SPRING 1968–SPRING 2008

Two possibilities exist: either we’re alone in the universe, or we’re not. Both are equally terrifying.

—ARTHUR C. CLARKE

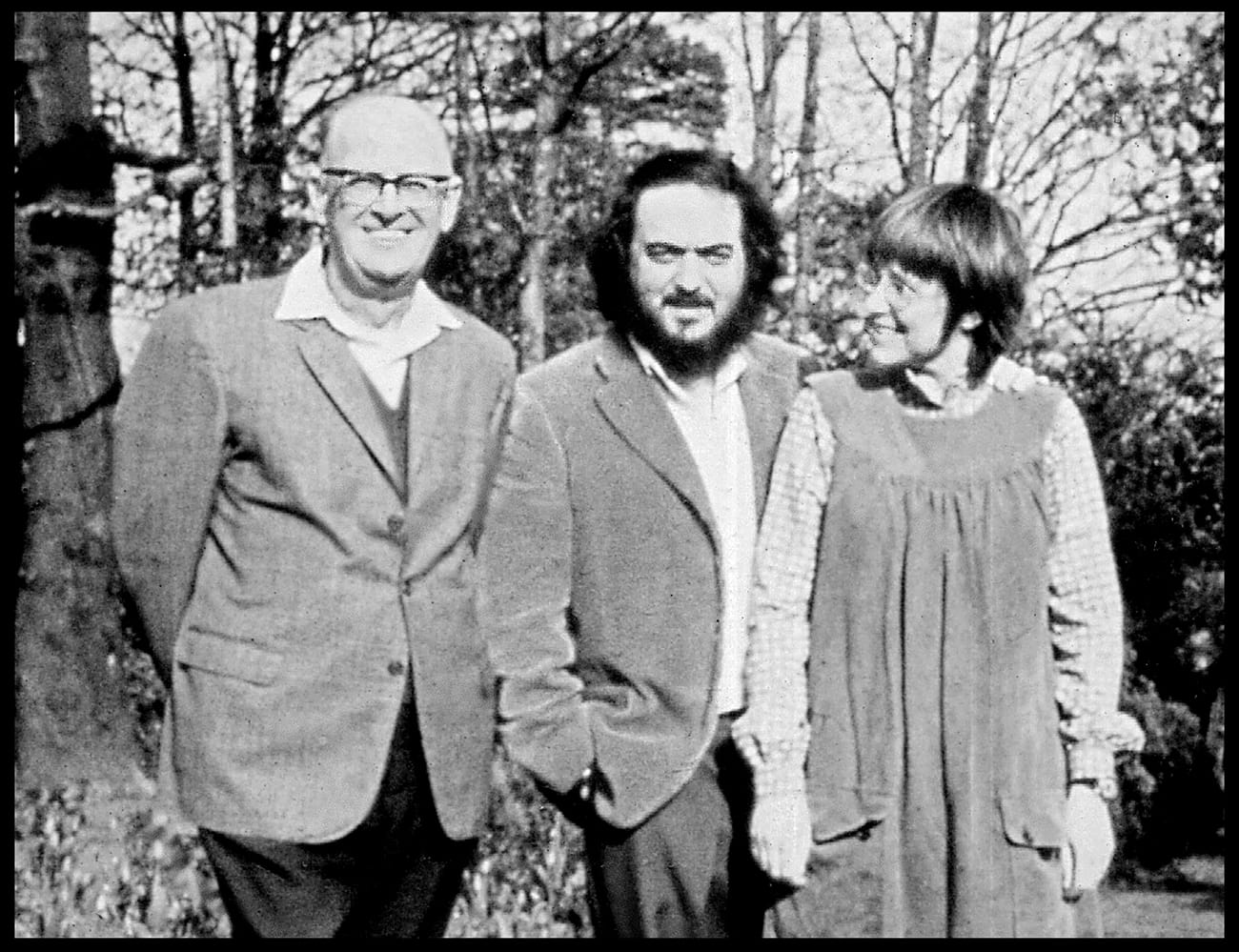

Many decades later, when he was relegated to a wheelchair and rarely left his adopted country, now called Sri Lanka, Arthur Clarke saw a photograph of Stanley Kubrick on his TV and was deeply moved. The author was seated in his study on the second floor of his spacious house in Colombo, watching a taped documentary about his old collaborator. The photograph appeared quite suddenly. In it, Kubrick was sitting on the floor in front of his own television in Childwickbury Manor—the sprawling eighteenth-century estate house with acres of surrounding greenery he’d purchased in 1977—and holding a microphone up to the screen.

At first glance, this mirroring and sense of remove might seem to evoke the distanced, screen-based world the two of them had conjured into being between 1964 and 1968 in 2001: A Space Odyssey—one in which human interactions occur across vast, echoing, alienating gulfs of space and time. But for Clarke, the sudden appearance of that televised photograph inverted any sense of remove, bringing a decisive friendship—and certainly the most important professional relationship in his life—crashing back into the room without warning.

It’s not surprising that the photo produced an upwelling of emotion in the writer. Apart from providing another example of the director’s familiar intensity—Kubrick’s lifelong determination to absorb and record everything important, without missing an implication or word—it revealed that his microphone was, in fact, recording none other than his old ally and intellectual sparring partner Arthur Clarke, who, in turn, was being featured in a BBC documentary.

“In those days, you couldn’t record television very easily, and so he sat there throughout the film,” Christiane recalled of her husband, who was most likely recording a 1979 broadcast of Time out of Mind, a program focusing on science fiction. “Stanley really admired Arthur and valued his opinions on everything and had great respect for him.”

A scene, then, of an aging science fiction writer watching a screen, seeing an aging film director also watching a screen and recording that writer’s every word. Taking it all in, Clarke blinked owlishly behind his glasses several times and burst into tears.

• • •

Finally published four months after the film’s release, Clarke’s novel was dedicated “To Stanley” and became an instant bestseller. Although he went out of his way to stress that his version of their mutually conceived narrative didn’t necessarily reflect Kubrick’s views, the book quickly became a kind of code breaker’s handbook, pored over by baffled viewers who attempted to decipher 2001’s cryptic meanings.

One of Clarke’s early comments following the film’s Washington premiere was, “If anyone understands it on the first viewing, we’ve failed in our intention.” Given what we know of his own initial reaction, it was his way of making lemonade. Kubrick quickly expressed his disapproval. “I don’t agree with that statement of Arthur’s, and I believe he said it facetiously,” he said that September. There followed an exchange in the media, with Clarke standing by his remark and pointing out that it didn’t mean you couldn’t enjoy 2001, only that it rewarded repeated viewings. In any case, following the novel’s July 1968 release, his new sound bite for confused viewers was “read the book, see the film, and repeat the dose as often as necessary.”

The box office remained extraordinary, and 2001 became the highest-grossing film of the year—the only Kubrick picture ever to achieve such a standing. That June, Clarke wrote his friend Ray Bradbury, who’d written a negative review of 2001, urging him to see the second cut. Commenting on the ticket sales, Clarke observed, “Stanley is now laughing all the way to the bank.” The following year, he amended this in an interview to “Stanley and I are laughing all the way to the bank.” By then, the novel was manifestly helping his bottom line as well, evidently to considerable merriment. The lemonade had become lucrative.

A decade later, Clarke was disarmingly candid about what his expectations had been following the film’s disastrous initial screenings. “The success of 2001 was a great surprise to me,” he told a BBC journalist, probably in the very program that his collaborator would later record with a handheld microphone, “and I suspect to Stanley Kubrick as well.”

Of course, we hoped it would be successful, but we never imagined it would become a cult movie and have such tremendous sustaining power. It may have had something to do with the timing. It came out just before the first Apollo flight around the Moon—Apollo 8; the Christmas flight in 1968—and then, of course, the landing on the Moon in July of 1969. But I don’t think the people who were interested in spaceflight as such were the ones who made up the audience of 2001, which included a large number of hippie types, and perhaps even people who were antagonistic to technology.

He wasn’t wrong. 2001 swept the entire sixties counterculture into theaters worldwide, inspiring raves from some of its leading figures. Asked about the film in 1968, Beatle John Lennon quipped, “2001? I see it every week.” The following year, David Bowie released “Space Oddity,” the single that introduced his astronaut alter ego “Major Tom” to the world—a nod, clearly, to 2001. But, of course, everyone even remotely interested in spaceflight and technology went to see it as well.

When he’d had time to recover from his initial reaction, Clarke spoke candidly about the fate of his narrative voice-overs. “Stanley very wisely realized that using narration, although it might have made it simpler and clearer, would have been intolerable,” he told Joseph Gelmis, the Newsday critic who’d publicly reevaluated his own initial review. “It would have destroyed much of the mystery.”

Within a few weeks of the premiere, Clarke even found himself enjoying the heated debates engendered by 2001’s willful ambiguity, sometimes positioning himself near theater doors just to overhear them. “It’s creating more controversy than any movie I can think of,” he told a Berkeley radio station in May 1968. “I used to have great fun standing outside the theater and listening to the crowds, the people coming out and arguing all the way down Broadway . . . And this is fine. We want people to think, and not necessarily to think the way that we do.”

Asked if he felt the pervasive spread of technology was beginning to dehumanize us, Clarke replied, “No, I think it’s superhumanizing us.”

• • •

A half century later and almost two decades after its eponymous year, 2001’s influence remains so pervasive that it’s hard to overestimate. The film’s fusion of scientifically informed speculation, industrially supported design, technofuturism, and kaleidoscopic cinematic abstraction brought art and science together in ways never seen previously. 2001’s ongoing sway over design alone can be seen across filmmaking, advertising, and technology. Its impact on contemporary discourse includes the ubiquitous name checking of HAL in increasingly relevant and even alarming discussions of artificial intelligence. Richard Strauss’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra is forever associated with the film, so much so that it’s hard to consider it in isolation from Kubrick’s epochal opening sunrise over the Earth and Moon. Zarathustra has been used many times to reference 2001, including in Hal Ashby’s 1979 film Being There, in which Peter Sellers, playing the middle-aged simpleton Chauncey Gardiner, leaves his house for the first time while Brazilian composer Eumir Deodato’s Grammy-winning funk arrangement of the composition booms on the soundtrack. In late 2017, Todd Haynes revived Deodato’s version to similar effect in his film Wonderstruck.

Other recent references include overt tributes in various episodes of Mad Men, including one titled “The Monolith”; repeated riffs in Matt Groening’s animated series The Simpsons (in one episode, Bart threw a felt-tip marker in the air, which becomes a satellite); Tim Burton’s 2005 film Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, in which shots of Dan Richter and his capering man-apes were actually inserted into a scene (the monolith morphs into a chocolate bar, a bit too obviously); and an homage to 2001’s final sequence in Bill Pohlad’s moving 2014 docudrama about the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson, Love & Mercy. These and other examples attest to the film’s continuing power to affect contemporary culture—certainly one measure of a masterpiece.

Apart from such overt references, 2001’s epic validation of the science fiction genre stands at the wellspring of all the big-budget, effects-laden movies to follow. Just as Kubrick and Clarke had intuited in their opening conversations in New York, the film marked the end of the Western as the predominant Hollywood genre and its replacement by stories set in a more expansive new frontier. Among the first cinematic responses, ironically, was Russian master Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 film Solaris. Although he publicly disparaged 2001 in 1968, the wheel-shaped space station, disembodied alien intelligence, and metaphysical concerns of Solaris betray the clear influence of its predecessor—even if Tarkovsky intended his film as a kind of riposte. Worth watching and reasonably well received in the West, Solaris had its flaws, and the director himself later let it be known that in his view it was a failure—so he ultimately had problems with both 2001 and his own rejoinder.

In American filmmaking, 2001’s visual power and excellent box office gave an emphatic green light to Hollywood, which set about funding successor projects. From Close Encounters of the Third Kind to the Star Wars and Alien franchises—and ultimately such comparatively recent films as James Cameron’s Avatar and Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar—a series of landmark movies was influenced and enabled by Kubrick’s and Clarke’s achievement. Asked if a lightbulb ever went off that inspired him to become a filmmaker, Cameron, the director of the two highest-grossing movies ever made, was unequivocal.

The first one was when I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey for the first time. And the lightbulb there was, “You know, a movie can be more than just telling a story. It can be a piece of art.” It can be something that has a profound impact on your imagination, on your appreciation of how music works with the images. It sort of just blew the doors off the whole thing for me at the age of fourteen, and I started thinking about film in a completely different way and got fascinated by it.

For his part, Steven Spielberg has called 2001 “the big bang” that inspired his generation of directors. And in the late 1970s, George Lucas assumed a tone of humility when considering the film. 2001, he said, is the “ultimate science fiction movie,” continuing, “It is going to be very hard for someone to come along and make a better movie, as far as I’m concerned. On a technical level, [Star Wars] can be compared, but personally I think that 2001 is far superior.”

More recently, he grew almost tongue-tied when asked about 2001. “I’m not sure . . . I would have had the guts to do what Stanley did,” he said in the documentary Standing on the Shoulders of Kubrick: The Legacy of 2001. “I don’t know whether I—I’m trying to get up the, the fortitude to do something like what he did.”

• • •

As of 2018, Clarke’s novel 2001: A Space Odyssey has gone through well over fifty printings, selling in excess of four million copies. Before his association with Kubrick the author was considered one of science fiction’s “big three,” along with Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov. But 2001 vaulted Clarke into another category altogether. He was now truly world famous, and wealthy as well. While he may not have had a direct financial stake in the film, he had a significant indirect one, and his manifest loyalty to Kubrick, coupled by his patient tenacity in wrestling with 2001’s innumerable plot revisions, paid off hugely. His other work benefitted as well, with three new printings of Childhood’s End in 1969 alone. As Kubrick had predicted, everything came out all right in the end.

One of the deals that Clarke’s protégé Mike Wilson thought he’d made during an ill-fated attempt to take on the role of film producer during 2001’s final year of production concerned Childhood’s End. In 1967 he informed Clarke that he’d managed to sell the property to director John Frankenheimer, but like so much else with Wilson in the late 1960s, the deal soon fell through—and eventually, so did his relationship with an exasperated Clarke. The definitive break finally occurred in 1972, when Wilson filed a lawsuit trying to recover what he claimed as his property and cash from his erstwhile partner. The suit was settled out of court, and Hector Ekanayake took over as the primary beneficiary of Clarke’s extraordinary largesse. The James Bond parody that Clarke had been forced to finish was the last film Wilson ever made.

• • •

When the time came to finally vacate his studios and depart Borehamwood in February 1968, Doug Trumbull was told he couldn’t bring any of his working materials with him, and he flew back to Los Angeles with a bitter taste in his mouth. “I was to go back with my clothes,” he recalled incredulously. The following year, 2001 was largely shut out of the Oscars, having been nominated for four, including Best Picture. As previously mentioned, its sole award, for Best Visual Effects, went to Kubrick alone. It was the only Oscar the director ever received.

Trumbull has long maintained it was inappropriate for Kubrick to do what he did. “Those effects were not designed and directed by Stanley Kubrick,” he said categorically. Questioned further, he gave a little.

One directs the movie. You don’t direct the visual effects. You know, that’s a double-crediting thing that’s really not appropriate. Stanley was extraordinarily involved in directing the visual effects. There’s no question about it. He was on the set, telling the cameraman where to put the camera on a miniature shot. That’s directing special effects. Okay, so I don’t deny him that. But he didn’t design them, and he didn’t do them. There was a whole crew of people that did them. It’s like saying he did the costumes, or he did the whatever. So it was just really inappropriate, and I let it go by because I didn’t want to play out some contention in the press or the trades or anything like that.

There’s little doubt, however, that the first footage shot for 2001: A Space Odyssey—the Manhattan Project cosmological material filmed in noxious tanks of paint thinner, ink, and paint in early 1965—was designed by Kubrick, who also manned the camera. Produced before Trumbull’s direct involvement, it comprised about a third of the Star Gate sequence and was clearly a point of pride for the director.

In any case, throughout his post-2001 career, journalists and others would sometimes refer to Trumbull as having “done” 2001’s visual effects—a description that failed to mention the contributions of Wally Veevers, Con Pederson, Tom Howard, and Kubrick himself. This always irritated the director, who tended to blame Trumbull. At first, he sent warning notes, which his erstwhile protégé always responded to politely, stating that it was typical journalistic oversimplification, that he’d never be so crass as to try taking sole credit, and that Kubrick himself had been misquoted and mischaracterized often enough in the media that he should understand.

It all came to a head in 1984, when Hewlett-Packard published an ad featuring the lines “The year was 1968. But for the audience, the year was 2001. And they were not in a movie theater, they were in deep space—propelled by the stunning Visual Effects of Doug Trumbull.” At this, Kubrick and MGM threatened HP with legal action, and the company quickly withdrew its ad. This wasn’t enough for the director, however, who subsequently paid for a full-page message in the Hollywood Reporter. Quoting the offending copy in full, it said the ad had been withdrawn and that “Mr. Trumbull was not in charge of the Special Effects of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey.’ ” Published under the names Kubrick and MGM, the message proceeded to list 2001’s lead visual effects credits—with Kubrick first, Veevers second, Trumbull third, and Howard last—stating that the order reflected “the comparative contributions of the people principally responsible for the Special Effects work.”

This public slapdown, so similar to Kubrick’s disavowal of Terry Southern after Dr. Strangelove, was, of course, a humiliation for Trumbull, and led to a break between them that lasted for years. Finally, after about a decade, Trumbull—who considers the director “an absolute genius, and he was my friend, and he was my mentor and my teacher and my buddy, and I did a lot of really good stuff for him, and I was grateful to him”—decided to cold-call Childwickbury Manor. On reaching Kubrick, he said, “Stanley, I’m calling you because I wanted to tell you to your face that working with you was the most important thing that ever happened in my life. And I want to thank you.”

Kubrick responded with “Wow, thanks.”

Doug continued, “I just want you to know I’m here. I’m so grateful because everything I do every day harks back to that opportunity.”

It was the last time they spoke.

• • •

Kubrick never again attempted anything of the ambition, complexity, and scale of his eighth dramatic feature, 2001: A Space Odyssey. He did produce and direct five more manifestly innovative films, however: A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, and Eyes Wide Shut. All were exceptional, with Barry Lyndon in particular breaking new ground in its pioneering use of low-light cinematography. Deploying fast Zeiss lenses originally developed for the Apollo program, Kubrick and director of photography John Alcott, who’d graduated from the role of Geoffrey Unsworth’s camera assistant during 2001’s last year of production, took advantage of their extremely wide apertures to shoot interior scenes illuminated almost entirely by candlelight. The result was the first accurate representation of what eighteenth-century interiors looked like before the advent of electricity, giving the film the remarkable aspect of a period oil painting come to life. Alcott would win an Oscar for his work on the film.

Kubrick’s most controversial work by far was 1971’s dystopian, ultraviolent A Clockwork Orange, based on the Anthony Burgess novel— a film the director characterized as “a running lecture on free will.” Shot on a budget of only $2.2 million, it was a commercial success, but its graphic portrayals of murder and rape earned it an initial X rating in the United States. After episodes of supposed copycat violence and multiple threats to the Kubrick family, the director had the film withdrawn from distribution in the United Kingdom, where it remained effectively banned until 1999. It was another example of his unmatched clout with the studios.

The initial published responses to 2001: A Space Odyssey remain among the most widely cited examples of critical misfire, and the film is now regarded as among the most important motion pictures ever made. Yet its rise in critical estimation was surprisingly slow. Every decade Sight & Sound, the magazine of the British Film Institute, polls an international group of critics, programmers, academics, and cinephiles, asking them to rank the ten most important films of all time. Almost a quarter century passed before 2001 showed up in its widely respected decadal list, considered the best such survey in the world. In 1982 the film was a close runner-up but didn’t quite make the cut. 2001 finally entered the listing in 1992 at number ten. By 2002, it was ranked the sixth most important film in history, a position it retained in the last such survey, in 2012. (Hitchcock’s Vertigo is currently number one, and Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane second.)

That’s the contemporary critical establishment. At the same ten-year intervals, Sight & Sound also asks Kubrick’s peers—the world’s top directors—to render the same judgment. In this case, it took until 2012—a whopping forty-four years—for the film to make an appearance on their decadal Director’s Top Ten Poll. When it did, however, it landed with a bang, in second place. (Yasujirō Ozu’s Tokyo Story is the current number one, and Citizen Kane number three, after a long reign at the top.)

The American public seemingly arrived at a similar conclusion less than ten years after 2001’s release, however. In 1977 National Public Radio’s top news show, All Things Considered, conducted a poll among its 1.5 million listeners. Seeking to tabulate American cinematic tastes, the program asked which should be considered the ten greatest American films of all time. The results placed Citizen Kane first, 2001: A Space Odyssey, second, and Gone with the Wind, third.

Stanley Kubrick’s last public statement was in 1998. It came in the form of a video address transmitted to the Directors Guild of America on the occasion of his receiving its D. W. Griffith Lifetime Achievement Award. (Long considered among the most important figures in the history of feature filmmaking, Griffith, who lived from 1875 to 1948, was also highly controversial due to his use of racist caricatures in films such as The Birth of a Nation, which depicted the Ku Klux Klan in a heroic light.) Observing that Griffith’s career was “both an inspiration and cautionary tale,” Kubrick said the director “was always ready to take tremendous risks in his films and in his business affairs.” He meditated on how the man who’d transformed movies from a “nickelodeon novelty to an art form” had spent the last seventeen years of his life shunned by the very industry he’d helped create. For Griffith, Kubrick said, the wings of fortune “had proven to be made of nothing more substantial than wax and feathers.”

I’ve compared Griffith’s career to the Icarus myth, but at the same time, I’ve never been certain whether the moral of the Icarus story should only be, as is generally accepted, “Don’t try to fly too high,” or whether it might also be thought of as, “Forget the wax and feathers and do a better job on the wings.”

It was a statement he was uniquely qualified to make.

• • •

Stanley Kubrick died of a massive heart attack on March 7, 1999, less than a week after screening a fine cut of Eyes Wide Shut for his family and the film’s stars, Nicole Kidman and Tom Cruise. Close associates contend he undoubtedly would have made further edits after preview screenings, just as he’d done with 2001 and other pictures.

On hearing the news, Doug Trumbull—who, like many who’d worked with Kubrick, was profoundly shocked, and couldn’t easily conceive of the director as mortal—realized there would inevitably be a memorial service. He called Jan Harlan to see if he might be invited, and, on receiving the okay, packed his clothes, hopped a plane, and made it to Childwickbury Manor just in time. By all accounts, the service, which took place under a huge canopied tent on a cold and rainy afternoon, was beautiful and moving. It unfolded among an extraordinary display of flowers, most of them rooted in soil directly below a cover that had been stretched over the lawn. The family had received permission to bury him on the estate, and the service was conducted beside an open pit at the base of a large, symmetrical evergreen—Kubrick’s favorite tree. The coffin was carried in by a group of men that included Tom Cruise, after which several eulogies were delivered. These were punctuated by musical interludes performed in part by the Kubrick grandchildren.

Jan Harlan’s eulogy came first, and as film critic Alexander Walker recalled, it set the tone perfectly. Surveying the 150 or so people gathered, Harlan said, “I had no idea a week ago that I would be addressing the world’s greatest assembly of Stanley Kubrick experts.”

“So we all chuckled,” Walker said, “and we all relaxed.”

Other speakers included Cruise, Kidman, and Steven Spielberg. After almost two hours, the mourners were invited to take a rose from on top of the casket, drop it into the open grave, take a pinch of earth from one of the bowls arranged for that purpose and do the same, and say their goodbyes. Then the coffin was lowered into the grave.

Afterward, everyone was invited into the house for refreshments, and gathered around tables in the warmth of the Kubricks’ large kitchen. With night falling, at one point Spielberg leaned over to Walker and commented, “You know, this is extraordinary. In Beverly Hills, there would have been cops and bodyguards and velvet ropes and VIP enclosures. And here we are, eating supper in an English kitchen.” It was, Walker observed, “really one of the most intimate and affecting farewells to any friend that I could possibly hope for.”

Throughout the event, Doug Trumbull felt lucky to be there and found he was weeping openly at several points. Soon after retreating with everyone else to the kitchen and its “beautiful buffet, drinks, conversation,” he realized that Stanley was still outside. Slipping quietly back out the door, he took a chair, sat down by the open grave, and spoke to his old mentor. “Stanley, all this crap that happened was stupid, and that’s not what it’s about at all,” he said, tears in his eyes. “We’ve had our disagreements, and that’s been challenging, but I don’t care. I don’t care. None of that is important to me. I’m here because I love you, and I think that what you did was so important to cinema, and to my art form and to my life, and I’m honored to be here. Thank you for changing my life.”

After that, several workmen came and started filling in the hole with soil.

• • •

Arthur Clarke outlived Stanley Kubrick by almost a decade. Although he wrote nine novels following 2001—including three that took the Space Odyssey story forward, to mixed critical reception—he remained best known for the narrative they had produced together during their four intense years of collaboration between 1964 and 1968.

In 1984 a sequel to 2001 based on his novel 2010: Odyssey Two was released by MGM. Directed by Peter Hyams and titled 2010: The Year We Make Contact, it starred Roy Scheider and featured Keir Dullea and Douglas Rain reprising their roles as Dave Bowman and HAL. Passable as entertainment, it was ultimately forgettable.

In 1988 Clarke was diagnosed with the progressive neural disorder called post-polio syndrome, and he spent much of his last two decades in a wheelchair. It didn’t visibly affect the morale of a man whose curiosity and wonderment about the universe was matched only by his ability to convey it in clear, concise language. In 1994 Kubrick sent him a note apologizing for not being able to attend the taping of This Is Your Life, a BBC biographical program focusing on the author. “You are deservedly the best-known science fiction writer in the world,” he wrote. “You have done more than anyone to give us a vision of mankind reaching out from cradle earth to our future in the stars, where alien intelligences may treat us like a godlike father, or possibly like the ‘Godfather.’ ”

In 1998 Buckingham Palace announced Queen Elizabeth II’s intention to make Clarke a Knight Bachelor—the oldest such honor, dating back to King Henry III in the thirteenth century. The investiture was delayed, however, at Clarke’s request so he could clear his name after a British tabloid, the Sunday Mirror, took the opportunity to accuse him of pedophilia. The paper’s charge was backed by dubious quotes allegedly from Clarke himself, though he vehemently denied making them. When the Sri Lankan police requested tapes of the supposed interview, however, they weren’t forthcoming, and a subsequent police investigation found the accusation baseless. The Mirror subsequently published an apology, after which the author decided not to sue for defamation.

Arthur C. Clarke was duly knighted on May 26, 2000. As with his disability, the episode failed to quell his inherently hopeful, forward-looking character, nor did it interrupt his lifelong quest to understand and describe the human situation within a vast and cryptic cosmos—all of it in prose suffused by the specifically Clarkean optimism that was one reason for his worldwide fame.

A tendency toward self-aggrandizement wasn’t foreign to him—in fact, he mocked himself for it, sending out an email circular to his friends every winter that he called an “Egogram.” When considering his role in 2001: A Space Odyssey, however, he was curiously humble. “I would say 2001 reflects about ninety percent on the imagination of Kubrick, about five percent on the genius of the special effects people, and perhaps five percent on my contribution,” he had said in 1970. It was a remarkably self-deprecating comment, one unsupported by the evidence. He may have had Terry Southern in mind.

Asked in the year 2001 if he was disappointed that the grand vision of human expansion into the solar system that he and Stanley Kubrick had realized decades before hadn’t come true, Clarke mulled the question over for a minute, then replied that he really wasn’t, pointing to the robotic explorations that had opened the solar system to human eyes after millennia of speculation. Much more had been accomplished than he’d ever expected to see in his lifetime, he observed. A couple years later, he expanded on this, writing, “We are privileged to live in the greatest age of exploration the world has ever known.”

In his last “Egogram,” sent in January 2008, Clarke ruminated on the events of his ninetieth year. Although a typically cheery missive, he clearly sensed that something was coming. “I’ve had a diverse career as a writer, underwater explorer, space promoter, and science popularizer,” he wrote. “Of all these, I want to be remembered most as a writer—one who entertained readers, and, hopefully, stretched their imagination as well.

“I find that another English writer—who, coincidentally, also spent most of his life in the East—has expressed it very well. So let me end with these words of Rudyard Kipling:

If I have given you delight

by aught that I have done.—

Let me lie quiet in that night

which shall be yours anon;

And for the little, little span

the dead are borne in mind,

seek not to question other than,

the books I leave behind.”

Arthur C. Clarke died in Colombo on March 19, 2008, of respiratory complications leading to heart failure. He left explicit instructions that no religious rituals of any kind should be performed at his funeral, but a few hours after his death, a gamma ray burst of unprecedented scale reached Earth from a distant galaxy. More than two million times brighter than the most luminous supernova ever recorded, its energy had taken seven and a half billion years to arrive at the solar system—about half the age of the observable universe. Having traveled through space and time since long before our planet formed, for about thirty seconds this vast cosmic explosion became the most distant object ever seen from Earth with the naked eye.

It was the kind of salute even a lifelong atheist might have appreciated.