Dan Richter, transformed from Moonwatcher to Polka Dot Man.

AUGUST 1967–MARCH 1968

There are certain thematic ideas that are better felt than explained. It’s better for the film to get into the subconscious, instead of being pigeonholed by the conscious mind in the form of specific verbal expositions.

—STANLEY KUBRICK TO THE TORONTO TELEGRAM

With Con Pederson subsumed in the flight-control intricacies of the war room and Trumbull preoccupied with his complex visualization engines, 2001’s animations were languishing during the last quarter of 1967 simply due to the overwork of its top effects people. After consulting with both, Kubrick decided to call in the reserves in the form of another Graphic Films veteran: animator Colin Cantwell. Upon arrival from LA in August, Cantwell, then thirty-five, found Kubrick and his team in “the final stages and trying to bring it together in the best possible way against incredible odds.”

He discovered that two-thirds of the film’s animations were at varying stages of incompleteness and soon organized twenty-four-hour shifts. As a canny student of film—and in particular, Ingmar Bergman—Cantwell also developed a productive dialogue with Kubrick that he was careful to disguise when at the studio to avoid jealousies or rivalries.I Like Trumbull, he realized quickly that while the director was clearly master of his vessel, true collaboration was possible. “He wasn’t wasting any time, he was focused,” he remembered of Kubrick during the production’s last six months. “He was dedicated to what he was creating, he was listening for it, finding where it was, continually trying to build it to this complete thing. That film is what Stanley is. And the great thing was, the ‘is-ing’ of it—the verb of doing it—we all got sucked into that. How can this be done, and the excellence that had to be there. Everything had to have that excellence, or it couldn’t happen at all.”

Many of the spacecraft visible in 2001 were actually animations of still photographs placed in their cosmic contexts after repeated passes through the animation stand—a technique in which such convincing details as live figures moving in their windows could be added. Even “live” shots of spacecraft models were sometimes combined with cunningly positioned stills: for example, the turning space station with the Pan Am “Orion” shuttle in hot pursuit, a sequence in which the shuttle was actually a receding still. The Moon Bus and other spacecraft were depicted in much the same way, after Brian Johnson shot large-format photographs of them for this purpose.

One of Cantwell’s early suggestions influenced the film’s look in subtle but meaningful ways. He discovered that as a holdover from storyboarding, a lot of the sequences had been conceived “fundamentally at right angles . . . and one of the things I wanted to do was break things loose from right angles.” Although many of the individual components were “superbly usable”—for example, that rotating station—Cantwell saw better ways of depicting the shuttle’s arrival there and sought to introduce more diverse camera angles, including two-thirds views.

When he explained his idea to Kubrick, however, the director didn’t get it. So Cantwell cut pieces of cardboard into different shapes, making “a little kit . . . Just as a piece of rough art, it’s one element and pivots and double pivots . . . you could rotate the stars and rotate the ship’s trajectory independently so that you could picture in sequence, frame by frame, what would happen as the ship came up to the docking entry.” After using it to demonstrate what he meant, he quickly received the director’s green light. Cantwell’s visual intuitions were excellent, and Kubrick soon came to appreciate them.

Cantwell realized quickly that while realism was important in 2001, it was outranked by an ongoing quest for visual purity—for images powerful enough to elide verbal explanation and tell their own stories. “There’s a level of abstraction all the way through that Stanley never lost the importance of,” he recalled. “He was about images and their impact, and he kept being true to that, and it worked tremendously.”

The film is highly abstract, and that divergence between the words of the book and the experience of the film, I think, was at the core of what Stanley was trying to do. The further he got along in the process, the more he kept on focusing down to that core . . . Stanley was creating a set of experiences that would leap [the audience] past the near present to a further present, and some of the implications of all of this . . . They would feel that they really were experiencing it. There would be no question. It would not look like special effects. It would not feel like special effects.

In Cantwell’s telling, during the last months of its production, the identity of 2001: A Space Odyssey was being forged partly in its differences from the novel, which in critical ways was providing not something to emulate (“If you can describe it, I can film it,” Clarke quoted Kubrick saying in 1964) but rather something to part from—and even push against.

It wasn’t necessarily an interpretation Clarke would have disagreed with. In a telling echo of Cantwell’s language, the author described his role at a press reception prior to the film’s Los Angeles premiere in April 1968. “This is really Stanley Kubrick’s movie,” he said. “I acted as a first-stage booster and offered occasional guidance.”

• • •

One of the transitions that hadn’t been solved on Cantwell’s arrival was Bowman’s movement from the “real” space of Jupiter orbit to the hyperreality of the Star Gate. Early storyboards had conceived of an actual physical cut in one of Jupiter’s moons as the entrance. Another concept had Bowman encountering a giant monolith orbiting the planet, and approaching it in his pod. After seeing his own reflection, he was supposed to reach out a pod arm to touch it—thus echoing the actions of William Sylvester and Dan Richter—only to discover that it was the Star Gate entrance. Neither approach had proven easily realizable on film, however, and they hadn’t even looked right in drawings.

Another problem was how to convey what had caused the monolith to send its signal to Jupiter in the first place—thus setting the entire second half of the story in motion. Kubrick had already raised this as a topic of concern with Trumbull in their first substantive discussion, at the Tycho Magnetic Anomaly set in Shepperton two years before. In the script, the monolith was a solar-powered device and was supposed to be activated when exposed to sunlight for the first time in four million years. But how to convey this? It had been judged too difficult to accomplish at Shepperton and had been left until postproduction.

In late 1967 Stanley and Christiane were hosting regular weekend movie evenings at their home for the director’s inner circle, and Cantwell took to staying afterward for a bite. During a series of bull sessions between Kubrick and Cantwell that fall, talk turned to Ingmar Bergman’s use of symmetry, particularly in his 1960 film The Virgin Spring, which had particularly struck Cantwell because while most of its shots were asymmetric and highly composed, certain key scenes were almost perfectly balanced. This prompted Kubrick—already a Bergman devotee—to screen the film again, and the two of them discussed it further. According to Cantwell, they agreed that Bergman’s symmetries served as symbolic markers. “We chatted, and I suggested that also was an opportunity in the same way Bergman had used it,” Cantwell recalled. “[There] could be times where that symmetric departure would then serve as a nonverbal emphasis; a hitching post for people to link their experiences together at important pivot points.”

Certainly Kubrick’s taste for symmetry and his interest in Bergman predated his discussions with Colin Cantwell. But there’s reason to believe the animator’s contention that the film’s eerie alignments of the Sun, the Moon, and Jupiter’s satellites—always arranged along either the vertical or horizontal axis of 2001’s central totem, the monolith—were influenced by these late-night discussions. And they, in turn, were catalyzed by that epic opening Earthrise shot, which had predated Cantwell’s arrival and already depicted an eclipse of the Sun by Earth as seen from the vantage point of the Moon.

With this sequence and their Bergman discussions in mind, Cantwell proceeded to produce two of 2001’s most symbolically freighted shots. Filmed on the animation stand, they intentionally mirrored each other. The first was a seemingly low-angle view of the monolith, with one of Pierre Boulat’s Namib Desert cloudscapes beyond and the Sun rising above the rectangular object. A crescent Moon rounded out the composition at the top. Kubrick would eventually edit this into the Dawn of Man sequence not once, but twice—first for about five seconds at the end of the man-apes’ encounter with the monolith, and then later for a two-second flashback just as Dan Richter conceives to pick up a bone and start banging other skeletal remains with it.

The second composition was virtually identical, this time depicting the lunar monolith and the Sun in identical positions, only now with a crescent Earth above. While many in the audience may have missed it, in principle the latter shot took care of the problem Kubrick had discussed with Trumbull at Shepperton: namely, how to reveal that the monolith’s radio beacon to Jupiter took place when the Sun hit it. And it was, in fact, edited into the film at the moment William Sylvester and the other lunar astronauts were seen recoiling from that evidently very powerful signal.

Cantwell’s paired shots had a kind of tarot card quality, and were deceptively simple to make. In each case, the monolith was simply a piece of black artist’s paper cut at steeply sloping angles and placed on top of large-format eight-by-ten-inch transparencies (in one case, of the Namib sky; in the other, a star field). The crescents Moon and Earth were added respectively in additional animation passes. As with the Earth occultation shot, the sun was a quartz halide light positioned behind a hole cut in black aluminum. Called “Upblock One” and “Upblock Two” in war room parlance, the shots provided a vivid illustration of how in film editing, context is everything. The live-action sequences that preceded each gave the audience a sense of the monolith’s scale and importance. The second brief use of the shot in the Dawn of Man signaled the object’s power over Moonwatcher’s imagination as he gradually intuits his way to the use of a weapon. Although powerful as stand-alone images, Cantwell’s symmetrical “pivot points” received their significance from their surroundings—including that opening Earth-occultation shot.

In the case of the Moonwatcher edit, they also provided Kubrick’s realization of the promise implicit in his dismissal of Clarke’s solution for the scene: the one where the monolith was seen manipulating the man-ape like “a puppet controlled by invisible strings.” In June 1966 the director had responded, “The literal description of these tests seems completely wrong to me. It takes away all the magic.” His solution now—essentially an attempt to introduce magic—was an example of how some sequences of 2001 functioned almost as a rejection of the novel’s approach. (It was, however, also a filmic illustration of Clarke’s famous third law: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Here as elsewhere, Kubrick may at times have had a more intuitive grasp of Clarke’s principles than even the author did. For his part, however, Clarke observed in 1969 that he and Kubrick had consciously “wanted to hint at magic, things that we could in principle not understand at this level of our development.”)

That still left the transition from Jupiter orbit to the Star Gate as an unsolved problem. On arrival at Jupiter, Bowman was to leave Discovery in his pod and approach . . . something remarkable. But what? Here, too, Cantwell’s pivot-point symmetries helped provide a solution. Trumbull had already worked out a derivation of his slit scan rig devoted to turning flat artwork representing Jupiter into a realistic, seemingly three-dimensional form. His Jupiter machine involved mounting dual projectors on a soundstage and linking them to an arc-shaped strip of reflective material. The strip, in effect, was a curving version of a slit. The projectors were loaded with two shots of Trumbull’s airbrushed painting of Jupiter—one for each hemisphere. When the whole rig rotated—with the projectors, the reflective arc, and the camera all linked by selsyn motors—Trumbull’s painting magically morphed into seemingly three-dimensional space as the turning crescent recreated it frame by frame. Today this would be called “texture mapping,” and would be conducted digitally.

With a convincing rendition of Jupiter having been accomplished, Trumbull and Cantwell worked together to produce the planet’s retinue of moons. Projecting Trumbull’s airbrush renderings of them onto white spheres—a less sophisticated version of his Jupiter machine technique—they photographed each at various phases. Cantwell then used the animation camera to experiment with representations of the Jovian system. All of Jupiter’s satellites orbit on the same plane, and in late October, Cantwell conceived of a view from the planet’s equator. “Once again, we go for the symmetry at the key point,” he said. Arranging the moons in a vertical line, he positioned Jupiter itself at the bottom. If alignments of the Sun, Earth, and Moon started 2001, signaled the power of the monolith, and marked the beginning of its second act, this new celestial arrangement would anchor the opposite end of that axis, opening the film’s metaphysical last chapter.

Having left a gap in his chain of Jovian moons, Cantwell proceeded to film a six-foot-long “baby” monolith turning against black velvet, where it seemed to disappear and reappear in deep space. “It was just lit and shot on a stage with a motor running it like a barbecue spit,” he remembered. “The black block element was shot to fit a particular location on the screen, and the other elements were just designed as a storyboard.” In his final arrangement, the rotating monolith was the horizontal bar of a cross, with a vertical lineup of five moons serving as its upright element, and Jupiter as the ground. A piece of neo-Christian symbolism had found its way into the proceedings, almost by osmosis.II

Because the lineup of moons was reminiscent of a slot machine window, Cantwell’s celestial cross was soon dubbed “Fifty Free Games” in war room vernacular. Throughout his colleague’s work on the shot, Trumbull had been making a new kind of slit scan sequence that seemed to emerge out of darkness. Its initial, almost subliminal tendrils of light vaulted toward the viewer, rising to full kaleidoscopic pitch over a period of eight or ten seconds—an effect he heightened by his use of “a little accelerator motor to make the effect keep going faster and faster.” The variable speed produced an effect not unlike the neurotransmitted uptick in stimulus characteristic of the psychedelic experience.

On seeing Cantwell’s Fifty Free Games shot—which he called “brilliant!”—Trumbull had it loaded into one of two projectors in the screening room, put his new slit scan shot in another, and then he and Cantwell experimented with a kind of dual-projector live mix, arriving ultimately at an understanding that if the animation camera was made to tilt up from Cantwell’s Jovian crucifix to the blackness above, Trumbull’s new slit scan shot could take over, effectively throwing the Star Gate wide open.

They’d figured out how to take David Bowman “Beyond the Infinite.”

• • •

Throughout the fall and winter of 1967, Kubrick pushed himself to the brink of physical and mental endurance as he tried to finalize 2001’s music, sound effects, narration, documentary prelude, and credit sequence. Cantwell estimated that during his tenure at Borehamwood, the director “probably worked close to a hundred hours a week, plus or minus, every week. How long he’d been doing that, I don’t know, but that’s a kind of obsession close to insanity. It’s creating something that hasn’t been in this world.” He compared what they were doing to “vision hacking.”

Until quite late in editing, Kubrick evidently still intended to show Roger Caras’s documentary prelude featuring interviews with world scientists discussing themes such as extraterrestrial intelligence and interstellar flight. He was also in a constant dialogue with Clarke concerning the film’s expository voice-over narration.

Having witnessed the Dawn of Man being shot, Cantwell was surprised and disturbed to discover some of these intentions. During one late-night discussion, the director also revealed his plan to incorporate the woodcut designs of Uruguayan American artist Antonio Frasconi for 2001’s credit sequence. A master of this printmaking genre, Frasconi was the author of numerous illustrated books. His most recent, The Cantilever Rainbow, had featured stylized depictions of solar eclipses and other primitivist depictions of the Sun. Their handmade, retro quality didn’t sit right with Cantwell, however. “The lead-in titles were to be over those backgrounds and would have title art superimposed over these almost childlike graphics,” he recalled. “That seemed so discordant compared with the Dawn of Man that it bothered me a good bit.”

Another thing that struck him as problematic was Caras’s interviews. Cantwell seemed to have found diplomatic, low-key ways of transmitting his views to the director. Kubrick’s process included a fairly frequent monitoring of his close collaborator’s opinions. In effect, their reactions provided navigational markers, helping him understand how entrenched his own positions might be. Cantwell may have intuited that rather than volunteering his opinion—something which didn’t necessarily go down well—he should simply wait to be asked. In any case, when his views were solicited, he “recommended to Stanley, the Suns of Frasconi’s shouldn’t be ahead of the Dawn of Man, and that the wordlessness of the Dawn of Man is exceedingly important,” he remembered. “The purity of the start had to not have the scientist’s verbal prologue in the wrong half of the brain.”

This distinction between verbal and visual, the left and right cerebral hemispheres, colored his recollections of Clarke’s visits to Borehamwood as well. “He would come in with a new narration to explain a whole section of the film that he had seen last time,” Cantwell said. “He thought that about three or four or five minutes’ worth of narration would take care of the uncertainties and puzzlement these scenes would create.” Kubrick would then screen new material for his collaborator, and each time, “Stanley would have taken out more of the dialogue, more of the thing was being handled nonverbally . . . So this polarity would be clearly there between them.”

When Clarke registered his worries over what he saw as the film’s growing opacity, Kubrick effectively steered him back to the novel, saying, “Don’t worry about it, Arthur, just put it all in exactly as you’d like to have it. Make the story clear in any way you want, it’s your book.” At this, Clarke would seem “anxious or subtly frustrated,” Cantwell observed. “Arthur was very subtle in what he was expressing, very polite.”

As their paths diverged during the last six months of 2001’s production, Kubrick’s aesthetic differences with the novel—and psychological distance from it—appeared to be growing.

• • •

When he started editing in mid-October, however, Kubrick gave every indication of using Clarke’s narration, and he’d spent much of 1967 looking for a good voice. As early as February, he’d asked Caras to contact Alistair Cooke, the Guardian journalist and BBC radio commentator, to see if he’d consider auditioning. By July, Caras had left for another job, and Kubrick asked his replacement, Benn Reyes, to help him find a voice similar to Canadian actor Douglas Rain—narrator of Universe, the film already so influential in 2001’s look. Rain was then unavailable, but after almost a hundred screenings of Universe, Kubrick seemingly couldn’t get his voice out of his head. “I would describe the quality as being sincere, intelligent, disarming, the intelligent friend next door, the Winston Hibler/Walt Disney approach,” he wrote Reyes. “Voice is neither patronizing, nor is it intimidating, nor is it pompous, overly dramatic or actorish. Despite this, it is interesting.”

Throughout his search, Kubrick used Hibler, who’d narrated many Disney films, as a touchstone. By September, he was negotiating with Rain directly, and he wrote New York radio producer Floyd Peterson, who’d been helping him record auditions, to tell him he thought the actor’s delivery was “perfect, he’s got just the right amount of the Winston Hibler, the intelligent friend next door quality, with great sincerity, and yet, I think, an arresting quality.” He asked Peterson not to approach Rain directly, however, as it might cause him to up his price—ending with “Remember this point, it’s important.”

In early August 1966, Kubrick had brought Oscar-winning American character actor Martin Balsam into the recording studio to play HAL. Although he initially found Balsam’s rendition “wonderful,” he realized gradually that he’d allowed him to make the computer sound too emotional. Having succeeded in luring Rain to read Clarke’s narration, at some point in the fall of 1967, he decided the actor should play HAL instead—and temporarily tabled the narrator question.

Rain flew in to London in late November and recorded HAL’s voice in only two days, most likely December 1 and 2. Much to his own dissatisfaction, these recording sessions, totaling only eight and a half hours of work, would become a definitive moment in his career. As an outstanding stage actor, Rain’s faceless channeling of 2001’s computer wasn’t necessarily what he had in mind as the role of a lifetime. According to Jerome Agel, the editor and mastermind of the innovative, image-heavy 1970 paperback The Making of Kubrick’s 2001, the director had hoped Rain would give HAL an “unctuous, patronizing, neuter quality.” In this, he wasn’t disappointed, though he found ways to help the impression along in postproduction. For his part, Rain found Kubrick to be “a charming man, most courteous to work with. He was a bit secretive about the film. I never saw the finished script; never saw a foot of the shooting.” He would play HAL in a vacuum.

The recording sessions gave Kubrick a last chance to refine the computer’s character, and he spent the second half of November rewriting key passages. Some of HAL’s most memorable lines emerged just before Rain’s arrival. One in particular—his response to a question from a BBC journalist—seemingly does double duty as a description of the director’s experience over the previous four years: “I am constantly occupied. I am putting myself to the fullest possible use, which is all I think that any conscious entity can ever hope to do.” Another set of lines replete with layers of Kubrickian irony seemingly encompasses all of history’s disasters. Asked by Bowman to account for his mistaken fault prediction concerning Discovery’s antenna guidance unit, HAL replies, “Well, I don’t think there is any question about it. It can only be attributable to human error. This sort of thing has cropped up before, and it has always been due to human error.”

During the session, Kubrick sat four feet away from the actor, and they went through the script line by line, with the director making small revisions as they proceeded. According to one account, Rain’s bare feet were on a pillow throughout, “in order to maintain the required relaxed tone.” Occasionally Kubrick intervened, asking the actor to speed up his delivery, act “a little more concerned,” or make it “more matter of fact.” As with Dullea’s responses the year before, quite a few of Rain’s Brain Room scene lines would later be lost in editing, including many of HAL’s increasingly desperate entreaties. One in particular that didn’t make it into the final cut showed multiple penciled revisions by Kubrick, finally becoming Rain saying “I’m sorry about everything. I want you to believe that.”

Kubrick could only have been satisfied with how Rain handled the scene where HAL seemingly wanted to confess his knowledge of their mission’s true purpose—another part of the session transcript in which various penciled revisions are visible. The actor managed to transmit the computer’s sense of divided loyalties as he asked Bowman if he minded being asked a personal question. Hearing “not at all,” HAL launched into several observations about events he found “difficult to define” and “difficult to put out of” his mind. “Perhaps I’m only projecting my own concern about it,” he said, observing that he’d “never completely freed myself from the suspicion that there are some extremely odd things about this mission.” Prompted by Bowman’s noncommittal responses, HAL elaborated, citing rumors of “something being dug up on the Moon,” and “the melodramatic touch” of the hibernating astronauts having been trained separately from the waking ones and brought on board already in hibernation.

Throughout this sequence, Rain’s performance gave the sense that all Bowman really needed to do was give him an excuse, and he’d readily spill the beans about what he knew. Instead, Bowman said, “You’re working up your crew psychology report” (a statement, interestingly enough, betraying the inherent assumption that the only crew psychology that could possibly be in question was human). At this HAL skipped a beat, and then retreated, affirming, “Of course I am.” (A pause that Kubrick could have inserted in editing.) Immediately thereafter, the computer predicted the failure of Discovery’s antenna guidance unit, and the moment had passed. He’d told two overt lies—that the unit would fail and that he was indeed working up such a report—and after that was on a murderous trajectory.

Kubrick had Rain sing, hum, and speak “Daisy Bell (A Bicycle Built for Two)” fifty-one times at various pitches and speeds, sometimes with uneven tempos, sometimes in a mix of hummed and spoken words, and once as a spoken-word piece enunciated in a monotone. In one take, they methodically went through the song five times in five keys: E, G, B, D, and F. Harry Dacre’s little ditty would be the yardstick by which HAL’s final disintegration would be measured, and the director was determined to give himself every possible interpretive variation.

After the session, Kubrick felt Rain’s line readings and singing were excellent but the former still required an extra measure of phlegmatic placidity. Using a new analog recording device called an “Eltro Information Rate Changer,” he slowed down the tape speed by between 15 percent and 20 percent without changing the pitch of the actor’s voice. In two passes over the device, Kubrick also modified his chosen take of HAL’s swan song, this time gradually dropping Rain’s pitch almost to zero as he sang “Daisy Bell”—all without changing the tape speed or song length. The second pass did stretch the length, but not as much as the pitch seemingly indicated. The net result was an eerily clear sonic portrait of HAL’s dissolution as his consciousness gradually declined to zero.

It’s no surprise that Kubrick didn’t use his shot of the computer’s eye going dark. The sound design did it for him.

Not long after, Cantwell came to see Kubrick in his office and was steered toward the editing rooms in Building 53. Hearing through the flimsy prefab walls that the director was working, he chose not to interrupt and waited outside. With the sound rolling across one head of the Moviola film editor and the picture on the other, Kubrick occasionally rewound back to the middle of the scene and replayed it, gauging its effect. Standing in the drafty hallway, Cantwell heard HAL pleading for his life: “I’m afraid, Dave . . . My mind is going.” As he listened, the computer regressed to its first lesson and, with Bowman’s encouragement, launched into his song. When Rain arrived at the line “I’m half crazy, all for the love of you,” the scene’s cumulative power hit Cantwell, and he discovered to his surprise that tears were streaming down his face.

When he finally entered the room, his face was still wet, and he was unable to speak. Quietly and without comment, Kubrick ran the entire scene for him.

• • •

Apart from his use of classical music, Kubrick’s sound design in 2001 is rarely commented on, though it’s no less innovative than the rest of the project. In particular, entire sections of the film have nothing but breathing and a muted feed of air as Bowman and Poole conduct their spacewalks. A similar respiratory soundscape is heard during Bowman’s methodical deprogramming of HAL and on Bowman’s arrival in the hotel room.

Like the heartbeats sometimes cut into horror films at moments of maximum tension, only with a bit more subtlety, these breaths give the audience a subjective sense of shared humanity. Without necessarily being conscious of it, we monitor Bowman’s emotional state by the tempo of his breaths. As virtually the only sound heard during the space walks, this element of 2001’s sound design also provides a sonic picture of the human organism suspended in the immensity of interplanetary space. Then, just as we get used to his rhythmic, oxygen-fed susurrus, Kubrick introduces another bravura element as Frank Poole struggles to reconnect his severed breathing hose. He does so not by addition but subtraction—definitively breaking the umbilical cord to Earth’s atmosphere by cutting the sound to absolute zero. Finally, we see Poole drifting lifeless in the vacuum, a receding figure lost in a star-spangled infinity. By willfully ignoring the implicit sound-design imperative to always keep something on the soundtrack, even if it’s just ambient “room tone”—by cutting to nothing, rather than something—Kubrick underlines the finality of what’s just happened.

Similarly, back on board Discovery, sound plays a key role in the weirdly disembodied erasure of the deep-frozen hibernators—perhaps the strangest mass murder ever committed to film. As Bowman flies off to retrieve Poole’s drifting body, the medical readouts gradually flatline, intercut with blinking warning messages such as “Computer Malfunction” and “Life Functions Critical” as a panoply of warning beeps and rapid electronic pulses synched to these messages paints a stark sonic picture of incipient emergency. Finally, the sounds stop dead at “Life Functions Terminated”—much as all sound had ceased with Poole’s last breath. And yet apart from the messages transmitted by their EKG and heart-rate indicators, nothing untoward appears to have happened to the entombed astronauts. Their transition from life to death seems entirely virtual. As French composer and film theorist Michel Chion has observed, “Death is inflicted like an act outside time. Nothing has changed.”

Another kind of execution unfolds during the Brain Room scene, during which Bowman’s arrhythmic breathing is the only response HAL hears for most of his final minutes of consciousness, something accentuating the stark difference between living and synthetic forms of life. The intermittent respiration on 2001’s soundtrack for the entire last half of the film also helps enforce the first-person effect that was one of Kubrick’s overtly stated goals. The breather is meant to be somebody—a character in a film—but also an everybody: all of us in the audience. It’s what makes the sudden cut to no sound at Poole’s death so visceral. It’s the presence of an absence, arrived at with guillotine speed.

That October, David de Wilde took a young assistant editor, John Grover, to meet Kubrick for the first time. With editing now under way, various soundtrack elements needed producing, and Grover had been delegated to supervise that day’s recording. He was nervous. Upon arriving at Kubrick’s office door in Building 53, he was startled to see the director leaning back behind his desk, a nasal spray inserted in each nostril. This unusual sight failed to faze de Wilde, however. “I was used to Stanley, so it didn’t surprise me, and he obviously had a cold and was clearing his head, for the recording.”

On seeing his visitors, Kubrick coolly extracted the sprays, picked up the helmet parked on his desk, and the three of them proceeded to Theater 1, which functioned as a large recording studio. There de Wilde introduced him to J. B. Smith, the studio’s chief dubbing mixer. With Grover’s help, they ran a microphone from the soundboard in the theater and positioned it next to Kubrick’s face, after which he lowered the helmet onto his shoulders. Then time passed, and nothing much happened. Decongested, ready to respirate, the director was breathing as usual—but it wasn’t being recorded. De Wilde watched him with amusement. He’d never seen Kubrick’s bearded visage in one of 2001’s helmets before: the creator, now part of his creation. The soundproofed theater was deathly silent. After an attempt to ask what was going on via the microphone, “Stanley lifted the helmet up and asked me what was the holdup,” de Wilde recalled. “My answer was that J. B. was deaf. He was not amused at the thought of a deaf sound mixer.”

Finally, Smith was ready to roll, Kubrick lowered the helmet, and the small team recorded about a half hour of him breathing. Later, 2001’s sound editor Winston Ryder looped the tape for use in editing.

In his novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce had his hero, Stephen Dedalus, observe, “The artist, like the God of creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails.” As an example of his own handiwork, Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey bears evidence of his own life within it, a small segment of his human soundtrack on Planet Earth from July 26, 1928, to March 7, 1999.

It was also, undeniably, a form of acting.

• • •

One of the more macabre documents to survive from 2001’s years of production was a cable, written on May 31, 1966, from Roger Caras to General Biological Supply House in Chicago. “Please advise return cable availability preserved human embryos indicating stage of development price delays etc. Also availability best quality models of same,” it reads. A cable from Ivor Powell to Caras had preceded it, requesting original prints of Lennart Nilsson’s sensational 1965 embryo photographs in Life.

A terse communiqué soon ricocheted back from Chicago: “Cannot offer quotations or supply hum embryos or model sorry.” With no genuine terminated fetuses forthcoming, by the fall of 1967, Kubrick had decided to produce the apparitional “Star Child” of the film’s final sequence in Borehamwood, and he recruited a talented young sculptor, Liz Moore, for the task. Moore, who’d helped Stuart Freeborn with his man-ape costumes, had already made something of a name for herself as a student by sculpting clay busts of the Beatles. That summer she produced a clay rendition of a human embryo with features eerily similar to Keir Dullea. As per Kubrick’s requirements, it had an abnormally large head, meant to signify humanity’s next evolutionary stage. “Originally it was going to be much more complex, mechanically, with arms and fingers that moved,” remembered Brian Johnson. “But then Stanley had the idea of surrounding it in a cocoon of light, and in the end decided that all he really wanted to happen was for its eyes to move.”

After it had been molded and reproduced as a hollow resin-coated flesh-toned figurine about two and a half feet tall, Johnson set to work on the sculpture, inserting glass eyes into the head through a removable skullcap. Connecting the eyes to small rods, he motorized them by attaching them to selsyn motor-controlled bearings—2001’s ubiquitous motion-control tool. “If you look at automatons that were made in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it’s the same sort of principle,” he observed. Johnson’s motors governed the fetus’s eerie lateral gaze.

In early November they positioned the Star Child in the studio, surrounded it with black velvet, and did a series of camera passes. The footage was far too crisp, however, and required serious diffusion, so they deployed another of the film’s visual effects secret weapons. It had been “provided by Geoff Unsworth, and he called it ‘prewar gauze,’ ” Trumbull recalled. “He had this very limited secret cache of prewar gauze, which was, like, 1938 silk stockings that created the most beautiful glow, which was used on the Star Child and a lot of other shots in the movie.” Rumor had it the material originally came from Marlene Dietrich’s pantyhose drawer, but in any case, because a given percentage of the light passed straight through the material from the sculpture to the lens, a beautifully atmospheric diffusion could be produced without reducing the underlying sharpness of the subject. Ultimately all the slit scan and Jupiter footage was reshot through Unsworth’s precious prewar gauze, producing the unearthly glow much in evidence during the film’s final half hour.

Moore’s sculpture was filmed again, now through about fifteen layers of gauze, Trumbull recalled, “with about forty thousand watts of backlight—something like four big arc lights to rim-light it, and [we] got this tremendous, overexposed glowing effect . . . Stanley filmed a number of different moves on the Star Child—shots of it entering frame and sliding through frame and so on. Then I airbrushed the envelope that surrounded it onto a piece of glossy black paper, which was photographed on the animation stand and matched in movement to the model, also with a lot of gauze and overexposure.”

Of these camera passes, only two were used, plus a pair of stills, with the latter fused via animation stand wizardry to different views of Masters’s Louis XIV hotel room deathbed—now evidently the site of a resurrection—then wreathed in airbrushed nimbuses of light. One of the two live-action takes, the last shot seen in the film, revealed the embryonic child gradually turning, its eyes taking in the Earth and then panning farther still, breaking the theater’s fourth wall as its gaze swept across the audience. Accompanied by the triumphant fanfare of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, it was one of the twentieth century’s indelibly powerful cinematic moments.

Cantwell’s celestial alignment, Dullea’s last supper, and, finally, the death and resurrection of Discovery’s surviving crew member all seemingly conspired to put 2001’s audiences into a theological frame of mind. But even without the surrounding context, Moore’s sculpture with its autonomous eyes evidently had an extraordinary, even supernatural presence. The powerful studio lights illuminating the Star Child gave it an otherworldly radiance against the black velvet that surrounded it. The flesh-toned skullcap permitting access to its inner mechanism had been joined seamlessly to the rest of its head with a waxy fixative. Long exposure times per frame were required to achieve the partially overexposed effect Kubrick wanted. Some of those camera passes took eight hours or more to accomplish.

Only one unit camera operator was required to monitor this lengthy process, and he didn’t give it his undivided attention. During one long filming day that winter, the heat of the powerful arc lights melted the sculpture’s fixative, which gradually spilled down inside its hollow skull, finally emerging at the corners of its eyes as perfectly formed drops. And on one of his periodic checks, the cameraman was amazed to see the Star Child weeping real tears.

Shocked to the core by the supernatural sight, “the operator ran away screaming his lungs out,” recalled Daisy Lange, Harry’s wife. “Now that I think about it, maybe he was a devout Catholic.”

• • •

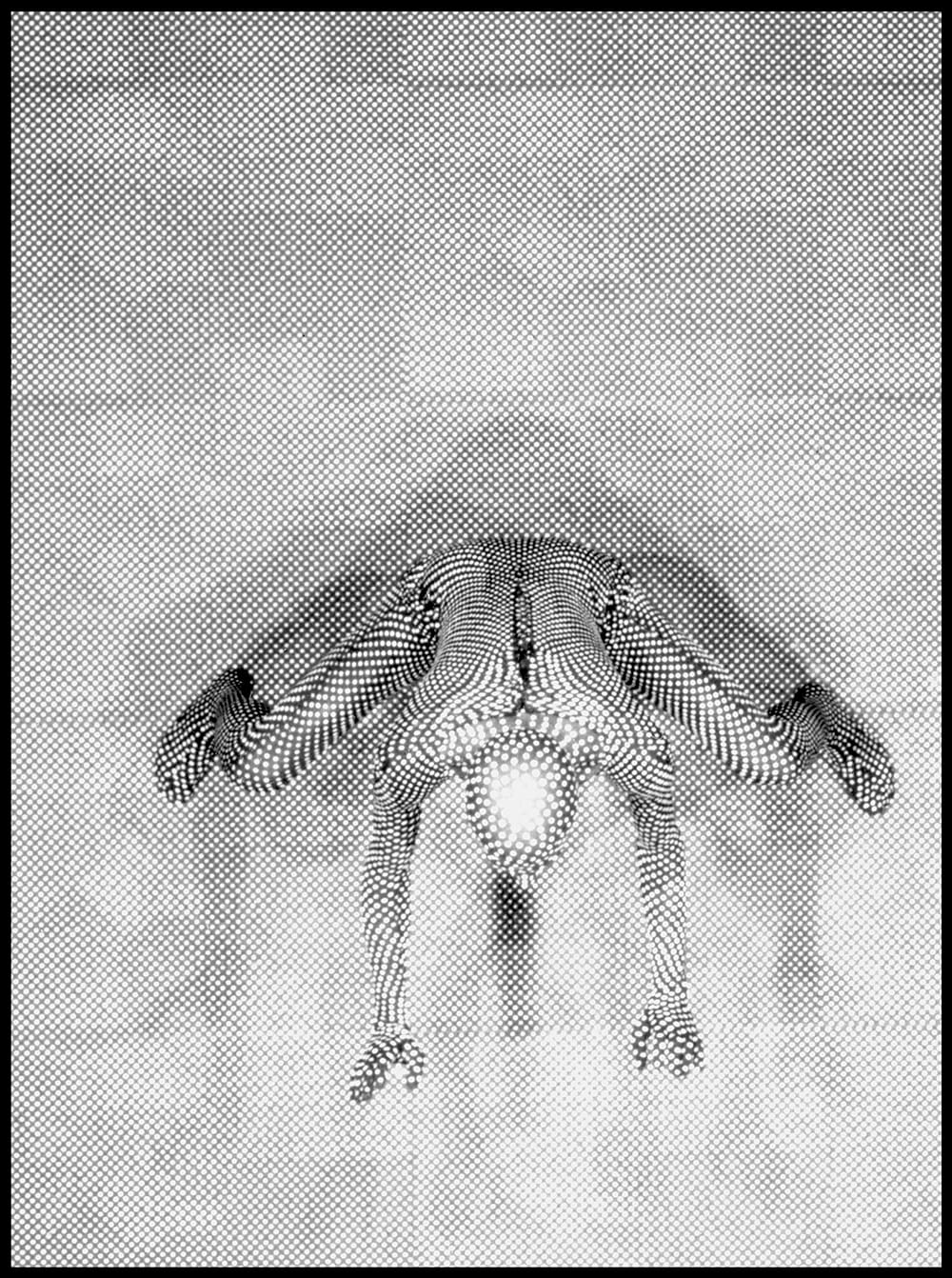

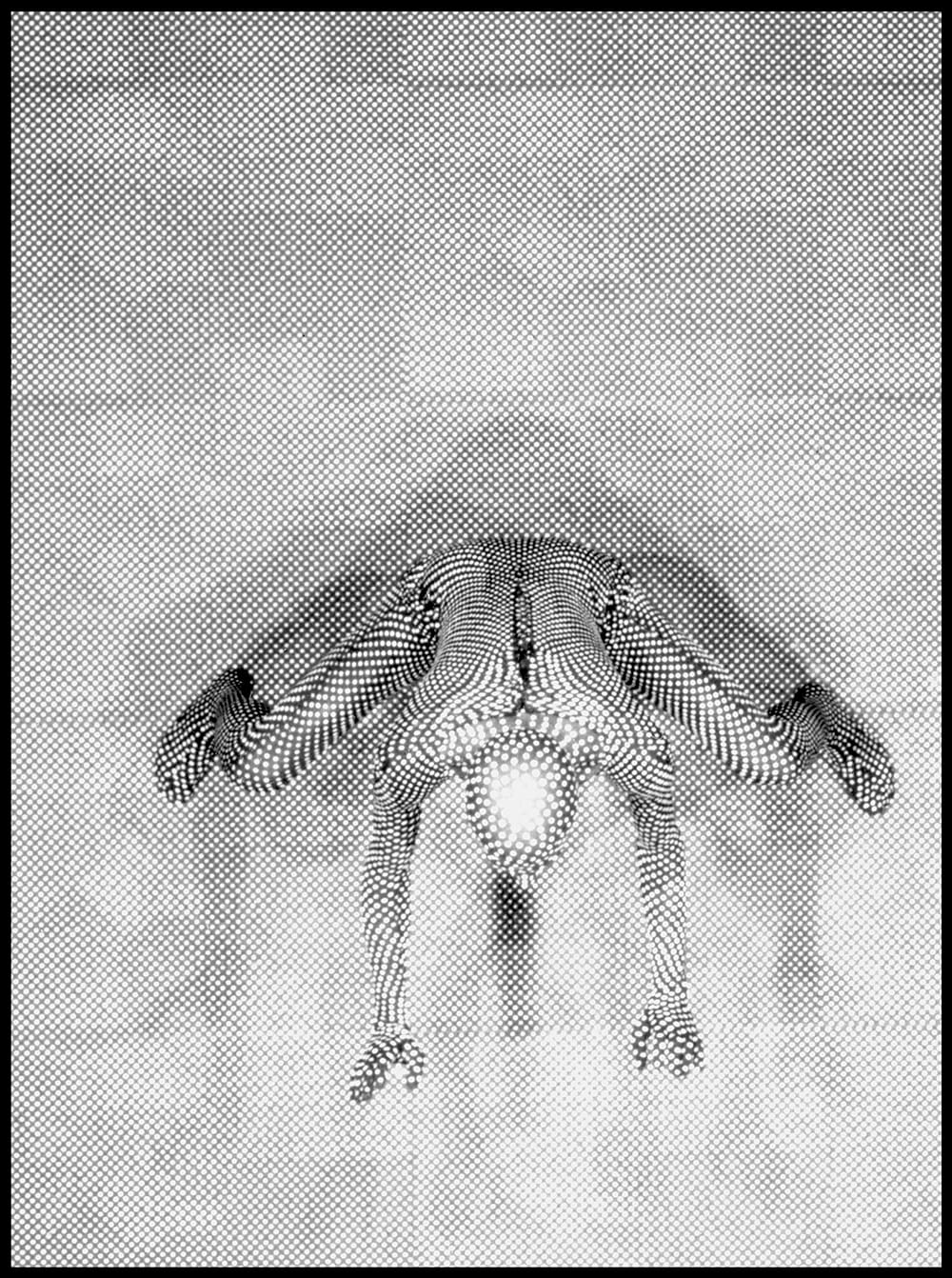

Throughout the fall and winter of 1967–68, Kubrick’s overcommitted collaborators conducted a last push to produce credible aliens worthy of their extraordinary film. If deemed successful, they would be seen at some stage during Bowman’s vault through Star Gate, or perhaps during the hotel room scene. This was never quite clear, and Kubrick may not have known himself. Just as the prehistoric protohumans at the Dawn of Man couldn’t look like men stuffed into ape suits, 2001’s extraterrestrials couldn’t look like that dreaded cliché, the Little Green Men. In one of the production’s more bizarre episodes, in September 1967 Kubrick asked Stuart Freeborn to transform Dan Richter into an eerily pointillist creature soon dubbed “Polka Dot Man.”

Discussions between Stanley and Christiane concerning what extraterrestrials might look like were ongoing throughout the production, and led eventually to her late-breaking effort with Charleen Pederson to create them in sculptural form. “I said, ‘Have you ever seen a good alien in a film?’ ” she remembered. “ ‘No.’ ‘Can you make one up?’ ‘No.’ I did hundreds of drawings of aliens. They’d look like . . . drawings of aliens. Ugh!”

Their debate was typically exhaustive. “You can go way out and go so far as to make it into bacteria . . . or a veil of gas,” said Christiane. At this, she remembered her husband replying, “Yeah, all right, but that’s not interesting. We don’t want to watch a veil of gas.” And continuing: “That’s one interesting thing about aliens. We can’t satisfy our imagination, and there’s nothing that would [make you] think, ‘Oh yeah, it’s probably like that.’ No, nothing comes to mind that would astonish you beyond everything. Okay, maybe it’s on a planet where the gravity is so much that anything can only exist in a gazillionth of a millimeter of gas. Or it’s a bird that flies through the air like a stone and smashes everything up—right, okay—or gases or chemicals or bacteria or . . . You know, you go through certain kinds of cells, certain kinds of brain waves that form things.”

He worked the problem rhetorically first, in other words. “He said, ‘I can’t come up with anything that wouldn’t bore me to death,’ ” Christiane recalled. “And the minute you name it, you’re already bored, the minute you draw it, the minute you . . . I mean, you can do it comical, that’s funny; you can do it beautiful, nice; you know, you can do wonderful, magical things, but it isn’t satisfying. What would truly astonish you if you saw an alien? What would it have to be? We don’t know, they always fail big-time. I’ve never seen an alien in a film, or in a book, or in a drawing, or in a description, that made me think, ‘Oh yeah, that must be like it.’ ”

Asked if she was remembering her own thoughts or what Stanley had said, Christiane replied, “We both did. And we talked to Arthur about it a lot. That this is all very frustrating, because our imagination just isn’t interesting. The minute we can imagine it, by that token, it loses the charm or interest.”

Still, Kubrick wasn’t a theorist, he was one of the century’s great practitioners, and he wanted to try. He’d kept Dan Richter on the payroll not in friendship—though that may have been part of it—but because he recognized the man’s abilities. If anyone could become an extraterrestrial, it was this diminutive, sui generis character who had not only successfully incarnated Australopithecus africanus but also had brought an entire tribe of them to gibbering, gesticulating life.

That achievement had required Stuart Freeborn’s rather considerable help, too, of course, and in late August Kubrick tromped up the stairs to the makeup man’s sunny workshop. Aliens were already a lively topic of discussion at Borehamwood, and the subject needed no introduction. “I’ve got an idea about this,” the director said. “We can do it, not necessarily optically, but . . .” He proceeded to outline a process involving a form of optical illusionism. “He said, ‘What I figure is this,’ ” Freeborn remembered. “He’d seen a dotted pattern somewhere, in front of a dotted-pattern background, and the result was something that was virtually invisible yet somewhat visible just because it was on a different plane than the background. It was an intriguing idea, and Stanley asked me to begin working on something along those lines.”

Kubrick huddled with Richter as well. “I want to shoot some footage of aliens,” he said.

“How could I help with that, Stanley?”

“Do you know what high-contrast film is?”

“Not really.”

“Well, it’s black-and-white film with no grey scale. Everything is either black or white. What I want to do is paint you white and then cover you with polka dots. Then I want to put you in front of a white background with black polka dots and shoot you in high-con. If you’re still, the screen should be filled with stationary points and you should be invisible. What I want to see is if, when you move, the dots become an image of an alien. Then I can reverse the color, and I will have created an alien out of dots of light.”

Reflecting on the man’s tenacity, Richter wrote, “I have come to realize that I cannot judge him by the measure I apply to other men and women. What would be compulsion in others is single-mindedness in Stanley.” By the winter of 1967–68, four years had passed since Kubrick’s first meeting with Clarke, and the clean-shaven kid with the successful Cold War satire had morphed into a bearded figure with fatigue lurking about the eyes. (A beard that in Clarke’s estimation made him look “like a slightly cynical rabbi”—a line that Kubrick, who’d experienced overt anti-Semitism in Hollywood and was uncomfortable drawing attention to his ethnicity, crossed out when censoring the author’s unpublished Life magazine profile.) A contrarian to the end, the director may still have been reacting to Carl Sagan’s suggestion that 2001’s aliens should be hinted at but not shown. More likely, Sagan’s views had been forgotten as he wrestled with the challenge of presenting . . . something. A creature just weird enough, and different enough, and powerful enough that he, or she, or it didn’t risk taking the air out of the whole enterprise.

Accordingly, Freeborn made a bald cap to fit Richter “nice and tight,” painted it white, found the biggest paper punch in England, and used it to “stamp out perfect rounds of black paper.” He fitted Dan with a pair of form-fitting shorts and made him up in white all over. In some kind of weird premonitory riff on a putative Area 51 medical procedure, his assistant methodically handed him little round dots of black paper with tweezers, and Freeborn dabbed each with glue and pasted it on Richter.

And we went all over his body, and it gave an incredible appearance—stunning. We covered him completely—right over his feet, all down his legs, everywhere. Then we stood him against a background with the same-size black dots all over it. The effect was stunning. Standing still, he would disappear into the backing; but when he moved, you could just make out a shape. It was an amazingly weird effect—quite extraordinary—but I don’t think it really fit in the movie. I could never see how Stanley was going to use it, and, of course, he never did. But it was quite phenomenal.

Reflecting on this last phase of his work on 2001, Freeborn continued, “I think it was too good, in a way, but it wasn’t really getting to what he wanted. Because an alien is—what?”

That was indeed the question, and Trumbull also became embroiled in these attempts, which expanded within his workshop to encompass strange levitating slit scan cityscapes. With the sleet of his third winter in England pounding on the studio roof, Trumbull constructed circles, squares, and hexagons of tiny lightbulbs, which could be switched on and off in sequence while the camera went past, and used them to create ostensibly extraterrestrial architectonic forms. “And so a flat bunch of lights would become a huge streak, like a building, a floating building with no top or bottom,” he recalled. “It’d be big in the middle and taper down as the lights switched . . . It was really quite beautiful. I shot some really interesting tests of these floating cities of light.”

Dan Richter, transformed from Moonwatcher to Polka Dot Man.

Trumbull’s efforts to create aliens were also composed of translucent, floating light patterns. “I made this really interesting little slit scan machine that was a kaleidoscope projector of two mirrors and a little rotating piece of artwork under the mirrors,” he recalled. When turned, the artwork “actually created a humanoid shape, like a head, shoulders, arms, and a body and two legs of pure light, just by the patterns . . . And I got pretty far along on that, and I actually got some beautiful-looking stuff, but we were literally two weeks from having to shut down, and Kubrick said, ‘You’ve just got to stop. There’s no way. Even if you succeeded with this, I can’t cut it into the movie anymore.’ ”

In the end, the question of producing an unbelievably believable extraterrestrial, or maybe a believably unbelievable one, had a cat-chasing-its-own-tail quality. “If it’s so surreal and so crazy that it’s unique, then it doesn’t work as an astonishment or a scare,” Christiane observed. “We have to relate it to something. And if we relate it to something, then it’s no longer original.”

She remembered Stanley concluding the whole effort with resigned humility. “It would be great if I could think of something that took everybody apart; something that absolutely would cause people to gasp,” he told her sadly. “I wish I was talented and I could think of something, but I can’t. The monolith leaves that open void that we feel when we try to imagine that which is unimaginable.”

• • •

As of late November 1967, Kubrick had chosen music for all of the film’s key sequences, but officially, at least, they were “temp tracks”—meaning they were holding space for original new compositions. The director himself referred to them in that way. Few big Hollywood films, let alone hugely expensive Cinerama road-show productions, had been released without an original score. New music was considered crucial to hyping these productions as major cultural events, and thus an important component of any promotional strategy.

By now, 2001 was a good $6 million over budget and years overdue. With MGM having piled an inordinate stack of chips on Kubrick’s vision, Roger Caras and Louis Blau had spent much of 1966 and 1967 fending off quietly furious accusations from studio executives that the director’s actions—and specifically, his strict security lockdown—were severely hampering their ability to protect their investment. Certainly MGM viewed an original score as part of that protection. So Kubrick wasn’t in a good position to argue that his temp tracks could easily be converted into permanent ones simply by clearing the rights.

Much of the pressure the studio exerted on him during the last phases of 2001’s production remains opaque, but nobody who worked with him doubted that it existed and was consequential. Close collaborators such as Doug Trumbull noted with appreciation that Kubrick functioned as a kind of firewall, never transmitting the heat to his subordinates, even as he grew more preoccupied and less lighthearted.

Certainly MGM president Robert O’Brien absorbed significant in-house and shareholder disquiet over Kubrick’s expanding costs and ever-deferred delivery dates. In effect, he ran interference. A well-read and charismatic figure, O’Brien was conspicuously active with liberal causes and a friend of the Kennedy family. Born in 1904, he emerged from rural poverty in Montana, graduated from the University of Chicago Law School in 1933, and was appointed a commissioner at the Securities and Exchange Commission by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

O’Brien’s lifelong interest in films then prompted him to switch careers, and in 1944 he became a special assistant to the president of Paramount Pictures, ultimately moving to MGM’s parent company Loews in 1957. On ascending to the position of studio president in 1962, he quickly earned a reputation for unflinching loyalty to the directors he championed.

Kubrick’s project wasn’t the first time that he’d put the studio’s future on the line in standing by a film. David Lean’s three-hour epic Doctor Zhivago, released in 1965, more than doubled its original budget, with production costs ballooning from $7 to $15 million during ten months of arduous production in Spain and Finland. No expense was spared as nearly a thousand men labored for a half year to build sprawling sets across ten acres of studio ground near Madrid. With wintry Moscow rising improbably on the Iberian Peninsula, O’Brien quelled internal dissent and ensured that the studio provided Lean with the tools he required to realize his vision. And the gamble paid off: a huge, crowd-pleasing hit, Doctor Zhivago grossed $112 million in its initial release.

While this success certainly helped O’Brien hold the line for Kubrick, other senior studio executives weren’t so sanguine, and neither were the shareholders. As MGM dipped repeatedly into the red, Chicago real estate tycoon Philip Levin—who owned more than five hundred thousand shares in the company, or about 10 percent—waged two expensive proxy fights attempting to oust the MGM president while 2001 was in production, one in 1966 and the other the following year. While Levin’s moves weren’t necessarily tied to a specific film—rather, they concerned O’Brien’s overall business strategy—there’s no doubt that Kubrick’s project had caused a profound sense of disquiet among those invested in the company. “They were very nervous—quite rightly,” Christiane remembered. “If I had that much money floating around, and somebody’s promising me something and I see nothing, and he has the arrogance to say, ‘No, I don’t want you to look’ . . . They were really very gracious in taking this shit from him.”

Although Kubrick had a well-deserved—and fiercely protected—reputation for sovereign creative decision making, he relied on MGM to keep the lights on, and as a result, he wasn’t immune to persuasion. In particular, he was attentive to views expressed by O’Brien, whose commitment to his production had proven unshakable and whose future at the studio had become increasingly contingent on 2001’s success. All of these factors certainly colored his decision in late November to call one of Hollywood’s leading film composers, Alex North.

Film music producer Robert Townson has stated that Kubrick’s call, in which he offered North the job of scoring 2001, came at MGM’s suggestion and followed the director’s proposal that his temp tracks simply be cleared and used. Kubrick had already worked with North, who did the score for Spartacus in 1960, and the composer’s reputation had only grown since due to his well-received scores for Cleopatra (1963) and The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965). Initially “ecstatic at the chance to work with Kubrick again,” North was particularly happy to discover that the film had only twenty-five minutes of dialogue—something he fondly imagined would give him unprecedented freedom.

He was soon disabused of this notion, however, on flying to London in early December and discovering that Kubrick fully intended to keep some of his “temporary” tracks and wanted him to work around them. After watching the film’s first hour with its temp tracks laid in, North said he “couldn’t accept the idea of composing part of the score interpolated with other composers. I felt I could compose music that had the ingredients and essence of what Kubrick wanted and give it a consistency and homogeneity and contemporary feel.” Reluctantly, Kubrick agreed—thereafter seemingly expecting the composer to emulate and even improve on the existing music.

North knew he was in a difficult position. He’d be competing with some of the top masterworks in the Western canon. Nevertheless, by mid-December a deal had been made. MGM would pay him $25,000 plus expenses and accommodations. A ninety-one-piece orchestra was booked, and orchestrator Henry Brant, who’d orchestrated composer Alec Templeton’s “Bach Goes to Town” for Benny Goodman in 1939, and who’d worked with North most recently on the Cleopatra score, was hired to do the arrangements. Recording sessions were scheduled for January 15 and 16, and North flew back to London with his wife, Anna Höllger-North, on Christmas Eve. “Alex was treated like a king,” she remembered in 1998. “We were given an apartment, a cook, and a car, and he and Henry Brant went straight to work, realizing that Kubrick had gotten used to these temp tracks and that something similar had to be manufactured.”

Brant remembered North telling him that Kubrick had said during their December meeting that if he’d been able to get permissions for his temp tracks, 2001’s soundtrack would have been a “fait accompli.” (Whether “permissions” in this context signified the clearing of rights or agreement from MGM to use the tracks in the first place remains unclear, though evidence points to the latter.) In any case, North was plagued throughout by the unsettling sense that nothing he could compose would truly compete with the two Strausses and Ligeti. Laboring under a great deal of psychological pressure, he prepared a major set of new compositions in a remarkably short period of time. “I worked day and night to meet the first recording date, but with the stress and strain, I came down with muscle spasms and back trouble,” he remembered.

It all came to a head just prior to the recording sessions, when North experienced an incapacitating physical collapse. Looking down at the gathering orchestra at Denham Film Studios on the morning of January 15, 1968, de Wilde and Kubrick were shocked to see the composer being wheeled in on a stretcher. “He came in an ambulance,” de Wilde recalled. “Stanley and myself were flabbergasted.” With North compos mentis but horizontal, Henry Brant conducted, and the session proceeded.

Throughout the two days of recording, Kubrick came and went, sometimes providing comments to Brant, sometimes to North. “I was present at all the recording sessions, Kubrick was very pleased and very complimentary, and there was no friction,” said Höllger-North. Her husband had a similar sense of the proceedings. “He made some very good suggestions, musically,” he recalled. “I assumed all was going well, what with his participation and interest in the recording.”

De Wilde read Kubrick’s reactions somewhat differently. “He looked at me, and I looked at him, and it was obvious it was never going to go anywhere,” he said. Brant also understood that all was not well. He recalled the director listening to the opening movements of North’s composition—probably the part written to supplant Strauss’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra—and commenting, “It’s a marvelous piece of music, a beautiful piece, but it doesn’t suit my picture.” One of the orchestrator’s score annotations tells the story even more clearly: “Stanley hates this, but I like it!” Completing that trajectory, Con Pederson remembered Kubrick returning to Borehamwood with a curtly dismissive, “It’s shit.”

Nevertheless, after two days, more than forty minutes of new music had been recorded, and North withdrew to his apartment to rest and wait for the second and third parts of the film to be completed so that he could continue. More than a week passed without further word from the director, however, and he found he couldn’t reach him directly, instead passing messages via an assistant. He assured Kubrick that his physical duress had been momentary, that he was completely willing to proceed, and that he was working under a doctor’s care. Finally, he received word back: no further music would be required. The rest of the film would “use breathing effects.”

North’s scribbled notes, prepared before calling his agent in mid-January, read like a bulletin from a crisis: “Fulfilled my obligation—recorded over 40 minutes music—delaying me—liked stuff, then changed his mind.” They record his assessment of Kubrick’s intentions: “clearing rights to temp tracks . . . psychological hang-up.” The composer also evidently instructed his agent to contact Robert O’Brien and bring pressure to bear.

Years later, Kubrick confirmed that North’s agent had, in fact, called O’Brien “to warn him that if I didn’t use his client’s score, the film would not make its premiere date. But in that instance, as in all others, O’Brien trusted my judgment. He is a wonderful man, and one of the very few film bosses who was able to inspire genuine loyalty and affection from his filmmakers.” In comments made to French film critic Michel Ciment, Kubrick gave an unsparing assessment of North’s work.

Although he and I went over the picture very carefully, and he listened to these temporary tracks (Strauss, Ligeti, Khachaturian) and agreed that they worked fine and would serve as a guide for the musical objectives of each sequence he, nevertheless, wrote and recorded a score which could not have been more alien to the music we had listened to, and, much more serious than that, a score which, in my opinion, was completely inadequate for the film. With the premiere looming up, I had no time left to even think about another score being written, and had I not been able to use the music I had already selected for the temporary tracks, I don’t know what I would have done.

Was this disingenuous? Höllger-North clearly felt it had been Kubrick’s plan from the start. “All along, he was trying to clear the rights to the temp track music, so he really under pretext had Alex compose the score, and I always thought that was unfair,” she charged. “Kubrick managed to clear the rights, and Alex was never told that. We went to see 2001 in New York and were very surprised when Alex’s music—not a note of it was in the film.”

A story from January 1968 undermines her assessment, however. On arrival for one of their late-night talks, Cantwell found Kubrick uncharacteristically despondent. As they assembled sandwiches, “something was on his mind,” he remembered. “We just let the silence be there, and then he said he had a problem. He said, ‘I just had to fire my fourth composer. I’m starting from scratch. Back to square one.’ And ‘What to do, and who to consider, in the time we’ve got left.’ By then, of course, I was totally identifying with the scale of what he was trying to do. He said, ‘I’m even thinking, should I contact the Beatles?’ ”

At this question—rhetorically phrased but clearly offered for serious consideration—Cantwell “absorbed that for a little while and just gave him my straight feelings that ‘No, that wouldn’t be worthy.’ ”

There’s no reason to suppose Kubrick’s Beatles idea was anything more than a fleeting straw clutched at momentarily. In any case, Cantwell was struck by the gravity of the situation. “The one thing Stanley communicated to me was a deep disappointment,” he said. “For Stanley, that was not something to be devastated by; it had to be resolved, it couldn’t diminish the film. And it was this mix of sadness, the urgency, the regret, the adrenaline of ‘What’s the course from here?’ All of that [was] wrapped in. He communicated very quietly so much of the intensity of his feelings.”

• • •

In his ongoing quest to improve the Star Gate sequence, Kubrick decided in September that he needed additional aerial footage to augment the material Birkin had shot in Scotland the previous year. He contacted cinematographer Bob Gaffney, who flew to London on September 27, arriving in Borehamwood just in time to witness the director filming bones spinning through the back-lot air. So far, Gaffney’s contribution to 2001 had been persuading Kubrick to use 65-millimeter Cinerama stock rather than another, less sensational wide-screen film format back in 1964. Now the director took him into his office and pulled an illustrated book of southwestern desert landscapes from the shelf. “I want scenes in Monument Valley that are shot in very low light, flying over the monument and the terrain as low as you can go,” he said. Asked what kind of sequence it was for, Kubrick was characteristically cagey.

By October 10, Gaffney was already in place near Page, Arizona, with a rented Panaflex and plenty of film. He’d decided that a Cessna light aircraft would provide a better shooting platform than a helicopter, and he jury-rigged a camera mount under the wing to get the lens away from the propeller. After several days of filming rugged canyon walls and mesas near Page, he shifted his attention due east to Monument Valley—among the most filmed landscapes in the United States, and practically synonymous with the American West.

Birkin and pilot Bernard Mayer had already courted disaster flying their chopper into the downdrafts and unpredictable wind shears of Scotland the previous November. Gaffney and his pilot had located a dirt strip directly beside a Texaco station not far from the valley, with a motel fortuitously positioned directly across the street. Mules and goats wandered untethered around the area. As with the Dawn of Man stills, their instructions were to film only at dawn or near sunset. Late on the first afternoon, Gaffney loaded the camera, noted that the wind sock was “deader than a doornail,” and they took off before sunset in a whirl of dust.

As soon as they cleared the top of the nearest mesa, however, the plane got slammed by a hundred-mile-an-hour wind, which threw its nose higher in the air. Corkscrewing upward and verging on a stall, the pilot wrestled with the shuddering stick and screamed, “I knew you were going to get me killed one of these days, you stupid son of a bitch!”

“Push the stick down, or I will!” Gaffney shouted back, reaching over to help him wrestle it forward. The Cessna dove below the desert jet stream to calmer air. After leveling out, they turned back to where they’d taken off and saw with a new wave of adrenaline that the cloud they’d made was still hanging densely in the air, obscuring their view. There was no wind here, but the setting sun was directly behind the strip, turning the dust into an opaque wall. “You fly, I’ll be the radar,” Gaffney said, leaning forward and squinting through the windscreen as they made their approach. “Two degrees left . . . Right . . . Let the prop down . . . Chop the power!” And with a boom, they slammed down onto the runway, blowing a tire in the process.

They’d made it.

Having lived to tell the tale, they figured out strategies to dodge the wind, and several of their aerial views were subsequently transformed via Purple Hearts processing into vivid shades of maroon, umber, green, and blue, and then edited into the Star Gate sequence. In one, Monument Valley’s characteristic sandstone spires are clearly evident. “I almost got killed,” the cameraman recalled somberly to Kubrick biographer Vincent LoBrutto in 1997.

A few years after 2001’s release, Birkin was helping Kubrick research another project and mentioned his regret that one of his Scotland shots—of the summit of Ben Nevis, with its abandoned meteorological station—was perhaps a bit too recognizable in the film. The director replied that in retrospect he probably shouldn’t have used some of Gaffney’s footage for the same reason.

• • •

Kubrick edited 2001: A Space Odyssey from October 9, 1967, until March 6, 1968—the day before boarding the Queen Elizabeth bound for New York. By most accounts, he did the cutting himself, with Ray Lovejoy, officially the film’s editor, assisting, and David de Wilde coming and going with fresh prints, sound rolls, and cans of film.

Colin Cantwell, who witnessed some of the edit, recalled that the film’s structure already existed in Kubrick’s head and that in a masterly performance, it was executed in linear fashion—a serial process from beginning to end, with no recutting attempted. The director simply went reel by reel, editing each section complete with the sound and music, and then sent it off immediately—an accelerated schedule necessary so that the time-consuming procedure could start of converting the film to 35 millimeter for general release in late 1968, following its 70-millimeter Cinerama run.

As a result of this imperative, Kubrick had no latitude for error and didn’t have the luxury of going back to tweak earlier scenes as he proceeded. The entire picture had to be clearly visualized, with anything that needed echoing from the first reel accounted for in advance, and a comprehensive picture of what the last reel should look like well in mind as he edited the opening sequences. “That was as bold as anything else in the film, and as perfectly executed,” Cantwell marvelled.

Despite such constraints—which seemingly disallowed any rethinking, let alone test screenings—“we just had a good time,” de Wilde remembered. “It was a bit of fun. It was very relaxed by then, and we were all relaxed. They’d got it in the can.”

Cantwell’s description would seem to indicate that the winnowing away of the film’s more expositional elements had been largely previsualized, with 2001 emerging reel by reel as the largely nonverbal work we know. And indeed, according to de Wilde, the documentary prologue that Roger Caras had labored over in 1966 was never edited, let alone cut into the opening of the film. But the record shows that Kubrick, in fact, continued struggling with the question of a narrative voice-over throughout the five-month editing period, abandoning the idea not once but twice. Meanwhile, throughout September, October, and into November, Clarke conscientiously transmitted revised blocks of narration to Borehamwood. His texts covered the Dawn of Man, HAL’s neurosis, and Discovery’s various features and operations, all rendered in semi-sententious documentary voice-over style.

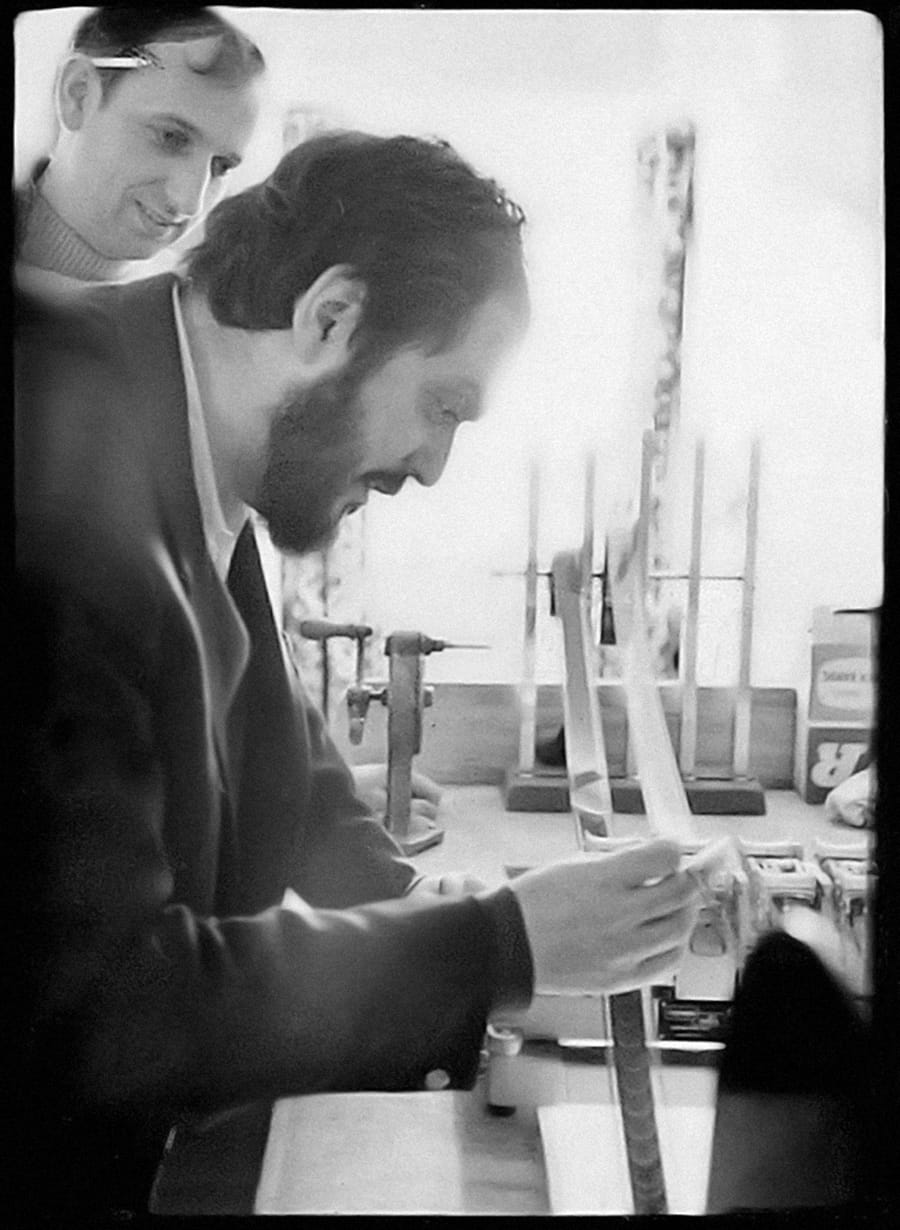

Kubrick working with assistant film editor David de Wilde.

Kubrick’s last big push to finalize the film’s narration unfolded in early November. Clarke was then on an American lecture tour, and his copy was either cabled directly to London or phoned in to unit publicist Benn Reyes in New York, who quickly forwarded it on to London. Snippets of his writing reveal how different 2001 would have been if they’d been used. For the Dawn of Man sequence: “They were children of the forest—gatherers of nuts and fruits and berries. But the forest was dying, defeated by centuries of drought, and they were dying with it. In this new world of open plains and stunted bushes, the search for food was an endless, losing battle.”

For Discovery: “Much of the time you spend inside a giant drum, slowly revolving so that centrifugal force gives you the feeling of normal weight. You can walk, exercise to keep fit, and prepare meals without the inconvenience of weightlessness.”

For HAL: “Since consciousness had first dawned for the computer, all of its great powers and skills had been directed to achieving perfection. Undistracted by the passions of life, it pursued this with absolute single-mindedness. But now for millions of lonely miles, it had been brooding over the secret it could not share, and the deception it had been made part of, and it was beginning to experience a profound sense of imperfection, of wrongness. For like his makers, Hal had been created innocent.”

While Kubrick’s decision in late November to use Rain for HAL’s voice was prompted largely by his dislike of Martin Balsam’s line readings, some of it may have been due to a growing unease over the effect such expositions would have on the film. A couple weeks before his sessions with the Canadian actor, this feeling had evidently crystallized, and from November 20 to the 22, Kubrick sent a flurry of cables attempting to reach Clarke on his tour. Stop work, he wrote, explaining tersely, “Narration needs drastically reduced.”

On the twenty-third, Clarke responded with an alarmed cable: “Just returned from two-week 10,000-mile lecture tour where I spent every spare minute working on narration as requested. Job will be completed in a few days, so very disturbed by your messages. Please clarify.” Kubrick’s answer that day was even more unequivocal: “Sorry about narration. As more film cut together, it became apparent narration was not needed.”

Clarke’s follow-up, a handwritten note from the Chelsea Hotel on the twenty-fifth, provides an interesting window into the author’s thinking. He was “rather upset,” he wrote, but he also referred to “some new purple prosery which it would be a pity to waste”—a revealing comment—and continued with an implicit admission: “I’ll be interested to see how you can possibly dispense with much of the narrative material, while at the same time I feel it’s a good thing if you can!”

By early December, Kubrick had reevaluated, however, and on the seventeenth he spoke to Clarke, who by then was in London, and said he wanted him to view the edited film in mid-January so that he could finish his voice-over texts. But when Clarke mentioned payment for the additional work—he asked for $5,000—Kubrick balked. “I must confess I’ve been under the impression that you have been paid to do the work on the screenplay and that this narration work is of a similar nature to the additional year and a half of my own work for which I have received no additional payment,” he wrote. (Italics in the original.)

At this, Clarke contained his exasperation with a mighty effort and fired off a message to Scott Meredith. Deploying the word “chutzpah,” he requested his agent not to “lean on him too hard, as I don’t want any unpleasantness or holdups on this last lap.” Kubrick’s argument might have resonated a bit better if he’d given Clarke a financial stake in the film three years before. In any case, he was clearly only going through the motions, and by January 23 he wrote the author again, now back in Ceylon: “It doesn’t look like we’ll get to the narration until mid-February. Scott has probably told you the $5,000 is okay. All goes well but desperately short of time—premiere Apr. 2 Wash D.C.”

Clarke soon responded that he was anxious to help, but cautioned, “It’s impossible to rush the sort of literary composition you’ll want—it has to be reworked over and over again, so as soon as you have anything finalized, I want to start thinking about it.” He added, however, that he could work from his existing drafts.

He never received Kubrick’s summons to London.

• • •

As Terry Southern discovered, few subjects were more fraught for Kubrick than the question of credit. Dan Richter remembers a discussion with the director near the end of his tenure at Borehamwood. Summoned for an audience in late September, he arrived to discover Kubrick standing and “pretending to look busy” behind his desk but “obviously nervous about something.” After a detour into an unrelated matter—one that Dan sensed immediately wasn’t the reason for their meeting—there was an uncomfortable pause. Which Richter broke. “What’s the matter, Stanley?” he asked.

“Well, Dan, I have to settle your credit with you, and I’ve got a problem.”

“What’s the problem? I’m the choreographer of the Dawn of Man.”

“Well, I can only give you one credit. So I want to give you the fourth starring credit. You can have that or the choreography credit, but you can’t have both.”

Evaluating the statement, Richter asked why.

“Well, Dan, that would give you more than one credit. And I’m the only one with more than one credit. So you’ll have to decide.”

Despite playing Moonwatcher, it hadn’t occurred to Dan that he might receive star billing. He’d always seen himself as the choreographer. He decided to make an awkward situation easier. “Well, I’ll take the starring credit,” he said. “Everybody knows I did the Dawn of Man choreography.”

“That’s what I thought you’d say,” Kubrick replied. But he still looked anxious. “Can you live with that?” he asked.

“Believe me, Stanley, I like the idea of being a star,” said Richter.

They stood and solemnly shook hands. And Richter’s name appears directly after Dullea, Lockwood, and Sylvester on 2001’s credit roll, appropriately enough.

Asked, decades later, what he thought Kubrick might have said if his answer had been that he deserved both credits and had worked extremely hard for them, Richter replied without hesitation, “He wouldn’t have given it to me.”

• • •

Doug Trumbull remembers 2001’s end game ambivalently, as a time of fatigue, low morale, and bitter feelings. Rivalries and tensions that had been implicit were becoming explicit, as they sometimes do when people are worn out and something significant is palpably ending. “Everybody was departing the movie like rats from a sinking ship, because everyone was so exhausted, just completely wiped out and tired of it, and their careers had been stalled,” Trumbull said. Work on 2001 had taken much longer than anyone had expected, and “they couldn’t get jobs on other movies. They were pissed off . . . They didn’t really realize what they had just been involved in—which I did.”

Nevertheless, his relationship with Kubrick was deteriorating. Trumbull knew how crucial he’d become to the making of 2001, and he was proud of it. Apart from his slit scans, he’d built and managed the film’s animation department after Wally Gentleman’s departure, among other contributions. Trumbull’s importance to the film can be judged by something Christiane told him when she ran into him at a film festival years after Stanley’s death. According to Trumbull, Christiane recalled asking her husband during the last phase of 2001’s production if he was worried about getting the film done. The director’s response had been, “No, I’m not worried because I have Doug.”

Despite this, and although he was now senior staff, Trumbull’s salary was frozen at the level it had been two years before. Chafing at this injustice—his peers were making much more than him—he agitated for a raise. But Kubrick, acutely aware that he was way over budget and that others might make the same argument, flatly refused. “That was one of the biggest challenges between me and Kubrick,” Trumbull remembered. “He just always said, ‘No.’ Utterly inflexible.”

Then as his March trip to New York and Los Angeles approached, the director decided he wanted to patent Trumbull’s slit scan machine. Its designer objected. “I was extremely averse to this idea because . . .” Trumbull hesitated. “I was just a kid. I didn’t know at the time that the employer actually does have the right to patent the work of his employees.” Kubrick told Trumbull that he’d hired people to write the patent claim.

“Hey, Stanley, do whatever you want, but I’m not going to help these people,” Trumbull replied.

“Well, I’m going to do it anyway.”

“Okay, do it. Just do it on your own.”