Chapter 9

Managing Distressing Dreams

Recurring nightmares are common in people who have experienced emotional upheavals or traumas. For example, even the well-adjusted WWII veterans that I interviewed still struggled with nightmares of liberating the concentration camps decades after the war ended. Many veterans with PTSD still have several nightmares a week decades after returning from combat. You might have frequent, troubling nightmares related to any number of difficult experiences, and this chapter will help you manage them.

Nightmares simply signal that there is memory material that the mind is trying to sort out. Normally, dreams help the brain process and settle distressing memory material. However, for extremely distressing experiences, dreams can get stuck, replaying without change or resolution.

Recurring nightmares disrupt sleep, leaving people fatigued and less effective the next day. They trip the stress response and increase cortisol secretion, which further affect mood, memory, and performance. Many who suffer from nightmares begin to fear going to sleep, resulting in insomnia. The combination of disrupted sleep and the distress caused by nightmares can increase the risk of several stress-related conditions.

Settling Nightmares

Fortunately, there are steps you can take to change nightmares and lessen their negative impact. In this chapter we’ll explore a five-step process that might help you settle your nightmares.

1. Normalize your nightmares. Think of your nightmares as simply distressing memory material that needs to be processed and settled, not avoided. The helpful principle is to bring all aspects of the nightmare into calm awareness, changing both your response to the nightmare and the nightmare itself. It can be reassuring to realize that your nightmares contain themes similar to those of others who have experienced difficult experiences. Dream researchers have described the following common themes in nightmares (Barrett 1996):

- Danger, terror, death, fear of death

- Being chased

- Being rescued

- Monsters (who might chase, harm, or frighten you)

- Revenge

- Being punished

- Being alone

- Being trapped, powerless, helpless, or confused (for example, freezing and being unable to fight back or protect yourself; being unable to find a weapon or the weapon doesn’t work; being lost)

- Physical injury (for example, losing teeth might symbolize losing control or being wounded emotionally)

- Filth, garbage, excrement (might symbolize disgust, shame, loss of dignity or meaning in life, or evil)

- Sexual themes (for example, following abuse one might dream of good or bad sex, shadowy figures, worms, snakes going into holes, blood, shame, disgust, anger, hurting the assailant, being shunned)

- Violence, gore, killing, injury

- Being threatened again by a person or event that harmed you

2. Confide your dreams. Recall from chapter 8 that verbalizing, telling the story in words, helps to neutralize, integrate, and settle difficult memories. In this step, you bring your dream to conscious awareness so it can be processed and completed. You might describe your nightmare to a supportive person or an audio recorder or write about it in a journal kept beside your bed. The goal is to fully describe all the elements of the nightmare so it has a beginning, middle, and end. Relax and describe the following details:

- Facts (What is the setting? Who are the characters? What is happening? What are you doing? What are the symbols and what are they saying?)

- Feelings (What are you feeling?)

- Thoughts (What are you thinking?)

- Sensations (What are your physical sensations?)

3. Rehearse a different, calmer response. For example, instead of feeling terror, you might imagine calming yourself in the dream by kneading your forearm, breathing slowly, and saying to yourself, “This is just a dream. I’m safe now.” Before going to sleep, mentally rehearse this new response so that it is in place should the dream recur.

4. Change the nightmare in any way that feels right. You might give it a new ending. You might imagine finishing business—saying farewell to those who died and seeing them now in heaven, smiling. You might imagine healing the severely injured by moving your hand over injured limbs (anything is possible in imagery). You might see yourself being rescued or protected by good and powerful people. Perhaps you stop and turn toward the monster chasing you and make friends with it. You will know what is needed. The only caution is to not include violence in your new ending, because it does not usually settle nightmares. Write or draw how you want to change your dream; then mentally rehearse the new dream for about fifteen minutes at least once a day for a week.

5. Expect changes in dream content. As you rehearse different responses and changes to nightmares, you’ll likely notice shifts in your dream content. Perhaps your dreams of deceased people now contain assurances that they are well off. Or perhaps your dreams now have more positive outcomes. Maybe you realize you did your best under difficult circumstances and now feel somewhat better or brighter about the future.

An Example of Processing Dreams

The following example demonstrates how nightmares can be processed. This case combines the use of drawing with verbal expression. Art can be a very helpful medium for processing dreams in that it can tap feelings, thoughts, sensations, and even creative solutions that might be difficult to capture initially with words. And once the dream is captured on paper, it is often easier to talk about it “out there” at a distance.

One couple hadn’t slept throughout the night for four years because their otherwise well-adjusted nine-year-old son Jake burst into their room each night, terrified by nightmares. The boy had merely seen a commercial for a scary movie, but he could not be comforted; he had to sleep in his parents’ bedroom with the lights on. When I asked the boy to draw his nightmare, he drew a picture that at first glance didn’t appear too frightening. However, the drawing depicted the scary movie character Chucky (see figure 9.1, and notice the eyebrows and the scars). I asked him how he felt when he looked at the picture. He replied, “Scared, mad, sad.” I asked what went through his mind as he looked at the picture, to which he replied, “I’m not strong; I’m weak. I can’t do anything.” He rated the intensity of those feelings and thoughts as 10 on a scale of 1 to 10.

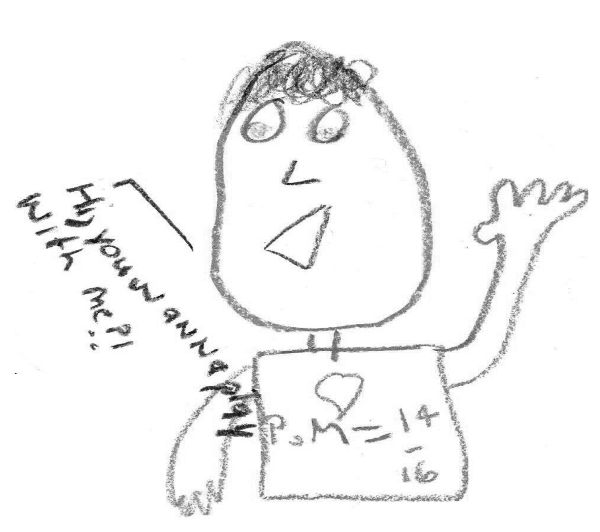

I then asked him to draw pictures of how the dream made him feel in his body, and he drew the figures 9.2 and 9.3. Notice the rating scale for his heart rate in 9.3. I didn’t know what that meant, but it didn’t matter because it made sense to him. Next I asked him to change the dream in a way that felt good. He drew figure 9.4. Notice that the scars are healed and that Chucky is smiling and friendly. In figure 9.5 Jake depicted the way that the new drawing made him feel in his body. In the drawing, he is saying, “Hi, you wanna play with me?!” Jake said he now felt “strong and recharged,” like he could “do almost anything.” I then asked him to think about the new drawing and the new thoughts, feelings, and sensations as we did a calming exercise. After doing this, Jake said he felt great and that he didn’t think the memory was as scary anymore. The ratings of his negative thoughts and feelings dropped greatly.

The next day, his parents called and said, “You won’t believe this, but Jake slept through the night for the first time in four years.” Months later he was still sleeping well.

I often share Jake’s case in my resilience trainings to show that processing nightmares need not be difficult. On several occasions adults have reported that they successfully used the steps outlined in this chapter with their children or themselves.

Figure 9.1: Jake’s drawing of Chucky.

Figure 9.1: Jake’s drawing of Chucky.

Figure 9.2: Jake’s drawing of his emotions.

Figure 9.2: Jake’s drawing of his emotions.

Figure 9.3: Jake’s drawing of his sensations.

Figure 9.3: Jake’s drawing of his sensations.

Conclusion

You don’t need to be a psychologist or an art therapist to try this skill and process your nightmares. It’s not about producing high-quality art; it is about authentic expression of thoughts, feelings, and sensations. Of course, like all other skills in this book, seek an experienced mental health professional if you feel you need additional support.

Before leaving the topic of nightmares, please note that sleep apnea is common among those who experience frequent nightmares. It is thought that apnea starves the hippocampus of oxygen, which interferes with the proper storage of emotionally charged memories. Be sure to get checked for sleep apnea. Treating sleep apnea often reduces nightmares.