Marco survived an earthquake when he was traveling through Central America. Although he felt terror during the earthquake, he seemed to be all right when he returned home. Two years later, however, while riding the train to a play in the city after a stressful day at work, the rumbling of the train caused him to break out in a cold sweat. It felt to him that the earthquake was recurring as the terror returned.

Chapter 1

Readying Your Amazing, Adaptable Brain

Resilience starts with the brain. Most people do not fully appreciate how the physical conditioning of the brain profoundly affects mental health and functioning. This chapter will explore how to optimize your brain hardware, which refers to the size, health, and functioning of neurons (nerve cells) and supportive tissues. Future chapters will then focus on the software, which is the programming—or the learning of resilience skills. To better understand how we can optimize brain hardware, let’s start by getting acquainted with the marvelous structure that is the brain.

Brain Overview

The resilient brain functions at optimal efficiency. It learns, remembers, sizes up problems, follows instructions, plans, executes decisions, and regulates moods. And it does all this relatively quickly, even under duress. The resilient brain also resists and reverses cognitive decline and brain cell death.

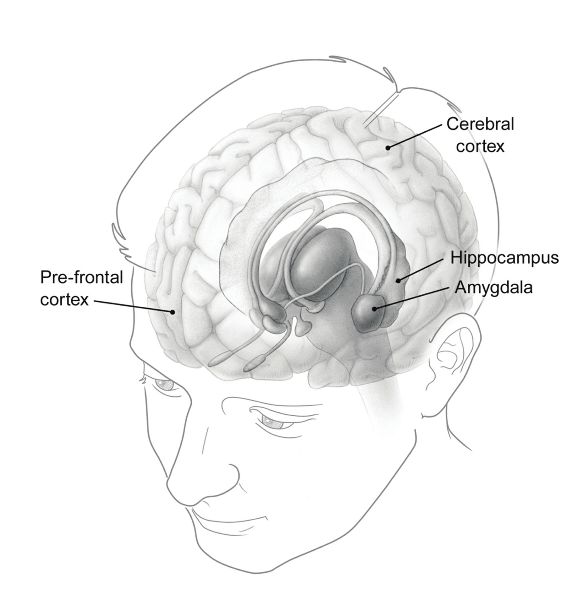

The brain consists of 100 billion neurons, or nerve cells. Each gets input from thousands of others before it fires. The brain is the consistency of Jell-O or tofu, suggesting the need to protect it from physical trauma. We’ll explore four key regions related to resilience (figure 1.1).

The cerebral cortex, the outer shell of the brain, is the seat of conscious thought, logic, and reason. Consciously recalled portions of memories, which are stored in neural networks that spread throughout the brain, primarily reside here.

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) sits just behind the forehead. If the brain is the headquarters of the body (literally corporate headquarters), then the PFC is the CEO. The PFC organizes mental and physical activity and enacts all executive functions. Weaving together what is happening around you with facts and memories stored elsewhere in the brain, the PFC judges, predicts, plans, solves problems, initiates action, and regulates impulses and emotions. The PFC helps to keep excessive emotions in check so that you can function. The PFC typically delays decision making until the decision feels right—that is, when facts and feelings come together. Emotional input comes from the next two structures, the amygdala and the hippocampus.

The amygdala, which takes its name from the Greek word for “almond,” picks up nonverbal cues, especially negative and frightening cues, and immediately trips the stress response and emotional reactions. Thus, another’s facial expression, posture, or tone of voice—or even our own negative memories, sensations, or thoughts—can arouse strong, distressing emotions and cause the physical changes of stress. All of this occurs without conscious thought or words. Thus, we might jump or run away from a frightening situation only to think about it later. The amygdala informs the PFC of feelings and body sensations, without which the PFC’s decision making stalls. It also picks up memories with similar emotional content and sends these to the PFC to further inform decision making. These feelings in turn get woven into new memories, which helps the memories to be retained.

The hippocampus plays a key role in learning and memory. A bigger hippocampus is associated with resilience. This is easy to appreciate when we consider its roles. The hippocampus complements and balances the amygdala. Whereas the amygdala deals in strong emotions and promotes quick and unthinking reactions, the hippocampus deals in cold facts and promotes cool, rational thought.

The hippocampus links the PFC with long-term memory networks. Say you are walking down a path and see a large snake. If acting alone, the amygdala would automatically hit the panic button and send you running. However, the hippocampus calmly pulls up your memories of snakes, which allows the PFC to realize that this snake is different from the rattlers you’ve encountered in the past. In fact, it looks more like a harmless garden snake. It’s as though the hippocampus were saying, “Let’s see the whole picture before jumping.” Once the situation is deemed safe, the hippocampus dampens the amygdala and the stress response that it initiated.

Should you learn a way to cope with a problem, the hippocampus sends this learning to be stored along with appropriate emotion in long-term memory, and it connects this new memory to related memories and beliefs that are already stored. Thus, as you practice an escape plan, you might learn to move deliberately and calmly to a certain exit during a terrorist attack. Practicing with concentration and some emotion (in other words, moderate activation of the amygdala, but not too much) helps you store and retrieve this memory optimally.

The hippocampus gives context and reality to learning. This enables us to know what happened where, how, and when and is very important for the proper storage of traumatic memories. When the hippocampus is properly functioning, the fragments of a memory hang together in a way that makes sense. Thus, a rape survivor can recognize that a rape happened ten years ago. It had a beginning and an end. Although the rape can be remembered, the memory does not intrude with undue emotion as if the rape were happening now. The perpetrator was a man named Joe, but not all men named Joe—so not all men—are untrustworthy. In other words, the hippocampus allows us to store, think about, and talk about memories in an emotionally cool and rational way.

When Things Go Wrong

The amygdala can get us moving quickly, automatically, and with strong emotion. This can be lifesaving. Usually, however, resilience is better served when strong emotions are checked and directed by cool thinking. The hippocampus and PFC temper the intense emotions of the amygdala, allowing thoughtful, rational decision making to prevail. These three structures must work together. However, when this delicate balance is upset, the brain becomes less resilient.

Excessive stress is one factor that can upset this balance. One of the hormones secreted under stress is cortisol. Moderate amounts of cortisol sharpen thinking in the short term. However, excessive amounts disrupt brain function in several important ways.

Overactivates the amygdala. This can lead to excessive anxiety that hinders learning and makes thinking more emotional and negative. The hyperactive amygdala also imprints memories with excessive, intense emotion rather than details. Thus, a threat that triggers a distressing memory might cause you to overreact with excessive fear or the freeze response. The amygdala is typically hyperactive in people with PTSD. This hyperactivity gives traumatic memories their strong emotional charge.

Shrinks or impairs the functioning of the hippocampus, or both. Recall that the hippocampus tempers the amygdala’s response to stress, calmly recalls existing memories when needed (Where was that emergency exit?), and stores traumatic memories in a cool, integrated way.

Disrupts PFC function. When this happens, creative thought, problem solving, emotional regulation, concentration, and the ability to shift attention quickly and effectively are probably degraded.

This story demonstrates how excessive stress can disrupt normal memory storage:

Marco’s overactive amygdala caused the first extremely emotional memory to intrude inappropriately and be confused with the rumbling of the train. An unimpaired hippocampus would have enabled Marco to think, What’s happening today is a totally different time, place, and event.

Aging is a second factor that interferes with optimal brain functioning. The brain typically starts to decline in size and function by age thirty, and, with aging, we usually see a shrinkage that begins with the hippocampus and spreads to the PFC. Similar changes are seen with Alzheimer’s disease, with shrinkage and damage spreading from the hippocampus to other areas of the brain involved in memory, language, or decision making (National Institute on Aging). Declines in the brain due to aging can be slowed and possibly reversed. The same healthy lifestyle strategies that protect the brain against age-related decline also optimize brain functioning and might even lower the risk of Alzheimer’s disease

Two Important Findings

Two intriguing recent findings about the brain give us great hope for improving resilience. First, the brain is plastic (Doidge 2007). This means that it changes structure and function in response to new experiences throughout an individual’s life span in ways that can improve resilience. We now know that new neurons can grow in the hippocampus and other key areas, replacing old ones or those damaged by stress. This growth rate, as well as the size and health of neurons, can be affected by the key factors that we’ll discuss shortly. We also know that neurons can link together, forging new neural pathways as we learn adaptive coping skills. The more we practice these skills, the stronger and more efficient these neural connections become. Conversely, neural connections can deteriorate with disuse, and practicing poor coping skills reinforces maladaptive pathways.

Second, brain health equals heart health (Gardener et al. 2016). What kills the body kills the brain. What keeps the heart healthy keeps the brain healthy. Thus, it is important to

- stay lean (being overweight doubles the risk of dementia; abdominal fat is particularly risky);

- keep blood pressure, blood sugar, total cholesterol, and triglycerides (a type of blood fat) low; and

- keep good (HDL) cholesterol high.

The Eight Keys to Optimal Brain Health

Eight keys work together to optimize brain health: regular exercise; brain-healthy nutrition; sleep; minimizing substance use; managing medical conditions; restricting anticholinergic medications; minimizing pesticides, preservatives, and air pollutants; and managing stress. We’ll take a look at each one in this section, but first consider what these keys accomplish:

- Increase the volume of, the number of neurons in, and the supportive tissue of the brain—especially in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex

- Increase the health and functioning of the neurons

- Reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, which impair the brain

- Clear out harmful proteins that are found with Alzheimer’s disease

- Strengthen the blood–brain barrier, which protects the brain from damaging toxins and inflammatory agents

- Improve mood

- Enhance cognitive function (concentration; ability to learn, remember, and reason; creativity; productivity; and speed of thinking and of switching focus from one situation to another)

Regular Exercise

Many studies document the ways exercise, particularly aerobic exercise, benefit mood and brain function. Exercisers have sharper brains at all ages. Exercise produces master molecules in the brain that normally decrease with stress and aging. These master molecules increase blood flow to the brain, strengthen and grow neurons, increase antioxidants, and prime neurons to learn new coping skills. Exercise particularly seems to grow the PFC and hippocampus. Exercise reduces tension, anxiety, and depression, often as well as prescribed medications do and without side effects, while improving sleep and increasing energy. When started gradually and done in moderation, regular exercise usually strengthens joints and reduces pain. It has been found to even reduce PTSD symptoms.

Most research on this topic indicates it’s best to start by gradually building an aerobic base. A reasonable goal is at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise a week. This might mean thirty minutes of brisk walking, cycling, swimming, or slow jogging five or more days per week. “Moderate intensity” means you can just carry on a conversation as you exercise. If you can’t speak at all, you might be overdoing it. To avoid discouragement, start by doing less than you think you can at a slower pace, increasing exercise time by 10 percent each week until you reach your goal.

Outdoor exercise in the morning can be helpful. Morning workouts seem to help people stick to exercise programs, and ten to fifteen minutes of sunlight a few times a week raises vitamin D levels, which improve brain function in many ways.

You can boost benefits by adding flexibility and strength training—light weights, elastic bands, push-ups, or the like—to your aerobic base. A reasonable goal for strength training is ten repetitions of each exercise two to three days a week. Flexibility exercises, such as stretching, can be done most days to keep limber. You might consider exploring high-intensity interval training, once your physical fitness has improved. This type of training involves alternating bursts of vigorous exercise with periods of easier exercise. Interval training improves many indicators of heart health and brain function in less time than continuous exercise.

Complex motor movements bring additional brain benefits. Yoga, tai chi, dance, racket games, juggling, rock climbing, or playing an instrument all establish beneficial neural pathways. New challenges, such as learning a language, developing a hobby, reading a good book, completing puzzles, taking art classes, or traveling, also sharpen the brain.

Brain-Healthy Nutrition

A growing number of studies have shown that a Mediterranean-style diet greatly promotes longevity, brain health, and sharper brain function. This type of diet emphasizes fruits and vegetables (fresh or frozen), fish, whole grains, nuts and seeds, beans and peas, and olive oil; moderate amounts of poultry, eggs, and low-fat dairy; and minimal red and processed meats (beef, lamb, pork, hot dogs, sausage, salami, and other lunch meats), butter, stick margarine, cheese, pastries and sweets, and fried or fast food. Here are some other helpful nutrition guidelines.

Maximize the intake of brain-friendly antioxidants. These protect neurons from damage caused by stress and aging. Antioxidants are found in colorful fruits and vegetables—such as leafy green vegetables, berries, tomatoes, apples, oranges, or cantaloupe—and even pale plants, such as pears, white beans, green grapes, cauliflower, and soybeans. In your diet, emphasize fresh or frozen plant foods. Antioxidants are also plentiful in nearly all spices, such as turmeric, cinnamon, oregano, ginger, pepper, garlic, and basil. Store spices in a cool, dark place, and use them within two years of purchasing. Chocolate contains antioxidants and is also beneficial—if eaten in moderation.

Aim to eat at least two to three servings of fish per week, totaling at least eight ounces. The omega-3 fatty acids in fish are critical components of the brain’s neurons. These fatty acids improve brain health and function, while reducing depression and possibly even stress in traumatized people. Restrict the amount of fried fish you consume, since frying adds unhealthy fats and cancels the omega-3s’ benefits. Fish oil supplements can be helpful. Look for supplements that provide five hundred to one thousand milligrams of the omega-3s DHA and EPA daily, as opposed to total milligrams of fish oil.

Choose good carbohydrates. The brain functions best with a steady supply of blood sugar. Plant foods, as nature packages them, contain fiber, which slows the absorption of sugars and provides that steady supply of sugar. Conversely, processed carbohydrates (such as white flour, sweets, sugary sodas, white rice, or processed cereals) result in spikes in blood sugar, followed by a rapid fall in blood sugar. This is why a candy bar might provide a quick energy surge, followed by fatigue, hunger, and slip in mood. Processing also strips plants of antioxidants and other nutrients. So emphasize whole grains and fresh or frozen plant foods, which will also help you stay lean.

Choose good fats. Saturated fats, especially when eaten with refined carbohydrates, impair brain health and function—even after a single meal. Think of a hamburger on a bun made from refined white flour, with a sugary soda and dessert. A single such meal can impair brain function. Replace saturated fats, and the trans fats found in processed and fast foods, with healthy fats found in plant foods. Healthy fats include olive oil, avocados, nuts, and canola oil. Also, choose low- or no-fat, instead of full-fat, dairy products.

Hydrate. Neurons are mostly water. Mood and mental functioning can be impaired by consuming too little liquid. Assuming normal eating, you will likely need to drink nine to sixteen cups of liquid a day to properly hydrate—or even more if you are large or active, even in cooler conditions. Drink throughout the day. Water is a great choice. Two cups before meals promotes leanness. Unsweetened fruit juice contains antioxidants and can be taken in moderation (perhaps half a cup a day). You can tell if you’ve been drinking enough liquid if the urine that collects in the bottom of the toilet bowl from the first void of the day is the color of pale lemonade.

Spread out protein intake throughout the day. Start with a good breakfast, which sharpens the brain, promotes a sense of fullness throughout the day, and promotes leanness. Protein can come from low- or no-fat unsweetened yogurt, egg whites, poultry, seafood, beans, nuts, peanut butter, or protein powder.

Eat enough, but not too much. If you follow the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans you can get the nutrients you need for optimal brain health and functioning. These guidelines are consistent with the Mediterranean-style diet and mostly avoid calorie-rich, nutrient-poor foods. The food choices in the Mediterranean-style diet also tend to reduce anxiety and promote calmness. The combination of consuming needed nutrients but not overeating appears to help neurons rest and regenerate.

Minimize added salt and sugar. These are typically found in processed foods.

It’s easier to follow these guidelines if you grow your own produce, purchase fresh or frozen produce, and prepare your own meals. Restaurant foods, fast foods, and processed foods typically are high in salt, sugar, and unhealthy fat. Visualize a plate where meat is a small side dish, and the rest of the plate is filled with plant foods, and a brain-healthy meal plan will be easy to follow. You won’t have to worry about what not to eat when you focus on what to eat.

Resilient Eating

The 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans specifies the number of servings individuals who are nineteen years or older need each day from the various food groups in order to feel and function their best. The guidelines below are quite consistent with the Mediterranean-style diet and apply to most adults. The greatest need for the average American is to increase servings of fruits and vegetables. (The MIND diet is another type of Mediterranean-style diet that has been found to be brain healthy. To read more about it, visit http://www.newharbinger.com/39409.)

* Adapted from 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. See https://www.ChooseMyPlate.gov for more detailed guidelines and a wealth of practical information about nutrition and physical activity. Except for dairy, the amounts above depend on age, sex, and level of physical activity. The amounts needed assume you expend 1,600 to 2,400 calories per day. Males who are younger or more active, for example, might need to consume amounts in the higher range, or sometimes more.

Sleep

Can you remember that last time you got a good night’s sleep and the world seemed brighter and people more pleasant? Sleep energizes and refreshes the brain. A good night’s sleep also reduces oxidative stess and helps clear toxins from the brain. Yet most of us do not fully appreciate how even a little sleep deprivation significantly impairs mental health and performance. Most adults require between 7 and 8¼ hours of sleep per night to feel and function their best. Less than that amount worsens mood and functioning. The harmful effects of sleep shortage, which are particularly pronounced with six hours of sleep or less per night, include

- brain shrinkage (sleep deprivation is a stressor that stimulates cortisol secretion, which seems to particularly impact the hippocampus);

- impaired ability to remember, make decisions, problem solve, settle traumatic memories, and perform tasks requiring speed and accuracy;

- increased stress-related conditions, such as depression, anxiety, PTSD symptoms, and substance-use disorders; and

- medical problems, ranging from weight gain to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, ulcers, and autoimmune disorders, all of which impair brain function.

Three Principles of Good Sleep

There are three principles to be aware of that can help you get good sleep: amount, regularity, and quality. In terms of amount, strive for seven to eight hours of sleep per night, or even a little more. Sufficient sleep usually helps people accomplish more during the next day. Regarding regularity, try to go to bed and arise at the same time, even on weekends. Consistency helps the brain regulate sleep cycles and improve sleep. Should you need to change your schedule, try to shift the time you go to bed by less than one hour from one night to the next. The quality of your sleep is important, as this list of variables to consider highlights:

- Light and noise disrupt sleep even when we don’t think they do. Blue light from electronic devices is particularly disruptive. Shut down light sources at least an hour before going to bed. Ensure that light and noise are blocked in the bedroom (try curtains or shades that block morning light, eyeshades, earplugs, or a white-noise machine).

- Give yourself an hour or more to wind down before going to bed. Turn off arousing media. Instead try soothing music, relaxation, pleasant reading, or journal writing.

- Napping can partially offset sleep loss. Successful nappers regularly nap in a quiet, dark place for 20 to 120 minutes. If napping interferes with your ability to sleep at night, avoid it to consolidate nighttime sleep.

- Avoid a heavy meal or excessive fluid intake before bedtime. Digestion can override the brain’s tendency to fall asleep, and a full bladder can wake you up. Try not to eat anything for at least four hours before retiring. If hunger awakens you during the night, a small snack of protein and carbohydrates before bedtime might help you maintain sleep (for example, warm milk and honey, yogurt, cereal and milk). Other small snacks that might be useful include a banana, walnuts, almonds, an egg, avocado, tuna, and turkey.

- Early-morning exercise helps regulate sleep rhythms. Tai chi and yoga usually help. Avoid exercising within two hours of bedtime.

- Cut back on caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol, which interfere with sleep, especially when taken in the hours before bedtime. Caffeine and nicotine are stimulants. Alcohol facilitates falling asleep, but then it has a stimulant effect.

- If possible, get off shift work, which is linked to a variety of mental and physical disorders, including shorter and more disturbed sleep. If shift work is necessary, try to move from earlier shifts to later shifts, and stay on the same shift for as many weeks as possible to help the brain regulate sleep rhythms.

- Challenge distressing thoughts that heighten arousal. Such thoughts might include, It’s awful if I don’t get a good night’s sleep. I’ve got to get a good night’s rest. Instead, try to think, This is inconvenient but not the end of the world. If you don’t fall asleep within twenty minutes of going to bed, simply get up and do something relaxing. Go back to bed when you feel sleepy.

- Seek professional help for conditions that interfere with sleep. These include sleep apnea and other sleep disorders, mental disorders (such as depression, anxiety, PTSD, and substance-use disorders), thyroid conditions, heartburn, arthritis, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, respiratory conditions, pain, and urinary problems.

- Avoid sleeping pills as a general rule. These can have adverse side effects and can actually increase insomnia in the long term. Try nonpharmacological steps first, which are generally at least as effective.

Minimize Substance Use

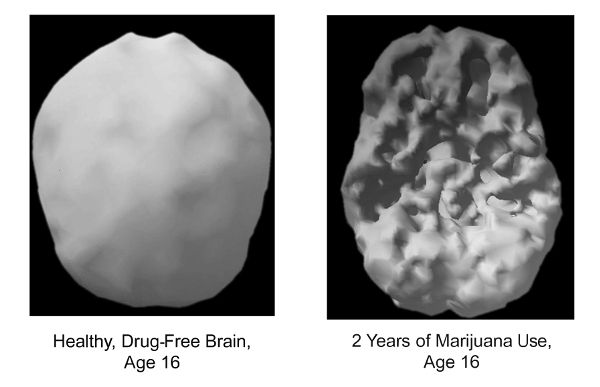

Nuclear brain imaging reveals the effects of substance use on brain function years before structural damage is apparent. Figure 1.2 shows the brains of two sixteen-year-olds. The brain on the left is a healthy, drug-free brain in which all areas are functioning well. The brain on the right is the brain of a sixteen-year-old who has been using marijuana for two years. A similar scalloping or Swiss-cheese effect is seen in the brains of young people after just a few years of excessive use of alcohol, cigarettes, inhalants, cocaine, or methamphetamines.

Figure 1.2: The effects of substances on brain function (Amen 2005)

Figure 1.2: The effects of substances on brain function (Amen 2005)

Consider the following facts.

Smoking greatly increases the risk of depression, anxiety, and panic attacks. It also impairs memory and increases the risk of dementia. Like tobacco, marijuana decreases blood flow to the brain and impairs memory.

Alcohol intake is inversely correlated with resilience. It may even shrink the brain when taken regularly in small amounts described as “mild” or “moderate” drinking.

Excessive caffeine can interfere with brain function by restricting blood flow to the brain, and it can cause insomnia, anxiety, and excess arousal. Up to four hundred milligrams of caffeine a day—about the amount in four cups of coffee—appears to be safe for most healthy adults. This amount can easily be exceeded by drinking energy drinks, caffeinated sodas, or more than four cups of coffee.

Manage Medical Conditions

There are numerous medical conditions that affect brain health and function.

Sleep apnea typically occurs when the airway closes up during sleep, depriving the brain of oxygen. It is marked by snoring, the stoppage of breathing, and loud gasps for air as people partially awaken during the night to breathe. The pattern of blocked breathing and partial awakening can repeat itself scores of times throughout the night. One awakens deprived of both sleep and oxygen, feeling mentally sluggish and tired, and often has problems with memory and mood. Sleep apnea increases the risk of heart attack, stroke, high blood pressure, headaches, and nightmares. Most people with sleep apnea have depression, and sleep apnea is very common in people with PTSD. Fortunately, it is very treatable, and proper treatment often reduces the psychological symptoms that accompany it. Discuss with your doctor treatment options that keep the airway open. Losing five to ten pounds of weight and limiting alcohol, sedatives, sleeping pills, and muscle relaxants might also help.

Elevated cholesterol levels in the blood can sometimes cause depression. Exercise, proper eating, stress management, and medications can help.

Thyroid disorders are called the great mimic because they can cause or worsen so many symptoms of stress-related conditions (including anxiety, depression, or PTSD) as well as unexplained symptoms such as sluggishness, sleep problems, and weight gain. Problems can arise when the hormone thyroxine is slightly above or below normal ranges. Typical blood tests can measure levels of thyroxine in the blood. However, an inexpensive thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) test is more sensitive. TSH, which is secreted by the brain, stimulates the thyroid gland to secrete thyroxine. If, for example, thyroxine is in the low normal range but TSH is elevated, this indicates that the brain is trying to stoke a sluggish thyroid. Elevated TSH is associated with decreased blood flow to the brain, especially in the prefrontal cortex, as well as memory and concentration problems. Get a TSH test if you experience a mental disorder, memory loss, elevated cholesterol, or other unexplained symptoms. If you are taking thyroid medication, monitor TSH and thyroxine levels to ensure that the dosage is correct. Avoid smoking, which can interfere with proper thyroid functioning.

High blood pressure can cause microbleeds in the brain. Blood pressure can usually be lowered through a combination of brain-healthy eating, exercise, sleep, and possibly medication.

Type 2 diabetes increases the risk of cognitive impairment, dementia, cardiovascular disease, and hippocampal shrinkage. Reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes by following the guidelines in this chapter. If you have diabetes, keep it under the best control possible through proper treatment and blood sugar monitoring.

Gum disease can produce toxins that enter the bloodstream, leading to inflammation and harm to the brain. This is an argument for regular brushing, flossing, and dental cleanings; if you have gum disease, get professional treatment. Avoiding tobacco, getting sufficient sleep, drinking lots of water, and eating a quarter cup of yogurt containing live bacteria each day might also help reduce the risk of gum disease.

Restrict Anticholinergic Medications

Acetylcholine is an important chemical messenger in the brain. Even with occasional or short-term use, anticholinergic medications block acetylcholine and have been linked to brain shrinkage, slowed activity in areas associated with memory, and dementia (Nelson 2008). These medications include antihistamines, sleeping pills, over-the-counter sleep aids, tranquilizers, muscle relaxants, ulcer medications, and tricyclic antidepressants. Ask your doctor or pharmacist if your medications are anticholinergic. If so, discuss using the smallest dose for the shortest amount of time possible. Or ask about switching to an alternative medication or trying a nonpharmacological treatment.

Minimize Pesticides, Preservatives, and Air Pollutants

Pesticides, preservatives, and air pollutants are toxic to neurons. Pesticides are found on produce and are brought into the house when we walk through outdoor areas treated with weed killers. Growing your own produce, thoroughly washing store-bought produce, buying organic produce, and restricting the use of processed foods reduces pesticides and preservatives. Reduce exposure to air pollutants by avoiding tobacco smoke, by recirculating air in your car if you are stuck in traffic, and by using good filters (such as in the furnace) in the home.

Manage Stress

As we’ve discussed, excessive or chronic stress can disrupt brain health and function. It can also sap energy and joy. Fortunately, there are many effective ways to manage stress. Much more to come about this later.

Activity: Make Your Plan for a Resilient Brain

Many people have reported that making and sticking to an exercise, nutrition, and eating plan were among the most helpful aspects of resilience training. Make a health plan that you can maintain as you work through this workbook and beyond. Describe your plan below.

Exercise: Aim to get at least 150 minutes of aerobic exercise (such as brisk walking or cycling all or most days) per week. You might also add strength and flexibility training to further sharpen the brain.

Sleep: I’ll get hours of sleep per night (a little more than I think I need), going to bed at and getting up at .

Nutrition: Eat at least three times per day, selecting brain-healthy choices from the dietary guidelines in the section “Resilient Eating.” Using the form in appendix A, make a sample menu that is consistent with these guidelines: Does your plan provide sufficient servings from each food group in order to ensure you’re getting needed nutrients? Are you varying foods within each food group, which also helps ensure you’re getting all the needed nutrients? (The federal government has an excellent, free online tool to help plan and assess how well your dietary and physical activity choices compare with recommended amounts. Visit https://www.ChooseMyPlate.gov and then locate SuperTracker.)

Activity: Track Your Progress

Using the form in appendix B, track your progress over a fourteen-day period; then make helpful adjustments and continue to follow your plan as you move through the workbook.

Activity: What Else Might Help?

After reviewing this chapter, consider the following, and then make a list of any factors that might be impairing your ability to feel and function at your best:

- Unhealthy substance use: Note that abruptly stopping substance use might make the symptoms of psychological problems more troubling. You might wish to find a program, such as Seeking Safety, that gently helps one reduce substance use while preparing to address PTSD symptoms (see recommended resources).

- A physical exam: This can help you rule out or treat medical conditions.

- Sunlight: We need sufficient sunlight or high-intensity artificial light to feel our best.

- Recreation and lifelong learning: These activities lift mood and improve brain function.

Once you’ve made your list, indicate the steps you plan to take to address these factors. Filling in the chart below can shed light on helpful steps.

| What’s interfering with my health, mood, or functioning? | What would help? | What steps will I take? | When will I take these steps? |

|---|---|---|---|

Conclusion

This chapter explored eight ways to strengthen the brain hardware, readying the brain for the resilience skills in the following chapters. You’ll likely find that following the recommendations in this chapter will also improve your mood, energy level, and mental functioning. Give yourself time to put a healthy brain plan in place. When you are ready, proceed to the next two chapters, which will help you manage your body’s response to excessive stress, or arousal.