If you want to get started with gamestorming right away, you can flip to the collection of games that begins with Chapter 5 and start making things happen in your workplace. But if you want to really master gamestorming, you'll need to learn how to design your own games, based on your goals and more specific to what you want to accomplish.

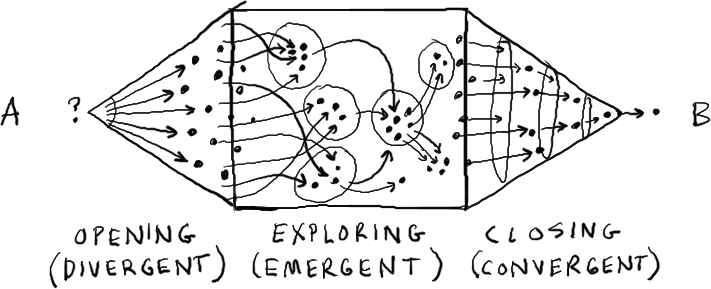

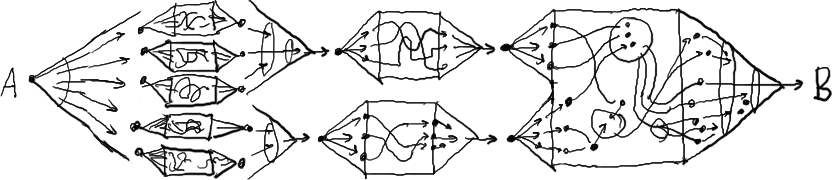

Let's start with this idea. A game has a shape. It looks something like a stubby pencil sharpened at both ends. The goal of the game is to get from A, the initial state, to B, the target state, or goal of the game. In between A and B you have the stubby pencil—that's the shape you need to fill in with your game design.

- Target State:

To design a game you begin with the end in mind: you need to know the goal of the game. What do you want to have accomplished by the end of the game? What does victory look like? What's the takeaway? That's the outcome of the game, the target state. I like to think of the target state in terms of some tangible thing, which can be anything from a prototype to a project plan or a list of ideas for further exploration. Remember, it helps if a goal is tangible; it gives people something meaningful to shoot for and gives them a sense of accomplishment when they have finished. And when they are done, they'll be able to look at something they created together.

- Initial State:

We also need to know what the initial state looks like. What do we know now? What don't we know? Who is on the team? What resources do we have available?

Once we understand the initial and target states as best we can (remember that many goals are fuzzy!), it's time to fill in the shape of the game. A game, like a good movie, unfolds in three acts.

The first act opens the world by setting the stage, introducing the players, and developing the themes, ideas, and information that will populate your world. In the second act, you will explore and experiment with the themes you develop in act one. In the third act, you will come to conclusions, make decisions, and plan for the actions that will serve as the inputs for the next thing that happens, whether it's another game or something else.

Each of the three stages of the game has a different purpose.

- Opening:

The first act is the opening act, and it's all about opening—opening people's minds, opening up possibilities. The opening act is about getting the people in the room, the cards on the table, the information and ideas flowing. You can think of the opening as a big bang, an explosion of ideas and opportunities.

The more ideas you can get out in the open, the more you will have to work with in the next stage. The opening is not the time for critical thinking or skepticism; it's the time for blue-sky thinking, brainstorming, energy, and optimism. The keyword for opening is "divergent": you want the widest possible spread of perspectives; you want to populate your world with as many and as diverse a set of ideas as you can.

- Exploring:

Once you have the energy and the ideas flowing into the room, you need to do some exploration and experimentation. This is where the rubber hits the road, where you look for patterns and analogies, try to see old things in new ways, sift and sort through ideas, build and test things, and so on. The keyword for the exploring stage is "emergent": you want to create the conditions that will allow unexpected, surprising, and delightful things to emerge.

- Closing:

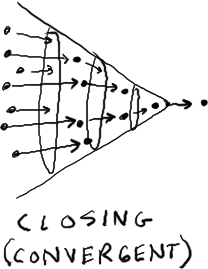

In the final act you want to move toward conclusions—toward decisions, actions, and next steps. This is the time to assess ideas, to look at them with a critical or realistic eye. You can't do everything or pursue every opportunity. Which of them are the most promising? Where do you want to invest your time and energy? The keyword for the closing act is "convergent": you want to narrow the field in order to select the most promising things for whatever comes next.

When you are designing an exercise or workshop, you want to think like a composer, orchestrating the activities to achieve the right harmony between creativity, reflection, thinking, energy, and decision making. There is no single right way to design a game. Every company, and every country, has its own unique culture, and every group has its own dynamic. Some need to move faster than others, and some need more time for reflection.

For example, in Finland, long silences where people consider and reflect on a question before answering are not uncommon. This can feel very uncomfortable if you're not accustomed to that culture. You'll need to do your homework and compose a flow that's right for the group you are working with, and the situation you are working on.

Opening, exploring, and closing are the core principles that will help you orchestrate the flow and get the best possible outcomes from any group. A typical daylong workshop may be filled with many games that can be linked to each other in an infinite variety of ways. Games can be played in series, where the outcomes of one game create the initial conditions for the next.

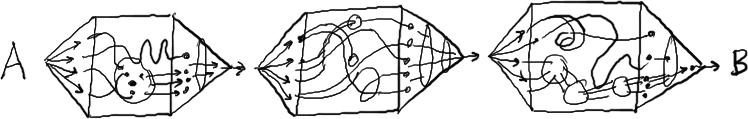

Here's a series where three games are played in a row. Each game has a clear opening, exploration, and closing. The outcome of each game serves as the input for the next. This kind of design is very simple, clear, and easy for everyone in the group to understand.

In the next series, three longer, more intensive games are interspersed with two shorter games. The shorter games might give the groups a chance to loosen up a bit between more intensive activities.

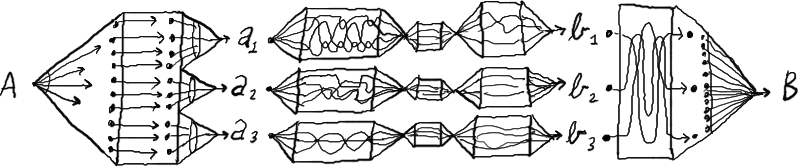

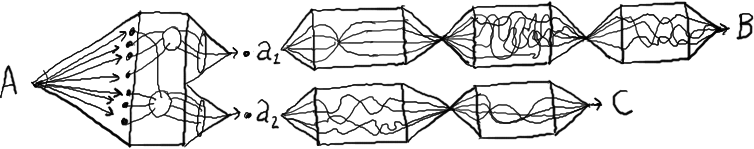

Sometimes, especially with a larger group, it makes sense to pursue multiple goals. A key concept in game design is a variation on opening and closing called break out/report back, where a larger group diverges by breaking out into smaller subgroups, plays a game or two, and converges by reporting back the outcome of their efforts to the larger group. This is a way to keep groups small and dynamic, and also increase the variety of ideas, by playing multiple games in parallel.

People also need time to reflect on ideas. Breakouts (or breaks) can be a good time for this. Break out/report back is a way to balance sharing and reflection and to create quiet time. For example, you can ask people in a group to spend time working on an individual exercise which they can then share with the group.

Here's a series where an initial, opening session reveals three different goals that can be pursued in parallel breakout groups. At the end of the series the three groups' outcomes are shared in a report-back session with the larger group.

Here's a series where the outcomes of the first game generate inputs for five games, which generate inputs for two games, which generate the input for a single, longer game. This kind of string might indicate a workshop including multiple ideas and agendas that need to be worked on in parallel.

Here's a daylong game where a big chunk of the morning is spent on divergent activities, generating a lot of ideas and information, and the exploration phase is split into two parts, with a break for lunch, followed by an afternoon of convergent activities that flow into a single outcome. The group will lunch together at four tables for informal conversation and reflection on the morning's activities before going into the afternoon session. This kind of design might be appropriate for a group where everyone had some level of interest in every component of the day, and nobody wanted to be left out of any part of the game.

Sometimes you make discoveries while a game is underway that require a change in direction. In the following series, the initial opening and exploration revealed a new goal that the team had not anticipated. The group agreed to break into two subgroups; one group pursued the original goal and the second worked on the new goal.

OK, so it's time to compose a game, or maybe a series of games. Where do you begin? What do you compose with? Remember that gamestorming is a way to approach work when you want unpredictable, surprising, or breakthrough results—a method for exploration and discovery.

Think about the people who explored the natural world for a moment: people like Columbus, Lewis and Clark, Ernest Shackleton, and Admiral Byrd. Imagine what it must have felt like to be one of these explorers. You are searching for something that you may not find. You will almost certainly find things you don't expect. You have only a vague idea of what you will encounter along the way, and yet, like a turtle, you must carry everything you need on your back.