Taborsky, Joseph, 1923-60, U.S. On Oct. 7, 1955, Joseph Taborsky was released from the Connecticut State Prison’s Death Row, where he had been sent in 1951 for murdering Louis Wolfson while robbing his liquor store with his brother, Albert Taborsky. Albert received a life sentence for turning state’s evidence. Joseph declared his innocence and called his brother crazy. Granted another trial after Albert’s transfer to a state hospital for displaying bizarre behavior, the state was left without a case and Taborsky was released.

Within a year, a wave of murders swept through Connecticut which police called the “Chinese Executions” because all the victims had been kneeling when shot from behind. The slayings began on Dec. 15, 1956, when a 67-year-old Hartford, Conn., tailor was found robbed and shot in the back of the neck. Thirty minutes later, gas station operator Ed Kurpiewski was robbed and forced into the restroom where his murderer shot him through the back of the head. Daniel Janowski, who drove up to the gas station when Kurpiewski was shot, was next. He was found in the storeroom, also shot through the back of the head. Samuel Cohn, a liquor store owner, was similarly killed eleven days later and ten days after that, in North Haven, Bernard Speyer and his wife were killed as they walked into a shoe store. The shoe store owner, who had been knocked unconscious, told police that two men had robbed the store and fatally shot the couple.

Investigations led to the arrest of Arthur Culombe and Joseph Taborsky. The shoe store owner positively identified Taborsky as the killer of the husband and wife. Taborsky confessed to those slayings, as well as to the murder of Louis Wolfson, the murder for which he was initially imprisoned in 1955. Convicted of murder, he was executed in 1960.

Tal, Schlomo, prom. 1977, and Balabin, Pinhas, 1949- , U.S. Million-dollar deals are sealed with a handshake and the Yiddish blessing “mazel un brucha” on New York City’s Forty-seventh Street between Fifth Avenue and the Avenue of the Americas. This midtown block is the center of the world’s diamond industry. Its more than 200 diamond brokers account for more than $1 billion in annual sales. Negotiation is intense, with a profit margin of only 1 or 2 percent. But the area is considered so safe that many brokers conduct their business without insurance. Robbery is extremely rare and murder virtually unheard of.

In late September 1977, the body of 25-year-old diamond cutter Pinchos Jaroslawicz, who had been missing since Sept. 20, was found bound and stuffed into a small box in the Forty-seventh Street office of another diamond cutter, Schlomo Tal. Jaroslawicz had died of head injuries and asphyxiation after a plastic bag was put over his head. The $1 million in gems he had been carrying in his wallet were missing. Earlier in the week, Tal’s wife reported him missing, but he was found sleeping in his wife’s car in Queens. Tal said two masked men entered the office and robbed and killed Jaroslawicz, and that he hid the body and did not report the murder for fear of reprisal. Tal said the two men then returned, abducted him, and drove him around Nassau County for three days, finally abandoning him after drugging him. Upon waking, he was found by the police and arrested as a material witness.

The Jaroslawicz case bore a similarity to the unsolved murders of four other diamond merchants. Leo Dershowitz and Howard Block were murdered in Puerto Rico in 1974. In 1977, Abraham Shafizadeh was also murdered in Puerto Rico, and Haskell Kronenberg was murdered in Florida. More than $1.5 million in gems were taken from the four victims. The police questioned Tal’s shaky alibi, and when they learned that he had a criminal record in Israel, they arrested him and another diamond cutter, 29-year-old Pinhas Balabin, on Mar. 30, 1978, for the murder of Pinchos Jaroslawicz. Both men were convicted of murder and sentenced to twenty-five years to life in prison.

Talbot, Lug, prom. 1930, U.S. In 1930, a bordello was set up at a sawmill camp in Hemp Hollow, near Brownsville, Ky. On Oct. 4, three men from Brownsville and three men from Rutherford, Ky., visited the brothel. The two groups fought over who would receive the women’s services first, and an ensuing brawl ended in a double killing. Oren Baylanch shot and killed Ben Talbot and was then shot to death by Ben’s brother, Lug Talbot. Lug was eventually arrested and turned over to Brake County officials. Lug Talbot pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter and was sentenced to fifteen years at the Kentucky state penitentiary. After his release, he moved to Owenton County, and in a fit of depression, he committed suicide by hanging himself.

Tansey, John, prom. 1907, U.S. In May 1907, a labor strike shut down the entire San Francisco street-car system. By Sept. 2, Labor Day, no settlement had been reached, but non-union employees kept the system running. Early the following morning, police officers P.J. Mitchell and Edward McCartney heard a ruckus at a nearby saloon. Four men were leaving as the officers approached. Two fled, but the police confronted the other two, shoved them, and warned them that they might be locked up. One of the men drew a gun and shot Officer McCartney in the neck, killing him instantly. During the ensuing manhunt, a railroad inspector stated that the man described was John Tansey, a striking carman. Tansey was arrested when the surviving officer identified him. Tansey’s partner, a man named Bell, was apprehended, and also stated that Tansey was the murderer. Tansey countered that Bell had pulled the trigger. But it was Tansey who was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to ten years in prison. He was paroled on May 10, 1909, because he had consumption.

Tarnower, Dr. Herman, See: Harris, Jean Struven.

Tarnowska, Marie Nicolaievna, See: Naumoff, Nicolas.

Taylor, Jack S., prom. 1970, U.S. On Feb. 16, 1970, the badly decomposed body of a woman was found in a swampy area near Palm Beach, Fla. A finger had been severed from the body and there was a gaping wound under its left eye. Fingerprints were taken, and the FBI identified the corpse as Judy Ann Vukich of Clarksville, Tenn. Her parents said she had moved to Florida and was living with a man named Jack Taylor. A warrant was issued and he was arrested two weeks later in Oklahoma City. He had killed Vukich for hiding liquor from him. Taylor was tried and convicted for manslaughter and sentenced to twenty years in the Florida State Penitentiary.

Taylor, Perry Alexander, 1967- , U.S. On Oct. 24, 1988, 38-year-old Geraldine Birch was choked and beaten to death on a Tampa, Fla., baseball field by 22-year-old Perry Alexander Taylor. Taylor admitted his guilt, but claimed that he had been provoked. His trial began on May 10, 1989, in the Tampa courtroom of Judge M. William Graybill. Taylor testified that he had paid the woman to have sex with him, and that she injured him during the act, prompting him to choke her and kick her repeatedly. The prosecution countered that Taylor was a habitual criminal. When he was sixteen, he had been convicted of raping a 12-year-old. The prosecution also said that his latest victim had died a slow, agonizing death. The jury agreed, and on May 12, 1989, convicted Taylor of first-degree murder and sexual battery and sentenced him to die in the electric chair.

Telles, Felix, prom. 1927, Arg. Augustin Martelletti was a partner in the firm of Cores, Martelletti, Hermanosa Cia, one of Argentina’s oldest and wealthiest firms. During the night of Jan. 17, 1927, he and his wife were murdered in their apartment above the corporate offices. The two had been beaten unconscious with a blunt instrument and then stabbed. The next morning, employees discovered the gruesome scene, and began a manhunt. The break in the case came on Feb. 12, when the owner of a cleaning establishment notified police that he had received a pair of bloodstained trousers. The owner of the trousers was identified as Felix Telles. Telles was apprehended, and when confronted with the murder weapons, he broke down and confessed. He was a former employee who knew where valuables were hidden. Attempting to burgle the office, he was surprised by the couple. They recognized him, so he killed them. In one of Argentina’s speediest trials, the judges unanimously found Telles Guilty and sentenced him to twenty years of hard labor on an island penal colony.

Terpening, Oliver, Jr. (AKA Jacobowsky), 1930- , U.S. Wondering what it would be like to watch someone die, 16-year-old farm boy Oliver Terpening, Jr., shot his 14-year-old friend, Stanley Smith, while the two boys were searching for crows outside Imlay City, Mich., on May 26, 1947.

Terpening shot Stanley with his father’s .22-caliber rifle as he rested beneath a tree. Then, when Stanley’s three sisters arrived on the scene, he shot them, too. “I thought the best thing to do was kill them all,” he said. The bodies of Barbara Smith, sixteen, Gladys Smith, twelve, and Janet Smith, two, were found several hours later by their sister, Ella Mae Smith, roughly 100 yards from where their brother had been killed. Wildflowers were found in their hands. Terpening went home and ate his dinner, but it “went down pretty hard,” as he later recalled. Realizing that the authorities were probably onto him, Terpening stole the family car and drove to Port Huron, Mich., where he abandoned it.

Without a dime in his pocket, Terpening hitchhiked through Detroit and camped out for the night in a filling station on U.S. Highway 24 near the Ohio state line. Concerned for his son’s safety, Oliver Terpening, Sr., notified the Michigan State Police, who issued a physical description of the boy on all the local radio stations.

Terpening was spotted by a farmer from Erie, Mich., as he stood on the side of the road, with his thumb out. The farmer’s son, Norman Dombrosky, Jr., recognized the hitchhiker from the radio accounts. When asked where he wanted to go, Terpening said: “Any place.” “I told him my name was Jacobowsky,” he said later, “and that I lived on Flager Street in Toledo. I’d seen that street name in Port Huron and it was the first that came to mind.” The elder Dombrosky was suspicious, so he drove to the outskirts of the city and the offices of Justice R.O. Stevens, who had Terpening arrested by local constables.

Terpening was taken back to Erie, where he was questioned about the four murders. “I’ve always kinda wondered what it would be like to kill somebody,” he said in a matter-of-fact way. “I’ll tell the truth. I did it. I just wanted to see someone die.” Terpening added that he didn’t get the kind of thrill he was looking for when he originally decided to murder his friend.

Terpening’s father told police that his son had always been a problem child. After he dropped out of the eleventh grade, he ran away to Louisiana because he could not get along with his stepmother. There were times, said the younger Terpening, when he wanted to kill her. His discouraged father sent him $25 for a train ticket when his money ran out.

Circuit Court Judge Albert Perkins signed the warrant accusing Terpening of murder. On June 10, 1947, however, Terpening was declared by three psychiatrists to be mentally unbalanced. At this writing, he remains confined in the G. Robert Cotton Correctional Facility in Jackson, Mich.

Terry, John Victor, 1940-c.1961, Brit. On Nov. 10, 1960, 20-year-old John Victor Terry, upon hearing of the execution of his friend Francis “Flossie” Forsyth, claimed he had become the reincarnation of U.S. gangster “Legs” Diamond. He then walked into a bank in Sussex, England, and shot a bank guard in the head. When apprehended, he defended his actions by saying, “When a person dies his mind leaves him and goes into another body. My mind was from Legs Diamond.” The hallucination may have been caused by Terry’s drug use. He was found Guilty of the murder, and in the end, he emulated not Legs Diamond, but Flossie Forsyth, when he was hanged from the same gallows at Wandsworth Prison.

Tessnov, Ludwig, d.1904, Ger. At the turn of the century, a German chemist named Paul Uhlenhuth, experimenting with human and animal blood, discovered that if the two samples were mixed together the blood serum of the human would not react in any way to that of the animal’s. Uhlenhuth determined that a rabbit injected with a specimen of human blood would develop a natural resistance to it. His research with bloodstains proved invaluable to criminologists and members of the legal profession attempting to use this material as evidence during important murder trials.

The first practical application of Uhlenhuth’s theories to a crime involved an itinerant German carpenter named Ludwig Tessnov, implicated in the sex-murders of four German children between 1898 and June 1901. At the same time a farmer in Gohren reported the slaughter of six or seven sheep. The entrails of the animals were scattered across a wide plain. The similarities between the mutilation of the animals and that of the children were so remarkable that the prosecutor of Greifswald asked Uhlenhuth to conduct an analysis. “If we prove the presence of sheep blood, that, along with identification by the shepherd, should make it clear that Tessnov is the killer of the sheep. And considering the way his clothing is spattered, some of it must be human blood, too.” Uhlenhuth received two bundles of Tessnov’s clothing on July 29, 1901. The scientific community anxiously awaited the results.

The tragedy of the children began in the village of Lechtingen, outside Osnabruck, on Sept. 9, 1898, when two girls, Hannelore Heidemann and Else Langemier, failed to return home from school. A search party that evening found the girls lying dead in a patch of bushes in the surrounding woods, their bodies hacked to pieces. A journeyman carpenter, identified by local authorities as Ludwig Tessnov of Baabe on the island of Rugen, explained that the red spatter marks on his work clothes were wood stains. Unable to conduct a chemical blood analysis, police released Tessnov and the murders entered the books as officially unsolved.

The shocking crime was repeated almost exactly on July 1, 1901, on the Baltic island of Rugen, when Hermann Stubbe, eight, and his brother Peter, six, failed to show up for their evening meal. The boy’s father, joined by a policeman and several villagers, searched the adjacent woods with little success. The next morning a neighbor found the mangled bodies in a thicket. The arms and legs had been hacked off and their organs scattered through the woods. Nearby investigators found a bloodstained rock that presumably had been used by the murderer. A local fruit peddler reported to police on July 2 that she observed Tessnov talking to the children shortly before their disappearance.

Tessnov was arrested on suspicion. He claimed that the spots on his hat were cattle blood and other stains resulted from varnish he used in his work. Dr. Uhlenhuth, aided by an assistant, examined nearly 100 stains. He demonstrated through sophisticated blood analysis that there were definite traces of human blood in six areas of Tessnov’s trousers, vest, and jacket. Uhlenhuth’s evidence not only helped convict Tessnov, but his work with bloodstains greatly advanced forensic science. Tessnov was executed at Greifswald Prison in 1904.

Testro, Angelina, prom. 1912, U.S. During Franklin D. Roosevelt’s tenure as governor of New York from 1929 to 1933, he pardoned Angelina Testro, who had served eighteen years of a life sentence at Auburn Prison for murdering her intended on their wedding day.

Testro, a 43-year-old widow, ran a rooming house in the Bronx. A young tenant, Arturo Costello, known throughout the neighborhood as “the Dude,” began to pay her attention, which she returned. She also lent him small sums of money to purchase a stylish wardrobe. The widow begged Costello to marry her, and they procured the marriage license. With Testro in her wedding dress and a priest waiting, a friend of Costello entered the home and said that Costello would not go through with the marriage unless he received $400. That evening, she met her lover at a nearby railway bridge. He was found shortly thereafter with a knife protruding from his chest, gasping his last few breaths.

Angelina Testro confessed to the crime, saying, “I killed him because he made a fool of me.” She was found Guilty of murder in the first degree and sentenced to death at Sing Sing. But Governor Whitman commuted the sentence to life, and she served eighteen years before being given a full pardon by Governor Roosevelt.

Tevendale, Brian, 1945- , and Garvie, Sheila W., c.1934- , Scot. Maxwell Garvie married Sheila Watson in 1955 and during the next nine years, the couple had three children. In 1967, Sheila Watson Garvie began an affair with 22-year-old Brian Tevendale, while her husband became attracted to Tevendale’s married sister, Trudy Birse. The foursome cavorted until May 14, 1968, when Maxell Garvie left on a trip from which he would not to return. Five days later, Garvie was reported missing and a search began. Mrs. Garvie admitted to her mother that she had killed her husband, and her mother went to the police. In mid-August the body of Garvie, badly bludgeoned and shot through the neck, was found in an underground tunnel.

On Aug. 17, Sheila W. Garvie, Brian Tevendale, and another friend, Alan Peters, were charged with the murder. In November, Mrs. Garvie and Tevendale were found Guilty of murder and sentenced to life. Peters was released when the court found his participation in the crime Not Proven.

Thacker, William J., d.1903, U.S. William Thacker killed John Gordon and was convicted three times: twice in a court of law, and a third and final time by a vigilante mob. In 1900 Thacker, a man in his early forties, lived in the small hamlet of Noah, in northeastern Kentucky. He owned a general store and doubled as the postmaster. A burly man who liked to drink, Thacker’s true passion in life was the Republican Party. The more he drank, the more stoic he became about his party, which had been dominated by the Democrats since the Civil War.

On July 30, 1900, Thacker, accompanied by his 16-year-old son, Robert, left his home on a hunting expedition—not for animals—but for Democrats. He bought a few bottles of liquor, announcing his intended targets to the shopkeeper. Outside the store, he encountered Gordon, a man in his early twenties, who worked at a local sawmill. Asking Gordon if he knew of any local Democrats, Gordon admitted to being one. Thacker goaded Gordon into fighting him with a knife. As Gordon advanced, Thacker drew his gun and shot Gordon in the head. He covered Gordon with brush and left him to die. Thacker was convinced to surrender and he and his son were taken to the Flemingsburg jail. Robert Thacker was later released.

In January 1901, Thacker was convicted of the murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. He appealed, and received the same sentence exactly one year later. He appealed again, but before the third trial, an angry mob gathered outside the Flemingsburg jail. After midnight on July 15, 1903, the mob stormed the jail, and dragged the screaming Thacker from his cell. Shortly after, his clothes shredded and his face gashed by rocks, he was hanged from a honey locust tree. No action was taken against the lynchers. The jury at the coroner’s inquest returned a verdict of death by persons unknown.

Thaw, Harry Kendall (AKA: John Smith), 1872-1947, U.S. Few murders among America’s social elite and super rich rivaled the sensational 1906 murder of architect Stanford White by the demented millionaire Harry K. Thaw. The slaying of White was a public affair, committed in front of hundreds of horrified spectators. Thaw performed this deed with arrogance and disdain, as if dismissing an annoying servant or an unwanted party guest. Harry Thaw was used to having his own way since childhood, and as far as he was concerned, his killing of Stanford White, ostensibly over an affair with Thaw’s beautiful wife, Evelyn, was merely a nasty chore he was compelled to perform.

The pampered Thaw was the son of a Pittsburgh magnate who had cornered the coke market in a short time and had accumulated a then staggering fortune of $40 million. Harry Thaw was the profligate heir to this fortune. Terribly spoiled by an over-indulgent mother, Thaw’s education was a shambles although he was sent to the finest schools, including Harvard, where he ignored his studies and spent most of his time conducting high-stakes poker games in his suite of rooms off campus. He was finally dismissed for gambling activities. Thaw’s father was so vexed at his son’s wastrel ways he reduced his allowance to $2,000 a year. Harry wined and carped until his mother awarded him an additional $8,000 a year. Still the headstrong Thaw complained that this was only pin money for a man of his esteem and standing.

Taking a lavish suite of rooms in Manhattan, Thaw attempted to buy his way into several prominent men’s clubs, but he was barred because of his eccentricities. Incensed, Thaw rented a horse and tried to ride it into these clubs, knocking down doormen and porters. He was arrested and escorted home. His mother paid his fine. A short time later, Thaw participated in a marathon poker game with New York sharpers and lost $40,000. His mother paid the gambling debt. To vent his wild rages and satiate his sexual perversions, Thaw took another apartment inside of one of New York’s fanciest bordellos. There he brought young, gullible women, promising them careers on Broadway or, at least, in the chorus lines of important musicals. After Thaw inveigled the women to his brothel apartment, he fiendishly attacked them, raping them and beating them with sticks and whips.

The bordello madam, Susan Merrill, later stated that she heard a woman screaming in Thaw’s apartment and when she could bear it no longer, forced her way inside. She later testified: “I rushed into his rooms. He had tied the girl to the bed, naked, and was whipping her. She was covered with welts. Thaw’s eyes protruded and he looked mad.”

Merrill ordered Thaw out of the house, and when he refused, she called the police. The millionaire playboy was escorted from the brothel despite his protests that he had paid rent a year in advance. He was barred from the brothel and Madam Merrill was happy to repay him his advance rent. A short time later, Thaw was ejected from one of the finer Fifth Avenue shops. The sales manager refused to have his models show the latest gowns to a bevy of Broadway tarts Thaw paraded into the shop. At this point Thaw had what was later described as a “sort of fit. His eyes bulged and rolled, and he screamed like a child having a tantrum.” Police escorted the playboy outside and sent him home; the whores were locked up. In retaliation, Thaw rented a car the next day and drove it through the shop’s display window, almost running over the gaping manager. Thaw was again arrested and fined.

Mrs. Thaw advised her son to leave Manhattan and take a European vacation. Thaw sailed for Paris where he scandalized a city that was weaned on scandal. He rented an entire floor of the Georges V Hotel and invited the city’s leading prostitutes to a party that lasted several days and cost him $50,000. He was finally asked to leave the hotel after he was discovered whipping naked women down the hotel corridors.

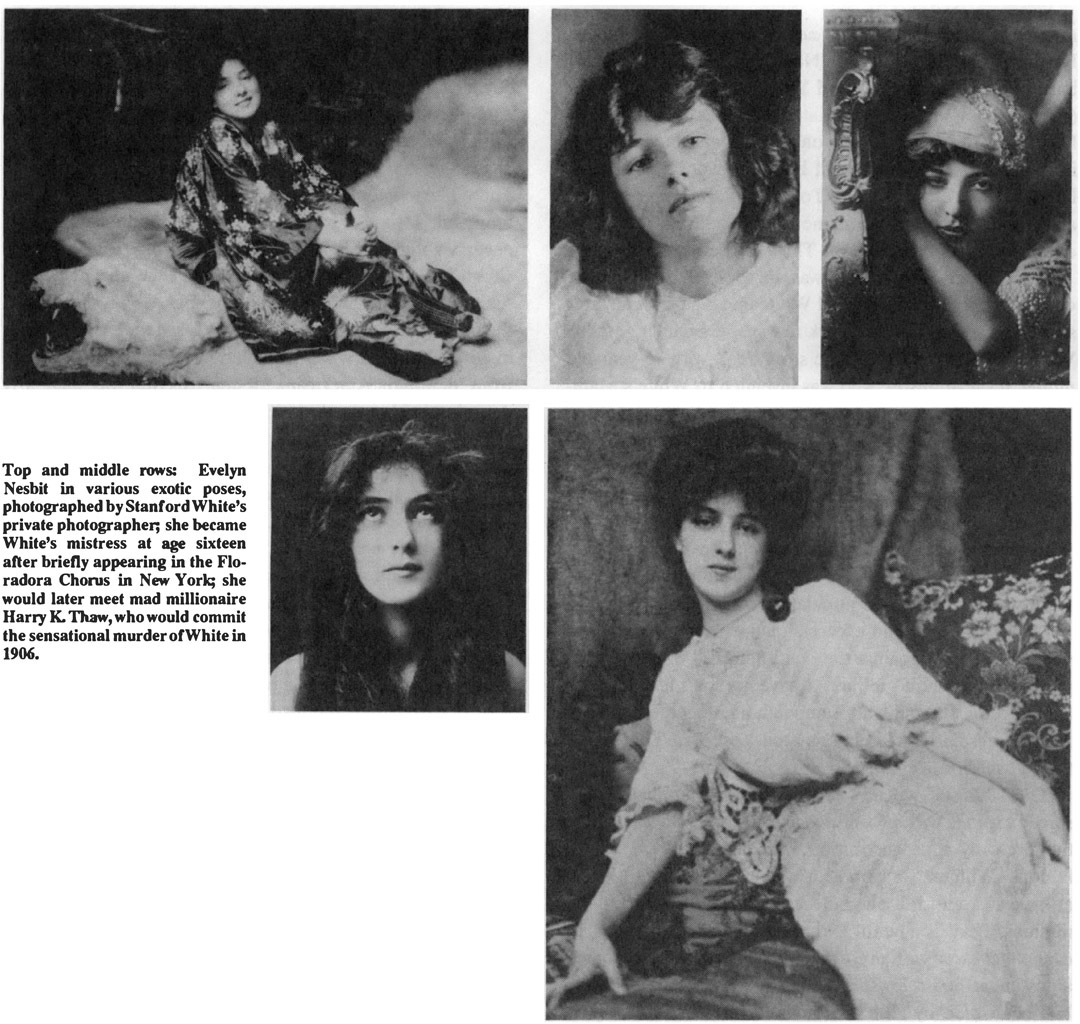

Another product of Pittsburgh at that time was a 16-year-old sultry brunette, Evelyn Nesbit. She came from poverty and had little formal education, but she had singing and dancing talent and, after being a photographer’s model for a short period of time, soon won a spot in the prestigious Floradora Sextette. While performing in the Floradora chorus, she caught the lecherous eye of Stanford White, the most distinguished architect in New York. White, who was tall and heavyset, weighing some 250 pounds, wore a sweeping handlebar mustache and was always sartorially dressed, glittering with a diamond stickpin, gold watch chain, an expensive jewel-encrusted watch fob, and rings.

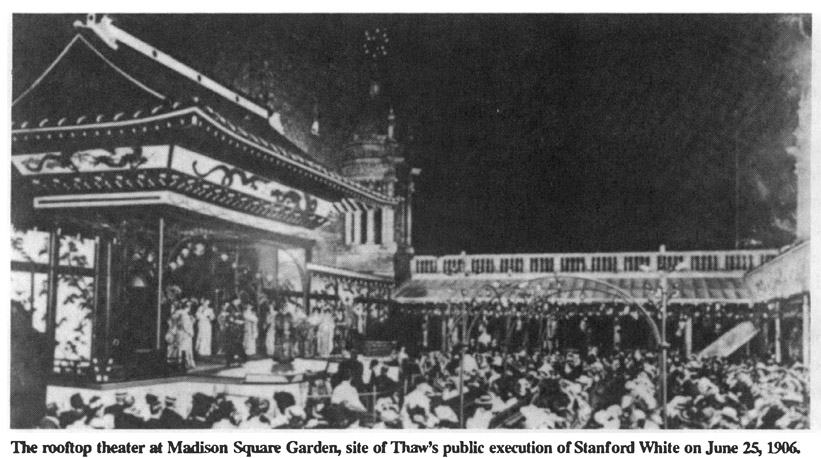

White was many times a millionaire, having made a fortune designing the resplendent Fifth Avenue mansions of New York’s wealthiest movers and shakers. He was a high society architect who catered exclusively to the super rich, although he was known widely for having designed the elegant Washington Square Arch and the Hall of Fame at New York University. He had also designed Madison Square Garden, including its restaurant, arcade, fashionable shops, the amphitheater where prizefights and horse shows were held, and the magnificent roof garden where musicals were performed for open-air audiences who dined while watching the shows.

The tower of Madison Square Garden was reserved by White for himself. There he maintained a lavish home-away-from-home (he was married but seldom saw his wife). This apartment featured a red velvet swing which hung from the ceiling of the tower. According to Evelyn Nesbit’s later statements, White was in the habit of bringing his mistresses and one-night stand show girls to the tower where he would swing them high so that he could lasciviously look beneath their billowing skirts. (The portrait of White as a lewd and lustful old man was painted by Nesbit at her husband’s trial, certainly a colored, prejudiced view which was designed to vindicate Thaw’s murderous actions, although White’s skirt-chasing habits were certainly well known long before he ever met Nesbit.)

For three years, Nesbit carried on a relationship with White. He lavished gowns and jewels on the woman, paid for her stylish apartment and chauffeured limousine, and took endless photos of her in seductive poses. When he tired of her, he sent her away to a finishing school.

Harry Thaw had also seen Evelyn Nesbit on the stage briefly and knew that she was White’s pampered mistress. While she was in boarding school, he contrived to meet her and then pursued her slavishly until she accepted his marriage proposal. Thaw, however, after the nuptials on Apr. 4, 1905, was more concerned with White than he was with his own wife, persecuting Nesbit for her relationship with the architect. He insisted that she refer to White as “The Beast” or “The Bastard.” When she refused, he told her that she must, at least employ the letter “B” whenever she mentioned White. This Nesbit did.

Thaw took his 19-year-old bride to Europe, but it turned out to be a nightmarish honeymoon. Aboard the luxury liner carrying the couple to France, Nesbit later claimed, Thaw tied her to a bed and whipped and beat her until her body was coated with red welts. She finally told her unhinged husband what he wanted to hear—or all she could imagine that was vile and rotten about Stanford White. She told Thaw that White had tricked her into going to The Madison Square Tower apartment on the promise of marriage, but once there, he stripped and raped her, and then forced her to mount the red velvet swing naked while he took obscene photos of her. This story, of course, drove Thaw into blind rages and he forced his wife to repeat this story often so that he could work himself into a frenzy about White, vowing terrible revenge against “The Beast.”

On the warm night of June 25, 1906, Harry Thaw took his berserk revenge on Stanford White. Harry and Evelyn Thaw were dining in Rector’s with two of Thaw’s friends, when White and a party of people left one of the private dining areas. Thaw stiffened as Evelyn passed him a handwritten note which read “The B. is here.” She had followed his instructions of informing Thaw any time she saw White in public. Thaw crumpled the note and pocketed it, then patted his wife’s hand and said: “Yes dear, I know he’s here. I saw him. Thank you for telling me.”

A few hours later White was sitting at the best table on the Madison Square Garden rooftop to witness a new, frothy musical, Mamzelle Champagne. White was interested in one of the chorus girls to whom the manager promised to introduce him following the performance. Harry, Evelyn, and two of their friends also arrived at the Madison Square Garden rooftop.

Evelyn saw White sitting alone watching the show and, early-on, asked Thaw to take her home, noticing the agitated state he was in. She told her husband that the show bored her and he got up and began to escort her and their friends to the elevator. Suddenly, he was gone. Minutes later he stood glaring down at Stanford White. The architect looked up at Thaw, whom he knew and disliked. “Yes, Thaw, what is it?” White reportedly asked the staring young man. Without a word, Thaw reached into his pocket and withdrew a revolver, pointing it only a few feet from White’s head. He fired one shot and then two more. White, his face a mass of blood, collapsed on the table, then fell sideways, taking the table with him. He sprawled dead on the floor with a bullet in his head and two more in his shoulder.

At first there was a horrible silence. The show stopped completely, performers frozen on the stage. The band did not play a note. The hundreds of customers present stared at the bizarre scene of Thaw standing over the fallen White and then piercing screams came from the women and everyone made a mad dash for the exits, knocking over tables and chairs in a panic to escape what they thought was a madman on the loose.

Thaw, according to some witnesses standing near him, raised the revolver over his head and emptied the remaining three live cartridges from the weapon which fell to the floor. He said something that was later interpreted to mean: “I did it because this man ruined my wife.” Some claimed that Thaw said: “This man ruined my life.”

Within seconds, Thaw, still holding the weapon above his head, made his way to the elevator where Nesbit and his friends waited in shock. “My God, Harry,” Nesbit said. “What have you done?”

The roof garden was by then in pandemonium with women screaming and men shouting for police officers. The manager leaped upon a table and shouted to the band: “Go on playing!” To the stage manager he cried: “Bring on the chorus!” At this moment, a doctor was leaning over White and saw part of White’s face blown away, his entire head was blackened by powder burns from bullets fired at close range. The physician pronounced White dead.

In the elevator lobby, Thaw, still clutching the weapon, was confronted by an off-duty fireman who said: “You’d better let me have that gun.” Thaw meekly turned it over. A policeman then arrived and Thaw submitted to arrest. He was marched to the Center Street Station where he said his name was John Smith and was a student living at 18 Lafayette Place, New York City. He was searched and his own identification papers quickly revealed his true identity—Harry Kendall Thaw, the millionaire.

“Why did you do this?” a sergeant asked Thaw.

Thaw stared blankly at the policeman for some moments, then replied: “I can’t say.” He refused to make any more statements until his lawyer arrived. Thaw was charged with murder and placed in a cell in the New York Tombs to await trial. Fifteen months passed before Thaw was brought into court, a stalling tactic designed by Thaw’s brilliant defense attorney, California criminal attorney Delphin Delmas, who had defended hundreds of clients in murder trials and claimed never to have lost a case. Delmas was called “the little Napoleon of the West Coast bar.” Hired for an estimated $100,000 by Thaw’s mother (the figure was never substantiated), Delmas told the elderly Mrs. Thaw that because her son chose to execute his victim in public, the best they could hope for would be to keep him out of the electric chair. To that end, Delmas mounted a crusade to blacken the name of the victim, a shameless and brazen technique to win Thaw any kind of sympathy.

Press agent Ben Atwell was hired by Mrs. Thaw to destroy the image of Stanford White and a short time later stories appeared in New York newspapers which detailed White’s profligate ways. One story dealt with 15-year-old model Susan Johnson, who was inveigled to White’s Madison Square Tower apartment, which the Evening Journal described as being “furnished in Oriental splendor.” The tale was told how Susan Johnson was plied with liquor, seduced, and soon afterward abandoned by the heartless White to make her way penniless through life. The vilification campaign against White went on day after day, month after month, until, it seemed Stanford White had seduced half the female population in New York City.

Mrs. Thaw made no excuses for unleashing the dogs of slander and libel against the dead Stanford White. “I am prepared to spend $1 million to save my son’s life,” she had announced. The publicity campaign and legal fees for her son’s defense, it was later estimated, cost Mrs. Thaw more than $2 million.

Thaw himself was not spared negative publicity. His sordid exploits with prostitutes and his wife were leaked to the press by the prosecution which was headed by the famous William Travers Jerome, New York’s district attorney. Said Jerome before the trial: “With all his millions, Thaw is a fiend! No matter how rich a man is, he cannot get away with murder, not in New York!” Jerome’s aides unearthed a lawsuit filed against Thaw in 1902 that had been filed by Ethel Thomas. Her story was almost identical to the one later told by Evelyn Nesbit. After meeting Thaw, Thomas had been swept off her feet by Thaw who oozed affection and respect. He had given her flowers, jewels, and clothes. “One day,” Thomas stated in her deposition, “I met him by appointment and we were walking toward his apartment at the Bedford, and he stopped at a store and bought a dog whip. I asked him what that was for and he replied laughingly: ‘That’s for you, dear.’ I thought he was joking but no sooner were we in his apartment and the door locked than his entire demeanor changed. A wild expression came into his eyes and he seized me and with his whip beat me until my clothes hung in tatters.”

The most bizarre ploys were used by the defense to create hatred for White and glean sympathy for the “befuddled” Thaw. One story related how a medium had conducted a seance on July 5, 1906, and that a “spirit from beyond appeared to insist that he, a long-departed soul named Johnson, had guided Harry Thaw’s hand” and the spirit was the true killer of Stanford White, not Thaw!

Finally, on Jan. 21, 1907, Thaw was brought to trial. Thaw himself took the stand to appear penitent and remorseful, saying: “I never wanted to shoot that man. I never wanted to kill him …Providence took charge of the situation.” Apparently Thaw had read the account of the seance and was now pinning the blame on the spirits. Delmas and his battery of lawyers insisted Thaw was not in his right mind when he killed White, that he suffered from “dementia Americana,” a neurosis that was singularly American; wherein American males believed that every man’s wife was sacred and if she were violated, he would become unbalanced, striking out in a murderous rage.

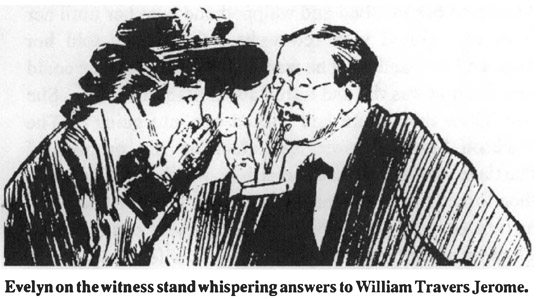

District Attorney Jerome fought back against this psychological gobbledygook, cross-examining Evelyn Nesbit with dogmatic persistence. He asked about the character of her husband and her replies were so explicit that she insisted on whispering her answers to him. Her responses were later whispered for the court reporter recording the trial transcript and then her sordid stories were shown in printed form to the jury members. By then, however, the jury believed that Stanford White was a beast in human form and deserved to die, that he had ruined the lives of dozens of young women and that Thaw, who was unhinged at the time of the shooting, was merely doing what any noble-minded American male would do, taking vengeance for wronged women all over the U.S.

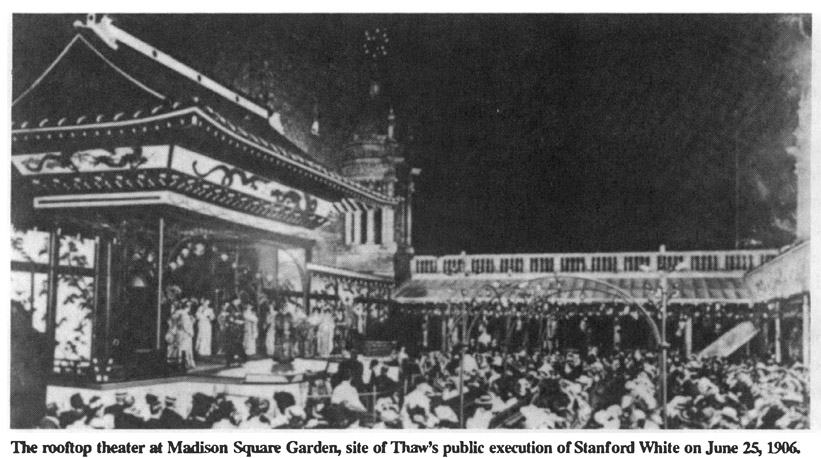

The jury, on Apr. 11, 1907, could not agree, seven holding for conviction, five others insisting on a not guilty vote. Thaw was tried again, and, on Feb. 1, 1908, he was found Not Guilty “by reason of insanity.” This was the verdict Delmas had sought. His client would not face the electric chair. Thaw was sent to the New York State Asylum for the Criminally Insane at Matteawan, N.Y. He was to remain here for life, despite efforts by his mother to free him.

When Mrs. Thaw’s millions could not move the courts, she reportedly financed her son’s escape on Aug. 17, 1913. Thaw was escorted through unlocked doors to freedom where a limousine was waiting for him. He was driven to Canada and a luxury apartment. The U.S. State Department brought heavy pressure against Canadian officials to have Thaw returned to the U.S. and he was finally turned over, but he was placed in a Concord, N.H., jail where, as had been the case in the New York Tombs while he awaited trial, Thaw dined on catered meals and was offered every convenience and comfort. His lawyers ardently battled extradition to New York until December 1914 when they secured another trial for the murderer.

In the third trial, the same evidence and testimony was examined, but the jury, on July 16, 1915, returned a verdict of Not Guilty and also stated that Thaw was no longer insane and urged his release. He was set free. In 1916, Thaw was back in the news, accused of kidnapping, beating, and sexually molesting 19-year-old Frederick B. Gump. He was arrested, jailed, and went through another trial where he was declared insane. Another hearing was held and Thaw was declared sane and the charges were dropped. It was reported that Thaw’s mother had bestowed more than $500,000 on the Gump family to convince them to drop the charges. Thaw then resumed his eccentric lifestyle, buying his way through life. He died in February 1947 of a heart attack, a wizened, shrunken creature of seventy-six.

Evelyn Nesbit had her moment of glory and infamy during the Thaw trial and for some years afterward. She was abandoned by the Thaw family, who reportedly bought her off. She later appeared as a vaudeville attraction, billed as “the girl in the red velvet swing.” In 1915, though she had long been divorced by the irresponsible Thaw, Nesbit insisted that her newly born son was Thaw’s child, that she had bribed guards at Matteawan to allow her into Thaw’s rooms for a night of bliss. Thaw angrily denied this and his parentage. His lawyers reportedly paid her off.

Therrien, Armand R. prom. 1975, U.S. In 1975, Chin Enterprises was a four-man partnership which owned the popular Hawaiian Garden Restaurant in Seabrook, N.H. The corporation sought to borrow $166,000 from a Boston bank to open another restaurant in Marietta, Ga. Three of the four partners were oriental, but the fourth, referred to as Uncle Harry, was a former New Hampshire state policeman named Armand R. Therrien. As a policeman, he specialized in cases involving embezzlement. In 1973, he resigned to become an insurance agent. He had severe financial difficulties after he divorced and began doing odd jobs at the Hawaiian Garden, eventually becoming secretary-treasurer of Chin Enterprises. In January 1975, Therrien left Boston to supervise the construction of the Marietta restaurant.

On Feb. 11, 1975, in the Boston suburb of Westwood, two patrolmen, William Sheehan and Robert P. O’Donnell, approached a car with its emergency lights flashing. The driver appeared to be slumped in his seat. A man exited a passenger-side door and approached the officers, assuring them that the driver was ill but not in need of help. But the officers, suspecting a drunk driver, looked in the driver’s window and saw blood. As they turned to confront the passenger, Therrien, he shot them with a .38-caliber snub-nosed pistol. Sheehan died of a bullet wound to his head. O’Donnell survived with two minor wounds, and was able to return fire and wound Therrien. The driver of the car, John Oi, one of Therrien’s partners, had been killed before the officers arrived.

Authorities speculated that Therrien, supporting two households since his recent divorce, was financially strapped. A bank loan secured by Chin Enterprises stipulated that corporate officers were limited to annual salaries of $15,000. Chin Enterprises had insurance policies on all partners, which would pay the corporation $200,000, or more than enough to pay back the loan and return a handsome amount to each partner, thus solving Therrien’s cash flow problem. Therrien was arraigned and brought to trial at Dedham, Mass. The jury found him Guilty of first-degree murder in the deaths of Oi and Sheehan and sentenced him to two consecutive life terms at the Massachusetts Correctional Institution at Walpole.

Therrien, Joseph W., 1925- , and St. James, George L., 1930- , U.S. Police in Bristol, Conn., received a phone call on Christmas night 1948, telling them about the body of a woman lying in the snow. The caller identified herself as Rose Lombard!, who said she had stumbled over the body on her way to the garbage bin. “Who is she?” Police Chief Edmund S. Crowley wanted to know. The distraught Lombard whose Christmas celebration was upset by the tragedy replied, “I never saw her before. I have no idea how she got here—or why.” Medical Examiner Fred T. Tirella examined the corpse and determined the woman had been strangled a few hours earlier.

The police searched the immediate vicinity. Entering a locked barn they found a late-model automobile containing a tube of lipstick, a twenty-dollar bill, and several long strands of hair trapped in the screw socket of the rear window frame. The vehicle had been rented to a neighbor who had an unshakable alibi. But the car was somehow linked to the slaying. That much seemed certain when detectives found a woman’s handbag lying in the snow near the barn. Inside the purse was a small slip of paper with the word “rich” scrawled in pencil.

No further action was taken and the investigation was stymied until a mortician from Plainville notified police that he knew of a family named Rich in his community. Digging further, the police learned the body was that of Lillian Rich, estranged wife of Harold Brackett. The Plainville police reported that Rich, in her forties, had been evicted from a local cafe with two young men half her age. The three had been drinking and carousing loudly. One of the youths was identified as 23-year-old Joseph W. Therrien, who had been previously arrested for burglary and car theft. Therrien had served six months in prison, but had recently taken up residence at the home of Rose Lombardi in Bristol. When asked about this by Chief Crowley, Lombardi said that she had not seen Therrien for several days. The police obtained a search warrant.

In the Lombardi basement they found a damp, mud-stained dress. A charred, half-burned Social Security card bearing the name of Lillian Rich Brackett was found inside the furnace. “What a Christmas!” wailed Lombardi. “Now you won’t believe a word I say!” She went on to say that Therrien, his friend George St. James, and a drunken woman had stumbled into her kitchen on Dec. 24. The young men, chased out of the house, took Brackett to the garage where they raped her in the neighbor’s car, and then strangled her to death. A hole was dug in the ground and the body buried. Then they told Lombardi what had happened. Fearing her boarders had buried the woman alive she told them to dig up Brackett and bring her to the kitchen. There they carefully scrubbed the body and changed the clothing, using one of Lombardi’s housedresses. It was a snug fit, but she decided it would pass. The corpse was next placed in the snow to make it look like an accident. “But why on earth did you protect these killers?” Crowley asked. “I had to,” Lombardi replied. “Therrien is engaged to my daughter and I didn’t want anything to happen to postpone the marriage.”

Lombardi’s hopes for her daughter’s marriage were dashed when Therrien and St. James were committed to the state prison for life. As an accessory to murder, Lombardi received three years.

Thomas, Allgen Lars, See: Haerm, Teet.

Thomas, Arthur Alan, prom. 1970, N. Zea. Jeanette and Harvey Crewe were a New Zealand couple living on a farm near the village of Pukekwa. One day in June 1970, Jeanette’s father stopped by the farm and found the couple’s 18-month-old child, apparently abandoned. Bloodstains were found, and the police, aided by the army, mounted a massive search. On Aug. 16, the body of Jeanette Crewe was found in the Waikato River, wrapped in a sheet. She had been shot in the head with a .22-caliber bullet and bound with wire. Exactly one month later, the body of Harvey Crewe, killed by a bullet of the same caliber and weighted down by a car axle, was found in the same river. Test firings of all .22-caliber weapons in the area led police to suspect Arthur Alan Thomas, a neighboring farmer. Officials later learned that Thomas had once courted Jeanette Crewe. In November 1970, he was charged with the double murder. In February 1971, in the Auckland Supreme Court, Arthur Thomas was found Guilty of the murders and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Thomas, Donald George, c.1925- , Brit. Police constable Nathaniel Edgar stopped a suspicious-looking character while patrolling a crime-ridden area of London on Feb. 13, 1948. People nearby heard three shots, saw a man running from the scene, and found that an officer had been gunned down. The mortally wounded officer had obtained his assailant’s name and address and had them written in his notebook—Donald Thomas, 247 Cambridge Road, Enfield.

Thomas was an army deserter who had been on the military’s wanted list for many months. The police tracked Thomas down and arrested him as he was trying to hide the gun that had killed Edgar. Police also found rounds of ammunition, a rubber truncheon, and a book on handgun shooting. Furthermore, he had confessed the crime to his landlady.

In April, Thomas was tried, found Guilty of murder, and sentenced to death. The sentence was commuted to life in prison because the courts enacted a temporary suspension of the death penalty.

Thomas, Edward, 1920- , U.S. On Apr. 22, 1941, 73-year-old Addie Gilman was found dead on the floor of her Brooklyn home, an apparent suicide. Gas jets had been left on and there were no signs of a violent struggle. Also, she had been depressed by the departure of her daughter, who had moved upstate. However, no suicide note was found, and upon further examination of the corpse, officials determined she had been strangled.

The murderer had left no clues, but a note indicated that the woman had recently had financial troubles with the upstairs tenant, Jerry Croft. A search of her diary entries uncovered the name of Croft’s brother-in-law, Edward Thomas. Also, a friend of Gilman’s had stopped by for a visit just before her murder. Gilman was expecting another visitor soon, and mistakenly called out “Hello, Eddie” when he arrived. The friend, however, did not see Gilman’s other visitor. This, plus the diary entries, led detectives to Edward Thomas. Thomas, a 21-year-old airport mechanic, was greeted by detectives Harry G. Lavin and William Brennan when he returned home from work. He admitted he had been in the Gilman home, but only to negotiate a settlement of his relative’s back rent. Detective Lavin continued to question Thomas, finally accusing him of choking Gilman. The suspect then blurted out information only the killer would have known. Realizing his error, Thomas confessed. On June 3, 1941, Edward Thomas pleaded guilty to first-degree manslaughter, and three weeks later was sentenced to a term of ten to twenty years in Sing Sing.

Thomas, Leonard Jack, 1903- , Brit. In London on Mar. 13, 1949, Leonard Jack Thomas stabbed his estranged wife, Florence Ethel Lavinia, thirteen times with a jackknife. She survived and on May 2, Thomas was sentenced at the Old Bailey to seven years in prison for attempted murder. Then his wife died of her injuries, and Thomas was ordered to be retried for murder. On July 13, the defense moved for dismissal, as Thomas was already serving time for the same attack, and no man could be put in peril twice for the same offense. However, the plea was rejected and Thomas stood trial for murder. He then pleaded temporary insanity stating he and his wife had had an argument over dancing lessons, but that he had blacked out, only to find himself standing with a knife over his wounded wife. The jury was unsympathetic and sentenced him to death. However, more than 12,000 people signed an appeal, begging for mercy, which was sent to the home secretary. The king, on the advice of the secretary, commuted the death sentence.

Thompson, Edith Jessie (Edie), d.1923, and Bywaters, Frederick, d.1923. Brit. Edith Thompson and Frederick Bywaters became lovers during Summer 1921. Bywaters, a sailor, was a family friend of Thompson and her husband, Percy, and in June had accompanied the couple on a vacation at the Isle of Wight. The Thompsons began to experience marital discord, and by September Thompson was secretly meeting Bywaters during his extended leaves from sea. The affair continued into the following year until late in the evening of Oct. 4, 1922, when Percy Thompson was stabbed to death by an assailant as he and his wife were returning to their London home. Police encountered an hysterical Edith Thompson, who proclaimed that she had done everything within her power to save her husband’s life. Authorities might have believed her, but a neighbor stepped forward and told of the relationship with Bywaters.

Searching Bywaters’ quarters, police discovered sixty-two letters from Edith proclaiming her love and detailing aborted attempts to poison her husband. The couple was arrested, and Bywaters was charged with the Percy Thompson murder, Edith Thompson charged with being an accessory. They were brought to trial on Dec. 6, 1922, in the Old Bailey courtroom of Justice Shearman. Sir Henry Curtis-Bennett, defending Thompson, and Cecil Whiteley, defending Bywaters, attempted to have the letters dismissed as evidence, but prosecutor Sir Thomas Inskip successfully won their inclusion. Bywaters confessed to the attack but said it was in self-defense and in no way premeditated. He further absolved Edith Thompson of any complicity. But Thompson took the stand and, under intense interrogation, admitted the details of the affair and conversations with Bywaters about eliminating her husband. The jury of eleven men and one woman deliberated for two hours before finding both defendants guilty of murder. Amidst pleas of innocence, both were sentenced to death. They appealed, were denied, and at 9 a.m. on Jan. 9, 1923, Edith Thompson swung from the prison gallows at Holloway, while Bywaters met a similar fate a short distance away at Pentonville.

Thompson, Elizabeth, prom. 1971, and Fromant, Kenneth Joseph, 1939- , Brit. On Nov. 5, 1971, the body of 35-year-old Peter Stanswood was found in a parked car on a road near Portsmouth, England. Stanswood, a local businessman, had been stabbed seven times with a Japanese paper knife. The ensuing investigation revealed that Stanswood, a married man with two children, had been involved in an extraordinary number of extramarital affairs. Two of the women bore his children, while a third woman was pregnant. A prime suspect would have been his wife, but it was revealed that Heather Stanswood had had about two dozen lovers of her own. The most recent was Kenneth Fromant, a 39-year-old gas company worker, who had a criminal record. It was further revealed that Peter Stanswood was involved with Elizabeth Thompson, the wife of his business partner.

Nine months after the murder, a Scottish woman stated that her boyfriend had been at the crime scene with Kenneth Fromant. On July 17, 1972, Fromant was interrogated and stated that he had spent the night with Elizabeth Thompson. However, his blood matched the sample taken from the victim’s car, and soil samples from Fromant’s car tires matched similar samples on the other car. The police waited almost three years, until May 19, 1975, to arraign Fromant and Heather Stanswood on the charge of murder. Stanswood was soon released, and Thompson arrested instead. Thompson stated that she had met Stanswood but they had been surprised by Fromant. A fight ensued and Fromant killed Stanswood. Thompson was formally arrested on Aug. 5, and ordered to stand trial with Fromant.

At the trial on Oct. 21, 1975, at the Winchester Crown courtroom of Justice Talbot, Fromant admitted to being at the murder scene but stated that the killer was Elizabeth Thompson. The jury sentenced them both to life imprisonment.

Thompson, George (AKA: Buck Jones), d.1962, S. Afri. Dillie and Koos Scholtz, a happily married young couple, had good jobs, a nice home, and were quite content in Greenways, a suburb of Cape Town, S. Afri. On July 3, 1961, Koos left for work at about 8 a.m. and Dillie twenty minutes later. When Dillie Scholtz failed to arrive at work, the police were called. Soon it became apparent that Dillie Scholtz had disappeared within a few minutes of leaving the house that morning. Her car was still parked in the garage.

When the police arrived, Koos described his wife’s usual routine, and they explored the grounds. While they were in the alley, they were greeted by George “Buck Jones” Thompson, a local handyman who was known to the police as an occasional informant. Buck, apparently somewhat drunk, said he had not seen the woman.

On July 9, while excavating a compost heap a short distance from the garage, the police discovered Dillie Scholtz’s body, buried with her purse, keys, a coat, and some work she had been taking to her office. The body, which was burned, was in a sack and had a necktie tied around the throat. One of the constables assigned to the case recognized the necktie as belonging to George Thompson. Investigation determined that on the morning of the murder Thompson was seen by one of his friends standing by a fire near the garage. He had told his friend to wait for him and that he would buy him a drink. He showed up a short while later with a shopping bag and plenty of money.

Thompson was charged with murder. During his trial, he tried to implicate another person, but the chain of evidence was too strong and he was found Guilty of premeditated murder. He was hanged on Mar. 29, 1962.

Thompson, Tilmer Eugene, prom. 1963, and Mastrian, Norman, 1924- , and Anderson, Dick, prom. 1963, U.S. St. Paul, Minn., attorney Tilmer Thompson and his wife Carol, the parents of four children, had met while attending Macalester College together in the late 1940s. On Mar. 6, 1963, Carol Thompson was attacked in her home, stabbed twenty-five times in the head and face, and clubbed with a blunt object. She died in the hospital after collapsing on a neighbor’s doorstep. Cartridges from a luger pistol that had evidently misfired were found on the floor of the victim’s home.

A few days after his wife’s murder, Tilmer Thompson was seen in a local nightclub with an attractive woman. Investigators also discovered a dozen insurance policies on his wife’s life, worth more than $1 million, naming him as the sole beneficiary. And his wife was sole heir to her parents’ million-dollar fortune. Three extension phones had recently been removed from the Thompson house, and the family’s pet dog, which had served as protection for the family, had been given away.

On Apr. 9, Minneapolis salesman Wayne F. Brandt reported to police that a luger pistol had been stolen from him on Feb. 14. On Apr. 17, two small-time hoods arrested for an attempted hold-up of a St. Paul bar admitted stealing the luger from Brandt’s apartment. They gave the gun to Norman Mastrian, who in turn was seen handing it to Dick Anderson. Mastrian, a 39-year-old ex-boxer, had been suspected of a 1961 murder, but was released. He was also a college classmate of the Thompsons. On Apr. 19, he was arrested for his involvement in the Thompson murder and police began to search for Anderson, whom they arrested shortly in a Phoenix motel. Anderson tried to plea bargain, hoping to reduce the first-degree murder charge.

On June 20, he confessed to murder, saying that Mastrian had hired him to kill the woman in a manner that made her death seem accidental.

Tilmer Eugene Thompson was arrested and charged with first-degree murder on June 25, 1963, by the Ramsey County Grand Jury. On Dec. 6, 1963, before Judge Donald Odden, Thompson was found Guilty of instigating the murder plot and sentenced to life imprisonment “at hard labor.” Dick Anderson and Norman Mastrian were also found Guilty and sentenced to life.

Thompson, William Paul (AKA: Bud), 1938-89, U.S. William Paul “Bud” Thompson spent 28 of his 51 years in prisons or reform schools on various charges, including breaking and entering, counterfeiting, forgery, and murder. In April 1984, Thompson killed a 28-year-old transient, Randy Waldron, in Reno and was sentenced to die by lethal injection. After that sentence, he was also convicted of the murders of two brothers near an Auburn, Calif., campsite. Thompson confessed that he had killed three others and stated that if freed he would likely kill again. On June 18, 1989, the 300-pound Thompson was given a last supper of four double bacon cheeseburgers, two large orders of fries, and a large cola. At 2:01 the following morning, at the Nevada State Penitentiary in Carson City, he was given a lethal injection, and he died eight minutes later.

Thorne, John Norman Holmes, d.1925, Brit. Elsie Cameron, a plain, rather thin, neurotic young secretary fell in love with young John Thorne. Although Thorne, a Sunday school teacher and boys’ club supporter, was a most unlikely choice, being a less-than-successful chicken farmer who lived in a shack on his squalid little farm in Sussex, Elsie still wanted him. In November 1924, after a lengthy correspondence in which she falsely claimed she was pregnant, Elsie kept insisting on coming to see him and that they get married. Thorne, in response, informed her that he was involved with another woman and was not interested.

In spite of her erstwhile lover’s protestations, Elsie packed her bag and left London to confront John face-to-face on Dec. 5. Six days later Elsie’s father sent John Thorne a telegram asking of Elsie’s whereabouts. John replied that although he had expected her she had not arrived in Sussex.

John informed the police that he had not seen Elsie, but witnesses came forward to say that they had definitely seen her going to the farm. The police then returned to the farm to dig up the chicken yard and discovered her dismembered body.

Thorne claimed that while he was out of the house, Elsie had hanged herself. In a panic, he had tried to dispose of the body. However, an autopsy revealed that she had been beaten to death. He was charged with murder and tried at Lewes Assizes in March 1925. He was found Guilty of murder and was executed at Wandsworth on Apr. 22, 1925.

Thorne, Thomas Harold, b.1896, Brit. In early 1921, Harry Blackmore, a 61-year-old man from Hampstead, England, was found dead from twenty stab wounds to the head. His assailant, 25-year-old Thomas Thorne was apprehended, but found insane, and sentenced to a mental institution in Broadmoor. In 1937, Thorn was released with tragic results. After working briefly as a tobacconist in Chester, he attacked a woman Alice Hannah Johnson, who barely survived. Before Justice Singleton at the Chester Assizes, Thorne was sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

Thornhill, Hillary, 1915- , and McCain, Willie B., 1930- , and Robertson, Eugene, 1928- , U.S. In 1960, Hillary “Hill” Thornhill was the bootlegging kingpin of rural Columbia, Miss. A local sheriff, J.V. Polk, had recently declared war after years of casual enforcement, and Thornhill brought in two men, Willie McCain and Eugene Robertson, to eliminate the problem. The two men made two unsuccessful attempts on Polk’s life, before Robertson withdrew. But on Apr. 22, 1960, McCain succeeded, killing Sheriff Polk with a 12-gauge shotgun at a distance of seventy-five feet. All three conspirators were arrested and all confessed to the plot. Thornhill and McCain were sentenced to life imprisonment, while Robertson was sentenced to ten years.

Tiernan, Helen, 1911- , U.S. Helen Tiernan, a divorced mother of two, loved George Christodulas, a poor Greek immigrant, but she could not marry him—until her children were out of the way. She lived in a two-room tenement flat on West Forty-seventh Street in New York City. Described as quiet and reserved, Tiernan supported her children by working as a stitcher at an Eighth Avenue embroidery firm. The money her boyfriend earned as a steward at the Foltis-Fischer restaurant on Seventh Avenue was not enough to move the four of them into larger quarters. Deciding that the love of this man was more important to her than the lives of her children, Tiernan took her 7-year-old daughter Helen and 3-year-old son James down to the Pennsylvania Railroad Station on May 15, 1937, where she boarded a train bound for Brookhaven.

She told them they were going on a picnic in the woods. But in her suitcase she carried the murder weapons: a carving knife, hatchet, scissors, and a bottle of gasoline. In a dense thicket near busy Yaphank Road, Tiernan cut Helen’s throat and then poured gasoline on her. The girl fell to the ground as her mother lit a match. She struck James with the hatchet, but he ran off before the fire could be started. When the 3-year-old was found later that afternoon by Warren Brady and May Savage of Long Island, all he could say was “Mommy! Mommy!” A hundred feet away, Helen’s body was found.

The next day, Tiernan told Christodulas at Jones Beach that the final impediment to their marriage had been removed. The children had been turned over to relatives. Emma McGowan of the West Side Nursery School was notified that her services would no longer be needed, but the woman took note of Tiernan’s uneasiness. Later she noticed a picture in the paper of a badly injured boy who had been found in the Long Island woods. Irene Roggeveen, a social worker who listened to Helen Tiernan’s story, called Detective Frank Naughton at the West Forty-seventh Street police station. Within minutes he arrived on the scene to take the distraught mother into custody. Tiernan changed her story several times. At first she denied any prior knowledge of her children’s disappearance, but then admitted that there had been an attack. A strange man attacked them in the brush, she explained. There was little else to do except run away. But Tiernan did not adequately explain why she had failed to notify the police of this.

Homicide charges were filed, and the prisoner was transported to Suffolk County Jail in Riverhead. George Christodulas was held as a material witness, but was later cleared of involvement in the child murders.

Tiernan, whose own mother died in a state sanitarium, was sentenced to twenty years to life by Justice James Hallinan of the Suffolk County Supreme Court on June 21, 1937. Before she was led away, she asked to see her son, who had been placed in the care of the New York City Child Welfare Board. The request was denied pending approval of the social welfare department.

Tiernan served fourteen years in prison before being paroled on Aug. 27, 1951. A final discharge from jurisdiction was granted in 1964.

Tierney, Nora Patricia, 1920- , Brit. Mrs. Basil Ward left her 3-year-old daughter to play with a neighborhood friend, Stephanie Tierney, while she went to the store. When she returned, her child was missing. Three days later the child’s body was found in a nearby bombed-out house with her head crushed. The only clue to the murderer’s identity was the imprint of a woman’s shoe found near the body.

The playmate’s mother, Nora Tierney, was uncooperative while being questioned. Tierney told Scotland Yard inspector James Jamieson she knew nothing about the child’s disappearance. Jamieson took several pairs of Tierney’s shoes for examination. When he asked for cuttings from her fingernails, she broke down and told Jamieson that her husband had murdered the child with a hammer.

The police soon discovered that James Tierney was elsewhere at the time of the killing. Nora Tierney was charged with the murder and was tried at the Old Bailey in October 1949. She was convicted and condemned to death, but the sentence was commuted to confinement in Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum.

Tinning, Marybeth Roe, 1943- , U.S. Marybeth Tinning and her husband Joseph had lived their entire married life in Schenectady County, N.Y., moving from one two-flat apartment to another. Joseph Tinning worked as a foreman at the General Electric plant in Schenectady. The Tinnings were a nice couple who freely gave of themselves and their time, according to neighbors. But there was something odd behind this facade. In a period of just less than fourteen years, nine of the Tinnings’ children died. All died before the age of five.

The daughter of Ruth and Alton L. Roe, Sr., Marybeth Tinning grew up in Duanesburg, a community fourteen miles outside Schenectady. Tinning was the elder of two children and throughout her childhood and adolescence she claimed to have suffered from isolation and her parents’ neglect and mistreatment. At twenty-three, she married Mr. Tinning, who, unlike his high-strung and outgoing wife, was overly timid. Together, the Tinnings had eight children of their own and had almost adopted a ninth.

The first of the Tinning children to die was Jennifer Lewis, the couple’s third child. Born on the day after Christmas 1971, Jennifer died just eight days later, on Jan. 3, 1972, from respiratory failure and a brain abscess. Her death was the only one attributal to natural causes. On Jan. 20, 2-year-old Joseph “Joey” Tinning, Jr., died. Only days before, Mrs. Tinning had taken him to Ellis Hospital where she told the pediatrician that her son had choked on his own vomit. The doctors could find nothing wrong with the boy and discharged him to his mother’s care a few days later. A few hours later Tinning brought him back to the emergency room dead. She explained that she had put him in the crib for a nap and had found him a little while later lying dead, twisted up in the sheets. She claimed Joey had had convulsive fits.

Four-year-old Barbara Ann, the Tinnings’ first child and the child who lived the longest of any of the Tinning children, became the third fatality. A hospital autopsy concluded that Barbara had died of Reye’s syndrome, partly basing this conclusion on information provided by Tinning. Although no autopsy had been performed on Joey, it was reasoned that he, too, had died of the disease.

The next child born to the Tinnings was also the next to die. Timothy, born on Nov. 21, 1973, died on Dec. 10 of that year. His death and those of the next two children—5-month-old Nathan on Sept. 2, 1975, and 3-month-old Mary Frances on Feb. 22,1979—were attributed to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). This malady would later be erroneously ascribed to the Tinnings’ last three children. As the years passed, the Tinnings’ memories of their two sons Timothy and Nathan became blurred.

There were suspicions about Marybeth Tinning, primarily among the nurses at Ellis Hospital who by 1979, when Mary Frances was born, were more attuned to the signs of child abuse than they had been seven years earlier when the first suspicious death occurred. Although people noted that Mrs. Tinning failed to display normal emotions in the face of these appalling events, no one called for an investigation into the children’s deaths. The circumstances surrounding the death of Jonathan D. Tinning, on Mar. 24, 1980 were markedly similar to those surrounding Mary Frances’ death. The boy was taken to St. Clare’s suffering from a lack of oxygen. A genetic consultant had the boy moved to Boston Children’s Hospital where he ordered a battery of tests. The test results revealed that Jonathan’s birth defects were unrelated to the present difficulty. Before Jonathan was discharged, a Boston physician described him “as wiggly and active a child as you can imagine.” He was returned to Mrs. Tinning with an apnea monitor. Three days later the baby was back in the emergency room having suffered permanent brain damage, a sequence of events almost identical to Mary Frances’ last few days.

With six children already dead, the Tinnings applied to the state adoption service. They were in the process of adopting 31-month-old Michael, when, on Mar. 2, 1981, while adoption officials reviewed the Tinnings’ petition, the boy died of viral pneumonia. Dr. Robert Sullivan, Schenectady’s medical examiner, concurred that the cause of Michael’s death, “showed acute Pneumonia,” but added, “the family history is bizarre.”

On Dec. 20, 1985, another Tinning child, Tami Lynne, died. This last death went beyond the point of coincidence, even for those who still found it difficult to point an accusatory finger at a woman who had suffered so much. An investigation was begun in earnest. No longer were the children’s deaths viewed one at a time by investigators. Dr. Thomas F.D. Oram took into account the deaths of ail nine children, along with the information supplied by Tinning and medical personnel, and concluded that only Jennifer had died of natural causes. Oram also concluded that the remaining children could very likely have died from suffocation. When Oram called a colleague, who was an expert on SIDS, he was told, “There’s only one explanation for all this, and it has to be smothering.”

It was not until February 1987, however, that Tinning admitted killing Tami Lynne. In her thirty-six page confession to police she also admitted murdering Nathan and Timothy, but denied having killed any of the others. With regard to Tami Lynne, she told police, “I did not mean to hurt her. I just wanted her to stop crying.” Of the three she admitted killing, Mrs. Tinning said, “I smothered them each with a pillow because I’m not a good mother. I’m not a good mother because of what happened to the other children.”

At Tinning’s trial, which began in June 1987 in the Schenectady County Court before Judge Clifford T. Harrigan, her attorney Paul M. Callahan claimed that the police had coerced a confession out of Tinning, and argued that his client’s civil rights had been violated through “trickery and deception.” Forensic pathologist Dr. Jack Davies testified that in his view Tami Lynne had died as a result of a rare genetic disorder known as Werdnig-Hoffmann syndrome, akin to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease. Although mention was made of Turning’s confession to killing Nathan and Timothy, the jury was not allowed to know of the five other suspect deaths. Mr. Tinning was not charged, as it was apparent he knew nothing of his wife’s actions. On July 17, 1987, the six-week trial ended with a verdict of Guilty returned against Tinning for committing second-degree murder with a “depraved indifference to human life.” Judge Harrigan sentenced her on Oct. 1, 1987, to a term of twenty years to life in prison.

Toal, Gerard, 1909-28, Ire. Eighteen-year-old Gerard Toal worked as a chauffeur for Father James McKeown. It was a commonly known fact that Toal disliked Mary Callan, McKeown’s housekeeper. Questioned about Callan’s disappearance on May 16, 1927, Toal denied any knowledge of the woman’s whereabouts. No progress was made in the case until months later when a new housekeeper discovered dismantled parts of a woman’s bicycle in Toal’s room. When confronted, he insisted that he had stolen them. Police continued to be suspicious that the parts belonged to Callan’s bicycle which had disappeared on the same day she had.

In April 1928, Toal was dismissed by McKeown. Toal claimed to be headed for Canada but was arrested ten days later for theft in the town of Dundalk. A closer investigation of the priest’s home yielded more bicycle parts and women’s clothing. When Callan’s decomposed body was found in a water-filled quarry nearby, Toal was arrested and charged with murder.

Toal was tried in Dublin in July 1928. The judge advised against a verdict of manslaughter and Gerard Toal was found Guilty of murder. He was hanged on Aug. 29, 1928.

Toole, Otis Elwood, See: Lucas, Henry Lee.

Toppan, Jane (Nora Kelley), 1854-1938, U.S. Born Nora Kelley in Boston in 1854, mass murderer Jane Toppan may have had a genetic claim to insanity. Toppan’s mother died when she was an infant, and her father cared for her and her siblings until he too went insane. He was found one day trying to sew his eyelids shut and was sent to an insane asylum. The children went first to live with their grandmother but were later sent to an orphanage. Jane was adopted by Mr. and Mrs. Abner Toppan in 1859. She grew up to be an attractive, apparently normal, and bright young lady. However, when she was jilted by her fiance she was devastated, and she tried twice to kill herself. She ended a several-year period of seclusion by attending a Cambridge, Mass., nursing school.

When a patient who was in Jane’s care and not seriously ill, suddenly died, she was questioned about the incident and although no report was made, she was discharged from the hospital staff. Without ever finishing her training, Toppan became a private nurse in dozens of New England homes, gaining the confidence of those she cared for.

In 1901, one of Toppan’s patients, Mattie Davis, died. Three other members of her family died shortly thereafter. The trusting family insisted each time that she stay to tend the remaining members. However, when Captain Gibbs, a Davis family relative, returned from a sea voyage to find his wife dead, he became suspicious. The police were called, and several autopsies were performed. In each case, it was determined that the death had been caused by morphine poisoning.

Toppan was traced to New Hampshire, but not before she had murdered another Davis relative. Protesting her innocence, she was returned to Massachusetts and charged with murder. As the investigation of her past began, dozens of the bodies of people she had cared for were exhumed and it was discovered that all had died of morphine and atropine poisoning. The atropine counteracted the constriction of the victims pupils so that morphine poisoning would not be suspected. It was also discovered that Toppan had obtained large quantities of the drugs over the years using forged prescriptions.

While Toppan was in jail, a psychologist, Dr. Stedman, visited her. Eventually she told him she had killed over thirty of her patients. (The actual number is probably closer to 100.) On June 25, 1902, Jane Toppan went on trial. When Dr. Stedman testified that she was suffering from an incurable form of insanity, Jane denied his diagnosis, claiming she was completely sane and always knew what she was doing. She was sent to the Taunton State Asylum for the Criminally Insane where she died in 1938 at age eighty-four.

Totterman, Emil, b.c.1875, U.S. Born in Finland and decorated for heroism at the Battle of Santiago during the Spanish-American War, Emil Totterman was convicted of the December 1903 murder of Sarah Martin and spent the next twenty-five years in prison. There was some doubt that Totterman, a sailor at the time, committed the slashing murder, but he was convicted and sentenced to the electric chair on Mar. 2, 1904, because his luggage was found in the dead woman’s room. His death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment on July 25, 1905.

Except for an escape from a work farm on Aug. 20, 1916, Totterman was a model prisoner. In his years at Sing Sing, he enthusiastically involved himself in the mechanical trades and iron-working, and was designated the official steeplejack, painting the high chimney whenever needed and placing the flag on a high pole on holidays. On Dec. 24, 1929, Totterman received a Christmas pardon from Governor Franklin Roosevelt. Through the cooperation of the Furnish consulate, he was able to relocate and reestablish himself in his native land.

Tracy, Ann Gibson, 1935- , U.S. On Nov. 14, 1960, cocktail waitress Ann Tracy could no longer stand the infidelities, lies, and torment of her lover, Amos Stricker.

Stricker was a wealthy building contractor who had carried on an affair with Tracy for several years. However, he still saw other women and taunted her with stories of his other affairs. As they were lying in bed together, she shot him dead.

Tracy confessed and was tried and convicted of second-degree murder. Sentenced for life to the Corona Woman’s Prison, she still protested that she loved him.

Trebert, Guy, prom. 1959, Fr. Guy Trebert worked as a paint sprayer at a garage in Paris. On the evening of Mar. 15, 1959, he met a young woman by the name of Arlette at a movie theater. Arlette was not particularly interested in Trebert, and when she went to the country on Mar. 26 to visit her two children, she did not inform Trebert of her departure. On her return she found a number of notes from Trebert demanding that she call him immediately. They met once more and Arlette drove with Trebert to the forest of St. Germain. On Apr. 5, her body was found strangled and mutilated.

Trebert was brought to trial for the murder of Arlette in November 1962. Three women testified that Trebert had taken them to the forest at St. Germain also. He had attacked one of the women with a metal tool, and had attempted to strangle two of them while having intercourse with them. Trebert was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Treffene, Phillip John, d.1926, Aus. In the early part of the twentieth century, stealing gold was prevalent enough on the Kalgoorlie goldfields of western Australia to warrant the formation of a special police squad to combat it. In May 1926, two members of the Goldfields Detection Force, John Joseph Walsh and Alexander Henry Pitman set out on bicycles to investigate reports of an illegal gold treatment plant. The Force acted independently and it wasn’t unusual for them to be out of touch on an investigation for days at a time. When Walsh and Pitman did not return by May 10, however, searchers were sent out after them.