The world of master chess is so brutally competitive that the chess masters are quick to develop a hard-boiled attitude. This sometimes takes strange forms, as in the case of Howard Staunton, the British master and Shakespearean critic who was the leading player of the 1840s.

Staunton was pompous and bombastic, a self-appointed dictator of the chess world. On one occasion a rival published a statement that he had won the majority of his games with Staunton. The next time they met Staunton thundered, “You can’t print that!” His rival stammered feebly that the statement was true. “What’s that got to do with it? Of course it’s true!” Staunton raged. “But you still can’t print it!”

In the world of tournament chess, alibis are a dime a dozen, but the final score is all that counts. “Let’s look at the record” is more than a mere phrase as far as chess is concerned. Reputation and playing strength are all very well, but what really matters is: what does the final score table show?

The stark emphasis on results highlights the rise and fall of great names. Brilliant youngsters appear in the arena. They make a favorable impression; they improve; they reach the topmost ranks. As mature masters they are men of world-wide reputation, included in the handful of the world’s best. They taste fame and (some) fortune; they are universally admired (or envied). At the brilliant zenith of their careers they seem immortal, good enough to last forever.

Then, at first slowly, and later more rapidly, their powers gradually decline. New men begin to spring up, and one day the chess world collectively rubs its eyes to find that a former world champion has imperceptibly turned into a has-been. To the chess fans of an older generation it is nothing short of tragedy to see their idols topple. The younger generation on the other hand, admires the newer crop of masters and looks at the oldsters as a bunch of overrated duffers long past their prime.

So when we discuss this or that master, we must often specify the period of his career. If we talk about Steinitz, do we mean the brilliant youngster who became world famous because of his brilliant sacrificial play, or do we mean old Steinitz, the lawgiver of order and system, intent on maintaining the balance of position and accumulating microscopic advantages?

As for Tarrasch, do we mean the teenage youngster who neglected his homework to stare starry-eyed at the grizzled veterans who had played against the great Anderssen? Do we mean the up-and-coming young Tarrasch who won tournament after tournament to become a candidate for world championship honors?

Do we mean the mature, world famous Tarrasch presenting an appearance of superiority to the world and inwardly quaking as he feels his chess powers gradually diminishing? Or do we mean the old, venerable Tarrasch, now overtaken by a host of younger men who write admiring, respectful articles about him and trounce him mercilessly in the tournament room? So many Tarrasches – and yet they are one and the same man!

There is still another way we can asses a master’s style and the changes that age brings about. Up to the age of 20 or so the masters are daring, mettlesome, always ready for headlong risks and sacrificing “on spec.”

In the early 20s they change. They realize that more than one road leads to Rome, and they learn how it is possible to grind down an inferior opponent by the “inevitability of gradualness.” They learn, from distressing experience, that risk-taking does not go hand in hand with winning tournaments. They are taught that you can’t storm the bridges of Parnassus in every game and still win out against first-class rivals. The dullness of everyday living begins to rub off on them as they discover that glamour doesn’t always pay off.

From 25 to 35 their playing strength rises steadily. 35 is probably the great master’s zenith age. He is at his most alert and energetic, and at the same time experience has enriched and matured his playing style.

From that point on a slight falling off becomes noticeable. There is a greater tendency to fatigue, to boredom. Inspiration doesn’t come so readily. But experience, practical flair, crafty appraisal of a rival’s weakness – these are priceless assets to the aging player which keep him at or near the top. Then too, the player in the late 30s and early 40s is wise enough to preserve his strength for supreme efforts.

From 45 on there is a steady decline. There are still individual days when an old master produces a masterpiece. Emanuel Lasker won the great international tournament at New York in 1924 when he was fifty-six. Steinitz played the most beautiful game of his life when he was 59. Alekhine, despite drugs and excessive drinking, was still a dangerous opponent when he died at the age of 53. Blackburne played credibly in the St. Petersburg tournament of 1914 when he was well over 70.

Still, these are exceptions. The general rule is that chess, despite all popular prejudice to the contrary, is a young man’s game. Old age is a handicap – a crushing handicap. But just for that very reason there is a sentimental pleasure in seeing an old-timer at the very top of his form. For who of us doesn’t like to see Father Time cheated?

The dazzling game that follows is the most delightful example I know of in which old age trounces youth. When this game was played Burn was 63; Tartakover was 24. You’d never guess it from the way the game went.

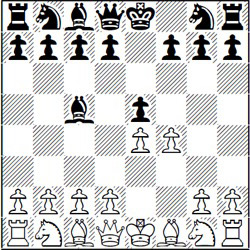

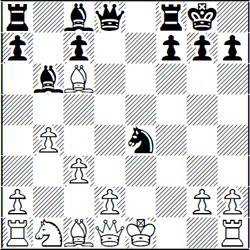

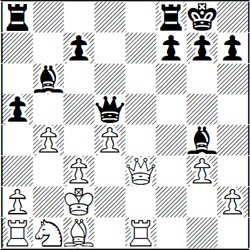

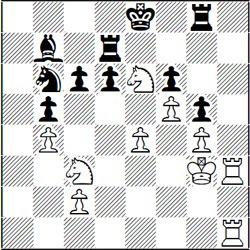

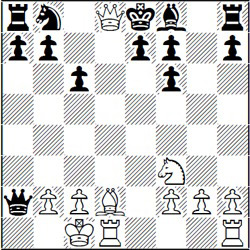

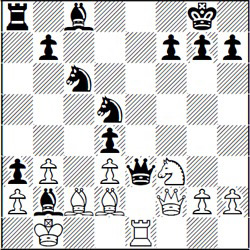

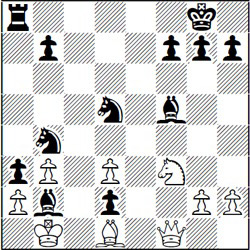

1.e4 e5 2.f4 Bc5 (D)

A standard opening trap. If White tries 3.f×e5? then 3...Qh4+ cooks his goose.

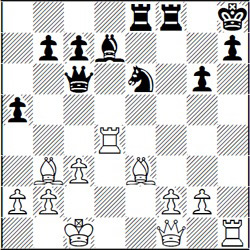

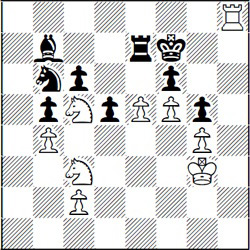

3.Nf3 d6 4.f×e5 d×e5 5.c3 Nc6 6.b4? ... (D)

This move only weakens White’s position without succeeding in driving Black’s c5-bishop off its mighty diagonal

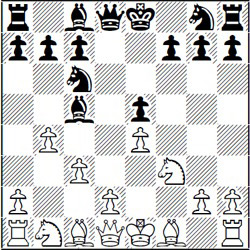

6...Bb6 7.Bb5 ... (D)

Now that White has pinned Black’s queen knight he threatens N×e5.

In his younger days Burn was an extremely careful player who would have heeded this threat, but in his old age he became more enterprising. Consequently he ignores the threat and instead concentrates on development.

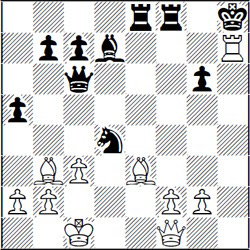

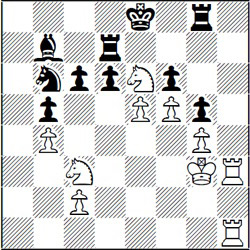

7...Nf6!! 8.N×e5? 0-0!

Still more development. He gives up another pawn, for he has a jolting surprise in store for his cocky young opponent.

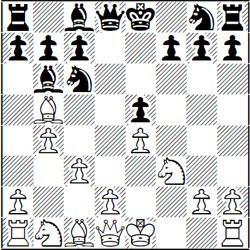

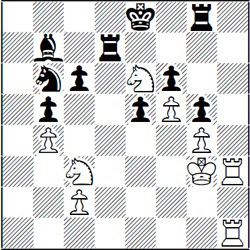

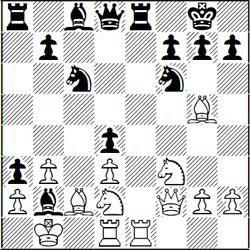

9.N×c6 b×c6 10.B×c6 ... (D)

White has picked up two pawns and expects to gain time by forcing Black’s attacked rook to move. But he gets the surprise of his young life when Burn plays:

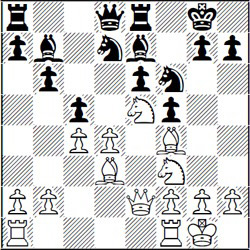

10...N×e4!! (D)

The startling sacrifice is possible because White’s king is exposed to attack and because he has lost time running after stray pawns. If now 11.B×a8 Bf2+ 12.Kf1 Ba6+ and Black wins the queen. Or 11.B×e4 Qh4+ and Black has a winning attack.

11.d4 ...

White discretely shuts out the obnoxious bishop.

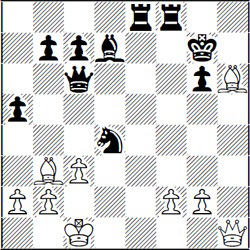

11...Qf6! (D)

Very pretty. Black threatens ...Qf2 mate and attacks White’s bishop. Thus White’s reply is forced.

12.B×e4 Qh4+ 13.Kd2 Q×e4 14.Qf3 ... (D)

If Tartakover thinks his last move forces the exchange of queens, he immediately finds that he’s mistaken.

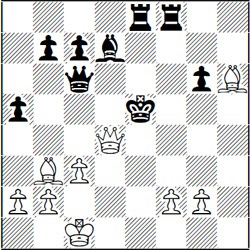

14...Qh4!! (D)

For if 15.Q×a8 Qf2+ 16.Kd3 Bf5+ and Black wins the queen.

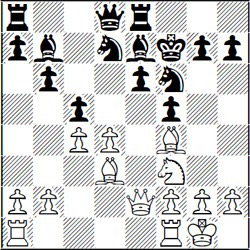

15.g3 Qg5+ 16.Qe3 Qd5 17.Re1 Bg4 18.Kc2 a5! (D)

Black continues to play with superb dash and vigor. By a series a smashing blows he opens up the white position for the final attack.

19.b×a5 R×a5 20.Ba3 c5! (D)

The crowning touch. More lines are opened up and Black is ready to break through.

21.d×c5 R×a3! (D)

Black has again sacrificed material but he soon regains it with interest as he slams the white king around.

22.N×a3 B×c5 23.Qe5 Bf5+! 24.Kb2 Qb7+! 25.Kc1 B×a3+ (D)

The slaughter continues.

26.Kd2 Rd8+ 27.Ke3 Rd3+ 28.Kf2 Qf3+ 29.Kg1 Rd2 30.Qe8+ Bf8 Resigns (D)

White is helpless against the coming mate. Burn’s dashing play in this dramatic game is notable for its sustained vigor.

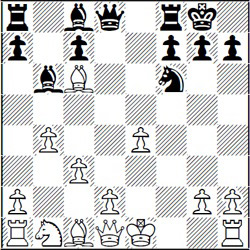

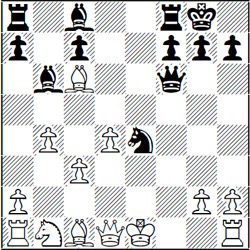

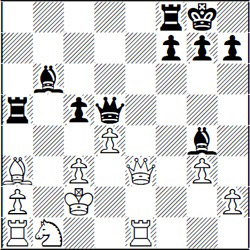

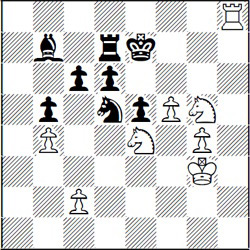

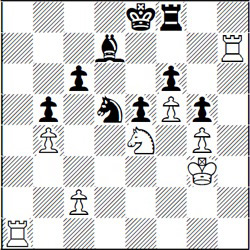

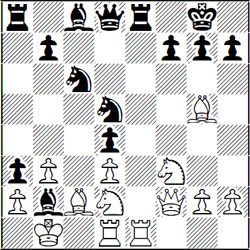

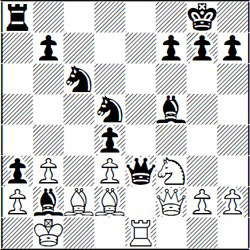

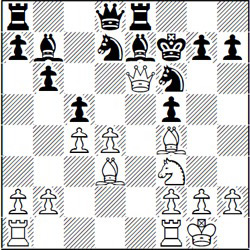

Wilhelm Steinitz, who was world champion for almost 30 years went through some remarkable changes of style. As I’ve indicated, he started as an exceptionally brilliant player and ended up as the great master of position play. However, even in his old age he often reverted to extraordinarily brilliant combinations. Here is an example from the 1892 world championship match with Chigorin, when Steinitz was 56 and in very poor health. (D)

Steinitz – Chigorin

White to move

Steinitz has a strong initiative based on his open h-file. In order to make the most of this advantage he must open up the game in the center so that his bishops can take part in the attack. Steinitz sizes up the situation impeccably and crushes his opponent before he quite realizes what it’s all about.

The gist of Steinitz’s plan is to remove Black’s knight. Once this knight goes, White’s bishop on b3 obtains a mighty diagonal that means death to the black king.

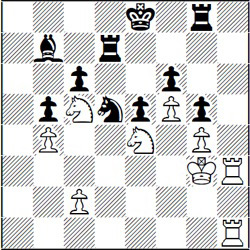

1.d4! ... (D)

Threatens to win a piece by d5. Black sees nothing better than capturing the dangerous pawn.

1...e×d4 2.N×d4 ... (D)

Now Black is in serious trouble. If he tries 2...N×d4 (opening the bishops diagonal!) White smashes through with 3.R×h7+! K×h7 4.Qh1+ and mate follows because Black cannot escape with ...Kg8.

2...B×d4 3.R×d4! ... (D)

Beautiful play. Steinitz is still trying to get rid of the knight. If Black refuses to play ...N×d4, then Steinitz wins easily and quickly with 4.Rdh4. All this is played with the majestic ease and simplicity of a great master who makes things look deceptively easy.

3...N×d4 4.R×h7+!! ... (D)

This brilliant move, for which Steinitz has been angling for some time, comes as a shattering surprise to his opponent.

4...K×h7 5.Qh1+ Kg7 6.Bh6+! (D)

If now 6...Kh8 7.B×f8+ followed by mate. Note that the whole combination hinges on the fact White’s bishop on b3 strikes along the whole diagonal, preventing such escape moves as ...Kg8 or ...Kf7.

6...Kf6 7.Qh4+ Ke5 8.Q×d4+ Resigns (D)

For after 8...Kf5 White has 9.Qf4 mate.

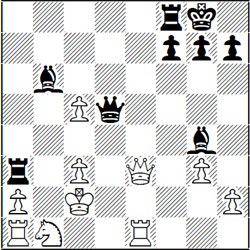

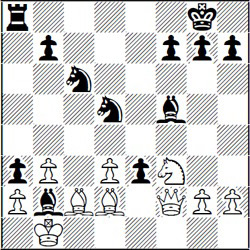

One of the most thrilling duels of old age versus youth was seen in the St. Petersburg international tournament of 1914, one of those outstanding contests which has the chess fans reminiscing for decades. In this exciting event Emanuel Lasker, then world champion and aged 46, managed to nose out his chief rival, Capablanca (then 25).

Capablanca took an early lead, winning game after game in impressive style. Lasker, who had not played for several years, took time to reach his best form, and when he finally met Capablanca in the deciding game, the Cuban still had a substantial lead. A draw was good enough to win the tournament for Capablanca, while Lasker had to win the game in order to have a chance to win the tournament.

Now Lasker was always a great “money” player. Some masters can play great when the going is smooth. But when there are difficulties, or when a game reaches the critical point, they crack. Not so Lasker. The more dangerous the situation, the more determined he became. He had iron nerves and ice-water veins.

Lasker’s specialty was to prove to his opponent that simple things are not so simple after all. He knew how to create drama out of dullness, how to make something out of nothing. This made him a terribly dangerous opponent, because you never knew when you were really safe. Even while you were breathing a sigh of relief at having escaped the worst, he was busily weaving an indestructible net out of the most unlikely materials.

It was precisely this method Lasker used in his vital game with Capablanca. Exchanging queens early in the opening Lasker gave the impression that he was not intent on fighting after all. And yet little by little difficulties appeared: trifles, and yet puzzling. Capablanca vacillated between confidence and worry. It was all too simple; he couldn’t believe it.

Little by little Lasker created small-scale crises, confronted Capablanca with unwelcome choices and disagreeable decisions. Soon Capablanca began to lose the thread of the game. One crafty Lasker move after another reduced him to a state of helplessness. At last Lasker reached the stage of applying slow torture as described in Chapter Two. Capablanca’s position became so constricted that successful resistance was no longer possible.

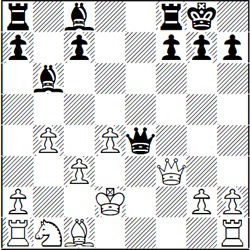

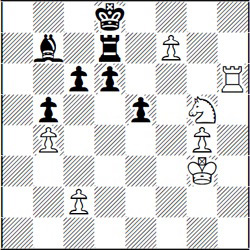

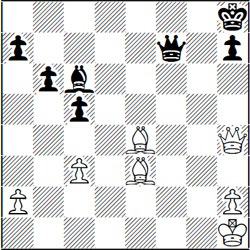

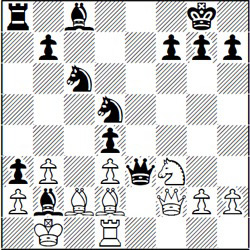

The question was: how would Lasker finally decide the game in his favor? (D)

This was the position in which Lasker closed in for the kill.

1.e5!! ... (D)

A remarkable move. Black has two ways of capturing the pawn free of charge, and he can decline it. What then is the purpose of the astonishing pawn move? Its object is to create new squares for White’s knights to move to. Once established on these new squares, the knights become so menacing that Black can no longer hold the position. Thus, if Black plays 1...f×e5 there follows 2.Ne4 Nd5 3.Rh8! R×h8 4.R×h8+ Ke7 5.N6×g5. (D)

Analysis after 5.N6xg5 (D)

Now Black has nothing better than 5...Nf6 and after 6.N×f6 K×f6 7.Rh6+! Ke7 (7...K×g5 8.Rg6 mate) 8.f6+ Kd8 9.f7 the far advanced passed pawn assures White an easy win. (D)

Analysis after 9.f7

Returning to the position after 1.e5, Black can also refuse the pawn. But he’ll still come to a bad end, thus: 1...d5 2.Nc5!! Re7 3.Rh8! R×h8 4.R×h8+ Kf7 (D)

Analysis after 4...Kf7

5.Rh7+ Ke8 6.R×e7+ K×e7 7.e×f6+ K×f6 8.N×b7 winning a piece.

(These variations aren’t easy to understand at first glance. Remember they represent the superb achievement of a world champion at one of the crucial moments of his lifetime. They are, however, unusually instructive, and you will find them well worth playing over several times. This will clarify them in your mind and bring out many hidden beauties of the moves.)

Realizing that 1...f×e5 or 1...d5 won’t do, Capablanca tries a different way.

1...d×e5 (D)

But this is no better than the other tries. Lasker’s knights become fearfully agile, and his rooks penetrate into the heart of Black’s position.

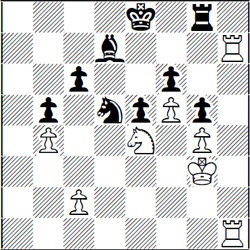

2.Ne4 Nd5 3.N6c5 ... (D)

This wins the Exchange, for if Black’s rook runs away the damage is even greater, for example, 3...Re7 4.N×b7 R×b7 5.Nd6+ winning a whole rook.

3...Bc8 4.N×d7 B×d7 5.Rh7! ... (D)

After 5.Rh7

The classic position of the rook on the “absolute” seventh rank. Black is paralyzed. Black can’t hold out much longer.

5...Rf8 6.Ra1! ... (D)

After 6.Ra1!

And now the other rook penetrates. White threatens checkmate.

6...Kd8 7.Ra8+ Bc8 8.Nc5 Resigns (D)

White has three checkmating threats beginning with 9.Rd7+ or 9.Ne6+ or 9.Nb7+. Black must give up.

This was Lasker’s description of the scene: “The spectators had followed the final moves breathlessly. That Black’s position was in ruins was obvious to the veriest tyro. And now Capablanca turned over his king. From the several hundred spectators there came such applause as I have never experienced in all my life as a chessplayer. It was like the wholly spontaneous applause which thunders forth in the theater, of which the individual is almost unconscious.”

To the amateur, blindfold chess seems miraculous. And he’s quite right. Many a noted blindfold player has a perfectly matter-of-fact explanation of his skill in this department. And yet the fact remains that prosaic explanations can never strip the glamour from blindfold chess.

Our modern blindfold experts have reached the point where they can conduct 45 games blindfold simultaneously. That remains one of the greatest feats of the human mind, no matter how calmly it’s explained or deprecated.

Once when I was asked to list the qualities needed for playing blindfold chess, I really had to think hard about this amazing skill. It seemed to me, after a great deal of reflection that four qualities are needed.

The first of these qualities is obvious: a prodigious memory. Some of the masters have fantastic memories. It was said of Boris Kostich, the Yugoslav master, that he could remember every game he had ever played over. And Frank Marshall, after giving a monster simultaneous exhibition on 155 boards, was able to recall all but two of the games several days later. At that he tsk-tsked over his forgetfulness!

Another vital quality is pictorial imagination, which gives the master a clear picture of the position on each board; and powerful concentration. Obviously, if you’re going to day-dream while you’re playing chess, you’re not cut out to be a blindfold player.

Finally, a blindfold player needs the ability to glide from one subject to another without forgetting the first image. That’s a difficult quality to perfect; just try to remember everything you see in a hardware store window and you’ll realize the difficulty!

Harry Nelson Pillsbury, the great American master who died at the age of 34, was a phenomenal blindfold player. He once gave a blindfold exhibition on 21 boards against players of master strength and did very well! But even this feat seems easy in comparison to his specialty of playing 12 games of chess, six games of checkers, and a hand of duplicate whist – all at the same time!

A spectator said of Pillsbury that “while conducting the card game with all the precision of a fairly good player, he would keep the ever-changing chess and checker positions at his back clearly in his mind’s eye, and call off his moves at each board with an accuracy and promptness that looked little short of miraculous. He could break off a séance for an intermission and upon resumption when requested, would announce the moves in any particular game from the beginning.”

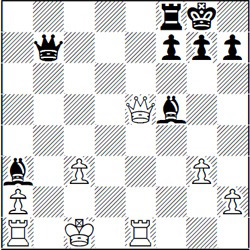

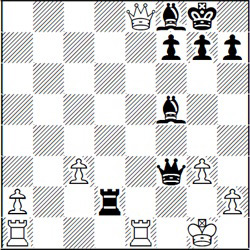

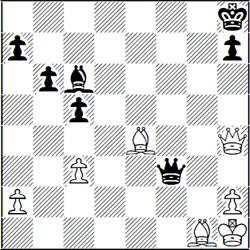

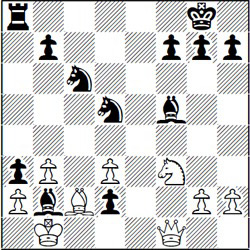

Well, all this is very fine, you may say, but what did he do? Here’s a sample of Pillsbury’s genius at blindfold play. (D)

Amateur – Pillsbury

Black to move

Though Pillsbury is behind in material, he has a glorious winning line which doesn’t escape his “eagle eye”:

1...Qf1+!

An important preliminary to the coming sacrifice. The white king must be wedged tightly into the corner.

2.Bg1 Qf3+!! (D)

Beautiful!

3.B×f3 B×f3 mate! (D)

What a man! And what imagination!

George Koltanowski, who has done much to popularize chess in this country on his innumerable tours, is one of our best modern blindfold players. He’s often content to play straight positional chess or lead into the endgame, which, in the course of a long blindfold session, is not as easy as it sounds.

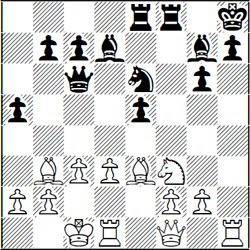

However, Koltanowski can also be brilliant when the occasion warrants, as in the following position: (D)

Black threatens mate on the move (...Qa1 mate.) Most players would be thinking of how to meet this threat. So does Koltanowski – but what a move he finds!

1.Qd8+!! ... (D)

Don’t forget White is playing blindfold!

1...K×d8 2.Ba5+ Kc8[e8] 3.Rd8 mate!

But the blindfold player I admire most of all is Alekhine. In one of his books he revealed that while still a child he was taken to see Pillsbury play blindfold, and the exhibition made an unforgettable impression on him. Given Alekhine’s marvelous powers of imagination and concentration, it was no wonder that he developed such uncanny powers as a blindfold player.

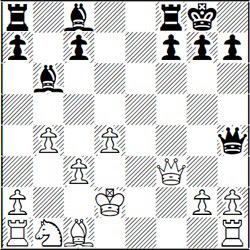

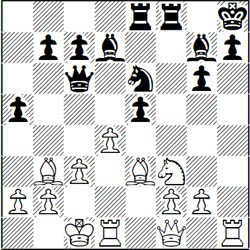

Among Alekhine’s numerous blindfold gems there are two that stand out. Here’s one of them: (D)

Amateur – Alekhine

Black to move

Black’s king knight is pinned. If he moves the knight he loses his queen. Nevertheless, Alekhine plays:

1...Nd5!! (D)

A droll touch. It looks like a blunder; still if White plays 2.B×d8 Black replies 2...Nc3 mate! And the best is yet to come.

2.R×e8+ Q×e8 3.Ne4 ...

Defending against the mate threat.

3...Q×e4! (D)

A sinister “echo”: if now 4.d×e4 then Black has 4...Nc3 mate. So White must scurry back to stop the mate.

4.Bd2 ...

Now Black can win pretty much as he pleases by retreating his queen, still remaining a piece ahead. Instead the “echo” persists.

4...Qe3! (D)

For if 5.B×e3 Nc3 mate. But White wants to have some fun too.

5.Re1 ... (D)

Maybe the blindfold player will stumble into 5...Q×f2?? allowing 6.Re8 mate! But Alekhine “sees” through this flimsy hope.

5...Bf5! (D)

6.R×e3 d×e3 (D)

And once more, if 7.B×e3 Nc3 mate. So White discretely withdraws.

7.Qf1 e×d2 (D)

Threatens ...Nc3 mate.

8.Bd1 ...

Providing the king with a flight square at c2.

8...Ncb4! (D)

Closing the escape hatch. If 9.any there comes 9...Nc3 mate!

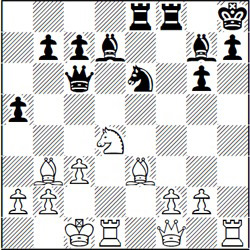

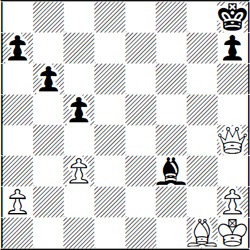

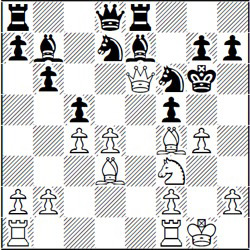

But my favorite among all of Alekhine’s blindfold masterpieces is this one, which he played in a military hospital as a wounded prisoner in World War I: (D)

Alekhine – Amateur

White to move

White’s position is overwhelming, and he can win in a hundred different ways. But only Alekhine could win in this way:

1.Nf7!! K×f7

Naturally Black takes. He has nothing better anyway, and you have to remember that the blindfold players enjoys one considerable advantage. Blindfold play is such a mystery to the amateur that when the master plays a deep combination it has all the earmarks of a colossal blunder.

Actually Alekhine’s previous move was not a blunder at all, but rather the beginning of one of the deepest combinations ever played on the chessboard. Black can hardly be blamed for having no inkling of White’s intentions. (D)

2.Q×e6+!! ... (D)

This stunning move is beyond all praise. The exquisite point is that if 2...K×e6 3.Ng5 mate! Nor does 2...Kf8 help, for then 3.Ng5 decides in White’s favor. So Black tries a different way.

2...Kg6 3.g4! ... (D)

Not a sacrifice, yet a striking move. Both Black’s f6-knight and f-pawn are pinned and meanwhile White threatens either B×f5 mate or Nh4 mate. Black resigned as he can parry one of these threats – but not both.

In this book we’ve seen what makes the masters great; we’ve also seen that, like the rest of us, they can make mistakes. The vivid imagination and assured technique of the masters fill us with awe. And yet they’re not wholly unapproachable, and there is much that the ordinary player can learn from them. How can you play with the skill of a master? There you have the theme of the final chapter.