“HOW MUCH have we got?”

The girl counted the change again, although they both knew. “Forty-one cents. That must be enough for something.”

“I don’t know. We can probably buy Life Savers or something.”

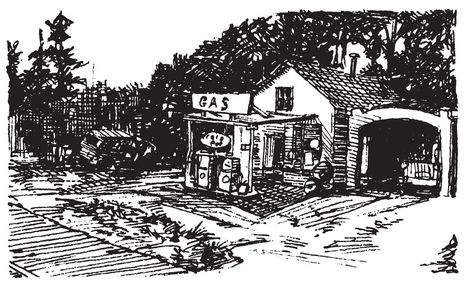

They both looked across the road at the gas station. It was old, with wooden siding that had settled into wavy lines. Someone had hung a large metal sign over the pumps. It said COLD POP.

Two bright-yellow school buses were parked on the highway shoulder. Kids were lined up at the restrooms stuck out in the pines to one side of the station. A few were dancing around the pumps, the headphones

of transistor radios clamped over their ears. Most of the kids were black. A white man in Bermuda shorts with a clipboard was leaning through the open door of one of the buses, talking to someone they couldn’t see.

“Shall we wait until they go?”

“No. I don’t know why we should. Maybe it’s better this way. No one will notice us in the crowd.”

The inside of the station was crowded with more kids. Some of them were feeding quarters and dimes into a candy machine. They were watching bags of chips and cookies spiraling out on metal coils behind the glass front. A man in greasy overalls and a cap that said Corn King was watching them unhappily.

“You! Cut that out,” he said to a tall black teenager who was slapping the machine with his hand.

“This mother just ate my quarter.”

“I’ll give you another. Just don’t hit the machine.”

The boy tried to work his way through the crowd. People bumped him, not seeing him. He felt invisible. He couldn’t find the beginning of the line where he could wait his turn to use the machine. There didn’t seem to be one. Someone gave him a nudge, and he was about to nudge back when the girl caught his hand and pulled him toward the door.

“Hey. What’s wrong? I didn’t get anything yet.”

She jerked her head toward the window. Through the dusty glass he could see that a police car had pulled into the station. Behind it was the gray Toyota Land Cruiser that belonged to the camp. As he and

the girl watched, Margo Cutter got out of the Toyota and went up to the police car. She leaned over so she could talk to the policeman inside.

“Come on. We have to get out of here,” said the boy.

“Where?”

“We’ll get into the woods out back. Let’s go before everybody leaves.”

They slipped through the door, trying to keep the other kids between them and Margo. It wasn’t too hard. Most of the kids were bigger than they were. The man with the clipboard blew his whistle, and slowly the crowd began to meander toward the buses.

Margo had turned around and was looking in their direction. She was squinting into the sun, and put her hand up to shade her eyes.

They kept their heads down, hoping they wouldn’t be noticed. The boy took the girl’s hand and tried to sidle into the shelter of the trees. The man with the clipboard grabbed his shoulder.

“Come on. Get on the bus and quit horsing around.”

The boy ducked his head and pushed the girl up the steps into the bus.

“Sit here,” he said, pulling her into the seat behind the driver. He wanted to be near the door in case they had to make a break for it.

Margo had left the police car and begun to walk toward the bus. He had a terrible feeling that they

were trapped. He craned his head around, but the back of the bus seemed crammed with suitcases and luggage. They weren’t supposed to do that. They weren’t supposed to block the emergency exit.

“Hey! What you doing in our seats?” A tall, heavy, black girl was frowning down on them. A fringe of blue-and-pink beads woven into her hair hung down over her eyes. She looked fierce and very angry.

Before the boy could answer, the teenager who had lost his quarter in the machine took the black girl’s elbow and steered her into the seat behind them. “Sit down, Tiwanda,” he said.

“What you doing? That’s Tyrone’s seat. I want my seat.” They sat down, whispering furiously.

The bus seemed full now. A white man with a gray face was moving down the aisle, counting with his hands, not letting anyone catch his eye. Through the windshield the boy could see Margo. She was standing in the middle of the drive talking to the garage-man. The policeman had gotten out of his police car and was walking toward them. He was wearing black aviator glasses. As he walked he lifted his gray straw trooper’s hat and smoothed back his hair.

“Forty-two,” said the bus driver out loud, coming back to the front of the bus. He put his hands on his hips and frowned down the aisle.

The man with the clipboard climbed the steps up into the bus so that he filled the doorway. “What’s holding things up, Wayne?”

“Nothing, I guess. I’ve got two too many.”

“Crap. Are any of you supposed to be on the other bus?” the man with the clipboard yelled.

“That’s me, man,” said someone behind them. “I’m supposed to be on the other bus.”

“No, he ain’t, Mr. Carlson. That’s me. I’m supposed to be on the other bus with Lydia.”

“What you talking about Lydia?” someone demanded. The boy could feel the bus shake as people started standing up.

“Everybody sit down!” said the man with the clipboard. “We’ve got them all, Wayne. Let’s get going.”

The bus driver waited until the man called Carlson backed down the steps, and then he cranked the door closed and started the bus. As they pulled past the gas station, the boy could see the top of Margo’s head. She was shaking it. In anger, frustration; he couldn’t tell.

The bus picked up speed. Dark pine forests stretched off invitingly on either side. A few feet from the road they were so dark that he couldn’t see into them. The girl picked at his shirt.

“Where are we going?” she mouthed at him silently.

He shrugged and tried to smile at her. She made a face of mock terror and rolled against him.

Someone was pulling at the back of their seat, and he looked up. A thin smiling black face was leaning over them.

“Hey. How’s my man?”

“Okay.”

The black teenager smiled and nodded as if that were the right answer.

“That your chick?” he asked, tipping his head at the girl.

“Yes,” said the boy.

“Nice.”

“Hey, Calvin, you leave them alone,” the girl named Tiwanda said from behind the seat. Calvin looked startled and disappeared abruptly.

“Hey, man, what you do that for? I was just saying how do you do.”

“Leave them alone, you hear?”

The black girl stuck her head over the seat. She had small delicate ears with gold earrings.

“Here,” she said, pushing a can of Coke into the girl’s hands.

“Thanks,” said the girl.

“That’s okay. It’s warm.” Tiwanda waited until the girl had opened the can and taken a sip. Then she sat back, looking satisfied.

The boy and girl took turns drinking out of the can. It was the first time she had ever shared a glass or a can with someone other than her mother, actually putting her mouth on the same place. It meant that she was getting his germs. She was getting his germs; he was getting hers. She didn’t mind. If they had the same germs, she reasoned, they would be all right.

It was warm on the bus. The air smelled of hot plastic and the sweet rich smell of the stuff that some

of the black kids put on their hair. He felt very tired. He wasn’t hungry anymore. Just tired.

The girl was drifting into sleep beside him, leaning against his shoulder. He turned his head carefully and smelled her hair. He could smell the lake and something spicy and private underneath.

“What are you doing?” she said.

“Smelling you.”

“Boy, you’re gross,” she said comfortably, not taking her head away.

When she was asleep he let his head loll back against the seat so that he could look out the side window. The bus flashed over a bridge and he caught a glimpse of a stream rushing down a hillside over dark rocks and black fallen trees. He thought he saw something moving there. A deer, maybe, with heavy branching horns, running in the same direction the bus was going. He would have sat up, but he was tired, and he didn’t want to disturb the girl’s head on his shoulder. It was too late to see anything, anyway. Perhaps he would see the deer later.

He began to think again of what it would be like for them to live alone somewhere in the woods. Like deer. People didn’t see deer very often, unless they came down out of the woods. They would need supplies. Blankets and things. An ax or something to cut wood. He remembered the cottage where he had broken in. There were other cottages. They could probably find in them everything that they needed. They would keep track of what they took, of course.

Perhaps they could even leave a note with their names. People would know they were out there, somewhere in the woods, but they wouldn’t be able to find them. They could build a shelter in some hidden place: a cave, a tangle of trees knocked over by storms. Or maybe it would be best to keep moving, building small, smokeless fires at night. He was good at that sort of thing. At Indian lore. It was about the only thing he had liked at camp. It wouldn’t be so hard. Not as hard as going back to camp. Winter, of course, would be more difficult. He could see the girl, dressed in clothes the color of fallen leaves, the smile at the corners of her mouth. He drifted into sleep, his imagination absorbed in dreams of them surviving alone.

He woke up when the bus turned off the highway onto a gravel road. The headlights swept over a weedy verge coated with dust and a sign that said Camp something or other. It was gone before he was able to read it. The girl was still asleep, leaning heavily against his shoulder.

They had drawn quite close to the other bus. Its square yellow back and glowing taillights filled the windshield. Some kids were smiling and making gestures out the window in the rear emergency door. He couldn’t understand what they were trying to tell him. It couldn’t be important, he decided.

The buses followed the road a long way, descending into narrow ravines filled with mist and climbing out again in low gear. They made a number of turnings

and occasionally would cross another minor road. At first the boy tried to keep track, but after a while he gave up. It was going to be hard to find their way back to the highway. Perhaps they wouldn’t be able to. He wasn’t sure that it mattered.

The bus finally stopped in front of a long low building. Over the double screen door was a single light bulb, around which pale, fragile insects were swarming.

The bus driver turned off the engine and began flipping switches. The bus was filled with harsh light. The girl sat up and stretched, and then hunched over, shivering slightly.

“Where are we?” she whispered.

“I don’t know. It’s a camp of some sort. We’ll get off when the other kids do and then just walk away. It’s dark. Nobody will notice.”

She nodded and leaned forward, trying to see out into the dark through the reflection in the windshield of kids crowding the aisles.

The bus driver had cranked open the door, and the smell of pines welled up the steps.

“Everybody stay in your seats … Stay in your seats!” he repeated in a loud voice. “Mr. Carlson will tell you when you can get off. We don’t want people wandering around and getting lost.”

“Hey, man. How long?” someone asked. “I’m about to piss myself.”

The bus driver looked as if he might say something,

but then he got off the bus, fumbling in his jacket for his cigarettes. The boy and girl sat still, listening to the kids talking and laughing behind them.

After a few minutes the man with the clipboard bounded up the steps.

“Okay, ladies and gentlemen, in a minute we’re going to get off the bus.” The kids whistled and cheered, and he waited until they had quieted down. “Be sure to bring all of your personal belongings. We’re going to lock up the buses for the night, and what you don’t have you’ll do without. Is that clear? Okay, then. This building you see out here is Camp One. That’s the dining hall. That’s where we’ll eat and play games …” He paused, turning red and smiling, for another cheer. “Mrs. Higgins is at the south end of the building. That means you turn left when you get off the bus. I’ll be at the other. Girls rendezvous with Mrs. Higgins. Boys with me. We’ll show you where your cabins are. Cabin assignments are final. No switching around. Okay? Everybody knows their left hand from their right? Okay. Don’t forget any of your stuff.” He nodded and backed his way down the steps.

The boy and girl worked their way into the line getting off the bus. A fat kid with a pink suitcase squeezed between them, and for a moment he was afraid they were going to be separated, but she waited for him just outside the door.

“Where do we go?” she whispered.

Kids from the bus jostled by them, claiming friends, making plans. He stood still, momentarily confused by the dark.

A tall black girl whirled against them, her eyes shining with excitement. She gathered them both under her thin, elegant arms as if she must hold on to something or fall down.

“Oh, man, did you ever see anything like that?”

She was smiling and looking up at the sky. The Milky Way was spilling coolly through the clean air. “Did you know there were so many stars? I never saw them before. Did you know there were so many?

“I don’t believe it. I just don’t believe it!” The black girl held up her hands, as if to let the glittering lights run through her fingers. She didn’t notice as the boy caught the girl’s hand and slipped away from the crowd around the bus.

They walked together straight toward the dark woods. It wasn’t far. Just beyond a small shed smelling of toilets and disinfectant, he could see the net of shadows beneath the first trees. If they could get that far, they would be safe. He could already feel the cool breath of the night woods against his face. He no longer heard the campers milling behind them. It was a shock when strong hands caught his arms from behind.

“Hey, man,” someone hissed in his ear. “What you doing? Did you think you could just walk?”

The camp parking lot was empty. Maddy stopped her car beneath a sign that said FOR OUR VISITORS and turned off the engine. As it cooled it made irregular clicking noises.

Above her, on a hill covered with dark trees, she could see the roofs of the camp buildings. It would be dark soon. Laura must be there by now, waiting.

Maddy wondered if she should have come. In her first panic upon hearing that Laura was missing, it had seemed the obvious thing to do. Now she wasn’t so sure. What if Laura should greet her with that dull puzzled look that came down over her face like a mask, making her fears into something pointless, even ridiculous? Maddy didn’t think she could stand that.

Wells had suggested that it might be better to wait. That the long drive might be for nothing. He hadn’t been so smooth and bland before he had understood that Maddy had spoken to Laura. He had been a frightened man then, almost incoherent, mumbling about the possibility of a swimming accident, trying to reassure her before she had even understood what he was talking about.

There had been a moment, no more than a few seconds really, when Maddy had thought that Laura had drowned. For those few seconds Maddy felt as if a razor had sliced deeply into her flesh, and she had stared numbly into the wound.

The misunderstanding had been cleared up quickly. The wound had closed even before she had felt the

pain. What would it have been like if Wells had called first? She hadn’t the courage to imagine.

Maddy sighed and, getting out of the car, climbed the long path toward the administration building. There seemed to be no one around. A pair of campers in white shirts that seemed to glow in the fading light eyed her suspiciously from a distance, and then glided off among the trees. There was no one else.

Inside the administration building was a long counter of yellow wood. From behind the counter a middle-aged woman looked up at Maddy inquiringly. She was deeply tanned, and her thin hair was pulled back from her forehead by the weight of a silver-and-turquoise clasp. Her small mouth was wreathed with sharp little lines.

“I’m Mrs. Golden. Laura’s mother. I want to see Mr. Wells?”

“Oh yes. Mr. Bob was waiting for you, but he just stepped out.” The woman didn’t know what to do with the papers in her hands. She considered putting them on the counter, but then changed her mind and put them on the desk behind her. “I think he’s gone to the dining hall. I’ll just fetch him.” She seemed afraid of being left alone in the office with Maddy.

“Wait a minute. Can you tell me if Laura’s come back?”

The woman stopped abruptly. “Oh, I don’t think so. Mr. Bob would know about that.” She smiled. A small, tight, give-nothing-away smile. She looked at

Maddy as if waiting for permission to go. “I’ll just fetch him. All right?”

Maddy waited. There was nowhere to sit down. On the wall behind the counter was an elaborate trophy made of lacrosse sticks and canoe paddles. It was covered with dust and varnish.

A fat man came up the steps into the office wiping his mouth. “Just grabbing a quick bite,” he said. He was wearing a Hawaiian shirt, and half-frame reading glasses dangled from a chain on his chest. “Mrs. Golden? I’m Bob Wells.” They shook hands. “And this is Miss Haskell.” He waved at the woman who had bustled back into the office behind him, nodding and smiling as if it was to see her that Maddy had driven up from the city.

“She’s camp secretary. Some of the campers seem to think she’s their mother.” Mr. Wells and the woman beamed at one another.

“Well! Come into my office, and we’ll see if we can get this business straightened out.” He led the way behind the counter and through a doorway into a small room decorated with more trophies. It seemed important to the secretary that she go in front of Maddy.

“Miss … Haskell, is it? She said she didn’t think Laura was back,” Maddy called after Mr. Wells as she picked through an obstacle course of furniture. She had an irrational idea that he might escape from her. Disappear through some hidden door.

Mr. Wells didn’t answer at once.

“Sit down, please, make yourself comfortable.” He himself sat down behind a desk and put on his glasses. He laid his hands palms down on a clean, fresh blotter.

“No. She’s not back yet.” He looked at Maddy reproachfully over his glasses.

“But I don’t understand,” said Maddy, beginning to feel frightened. “It’s hours since I spoke to her. Where can she be? I mean, what can have happened?”

“Now, now, now,” said Mr. Wells sharply. “I don’t think we should be too worried yet. We know they were safe when you talked to her. That’s the important thing. We don’t know where she was calling from, or even where they came ashore. It might take them some time to get back to camp. I really expect them any time now, Mrs. Golden.”

“But she’s only thirteen. Isn’t anyone looking for her? Something terrible …”

“Mrs. Golden, I notified the sheriff and the ranger just as soon as we knew they were missing this morning. Some of our senior counselors are out searching for them right now.” He managed to look understanding and affronted at the same time.

“But why haven’t they found her? I really don’t understand this.”

Mr. Wells looked vaguely surprised, as if she had disappointed him in some way.

“Well,” he said patiently, “we have to consider the

possibility that they might not mind making us worry a bit.” He exchanged a fruity, knowing smile with Miss Haskell.

Maddy began to feel annoyed. “Listen. Laura isn’t like that. When she says she’ll be back at a certain time, she is. I left her in your care. I want my daughter back. I want her now.”

“Mrs. Golden, no one is more aware of their responsibilities than I am. We are doing all that can be done to find them. I assure you that I am as concerned for their welfare as you are. Now”—he leaned forward, hunching his shoulders to show that he was getting down to business—“did Laura actually tell you that she was coming directly back to camp?”

“No, not in so many words …”

“I think you told her that you would meet her on Saturday at the Parents’ Weekend.”

Maddy looked at Miss Haskell. The woman nodded slightly, as if to encourage a dull student.

Maddy looked back at Wells. “Are you suggesting that she might not come back until Saturday? That’s simply ludicrous.”

“Mrs. Golden, I think I can say that I know these kids pretty well. They don’t always understand how their behavior can upset others. Particularly their parents. Now, I’m sure that Laura is as good a girl as you think she is. Believe me, Mrs. Golden, it isn’t yet time to be deeply worried.”

“Laura is …” Maddy began, and then stopped. She didn’t know what she had been going to say. In

some way the man had put her on the defensive. As if it were Laura’s behavior which had to be justified. She took a deep breath and began again. “What exactly happened, Mr. Wells? I think you owe me some kind of explanation.”

For the first time the fat man looked uncomfortable. “Not something that any of us approve of, Mrs. Golden. It was, frankly, a practical joke that didn’t work out the way it should have. Completely unsanctioned by the camp and its staff.”

“Joke? I know, you said that on the telephone. But what was the joke?”

“Well, it’s an old tradition at the camp. It started a long time back. Back when, well, frankly, there wasn’t the same attention to camper supervision that we find advisable now.” He looked at Maddy to make sure that she understood that this was an important point.

She waited. The man stirred uncomfortably. Miss Haskell cleared her throat, and Wells darted the woman a glance of such ill-concealed irritation that Maddy was taken aback. She knew very little, she realized, about these people with whom she had left Laura.

“You must know, Mrs. Golden,” he began again, “that at a large camp like this, with children from all sorts of homes, broken homes … all kinds. I’m sure you know that there are always a few campers who don’t fit in right away. That doesn’t mean that they’re unpopular. Far from it.” he said hastily, misinterpreting

Maddy’s stricken look. “These are often children who are deeply admired. The other children want to make friends with them. Make them a part of the community.”

“What did they do to her?”

“Sometimes,” Wells continued as if he hadn’t heard the pain in her voice, “sometimes there are boys and girls who are a bit, well, judgmental about their fellows. And some of the other campers might decide, mistakenly, that things could be improved if a boy and girl were put in a situation where they might realize that we are all just people. That there’s nothing wrong, for example, in a healthy interest in members of the opposite sex.” Mr. Wells smirked slightly.

“Mr. Wells, I don’t understand what you’re talking about. What did they do to Laura?”

The man surrendered reluctantly. “Well, they marooned Laura and this boy, Howie Mitchell, out on this little island together. It was to be just for the night. Not very clever, I agree.” He raised his hand before Maddy could speak. “I don’t think any real harm was meant. It’s happened before, back in the bad old days, and I don’t think any offense was taken, usually. I think most kids teased in this way would come back, well, a little proud of themselves, actually. There’s an old tent platform there. It’s perfectly safe. It’s just the other campers’ way of saying, ‘Hey, kids, come on! Get with it!’”

Maddy felt her heart constrict into a small, painful lump. “That,” she said, “is the most beastly thing I have ever heard of.”

Mr. Wells looked at her, full of compassion. “Mrs. Golden, I fully understand how this must seem to you. And I admit that for more sensitive children it might not be a good idea. And of course there’s always the possibility of an accident. Swimming accident, or something like that. That’s why I put a stop to this business as soon as I became director. We haven’t had an incident like this in years, believe me. But traditions die hard. Some of the campers here are third generation, if you’d believe it.”

“I was a goat,” announced Miss Haskell.

“What?” said Maddy. She thought the woman had said she was a goat.

“A goat. We call the island Goat Island.” She blushed. Maddy understood.

“I’m going to sue you,” she said levelly. “I’m going to sue you and this camp right into the ground.”

Mr. Wells turned bright red, and his sympathetic expression hardened by a minute degree into something made of wood. “I don’t think that attitude is going to help us, Mrs. Golden. The important thing right now is that we get Laura and Howie back, safe and sound.”

Maddy looked at him silently over his desk. It seemed strange to her that she had not realized at once that this man was her enemy.

“Now, about the boy.” Wells began to fuss with some papers on his desk, as if the boy were some last, minor detail. “I don’t think you have anything to worry about from that direction. He’s a nice boy. Quiet, wouldn’t you say, Miss Haskell?”

Miss Haskell agreed. Howie was very quiet.

“No, you don’t have to worry about that, Mrs. Golden. Howie wouldn’t harm your daughter.” He smiled as if it were, really, only a joke. “He’s about two inches shorter than she is, for one thing. You know girls at that age mature more quickly.”

Maddy hadn’t worried about the boy hurting Laura. She had never even thought of such a thing. In all her imaginings of what might happen, this had eluded her. She looked alertly from the man to the woman, wondering what other horrors might be concealed.

She heard Wells explain that they were trying to notify the boy’s parents. She understood that there was some difficulty about getting in touch with them. They were in Turkey. Digging, excavating. She wondered vaguely if they were some kind of engineer.

Wells and Miss Haskell were standing now, so Maddy got up. There was nothing more she could learn there. They would be in touch, of course. Miss Haskell explained about the reservation she had made at a local motel. She was sure that Maddy would be comfortable.

“Perhaps Mrs. Golden would like to eat with us

in the dining hall tonight. What’s the menu, Hilda?”

Miss Haskell looked doubtful. “Corned-beef hash, I think.”

“Ah! Cat’s vomit. That’s what the campers call it. Cat’s vomit.” Mr. Wells smiled at Maddy. She was afraid he might wink at her.