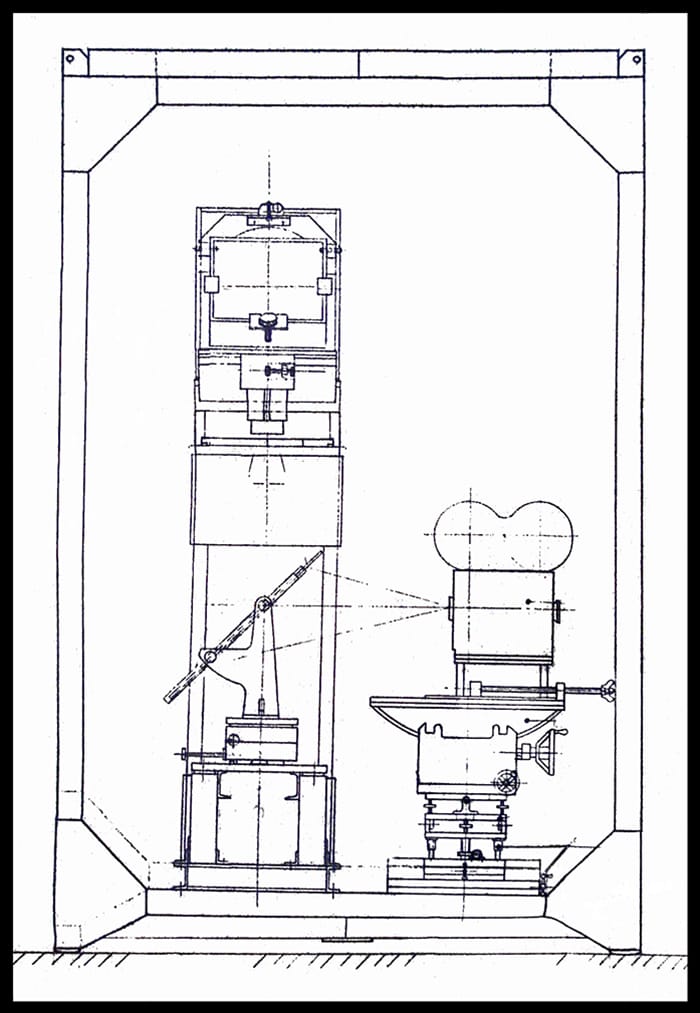

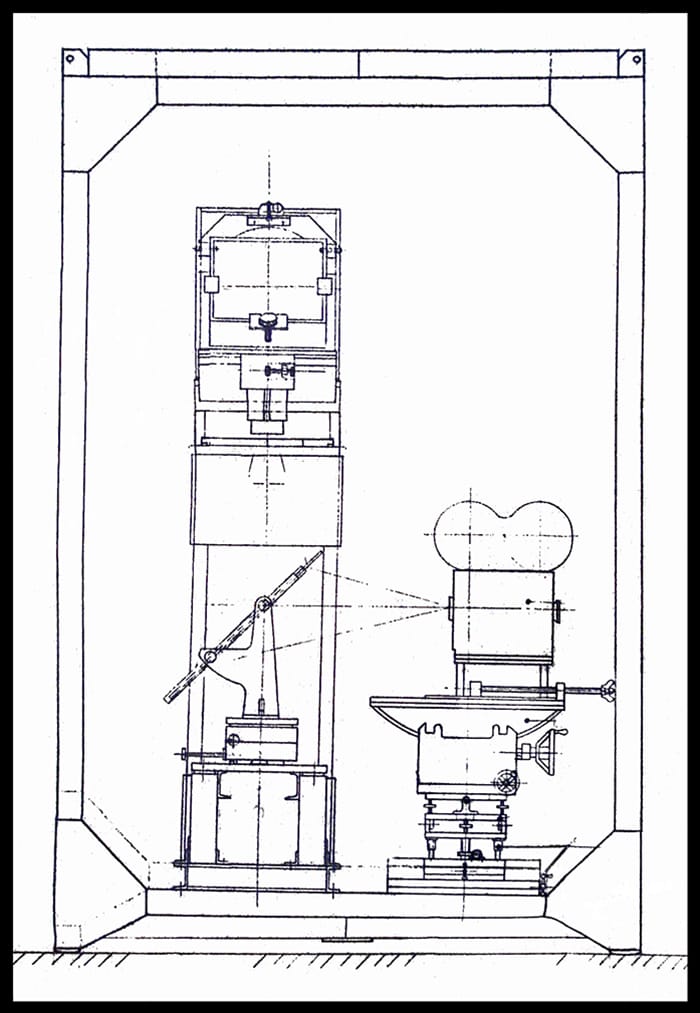

Dawn of Man front-projection rig, with camera to the right and projector suspended vertically to the left above an angled mirror.

WINTER 1966–FALL 1967

No individual exists forever; why should we expect our species to be immortal? Man, said Nietzsche, is a rope stretched between the animal and the superhuman—a rope across the abyss. That will be a noble purpose to have served.

—ARTHUR C. CLARKE

Stuart Freeborn was facing a problem the likes of which he hadn’t encountered in his entire thirty-year career. He’d done many innovative and even extraordinary things in that time. Most recently, he’d helped divide Peter Sellers into three readily distinguishable characters in Dr. Strangelove, including an earnestly balding President Muffley and the film’s namesake, a megalomaniacal wheelchair-bound Nazi rocket scientist with a bad case of phantom limb disorder. Two decades previously, in a kind of inverse cosmetic surgery, he’d affixed a convincing pot belly on an otherwise slim Roger Livesey, whom he’d also morphed into believable late middle age in Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1943 film The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp—something that would have been relatively easy were it not for the fact that Livesey wore only a bath towel throughout one extended scene.

Most notoriously, he’d created the prosthetic schnozzle that had transformed Alec Guinness into Fagin in David Lean’s 1948 version of Oliver Twist—a hooked beak so extravagantly anti-Semitic that it wouldn’t have looked out of place in Der Stürmer, the notorious Nazi tabloid, though it was actually based on George Cruikshank’s illustrations from the Charles Dickens book’s first edition. (Half Jewish himself, Freeborn had suggested to the director that it might cause offense—but Lean overruled him.)

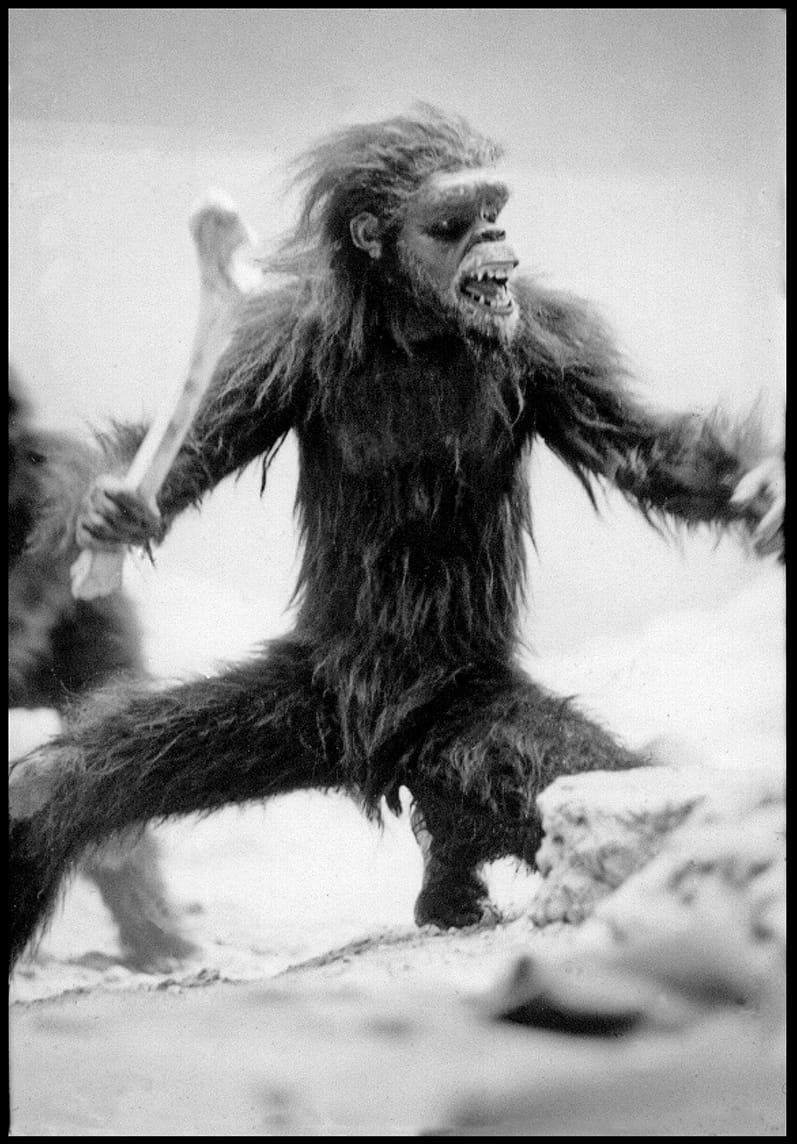

By the time a skinny, moustachioed kid named Dan Richter showed up in his studio at the end of October 1966, Freeborn had already tried an ape-man suit (which Kubrick had found artificial and wanting), produced a small posse of believable but freakishly neutered Afro-British Neanderthals (which since they really needed to be able to go forth, procreate, and inherit the Earth, also failed to fit the bill), and when Dan knocked on his door on a Monday morning, he’d been working for weeks on an expertly crafted new man-ape costume that he was quite proud of. Freeborn picked up the mask and showed it to Richter—who seemed an intelligent sort, albeit evidently from some kind of countercultural fringe. “What do you think?” he asked.

For his part, Richter had been impressed by Freeborn’s studio, with its skylight, makeup chairs, and worktables crammed with various plaster, wire, and urethane forms. Clearly this was a place of transformation. People came in looking one way, and left looking entirely different. As for Freeborn, Dan thought to himself, “He looks like a character out of Beatrix Potter”: balding, bespectacled, high strung but not necessarily nervous; an alert, energized creative force with a bit of leprechaun in his veins.

But as he examined the mask, he knew immediately it wouldn’t work, though it had clearly been made with a great deal of care. He didn’t want to hurt Freeborn’s feelings and was acutely conscious that he was in the workshop of a master. And yet the mask was simply too thick. “It’s just useless for what I’m trying to do,” he thought. “He’s a brilliant artist. But it’s not what I want to do.” He decided to be up front.

“Well, you know, I have a little bit of a problem with this, Stuart,” he said. “This is really beautiful. The thing is, wearing a mask like that would be like . . . a bag over my head. I couldn’t express myself.”

The performer quickly tried to explain that he was hoping to wear as little costume as possible. He would be seeking to convey acting values. For him, masks and costumes were barriers to be overcome. Accepting these thoughts with a nervous laugh, Freeborn showed him the suit that went with the mask. To Dan, it seemed like an inordinately thick second skin, and much too heavy. “I can’t do this,” he said. “I just can’t do this. Our characters have to show through. Whatever you create for us, it can’t just be a surface that covers us. It has to enhance who we are and what we feel.”

Although Dan could see him covertly fighting annoyance and disappointment, Freeborn took it well, and as they continued to talk, he seemed to understand that Richter was seeking as thin a layer as possible between performer and camera. Rather than making something apelike and then putting a man inside, he would need to build something up from a man’s body. He suggested that Dan come back as soon as possible for a full-body cast.

Remembering that first meeting decades later, Richter commented, “Here’s this American kid, obviously a dopey, who comes in to one of the great makeup artists of British film—The Bridge on the River Kwai, a major guy—and says, ‘None of this will work.’ At first, he thought, ‘Who the fuck is this guy?’ He’s very polite, very English, he’s very polite and everything. And I’m sure he must have gone to Stanley and said, ‘What’s going on?’ And Stanley said, ‘No. You guys have to work together; Dan’s onto something here.’ ”

• • •

At its best, science fiction takes our post-Enlightenment way of understanding the world and extrapolates, using the findings of science and projections concerning the future of technology and putting them at the service of truths expressible through fiction. By the midsixties, astronomy and astrophysics had radically expanded the universe’s dimensions, and the emerging science of paleoanthropology—a discipline rooted in Darwinism, paleontology, and biological anthropology—was starting to revolutionize our understanding of human origins. But rarely had the findings of these broad disciplines been incorporated into artistic expression. Instead, science had effectively been over here, and the arts elsewhere.

It was one of Kubrick’s and Clarke’s great achievements, and a wellspring of 2001’s lasting power and continuing significance, that they took the complex, sometimes haunting, sometimes magnificent truths revealed by modern science, polished them with all the care given an expensive piece of Zeiss glass, and used them as a window to view the human condition within a staggeringly vast universe. Projecting back into the past, 2001’s authors examined human origins. They weren’t particularly doctrinaire about it. This was fiction, not a peer-reviewed paper in the journal Nature. But they always deployed scientific research—and its miraculous offspring, technology—to define their story, refine it, and expand it to its farthest possible limits. It’s how they reached the border between the known and unknown—that place science is always probing like a tongue exploring a broken tooth. It’s where they wanted to take their audience, because beyond it, something like magic prevails.

As with other players in his production, Kubrick’s direction of Richter involved providing him with tools, suggestions, responsibilities, and the freedom to explore. He signaled his serious intent by handing him hard-core research papers by paleoanthropologists, popular science books by Robert Ardrey and Desmond Morris, and invitations to highbrow London seminars with titles such as “Kinship and the Family in Primates and Early Man.”

The director also pointed him in the direction of the Regent’s Park Zoo monkey house, and informed Richter that, by the way, he now had responsibility for Hawk Films’s own small menagerie, which had been either leased or bought outright back in July for 2001’s prehistoric prelude. Then under the care of Jimmy Chipperfield’s Circus, Kubrick’s ark included a leopard, two hyenas, two vultures, two peccaries, two large snakes, three zebras, and twelve tapirs—the latter a large South American herbivore with a prehensile trunk destined to serve as Moonwatcher’s first kill, and never mind that the species was foreign to Africa.

In retrospect, one of Kubrick’s most important moves was simply to give Richter a beautiful 16-millimeter Beaulieu film camera, arrange instruction on how to use it, and provide unlimited stock and processing. Richter also received a projector fresh from the disassembled centrifuge, and with that, the director had provided his incipient man-ape with filmmaking’s two most important tools, channeling him to think not only as performer but also as participant in the cinematic process. Concluding a soliloquy on the merits of the Beaulieu, Kubrick said, “Now just go out and do all the research you want. Just collect information, and then we’ll make decisions.”

One of Richter’s later stops was a visit to illustrator Maurice Wilson at London’s cathedral-sized Natural History Museum. Wilson’s exquisite full-color renditions of wildlife rivaled James Audubon’s in their vivid detail and beauty. For several years, he’d been examining the museum’s fossil fragments of early man and producing paintings reconstructing what Australopithecus and other protohuman species may have looked like, and how they might have behaved. By the time Richter got to Wilson the mime had been researching for more than a month, and he was growing increasingly frustrated to learn how little we truly knew about our earliest ancestors.

In Wilson, however, he found an artist who’d already gone through exactly the same process, and who was willing to share what he’d gleaned. The Australopithecus specimens that Raymond Dart had uncovered were indicative of small creatures: no more than four and a half feet tall and very slender. The scientific thinking at that time was that they probably weren’t yet bipedal, though this has since been revised upward in favor of bipedalism. In Kubrick’s and Clarke’s conception, 2001’s mysteriously powerful alien artifact was supposed to suggest not just tool use but also foster an upright stance. In choosing Australopithecus africanus and setting their prelude four million years ago, they had fortuitously arrived at exactly the right species and time frame.

Wilson also provided Richter with a visceral opportunity to convert the dry words of the scientific papers he’d been reading into something far more tangible. Taking him behind the glass-fronted display cases of the public museum into a hidden network of research labs and storage areas, he brought him to a spacious room lined with shelves and cabinets.

He comes to a stop by a large Victorian wooden cabinet. As he opens it I see that it is filled with pieces of bones and skulls as well as casts from other collections. There is a smell of great age in these dusty corridors that seems to add authenticity to the moment. Mr. Wilson lets me hold models and bits of original bones of Australopithecus. I feel a taste in the back of my mouth, and my heart races. I have made contact. Holding a skull that Professor Dart cast from the real fossils of a young boy is stunning. I can feel the ridges and pockets of its surface. There are two holes from the canine teeth of a leopard, which may have been the cause of his death.

Returning after such revelations to Borehamwood, Richter invariably discovered that Kubrick had been working the problem just as hard. “He’d be, ‘Hey Dan, you got a cigarette?’ Because Christiane wouldn’t let him smoke,” the performer recalled. “I’d give him a cigarette. He’d say, ‘Listen, you know I was seeing this thing Desmond wrote.’ ‘Wilson wrote this.’ Or: ‘Hey, have you seen the Jane Goodall footage that Hugo van Lawick shot?’ You know, ‘Victor called up some people, we got National Geographic, they said they can give us some outtakes.’ It was like gold, this stuff.”I

Apart from the museum, Richter repeatedly visited a mournful, thoughtful London resident, Guy the Gorilla, at the Regent’s Park Zoo. Throughout the winter of 1966–67, he spent so much time with the twenty-two-year-old silverback that Guy started to acknowledge his presence “with a calm look. He looks through ordinary zoo visitors, but if I move around in front of his cage, his eyes follow me.” Bringing along his Beaulieu, Dan observed that though the gorilla had a limited range of movement due to the small size of his cage (“I can’t help feeling that Guy is like an innocent man in jail for something he has not done, with no idea of what he has been charged with”), when he did move, he had a way of shifting his weight directly from the center of his massive body. Richter started experimenting with his own body language.

What great control! I reach for something, the movement begins in the very center of my body. I stand up, turn, and run—all the movement starts from my center. Moving this way does many things. It immediately removes the humanness from my movements. It creates size—suddenly I’m bigger, weightier. Animals move with their whole bodies. Try moving this way. It creates energy and power. Guy gives me this. He gives Moonwatcher size and dimension . . . Thank you, Guy, old friend.

• • •

Kubrick’s alternate plan for shooting the Dawn of Man was to use a technique then fairly new to feature filmmaking called front projection. Throughout Birkin’s search for a usable desert landscape in the United Kingdom, front projection was probably more a plan A than a plan B in the director’s mind—though the concept was closely held. He simply didn’t want to go far from the controlled setting of Borehamwood, to say nothing of the comforts of home, but he wasn’t entirely sure that front projection would work. So he enlisted help from the Academy Award–winning head of visual effects at MGM’s British studios, Tom Howard, and quietly set about doing camera tests with John Alcott.

Previous to 2001, many films used rear projection as a special effects technique. The classic example is the couple in the car with the road rolling back toward the horizon behind them. Rear projection was also used extensively in 2001 to provide a convincing simulation of high-resolution flat-panel electronic screens in the spacecraft sets. But the problem with rear projection when using bigger screens—screens big enough to put a car, or an entire desert landscape set, in front of—is that the projected image has to fight its way through the screen material rather than bounce off of it. This reduces both brightness and sharpness. Although Kubrick had used rear projection extensively in Lolita and Dr. Strangelove—notably when actor and rodeo star Slim Pickens, as Major T. J. “King” Kong, rode his H-bomb down to a terminal encounter with Mother Russia—he was keenly aware that its inherent artificiality wouldn’t work in 2001.

In 1964 Kubrick had methodically watched all the films produced by the Japanese production company Toho, the studio behind the Godzilla franchise, among other sci-fi offerings of the 1950s and early 1960s. He almost certainly saw its 1963 film Matango, about a group of Sunday sailors who lose their yacht in a storm and take refuge on a mysterious island, where they mutate into grotesque shiitake people after eating the local mushrooms. While the horror component wasn’t particularly well handled, director Ishirō Honda pioneered the use of front projection for maritime scenes on the yacht. These were several orders of magnitude more realistic than anything achievable with rear projection, and Kubrick would certainly have taken note of this.

Front projection relied on a highly reflective material, Scotchlite, that was invented by the 3M company in 1949 and subsequently used in reflective road signs. The material contained millions of tiny glass beads, which reflected light back at the source with incredible efficiency. A Scotchlite front-projection screen was hundreds of times more efficient at bouncing a projector’s light back to a camera’s lens than rear projection, and because it reflected from the front, soft focus was less of a problem. There were certain limitations, however. Because all those glass beads reflected light in a narrow beam back to its source, the camera had to be aligned exactly with the projector lens—a seeming impossibility, given that both projector and camera were bulky pieces of equipment and couldn’t possibly be in the same place at the same time.

The front-projection process developed by 3M researcher Philip Palmquist solved this problem by placing a two-way mirror in front of the camera lens, angled at 45 degrees. Positioned at 90 degrees from the camera was the projector, which cast its beam on the mirror, which, in turn, reflected it onto the Scotchlite front-projection screen, such that the light bounced back directly at the camera behind the mirror. While the projected image also fell across the actors in the foreground—say, a man-ape with a bone in his hand—it was far too faint to be seen on anything or anyone not draped in Scotchlite. And just as Bill Weston’s body hid the cables used to suspend him on Stage 4, producing a near-perfect simulation of weightlessness, in practice the shadows cast by performers on the screen from the projector’s beam were hidden from the camera by their own bodies.

Dawn of Man front-projection rig, with camera to the right and projector suspended vertically to the left above an angled mirror.

There were other drawbacks, however. The camera either had to remain fixed or bring the projector and mirror system along with it wherever it went—a cumbersome proposition. And the lighting and color temperature of the foreground set had to be tweaked so as to ensure that the set and its performers merged seamlessly with the projected background image; otherwise the illusion that the actors were playing their roles within the wider frame of the image collapsed. But with Howard and Alcott working the problem, Kubrick was confident these issues could be overcome.

• • •

Among the locations that Kubrick had sent scouts to photograph was South West Africa—today’s Namibia—as well as neighboring Botswana, collectively a vast desert expanse defined to the east by the Kalahari Desert and bordered on the west by the Skeleton Coast, so called because the absence of fresh water for hundreds of miles gave shipwreck survivors the reliable prospect of a long, slow, agonizing death. In 1966 South West Africa was still ruled by South Africa, and thus subject to the strict racial segregation of apartheid.

Of all the locations Kubrick had seen pictures of, the Kalahari and the Namib seemed to provide the most variety and possibility. These ocher deserts also had the advantage of absolute sun-baked legitimacy as a central stage for early man’s struggles. Having abandoned the idea of filming his man-apes on location—a decision that compounded his reluctance to leave the studio’s controlled environment with the impracticalities of shooting supposedly parched desert exteriors in the iffy British weather—Kubrick decided to pull together a small production team and send it to the region to capture realistic backdrop stills. Because of the resolution of the 65-millimeter film frame, the landscapes would have to be photographed as large-format eight-by-ten-inch fine-grained positive transparencies.

Prior to leaving the production, Tony Masters had suggested that his assistant Ernie Archer, who would be elevated to full production designer upon his departure, should be sent to Africa as well. That way he could ensure the backdrop photographs were framed such that the foreground sets he’d be designing and constructing would match. Masters’s idea came during a meeting in which all three were present, and though Kubrick immediately agreed, he suddenly looked concerned. “How will I know what you’re looking at, Ernie?” he asked. “I mean, how will I be able to tell if you’re shooting the right thing?”

This hadn’t occurred to Archer, who replied, “I don’t know, Stanley. You can’t, really. Just leave it to me.”

Never one to accept an easy out, Kubrick was having none of it. “Oh, no, God no,” he said. “I’m not going to know what you’re doing.” Thinking it over, suddenly the director grew enthusiastic. “I’ll tell you what. Here’s what we do: no matter how far out in the wilds you are, there’s always a village with some drums or something, and you can send a message back to the capital, where they have phones. What you do is, you have a piece of glass on the back of your camera with graph lines ‘A-B-C’ across the top, and ‘1-2-3’ down the side, and you draw the scene you’re looking at and call it over to me: A-3, B-9, and so on. I’ll be in the office back here in England with my graph, and I’ll be drawing it too. Then I can look at it and tell you: ‘Yes, that’s great. But Ernie . . . three feet to the left.’ ”

At this, Archer shot an amused glance at Masters. “Stanley, it’s never going to work, you know,” he said. “You can’t do something like that!” And they all laughed. Remembering the conversation, Masters commented, “It was madness—but out of madness came a lot of very good ideas, too.” In fact, however impractical it may have been at the time, Kubrick had hit upon much the same method that would be used years later when transmitting digital pictures across great distances—or even simply copying them from one hard drive to another. Minus the drums.

In January Kubrick summoned Birkin and instructed him to gear up for another scouting expedition, this time to landscapes not readily accessible from Euston station. He’d already hired Pierre Boulat, a French photographer who’d worked for Life magazine. Boulat would be flying into South Africa with an assistant the second week of February. Kubrick asked Birkin to book a ticket to Johannesburg, proceed to Windhoek, the capital of South West Africa, hire a safari expedition, meet Boulat and Ernie Archer, and make the long desert drive to the Spitzkoppe hills—an ancient granite formation rising abruptly from the otherwise flat central Namib. All of Boulat’s shots would have to be taken at dusk or dawn, which should allow Birkin plenty of time to scout other locations by Land Rover or light aircraft. Go arrange the thing with Victor, said Kubrick. Mind your expenses, bring plenty of Polaroid film, watch your back, and report back frequently.

Birkin, who’d recently broken up with Hayley Mills, welcomed the chance to fly into summer. He wasn’t prepared to leave his sense of morality behind, however, and his African experience got off to a rocky start. Arriving at Jan Smuts Airport via South African Airways DC-7 on February 1, 1967, he got to a blank in the customs form where he was supposed to specify his race and wrote “human” inside—a nice allusion to the Dawn of Man, possibly, but not particularly amusing to the border police. Compounding this, when they searched his bags, they discovered a contraband copy of Playboy as well. Confiscating the magazine (“for their own use,” Birkin assumed), they took him into a “sort of locker room,” ordered him to drop his trousers, and subjected him to what’s known euphemistically as a “full-body cavity search”—though Birkin recalls the incident in more direct terms.

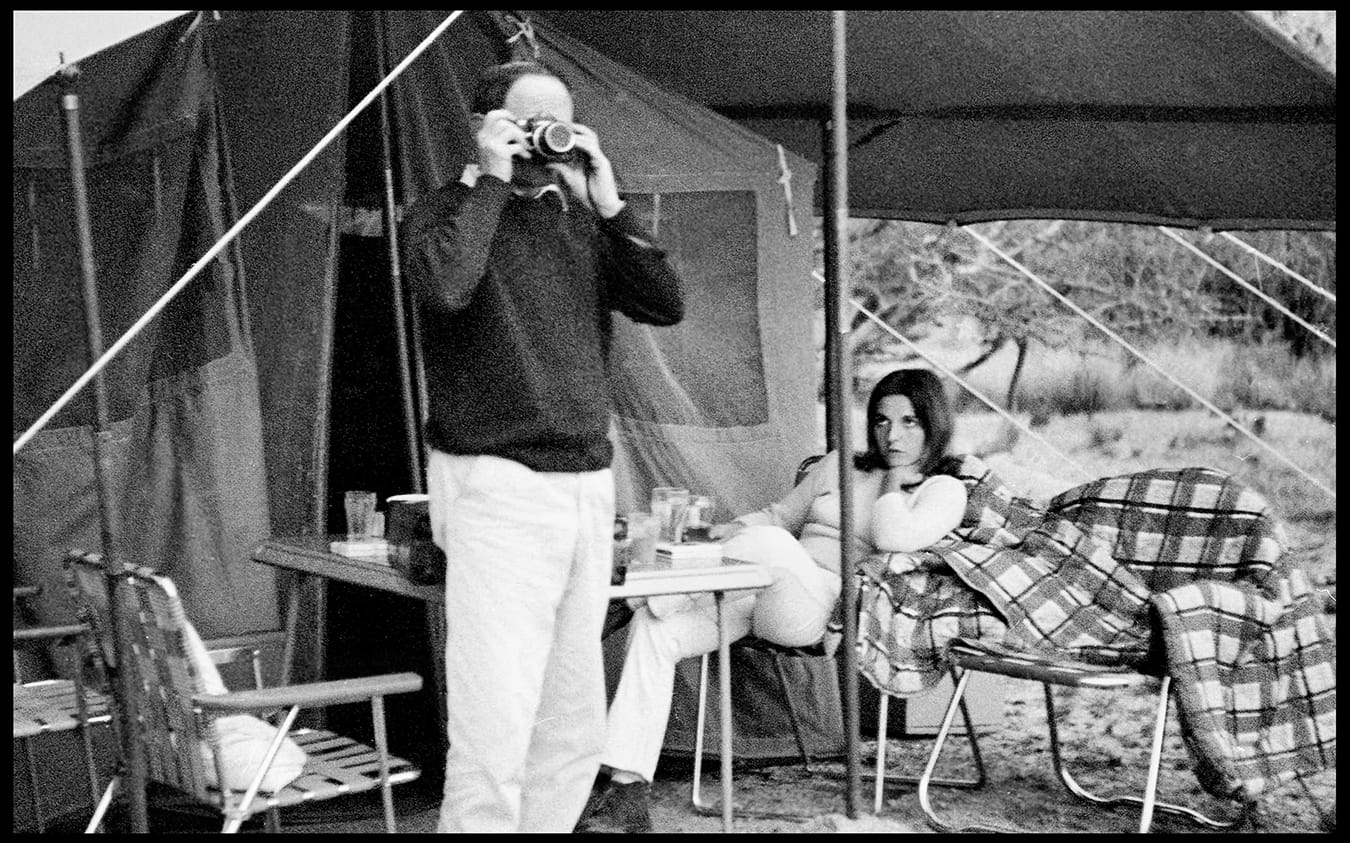

When he’d recovered from this South African welcome, he opened a bank account in his own name—neither Hawk Films nor MGM was allowed to do so because of British apartheid restrictions—extracted a dangerously large amount of cash, stuffed it into his suitcase, and flew on to Windhoek, where he was met a few days later by Archer. Together they purchased a pair of Land Rovers, hired safari organizer Basie Maartens, and arranged for a small plane to serve as a shuttle and location-scouting service. It would fly exposed film directly from the desert to Windhoek, where it could be airfreighted on to London. Then on February 7, “I go to meet the airplane for Pierre Boulat,” Birkin recalled. “Somewhat to my dismay, because I thought I had a broken heart at that point, his assistant is wearing a miniskirt. She was about twenty-one, my age. So there was a fairly immediate, Uh-huh.” Her name was Catherine Gire.

Rumbling up to the Spitzkoppe hills in a multi-vehicle expedition kitted out in the style expected by the Texas millionaires who usually hired it for big-game hunting—fourteen tents, including one large enough for a grand dining room straight out of Lawrence of Arabia—they discovered a rugged bronze landscape of jumbled boulders and smoothly serpentine outcroppings. They’d arrived at one of the chief backdrops of 2001’s Dawn of Man sequence. Returning by light aircraft to Windhoek after a week to get supplies, Birkin wrote his father.

We’ve been in tents for over a week now, and in spite of the fleas, bugs, mosquitoes, horned-beetles etc, etc that invade one’s sleeping bag every night, I love it. The country is as wild and desolate as you can imagine—the hills where we are, Spitzkoppe, consist of huge rounded boulders rising out of the scrub. Every morning at 5 AM we go off and wait for the dawn to creep over the horizon. And again at dusk. After the rains there are the most beautiful sunsets I’ve ever seen—very strange pinks and indigos throwing shadows for miles into the desert . . . I sent the first batch of photographs off to England this morning. The photographer is shaking with fear that Stanley will ring up and have him recalled.

Boulat, who couldn’t see his own results, needn’t have worried. His first batch of exposed Ektachromes already contained the evocative sunrise and sunset images that Kubrick would use as his film’s opening shots, including the Dawn of Man title card picture. As they moved between locations, however, Boulat’s agitation only increased, now due to clear signs that his assistant, who’d evidently been brought along not entirely for her photographic skills, was focused not on him but on Birkin. For his part, when he wasn’t chatting up Catherine during the long days, Birkin would drive off in a Land Rover scouting new locations, or sometimes sit in the shade with a typewriter and pound out a draft of a screenplay he was writing based on Thomas Hardy’s novel Jude the Obscure.

At night, they convened in the dining tent, where they were served by the six local men brought along to do the grunt work, all of whom lived in a single tent. Basie Maartens’s safari workers subsisted on grain mash—something akin to animal feed—while the Europeans dined on steaks and drank fine South African Cabernet. “We’ve all talked and argued about apartheid,” Birkin wrote his father. “When I was making up the food list for the safari, Maartens, our guide, said, ‘Just get 10 pounds of pump nickel for the n . . . . ers, that’ll last them 2 months.’ ” After dinner, the group gathered around the campfire, where swarms of multicolored butterflies and moths appeared out of the desert darkness and hurled themselves into the flames—apparently, Birkin surmised, because they’d never seen fire before. A pair of thrumming gas-powered generators provided electricity to a refrigerator packed with film, and a record player, which Birkin used to play Shostakovich and the Stones under the stars.

Although the Central Namib usually contained no carnivores big enough to present a serious danger, highly venomous small scorpions emerged from the rocks at night. Catherine Gire “was the unfortunate finder of the first scorpion—in the loo!” Birkin wrote his father. “There she was, helpless, screaming into the night air.” She hadn’t been stung, however, only scared. Not long after, it was Birkin’s turn. After washing in one of the shower tents, he unthinkingly sank his face into a towel—and received a sting like a high-intensity bolt of electricity to the nose. Screaming in agony and pawing at himself, he had to be held down by two workers while Maartens shouted that it was for his own good—without restraint, he’d likely do himself serious damage. “The pain is so intense, you try to tear your face off,” Birkin recalled.

Pierre Boulat and Catherine Gire.

In the mornings and evenings, Maartens’s laborers helped them haul camera equipment to the positions Kubrick had identified in Archer’s and Birkin’s Polaroids, which had been airlifted to London. A chain gang then passed unexposed film extricated from the fridge up the line from their campground to the boxy Sinar camera, which Boulat operated by sticking his head under an old-fashioned black hood—but not before checking it for scorpions. Freshly exposed film was returned in the same way. After bedtime, Catherine would sneak into Andrew’s tent or vice versa. “She told me he’d taken her out as his assistant, and she made it conditional, that was strictly where her occupation ended,” said Birkin. “So she could see nothing to bar the two of us having a bit of fun.” They kept the arrangement as quiet as possible under the circumstances, until one night Pierre “came into our tent at like five o’clock in the morning, screaming with rage, not so much at me, but at her. Everyone’s naked running tangled in the middle of the Kalahari Desert.”

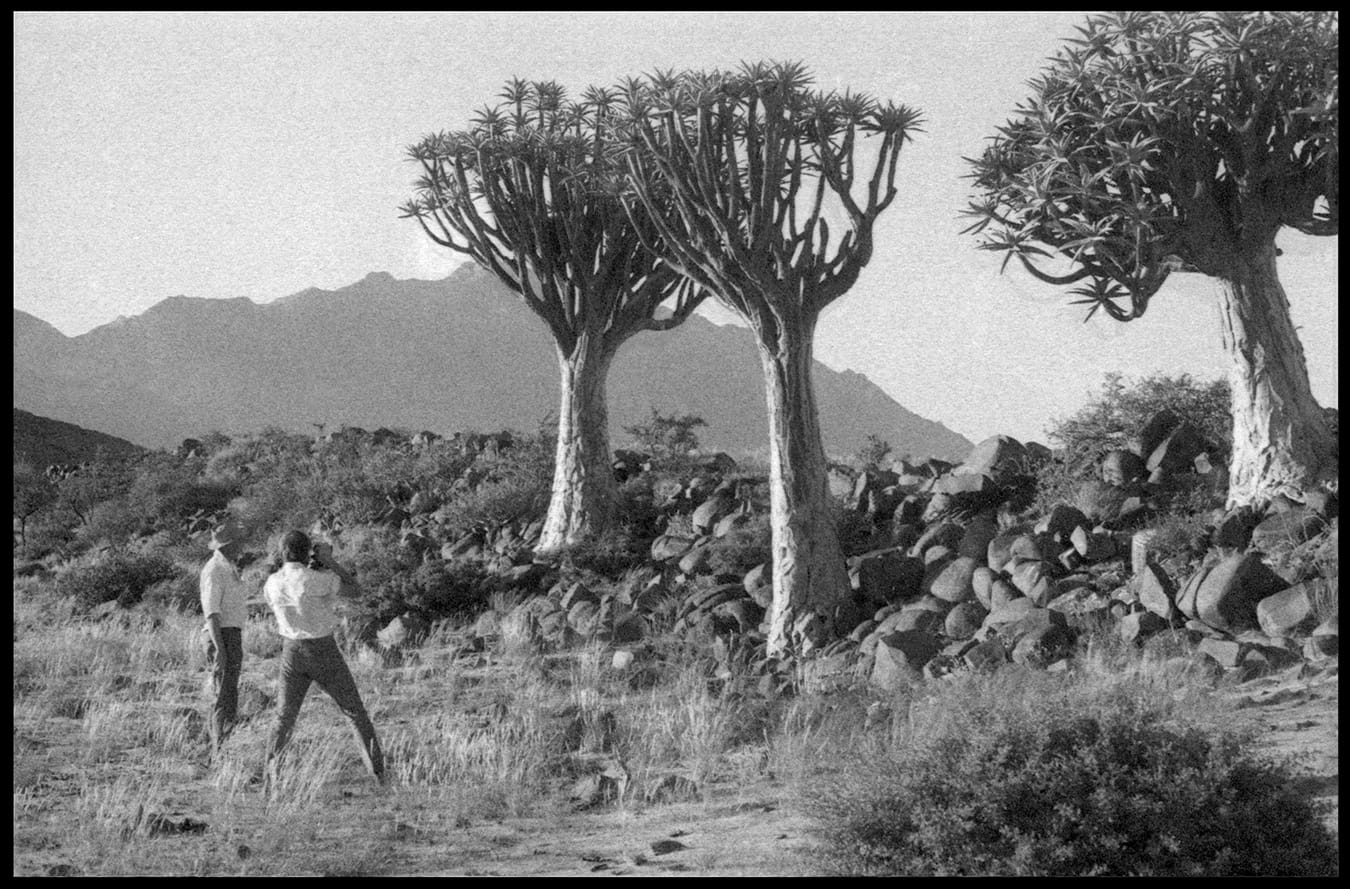

One of his early shipments of Boulat’s plates and Birkin’s own scouting Polaroids contained shots taken in the outback near Swakopmund, a coastal town they’d adopted as a kind of home base, since it was closer to areas of interest than Windhoek. Some featured a distinctively spiny, branching giant aloe: the quiver tree, or kokerboom in Afrikaans. Seeing these strange plants with their giant, wrinkled bark and fleshy star-shaped leaves, Kubrick grew excited. They seemed to convey exactly the kind of prehistoric exoticism he was after.

When Birkin called in from Swakopmund after a couple weeks in the field, Kubrick mentioned that he loved the trees. He didn’t like their current location, however. Could they be moved northwest to an area they’d been calling the Mountains of the Moon, and positioned there? Birkin said he’d look into it, and discussed the matter with Maartens, a fifth-generation South African who’d pioneered big-game hunting in the region. An old-school Afrikaner, Maartens had been visibly uncomfortable as Birkin fraternized with his black crew, but otherwise they got along reasonably well. He told his client that the kokerboom was endangered and protected by law, which was why the largest local concentrations had chain-link fencing around them. Some were over three hundred years old. Plus, they stored a lot of water, were extremely heavy, and would be difficult to transport anyway. Better to think of another plan.

When Birkin reported this to Kubrick, the director responded, “Well, I’m very fond of those trees. I’m sure you can find a way. You can just sneak in there and take a few.” Birkin thought this over. “What if I get caught?” he asked finally.

“You wouldn’t,” said Kubrick. “See if you can make it work, because it’s very important to me.”

Kokerboom trees.

Maartens, who told Birkin that his safari license was worth more than the risk of getting involved, nevertheless gave his client the number of a local trucking company, and Birkin rapidly established that while the job could be done, because of the risk it would be expensive. He’d need to rent two large trucks and a team of workers. It would cost about £400 to fell and move the kokerbooms—about $10,000 today. “Okay, well, do it,” said Kubrick. “Make sure you don’t mention MGM. Maybe pretend you’re Fox or something.”

Birkin hired two trucks and a dozen workers. “I had to do a lot of bribing,” he recalled. He was working for 20th Century Fox on a film project, he said, and they’d be driving south. Procuring a pair of wire cutters, he had Maartens start out with Boulat, Gire, and Archer in the direction of the Mountains of the Moon up north, and took his trucks and workers to a large fenced-in preserve that he’d already surveyed. Leaving the road in the late afternoon, they motored across the desert to a section well out of sight of any traffic. There Birkin himself snipped the fence, making an opening large enough to accommodate the trucks. With light beginning to fade, the workers set about sawing down two of the largest, most impressive kokerbooms. When they hit the ground, however, they broke into multiple pieces. The weight of their water had shattered their brittle trunks.

Standing amid the draining shards, Birkin was still instructing that the next ones be brought down more gradually with ropes—when an ominous buzzing resounded from the broken trees. A furious swarm of kokerboom hornets arose from the trunks. Yelling in agony from the stings, the workers scattered. Birkin, the only white man present, withdrew unscathed into a truck cab. After the insects had dispersed, his crew continued working, now under headlights. For every tree successfully felled, four lay in pieces. They loaded six reasonably intact trees onto the trucks, braced them with cork-stuffed bags, and set off across the desert, avoiding roads in case of pursuit and heading northeast.

Navigating with a compass and a flashlight, Birkin rode in the lead truck. Because the Namib is mostly flat and bare north of Swakopmund, they made reasonably good time—until they encountered a manifestly improbable sight: an ephemeral river, snaking through the gloom, evidently the result of a rare flash rainstorm upstream. As they drove along the bank to find an area shallow enough to cross, a laborer in the second truck lit a cigarette and unthinkingly flicked the glowing match amid the cork-stuffed bags. Within seconds, a brilliant yellow sheet of flame had erupted in Birkin’s rearview mirror. With one truck blazing from the back, the small convoy screeched to a halt, and everybody spilled in confusion out onto the desert floor.

Realizing that he’d better think fast, Birkin ordered that the flaming truck be backed up and its precious contents dumped into the river. Half their cargo spiraled into the night, surrounded by gradually subsiding flames from the cork bags. Restarting the trucks, they pursued the kokerbooms downstream. Eventually the trees rammed into a sandbar shallow enough for the workers to recover them. Being congenitally tough and heat resistant, they were surprisingly undamaged.

When they finally reached their location near the Maartens safari encampment late the following day, the workers helped set up the trees in several places by propping boulders around their trunks. Then leaving Birkin behind, they drove off across the baking desert—apparitional vehicles gradually vanishing in shimmering ripples of heat. And at dusk, Boulat set to work documenting a landscape suddenly festooned with transplanted kokerbooms.

Most of the pictures taken in Africa were framed with an emphasis on background and middle-ground elements. Foreground distractions had to be as few as possible, because the sets being constructed at Borehamwood would provide the foreground. As a result, only a couple of the trees that Birkin had transported so laboriously across the desert can be glimpsed, far in the background, in 2001’s man-ape prelude.

Still intrigued by the kokerbooms, however, Kubrick asked the MGM art department to fabricate some new ones, and several are prominently visible at the Dawn of Man. They were made in England.

• • •

Back in London, Dan Richter had recruited three others to assist him, including another refugee from the American Mime Theatre, Ray Steiner, a diminutive dancer named Roy Simpson, and Adrian Haggard, an untrained amateur with an “uncanny physical freedom that has him bouncing off the walls as an ape-man,” as Richter put it. Their work was predicated on the understanding that they’d be core performers in the prelude. With Stuart Freeborn busy in the background devising new methods to construct light, flexible costumes, they worked together under Richter to establish behaviors and body movements capable of transforming themselves into credible representatives of a long-extinct prehuman species.

Richter had rapidly established a kind of upper-body vocabulary based partly on chimpanzees, and partly on Guy the Gorilla’s chest-first way of moving. “They have a longer torso relative to the lower body, so by raising the shoulders and straightening the back, that movement translated,” Richter observed. As a result, he, Ray, Roy, and Adrian could transform readily into “chimps with a touch of gorilla”—at least above the belt. But the lower body was a different story. “The problem was these big human legs . . . they just didn’t work, they looked wrong,” he said.

Richter had gotten used to taking his Beaulieu to film the primates at the Regent’s Park Zoo, and one day, during a visit with his collaborators, he felt that his close observation of Guy and the chimps was yielding diminishing returns. He decided to pay a call on the gibbons—an Asian ape species characterized by fast, agile movements as they swing from branch to branch. Dan noticed that they periodically descended to the floor and walked rapidly across it, their arms raised for balance.

The walk is interesting because the gibbons are not knuckle walkers; they have long legs. Their walk has a swaying rhythm that seems to be an extension of their swinging from branch to branch. I point the Beaulieu at them and begin filming. Something is still wrong . . . They are moving too fast to be models for the man-apes. I sense that the movement is what I am looking for, but the speed makes the dynamic wrong. Suddenly I have an idea that really excites me. I switch the Beaulieu to half speed, forty-eight frames a second, and take more footage of them. Having exposed quite a bit of film, I put the camera down and move alongside of the cage with them, imitating their walk. One male gibbon gives me the queerest look. A crowd is starting to form and watch me.

The next day, the team gathered in Richter’s office to project the footage. “There on the wall, in black and white, is the solution,” Richter wrote later. “It’s uncanny. A gibbon walking in slow motion was the control. I could do it, describe it, and teach it. The initial stage of my choreography is finally complete.” He now had motion templates for both the upper and lower body. Kubrick’s intuition to provide Richter with a filmmaker’s tools had paid off.

Throughout his long working days at MGM, Richter was shooting a potent speedball: a blend of pharmaceutical-grade heroin and cocaine. As a legal addict, he was under the care and supervision of Dr. Isabella Frankau, “an aristocratic lady in tweed suits with a gold lorgnette hanging from a black ribbon, which she raises with deft aplomb whenever she needs to read something or write the coveted prescriptions.” The mixture, which he injected up to seven times a day, was designed not to get him high but to provide a highly medicated form of stability, with the cocaine countering the heroin to produce a simulacrum of normalcy. “Lady Frankau is convinced that addicts need to be stabilized with a constant and controlled supply of heroin and cocaine so that they do not go through the up and down cycle that most constantly experience with withdrawal symptom followed by being high again,” he wrote. Whenever Dan’s regular blend didn’t do the trick and the coke wasn’t keeping him “bright and alert,” he also always had some state-supplied methamphetamine on hand—crystal meth.

Although Dr. Frankau’s prescriptions allowed him to work more or less normally, Richter had a very large habit and estimates he was injecting thirty to forty times the quantities a street addict would use. So far, he’d managed to keep it under wraps, and he intended for it to remain that way. One day, however, he forgot to lock his office door while shooting up, and Roy Simpson entered without knocking. Dan assured his visibly shocked collaborator that he was registered and under government medical supervision, and he asked Simpson not to talk about it.

With Birkin scouting locations and sending Polaroids and large-format Ektachromes from the desert, Richter attacked the tricky problem of casting the Dawn of Man. At first, he’d resisted Kubrick’s assumption that he’d play Moonwatcher—he had more than enough work on his hands just casting and choreographing the sequence, he told the director. “It’s part of my nature, I guess; I really want to be wanted,” Richter said. “I think it was probably passive-aggressive behavior on my part. I wanted him to say, ‘We really need you.’ ” He laughed. “Because I think I knew that nobody else could do it.”

Meanwhile, Freeborn had been using his body cast of the performer to build a lightweight suit, and was working on a thinner, more sophisticated mask design as well, one permitting Richter to transmit a variety of facial expressions. In March Kubrick announced, “It’s you. We built the costume around you, you know how to do it. It’s you, and we’ll make everybody smaller than you.” This meant that Steiner and Haggard had to go—leaving only Simpson, who was shorter than Richter, as a potential performer. He could play a female, and Kubrick was planning to show babies as well—though how Freeborn would bring that off hadn’t been determined yet.

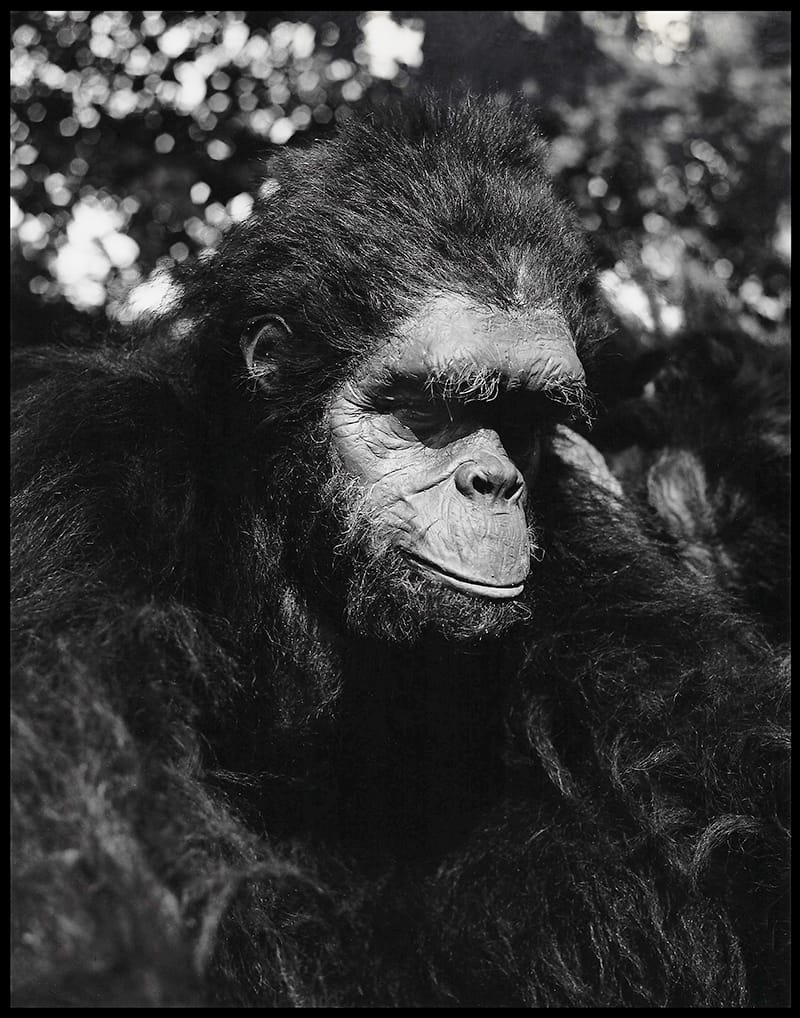

Freeborn’s extraordinary final mask.

The new height requirement further complicated Richter’s difficult casting process. They’d been advertising among jockeys, long-distance runners, and high school athletes, but even so, casting calls that winter had yielded only about six candidates with the stature required, out of hundreds of respondents. As a result, Kubrick had agreed reluctantly to reduce his tribe from sixty to about twenty—still a lot, given the weave of their net.

They seemed to have met an impasse, and meanwhile time was passing. Finally, the director came into the studio one spring day with a gleam in his eye. With three young daughters to entertain, the Kubricks’ TV was frequently tuned to hokey family fare, and a kids’ variety show featuring a dance troupe called “the Young Generation” had appeared on their screen the previous evening. The dancers were indeed young, and evidently chosen for their small stature so they would appear even younger. This could be the solution to their problem, Kubrick told Richter excitedly.

Richter immediately arranged that the Young Generation performers come by the dance studio in Covent Garden he’d been using for tryouts. “As I walk in . . . I have to work hard to hold back my excitement,” he wrote. “Here are enough performers to complete my tribe of man-apes. They are small, slight, and, best of all, while they look like kids on TV, they are all sixteen or older professional dancers—they can move!”

• • •

After photographing the Mountains of the Moon with their new, slightly singed trees, Birkin received help from Maartens’s safari workers to chop them up and dump them in a ravine. The kokerboom massacre was complete. A week or so later, he went on one of his periodic aerial sweeps, searching for vistas potentially of interest while the rest of the group traveled with Maartens to a new location. When he landed back in Windhoek, he received an urgent message: there had been an accident. The Land Rover carrying Boulat and Gire had slalomed off a dirt track and slammed into a rock outcropping, smashing the front end and breaking both of Boulat’s legs. He’d been rushed to the Windhoek hospital. Catherine was shaken but unhurt.

Having received dual plaster casts, a pair of crutches, and an envelope of cash from Birkin, Boulat flew back to Paris several days later. Catherine elected to remain, at least for a few weeks. “Stanley stopped his pay the minute that the crash occurred,” Birkin remembered. “Just like what happened to the crew members on board the Titanic when the last bit of water went over the top.” He gave a hollow laugh. “Then an insurance claim was filed.”

Kubrick rented new equipment and hired a well-known London fashion photographer, John Cowan, to replace Boulat. Famous for his energetic pictures of supermodels suspended in the air, an effect achieved with a trampoline positioned in front of various landmarks, Cowan was the basis for the photographer in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow-Up. His actual studio and darkroom had been central to the film—which also happened to include a brief but frisky appearance by Birkin’s sister Jane. Cowan showed up in late March in crisp new safari khakis, minus the pith helmet. He’d never shot in large format before but had brought a more experienced assistant who had.

He proved temperamentally unsuited for the job. In London, Kubrick had explained the narrow strictures of his role: Cowan was expected to photograph exactly the views that had already been chosen, at precisely the time of day specified, so as to achieve the required lighting. That way foreground sets could be constructed accordingly. Instead, he kept on saying, “I think this is more interesting,” and choosing his own angles—much to Ernie Archer’s exasperation. He also insisted on sending plates to London with conspicuous foreground elements to them, although it had been explained that they would be completely useless to the project.

After much bickering, Birkin’s compromise with the photographer was that he could take the pictures he wanted, as long as he also took what Kubrick needed. The director, however, soon became “pissed off with all these extra shots that were of no use to him,” Birkin recalled. When Kubrick’s complaints were passed on, Cowan, in turn, grew irritated that his artistic prerogatives were being disrespected. After a couple weeks of this, Kubrick decided to replace Cowan with Keith Hamshere, and on April 27 Birkin summarized the situation in a letter to his father: “We now have another photographer here—the fella from ‘Oliver!’ was hurriedly sent out following a hasty return of Photo No. 2. (Who got upset with Kubrick’s criticisms)—what a pain he was—always going on about The Shrimp & TwiggyII . . . It would have been rather different if he’d brought them along!”

When he returned to London, Cowan discovered that Kubrick was suing him for a week’s safari costs plus other expenses.

• • •

Stuart Freeborn had been recruited in 1965 with a phone call and letter from Kubrick promising an “interesting makeup film. Schedule: five months, maybe six.” He would be on the production for more than two years. This was almost entirely due to the Dawn of Man sequence. It was by far the most difficult job he’d ever had.

After his ape-man suit with a rubber pull-on mask had been deemed too thick and expressionless, Freeborn had followed it with his Neanderthals. Their augmented facial features had been built up, in a labor-intensive process, from foam rubber prosthetic pieces, and their crotches covered by light, flexible wigs. In the spring of 1967, his emerging solution to the challenge Dan Richter had posed—make a costume thin enough to allow a gestural, actorly expressivity—was a fusion of the two approaches. It had the great virtue of not requiring hours of work in the chair per subject to look right—something he couldn’t afford, even with a tribe of “only” twenty.

The removable full-head man-ape masks Freeborn devised were made of multiple highly flexible pieces of form-fitting foam rubber, or polyurethane, which fitted over an underskull of more rigid material tailored to the individual. The latter didn’t encase the performer’s head but served as faceplates attached by straps, and could be removed and replaced in seconds. The foam pieces were highly variegated, with different degrees of flexibility depending on their function. When layered properly, they gave the convincing effect of muscle and sinew at play. Even in the simplest masks made for secondary performers, Freeborn had devised a wonderfully economical hidden internal system of threads, such that when the actor opened his jaws inside, the top lip outside raised three fourths of an inch, and the bottom went down a half inch. Depending on the mood at hand, the effect was of either a highly realistic warning or a greeting. Certainly the exposure of fanged teeth—the only Australopith defense, at least until weapons came around—was an entirely believable threat display. With this innovation as a baseline for all the masks, Freeborn had already transcended the dreaded man-in-ape-mask cliché.

But this was only the beginning. From there, he worked on refining a way for Richter and the other principal performers to frown and use their tongues as well. Kubrick wanted his man-apes to be able to lick their lips weakly, in a sign of famine. In response, Freeborn had devised an internal mechanism permitting this action, which required the construction of believable mouths with dense foam rubber tongues that could extend and turn upward and downward to lick their lips. Each performer outfitted with this kind of mask had to have his tongue cast—not the most comfortable procedure. “I made a little acrylic cup that by suction fitted over the end of their tongue,” he recalled. “They could force their tongue in by biting on the cup, pushing their tongue in it, and then they’d release their own jaws. Then they could push their tongue out and operate it, and it worked perfectly.” The jaws themselves had small rubber bands inside to keep them closed most of the time. Opening them, however, required real muscle power.

A very small part of each performer’s face was visible through each mask: the area immediately around the eyes. This was made up to match the dark skin tone surrounding it, and all the performers wore dark brown contact lenses as well—which tended to vacuum up the dust of the set, fortuitously producing the wretchedly bloodshot effect Kubrick was after. The masks’ polyurethane layering thinned around the eyes and was affixed to the eyelid area by a type of sticky glue that remained viscous throughout, so that the performers could easily remove and replace the masks between takes.

Freeborn’s approach to the body involved creating what amounted to a body wig closely tailored to each performer: a thin, stretchy knitted wool with hair woven into it, augmented at the shoulders and at the small of the back with form-fitting urethane pads underneath. “It was lightweight, airy, comfortable to wear, and fitted perfectly,” he said proudly. He’d discovered that by weaving in hair of different consistencies and colors, he could create a more believable pelt, and after much experimentation, came up with a second skin for each performer that allowed air to circulate and was more flexible than even the leotard Richter had worn at his impromptu audition. Each ensemble contained human hair, yak hair, and horsehair, with the latter “down the spine, where you get longer, shiny, crispier hair,” Freeborn recalled. Velcro strips allowed the top and the bottom pieces to join, with hair combed over the seam.

If art is a form of fanaticism, one soliloquy Freeborn made to visual effects magazine Cinefex about a decade after 2001’s release provides a clear measure of how single-minded this unique artist’s pursuit of absolute realism was. It concerned the intricacies of his man-ape’s jaws, and specifically how to get them, and their lips, to close in a realistic manner.

For the performer to open the jaw, he would have to stretch the foam rubber on the sides of the face, which was difficult enough. In addition, he would need to pull cords and toggles to open the lips, top and bottom. So the performer’s jaw muscles really had to work to open the mouth of the mask. Then the mouth had to come back and close—which it did not want to do. We found that it would hang open a bit—both the jaw itself and the foam rubber mask on top of it—which looked silly. The problem was that once the rubber stretched and loosened up, no matter what we did, the mouth would never snap shut again with just the tension of the foam rubber cheeks. So we had two separate problems: making the jaw snap shut and making the foam rubber over it snap shut. Springs were out because they make such a noise, and they’re awkward to use. Elastic bands worked great for the first part of closing the jaw—but at about the halfway mark, they would get very weak and couldn’t close all the way. Finally, I tried using deep field magnets. I had seven magnets hidden in the teeth, so that when the elastic band began weakening, losing its power to withdraw back, the magnets would take over and shut the jaw the rest of the way. At first, I found that if the magnets were positioned exactly flat, facing each other, it was a helluva job for the performers to break that magnetic field and open the jaw. I solved that problem by tip-tilting them slightly. The magnets still had their power, but by putting them at a slight angle, there was enough give that the performers could open the jaw quite easily. It made all the difference.

I had seven magnets hidden in the teeth. Who other than Stuart Freeborn could have produced such a phrase?

Throughout this wizardry, Kubrick arrived periodically to evaluate the work and up his demands. “I saw him look at it,” Freeborn recalled in conversation with Richter in 1999, “and he went around, [going] ‘Hmmm, hmmm, hmmm.’ He never said, ‘Oh, that’s fine.’ Never, ever said that. ‘Hmmm, hmmm.’ And went out. But I knew that in his mind, he’s thinking, ‘The bugger’s done that, and if he can do that, he can do something else. I’ll think of something else he can do.’

“And damn me, the phone went, and it was him. ‘Stuart?’ he says, ‘I just got an idea. I’m writing in a scene now where I want to see them with their jaws closed, and I want to see them snarl with their teeth closed.’ ” He laughed. “There’s no reason for it. It was just that he knew that it was almost impossible for me to do that, because all the other mechanics was depending on the opening of the jaws that made everything work. And now he wants to see the lips still working, without the jaws opening. So they could snarl. He said, ‘I want to see them snarling.’ He was just pushing me, you know. I knew that.”

The British Empire was built on the uncomplaining execution of orders from the higher-ups. Entire subcontinents had been subjugated on that basis. It took a stiff upper lip to redesign his man-ape’s lips after so much effort had been put in already, but Freeborn set to work on the problem. He devised a single tongue-operated acrylic toggle that functioned as an internal lever. When the tongue was pushed against it, it pulled the internal thread system connected to the foam rubber lips, exposing the teeth with the jaws still clenched—producing a dangerous-looking snarl. Underneath lay an extraordinary accumulation of hard-won experience.

No matter how extreme the request, Freeborn didn’t ever say no. “He never yelled at Stanley or anything like that, but he would just grin and bear it and suffer,” Richter recalled. “He showed a lot of stress, and he was a perfectionist just like Stanley was. He’d work and work for days to get something, and Stanley’d say, ‘No, that’s not right. Can you change it?’ And, of course, changing it meant you had to work day and night for a couple days to make a change, which he’d bring, and Stanley’d say, ‘Well, that’s closer but still not right. Could you do this?’ I think other people would have just said, ‘Fuck this shit. I can go work on this other picture.’ ” Freeborn never even considered doing that. Throughout, he worked such long hours that he regularly slept exhaustedly in the car as his wife, Kathleen, who was working just as hard assisting him, drove him home in the early hours of the morning or returned him to Borehamwood at dawn.

Upon seeing the man-ape snarl that Freeborn had managed to produce against all odds—and contrary to all his prior designs—did Kubrick bare his own teeth in a smile? Actually, he remained unsatisfied. He wanted ever more nuance. He didn’t want a simulation of life, he seemingly wanted life itself. “So Stuart, in a surge of inventiveness, separates the toggle into two sections, each affecting a different half of the mouth,” remembered Richter.

It works! By balling my tongue and pushing both toggles simultaneously, I produce a very effective snarl. If I do it and keep my jaws wide, I produce the look of Moonwatcher roaring. Push the right one, and the right side pulls back. Push the left one, and it does the same on the left side. Rolling my tongue across them both produces a great effect. He has made the mask’s tongue hollow so I can put my tongue inside it. I can lick my lips!

Of course, all that slavering tongue action within the sealed confines of all the masks under the high heat of the film lights presented a new kind of ordeal for the performers inside. “Believe me, it was revolting,” said Richter. “And the only thing that kept me from vomiting was the realization that if I vomited inside that mask, I’d probably suffocate.”

On top of all these innovations, Freeborn remained keenly aware that Richter’s man-apes constituted different characters; they were individuals. “What I had was the positive of the artist’s head, plus the urethane rigid mask on top of it,” he recalled of constructing the masks on head molds in his studio before fitting them onto the actual subjects. “Well, now I have to build, on that, the patterns and indents as well as the outer shape of the foam rubber mask.”

The two things I had to think of were the age and the character of each particular ape-man. They’re all separate. I tried to fit the personality, the shape, the expression, and the age of the face I was modeling to the particular performer—I knew all of them fairly well at that point. I knew their personalities, which ones moved quite fast, which ones were slower in their movements, and so on. Of course, the slower ones I made the older ones. And so forth.

Throughout, he and Richter compared notes daily. It wasn’t just Kubrick who came to him with new demands; Dan was choreographing the sequence, and much of Freeborn’s work was in response to his imperatives as well. “Stuart and I are working together in what has become a very subtle manner,” Richter wrote. “He cannot build a costume with urethane from plaster molds alone, and I cannot create the illusion of a man-ape with movements alone. During the first few months, we slowly forged a way of working together that was very symbiotic. As a result, we have become very close. As Stuart’s frustration grows, our friendship and respect for each other grows as well.”

Asked about it a half century later, Richter said, “I think that both of us understood after a week or two that we were both onto something. I was working with this incredible artist who had changed film history and would go on changing film history, and he saw that he was working with somebody who actually knew how to make this thing work if he would work with me.”

The artist Richter was referring to was Freeborn, not Kubrick.

• • •

By late June, Freeborn had established a costume production line with the help of another leader in the field, Charlie Parker, who’d done makeup for films such as Ben-Hur and Lawrence of Arabia. As spring turned into summer, the stresses of whipping his band of twenty man-apes into shape—which came on top of preparing himself for the lead role—was starting to hit Richter hard. He’d been taking them through uncompromising exercises designed to build leg strength and purge any remaining vestiges of trained dancers’ movements, replacing them with a specific kind of wild, primitive energy—not random by any means but one adhering to the vocabulary of upper- and lower-body movements that he’d established and was now seeking to choreograph.

His goal from the beginning was to get his performers to establish kinship groups—with one of them led by One Ear, the rival gang leader to Moonwatcher. They’d watched films of Jane Goodall with her chimpanzees, and learned to exhibit various behaviors visible in them, including foraging, grooming, aggression, and submission. Incarnating an Australopithecus africanus required an intense physicality particularly hard on the lower body. The only way to disguise those long human legs was to crouch and weave, gibbon-style, with the knees turned outward most of the time. Accordingly, Dan had established a brutal physical training regimen—boot camp for man-apes. Every day, they met in the fields behind the studio, ran laps, and performed calisthenics.

Film productions, particularly extended ones staffed with unusually creative people, sometimes produce their own strange subcultural behavioral characteristics. Even without overtly simian conduct, they can be anthropologically interesting, and one of the ways that Doug Trumbull and his animators blew off steam was to go into the studio back lot, where he’d stashed a large rented trampoline, and take turns using it. In doing so, they had a fine view of rolling green meadows. The MGM back lot merged imperceptibly into pastureland and woods. Sometimes Doug went alone, and he distinctly remembers seeing Richter and his trainees shrieking at one another as he bounced up and down, “playing monkey amongst the trees and ravines and stuff. It was the weirdest stuff.” Asked if he’d sometimes wear his cowboy hat when he did so, he said, “A lot of the time. It was my signature as the young California kid.”

Picture, for a moment, the bouncing cowboy on his trampoline, hand on Stetson to keep it from flying off, observing from a distance the shaggy man-apes prowling among the back-lot trees, thinking they looked weird. As one snapshot among many, it could do worse in representing the multifarious backstage goings-on of 2001: A Space Odyssey during its last year of production.

• • •

Despite his hipster background and drug habit, Richter was something of a disciplinarian. He didn’t fraternize with his men, and he carried a three-foot wooden dowel—something his teacher Paul Curtis had called a “mime stick”—which he used to poke errant parts of performers who weren’t performing as well as the rest of them. “You were quite strict. You were a bit scary,” one of his tribe, David Charkham, told him in 1999. “You were the leader, you were definitely the boss. You were kind of on another planet at times; I didn’t quite understand what it was . . . You were slightly not all there.”

Apart from the incident with Roy, Richter had so far succeeded in hiding his addiction. When Freeborn had subjected him to full-body casts, he’d hidden his tracks with adhesive bandages. If Stuart had suspected anything, he was too diplomatic to say. As production neared and pressure grew, however, the drugs imposed an “awful burden,” Richter recalled. The hardest part was measuring the dosages so that he wouldn’t be sick from using too little, but also not groggy from using too much. “The only benefit I get out of it is that it keeps me very skinny, so I won’t look like the Michelin Man in my costume,” he wrote.

The strain of what he knew would be one of the most important creative commitments in his life had also affected Richter’s self-confidence. Like Kubrick, he sought to hide this from his subordinates. Increasingly aloof, he kept upping an already high drugs dosage. His daily interactions with the director and his regular attendance at screening sessions, in which the visual effects team projected spectacular footage of wheeling space stations in Earth orbit and atomic-powered spacecraft arriving at Jupiter, only drove home how high the stakes were. The Dawn of Man sequence would open this remarkable film, and its success relied significantly on him. “It was a pressure cooker,” he remembered. “You’re surrounded by the brightest minds of our generation, and you had to deliver. And you were in the spotlight. You couldn’t hide.”

One day as Richter was putting his monkey men through their paces, he started to feel a constriction in his chest and shortness of breath. Worried he was having a heart attack, he asked Simpson to take over and drove into town seeking medical attention. Scrutinizing Richter’s EKG readings, his doctor deduced that it was almost certainly stress and said he’d need to develop coping mechanisms. “They also recommended that I take less cocaine,” Richter recalled with a laugh.

The sole holdover from his original group, Roy Simpson, hadn’t been able to match the raw physicality of the young dancers then in their final preparations. Simpson had been kept on with the idea that his short stature and slight build would allow him to play a female, but Kubrick had decided that the females would all need to be significantly smaller than Moonwatcher, and with Freeborn now in the process of making individual costumes, they decided that Roy, who was about Dan’s height, would have to go.

It fell on Richter to inform him of this. Simpson, who’d been helping supervise rehearsals and training for months, didn’t take it well, and within an hour of his departure, Dan received a call from Kubrick’s secretary requesting that he come immediately. The tone of the summons worried him, and when he arrived, the director looked as somber as he’d ever seen him. “Dan, we’ve had a very serious complaint from Roy Simpson,” Kubrick said. “He said that you’re a drug addict, and you were trying to hold him down and make him take drugs.”

Richter was stunned. “It’s bullshit, Stanley!” he exclaimed. “Roy is hurt because we let him go, and he’s striking out.” Suddenly all of his work was in danger. Realizing that he was “scared shitless,” he thought, “That’s it, I’m finished.” In the stress of the moment, it didn’t occur to him that Kubrick needed him every bit as much as he himself wanted to finish what they’d started.

“He wouldn’t say something like that if there wasn’t a basis for it,” Kubrick said, making it sound more like a question than a statement. He scrutinized Richter solemnly with his dark eyes.

Dan realized he’d better confess immediately, and damn the consequences. Their whole project was clearly at risk, but he owed this man who’d invested confidence in him the truth. “Well, yes, I’m a drug addict,” Richter admitted. “But no, I didn’t force him, nor was I doing it around him. He did walk in on me once. I’m a registered addict. It’s all legal. And if you want, I’ll give you my resignation, and I’ll do whatever I can to help. I just want to make sure the project does as well as it can.”

Kubrick assessed the situation. “You’re legal?” he asked, intrigued.

“Yes, I’m legal, and I’m registered with the Home Office,” Richter confirmed, referring to the British governmental department in charge of immigration and law enforcement. “I’m not breaking any laws.” He told him about Lady Frankau and said that Kubrick could call her or his Home Office caseworker for confirmation.

“Well, if you haven’t done anything wrong or illegal, I want you to stay on,” Kubrick said. “I’ve got a lot invested in you, and I need you.” He admitted that Simpson’s story about being forced to shoot drugs had been hard to believe. With the tension ebbing, his curiosity kicked in and the questions came thick and fast: “How does it feel? What’s it like? How do you shoot up?” He was already converting the situation into another opportunity to absorb potentially valuable information about the world and its strange inhabitants.

Each performer would have a studio dresser assigned to him when filming started, and later Kubrick would arrange that Richter have a large dressing room with a private bathroom, so he could do what he had to do without his dresser knowing. “Suddenly we have an intimacy in our relationship that hasn’t existed before,” Richter observed.

• • •

To an untrained eye, the purposeful preparations under way in Stage 3 for the Dawn of Man may have looked like any other tableau of busy film workers in action. In fact, they were laying the groundwork for one of the most ambitious, technically complex shooting situations ever attempted. Everything about the front-projection technique pioneered at Borehamwood from August 2 to October 9, 1967, was new and untested. Front projection had never been done at such a scale.

After much trial and error, a giant, sixty-foot-wide backing screen had been covered with innumerable irregularly shaped pieces of 3M’s Scotchlite reflective material. The manufacturing process for it had produced an inconsistent reflectivity, so that if it had simply been hung in strips on the backing screen as received, the image reflected back at the camera lens from the projector would have displayed visible horizontal brightness and color variations—something like a bad TV signal. Effects supervisor Tom Howard set an army of MGM scenographers to work with scissors and glue. Their stochastic patchwork of Scotchlite fragments randomized the problem, thereby cheating the eye, which subliminally discounted the variations as a natural part of the background scenery and sky. This solution was only partial, however, and in the shots with minimal cloud cover, a kind of stipple effect can still be seen in the sky—particularly if you’re looking for it.

All the shots taken in South West Africa had been exposed at dawn or dusk. This allowed Kubrick and Alcott to light their sets in a specific way. In practice, they were meant to be largely in shadow, with the backgrounds brighter. The dawn, in other words, was a perpetual, controlled environment during the Dawn of Man. But those shadowed areas weren’t actually in shadow. In fact, they were well lit from above, and that light had to be totally even, as secondhand light from the sky usually is. Every effort had to be made to avoid multiple shadows being cast by the performers—a dead giveaway that a studio lighting situation was in effect.

All this was extraordinarily hard to manage, particularly at the brightness levels they required, and Richter recalled Alcott and Kubrick in “very collegial, very friendly, usually softly spoken” conversations as they grappled with complex lighting issues. “You know if you’d listen to him,” said Richter, referring to Kubrick, “he’d be saying, ‘Oh, John, I wonder if we should . . . I think we should do this; I’d like to.’ And if you listened to those words carefully, you’d say, ‘He just asked him to do something that’s going to be incredibly difficult!’ And John would say, ‘Okay, Stanley’ ”—here Dan muttered indecipherable words, imitating a conversation conducted in low tones. “It was all very quiet, but you’re flying at such an altitude!”

The requirement that they avoid the illusion-shattering effect of multiple shadows enforced a particularly high-altitude innovation. “He said to me, ‘Well, how are we going to do it?’ ” Alcott recalled of Kubrick. “And I said, ‘The only way to do it is to make the entire ceiling of the stage a big white sky.’ ” Working with a particularly innovative and creative lighting gaffer, Bill Jeffrey—who’d lit the entire film and was one of 2001’s unsung creative resources throughout—Alcott also devised an insanely precise studio lighting control system.

So I hung mushroom reflective-type globes from the ceiling—500-watt photo floodlights—and I covered the complete ceiling area of the stage with those, which worked out to about two to three thousand bulbs. So Kubrick said to me, “Well, that’s fine, but then we’ve got these mountains, and then it’s going to be all hot [overexposed],” which was true . . . And he said, “We’ll have to turn bulbs off over the mountains.” I said, “Well, the only way to do that is to have every bulb on an individual switch.” So he said, “Okay, put every bulb on an individual switch.” Normally, you’d never get anyone to go along with that. If you said that to a producer now, he’d say, “You’re bloody crazy!” And it was ridiculous. But Kubrick wanted the lighting to be true and real; so we had a switch for every light, and I was able to control every bulb on that set. I could light the ground level fully and then have perhaps only two or three bulbs lighting the higher areas. The heads of the departments hated the idea because it made a lot of work for them; but they made a switch for each light, which required something like eight miles of cable all together.

Watching this process with fascination, Richard Woods, who played Moonwatcher’s rival One Ear, had the presence of mind to take notes. He recorded thirty-seven rectangular crates filled with bulbs being hauled up to the ceiling, each the size of a bed frame and containing fifty 500-watt lights. Each light was controllable from below, making a total of 1,850 switches. This allowed for an extremely precise reduction of any hot spots that might emerge as the set’s higher elements were wheeled into place. With Kubrick examining Polaroids throughout the process, overexposed areas could simply be made to disappear by incrementally switching off individual bulbs.

With all that firepower on, however, the total per crate was 25,000 watts. With thirty-seven crates suspended high overhead, the “sky’s” total power was 925,000 watts. And that didn’t count all the brute lights that had been brought in on the sides, creating better definition and giving a sense of sunlight being cast across the landscape from near the horizon. For the upcoming battle scenes alone, nine brutes would simulate sunshine from the side. With each of them cranking out 25,000 watts, the sunlight alone was 225,000 watts. Added to the sky, Woods calculated that the Dawn of Man sets were lit by 1.5 million watts.

Unsurprisingly, temperatures in Studio 4 soon spiked well above 100 degrees—as hot as the Namib Desert in summer. By now, Freeborn’s costumes were far more permeable than the suit that Keith Hamshere had worn when he collapsed in similar conditions months before. Still, Woods remembered losing seven pounds during the first week of shooting alone—and like the other performers, he’d been hired specifically because he was already skinny. Concerned that the grueling conditions would impact his performers’ energy levels, Kubrick brought in a large refrigerator packed with sodas.

He also tried another technique, soon abandoned. “They brought in a big wind machine, which was on very low, because they didn’t want to create a dust storm,” Woods recalled. “They fed it with some enormous amount of dry ice, putting it in the intake and blowing cooler air into the studio.” But the temperature differential soon caused film lights to explode, and with glass raining down from the African sky, Kubrick ordered that the device be removed. Richter’s man-apes would have to endure actual desert conditions.

• • •

Apart from the heat, as Richter and his men began filming scenes that August, one of the problems that quickly cropped up was near asphyxiation. Freeborn’s highly realistic mouths with their prehensile tongues meant that the performers were almost as sealed inside as Bill Weston had been in his space helmet—all while performing highly strenuous movements. As a result, the carbon dioxide buildup was immediate. “You start to die,” Richter recalled. “It’s like being in the death zone on Everest; the minute you put the mask on and the lights go on, you’re starting to die. You only really have seconds before you can’t function anymore.”

Ranks of nurses were on standby at the peripheries in case the performers passed out. Each man-ape had to pop salt tablets twice a day. Compressed air tanks were used to flush out the costumes and masks between takes, with negligible results. The performers weren’t supposed to wear their head masks for more than two minutes at a time, and though Freeborn had created masks that were easily removable, in practice this was rarely possible during actual filming. Lengths of stiff hose were cut into sections and used to pry their magnetized, elasticized mouths open between takes, permitting some air to flow inside. Finally, Freeborn devised a “specialized breathing apparatus . . . by making what I call a schnoggle, a special cap—a seashell cap that fitted over their own nostrils, but just short of the shape of their nose—it had two little tubes going up their nostrils.” This allowed waste air to be expelled, partially ameliorating the problem. But the innovation came fairly late, and for most of the Dawn of Man, Richter’s troupe was bounding about in near agony as carbon dioxide built up and their red blood cells carried more and more of it—and less and less oxygen—to their straining muscles.

Man-ape David Charkham vividly recalled shooting the nocturnal scene when Moonwatcher’s tribe awoke at the mysterious appearance of the monolith and scampered out to investigate. “We had to wake up, run or jump around, and then I had to go up to it and calm down, and slow down, and I was breathing so hard, and my head was pounding. To then reach up and touch it, you know, it was so hard to do. It was so hard to not just collapse at that point. And to get down to those small, delicate movements.”

Charkham’s touching of the monolith came only after Richter was directed to do so. Because the Dawn of Man was shot entirely MOS—without sound—Kubrick and Richter could communicate throughout the filming, with Richter’s voice emanating from behind his mask, something he could achieve without actually moving Moonwatcher’s face. Kubrick hadn’t told Richter in advance that he’d asked a space-suited William Sylvester to reach out and touch the monolith with his gloved hand on the Tycho Magnetic Anomaly set nine months before.

“I had to be in a squat, and you get very tired,” Richter remembered. “And I had to have control of my body so my legs aren’t shaking . . . And I reached up, and I knew the camera was here, so I reached up, and I didn’t actually touch it; it looked like I’m touching it, but I didn’t actually touch it because my hands were covered in dirt, and I knew there were going to be a lot of takes, and I didn’t want to start getting it dirty.”

Seeing this, Kubrick said immediately, “No, no, I need you to touch it.”

Still in character, Richter’s muffled voice issued from behind his mask: “I’m afraid I’ll make it dirty.”

“That’s okay,” said Kubrick. “They’ll clean it up.” Afterward, he showed Richter his lunar monolith footage with Sylvester and told him he’d been trying to match that seemingly instinctive human gesture.

Animator Colin Cantwell, who’d arrived as a late hire from Graphic Films in Los Angeles, remembered watching the monolith scene being shot. “He was directing Dan,” Cantwell said of Kubrick. “Just seeing the stage and him calling out occasionally, you know, ‘Now back away from it . . . Yeah!’ It was so extraordinary as it was unfolding. Of course, Dan’s interpretation was extraordinary acting in its highest level . . . All of it without a spoken word. It was beyond goose bumps.” He laughed. “The intensity of that is really something to live.”

• • •