Chapter 6

Mindfulness

Cognitive restructuring is helpful for nearly everyone who tries it. However, there are times when reason alone is insufficient to soothe troubling emotions. For these situations, there is a complementary skill that, like cognitive restructuring, helps reduce emotional and physical distress across a wide range of conditions. This skill is called mindfulness, and it works in a very different way.

In 1979 Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn introduced mindfulness to Western medicine. As the director of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical School (now the Center for Mindfulness), he was sent patients with diverse medical conditions who were not responding to traditional medical treatments. Treating them with what he called mindfulness-based stress reduction, he found that psychological and medical symptoms of suffering decreased by 30 percent, irrespective of patient diagnoses. Since that time, mindfulness training has been taught in psychology and medical centers, universities, and even prisons throughout America and around the world. And evidence has shown that mindful people seem to have a better ability to manage strong negative emotions.

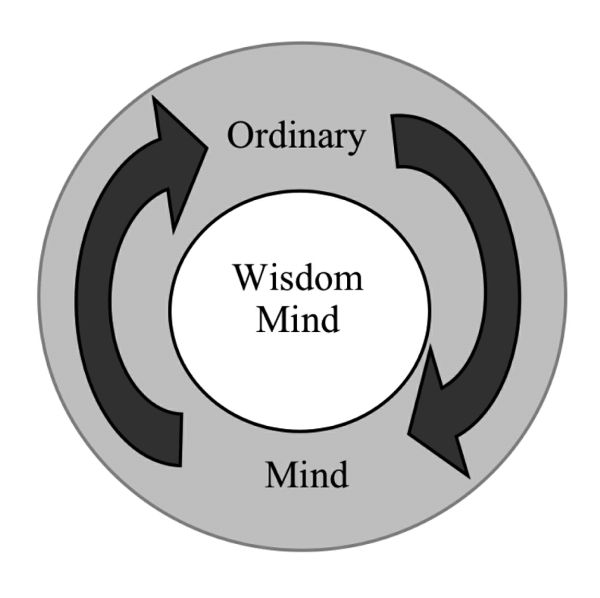

Although mindfulness comes to us from Eastern psychology, it easily blends with nearly everyone’s perspective. Mindfulness assumes that each of us is of two minds (see figure 6.1). The wisdom mind, sometimes called our true happy nature, is who we really are at our core. The wisdom mind is kind, wise, calm, patient, cheerful, and hopeful—the traits we associate with resilience. The ordinary mind surrounds and camouflages our wisdom mind, keeping us from experiencing our true happy nature and causing much suffering. Swirling, racing, effortful thoughts (signified by the arrows in figure 6.1) characterize the ordinary mind, which obsesses, worries, plans, ruminates, stews, hurries, judges, resists pain, and fights against the way the world is (Why do I have this pain? I can’t stand it. I have to stop it. What if it doesn’t end?). Such thoughts lead to anxiety, depression, anger, greed, and other troubling emotions. When we say that someone is beside herself (with worry, anger, and so forth), we are saying that she is pulled away from her true happy nature and locked in a battle in the ordinary mind. In the mindfulness view, the thoughts are the problem. The more we engage or fight the thoughts, the more distressed we become. The mindfulness solution is to simply acknowledge distressing thoughts and then go underneath them, returning to our peaceful, natural happy state. A thought is just a thought. It’s not necessarily true, and it needn’t be given excessive attention.

Figure 6.1: The dual nature of the mind

Figure 6.1: The dual nature of the mind

Cognitive restructuring counterpunches, or fights back, against the distortions that lead to emotional distress. For example, one might counter the thought I’m inadequate by marshaling evidence for competence. Yet sometimes fighting thoughts can create more tension. Can you imagine what might happen if instead of fighting against the distressing emotion, you simply sat with that emotion and soothed it, much like a loving parent would embrace and soothe an injured, crying child? Eventually the ache diminishes, and the child returns to play. This suggests how mindfulness will teach you a new way to respond to distress.

The Mindfulness Attitudes

In certain Eastern cultures, the word for “mind” is the same as the word for “heart.” Mindfulness training cultivates attitudes of the heart. Here are six of the most essential attitudes.

Compassion: This means sorrow for the suffering of others, plus the desire to help and to soothe the pain. In the context of mindfulness, “compassion” also means that we feel the same way toward our own pain. All that is done in mindfulness brings kind, gentle, friendly awareness to each moment of suffering—and to each pleasant moment as well.

Curious, nonjudgmental equanimity: In the West, we typically dislike pain. We often judge and label it as bad and use painkillers to try to escape it. This battle typically increases the pain. In mindfulness practice, we simply observe the pain without judging it as good or bad. We simply watch it the same way we might watch a pleasant emotion. This stance—changing only our response to pain—often helps to diminish the intensity of the pain.

Acceptance: This means simply acknowledging the way things are in the moment, without immediately trying to fix, change, or fight them. The attitude of acceptance says, “Whatever I feel is okay. Let me feel it.” In dropping the battle with emotions, the emotional intensity often shifts. Not that you try to make this happen. You simply notice what shifts.

Vastness: The wisdom mind is broad and deep enough to take in your suffering. You might liken the wisdom mind to the vast ocean. From the depths of the ocean, the wisdom mind watches suffering rise and fall like the waves on the surface. The ocean absorbs the suffering without being changed by the suffering. Likewise, you can embrace suffering without fear or tension, knowing that it comes and goes, and you are vast enough to cope with it.

Good humor: Much of our suffering comes from being overly serious. We approach mindfulness with an almost playful, cheerful attitude.

Beginner’s mind: Experts assume they already know, and so learn little. Like a child, the beginner is open to learning from new experiences. With mindfulness, we remain open to new attitudes and to experiencing our true happy nature. We approach mindfulness practice with the attitude that it might be beneficial, rather than pessimistically assuming it won’t be.

The Mindfulness Training Sequence

Imagine that you have chronic pain and are beginning an eight-week mindfulness training. You are first asked to slowly eat a raisin and do nothing else. You might notice that thoughts flood your mind: What does a raisin have to do with easing my pain? I don’t like raisins—Mom put them in my oatmeal. I hate oatmeal. I wonder what’s for lunch. I have things on my to-do list. These thoughts pull you out of the moment to the extent that you don’t experience eating the raisin. If you simply notice the thoughts without judging them, and gently bring your attention back to eating the raisin, you might notice rich flavors and other sensations you usually miss when hurriedly eating raisins. You might also notice that you are more relaxed when you pay attention to the physical sensations of eating—just calmly noticing without judging or reacting with strong distressing emotions. In other words, you are beginning to experience the essence of mindfulness practice.

Next, you’re taught mindful breathing. Without actually trying to make anything happen, you practice simply watching yourself breathe. With beginner’s mind, you notice that each breath is unique. You notice changes in your body as you rest in the breath. When the mind wanders, or thoughts arise, you practice simply noticing, without judging, and gently escorting attention back to the breath. You might notice how calming it is to rest in the breath and to cease fighting against thoughts that come and go.

Then the body scan skill teaches you to simply notice what the body is sensing, without judging particular sensations as good or bad. You’re taught to breathe into body regions, and then gently move awareness around the body in a curious way. You continue to practice responding with equanimity to thoughts that arise, returning awareness to the body. Both mindful breathing and the body scan teach you to rest in the body, beneath the distressing thoughts.

These and other skills are blended into the powerful meditation that follows, sitting with distressing emotions, which is a new way to respond to intense negative emotions and to take care of yourself. If this meditation seems useful, you might continue to practice it, or seek additional training (see “Mindfulness” in the recommended resources).

Activity: Sitting with Distressing Emotions

This meditation teaches us to be calm and nonreactive in the presence of whatever emotions arise, be they pleasant or unpleasant. Rather than trying to fight or suppress pain, we turn gently toward pain with kind awareness—relaxing and softening into it. Softening our response changes the way we experience pain. It is recommended that you practice this meditation for thirty minutes or more each day for at least a week.

- Assume the meditator’s posture, sitting comfortably erect, with feet flat on the floor and hands resting comfortably in the lap. The spine is straight like a stack of golden coins. The upper body is relaxed but comfortably erect, sitting in graceful dignity like a majestic mountain. (The dignified mountain is secure and unchanged, despite the changing conditions around it.) Allow your eyes to close. Let your breathing help you to settle into your peaceful wisdom mind.

- Remember especially the attitudes of compassion, acceptance, good humor, and vastness. Remember that you are already whole. Use the beginner’s mind as you explore a new way to experience feelings.

- Be aware of your breathing. For several minutes let your belly be soft and relaxed, paying attention to its rise and fall as you breathe in and out. Notice the movements and sensations in the abdomen, chest, nose, throat, and rib cage. For example, you might notice the rising and stretching of your abdomen on the in-breath, or the air flowing in and out of your nostrils. Just notice, without judging or trying to make anything happen. Just allow whatever is happening to happen as you rest in the breath, noticing with kind curiosity. And when thoughts arise, just notice them, then gently, patiently, and repeatedly bring awareness back to your breathing.

- Be aware of any feeling in your body, any sensation as it comes and goes, without judging or trying to change it. For example, you might notice where your leg meets the chair, or where your hands rest in your lap. Pick a region, such as the belly. Breathe into and out of that region. Imagine that your mind is resting in that region. Just notice what you sense, without judgments, such as I don’t like discomfort. Simply notice sensations with kind acceptance and allowance. Sometimes sensations change when we bring kind awareness to them—they come and go. Nevertheless, just watch what happens without trying to make something happen. When you are ready, take a more intentional in-breath, breathe out, and then let attention dissolve from that area as you bring attention to another region of your body, such as your chest. Notice what you sense in the region around your chest. If there is any discomfort or anxiety, simply notice that. Breathe into that area. Think of your breath as carrying kindness and acceptance to that area. Breathe into and out of that area, just noticing the changing sensations in that area. When you are ready, take a more intentional in-breath, breathing into that area. On the out-breath, let awareness of that area dissolve as you bring awareness to another area of your body, such as your hand. Breathe into and out of that area, just noticing what you sense in that area. When you are ready, take a more intentional in-breath, and as you breathe out let awareness shift to your body as a whole.

- Whenever you find your mind wandering, congratulate yourself for noticing this. This is just what the ordinary mind does. Remember that thoughts are just thoughts and not who you are, and bring your awareness gently back to breathing and sensing your body. You are not trying to stop your thoughts, only to notice them calmly and then gently escort awareness back to your breathing and body.

- And now recall a difficult situation, perhaps involving work or a relationship, and the feelings that arise, such as unworthiness, inadequacy, sadness, or worry about the future. Make a space for this situation. Give deep attention to these feelings. Whatever you are feeling is all right. Greet these feelings cordially, as you would greet an old friend.

- Notice where in the body you feel the feelings. It could be your stomach, chest, or throat, for example. Let yourself feel the feelings completely, with full acceptance. Don’t think I’ll tighten up and let these feelings in for a minute in order to get rid of them. This is not full acceptance. Rather, create a space that allows you to completely accept the feelings.

- Breathe into that region of the body with great compassion. Think of fresh air and sunlight entering a long-ignored and darkened room. Follow your breath all the way down through the nose, throat, lungs, and then to the part of the body where you sense the distressing emotion or emotions. Then follow the breath out of your body, until you find yourself settling. You might think of a kind, loving, accepting smile as you do this. Don’t try to change or push the discomfort away. Don’t brace yourself against or struggle with it. Just embrace it without judging it—with real acceptance, deep attention, peace, and the goodwill and kind feelings toward all people that are known as loving-kindness. Let the body soften and open around that area. The wisdom mind is vast enough to hold these feelings with great compassion; love is big enough to embrace, welcome, and penetrate the discomfort. Let your breath caress and soothe the feelings as you would your adored sleeping baby.

- Remember that you are vast enough to embrace the pain with kindness. If you find it helpful, think of loved ones who remind you of loving-kindness—and let that loving-kindness penetrate your awareness as you remember that difficult situation. Simply notice what happens to the feelings without trying to change them.

- When you are ready, take a deeper breath into that area of the body, and as you exhale, widen your focus to your body as a whole. Pay attention to your whole body’s breathing, being aware of the wholeness and the vast, unlimited compassion of the wisdom mind that will hold any pain that comes and goes. Expand your attention to the sounds you are hearing, just bringing them into awareness without commenting or judging. Simply listen with a half smile. Feel the air against your body; sense your whole body breathing. Notice all that you are aware of with a soft and open heart.

- To conclude, say the following intentions silently to yourself: “May I remember loving-kindness. May I be happy. May I be whole.”

- Be mindful of what you are now experiencing. With curiosity and good humor, just notice how your body feels. What emotions are you feeling? Is there calmness, peace, or a feeling of being settled? Are you upset? Whatever you feel, it’s okay. Just let yourself be aware.

If you are interested in exploring mindfulness further, you might read 10 Simple Solutions for Building Self-Esteem (Schiraldi 2007), from which this meditation was adapted, or consult other mindfulness aids in the recommended resources section.

Activity: Sitting with Core Beliefs

Cognitive restructuring, described in chapter 5, taught you a way to uncover and dispute distressing core beliefs. This can often be very helpful. However, core beliefs typically are embedded in our minds in the early years and might be difficult to completely soothe with logic. Mindfulness teaches a different way to deal with distressing core beliefs that relies more on the heart than the head.

Let’s say that your core belief is I’m inadequate. This is normal. Nearly everyone feels that way at times. No one likes to feel that way, of course. So you might get locked in a battle against that thought, thinking I’m not inadequate. That’s too painful a thought. I can’t let anyone know I feel that way. I’ll become so competent that no one will ever accuse me of being inadequate. Or you might simply keep thinking about reasons why you are capable. Perhaps the core belief originated when you were criticized severely as a child. As an adult, the battle continues, along with much distress.

Mindfulness assumes that the thought I am inadequate is just a thought that we fight in the ordinary mind. What would happen if you were to simply allow that thought to be without fighting it? What would happen if you were to notice where in your body you sense the emotion linked to that thought and embraced the emotion with compassion? Can you see that this approach changes only your response to the situation? Paradoxically, this approach cultivates a security that allows us to grow, unencumbered by the exhausting mental battle.

For this activity, select a troubling core belief, such as I’m inadequate, I’m unlovable, or I’m worthless. Rather than fighting thinking with thinking, drop the fight against the core belief. You’ll notice where in your body you experience the core belief (or more correctly, the associated emotion). You’ll breathe into the discomfort without judging it, and then you’ll let awareness of the discomfort dissolve. As you fail to react emotionally but respond compassionately, the neural pathways associated with negative thoughts and feelings degrade through disuse. Instead you’ll strengthen the pathways associated with the wisdom mind. Practice this meditation for several times over the next few days, and notice what happens.

- Sit comfortably in the meditator’s posture, sitting comfortably erect, with feet flat on the floor and hands resting comfortably in your lap. Breathe softly, resting in the wisdom mind.

- Bring the core belief into kind awareness. Without judging the thought, simply notice where you sense the thought and associated feelings in your body, and breathe into that area with loving-kindness and complete acceptance.

- Occasionally, if it is helpful, mindfully remind yourself:

- It’s just a thought.

- Holding that thought in kind awareness.

- Feeling compassion.

- Keep breathing into the area of the body where you sense the thought. Take your time, breathing into the area until you are ready to release your awareness of that area.

- Take a deeper, more intentional breath into that area. On the out-breath, let awareness of that area dissolve as you become aware of your environment. Or, shift to the smile meditation (this meditation can be found with item 9 at http://www.newharbinger.com/39409).

Conclusion

Mindfulness offers a refreshing alternative to the battles we often fight with our thoughts. Paradoxically, by kindly accepting whatever we feel, we find that the intensity of negative feelings often subsides. The next three chapters offer specific applications for bringing kind acceptance and awareness to difficult circumstances.