s proposition. The most dangerous crime, the most serious crime, was the only type of crime that Loeb would consider and that, of course, was murder.

They would kidnap and kill someone, and then send a ransom note and collect money for a victim who was already dead, mocking the awful crime they meticulously planned to commit. They were utterly unconcerned with the identity of the victim, as long as that person came from wealthy parents who could afford to pay the ransom. Loeb took Leopold to his room and showed him a typewriter that he had stolen in November 1923 from the University of Michigan when he graduated. Since this typewriter could not be traced to them, Loeb reasoned, the ransom note could be typed on it. The next step was to obtain a car that could be used for the kidnapping. Both boys knew, of course, that their own cars might be identified, so they established fake identities which would enable them to rent a car. This element of their plan was elaborate, but it provided the youths with some dramatic play-acting.

One spring morning in 1924, Leopold, using the alias of Morton D. Ballard, checked into Chicago’s Morrison Hotel. He registered as a salesman from Peoria. He then went to the nearby Rent-A-Car agency and selected a sedan. The salesman asked for a reference and Leopold gave him the name of Louis Mason, along with a phone number. The salesman called Mason (who was really Loeb) who gave “Ballard” an excellent recommendation. Leopold then took the car around for about two hours and returned it to the agency, telling the salesman that he would pick it up later when he needed it. Loeb and Leopold had already used their aliases to open up bank accounts. They intended to deposit the ransom money in these accounts.

Several weeks before the crime, Leopold and Loeb had boarded the 3 p.m. train for Michigan City, Ind. Loeb brought along small parcels the size of those in which the ransom money would be paid and threw these parcels from the rear platform of the observation car at points selected by Leopold, open fields where Leopold had, months before, spent time studying birds. Returning to the car rental agency, Leopold obtained a car on May 20, 1924, and he and Loeb then drove to a hardware store on 43rd and Cottage Avenue. Here they purchased a chisel, a rope, and hydrochloric acid. All these were tools of murder. The rope was to be used to garrote their victim, the chisel to stab him in case he struggled too much, and the acid to obliterate their victim’s identity. The murderous pair debated the use of sulfuric acid before opting to use hydrochloric.

On the morning of May 21, 1924, Loeb wrapped adhesive tape about the handle of the chisel to allow a firmer grip. This, along with the rope and acid, were placed in the rented car, along with strips of cloth to be used to bind their victim, and a lap robe to cover the body. A pair of hip boots were also put into the car to be used in burying the body in a swamp the killers had previously selected. Both Leopold and Loeb each pocketed a loaded revolver, and Loeb carried the ransom note typed the day before. This note demanded $10,000 for the return of the victim, who they had no intention of returning. Neither boy needed the ransom money, but they had to make it appear that the kidnappers were lowly, money-craving underworld types, motivated by cash, not the “supreme thrill” they both sought. This element of the plan Loeb thought to be the most ingenious. Police, he told Leopold, always pinned their investigations on motive and worked backward; with the false clue of cash-hungry kidnappers planted, the police would never look for two respectable, well-to-do students. Never, he said.

The most bizarre aspect of these dark procedures was the fact that on the very day they planned to commit the crime, May 21, 1924, the boys had not yet picked out a victim. This cold indifference was the root of their inhumanity, their utter lack of moral code. They did not care about the human life they were about to take. The identity of their victim was of total unconcern to their clinical minds. The person to be killed was merely another element of their test to prove their own superiority. The victim was a number, a thing. Leopold and Loeb sat down and wrote out a list of possible kidnap victims. First they thought to kidnap and murder Loeb’s younger brother Tommy, but they dismissed the idea, only because both felt that it would be difficult to collect the ransom from Loeb’s father and that Loeb might arouse suspicion.

Little William Deutsch was then discussed. He was the grandson of multimillionaire philanthropist Julius Rosenwald. He, too, was eliminated since Rosenwald was the president of Sears, Roebuck and Co., and thus, Loeb’s superior. The Deutsch boy was simply “too close to home” for the murderous youths. Richard Rubel, one of their few friends, was also considered as a candidate for the kidnapping-murder. Rubel often had lunch with Leopold and Loeb, but he was dismissed after the killers concluded that his father was a tightwad and would probably refuse to pay a ransom for his son. What to do? The boys finally decided to pick a random victim in the neighborhood. They got into the rented car and cruised around a few blocks near Leopold’s home, focusing upon the young boys coming and going from the Harvard Preparatory School. This was an exclusive school which was attended by children of very wealthy parents.

As they drove, the killers casually discussed their problem. They agreed that they should select a small child since neither of them was strong enough to subdue a child with any strength. They stopped next to the Harvard School yard, spotted little John Levinson, and decided then and there that he would be their victim. But since neither knew the address of the Levinson family, they drove to a nearby drugstore and looked it up in the phone directory. They wanted to make sure that they would have the correct address in order to send the ransom note. By the time the pair drove back to the schoolyard, the Levinson boy was leaving. Leopold, who had brought along binoculars for the purpose of selecting a victim at some distance, spotted Levinson across the field.

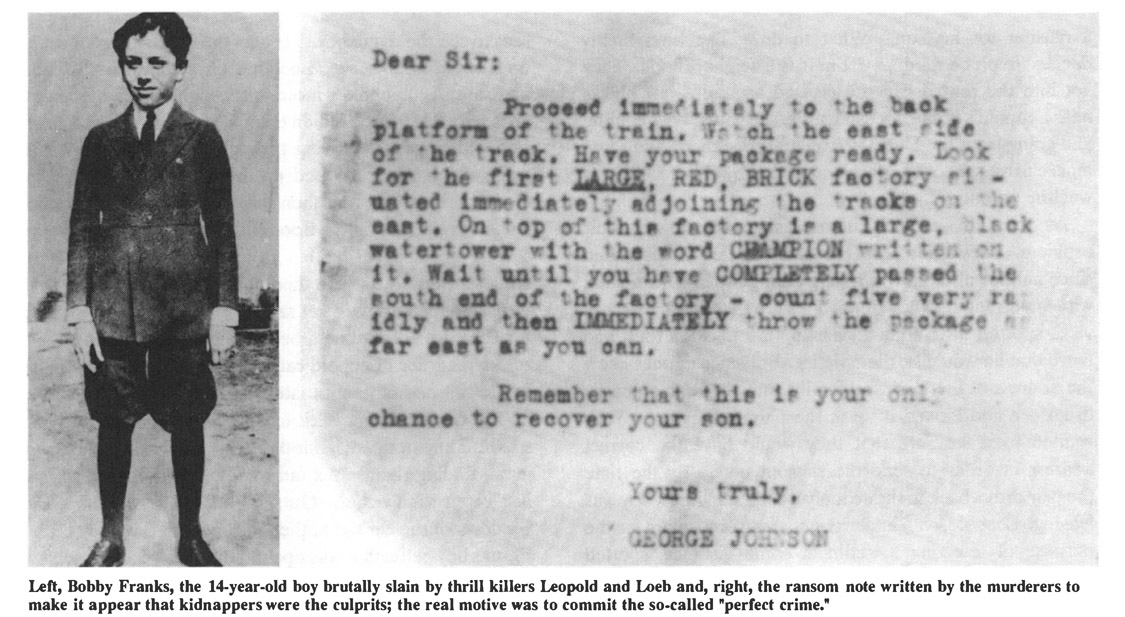

Loeb drove at considerable speed around the block in order to catch up with their prey, but the Levinson child went up an alley and vanished. Frustrated, the pair drove about aimlessly, searching for a victim. As they drove down Ellis Avenue they spotted some boys playing. One of them was Bobby Franks, a distant relative of Loeb’s. “He’s perfect,” Loeb stated, telling Leopold that the Franks child came from great wealth, that the boy’s father, Jacob Franks, was a multimillionaire box manufacturer, and could certainly afford to pay the ransom for his child, one he doted upon. After parking the car at a curb, Loeb called 14-year-old Bobby Franks to the car. Loeb asked Bobby if he wanted to go for a ride.

“No thanks,” Bobby said. He looked at Leopold who gave him a long, hard stare. “I don’t know this man,” Franks said, pointing to Leopold. There was some apprehension in his voice. “Besides, I have to go home,” he said. Loeb persisted, telling Bobby that they would drive him home. He recalled playing tennis with the Franks boy and knew the child had an avid interest in the sport. Loeb then told Bobby that he had a new tennis racket he wanted to show him. The Franks boy got in the back seat of the car. Leopold remained in the front seat behind the wheel, driving and Loeb got into the back seat with Bobby Franks. Leopold drove northward as Loeb fondled the rope he intended to use to strangle Franks. He quickly discarded this idea as being too clumsy. He grabbed the chisel and with four lightning moves, stabbed the startled child four times. The helpless child fell to the floor, gushing blood from savage wounds to the head.

Leopold turned briefly while driving to look in the back seat to see the dying boy. He saw the contemptuous sneer on Richard Loeb’s face. Loeb had enjoyed killing the child and said so. Leopold winced at the sight of the blood and groaned: “Oh, God, I didn’t know it would be like this!” Leopold continued driving through heavy traffic. Meanwhile, Loeb ruthlessly tied up the child, stuffed strips of cloth in his mouth, and then threw the lap robe over him. Bobby Franks lay on the floor of the back seat of the sedan slowly bleeding to death. Leopold kept driving about aimlessly until dusk. He then parked the car and the boys went to a restaurant to get sandwiches. They were waiting for the cover of darkness before hiding the body at a site selected earlier. Leopold called his father and told him he would not be home until late that night.

The boys then got back into the car and began driving south. They stopped at another restaurant and ate a heavy meal, finding themselves famished, even though they had just eaten sandwiches. Outside, parked at the curb, the windows of the car open, the lap robe and the body of the Franks boy beneath it was open to the view of all passersby. This was another element of the contempt the killers displayed for the ability of anyone to detect their crime. It was Loeb’s belief that no one in the world cared about anyone else. He joked with the somber Leopold about the fact that anyone passing the car outside could lean through the windows and pick up the robe and discover the body. “But nobody will,” he said in a low voice. Both were wholly insensitive to the murder they had committed. They ate their way through a five-course meal, concerned only with completing the routines they had established for themselves.

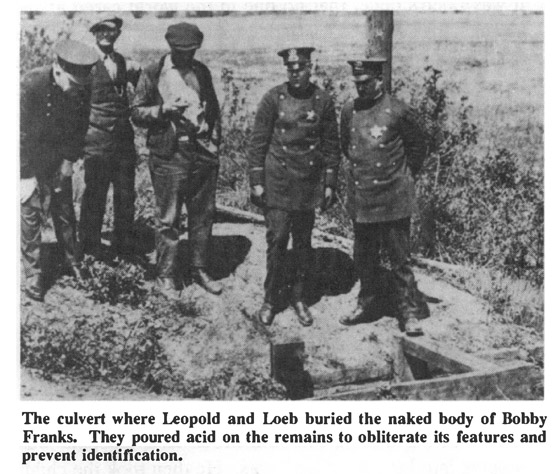

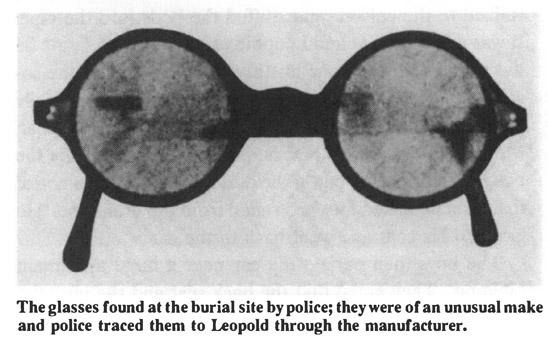

At nightfall, the killers got back into the car and drove to an area called Panhandle Tracks at 118th Street. Here a swamp drained into an open culvert and this was the spot they had selected as the burial site for their victim. Loeb got into the back seat of the car and checked the Franks boy. “He’s dead,” he announced proudly. He then stripped the boy of his clothes and poured the acid over the child’s face to mar his features and prevent identification. While Loeb was performing this monstrous task, Leopold was slipping into his pair of hip boots. He then took the child, walked to the culvert, and stuffed the body into the pipe. It was difficult work and Leopold removed his coat. As he did so, he made the one mistake that would spoil the so-called “perfect crime” he and Richard Loeb had so carefully planned. His glasses fell from the pocket of his coat. Moreover, he believed that he had thoroughly hidden the body of their victim, but in the darkness he failed to notice that a small, naked foot protruded from the drainpipe. He grabbed his coat and went back to the car.

The boys then parked the car near a large apartment building. They noted that the back seat and the lap robe were stained with Bobby’s blood. They abandoned the car and then burned the robe in a vacant lot. They went to Leopold’s house and there burned all of Bobby’s clothes, except the metal he had been wearing, his belt buckle and class pin. They typed the Franks’s address on the envelope of the ransom note and then left, driving to Indiana where they mailed the note and buried the class pin, belt buckle, and shoes of Bobby Franks. They then drove back to Chicago and Leopold called Jacob Franks, who had been worried ever since his child failed to come home that afternoon. Leopold told Franks: “Your boy has been kidnapped. He is safe and unharmed. Tell the police and he will be killed at once. You will receive a ransom note with instructions tomorrow.” Without allowing Franks to respond, Leopold hung up. The boys then made themselves drinks and played cards until past midnight in Leopold’s room, working out the final details of their “perfect crime.”

A ransom note signed “George Johnson” was delivered to Franks the next day. It demanded that Franks pay $10,000 for the return of his child, the payment to be made in twenty- and fifty-dollar bills. The bills were to be placed in a cigar box and this box was to be wrapped in white paper and then sealed with wax. Franks would receive more instructions at 1 p.m. that day, the note stated. Franks had by then notified the police through his lawyer of his son’s kidnapping. The police were told that the Franks wanted no publicity in fear that the kidnappers would murder their child, as the anonymous caller had threatened.

Meanwhile Leopold and Loeb had second thoughts about the bloodstains in the rented car. They retrieved it, drove to the Leopold house, and parked it in the family garage. Sven Englund, the Leopold family chauffeur, noticed the boys scrubbing down the back seat of this car. When he asked them about it, they told him that they had been drinking wine in the back seat of the car, borrowed from a friend, and had spilled wine on the seat. They were merely trying to remove the stain before returning the car to their friend. Englund, who had been berated and humiliated by both Leopold and Loeb over the years, would later prove his lack of affection for Leopold by staunchly maintaining that Leopold’s own car never left the family garage on the night of the Franks murder, rebuffing Leopold’s claim that he and Loeb had been using Leopold’s car that night, cruising for girls.

The typewriter on which the boys wrote the ransom note bothered Loeb. Even though it was an item stolen the previous year, he feared its discovery. Leopold drove through Jackson Park slowly while Loeb tore the keys from the typewriter and threw them into a lagoon. He threw the dismantled typewriter into another lagoon. By then it was time to contact Jacob Franks once more. Loeb boarded a train en route to Michigan City. He went to the observation car and, at the writing desk of this car, left a note addressed to Jacob Franks in the telegram slot of the desk, behind many forms. He wrote on the envelope: “Should anyone else find this note, please leave it alone. The letter is very important.” Loeb got off the train at 63rd Street to be met by the waiting Leopold. Apparently, the boys intended to inform Franks that the note was on the train and have the victim’s father personally retrieve it. However, Andy Russo, a train worker, rummaged through the forms in the telegram slot looking for a piece of paper to write on and found the letter addressed to Franks. Russo personally delivered the letter to Franks the next morning.

By this time, however, Jacob Franks knew that his little boy was dead. A member of a train crew working alongside the culvert where the body had been hidden spotted the boy’s foot sticking from the drainpipe and the corpse was quickly removed and identified by one of the Franks family. The newspapers were given the full story and huge headlines announced the brutal murder. A massive, widely publicized manhunt for the ruthless killers ensued. Scores of suspects were picked up, hustled into police headquarters, and grilled. Leopold and Loeb quickly realized that no ransom would ever be paid and that their perfect crime had serious flaws. Leopold grew silent and morose. He kept to his room, staying out of the limelight. Richard Loeb, however, revelled in the manhunt and played amateur detective. He approached police officials searching through his neighborhood for clues and offered his sleuthing services.

Loeb babbled his crime theories into the ears of detectives and followed them about during their investigations. To one he remarked: “If I were going to pick out a boy to kidnap or murder, that’s just the kind of cocky little son-of-a-bitch I would pick.” The detective took a long, long look at Richard Loeb and then encouraged him to talk further, inviting the arrogant self-appointed sleuth to accompany officers on their quest for the killer. Such conduct on the part of killers was not uncommon. In this instance, Loeb’s voluntary aid to the police was spawned by his desire to present himself as a suspect and still outwit them. It was all a game, a challenge to Loeb, who felt himself superior to the “dumb coppers” who bumbled about looking for a killer who was right beneath their noses, secretly jeering at them.

Then the “bumbling” police began to make discoveries that unnerved Loeb. Loeb’s stolen typewriter was found in the shallow waters of the Jackson Park lagoon and the keys to it were found in another lagoon. Then the bloody, tape-wrapped chisel was found. The most startling discovery was that of Leopold’s glasses. The police traced the horn-rimmed glasses to the manufacturer, Albert Coe and Co. Officials at the firm reported that the glasses were unusual, the frames being specially made for only three people. One pair belonged to a lawyer who had been visiting Europe for some time. The second pair was owned by a woman and she was wearing them when police arrived to interview her. The third pair had been sold to Nathan Leopold, Jr., dear friend of Richard Loeb, the boy who had been dogging the footsteps of investigating detectives, the self-appointed Sherlock Holmes of Chicago.

Richard Crowe, the shrewd, tough state’s attorney for Cook County, had Leopold brought into his office for questioning. He showed him the glasses and asked him if they were his. Leopold said no, his were at home. Crowe sent Leopold back home with two detectives but thorough searching of the Leopold home failed to produce the glasses. Then Leopold was told that the glasses had been found near a culvert at 118th Street, and Leopold, thinking fast, told Crowe that he often went to that area for his bird-watching studies. Crowe was hesitant to charge Leopold, initially believing that he was a victim of circumstance. He came from incredible wealth and his social position was lofty. There was no reason Crowe had to believe that Leopold had anything to do with the killing of Bobby Franks. Yet he had Leopold interrogated by two detectives who kept questioning him about his glasses and his whereabouts on the night of the murder.

Leopold first stated that he could not recollect what he was doing on the night of May 21, 1924, but he later said that he and his friend Richard Loeb had been driving around looking for girls and picked up two attractive girls named Edna and Mae. He could not remember their last names. The four of them, Leopold insisted, had gone to a Chinese restaurant on the South Side and had dinner on the murder night. Leopold then said that he and Loeb had been drinking gin out of a flask and that he did not want to talk about his outing with Loeb and the girls because Loeb’s father strongly disapproved of drinking and he did not want his friend Loeb to get into trouble.