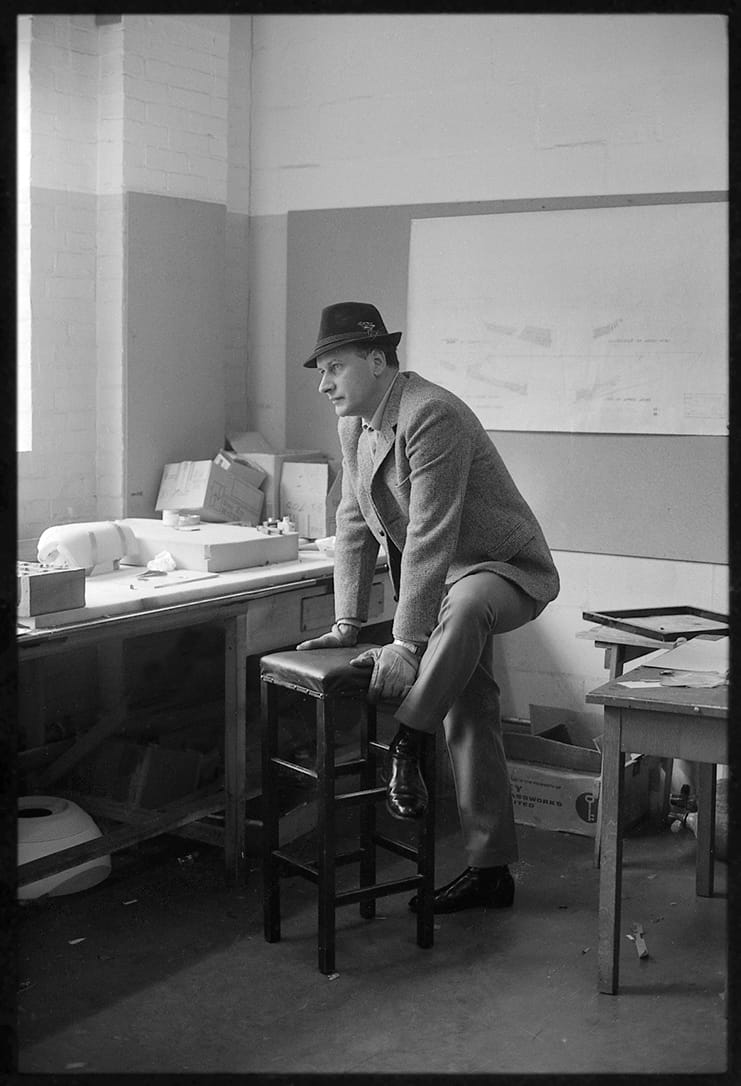

Tony Frewin. Photograph by Stanley Kubrick.

SUMMER–WINTER 1965

Perhaps our role on this planet is not to worship God, but to create Him.

—ARTHUR C. CLARKE

Tony Frewin was vexed. “I don’t want to get involved in the film industry,” he’d insisted yet again over eggs that morning. He loved his father, of course, but, like most teenagers, simultaneously found him exasperating. The old man had been harping about the same subject for weeks, insisting that he go in for an interview with some big-shot Yank at MGM British Studios in Borehamwood—Boreham Wood, actually; the frauds at the local council had conflated the two in some kind of ludicrous rebranding gimmick—and no matter how much he protested that he didn’t give a toss for British films, or American films, and was interested only in European ones—you know, the Nouvelle Vague, for God’s sake, or Bergman—Eddie Frewin wouldn’t take no for an answer. He kept insisting that Tony give it a shot, that he can’t spend all his time getting his arse thrown in the nick—three nights behind bars last time for want of a miserable few pounds, at the age of fifteen. Dad hadn’t been amused by that one, and nuclear disarmament be damned. Look, said Eddie, Tony needed to make himself useful, and stood to make a few quid besides, and, anyway, the American—goes by the name of Stanley Kubrick—had just made a film everyone thought was brilliant. It was called Dr. Strangelove. Had he seen it? Shot at Shepperton Studios.

This caught Tony’s attention. It was the first film by an American director that any of his friends had ever bothered with. In fact, practically the entire UK Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament had gone to see it, coast to coast, and they’d come away doubly determined to fight the global epidemic of insanity best boiled down to the acronym MAD—for mutually assured destruction, appropriately enough.

Actually, Strangelove had done more than that. It had shattered Tony’s picture of America. Everyone knew the country was insipid, stupid, silly, and complacent. So how could it have produced a film like this?

“Right,” Tony said to himself. “The only way I’m ever going to get Dad off my back is to go down for an interview.” Eddie bought Tony a pair of new shoes, drove him to the studio—it’s what he did: he drove to MGM, he drove from MGM; he was a studio driver—and went off looking for Kubrick. Leaving Tony here, now barely seventeen, on a September Sunday in an office in Building 53, a room that managed to be both cramped due to its low ceiling and big enough for a large central conference table with green baize on top—vaguely suggestive of card sharpery or gambling of some dubious sort—big enough also to contain upward of a couple hundred books, including large, full-color art books. Several of which Tony had taken down from the shelves lining the walls, since nobody had shown up to interview him. In fact, nobody had come in at all, apart from weekend cleaning staff in the form of one average-height, dark-haired guy in his thirties wearing baggy blue trousers, an open-necked shirt, and a rumpled blazer bearing evident signs of food stains and ash impacts. He’d entered, smiled in Tony’s general direction, and gone off again as Frewin sat there, quietly engrossed in the books.

And what books! They seemed to span every subject—though if you put your mind to it, a discernible pattern began to emerge. There was surrealism, futurism, cosmology, UFOs. There was a well-thumbed copy of a US Department of Defense Troop Leader’s Guide. There were dozens of science fiction novels. And there were stacks of magazines on every conceivable subject, from nuclear physics to computer science to psychology. “I wouldn’t mind working here just so I can get my hands on these books,” Frewin thought, turning the pages of Patrick Waldberg’s study of German surrealist painter Max Ernst.

The cleaner came back in again, and Tony thought to himself, “Shouldn’t he be off with his duster somewhere?”

“Listen, I’m sorry; you Eddie’s son?” he asked.

“Yes,” said Tony, startled.

“I’m Stanley. Stanley Kubrick.”

Jolted into action, Tony rose, and they shook hands. “Gee, you have a wonderful collection of books here,” he offered, gathering his wits. “Why’ve you got so many about surrealism, Dadaism?”

“Well, one of the problems I’ve got on this film is to come up with convincing extraterrestrial landscapes,” said Kubrick, sitting down. “As for Max Ernst, there are all sorts of ideas here. It might suggest something. For example, have you seen Europe After the Rain?”

“Yeah,” said Tony, regaining his seat, “it’s a dazzling painting.” It was pretty extraterrestrial, come to think of it. “Well, I’ve always been interested in that sort of thing,” he continued, like a man with more years under his belt.

“Really?” said Kubrick, extracting a small notebook and a pen from his jacket. “Are there any other artists I should be looking at?” He scrutinized Frewin inquisitively.

Nobody had ever asked Tony’s opinion about anything before. “Well, yeah,” he said. Apart from Ernst, the director might take a look at works by Giorgio de Chirico and Jean Arp. And he provided some other names as well. He’d first learned about surrealism four years previously upon reading George Orwell’s essay “Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dali.” Tony was from a working-class family, but he’d caught the wave and had been reading ever since.

Kubrick wrote down the names. He explained that the film he was working on concerned the discovery of intelligent alien life, and he asked if Tony had read much science fiction. “Yeah, I’ve read the novels.” Kubrick said that he had, too, and had also absorbed lots of pulp magazines when he was a kid, but he’d always thought that while the ideas could be wonderful, the characterizations were frequently shallow. “Most of the people are treated like robots,” he observed. As for the movies, “Cinema has let science fiction down.” Most sci-fi films, said Kubrick, were embarrassingly shallow and unconvincing, despite the fact that all kinds of interesting special effects techniques were now available.

Concerning extraterrestrials, the director was confident they were out there somewhere. The problem was the immense distances between the stars. These were so great that entire civilizations might rise and fall over millions of years without other civilizations ever knowing they existed.

And their conversation meandered on in this way for quite a while, covering evolution, the origins of consciousness, the future of human civilization, and other middlebrow topics. Soon two hours had passed, but still Kubrick didn’t seem to have anything better to do. In fact, he looked like he was enjoying himself.

Nobody had ever really spoken to Tony like a human being before, let alone bringing him directly into his innermost thoughts like that. In fact, thought Tony to himself, he’d been treated like shit, by idiots, ever since he’d left school. This was rather different.

Finally, Kubrick stood up. “I need a runner,” he said.

“When do you want me to start?” Frewin asked.

“How about seven o’clock tomorrow morning?”

“You’ve got a deal.”

Tony Frewin. Photograph by Stanley Kubrick.

And he never went back to his job as a temporary filing clerk at the baker’s union on Guilford Street.

• • •

MGM British Studios in Borehamwood, twelve miles north of Charing Cross station, was the most modern British film studio. Sometimes referred to loosely as Elstree, that being the name of the civil parish within which it was once located, it covered 114 acres, making it the largest studio complex in the United Kingdom. It boasted ten soundstages of various sizes, two dubbing theaters, five preview theaters, twenty-two cutting rooms, and processing facilities for all gauges of film stock between 16 and 65 millimeters. Green fields surrounded the complex, sometimes dotted with fluffy white flecks, as though a fine-point brush dipped in titanium white had touched down in the greenery here and there. Sheep.

Usually just referred to simply as MGM by its denizens, the studio’s expansive back lot was filled with large standing sets such as Asian and Mediterranean rural villages, a complete Boeing 707 fuselage with cockpit, a Battle of Britain–era Spitfire fighter plane that seemed in flight even while at rest, and a rusting, torpedo-like Japanese kamikaze flying bomb. When The Dirty Dozen set was constructed in spring 1966, a large French château rose to dominate a far corner of the complex, and kept on catching fire and exploding in the evenings for the benefit of that World War II drama, with no discernible ill effects visible the next day. Another corner was defined by a fifteen-thousand-square-foot water tank equipped with wave and wind machines, backed by a large billboard ready for whatever kind of nautical sky might be required, from tropical blue to gunmetal grey.

From the front gate, however, it all looked innocuous—a large white-collar industrial park of some sort, pleasantly accessorized in the English style with rosebushes and greenery, and featuring ample parking. Its most distinctive feature was a white two-story art deco central administration building with a square central clock tower about twice as high. Directly above the clock face were three words: Metro, Goldwyn, and Mayer.

At 5,437 miles from Hollywood, it wasn’t really far enough for Kubrick. But it would have to do.

It is difficult to exaggerate the extent to which 2001: A Space Odyssey would dominate MGM’s UK studios over the next two and a half years. Of the complex’s ten soundstages, nine would be used by the production, with a plurality reserved concurrently. Although the facility had been producing between ten and twelve films per year, it would manage less than half that for the duration of Kubrick’s production. Furthermore, MGM chief O’Brien had agreed that the complex’s considerable overhead costs would not accrue to the film’s budget. A big gamble, particularly given that Borehamwood was already considered something of a financial liability.

• • •

Building 53, MGM Borehamwood. Exterior. Late Summer, 1965.

A low, flat-roofed single-story prefab structure with twelve evenly spaced windows just to the right of the MGM administration building, Hawk Films HQ stands in front of the giant red-brick shoe box housing Stages 6 and 7. A sure sign that the doctor is in, Stanley Kubrick’s shiny new Mercedes 220 is parked directly beside his offices at the west end, in front of the Theater 3 entrance—a conveniently situated screening room where yesterday’s rushes will soon be scrutinized by the director every morning with something like the attention a brain surgeon pays to the next incision.

For all its capabilities, MGM didn’t have the largest stage in the country. That would be Stage H at Shepperton, another major British studio compound, south of Heathrow Airport. At 250 by 120 feet, Stage H had 30,000 square feet to play with and had been reserved by associate producer Victor Lyndon for use from December through early January. It’s where 2001’s immense TMA-1 set would be constructed—for Tycho Magnetic Anomaly 1, an alien artifact the size, shape, texture, and material of which was even now under intense discussion in Kubrick’s office.

The director wanted the alien object made of an absolutely clear material, a transparent tetrahedron that would materialize in Africa—because plans still called for the man-ape prelude to be shot there—and then be excavated on the Moon four million years later, meaning late December at Shepperton. Let’s make it in Plexiglas, Kubrick said, which you Brits call Perspex. Go forth and seek the best Perspex people in London, Masters, seek and ye shall find. And Masters said, Right, if that’s the decision, he’d look into it right away.

And fortuitously, a Perspex trade fair materialized in London that early fall. All the best manufacturers were there, and so was Masters—for an hour or so, anyway—evaluating. Finally, he approached the gent hosting the most impressive of Perspex sizes and forms. “I’d like you to make a large piece of Perspex for me, please,” he said.

“Oh yes, sure,” said the gentleman. “How big would you like it?”

“I’d like a sort of pyramid made in Perspex,” said Masters.

“Oh yeah, fine,” said the gent.

“I want it to be about twelve feet high,” continued Masters.

“My God,” replied the gent, somewhat put off. “That is a big piece of Perspex. May I ask what you intend to do with it?”

“Yeah, I’m going to put it on top of a mountain in Africa,” said Masters.

“Ah, well,” said the Perspex man, examining his interlocutor covertly to ascertain if anything in his expression provided grounds for the sudden supposition that his leg was being pulled. “Ask a silly question . . .” At this, Masters smiled cryptically. Kubrick demanded absolute discretion, and the designer wasn’t natively a blabbermouth anyway. “What’s the biggest piece you can make?” Masters inquired.

“Well, I’ve never made anything that size—I mean, nobody has,” said the gentleman, frowning thoughtfully. “But we’d like to do it. For various reasons, we can make it best in the shape of a pack of cigarettes, like a big slab.”

With this information still in his ear, Masters returned as swiftly as traffic allowed to Building 53, where he found Kubrick behind his desk. “Well, okay,” said the director, rapidly reevaluating his position. “Let’s make it that shape.” After several days of further discussions concerning height, dimensions, aspect ratio, and the like, off went Masters down the motorway again.

“It’ll take quite a long time to do the pouring and everything,” said the man at the fair. He was pleased, however, to see Masters again. This was what in the trade was known as a rather substantial commission. “And then it takes a month to cool, because it has to cool very slowly; otherwise it’ll shatter.” It would then have to be polished, also for quite some time—several weeks at least—in order that it be perfect.

A perfect piece of Perspex, the largest ever made.

And Masters brought it unto Kubrick. Before the director saw it, however, a crew set it up on a soundstage, directed lights upon it, and gave it a final polish. It looked magnificent, but it looked like a piece of Plexiglas. Masters and his deputy Ernie Archer went to inform the director that it had arrived.

“Oh, right, let’s go and have a look at it,” Kubrick said, rising from his desk. He accompanied them down glass-roofed pathways, up metal staircases, through soundproofed doors, and onto the stage area.

Three hominids approached the gleaming, brightly lit monolith. “Oh God,” said Kubrick. “I can see it. It’s sort of greenish. It looks like a piece of glass.”

“Yes, yes,” said Masters, “afraid it does—it looks like a piece of Plexiglas.” He’d unconsciously adopted the American term.

“Oh God,” Kubrick repeated. “I imagined it would be completely clear.”

“Well, it is nearly two feet thick, you know,” said Masters, frowning slightly. They contemplated the gleaming slab of greenish, refractive, reflective polymethyl methacrylate—over two tons of it. Several workers in blue overalls stood a slight distance away. Plexi. Lucite. Perspex. Whatever one chose to call it, it was not the magically ultraclear, almost invisible alien artifact of Kubrick’s imagination.

“Ah,” he sighed regretfully. “File it.”

“Do what?” Masters asked incredulously.

“File it,” Kubrick repeated.

“Oh,” said Masters. “Okay.” He turned to the workers. “Take it away, boys.”

As to the expense, one of Stanley’s young assistants would later estimate that it cost more than a fair-sized home within Greater London.I Masters and Archer accompanied the director back to his office.

“I don’t believe it,” Kubrick said ruefully. “It looks like a piece of glass.”

“Well, I’m afraid it does, yes, you’re right there,” said Masters, who had a reputation for thinking nimbly on his feet and devising alternate solutions with great rapidity. “So, let’s just make a black one, because then we won’t know what that is.”

“Okay, make a black one,” said Kubrick.

The size, shape, and color of 2001’s monolith had been established.

• • •

Clarke’s homecoming in Colombo lasted only a month or so, long enough to cover the usual bounced checks, see to it that Mike Wilson had adequate financial resources to start shooting his next film—a James Bond parody officially titled Sorungeth Soru but often referred to simply as Jamis Bandu, featuring the adventures of the eponymous Sinhalese secret agent—catch up on his mail, and hop a jet bound for London.

Arriving at Elstree on August 20, he discovered that Kubrick had been so worried when NASA’s unmanned Mariner 4 spacecraft had flown by Mars a few weeks previously that he’d contacted Lloyd’s of London and asked the insurance company to draw up a policy to compensate him if their plot was demolished due to the discovery of extraterrestrial life. “How the underwriters managed to compute the premium I can’t imagine,” Clarke wrote wonderingly, “but the figure they quoted was slightly astronomical, and the project was dropped. Stanley decided to take his chances with the universe.”

Throughout the year and well into 1966 and actual production, Kubrick and Clarke remained enmeshed in seemingly perpetual story development. Despite their best efforts, the film’s ending was repeatedly deemed unsatisfactory. As of August 1965, an “unbelievably graceful and beautiful humanoid” was supposed to approach Bowman, the crew’s sole survivor, and lead him into “infinite darkness.” How to achieve such grace and beauty had been left indeterminate. In any case, it wasn’t just inadequate, it flirted with risibility. Kubrick didn’t do risible.

Earlier in the year, they’d decided that astronaut Frank Poole, Bowman’s sidekick, would need to die in an accident. This would spice up the journey to Jupiter, but the exact nature of the accident was in flux, and even the finality of his death was sometimes in question; one Clarke journal entry had him “fighting hard to stop Stan from bringing Dr. Poole back from the dead. I’m afraid his obsession with immortality has overcome his artistic instincts.”II In May, Clarke had devised a scene where Poole’s space pod smashes into Discovery’s main antenna, breaking their link to Earth and sending both antenna and Poole spinning off into space. What had caused the accident wasn’t yet clear, however. The spacecraft’s computer, then named Athena, after the goddess who’d helped Odysseus out of many a scrape, wasn’t yet fully developed as a character.

Soon after Clarke’s return from Ceylon, Kubrick told him he’d devised another plot twist in which Poole and Bowman, the only two Jupiter-bound astronauts not in suspended animation, had been kept in the dark about their mission’s true purpose. According to his new idea, only the “sleeping beauties” locked away in Discovery’s sarcophagus-like hibernaculums had been informed that they were seeking contact with intelligent extraterrestrial life—and they weren’t supposed to be revived until arrival at Jupiter.

While Clarke wasn’t particularly pleased by Kubrick’s revision, he also wasn’t happy that he hadn’t been able to come up with a mutually satisfactory ending. On the twenty-fourth, he produced a two-page, nine-point memo. “I’ve put my finger on a flaw that worried me,” he wrote Kubrick. “It’s simply insulting to men of this caliber to assume they can’t keep a secret that hundreds of others must know. Also it introduces an unnecessary risk.” In response, Kubrick had scribbled, “You can construct just as logical a reason for it if you try.” Clarke: “This element of suspense rather artificial and improbable.” Kubrick: “Don’t agree. Only if you fail to try to make it work.”

He wasn’t giving an inch.

A day later, Clarke conceived of yet another new ending to the film in a second message, written from his brother’s house on Nightingale Road.

It’s amazing how long it takes to see the obvious. The weakness of our ending was that we never explained what happened to Bowman, but left it entirely to the imagination. Well, we can’t explain it—but we can symbolize it perfectly in a way that will push all sorts of subconscious and even Freudian buttons . . . Remember the beautiful little spaceship Bowman sees on landing? We used it merely to draw a contrast with Earth’s primitive technology. Well, after his processing in the hotel room, Bowman will be master of new sciences. The narration tells us this—the visual effects prepare us emotionally—but we will only believe it when the room vanishes, and he is alone on the skyrock with the ship of the super-race—and his own Model T space pod. The ship is man’s new tool—the equivalent of Moonwatcher’s weapons. It symbolizes all the new wisdom of the stars. Bowman—with one backward glance at the pod—walks toward it. As if in greeting, it rises a few inches as he approaches. Close up, the hull texture must be beautiful (soft? warm?). He stands thoughtfully beside it, looking up at the sky and the road back to Earth. As he does so, he strokes it absentmindedly, almost voluptuously. (Appeal of fine sports car, camera.) “Now he was master of the world, etc . . .” The End

It would pack “a hell of a punch,” he concluded, “and I’m sure it solves all our problems.”

We don’t know what Kubrick may have thought of Clarke’s soft, warm Freudian spacecraft that rises “a few inches” in expectation of being stroked, but the director’s terse response only extended an emerging split between their two approaches: “I prefer present nonspecific result for film. Maybe this can work in book but it won’t on film.”

He didn’t do risible.III

• • •

Sets, meanwhile, were being assembled at a furious clip. Masters and Archer coordinated with art director John Hoesli and one of the best construction managers in England, Dick Frift, to build spacecraft interiors of unprecedented complexity, and these were starting to dominate Stages 2, 3, and 6. The floor of Stage 4, meanwhile, was being torn up and reinforced so as to bear the weight of the immense centrifuge set, then being prepared offsite by UK aviation firm Vickers-Armstrongs—makers of the famous RAF Spitfire, a representative of which was parked in the back lot, waiting for the Luftwaffe to return.

By now, the design team first assembled in New York was working together seamlessly and collaborating with Roger Caras, who’d remained in Manhattan for the time being, where he could interface more easily with major American corporations and seek their input into technological concepts and designs until the shooting started. After that, he would move to London. Masters’s staff of forty architects, set decorators, model builders, and prop designers was spread across a network of workshops. Together they designed, built, furnished, and finished a unified vision of the future.

One key to the film’s extraordinarily believable mise-en-scène—its overall “look”—was this coordination between technology-producing industry—which included leading industrial designers such as Eliot Noyes, the architect of IBM’s integrated corporate visual identity and also its innovative Selectric typewriter—and the production’s tripartite design leadership, with Ordway ensuring absolute technological plausibility based on corporate and governmental research and development, and Lange combining that with his extensive knowledge of space technologies to police the look of the sets and models and bring a sense of style to it all. Lange, said Masters, “put the authenticity into it.”

To the extent that a division of authorship existed in such an intensely collaborative project, it was Masters who came up with kinetic concepts such as the rotating sets and designed the interiors and props, and Lange who did the vehicle and space station exteriors, as well as the film’s extraordinary space suits. But in fact everyone worked on everything together, with lots of cross-pollination during meetings and discussions. Special effects pioneer Wally Veevers, who’d done the miniatures in Dr. Strangelove, would supervise the actual model production and filming, among other things. “The strange thing was that we all worked together for so long that we began to design in the same way,” Masters recalled in 1977. “Just like Georgian or Victorian is a period, we designed 2001 as a period. We designed a way to live, right down to the last knife and fork. If we had to design a door, we would do it in our style.”

On top of this, Masters and Kubrick weren’t above using compelling work by outside designers, which simply had to conform to their vision of what the early twenty-first century would look like. These included dozens of futuristically curvaceous scarlet Djinn chairs, designed by Olivier Mourgue in 1963, which livened up the otherwise monochrome interior of Space Station 5, and several examples of Eero Saarinen’s 1957 Tulip table. Geoffrey Harcourt’s chrome-and-leather lounge chairs furnished the Clavius Moon Base conference room.

Complicating everything was the endlessly mutable story line. Despite the gargantuan nature of the undertaking—the giant, complex sets, the big budgets, the risk MGM was taking, the fact that a major studio complex with thousands of employees was almost entirely devoted to realizing his vision—Kubrick was winging it. The project was all in his head. In a normal head, of course, this would be a recipe for disaster. What began to emerge from his head, however, was actually a form of refinement. For all the seeming chaos, dross was methodically being stripped away and messages refined.

“We weren’t working to any particular schedule or even any particular script,” said Masters. “We had a basic idea—which was, of course, Arthur Clarke’s story—but we never had a finished script. We worked through the movie, changing every day our ideas of what we were going to do tomorrow.”

We’d get together with Stanley in the evening and talk about what we were going to do the next day—and as a result, the whole thing would change. The production department was suicidal. Because, daily, absolutely everything that had been planned would be thrown straight out the window; we’d do something completely different. And that was how we worked from day to day. Having got through that particular problem, we’d then say, “Well, what are we going to do tomorrow?” but, in fact, when we came to it, he’d say, “Oh well, the hell with that, let’s do something really interesting.” And out of it—out of talk and talk and talk came something really much better than we thought we were going to do.

To add to the confusion, despite being a profoundly visual thinker, Kubrick was nearly incapable of actually picturing visual concepts when they were described verbally. He also didn’t necessarily know what he liked until he saw it, and so he needed to be given several choices. These characteristics served to delay and sometimes confound many an idea conceived by the design department.

With most of the sets ostensibly depicting vehicles in a weightless environment, and with so much of the action centered on the turning, artificial-gravity-producing centrifuge at the center of Discovery’s spherical front end, several of the sets needed to rotate with a flawless smoothness. Masters conceived of a design permitting movement of the astronauts from the weightless part of the spacecraft to the centrifuge. In the final shot, they would proceed down a corridor, at the end of which was a rotating wall with a ladder. On reaching the end, they would seamlessly transition to the turning element—and, from an audience perspective, magically proceed to spin 360 degrees as they climbed out of the frame, thus “descending” into the centrifuge.

In order to accomplish this sleight of vision, however, both the entire corridor and the rotating wall and ladder assembly had to be mounted on external frames such that each could turn smoothly within armatures packed with ball bearings. “To capture that, we had a camera at the end of the corridor, screwed to the deck,” Masters recalled. “The men walked away from us toward the revolving set, and as soon as they stepped onto the drum, we stopped it and began revolving the corridor.”

But because the camera moved with it, you couldn’t see any change at all. On the screen, it looked like the end was revolving all the time and the men were going around with it . . . and they just went through a hole in the bottom of the thing. So that was two revolving wheels—one was revolving at the end, and then that one stopped and this one had to start revolving. And the mechanics of that, to get it to just the right moment, you had two levers, and as [they] stepped on, you had to go arrrgh with these great things—these were huge, great, massive sets revolving and rumbling around—it really worked well.

When all this was first explained to Kubrick, however, for all his legendary acuity, he just didn’t get it, and Masters spent a marathon session one night in the fall of 1965 sketching away at a blackboard in the director’s office, in an increasingly desperate attempt to convey the essence of the two elements. Finally, at about one in the morning, Kubrick said, “I think I see it! I think I know what you mean.”

“Sweat was now running off, you know,” the designer recalled. “Thank God for that—I won that one. But oh, was it hard going.”

In the end, Kubrick loved the shot, which, despite the complexity behind it, unfolds with a seemingly effortless, antigravitational simplicity.

• • •

Harry Lange’s transition from German to English life via a two-decade interlude with von Braun in the American Deep South didn’t come without bumps and jolts. Nothing he’d seen in Alabama particularly disturbed certain attitudes that he’d absorbed in the fatherland, and though he was universally well liked by those who worked directly with him, that left most of MGM’s substantial staff, who were not without memories of the Luftwaffe’s blitz on major English cities in the early years of World War II. What they saw was a German man showing up to work in a quasi-militaristic “Janker” hunting jacket with stag-antler lapel details—the kind of “Tracht” traditional garments associated with Hitler, Austria, and Bavaria. As though willfully seeking to accentuate this effect, Lange—a man of some means following his marriage to a Huntsville heiress—had plunged into equestrian pursuits soon after his arrival. As a result, he also favored riding boots that, minus the Janker gear, would have looked a bit less like Prussian jackboots and more like standard British foxhunting attire. With them, however, they bore certain unfortunate connotations.

Harry Lange in his studio at Borehamwood.

How conscious all of this was is open to debate. Christopher Frayling, author of an excellent monograph on Lange, believes the designer may have been “making a joke of it . . . perhaps subtly trying to ‘lay the ghost’ . . . by bringing the culture clash out into the open.” If so, the designer forgot all subtlety when he brought a scale model of a V-2 rocket into his office one day and positioned it on his desk, where it existed in uneasy resonance with the Confederate flag he’d already pinned to the wall. Von Braun’s “vengeance weapon” had killed more than two thousand people in London alone during the closing months of the war, and word of Lange’s provocation spread rapidly, triggering a walkout of the British design staff. A swift intervention by Kubrick made the model and flag disappear, however, and gradually MGM’s designers returned to their desks, still muttering and casting glances.

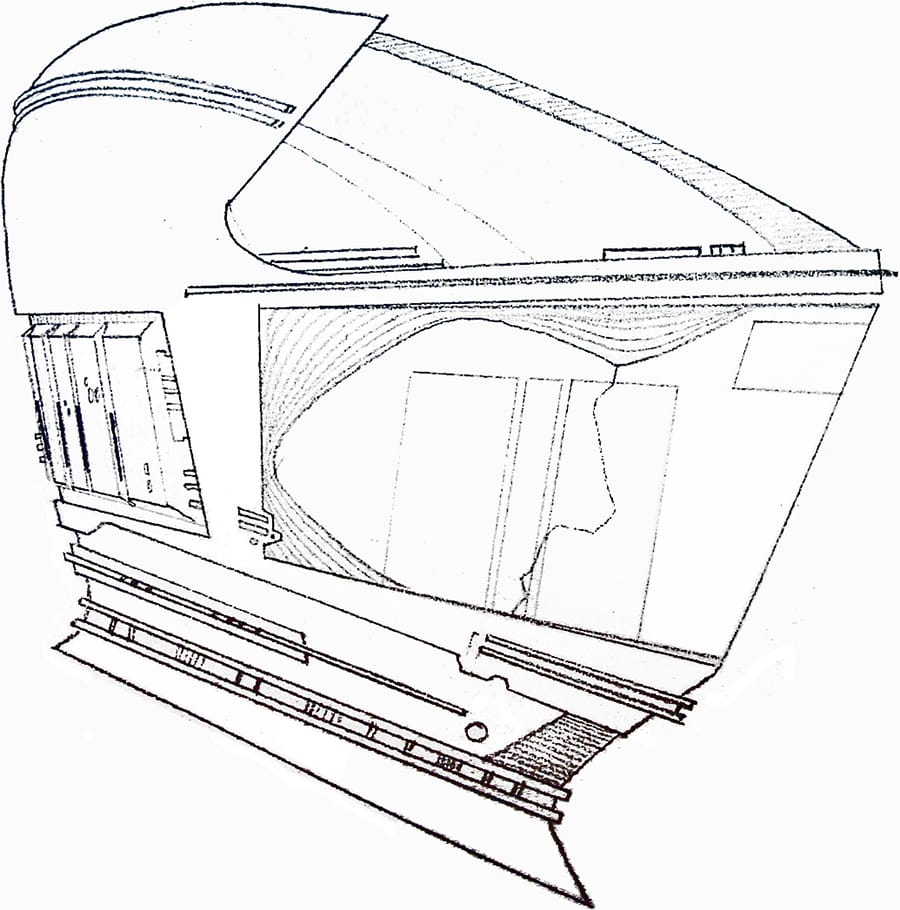

Lange’s space helmet design.

Whatever his politics, one thing that you couldn’t take away from Lange was the impressive new space suit designs he’d finalized that fall, just in time for the aptly named Manchester company, Frankenstein & Sons, to produce them. What Frankenstein delivered, however, still required accessorizing with all the details necessary to bring them to life, so to speak—for example, the addition of backpacks, front maneuvering controllers, button panels for the arms, and, of course, the helmets—which were produced either at Borehamwood or by AGM, the London company also busy manufacturing “Daleks”: the cylindrical alien cyborgs seen in Doctor Who, the cult BBC-TV series.

Lange’s suits came in two models. The silver, lunar versions were slightly different from Discovery’s multicolored deep-space EVA (extravehicular activity) suits. The latter had large silver air hoses looping, not unlike scuba regulators, from their backpacks to the base of their helmets—a design flaw thoughtfully added at the last minute as Kubrick and Clarke refined the nature of astronaut Frank Poole’s upcoming accident.

Lange would spend the rest of his life working as a film designer in the United Kingdom, and it was 2001’s extraordinary space helmets that perhaps best symbolize his transition from an Austro-Bavarian to a more acceptably British frame of reference. After multiple drawings of rounded designs—all of which ended up looking too similar to motorcycle crash helmets—his final design was based on the oval, forward-thrusting shape of a certain species of British hunting cap, the men’s Ascot riding hat.

• • •

A good sense of Roger Caras’s emerging role as Kubrick’s most trusted advisor and confidant—a kind of New York counterpart to his LA fixer Louis Blau, only with professional PR smarts—can be found in a telling exchange in late July concerning IBM’s advice on how to present Discovery’s talking computer, Athena. Kubrick had been expecting ideas concerning computer input and output devices and was unprepared for what he actually received from the company. In a cover letter to a document from Eliot Noyes’s influential design bureau think tank—one that included drawings of astronauts floating within a kind of “brain room”—Caras wrote, “As you can see, they say that a computer of the complexity required by the Discovery spacecraft would be a computer into which men went, rather than a computer around which men walk. This is an interesting idea, and if the plan for the Discovery will accommodate this, you may want to consider it very carefully.”

The communication caught Kubrick in an uncharacteristically defeatist frame of mind. “[T]he IBM Athena drawings are useless and totally irrelevant to our needs and what I must presume were Fred’s discussions with IBM,” he responded, referring to Ordway. “I’m extremely bored and depressed with all this.” He proceeded to list what IBM should really help with—including “detailed design concepts” (although the company had provided just that). “There is absolutely no time to waste,” he concluded. “Even having to write this letter adds chips to what seems to me to be a completely lost hand. I know this is not your fault or Fred’s, and don’t take this as criticism of yourselves. It is merely a total fuckup which not only fails to do what was hoped for but costs time.” He signed off in caps: “Annoyed and depressed but lovingly, S.”

In fact, IBM’s recommendation couldn’t have been more salient, and would eventually result in the construction of Discovery’s Brain Room—location of perhaps 2001’s most extraordinary scene, when astronaut Dave Bowman lobotomizes the ship’s computer, by then named HAL. But first Kubrick had to chill out, reconsider, and let the dramatic possibilities form in his imagination.IV

Other letters transmitting advice to Kubrick and his design trust in London also tapped the thinking of some of the finest futurists then working, and were equally critical to the film’s final look. As a by-product of Kubrick’s and Clarke’s questing, cerebral commitment to scientific and technological accuracy, a big-budget Hollywood production had been transformed into a giant research and development think tank. A sustained campaign by Ordway and Caras to interest leading American technology firms in participating—largely in exchange for product placement within the film’s sets and mention during its promotion—was paying off.

A sampling of their letters written in July 1965 alone reveals they covered such diverse topics as mammalian hibernation; space suit designs; lunar charts; lunar photography from major observatories; interplanetary nuclear propulsion; information about Jupiter, Saturn, and their moons and rings; communications systems of many kinds; scientific equipment to be used on the Moon and at Jupiter; photos of the Earth from “balloons, missiles, and satellites”; and countless other themes. Apart from IBM, companies approached included Hilton Hotels, Parker Pens, Pan American World Airlines, Hewlett-Packard, Bell Labs, Armstrong Cork, Seabrook Farms, Bausch & Lomb, and Whirlpool. The number of firms consulted ultimately topped forty.

In the summer of 1965, Kubrick received two detailed Bell Labs reports written by A. Michael Noll, the digital arts and 3-D animations pioneer, and information theorist John R. Pierce—coiner of the term “transistor” and head of the team that built the first communications satellite. They recommended that Discovery’s communications systems feature multiple “fairly large, flat, and rectangular” screens, with “no indication of the massive depth of equipment behind them.” Flat screens were, of course, unknown, at least outside of movie theaters, in 1965. Incorporating them within the production’s set designs helped ensure 2001’s futuristic sheen and gives it an eerily predictive, contemporary feeling even today. A single piece of advice from two of the best minds in the business helped bring about the film’s prescient portrayal of our screen-based future.

As Kubrick’s conception of Athena’s role in the story evolved, his advisors’ communications with IBM started hinting at the computer’s transformation from a reliable but somewhat dense crew assistant to something rather more complex. Noyes and company’s suggestion that crew members could physically move about within Athena had also suggested certain possibilities—at least, once Kubrick got over his initial aversion. Conflict being the essence of drama, as of August 20, the director was already contemplating that Athena cause the death of one of the hibernating crew members, V. F. Kaminsky.V

On August 24—the same day Clarke questioned the need to keep the waking crew ignorant of the mission’s true purpose—Ordway wrote a somewhat guarded mail to IBM executive Eugene Riordan. In a tone indicative of the need to extract information without risking corporate alarm, he sought advice on “quasi-independent” actions that “conceivably could be taken” by the ship’s computer. “Let us look down the road to the year 2001,” Ordway wrote. “Do you think that by that time computers will be able to think, so to speak, somewhat to themselves and to initiate any actions that are not strictly according to the programming?”

Suppose in the interest of secrecy, that some important mission information was made known to the vehicle commander and not to the rest of the crew. Because the crew had access to Athena, this information could be stored in her. Yet she would be aware that certain flight procedures were being taken in a manner inconsistent with the information available to her. Take another possibility that occurred to us. Could Athena become slightly hypochondriacal, reporting rather more than necessary—not to be overdone—that this or that circuit or device should be checked for malfunction or impending malfunction? It would have to be very consciously presented at a threshold that would barely raise the suspicions of the mathematicians and computer specialists aboard. Athena might also exhibit aggressions, of a mild type, that would somehow be manifested.

IBM’s cooperation thus far had been predicated on an agreement that the company logo be visible on various of the film’s technologies—and indeed it’s seen throughout, including on Discovery’s iPad-like tablet computers. By October, however, those “slightly hypochondriacal” symptoms had clearly worsened to the point where another mail to Riordan was in order. This time Ordway informed the executive that Discovery had been “evolving” into “a considerably more experimental vehicle than originally visualized.” Several “interesting plot points” had become feasible involving, in some cases, malfunctioning equipment. “Naturally, we do not want to present any IBM equipment in such light,” Ordway wrote. Accordingly, they had decided Discovery’s computer would be labeled “as an experimental research and development type, recording only its number and the name of the sponsoring government agency.”

The new name Kubrick and Clarke ultimately settled on compounded two terms, signifying a Heuristically programmed ALgorithmic computer. The terms behind the acronym, and possibly the acronym itself, were originally suggested by Marvin Minsky, cofounder of MIT’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. “Heuristics are, of course, rules of thumb; tricks or techniques that might work on a problem, or often work, but aren’t guaranteed,” Minsky commented in 1997. “Algorithmic implies inviolate rules, such as If A then B, and A, therefore B. HAL was supposed to have the best of both worlds.” This duality between algorithms and heuristics—between dogmatic rules and interactive, trial-and-error paths to a solution—already hints at the core conflict that HAL would experience when asked to keep the mission’s true purpose from the waking astronauts.VI

On October 12, HAL was still Athena, but Clarke alluded to the emerging dramatic possibilities in a note to Kubrick: “If we wish, we can make the ‘accident’ an integral part of our theme, not just an episode inserted for excitement. After all, our story is a quest for truth. Athena’s action shows what happens when the truth is concealed. We should delicately underline this at the appropriate point.” The computer’s internal conflict when asked to lie to the crew would be made more explicit in Clarke’s novel than in the film, though certainly it’s there in later script drafts and also in dialogue Kubrick filmed but ultimately didn’t use.

An intriguing set of notes from late October survives in Kubrick’s hand, a kind of Rosetta stone in which the director grapples with how to convey the computer’s dilemma: that of being programmed to deceive the crew despite having been created expressly to provide them with flawless, objective data. “One evening (or whenever Poole’s sleep cycle is), he brings up a rumor he heard prior to departure. He is semiserious,” Kubrick wrote. “Rumor was that there was a secret aspect of the mission that only the sleepers knew, and that was why they were trained separately and brought aboard already asleep.” The two crew members discuss this “fantastic possibility”—which the director compared with “rumors of high-level CIA men being involved in [the] Kennedy assassination”—and finally decide to ask the computer. “They do so as a joke (but obviously covering real interest) . . . The computer says, ‘No.’ There is a devilish, perverse humor about it . . . the imp of the perverse.”

The imp of the perverse. That Kubrickian signature, surfacing as a note to self.

He also hit on the idea of chess—stylized combat, after all—as a way of conveying the computer’s emerging deviancy. Both Bowman and Poole could play Athena, he suggested, and realize gradually that they never win, “even when they play over their heads with chess books.” Since she was programmed to lose half the time, Kubrick wrote, this “should immediately be recognized as a minor programming error; not serious but needs to be watched.”

Aspects of these scenarios found their way into the final film, but one further intriguing element was discarded. Bowman was envisioned working with Athena when “suddenly computer asks about paradox all Cretans are liars. Or puts up an illusion and asks Bowman to define an illusion.”VII And he wrote Bowman’s response: “You seem very interested in illusion. You asked me this several times during the past week.” Kubrick also envisioned that both crew members would gradually become aware they were being monitored at all times by the computer.

On the fourteenth page of his handwritten notes, under the heading “Killing the Computer,” Kubrick arrived at a moment of sheer intuitive insight. It appeared as a sentence fragment so formally empathetic with its subject, it is as though he’d momentarily assumed the role he was conjuring: “Computer tries to talk Bowman out of erasing—incapacitating it—slowly become more + more”

There’s no ellipsis, and the sentence never ends. He’d already moved the searchlight of his mind on to the next thing.

• • •

Doug Trumbull had been suffering acute withdrawal pangs that Los Angeles summer. After painting the rotating galaxy for To the Moon and Beyond—the experimental Cinerama short film that had impressed Kubrick at the 1964–65 World’s Fair—he’d worked for a few months on exactly the kind of thing that he loved: namely, drawings of moon bases, spacecraft, and landing pads, and it had been like a steady dopamine drip to the brain. But Kubrick had moved farther east, cutting Graphic Films loose in the process, and with less work to do, the company had been forced to let him go. Trumbull had been into science fiction since he was a child, and although he’d started a little furniture company in Malibu to augment his income, it wasn’t really where he saw himself.

He called his erstwhile boss, Con Pederson. It had been really exciting working on the Kubrick space project, he said. How could he contact the producer? Pederson explained that a confidentiality clause in his contract made it hard for him to say. There was an awkward pause. They’d worked well together on a couple projects, including To the Moon and Beyond. “Look,” Pederson said finally. “If you went down to the office, you just might, maybe, find Mr. Kubrick’s phone number penciled into the corner of the bulletin board.”

Trumbull had gone in the back door of Graphic, bypassing the receptionist, so many times it was practically a reflex. Now he wasted no time repeating the move, found the number, took it home, calculated what time it was in London, and dialed. With no secretarial intervention, the director picked up immediately, and Trumbull introduced himself. “I’m one of the illustrators that’s been working on the drawings you’ve been getting, and I want to go to work on your picture,” he declared. Apart from his work on To the Moon and Beyond, he detailed his other qualifications as well. While that didn’t take particularly long, his previous projects had all been seemingly perfectly attuned to 2001’s subject matter and requirements.

“Absolutely great,” Kubrick replied. “You’re on, you’ve got a job—come on over . . . I’ll pay you four hundred dollars a week.” Hawk Films would arrange plane tickets for him and his wife, and find them accommodations as well. Welcome aboard. Was there anything else?

On arrival in mid-August, Trumbull, a fresh-faced California kid in a cowboy hat on his first trip out of the country, discovered so much activity going on at Borehamwood that he was afraid he’d gotten there too late. “I was twenty-three at the time and didn’t know anything, really—just a little bit about animation and background painting. I didn’t even understand photography very well. Before I left for England, I bought a Pentax camera, and when I got there, I started fooling around with a little black-and-white darkroom at home, just learning the fundamentals,” he recalled.

He needn’t have worried. There was plenty left to do—live-action production hadn’t even started yet—and in the next two and a half years, Trumbull would rise from grunt animator to become one of 2001’s four leading effects supervisors, leaving a distinctively innovative visual stamp on the film in the process.

• • •

2001: A Space Odyssey was an analog-to-digital undertaking from the beginning. The projected ubiquity of computer motion graphics decades in the future had been internalized by Kubrick and his designers, but because the kind of processing power needed to drive the incoming information age wasn’t yet available, it would all have to be done by hand.

Trumbull had been a painstaking painter of cells for animations at Graphic Films, and Kubrick and Wally Gentleman gave him a day to shake off the jetlag before they put him to work. He was charged with making the computer readouts that would wink, jostle, and whizz purposefully about on all the flat screens being built into the sets, each of which had room behind it to hide a “massive depth of equipment,” as Bell Labs had put it, in the form of a Bell & Howell 16-millimeter film projector. These included the ostensibly handheld tablet computers, which would actually be permanently affixed to the tabletop they appeared casually placed on top of, with projectors concealed behind them.

The screens themselves were opaque ground glass, perfect for rear projection. The Honeywell corporation had advised that what was to unfold on these ubiquitous displays should include headings such as Computer, Life, Radiation, and Propulsion—a cycling of systems critical to Discovery’s functioning. Otherwise Trumbull was given wide latitude to determine their contents; it simply needed to look authoritative and credible. Some animations would be more central to the shots, however, and would have more precisely programmed content, such as a navigational screen in the Orion space-plane cockpit, which would depict a rotating three-dimensional graphic display of Space Station 5’s central rectangular docking port.

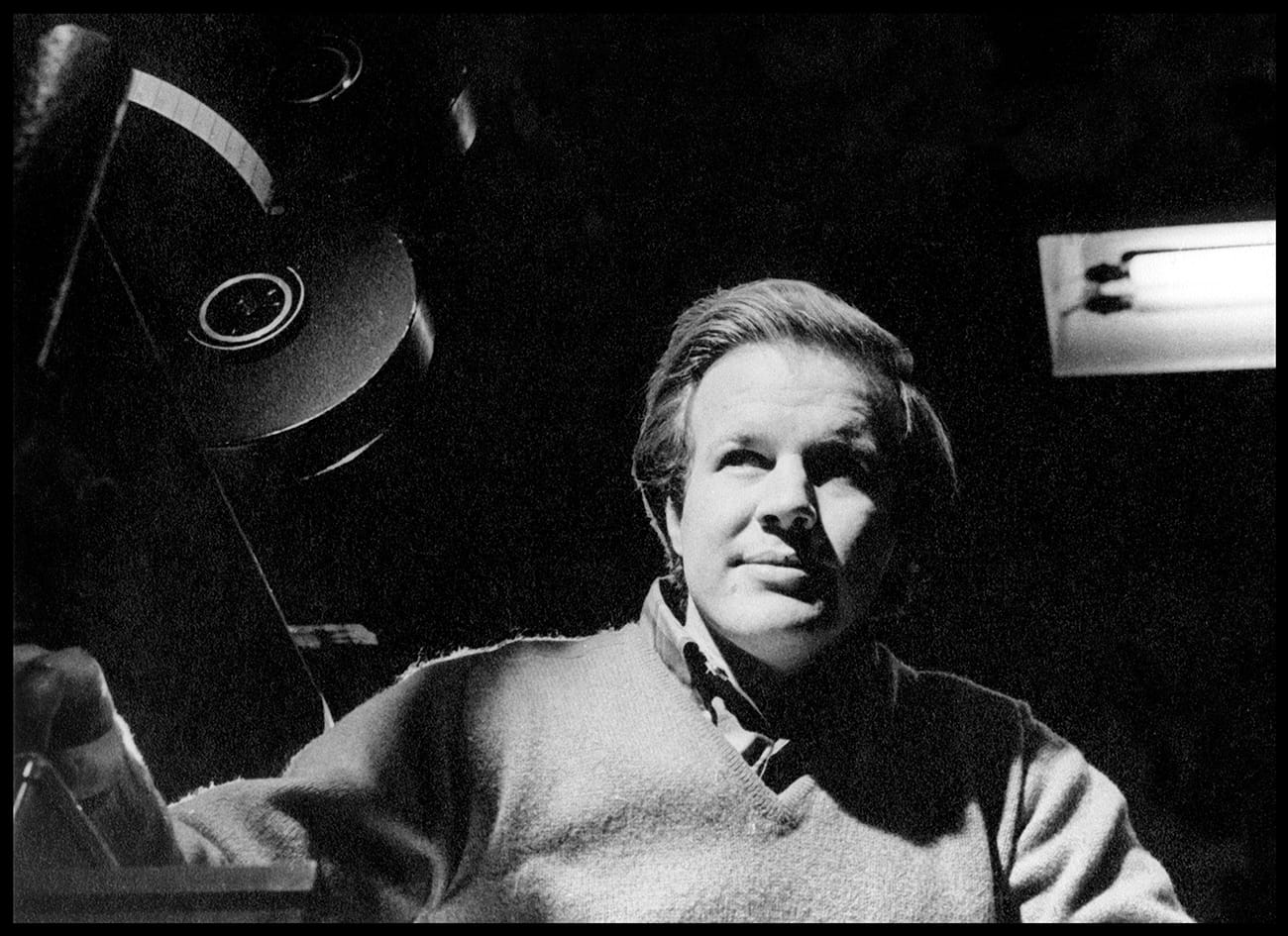

Doug Trumbull at Borehamwood.

Friction had been building inexorably between Gentleman and Kubrick ever since they arrived in England. The former was alarmed by what he saw as a needless waste of resources, money, and time, and critical of what he saw as the director’s pigheaded insistence on testing techniques Gentleman already knew wouldn’t work. The latter was increasingly irritated at his collaborator’s resistance to his ideas and what he regarded as a know-it-all manner. “Wally was a very scientific, linear, very elegant, very gentlemanly, very erudite, very well-trained, and experienced guy,” Trumbull recalled. “And Kubrick was very freewheeling: ‘Whatever everybody’s doing, I’m doing just the opposite’ kind of thing. And I think it just kind of rubbed Wally the wrong way.”

For his part, Trumbull was honored to be working with one of the visual innovators behind Universe, which he’d seen at Graphic Films, and which had been screened for him again immediately on his arrival at Borehamwood almost like a form of freshman orientation. Gentleman noted with approval that Trumbull was absolutely unintimidated by the director. “Doug would sort of wander onto the set and, with all the ingenuity and ingeniousness of a young man, would state exactly what he was thinking at the time,” he said. “And this kind of nettled Stanley to begin with, but he gradually got used to it. But Doug was really working from a strongpoint of authority because his work was so very good. And I think he made the greatest contribution, finally, to the film of anybody.”

Their early conception of a visual effects production chain had been to farm out the animation and model making to external companies, so Trumbull set about using traditional numbered animation cue sheets and creating artwork for the displays. It took only a few days of this for him to understand that conventional techniques were simply too labor intensive, and that their subcontractor, an animation service near the studio, was simply too slow. “Wally said, ‘We can figure out a better way to do this,’ ” Trumbull recalled. “Because he was completely fearless. And he said, ‘Let’s build our own animation stand. Screw these guys. We’re going to do it our way.’ ”

They cannibalized an old Mitchell single-frame movie camera from an optical printer, built a stand from a scaffolding made of pipes and clamps—the ubiquitous Borehamwood rigging material also used for sets and scenography, lumber being expensive in England—and started animating at a rapid clip. Trumbull recruited an energized teenager, Bruce Logan, directly from the animation service they’d just dropped and put him to work. Their telemetry displays were taken from “a million random sources of neat-looking graphs”: Scientific American magazine, NASA manuals, and the like. These were xeroxed and then photographed as high-contrast stats, or negative transparencies.

Trumbull also devised an ostensibly high-tech language of letters and numbers to convey Discovery’s supercomputer data-stream, laced with “strange little acronyms and funny little three-letter fake words and things,” typed it up on an IBM Selectric, and made more high-contrast transparencies. All this was funneled onto the glass plate in front of the Mitchell as he and Logan blasted rock ’n’ roll at all hours of the day and night. “We’d sit there on the animation stand cranking out enormous volumes of footage, one frame at a time,” he remembered in 1976. “We’d shove this stuff under the stand and line it up by hand, put a red gel over it, shoot a few frames, then move it around and burn in something else or change some numbers. It was all just tape and paper and colored gels.”

Hitting their stride, they managed to produce ten minutes of readouts a day—a pace practically unheard of in animation—all of it intended to provide the impression that the computer was processing an “autonomous, twenty-four-hour-a-day deluge of data.” It was a triumph of youthful enthusiasm over the old, time-consuming way of doing things, and they brought it off without visible compromise. But “In reality, it was a kind of high-tech window dressing,” Trumbull said.

Maybe so, but their evocation of endlessly hosing data—a nonstop stream of seemingly authoritative info-graphics, equations, acronyms, and letters—gave pulsing, almost capillary life to the computer running Discovery and the scrupulously engineered world in which 2001’s story unfolded. No less critically than the design team’s creation of a futuristic period equivalent to Georgian or Victorian, it conjured an entire upcoming chapter of civilization.

• • •

The studios at Borehamwood were stratified into what amounted to a rigid, union-enforced caste system, in which designers weren’t supposed to pick up a screwdriver in case they threatened machine shop jobs, and set builders weren’t to be seen applying a pencil to a blueprint for the same reason—at least in theory. As a faux cowboy from California with a genial manner and disarming grin, Trumbull was conspicuously sui generis, however, and he soon discovered that his outsider status came with huge advantages. American film workers were able to work at MGM in the first place because of a loophole in a British film subsidy program called the Eady Levy—essentially a tax on box office intended to keep the local industry alive by luring US studios with substantial tax breaks. As a result, UK production was cheaper than in the United States—one reason, of course, why Kubrick was there and why he’d shot his previous two films in England as well.

The Eady cap on non–UK citizens or legal residents limited the number of Americans who could work on 2001 to 20 percent. But because Trumbull didn’t need to qualify for union membership under Eady, he discovered that he could go directly to department heads without bureaucratic obstacles—for example, to the guy running the machine shop, to request that parts be made for his new animation stand. He would use this freedom to fullest advantage over the next two years.

Kubrick, of course, had his own bigger-picture workaround. Simply by virtue of geographic distance, he’d seen to it that MGM had very limited abilities to intervene in his production. “There was no studio management interference at all,” Trumbull recalled. “We were doing new things all the time. It was a free-wheeling situation where there was no schedule, no budget, no delivery date, and we were just going to solve all these problems, one after the other, as they came up. You know, the movie’s trundling ahead. They’re building sets. They’re building all their props. They’re building their miniatures. And every time something would come up, Stanley would say, ‘Well, Doug, what can you do to help me fix this thing?’ ”

One thing he helped fix concerned miniature work. Soon after Trumbull and Logan got their animation stand rigged, a London company called Mastermodels delivered a three-foot-long Moon Bus—the first of several spacecraft they’d been contracted to make. At a glance, Trumbull realized it simply wouldn’t do. The thing looked like a fiberglass travel agency display, not a credible piece of engineering. Having been essentially an illustrator up until that point, he was skilled with an airbrush, so he deployed a multimedia technique on the model that would subsequently be applied to all of 2001’s spacecraft.

Using frisket masks—small pieces of plastic sheeting with adhesive on one side to protect areas from unwanted paint—he set about airbrushing sections of the fuselage, creating a nuanced, seemingly factory-assembled new exterior evidently composed of multiple joined metal panels with slightly different textures and shades. He also went to a hobby store in Borehamwood and started gluing small parts from plastic model kits in various places, augmenting the Moon Bus to create the effect of a meticulously engineered piece of technology. He scratched in fine lines, made new small panels, and constructed antennas. By the time he was done, 2001’s lunar transportation workhorse had become palpably flight ready.

• • •

Part of Gentleman’s mounting exasperation with Kubrick had to do with all the hairpin turns he kept making as he refined the film’s concept. Up until the end of August, Discovery’s destination was Jupiter. But by early September, the director had grown increasingly intrigued by Saturn—certainly the solar system’s most spectacular planet, but exceedingly difficult to represent convincingly on-screen. He was particularly provoked by the giant world’s symmetrical rings, which are made of innumerable fragments of ice.

One day Kubrick took a knife to Czech illustrator Luděk PeŠek’s large-format illustrated book The Moon and Planets, cutting out a four-page gatefold depicting a stream of ring fragments suspended in front of Saturn and pinning it to a bulletin board in his office. Kubrick imagined a giant monolith floating just beyond the outer rings, and that the rings themselves might have been made four million years ago, when the titanic forces that his extraterrestrials had deployed to produce the Star Gate had also shattered one of Saturn’s moons.

Most of those privy to the director’s new obsession hoped it would go away. They could foresee all kinds of difficulties in attempting to depict this complex planetary system. But on September 5 Kubrick was having dinner with a group that included Ordway, and asked his scientific advisor how he’d react if they substituted Saturn for Jupiter. Ordway replied that it might be a bit late to make such a change, but the director persisted, his advisor recalled, “pointing out the beauty of the Saturnian ring system and spectacular visual effect of Discovery’s traveling near or even through it.” Kubrick asked Ordway to write a document covering the visual aspects of Saturn—something duly produced after considerable research.

Despite initial objections from his effects staff, and in particular his small team of illustrators, Kubrick’s new twist served as the basis for many months of intensive work focusing on how to depict the Saturn system. It may have been the last straw for Gentleman, who on November 29 complained to a friend, “We are supposed to wind up this production by next September, but to arrange a reliable schedule in the face of continuing radical changes is going to be exceedingly difficult.” Years later, he expanded on his issues with the director. “My entire career, I had spent doing everything meticulously and precisely,” he said. “But when I ran into Kubrick, I found a man who had an absolute obsession with the finicky details of everything, and I wasn’t comfortable with that excess.”

I enjoyed Kubrick the man very much; the experience with him was vital and interesting. But I learned that one doesn’t work with Kubrick—one only works for him—and I found that rather difficult. As a filmmaker, he was a little paranoid and certainly obsessive. He surrounded himself with really good people and then proceeded to dissipate their talents. Eventually I got fed up with the sort of autocratic methods that were being applied, often seemingly arbitrarily and at variance to the useful application of the associated talent.

Visual effects assistant Brian Johnson provided his own insight into their rift. “If Stanley thought someone was slightly insecure, he could be quite a bully, and he bullied Wally Gentleman quite a lot; gave him a hard time,” he said. Gentleman, who was only thirty-nine at the time, had also been experiencing health complications, and by the end of the year had returned to Canada for treatment. (He lived to see the year 2001.) His loss was offset partially by the arrival of Con Pederson, who’d extricated himself, not without difficulty, from Graphic Films.

Discovery’s new destination pleased Clarke, however. While researching planetary geometries, he’d discovered that Jupiter and Saturn were destined to line up like billiard balls in the year 2001. Accordingly, he built a Jupiter flyby into his book draft, and Saturn became Discovery’s goal in the published novel.VIII

But after months of attempts to produce a realistic set of rings, Pederson and the film’s visual effects staff finally rebelled at the challenge of reproducing Saturn’s complex environment. They were only halfway through the live-action shooting of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and they simply faced too many other challenges. As Ordway remembered it, Kubrick reluctantly acceded to Jupiter’s return as Discovery’s destination following an “altercation” with them in mid-March 1966.

It was a rare example of the director backing down.

• • •

Kubrick had watched innumerable actors’ show reels throughout the summer and fall of 1965, and word had gotten around that Dr. Strangelove’s inscrutable mastermind was doing something Hollywood could understand: casting his next film. Rumor had it that Warren Beatty’s agent had been lobbying on his behalf for the lead role. If so, Kubrick had other ideas. By late September, the film was definitively cast. It didn’t include any “name” stars.

With Keir Dullea already slated to play Bowman, the director had met with Gary Lockwood weeks before sailing for London. A former college football star at UCLA who’d been expelled for brawling, Lockwood would play Dullea’s second-in-command, Frank Poole. In addition to carousing and getting into fights, the actor was a hard-core gambler, but he’d had the discipline to score various second-string roles on Broadway and in Hollywood films, and had also played the lead in a popular TV series, The Lieutenant. An impressive physical presence with a quick wit and an unlikely ability as a painter, he’d found employment as a film stuntman immediately after his ejection from college, even working briefly on Spartacus, though he’d never spoken to the director before. At their meeting, Kubrick told Lockwood he loved football, and asked why he thought the game was so popular. “I think it’s a combination of chess and violence,” was the response. The comment produced a great surprised belly laugh from the director.

Although surrounded in Elstree by some of Britain’s top actors, Kubrick wanted to stick with North Americans for his principals and had selected two for relatively significant roles. Robert Beatty, a Canadian who’d handled numerous parts on the London stage, would play lunar base commander Ralph Halvorsen. For Dr. Heywood Floyd, presidential science advisor and chairman of the National Council of Astronautics—a key role carrying the film’s middle section—Kubrick had chosen expat Californian William Sylvester, a regular presence on the London stage since shortly after World War II. Sylvester had played one of two leads in the BBC radio drama Shadow on the Sun, the production that had caught the director’s attention while he was shooting Lolita in 1961.

Other players of note included English actor Leonard Rossiter in the bit part of Russian scientist Dr. Andrei Smyslov—a role he’d play with such impressively oily unctuousness that Kubrick returned to him a decade later and cast him as Captain John Quin in Barry Lyndon. For Elena, another Russian scientist—and the only adult female in the film with more than a few lines—Kubrick selected accomplished stage actress Margaret Tyzack, whose prior London theater roles had included Lady Macbeth.

Although Kubrick’s UK company, Hawk Films, which he’d formed in 1963 for Dr. Strangelove, would announce most of these decisions in early January 1966, the director got steamed when MGM presumed to issue a press release in September announcing Dullea’s lead role. This prompted a heated cable to Caras on the twenty-fifth, in which the director demanded that his VP find out why the announcement hadn’t been left to Hawk. By now, Caras was in effect Kubrick’s ambassador to MGM, the core leadership of which was largely based not in Los Angeles but in New York, and specifically to its publicity department, whose US chief was Dan Terrell.

Another cable followed the next day after Kubrick had stewed some more. “It is most inappropriate for Bob O’Brien to make casting announcements, as it makes me seem like a contract director,” he complained. “Diplomatically tell this to Dan Terrell and ask for a policy agreement on this point. I, in turn, won’t make Otto Premingerish announcements about distribution.” (Preminger, a leading Hollywood director during the forties and fifties, was notorious among studio bosses for throwing his weight around.) The messages crystallized something of the ongoing transition from the old-school Hollywood way of doing things, in which hired-gun directors simply followed orders, and the emerging new paradigm of freelance directors and production companies making distribution deals with studios that granted them unprecedented levels of control.

Other personnel were being signed on as well, and on September 30 Victor Lyndon—a man well known in British film circles for his snazzy attire—informed Caras that Savile Row haute couture designer Hardy Amies was going to create the film’s costumes. Famous as the dressmaker to the Queen, Amies was something of a queen himself but, as acting head of the Special Operations Branch for Belgium during much of World War II, had acquired a reputation as a cold-blooded plotter of assassinations, responsible for numerous successful schemes to kill Nazis and their sympathizers.

Although not as celebrated as some other alliances between noted directors and clothiers—Yves Saint Laurent’s outfitting of Catherine Deneuve in Luis Buñuel’s Belle de Jour comes to mind—Amies and his design director, Ken Fleetwood, would play an important part in establishing 2001’s look. His simple, somewhat understated men’s costumes, which included slim-fitting suits with idiosyncratic details, were designed to look futuristic without inappropriately calling attention to themselves. His female attire—which included bubblegum-pink space station receptionists’ uniforms and cocoonish stewardess costumes with beehive shaped, shock-absorbing headgear—was a different matter.

“We were dealing with a period thirty-three years ahead in time,” Amies recalled in 1984. “To try and get a perspective on this, I looked back over the previous thirty-three years to see what had happened in the world of fashion. I realized to my surprise that there had been less change than one had imagined. I didn’t foresee, therefore, that clothing in the year 2001 would be dramatically futuristic. Mr. Kubrick accepted this.”

Set decorator Bob Cartwright, who’d joined Masters and Kubrick in New York and was now working at Borehamwood, attended a production meeting with the director in which future trends in clothing and other potential social transformations were discussed. “I was skeptical about the major changes they were implying would have happened to ordinary people and ordinary life,” he remembered. “I said that my daughter was very keen on animals. I was sure in 2001 when she’s forty-six that she would have a daughter that also would have pets, and those things won’t change.” Cartwright believed the scene in which Heywood Floyd calls his young daughter from Earth orbit and discovers that she wants a pet for her birthday probably originated from his observation.

• • •

On September 10 Clarke visited Borehamwood and “emerged stunned,” he wrote Wilson, then in final preproduction for his James Bond parody in Colombo. Stage 3, the biggest at the studio, was now dominated by a smoothly curving, 150-foot-long, 30-foot-wide structure floating under rigging suspended on chains from ceiling beams five stories above. Containing catwalks and innumerable rows of 1000-watt Fresnel lights, all pointing downward at diffusion gels set in the space station’s ceiling, this nest-like pipework service structure matched the smooth curvature of the set below.

Clarke drew a diagram of it and compared it to a ski jump: “Actors at the far end will have to learn to walk tilted.” It wasn’t even a vital scene, he observed: “This is no longer a $5,000,000 movie. I think the accounts department has thrown up its hands; the guess I heard was $10,000,000.”

Seen with all lights blazing, the visual impact of the set’s exterior was indeed powerful. Visitors were permitted entry from the side and would then find themselves within a brilliantly lit rim section of an ostensibly wheel-shaped space station 750 feet in diameter. A strange phenomenon began to manifest itself as they approached either end. Although the furniture and walls indicated that gravity should pull thisaway—namely, in the direction that all visible cues indicated it should—in practice, it pulled thataway: toward the invisible studio floor. While this optical-versus-gravitational illusionism was somewhat tolerable when walking at an increasing tilt toward either end of the curve, visitors inevitably experienced an unsettling vertigo upon turning around. The perspective switch was too much, and a spinning sensation kicked in. With the trickster floor now sloped nauseatingly away, many had to sit down rapidly to avoid falling.

“In about six weeks, things should be very exciting,” Clarke continued. “Shooting now set to December 1. Release slipped to Mar ’67, tho’ Stan still talks ’66 . . . Unfortunately he has no time to finish the script (!!!) so can’t finalize the novel. So I can’t sell it, while Scott chews his fingernails. Never mind.”

Shooting would slip further than that, and Scott Meredith’s nails would suffer for much longer than either of them suspected.

• • •

In key ways, Clarke’s futurism had been formed by that comment made by Russian spaceflight visionary Konstantin Tsiolkovsky—the one he’d quoted in his short story “Out of the Cradle, Endlessly Orbiting”: “Earth is the cradle of the mind, but humanity can’t remain in its cradle forever.” The thought was contained in an essay the rocket scientist had published in 1912, five years before the Russian Revolution and less than a decade after the Wright brothers lifted their plane above the Kitty Hawk sand. In a sentence, Tsiolkovsky had laid out the ideological foundations for spaceflight. Even more than the work of British science fiction writer Olaf Stapledon, the pronouncement had influenced Clarke’s worldview, in which Earth was but a stepping-stone to the cosmos.

His most influential novel, Childhood’s End, was named in oblique reference to Tsiolkovsky’s concept. In the book, a final recognizably human generation loses touch with its children, who begin to display signs of group clairvoyance and telekinetic powers. Under the supervision of a powerful alien master race, the Overlords, Earth’s children merge into a single group consciousness comprising hundreds of millions of individual minds.IX “To all outward appearances, she was still a baby,” Clarke wrote of one of the children, “but round her now was a sense of latent power so terrifying that Jean could no longer bear to enter the nursery.”

With production looming, pressure was building to finalize important aspects of the story, including, of course, the ending. Ideas continued emerging in a steady stream from both writer and director. “Stanley phoned with another ending,” Clarke noted on October 1. “I find I left his treatment at his house last night—unconscious rejection?” He retreated to his apartment on the top floor of his brother’s house, not far from Borehamwood, and began drafting alternate conclusions to 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Their current final sequence relied heavily on voice-over. According to an omniscient narrator, the extraterrestrials had undergone an evolutionary transition of their own since decisively influencing prehistoric humanity four million years before—transitioning through an “age of . . . Machine Entities” and learning how to “preserve their thoughts for eternity in frozen lattices of light.” Freed from “the tyranny of matter,” they were now “Lords of the galaxy . . . But despite their godlike powers, they still watched over the experiment their ancestors had started many generations ago.” On the final page, Bowman was supposed to be seen flying his pod toward a “great machine” in orbit of Saturn (or presumably Jupiter, when they reverted to that destination). What happened next was frustratingly opaque, however, and the narrator’s final words didn’t help much: “In a moment of time, too short to be measured, space turned and twisted upon itself.”

Within a few days, the author had produced a selection of new endings, and on October 3 Kubrick called to fret about the existing one. It wasn’t clear what it was supposed to mean. It was simply too inconclusive. Clarke went through the alternatives he’d been working on, and one “suddenly clicked: Bowman will regress to infancy, and we’ll see him at the end as a baby in orbit. Stanley called again later, still very enthusiastic. Hope this isn’t false optimism: I feel cautiously encouraged myself.”

Kubrick’s approval was likely rooted in his own appreciation of Tsiolkovsky’s formulation,X which he cited only a few weeks later in a draft response to a question from the New York Herald Tribune. Clarke’s new ending may have been prompted by two other factors as well. One was an illustration reproduced in Robert Ardrey’s African Genesis, the book already so influential to the film’s prelude. A small pen-and-ink rendering, it depicted a fetus floating in a bubble-like amniotic sac, surrounded by other featureless bubbles in a kind of pointillist void composed of black dots. It looked exactly like an unborn baby in space.

A second influence—certainly regarding Kubrick’s receptivity to the idea—was Swedish photographer Lennart Nilsson’s stunning color photographs of human embryos, which had appeared just a few months before in Life. As with the illustration, the cover of the magazine’s April 30, 1965, issue depicted a fetus seemingly floating in cosmic darkness—ostensibly the inner space of the womb, though, in fact, all but one of Nilsson’s pictures were of embryos that “had been surgically removed, for a variety of medical reasons,” as the text explained. Nilsson’s work caused a worldwide sensation and definitely caught the director’s attention.

For a while, 2001’s Star Child was supposed to detonate orbiting nuclear weapons in Earth orbit—a scene that remained in the novel but not the film, where it was judged too similar to Dr. Strangelove’s ending. In any case, after so many failed attempts, Clarke himself initially appeared less than certain of his new idea. But a few days later, he wrote, “Back to brood over the novel. Suddenly (I think) found a logical reason why Bowman should appear at the end as a baby. It’s his image of himself at this stage of his development. And perhaps the Cosmic Consciousness has a sense of humor. Phoned these ideas to Stan, who wasn’t too impressed, but I’m happy now.”

Whatever Kubrick may have thought of Clarke’s post festum rationale, his initial enthusiasm held. They had their ending.

• • •

Kubrick’s management methodology was simultaneously egalitarian and hierarchical. He was the boss, of course, but his door was always open to his closer collaborators regardless of their ostensible rank. Particularly when he felt comfortable with someone, he used that person as a sounding board at all hours of the day or night, seeking his opinion (and it was almost always a he) on matters well outside his official role. He was a good-humored presence, by and large, and in particular liked to banter with his younger assistants about their extracurricular activities, sometimes with prurient curiosity as the sexual revolution unfolded in Swinging London, directly down the new M1 Motorway from Borehamwood.

Still, he wasn’t always happy when one of his subordinates piped up with unsolicited opinions or when he perceived that his more junior employees were freelancing in areas outside of their assigned domain—particularly if this hadn’t been taken under his own initiative.

For his part, Doug Trumbull was feeling increasingly confident. Lately, he’d been experimenting with creating large slices of lunar topography and had devised an effective way of hosing down his large Moon surface model with water, climbing to a high catwalk, and dropping various-sized stones on it, thus producing convincing craters in the wet clay. He’d received unstinting support in all this and had already been invited to the director’s home for dinner. (Although Kubrick would ultimately elect to use a more jagged landscape, Trumbull’s softly rolling terrain proved closer to what Apollo astronauts actually saw when they started flying to the Moon in 1968.)