Chapter 2

Regulating Arousal: The Basics

This chapter and the next one will help you regulate your body’s response to stress so that you can feel and function at your best. We’ll explore some very simple and effective skills that will reset your nervous system so that your stress levels will be neither too high nor too low. Let’s start by looking at what happens in your body during difficult times.

Understanding Stress and Arousal

When the brain perceives a threat, it triggers changes in the body called the stress response, or just stress. These changes prepare us to move—to fight or flee. The brain becomes sharper. Stress arousal increases, meaning muscles tense and blood pressure, heart rate, breathing rate, and blood sugar increase to get more fuel to the muscles. Ideally, the body moves, expends energy, and then returns to normal. Problems occur, however, when arousal is dysregulated. Usually this means that arousal rises too high or remains elevated, though arousal can also drop below optimal levels. Dysregulated arousal is common to the stress-related conditions mentioned earlier, such as depression, anxiety, panic attacks, PTSD, substance-use disorders, and problem anger.

Have you ever felt too aroused to think or talk straight? Conversely, have you ever felt too numb or exhausted to do so? Excessive stress changes your biology. Understanding this will help you to normalize dysregulated arousal and know how to manage it. Let’s start by understanding optimal arousal levels.

Optimal Arousal: The Resilient Zone

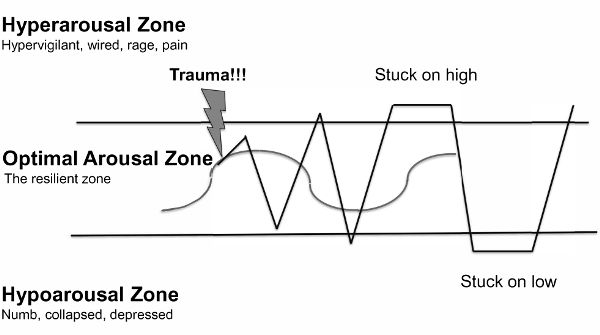

Figure 2.1 depicts optimal levels of arousal, sometimes called the resilient zone. The horizontal lines indicate that arousal is neither too high nor too low. When arousal levels are in this zone, we feel and function at our best. All parts of the brain and the organs of the body are working harmoniously. Breathing and heart rates are slow and rhythmic. Muscles are relaxed, or just tense enough to function well. We feel grounded—secure, centered, whole, connected to our bodies, and aware of bodily sensations.

Figure 2.1: Optimal arousal zone (Heller and Heller 2001; see also Porges 2011, Miller-Karas 2015, and Ogden, Minton, and Pain 2006)

Figure 2.1: Optimal arousal zone (Heller and Heller 2001; see also Porges 2011, Miller-Karas 2015, and Ogden, Minton, and Pain 2006)

In this zone, arousal fluctuates smoothly and without extremes because there is balance among the branches of the nervous system. Thinking and behavior tend to be flexible and effective. Challenges are typically met with appropriate emotions and social engagement. Thus, we might reach out to others—seeking or offering support, resolving differences, or negotiating with threatening people without being overcome by extreme emotion. This is the ideal place to be when confronting challenges. However, extreme stress can bump us out of the resilient zone, as shown in figure 2.2.

Hyperarousal Zone

Trauma or other emotional upheavals can overwhelm our coping capacities. These events can occur at any time in life and can be particularly disruptive when they occur in the early years. A single severe event or series of events can bump us out of the resilient zone.

If we cannot think or talk our way out of difficulty, as we are hardwired to do in the resilient zone, then the brain automatically kicks us to the hyperarousal zone. This is a condition of extreme fight or flight, the purpose of which is to prepare us to physically battle something or someone or run away to safety. Heart and breathing rates become rapid and erratic. Muscles become overly tense. Perspiration increases to cool the body. Preoccupied with survival, regions of the brain concerned with logic and language go off-line, and alarm centers become overactive. We might say that in this zone we are too wired to think or talk straight. Negative thoughts (such as I can’t take it, I’m a loser, and others described in chapter 5), worries, and concentration problems are common in this zone.

Regions of the brain that give us a sense of being one with our bodies also go off-line. We might begin to lose awareness of normal bodily sensations—or we might become overly sensitive or troubled by intense sensations such as pounding heart, heavy breathing, or pain. Strong emotions, such as anger, irritability, anxiety, and even panic are common, as are nightmares and sleep disturbance.

Hyperarousal can serve a protective function during an emergency, but it is problematic when the brain’s alarm stays on and the symptoms of extreme arousal persist.

Figure 2.2: Hyperarousal and hypoarousal (Heller and Heller 2001; see also Porges 2011, Miller-Karas 2015, and Ogden, Minton, and Pain 2006)

Figure 2.2: Hyperarousal and hypoarousal (Heller and Heller 2001; see also Porges 2011, Miller-Karas 2015, and Ogden, Minton, and Pain 2006)

Hypoarousal Zone

What if you’ve been on high alert for so long that you feel exhausted or numb? Or what if the normal action of the fight-or-flight response is thwarted? For example, a child may not be able to run away or fight back when being abused, and trying to do so might incite further violence. When fight or flight is blocked or leads to exhaustion, the brain is hardwired to elicit hypoarousal, a state of numbness, exhaustion, shutting down, immobilization, or collapse. Sometimes playing dead is the best way to survive, or numbing might temporarily protect one from emotional or physical pain. However, when you’re stuck in hypoarousal, you feel disconnected from self, others, and your body. You’re too shut down to think or talk straight. Outwardly, you might exhibit a slumped posture, a downward gaze, glazed eyes, weakness, a collapse of normal defenses, or a flat or depressed expression. Some people even feel as if the world is not real, or that they themselves are not real.

Some people alternate between hyper- and hypoarousal. Others, prior to transitioning to the hypoarousal zone, will experience alert immobilization, in which the arousal alarm stays on as one also experiences exhaustion.

What You Can Do

The more you practice the simple skills below, the more likely you will be to stay in the resilient zone or return to it readily when stressed. All of these arousal regulation skills involve tracking, which is paying very close attention in a curious and nonjudgmental way to what you sense in your body. Tracking brings back online those areas of the brain involved in regulating arousal, thinking effectively, and restoring a sense of connection to one’s body.

Breathing Skills

We’ll start with three short but effective calming techniques involving breathing. When we’re under stress, our breathing often becomes rapid and shallow as we tighten muscles in the throat, chest, and abdomen in preparation for fight or flight. Even subtle shifts in breathing can result in less oxygen reaching the brain, heart, and extremities—along with a shift in blood acidity. Scores of symptoms can result from these stress-induced changes, including anxiety, panic attacks, a feeling that you or your surroundings are not real, exhaustion, headaches, sleep disturbance, unsteadiness, racing heart, and concentration problems. As breathing calms, the ability to think, speak, remember, and perform improves.

The Reset Button

When you find yourself running around, and your mind is racing, this two-minute technique provides a refreshing, restful pause.

- Sit comfortably erect in a chair, with feet firmly on the ground, and hands resting unclasped in your lap. Close your eyes if doing so is comfortable. Otherwise, let your eyes drop downward to about forty-five degrees, so that you are looking at the floor.

- Be aware of your breath. Follow it and notice what happens in your body as you breathe. You might notice the rib cage expand and a feeling of energy or lightness on the in-breath. On the out-breath, you might notice a feeling of settling and comfort. When agitated water settles, it becomes very clear. Similarly, as you pause to let your mind settle in your breath, it too becomes clear.

- As thoughts, worries, or plans arise, just notice them without judgment, and gently bring your mind back to the breath and the sensations in the body.

- Feel a sense of connection to yourself and others.

Calm Breathing

Abdominal breathing has been a mainstay of arousal regulation for centuries. Even small, stress-induced shifts in normal breathing can profoundly affect mental states, medical symptoms, and functioning.

- As before, sit comfortably erect in a chair, feet flat on the floor, with hands resting in your lap but not touching. Let the back of the chair support your back.

- If it is comfortable, close your eyes (or drop your gaze) and sense what your body is feeling now. Notice, without judging, areas of the body carrying stress or tension.

- Now take a moment to consciously relax the muscles of the mouth, jaw, throat, shoulders, chest, and abdomen. Place your hands over your navel. Imagine that the stomach fills with air on the in-breath, so that your hands rise, and empties of air on the out-breath, so that your hands fall. Upper-chest breathing is inefficient and stressful, so keep the chest and shoulders relaxed and still. Breathe naturally and comfortably—no gasps or abrupt movements—for one to two minutes.

- Track what happens in your body.

Tactical Breathing

This adaptation of calm breathing, developed by Lieutenant Colonel Dave Grossman (Grossman and Christensen 2004), has been widely taught to members of high-risk groups, such as the military and police.

- Relax your shoulders and upper body.

- Breathe in through the nose for a count of four, expanding your belly.

- Hold the breath for a count of four.

- Breathe out through the lips for a count of four.

- Hold for a count of four.

- Repeat steps 2 through 5 about three times. Track what happens in your body.

Activity: Breathing Skills

Try either the reset button, calm breathing, or tactical breathing seven times a day for a week. Try the skill when awakening, before going to bed, before meals, and two other times during the day. Keep a log for how effective each attempt was physically and emotionally, using ratings from 1 (not calming at all) to 10 (very calming).

Seven days will give you an idea of how well a particular breathing skill works for you. Appendix C is a log sheet for resilience strategies. Photocopy it (or download it from the website for this book, http://www.newharbinger.com/39409) and use it to keep a record of the resilience strategies you try. After the seven days, look for patterns in your log. Did its effectiveness improve with practice? Was its effectiveness greater at certain times of day? Going forward, how might you see yourself practicing and applying this skill? You might wish to continue practicing the same breathing skill or experiment with a different one.

Body-Based Skills

Most of psychology works in a top-down way. That is, language and logic are used to calm the body. When we are bumped out of the resilient zone, however, it is often more effective to work from the bottom up. In this way, we first calm the body and the lower regions of the brain that are concerned with mobilizing the body for stress. In the process, we regain composure and feel safer and more secure. Once arousal returns to the resilient zone, regions of the brain concerned with logic and language come back online so that we can think and talk more effectively. Body-based master clinicians Patricia Ogden (Ogden and Fischer 2015; Ogden, Minton, and Pain 2006), Bessel van der Kolk (2014), Peter Levine (2010), and Elaine Miller-Karas (2015) have pioneered the body-based skills that follow. These skills have been taught around the world and, because they are so simple and effective, have even been used in developing countries following natural disasters. Try them and see if you think they are powerful. All of the body-based skills emphasize tracking, which is sensing the inner world of the body in a curious, nonjudgmental way. This helps to bring the structures of the brain that regulate arousal back online and to restore a sense of connection to one’s body and self.

Movement

The stress response is designed to get us moving and expending energy. Movement strategies help to release the bottled-up energy of stress. They also help to counter the immobilization of the hypoarousal state. Besides these exercises, the slow movements of yoga, tai chi, and qigong, coupled with tracking, are also excellent ways to return to the resilient zone.

Kneading: Squeeze or knead one arm, up and down, noticing sensations as you go. Track sensations both on the surface and deep within the arm. Experiment with different types of touch—firmer or softer pressure, quick or slow, deep or shallow, soothing or mechanical. After going up and down one arm several times, pause and compare the feelings in the arm you just squeezed versus your other arm.

Moving the arms: Gently and slowly stretch your arms up toward the ceiling as you breathe in. As you breathe out, slowly and gently return your arms to your sides. Track the sensations—such as flexibility, muscles relaxing, lightness, circulation, and so on—in the arms, shoulders, and hands. Then track what is happening in the rest of the body.

Gesturing: Think of your favorite gesture that you associate with pleasant feelings. The gesture might be smiling, waving hello, slowly rubbing your earlobes or forehead between the eyebrows, positioning the hands palms up in a welcoming gesture, folding your arms across your body with one hand resting on the side of your body and the other on the opposite arm (self-hug), placing a hand over your heart, throwing a ball, or some other pleasant movement. Think of one, take a deep breath, relax your muscles, and then make the gesture. Track what happens with your breathing, heart rate, muscle tone, facial expression, posture, and other visceral sensations.

Resistance: While standing, place one foot behind the other, feet firmly on the ground. Bend the knees, feel the strength in your legs and core, and push slowly but strongly against a wall. Track: sense how your body feels as you actively move. Take your time.

Changing the posture: Emotional upheaval or trauma might have taught you to look down, hunch your shoulders, and slump over. Try to exaggerate these movements and track what happens as you do. Now notice what happens when you straighten your spine, lift your chin, expand your chest, and look confidently ahead. Track how that feels. Go back and forth between these two extreme postures. Notice how changing your posture in pleasant ways gives you a sense of control over your inner experience.

Grounding

Grounding anchors us safely and securely in the present moment. Remember the importance of tracking, which pleasantly restores that sense of connection to self and body.

Standing grounding: Stand with feet shoulder-width apart, firmly and securely planted. Unlock your knees, soften your feet, and track sensations in your feet and legs. Slowly rock forward, sensing weight over the balls of your feet. Then rock backward, sensing the weight shifting to your heels, and return to center. Slowly rock to the right, sensing the weight on the outer portion of the right foot and the arch of the left foot. Notice the opposite sensations as you rock to the left. Return to a secure balance point, and pause to track.

Now sense how it feels to stand tall, with relaxed shoulders, straight spine, uplifted chin, and expanded chest.

And now imagine that your legs are the trunk of a tree, and roots grow deeply into the ground from your feet, wrapping around rocks and roots and giving you a sense of security. You might imagine that your arms are branches swaying in the breeze, while your trunk is firmly rooted. You might even slowly move your arms upward and outward before bringing your arms back to your sides. Don’t forget to track, noticing things like breath, heart rate, and muscle tension. Notice subtle, pleasant shifts in emotions.

Grounding in the body: Place one hand on the middle of your back so that the fingertips almost reach the spine. For a few moments, sense your rib cage move as you breathe, and track sensations, thoughts, and emotions as you do so. Now place the other hand over your heart, experimenting with different kinds of touch—firm, soothing, and so forth—until you sense which kind of touch feels best. You might move your hand from the back and place it over your heart, your belly, or elsewhere on the body that feels pleasant. Take your time to track sensations, emotions, and thoughts.

Resourcing

A resource is anything that helps you feel a pleasant feeling, such as joy, peace, comfort, love, confidence, or eager anticipation (Miller-Karas 2015). A resource can be a favorite person, place, memory, or pet; a cherished value or inner strength; an accomplishment; a favorite hobby or activity; God; or imagining a pleasant time in the future. Write down three of your favorite resources. Pick one and describe it in writing in as much detail as possible, using all five senses, inner bodily sensations, and emotions. Read your description slowly and track what happens in your body as you curiously hold this resource in mind. Take your time.

Activity: Use a Body-Based Skill

Practice a body-based skill involving movement, grounding, or resourcing. Practice it twice a day for at least three days to give it a fair trial, and record your experiences on a log sheet, such as appendix C. If your experience was positive, try practicing the skill longer, or experiment with another body-based skill to increase the number of tools in your coping toolbox.

Conclusion

The skills we explored in this chapter can be very effective for regulating the nervous system. Contrary to most psychological approaches, these skills work by first calming the body so that the higher regions of the brain can come back online and function better. Master them so that you can use them before difficult events, when you are under pressure, or after a difficult time when you need to recover. In the next chapter we’ll explore two additional skills that are very effective for regulating arousal in a bottom-up fashion.