Unruh, Howard, 1921- , U.S. Born and raised in Camden, N.J., Howard Unruh had a normal, uneventful childhood. He was a good student and graduated high school during the early stages of WW II. Unruh was drafted into the army and served with an armored division. In basic training he became a sharpshooter and his fellow GIs noticed that he had a fascination for weapons. He would spend hours each night sitting on his bunk taking apart his rifle and putting it back together again. Unruh never took advantage of weekend passes and was never seen in the company of women. He preferred to remain within the confines of his barracks and occupy himself reading his Bible or cleaning his rifle.

Religion had been deeply rooted in Unruh since childhood. He had attended church regularly, gone to Bible class, and read the Bible each day at home. Unruh continued to carry his Bible with him through battle after battle as his armored unit fought its way up the boot of Italy in 1943. Unruh by this time was a machine gunner in a tank turret. In the following year, Unruh’s unit, part of General George Patton’s Third Army, helped to liberate Bastogne in the bloody Battle of the Bulge. Throughout these war years, Unruh kept a diary in which he wrote daily his private thoughts. A fellow GI, who later became a New York policeman, sneaked a look at Unruh’s diary and was horrified to view its contents. Unruh had recorded the death of every German soldier he had killed, the hour and the place he had killed them, and how they appeared in death after he had shot them.

Yet the Army looked up to Unruh as a hero, and before receiving his honorable discharge at war’s end, he was awarded several commendations for his heroic service during battle. There was no hero’s welcome for Howard Unruh when he returned to Camden, however. He was just another soldier, among millions, returning to civilian life. Unruh announced to his parents that he intended to become a pharmacist and, to that end, he took some refresher high school courses and then enrolled at Temple University in Philadelphia. Unruh continued his Bible classes and there met the only girl he ever dated. The relationship was only a mild flirtation and quickly ended.

This brief affair left Unruh embittered. By 1949, he was considered the neighborhood recluse. He became more withdrawn and seldom spoke to his parents, keeping to his room. The only preoccupation that made him joyful was maintaining his collection of weapons, which he had begun after his military discharge. Unruh set up targets in the basement of his parents’ home and practiced his marksmanship each day.

Unruh then began to take offense at off-handed comments made by neighbors. In his mind these became terrible insults, and he suffered what doctors later termed acute paranoia and schizophrenia. He started another diary, or a hate list, wherein he jotted down every imagined and real insult made by neighbors and friends. No grievance was too small to record. This diary was no less exact than the one he had kept in the service.

His next-door neighbors, the Cohens, were particularly annoying to Unruh. Once, while taking a short-cut through the Cohen backyard, Mrs. Cohen had yelled at him: “Hey, you! Do you have to go through our yard?” When the Cohens gave their 12-year-old son a bugle which he practiced daily, Unruh looked upon this as a personal offense against him, as if the neighbors had purposely awarded their son this noisy instrument to annoy him. The list of names and those who offended Unruh grew and grew, and after each offense Unruh wrote the abbreviation “retal,” meaning “retaliate.”

At first Unruh tried to shut out the world that offended him, rather than attack it. He built a high wooden fence around the tiny Unruh back yard. With his father’s help, he built a huge gate that was locked against the intrusions of the outside. Unruh’s room was another haven where he took refuge. Here the young man kept a 9mm German Luger, which he had purchased for $40, several pistols, a large quantity of ammunition, a knife and a machete, both kept razor sharp by their owner.

Unruh’s shaky world collapsed on Sept. 9, 1949. He came home at 3 a.m. that morning to find that someone had stolen the massive gate he and his father had labored so long to erect. Local pranksters had done the deed, but to Unruh everyone living was responsible for this unforgivable insult. Unruh was up all night, staring at the ceiling of his room, seething with hatred. He decided to take revenge. At 8 a.m. he sat down to a breakfast prepared by his mother. He stared at her strangely and would later admit that she was to be his first victim. He had to kill her to spare her the grief he would bring upon the family through his homicidal plans. Unruh went to the basement, then returned, eyes glaring at her, walking toward her menacingly. His mother ran from the house to a neighbor where she blurted her fears about her unstable son.

Going to his room, Unruh loaded his Luger and another pistol, pocketing these weapons, along with a knife. He gathered up several clips of ammunition for both guns and filled his pockets. He walked outside and scrambled over the fence instead of going through the gaping area where the gate had been. At 9:20 a.m., Unruh stood in the doorway of a small shoemaker’s shop owned by John Pilarchik. The cobbler, who had just recently finished paying off the mortgage for his shop, was busy working on children’s shoes. Pilarchik looked up to see Unruh, someone he had known since boyhood. He stared in disbelief as Unruh pulled out the Luger and fired two bullets into his head. Pilarchik pitched forward dead onto his work bench.

Unruh then stepped next door, into the barbershop owned by Clark Hoover who had been cutting Unruh’s hair since he was a little boy. Sitting on a small plastic horse in the shop was 6-year-old Edward Smith, whose mother and 11-year-old sister stood nearby. Without a word, Unruh raised his Luger and shot the boy dead and then pumped two more bullets into the startled Hoover. He ignored the screams of Mrs. Smith and her daughter who rushed forward to cradle the dead child. Unruh looked at both of them but strangely did not fire his Luger. With a vacant stare, he wheeled about and headed for the corner drugstore which was owned by the Cohen family, the people he hated most.

James Hutton, Unruh’s insurance agent, stepped from the drugstore. “Hello, Howard,” he said affably.

“Excuse me,” Unruh said in a monotone. He leveled the Luger at Hutton and fired twice. The insurance agent toppled dead to the sidewalk. Cohen, who saw Unruh shoot Hutton through the window of his shop, raced upstairs to warn other members of his family. Unruh entered the drugstore, inserted another clip into the Luger and then plodded up the stairs after his mortal enemy. Upstairs, Unruh saw no one about. He suspected that the Cohens were hiding and when he heard a noise in a closet he fired a bullet through the closet door. He opened this to see Mrs. Cohen sagging to the floor. He sent another bullet into her head. Cohen and his son slipped out a window and walked along the second-story ledge of the building, scrambling to a nearby roof.

Unruh went into another room of the Cohen apartment and saw Cohen’s elderly mother desperately calling police on a phone. He fired twice, killing her. Then he spotted Cohen and his son scrambling across a sloping roof and he leaned calmly from a window and fired a bullet that slammed into Cohen’s back, causing him to slide off the roof and crash to the pavement below. Unruh carefully leaned further out the window and fired straight down at Cohen, sending another bullet into his back, although the man was already dead. The Cohen boy had by this time slid down to the edge of the roof and was clinging to its edge, screaming. Unruh glanced at him but did not shoot him. He walked back downstairs and went outside.

He found Alvin Day, a passerby, kneeling at the body of James Hutton, trying to help a man who was already dead. Day looked up to see the muzzle of Unruh’s Luger poking into his face. Unruh fired twice, killing Day, a man he had never met before this moment. Reloading the Luger, Unruh began to leisurely stroll across the street. A car was idling at the corner, its driver waiting for the light to change. Unruh walked up to the car and stuck the Luger through the window, shooting the female driver dead. He then fired at and killed the woman’s mother who was in the back seat of the car, along with her young son.

Unruh then began walking down the street. He spotted a truck driver getting out of the cab of his truck a block away. Taking careful aim, Unruh shot him in the leg. By then panic had gripped the entire area. The maniac in the streets was shooting anyone he encountered. The manager of a supermarket quickly locked the front doors and told his customers to lie down on the floor. So did the manager of a bar which Unruh approached. As bar customers huddled on the floor, Unruh tried the door and found it locked. He fired twice, trying to blow away the lock but it held. He moved on, seemingly unconcerned.

Going into the tailor’s shop next door, Unruh found the place empty. Tom Fegrino, the proprietor, was not present but Unruh heard a noise in the back room. He pushed back a drape to see Mrs. Fegrino cringing behind a chair. “Oh, my God, please don’t,” she pleaded. Unruh said nothing as he sent two bullets into her, killing her instantly. Stepping outside, Unruh looked about at the now empty street. The only persons present were those whom he had already killed. Neighbors and passersby had rushed into houses and shops and had locked themselves inside against the random rage of the lunatic. Unruh looked up to see 3-year-old Tommy Hamilton staring down at him. He fired once, killing the boy.

Walking to a nearby house, Unruh entered it by the back door which he found unlocked. Inside the kitchen, he found Mrs. Madeleine Harris and her two sons. The older son, a courageous youth, saw the gun in Unruh’s hand and dashed forward, driving his shoulder into the body of the tall killer. Unruh fired twice, wounding the youth and his mother. He then stood over these two fallen victims who squirmed in pain. He leveled the Luger at them but, oddly, decided not to end their lives. He turned on his heel and walked once more outside.

Police sirens wailing from squad cars could be heard in the distance. Unruh increased his pace as he walked back to his home where he went to his second-story room, barricading the door and reloading his Luger. He waited patiently as police surrounded his house. He looked out his window at them without firing. His identity was by then known and had been reported to Phillip Buxton, editor of the Camden Courier Post. Buxton obtained Unruh’s listed phone number and took a chance, calling the killer.

Unruh picked up the phone and one of the strangest phone conversations in the annals of murder then occurred.

“Hello,” Unruh said in a calm voice.

“Is this Howard?” Buxton inquired.

“Yes, this is Howard,” Unruh replied. “What is the last name of the party you want?”

“Unruh.”

“Who are you and what do you want?” Unruh asked politely.

Buxton was diplomatic: “I am a friend and I want to know what they are doing to you.”

“Well, they haven’t done anything to me yet,” Unruh said in an even voice, as if he were chatting with an old friend. “But I am doing plenty to them.”

“How many have you killed?”

“I don’t know yet—I haven’t counted them, but it looks like a pretty good score.” (Thirteen persons had been shot to death by Howard Unruh within twelve minutes.)

“Why are you killing people, Howard,” Buxton asked, trying to control his own passions while writing down the murderer’s every word.

He was greeted by silence. After some moments, Unruh replied in a low voice: “I don’t know. I can’t answer that yet—I’m too busy. I’ll have to talk to you later.” He hung up.

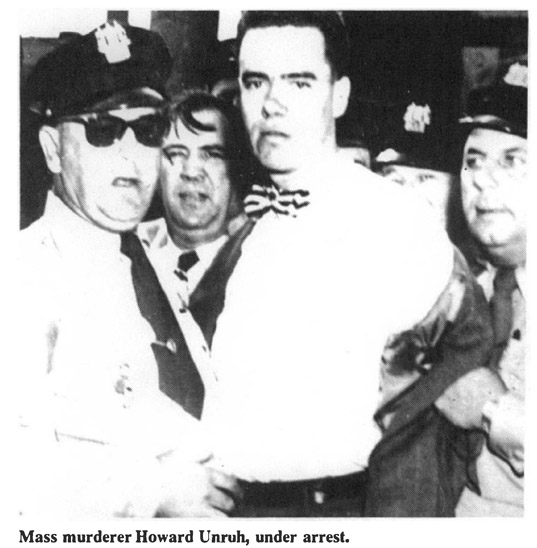

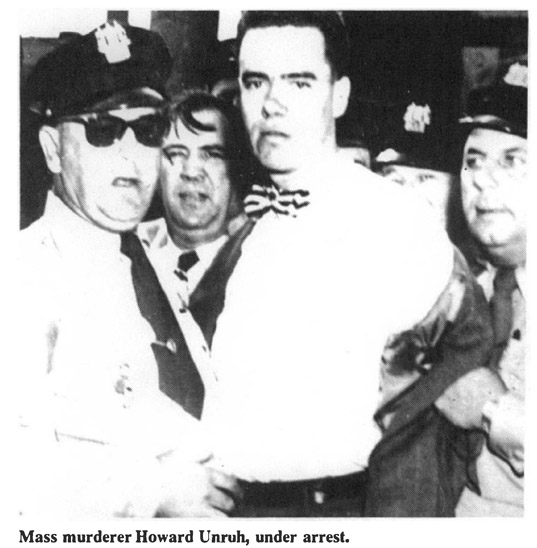

At that moment tear gas cannisters fired by police outside smashed through the glass of the bedroom windows and exploded inside, filling the room with eye-searing gas. These were followed by fusilades of bullets that smacked into the walls of Unruh’s room, chipping the plaster. After a few minutes, Unruh took down the barricade in front of his door and walked downstairs and outside. He put his hands slowly into the air at a command barked by a police officer. Dozens of guns were trained upon him.

Detectives rushed forward, manhandling him, manacling his large hands. Detective Vince Connelly, sickened at the sight of the bodies in the street nearby, stared at Unruh and said: “What’s the matter with you? Are you a psycho?”

Howard Unruh lifted his head indignantly and snapped: “I am no psycho! I have a good mind!”

More than twenty psychiatrists who examined Howard Unruh disagreed. They believed him to be hopelessly and criminally insane. The mass killer was never brought to trial but sent to the New Jersey State Mental Hospital for life. He had no remorse for his brutal, unthinking murders. In one interview with a psychiatrist, Unruh stated: “I’d have killed a thousand if I’d had bullets enough.”

Urich, Dr. Heinz Karl Gunther (AKA: Dr. Henri Urich), d.1960, Mor. A high-ranking official of the SS in Nazi Germany, Dr. Heinz Karl Gunther Urich, was captured by the French near the end of the war. While serving time in a French prison, Urich was offered the chance of joining the French Foreign Legion in North Africa with the rank of medical major and serving out his sentence. The fact that he would be a commissioned officer in the French forces eliminated the possibility of his being tried for war crimes committed in France. Within months after he arrived in Morocco, Urich managed to get a discharge from the Foreign Legion and became the director of a local hospital owned by a mining company. By the time he married Rose Ascensio in 1948, the doctor had changed his name to Henri Urich. Through the marriage, Urich gained a teenage stepdaughter named Liliane with whom he fell in love.

On June 28, 1960, Police Commissioner Ali Mamoud read an obituary notice in the newspaper concerning the death of 22-year-old Liliane Urich. She had died, the notice read, in Hannover, Ger., following an operation. The commissioner was aware of Mrs. Urich having health problems, but the death of his daughter Liliane caught him by surprise. Upon investigation of the doctor’s house, police found that Urich had left town three days ago and requested a three-month leave of absence from the hospital. In investigating the disappearance, police questioned Liliane’s boyfriend who said that Urich did not approve of him and discouraged the girl from seeing him. In conversation with a neighbor of the Urichs’, police found postcards and a letter from the doctor, detailing his daughter’s demise. She had a brain tumor, the doctor wrote, and she died almost immediately following surgery. The neighbor said that she was surprised that Urich had written to her because usually Mrs. Urich did the writing.

Police inquiries to Germany revealed that Liliane had never been admitted to the Hannover hospital and there was no death certificate on file. Unexpectedly, Urich returned to his Moroccan home on July 8 and repeated the story about the tragic tumor for the police. Ali Mamoud also asked him about the houseboy, who had not been seen in a few weeks. The doctor said he had been fired. The Moroccan police received further information from German authorities that contradicted the doctor’s story. On Aug. 10, officials sought to question Urich again, but found him dead in a chair. He had shot himself in the head. On a table was a note dated July 15 saying goodbye to his wife and his daughter Monique. Upon further investigation of the house, police discovered the bodies of Mrs. Urich, Liliane, and Monique underneath the garage floor. Police found the houseboy, who said he had been paid by the doctor to keep quiet. He had witnessed the murders, he told police. The shootings occurred after the doctor argued with Liliane, who refused to stop seeing her boyfriend.