AT THIS POINT, IF YOU FEEL READY, YOU MIGHT WANT TO FLIP to the games section of the book and read a few of the games, or maybe try a few with some friends or colleagues. If not, and you'd like to learn more about gamestorming skills, keep reading. In this chapter, we will take a closer look at some of the essentials and how they work, namely:

- Questions:

The core fire-starting skill that ignites the initial spark

- Artifacts and meaningful space:

The boards and playing pieces that form the backbone of most games

- Visual language:

The ability to make your imagination and ideas more tangible and sharable

- Improvisation:

The ability to explore experiences with your whole self; your heart and body as well as your mind

If you're ready, let's dive in.

Perhaps nothing is more important to exploration and discovery than the art of asking good questions. Questions are fire-starters: they ignite people's passions and energy; they create heat; and they illuminate things that were previously obscure.

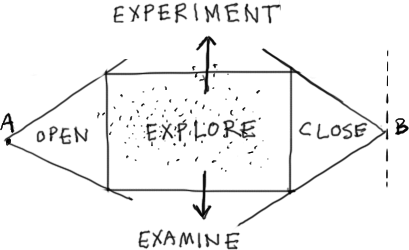

In life and in business, we are often in a position where we want to go from point A to point B. When the path from A to B is clear, we can draw a straight line and be done with it. Whether that path is easy or difficult is beside the point.

A question is one half of an equation, where the other half is usually unknown. If the question is "How do we get from here to there?" and the answer is known, the equation is fulfilled and we have our answer. We can draw a straight line from A to B. This is the process answer, where we describe the path from A to B as a series of steps.

When the path from A to B is unclear, we have a different kind of challenge. If we ask the same question, "How do we get from here to there?" we need to face the fact that we don't know the answer. The answer in fact may be not only unknown but also unknowable: not all questions are answerable.

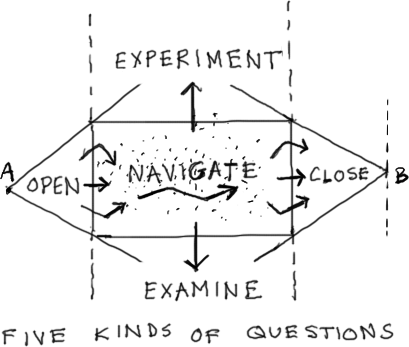

Crossing this kind of challenge space is a journey into the unknown, like crossing a desert or sailing into uncharted waters. When you begin, it's impossible to know how near or far the answer—if there is an answer—may be. There are five kinds of questions for finding your way in complex challenge spaces: opening, navigating, examining, experimental, and closing questions.

As we've seen, in any knowledge game you must open the world, explore the world, and close the world. In between points A and B you must navigate as best you can to ensure that you are making the progress you want.

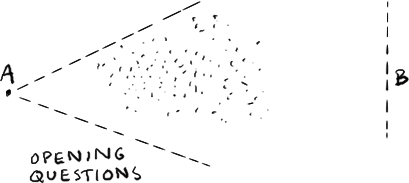

Opening questions are intended to open a portal into the game world. The opening stage of your game is the first act, where the players get to know each other and, together, you identify the main themes you want to explore in the next stage. The trick of opening is to get people to feel comfortable with the process of working together while generating as many ideas as possible. If they know each other too well, they will have trouble breaking out of the traditional limits of their collective culture and their ideas will be too similar. If they are complete strangers, they will generate a lot of diverse ideas but may have trouble working together as a team.

The idea behind an opening question is to generate ideas and options, to provoke thought and reveal possibilities, to jump-start the brain. Good opening questions open doors to new ways of looking at a challenge. The feeling you are striving for is a sense of energy and optimism, where anything is possible. A good opening is a call to adventure.

For example, you might start by brainstorming a list of questions about the challenge space. Focus on quantity, not quality. Withhold criticism and welcome unusual or controversial ideas. Look to build on ideas and combine them to make them better.

The focus of opening questions is to find things you can work with later. Imagine yourself with a big basket that can hold an infinite number of ideas. If you find something, don't ask if it's useful; just put it into the basket. The more ideas and variation you have, the better.

Here are some examples of opening questions:

"How would you define the problem we are facing?"

"What kinds of things do we want to explore?"

"What are the biggest problem areas?"

Navigating questions help you assess and adjust your course while the game is underway. For example, summarize key points and confirm that people agree to ensure that you understand and that the group is aligned.

Is the team fatigued? Are they frustrated or sapped of energy? Take a break and check in. Ask them questions that will help them see how difficult the problem is or how far they have come.

Are you getting where you need to go? Have you made as much progress as you had hoped? Are people still feeling connected to the project? Ask them!

Before you ask too many navigating questions, keep in mind that you may have more experience navigating complex challenge spaces than some of the other people in the room. You may have a better sense of how far along you are than they do. If you are the captain of the ship, it may make people nervous if you express too much doubt.

Navigating questions set the course, point the way, and adjust for error. Here are some examples of navigating questions:

"Are we on track?"

"Did I understand this correctly?"

"Is this helping us to get where we want to go?"

"Is this a useful discussion thread?"

"Should we table this for now and put it on a list of things to talk about later?"

"Does the goal that we set this morning still make sense, or should we make some adjustments based on what we have learned so far?"

There are two big questions that are worth asking whenever you come across something new. First, what is it? And second, what can I do with it? The first question has to do with examination, while the second deals with experimentation.

Examining questions invoke observation and analysis. What is it? What is its nature? The more closely you look at something the better you can examine it. Examining questions narrow your inquiry to focus on details, specifics, and observable characteristics. They make abstract ideas more concrete by quantifying and qualifying them. You can imagine an examining question as a lens that allows you to zoom in to a topic so that you can see more detail. Usually it's good to begin an exploration by examining and challenging your fundamental assumptions.

Note

If your idea were a rock, examining questions would help you understand things like its weight, color, size, shape, and chemical makeup.

Here are some examples of examining questions:

"What is it made of?"

"How does it work?"

"What are the pieces and parts?"

"Can you give me an example of that?"

"What does that look like?"

"Can you describe it in terms of a real-life scenario?"

Experimental questions invoke the imagination. They are about possibility. What can we do with it? What opportunities does it create? Experimental questions are concerned with taking you to a higher level of abstraction to find similarities with other things, to make unlikely and unexpected connections. Whatever "it" is, experiment with it. Try to break it, throw it, spin it, invert it, and so on.

If your idea were a rock, experimental questions would ask "What can I do with this that's beyond the obvious?" For example, you could use it to hammer a nail, or you could throw it, make noise with it, and so on. One day someone asked questions like this, came up with the idea for the pet rock, and made a million dollars.

Here are some examples of experimental questions:

"What else works like this?"

"If this were an animal (or a plant, machine, etc.), what kind of animal would it be, and why?"

"What are we missing?"

"What if all the barriers were removed?"

"How would we handle this if we were operating a restaurant? What if it was a hospital?"

"What if we are wrong?"

You can think of this as a matter of altitude. When people are getting too caught up in the details, spark the imagination and bring them up a level with some experimental questions. If they are up in the clouds and need a bit of grounding, bring them down with some examining questions.

Closing questions serve the opposite function from opening questions. When you are opening you want to create as much divergence and variation as possible. When you are closing you want to focus on convergence and selection. Your goal at this stage is to move toward commitment, decisions, and action. Opening is about opportunities; closing is about selecting which opportunities you want to pursue. That means eliminating lines of inquiry that don't seem promising, assigning priorities, and so on. Now is the time for critical thinking.

Closing is like coming home. You are tired but you want to end the day with a sense of accomplishment. What have you achieved? What have you accomplished? The natural need for a feeling of accomplishment is one of the reasons why tangible outcomes are so important in gamestorming. The fact that people have created something tangible—even if it's simply a report or to-do list—helps the group maintain momentum and generate energy for the next phase of activity.

People want to know: Where is the artifact? What is finished? What comes next? What will tomorrow look like?

Here are some examples of closing questions:

"How can we prioritize these options?"

"What's feasible?"

"What can we do in the next two weeks?"

"Who is going to do what?"