9

MARVEL COMICS MISCELLANEA

As alluded to a number of times earlier, Marvel was in a particularly precarious position at the end of the 1950s, when it came to the distribution of its comics. In fact, when the Marvel superhero boom of the 1960s hit, Marvel comics were actually being distributed by DC Comics. No, really!

During the early 1950s, when Timely changed its name to Atlas Comics, Martin Goodman distributed the comics through his own distribution company. However, toward the end of the decade he decided he wanted to expand the Atlas line of comics, so he signed a deal with American News Company, one of the largest distributors in the country, and a virtual monopoly. Actually, forget the “virtual” part, because in 1956 the U.S. government ruled that American News Company was a monopoly. Suddenly, Atlas was without a distributor, and since Goodman alienated all of his wholesalers when he made the move to American News, he could not go back to self-distribution. Therefore, his only recourse (besides shutting the company down entirely) was to go to Independent News, the distribution company owned by DC Comics!

Independent News agreed to the deal, under the condition that Atlas not publish more than eight books a month. Atlas went to a bimonthly schedule for all its books, which allowed it to put out sixteen titles, and with a bit of finagling it was sometimes able to put out ten books in one month if it put out six in the next.

This was particularly difficult during the early 1960s, when Marvel’s popularity was increasing and it had a number of characters who could carry their own title. Marvel’s only recourse was to split books between characters, which is why it had so many anthologies at that time, like Tales to Astonish and Tales of Suspense.

Eventually, in 1968, Marvel negotiated a slightly better deal from Independent News, which was when a number of its heroes received their own solo titles, including Captain America, The Incredible Hulk, and Iron Man. That same year, Marvel was sold to a company that eventually became known as Cadence Industries. In 1969, Cadence bought its own distributor, so Marvel was then free to put out as many comics as it wanted.

ARTISTS BREAK INTO working in comics in a variety of different manners, some stranger than others. But few have made as strange of an entry into the comic field as John Romita, the legendary comic book artist who, as noted earlier, was Steve Ditko’s replacement on Amazing Spider-Man and for many years Marvel’s art director. Romita received his big break by pretending to be someone else!

The story began in 1947, when Romita graduated from the School of Industrial Art, and after doing one story for Eastern Color Press’s Famous Funnies, found himself without any work in comics. In 1949 he was making thirty dollars a week working in New York City for Forbes Lithograph, when he ran into a friend from art school named Lester Zakarin, who offered him the break he needed. Zakarin would pay Romita twenty dollars a page (almost as much as Romita was making in a week!) if Romita was willing to pencil a comic story for him and allow Zakarin to claim that it was his own artwork. Zakarin was an inker but could not pencil very well. Zakarin would ink Romita’s pencils and submit the work as his own. The assignments were mostly for Stan Lee at Timely Comics.

One problem that arose was that Lee would often ask for corrections on the artwork from the penciller, and Zakarin could not make the corrections himself. The pair solved the problem by Romita going into the city with Zakarin and waiting at the New York Public Library, which was near Timely’s offices. Zakarin would tell Lee that he could not draw in front of people—he needed complete silence to work. He would then say he was going to the apartment of a friend and would bring back the corrections later, but he would really go to the library. Romita would do the corrections there, and Zakarin would bring them back to Lee.

Eventually, Romita went to visit Lee’s offices and told his secretary that while Lee did not know him, he had been working for him for over a year, and that he was the one actually drawing Zakarin’s artwork. The secretary went to see Lee and returned with Romita’s first assignment as John Romita. Of course, the kicker is that they assumed Romita was penciling and inking the comic, and Romita had never inked a comic before, but he was not about to risk losing the job, so he inked himself, for the first time ever. And he has never stopped working in comics for the past fifty years. Romita’s son, also John, even became a Marvel artist and just recently celebrated thirty years of working at Marvel.

STEVE DITKO’S DISTASTE for Marvel (elaborated on pages 108-9) is well known. Even though he eventually did go back to working for Marvel in the late 1970s after Charlton, his preferred comic book employer, ceased to be a viable working choice, for a man who worked for Marvel well into the 1990s (when he more or less retired from regular comic book work), his displeasure with his past works for Marvel is so dramatic that he apparently even takes it out on his old work itself!

Up until the 1980s, original comic art was not returned to the artists. It was considered property of the comic companies, and, at DC at least, old original artwork was eventually shredded (although certainly a number of pages “found” their way into the personal collections of DC staffers). During the 1980s, Marvel was in a dispute with artists over whether it owned the original work or was just paying for the production of the art, with the final ownership of the artwork belonging to the artists. Marvel eventually relented, under the following condition: it would give the artists back the art, but it would be as a gift out of Marvel’s generosity. Marvel still believes that it owns the work fair and square but magnanimously allows the artists to have it. Ditko disagreed with this position vehemently and would not acknowledge the returned art.

This artwork, particularly when it features famous Marvel super-hero characters, can easily sell for hundreds of dollars (and the really popular stuff for thousands) if the artist is famous like Ditko or Jack Kirby. However, when comic historian Greg Theakston visited Ditko a number of years ago, he noticed that the cutting board (which is exactly what it sounds like—a board on which you cut things) Ditko was using was an original cover from the 1950s! When Theakston expressed shock, Ditko told him to move a nearby curtain—behind it was a stack of original art almost two feet tall. Ditko wanted nothing to do with this old work and was in fact using it for cutting boards! When Steve Ditko takes a position, he takes it seriously.

IN THE EARLY 1970s, the toy company Mego began to produce a line of action figures, licensing superheroes from both Marvel and DC, including Spider-Man, Superman, Batman, and Captain America. The title of the line was World’s Greatest Super-Heroes. Mego decided to apply for a trademark (and was granted one) for the term super-hero. DC and Marvel took issue with this and threatened legal action, which Mego avoided by giving up its rights to the term (some stories say it sold any rights it had for the nominal fee of one dollar).

DC and Marvel then decided to register the trademark themselves. It was granted in 1981, and just recently DC and Marvel filed renewal papers for the trademark. The idea of two companies sharing a trademark is uncommon but not that out of the ordinary. The theory behind the trademark is that when someone thinks of the word super-hero, they will almost certainly think of either a DC or a Marvel property, and if a comic book or a toy product comes out with the term super-hero on it, consumers will presume it is a DC or a Marvel product.

Marvel and DC have already kept one comic book creator from using the term super-hero in the title of his comic book (even though it was spelled differently). They sent Dan Taylor, creator of the comic book Super Hero Happy Hour for the comic company Geek-Punk, a cease and desist letter.

While Taylor retitled the book Hero Happy Hour to avoid litigation, it would be interesting to see whether the trademark would hold up if anyone were to actually litigate the matter with Marvel and DC.

IN FANTASTIC FOUR #52, published in 1966, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby introduced the Black Panther, the first black superhero. T’Challa is the chief of the Panther tribe and also the ruler of the fictional African country Wakanda. His ceremonial title is the Black Panther. He wears an all-black costume with a panther mask and is a skilled fighter and one of the smartest men on planet Earth.

In 1968 T’Challa left Wakanda for a time to become a member of the superhero team the Avengers and to live in the United States under an assumed name to see what living as a typical American would be like. Eventually, he left the Avengers to return to rule his kingdom.

The Black Panther debuted in early 1966. In October of the same year, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California. The group, which was initially designed to protect African American neighborhoods from police brutality, radicalized as time went on, as Newton and Seale’s vision of “Power to the People!” split with other party members’ view that the group should be about “Black Power!”

While this was going on, the Marvel comic book character continued to appear in the pages of The Avengers, but when he left the book in the early 1970s, Roy Thomas felt it would be prudent for Marvel to change T’Challa’s name to something other than Black Panther. In Fantastic Four #119, the Thing and the Human Torch get caught up in an international problem when T’Challa, who is in pursuit of some bad guys, gets arrested in Rudyarda, a stand-in for South Africa. When Ben and Johnny free T’Challa, they are unprepared to hear him exclaim, as he knocks out a pair of guards, “You have done enough, Torch. Do not seek to do all of my fighting for me. Some things, after all, are best left to—the Black Leopard!”

When the Thing questions the name change, T’Challa explains that he plans on someday returning to the United States, and when he does, he knows that Black Panther has political connotations, and while “I neither condemn nor condone those who have taken up the name—but T’Challa is a law to himself. Hence, the new name—a minor point, at best, since the panther is a leopard.”

The name change did not last that long, and by the next time T’Challa showed up in a comic he was being called the Black Panther again. It probably had something to do with the Black Panther Party really coming apart a bit during the early 1970s. If it had remained more of a cohesive, active unit, it is likely that Marvel would have continued to distance itself from it, but by the early 1970s it was more or less nonexistent, as far as a serious radical party goes. The Black Panther, meanwhile, has had a few series since then, including a current ongoing title, in which he has taken the X-Man Storm as his wife and the new queen of Wakanda.

LUKE CAGE, HERO for Hire was a Marvel comic that was one of the first books to star an African American superhero. Carl Lucas was thrown into prison as a young man for a crime he did not commit.

He agreed to participate in some experiments in exchange for his parole. The experiments were nominally designed to help cure illnesses but instead resulted in Lucas gaining skin that was bulletproof and becoming a great deal stronger. After being cheated out of his parole, Lucas decided to escape from prison, and once on the outside, he took the name Luke Cage and made himself available as a superhero for hire (although he usually turned down payment when it came to that point).

After a while Marvel decided to help the book’s sales by giving Lucas an official superhero name, Power Man. This still did not help sales that much, so Marvel decided to team him up with a similarly low-selling title, the kung fu comic Iron Fist. Power Man and Iron Fist was a success, lasting six years.

Luke Cage made an impact at Marvel, being its first comic starring an African American hero, but it also had an impact in an area outside of comics, namely in the world of acting.

Aspiring actor Nicolas Coppola was concerned that wherever he went there were sneers and cries of nepotism because of his famous last name, courtesy of his uncle, the legendary film director Francis Ford Coppola. So the young Coppola decided to pick a stage name. He had always been a big fan of superheroes, ever since he learned how to read by reading comics, so he ended up taking the last name Cage, perhaps seeing something of himself in the streetwise hero. In later years, Cage would note that he also enjoyed the work of the avant-garde composer John Cage, and some people presume it was he whom Cage took his name from. But in recent years, Cage has made it clear that, while he enjoys the work of John Cage, it was Luke Cage that inspired his name.

From the Marvel Comic adapted film Ghost Rider.

Cage’s interest in comics did not end there. He put together an extensive comic collection, which he sold (after he married Lisa Marie Presley) for 1.6 million dollars. In addition, his son with his current wife, Alice Kim, is named Kal-El, after Superman’s Kryptonian name. Cage even played a superhero recently in the film version of Ghost Rider.

AS NOTED EARLIER (on pages 140-41), Steve Englehart was a popular writer for Marvel who was not one to shy from controversial topics, including the story line he did for Doctor Strange during the early 1970s, which got so touchy that he felt it necessary to fake a letter from a minister to support himself!

Doctor Strange was created by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, and it tells the story of a rich and powerful surgeon named Stephen Strange who has a callous disregard for humanity. When a car accident causes his hands to shake too much to do surgery anymore, Strange searches for a hermit known as the Ancient One who could cure him. When he finds him, the Ancient One refuses to cure him but offers him an apprenticeship in the mystic arts. Strange refuses, but after discovering that the Ancient One’s current apprentice, Baron Mordo, is trying to kill the Ancient One, Strange’s humanity finally returns. He takes the apprenticeship so that he can learn enough magic to stop Mordo. A new man, Strange becomes the most powerful magician in the world, the Sorcerer Supreme, as it were, and dedicates his life to helping humanity.

Englehart began work on the character in 1973, with artist Frank Brunner, in an epic story in which Doctor Strange follows around a being called Sise-Neg (genesis backward) who turns out to be God, and Strange is there when God creates the universe. When the issue was released, Stan Lee was frantic. Marvel needed to print a retraction to say the character was not God, just a god. Englehart and Brunner felt this would ruin the story, so they came up with a plan. Englehart happened to be traveling through Texas for one reason or another (a comic convention perhaps), so they created a fictional person, a Rev. Billingsley in Texas, who wrote a letter saying that a young boy in his parish had given him the comic and the reverend felt it was the best comic he ever read!

Marvel then told Englehart that he did not have to print the retraction. Instead, it was going to print the letter in the letters column as proof that the story was not offensive!

NOT ONLY DID Luke Cage’s name have an effect on Nicolas Cage, but his superhero name, Power Man, led to a bit of an amusing spat between Marvel and DC over the word power.

In 1964 Marvel introduced a new member of the Avengers, Wonder Man. He turned out to be a bad guy in disguise, but in the end he became a good guy, sacrificing his life to save the Avengers. Apparently, though, DC was miffed that Marvel was using the word wonder, because it felt that it took away from its character Wonder Woman. Wonder Man dies in the issue in question, so it was not a pressing matter, but Marvel agreed anyway not to have a character named Wonder Man.

A decade later, Marvel gave Luke Cage his new superhero name, Power Man. A year later, though, former Marvel employee Gerry Conway introduced a new member of the DC’s All Star Super Squad—Power Girl, Superman’s cousin.

Whether DC actually gave Marvel problems or not, the key was that Jim Shooter believed that DC had given Marvel a problem over the use of the word wonder, and then a year after Marvel introduced Power Man, DC introduces Power Girl? That was certainly cause for irritation.

So Shooter quickly moved for Wonder Man to come back from the dead. He did so in The Avengers #151 and #152, which came out later in the same year as Power Girl’s debut. An interesting situation happened in The Avengers #151. Because of delays over the script (Steve Englehart had left the title but still owed a script for his last issue), Gerry Conway (who had come back to Marvel) ended up scripting part of The Avengers #151 for Shooter, so Conway ended up both introducing Power Girl, which caused the problem, and writing Marvel’s retort to Power Girl’s introduction—so he was essentially responding to himself!

Wonder Man ended up becoming a popular Marvel character and even had his own title for a few years in the 1990s. Power Girl, though, has also been a popular DC character, and it was recently announced that she too would be getting her own ongoing title.

AS MENTIONED (on pages 127-28), Marvel has been very protective of its trademarks over the years, and that includes being on constant lookout for names that might be used that are similar to notable Marvel characters. This was the case when Marvel raced to come up with a Spider-Woman character so as to register a trademark of the name before another company used it.

The cartoon studio Filmation Associates had a cartoon show starring Tarzan in the mid-1970s. It found that the show was even more popular when it was combined with Batman the next season to form The Batman / Tarzan Adventure Hour. Seeing that this arrangement was working, Filmation’s next move was to expand the show to include five other superhero characters, this time all-new characters (so Filmation would not have to pay licensing fees, like they had to for Batman). Well, one of those new characters was to be called Spider-Woman.

When news of this came down the grapevine, Marvel knew it had to respond quickly, for fear that Filmation would have something published first. So writer Archie Goodwin had to come up with a Spider-Woman character and concept for Marvel in a very short period of time. With the help of artists Sal Buscema and Jim Mooney, Marvel rushed production of Marvel Spotlight #32, starring Spider-Woman.

The filing for trademark protection was almost instantaneous. The comic was released in very late 1976, and Marvel was awarded trademark protection in early 1977. Hanna-Barbera Filmation ended up changing its character’s name to Webwoman.

In his rush to get a product out there, Archie Goodwin actually ended up using Len Wein’s initial origin story for Wolverine (as noted on pages 151-52). In her first appearance, Spider-Woman is an actual spider evolved by the High Evolutionary into a Spider-Woman, just like Len Wein had planned for Wolverine. In fact, note that the last time the X-Men comics mentions the origin is in 1976, right before the creation of Spider-Woman! It is more likely that Chris Claremont just chose to use a different origin of his own volition, but it is not outside the realm of possibility that he was told that the mutated-wolverine origin was off-limits after it was used for Spider-Woman.

Afterward, when Marvel had time to think the character out, Marv Wolfman was assigned to write Spider-Woman’s ongoing series, and the first thing he did? Get rid of the mutated-spider origin.

SPEAKING OF PICKING up good names, in 1964 Stan Lee grabbed a great name that had gone unprotected while a rival company was out of business, when he launched Daredevil #1, using the same name of the popular Lev Gleason Publishing hero of the 1940s. Daredevil was an interesting character for Marvel, and his origins had an even more interesting source.

Daredevil followed in Stan Lee’s formula of heroes with problems. The titular hero was Matt Murdock, a successful lawyer who was blinded as a child when he pushed an old man out of the way of a truck carrying radioactive waste. The waste hit Matt in the face, blinding him but also secretly giving him a sort of radar sense that allows him to “see” people, in some way, better than other people can because all of his other senses were enhanced.

Stan Lee has spoken on the topic of the origin of Daredevil, and he claims that the idea was his. Still, there are situations in the life of artist and cocreator Bill Everett that seem to suggest that Lee may be mistaken. Bill Everett’s daughter, Wendy, is legally blind, and she recalls that she and her father discussed the idea of a blind super-hero, partially based on the fact that her other senses were more highly attuned due to the loss of her sight, which would seem to translate well to a superpower.

So while Lee feels that he came up with the idea on his own, when the other cocreator of a blind superhero has a blind daughter, whether she remembers her father creating the character or not (which, in this instance, she does), it seems to suggest that the odds are that Everett had more to do with the blind part of Daredevil than Lee believes.

STAN LEE OCCASIONALLY finds himself in a position where his often unreliable memory gets him into a bit of trouble, which was the case when he tried to out a comic character from the 1960s.

Lee was being interviewed in 2002 by a conservative group, the Traditional Values Coalition, discussing a recent Marvel comic miniseries that starred a Marvel Western character from the 1950s and ’60s, Rawhide Kid, in which it was revealed that said character was gay. The issue caused a bit of an uproar, and while being interviewed, Lee attempted to downplay the significance of the character being gay. In fact, said Lee, it is not even that surprising, as Lee had written gay characters into some of his comics in the past. The claim seemed a bit dubious, so the interviewer asked him to name one, and Lee decided to name Percival “Percy” Pinkerton, a member of Sgt. Fury’s Howling Commandos.

Pinkerton’s first appearance from Sgt. Fury #8, with art by Dick Ayers.

This decision came as a surprise to readers of that series, as Lee had always written the character, who was based on the British actor David Niven, as a bit of a playboy—very much interested in women. Another voice of dissent was artist Dick Ayers, who worked on the series with Lee after Jack Kirby left. He said that this current view of Percy Pinkerton bore no resemblance to how Lee wrote the character at the time—and Ayers should know, since he worked with Lee on the character.

It appears that Lee was basing his sudden choice on the facts that he had written the British character to be a bit of a fop and that his name has the word pink in it. Not much to go on, but it had been forty years since Lee had written for the character. Ultimately, Lee admitted that, yes, he was just confused and had misremembered the character.

WHILE BOTH DC and Marvel had their share of popular successes with licensed comics, when Marvel first began considering them in 1970, it was extremely wary. In fact, Stan Lee originally turned down the chance to produce Conan the Barbarian comic books!

Roy Thomas was a huge fan of the classic Robert E. Howard pulp series about the mighty barbarian, Conan, who is a Cimmerian warrior who slowly worked his way up from his life as a thief until he was eventually king. Howard’s stories were widely influential in the world of fantasy, and Thomas was not the only one at Marvel who was pushing for a Conan series—artist Gil Kane had wanted to do one for years.

However, Stan Lee did not think that publisher Martin Goodman would go for paying the licensing fee. Thomas wrote a detailed memo explaining to Goodman why it made sense to not just do a sword-and-sorcery book but to specifically license one of the famous sword-and-sorcery characters, because that was what the fans were writing in for and specifically asking about. They weren’t saying, “Give us fantasy comics,” but “Give us Conan comics!”

Ultimately, Thomas’s memo was so persuasive that Goodman opened up a small licensing budget and left it to Lee to determine which book they would go after licensing. Lee decided not to pursue Conan; instead he authorized Thomas to try to license author Lin Carter’s barbarian hero Thongor, only because Lee thought Thongor sounded like a more interesting name than Conan. Thomas contacted Carter, but there was an impasse: Carter was looking for more than the $150 licensing fee Thomas was authorized to spend. When Carter stalled, Thomas made an executive decision and decided to contact the representatives for Conan.

When Thomas sealed the deal, he had a problem getting an artist, because the two artists who would most love doing a Conan comic, Gil Kane and John Buscema, were too expensive for the extremely small budget Goodman gave the new title. Since he was on a budget, Thomas had to use a cheap artist, but lucky for him that cheap artist was Barry Windsor-Smith, a young penciller who would soon become a major comic book star due to his detailed and striking action work on Conan the Barbarian.

The book started slow, saleswise, but sales soon kicked in, and before too long, Marvel was publishing multiple Conan comic books, as well as a black-and-white magazine starring Conan. Suddenly, John Buscema and Gil Kane were affordable for the comic.

YOU WOULD NOT think that lightning would strike twice, but in a way that is what happened later in the decade when Stan Lee turned down the opportunity to do a Star Wars comic book!

In 1976 Roy Thomas received a visit at his apartment from Charley Lippincott, who was in charge of merchandising and publicity for Star Wars, and he told Thomas that George Lucas wanted Marvel to adapt Star Wars into a comic book form to be released before the movie to drum up interest in the film. He admired Thomas’s work as an adapter for the Howard comic titles (which, by this time, numbered quite a few comics), and specifically asked for him to do the adaptation.

Thomas, of course, appreciated the flattery, but told him that he had not been editor in chief of Marvel in a few years, so he had better talk to Stan Lee. Lippincott then told him that he had, that and Lee had turned him down flat. Now, Thomas was wondering what they expected from him—and they had their answer. They asked to show him a series of paintings detailing the story of Star Wars, and he acquiesced. By the middle of the presentation, Thomas was hooked. He was willing to talk Lee into doing the adaptation, which was simpler than Thomas thought, perhaps mostly because adapting a film before it is released is basically doing advertisement for the film—so it does not cost much in terms of licensing fees.

The adaptation turned out to be helpful for the film but hugely beneficial for Marvel (although Thomas left fairly early on, because the Star Wars people were a bit too hands-on with their comments).

In the years since, Jim Shooter, Marvel editor in chief at the time, has said that Marvel was in rough shape in the late 1970s, and the massive sales success of Star Wars helped save the company. So it seems that all’s well that ends well—just so long as you don’t take your first no from Stan Lee as the final answer.

SINCE HE STARTED inking Conan with issue #26 in 1973, artist Ernesto “Ernie” Chan has inked more pages of Conan artwork than any other artist in comic book history. However, shockingly, for years the popular artist had to go under a different name—all because of a typographical error!

Born in the Philippines in 1940, Chan worked in the Philippines comic industry, along such great Filipino artists as Alfredo Alcala, Tony DeZuniga, Nestor Redondo, Danny Bulandi, and Romeo Tanghal. DeZuniga was one of the first Filipino artists to hit it big in America, so Chan came to the United States to apprentice with him in the very early 1970s. Eventually Chan got work at DC Comics and then at Marvel, where he began his long tenure as inker for Conan.

While working on covers at DC, though, Chan had an interesting credit—his work was signed Ernie Chua. The problem was that there was a typographical error on Chan’s birth certificate, so when he immigrated to the United States, that is the name that was on his immigration papers, and therefore on his other legal documents, including all his tax papers. When he became a U.S. citizen, he was able to go back to his actual name and began being credited correctly.

Years later, Chan was asked why the immigration officials weren’t willing to fix the simple error, and he gave a rather scary answer. The official told him the erroneous name would be better for him, because “there are too many Chans in the United States.”

ANOTHER INTERESTING TIE-IN with another medium took place in the late 1970s, when Casablanca Records contacted Marvel about a new comic book idea. Casablanca Records was founded by Neil Bogart, and it was at the forefront of the disco revolution, with, among others, its biggest star, Donna Summer. While Casablanca was mostly known for its disco records, it was also the record company of the rock band Kiss.

In any event, in the late 1970s, Casablanca approached Marvel about doing a comic book series about a singer. Marvel would create the series about the singer, and then Casablanca would provide a singer who matched that description, and it would be a back-and-forth joint publicity effort. The comics would promote her records, and the records would promote the comic book, and there was also going to be a film tie-in. It was a fine idea, but it all fell apart after the initial development because Casablanca just couldn’t determine what it wanted exactly from writer Tom DeFalco, besides something along the lines of a character named the Disco Queen. The project ultimately ended up in developmental limbo.

It stayed in limbo until almost two years later, when the project resurfaced, this time as a film starring Bo Derek (the record tie-in might have still been in play, but I do not believe so), which would be called Dazzler. So the features of the character (which were originally those of an African American woman) were changed to be like Bo Derek, and the character made her debut in an issue of Uncanny X-Men.

The film never came to be, but Dazzler has been a mainstay in the Marvel Universe ever since.

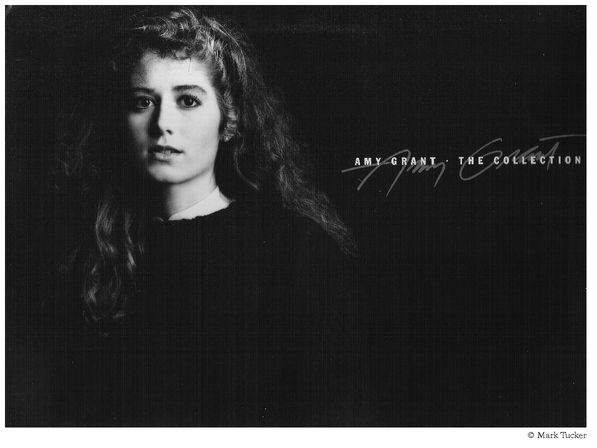

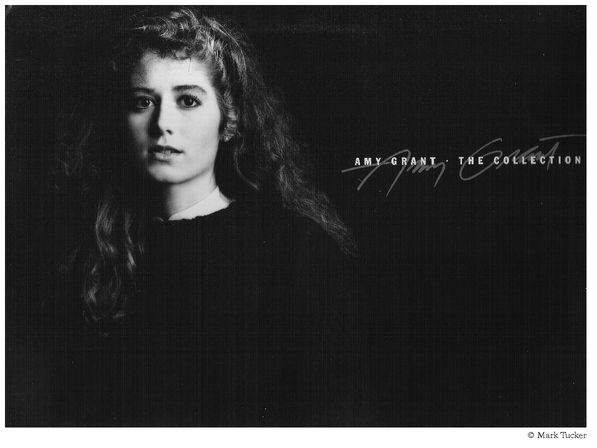

WHILE BO DEREK might have enjoyed seeing being immortalized in a comic book, one performer who had a major problem with it was singer Amy Grant.

In 1986 Amy Grant released The Collection, a greatest-hits package of her work to that point, which became an extremely popular album (going platinum at least once).

In early 1990, Doctor Strange: Sorcerer Supreme #15 came out. It was the second part of a five-part story that involved Marie Laveau, based on a real-life American woman who practiced voodoo in New Orleans in the nineteenth century. On the cover, artist Jackson Guice depicted the character named Morgana Blessing with a look familiar to Amy Grant fans—the image of Grant as it appeared on the cover of The Collection.

Soon after the issue came to their attention, Amy Grant’s management team, Mike Blanton and Dan Harrell, quickly filed a complaint against Marvel Comics. Here is where it gets tricky. They were not, as many folks think, suing over copyright infringement. First off, the copyright for the photo belonged to photographer Mark Tucker (an accomplished Nashville commercial photographer, whose work has graced a number of records), so that wouldn’t work.

No, the complaint, filed by Blanton and Harrell in federal court in Tennessee, was related more to the fear that it would appear that Grant was authorizing the use of her likeness and was therefore condoning the comic book, which would affect her standing in the Christian music community. Reading from the complaint: “Many fans of Christian music consider interest in witchcraft and the occult to be antithetical to their Christian beliefs and to the message of Christian music in general. Therefore, an association of Amy Grant or her likeness [with Doctor Strange] . . . is likely to cause irreparable injury to Grant’s reputation and good will.”

A U.S. district court sealed an out-of-court settlement between Grant and Marvel in early 1991, with a consent decree that Marvel did not admit to any liability or wrongdoing.

The issue may or may not have been asked to be pulled from stores, but since it was a monthly book, such an order really doesn’t have much of an effect. An order to remove is not that effective when the item is a periodical, since the issue is usually sold out by the time it is ordered to be removed, and in fact sometimes the next issue has already come out!

GHOST RIDER, WHICH was made into a film recently starring Nicolas Cage, is the tale of a motorcycle stunt rider named Johnny Blaze who sold his soul to Satan to save someone he loves, which resulted in Blaze becoming bonded to a demon named Zarathos. When using his powers, Blaze’s flesh is consumed by hellfire, causing him to have a flaming skull. He also rides a motorcycle made out of flames. With all this talk of demons, you might think that there might be some religious controversy surrounding Ghost Rider, and if so, you would be correct.

When the creator of Ghost Rider, Gary Friedrich, left the book, writer Tony Isabella took over the title.

Soon into his run, Isabella decided to have the book break away from Friedrich’s style (presumably thinking, “He did it so well, let’s try something different”), and Isabella made Ghost Rider into a bit more of a superhero. At the same time, he also attempted to examine some themes of redemption with the character.

One of the first things Isabella did (using a suggestion by writer Steve Gerber, to whom Isabella had told his plans for the book) was to introduce, as a supporting character, none other than Jesus Christ. The idea being that since Ghost Rider had a deal with Satan, wouldn’t God want to get involved? Thus we saw the introduction of the Friend, a sage traveler with long hair and a beard who would assist Ghost Rider in redeeming himself.

The story line continued for two years. However, when it came down to the conclusion, the book’s editor, Jim Shooter, took issue with the story line, as he disagreed with the idea of having Jesus in the book.

Therefore, for Ghost Rider #19, Shooter rewrote the issue and had some of the art partially redrawn. The new story revealed that the Friend was actually a demonic illusion meant to trick Ghost Rider. Shooter felt this was less offensive than Jesus Christ actually appearing in a comic book. Isabella, expectedly, disagreed and quit the book.

A little while later, writer Roger Stern took over the book and made another change to the story of Ghost Rider in the name of being inoffensive to the religious. Now, rather than it being Satan who Johnny Blaze was involved with, it was the fictional Marvel demon Mephisto (who first appeared as a nemesis of the Silver Surfer). Stern thought it made more sense for it to be an established Marvel character behind Ghost Rider’s origin and, at the same time, that it would be less offensive to religious readers who believe in Satan.

It’s interesting to see how religiously sensitive Marvel is over what is essentially a demon riding a motorcycle! I doubt the extremely religious would be pleased with the concept no matter what.

JIM STARLIN’S RUN as writer-artist of Warlock was one of the most acclaimed comic book runs of the 1970s. Starlin masterfully worked into the story line a gigantic space opera involving a genetically engineered human named Adam Warlock, a green female assassin named Gamora, and a foul-mouthed troll named Pip, issues with organized religion and the difficulties that arise in personal-identity conflicts (personified in a hero fighting against his evil self from the future).

While the series was critically acclaimed, it did not sell that well, and Starlin ultimately had to resolve all of his story lines in the pages of other comic book titles. He did write one last issue of Warlock in the late 1970s, which was drawn by artist Alan Weiss and designed as an inventory story in case Marvel ever had use for it (during the 1980s Marvel actually started a series that published the best of these inventory stories, called Marvel Fanfare). A strange problem quickly arose, though, when the artwork for the issue disappeared. The reason for the disappearance was even stranger. It had been left in the backseat of a cab!

Weiss had just flown into New York, and some folks from Marvel met him at the airport to help him carry his belongings, as he was going to move in with another Marvel artist, Al Milgrom. When he arrived, one of the people there (Weiss specifically refuses to say who, but it is worth noting that when he tells the story he names everyone who was there except the fellow whose apartment he was going to share) helped him carry his bags, and this person picked up a box containing the pencils for Warlock #16. When they arrived at the apartment, the box was missing—presumably circulating in a cab somewhere in the New York metropolitan area!

Interestingly enough, copies were apparently made of the issue, so during the early 1990s there were plans to redo the issue for Marvel Fanfare, but then Marvel Fanfare was canceled. Then later on in the 1990s, Marvel planned to feature the story as a special issue of Warlock’s current book (Starlin had relaunched the character’s title in 1992), but then that book was canceled before they had a chance.

The fates, it seems, do not want Warlock #16 to ever see print.

IF IT WAS Milgrom who lost the art, he made an even bigger mistake some years later—a mistake so big that he lost his job over it!

At the turn of the twenty-first century, Milgrom was working on the Marvel staff as an inker. He would ink some books and troubleshoot for other books that needed help with deadlines. At the time, the editor in chief at Marvel was Bob Harras. Harras was fired in August 2000 and replaced with Marvel’s current editor in chief, Joe Quesada.

Milgrom was one of three inkers on a one-shot comic called Universe X: Spidey (Universe X was part of a trilogy of alternate-future comics, after the success of a similar concept called Kingdom Come that Alex Ross had cocreated for DC Comics with Mark Waid), inking the pencils of Jackson Guice (the artist from the Amy Grant incident on pages 181-82). At one point in the story, Al Milgrom snuck into the background of a panel, along the spines of books on a bookshelf: “Harras, ha ha, he’s gone! Good riddance to bad rubbish. He was a nasty SOB.”

The panel was caught before the book went to print, but, apparently due a communication error in the production department, the book was printed with the panel intact. Marvel then pulped the entire print run and reprinted the book with the panel edited. At the time, the higher-ups at Marvel wanted to terminate Milgrom and never have him work for Marvel again.

Ultimately, Quesada managed to get them to allow Milgrom to continue to work at Marvel on a freelance basis, although his staff position was taken away. Also, part of his payments would be deducted to pay for the cost of pulping and reprinting the comic (a sizable amount of money, well over twenty thousand dollars). Jim Starlin quickly arranged for Milgrom to work on a number of projects with him. Nowadays, though, Milgrom is working as an inker mostly for Archie Comics.

An interesting (and relatively believable) conspiracy theory that the issue was printed even after the mistake was caught because the pulping of the book would be “just cause” to terminate Milgrom without having to pay him severance. This seems unlikely, as it is doubtful that the severance would be any cheaper than the cost of pulping the book, not to mention the time and effort to do the pulping and to supervise the new printing.

Amusingly enough, when the issue was reprinted as part of the Universe X collection a year or so later, the same mistake was repeated—so the trade paperback was printed with the insult still there!

MARK GRUENWALD WAS a beloved editor and writer at Marvel Comics for many years. Gruenwald was heavily involved in comic book fandom prior to being hired at Marvel in 1978, where he quickly rose in the ranks to becoming a full editor. He was a fixture of Marvel until his death in 1996, and it is only fitting that a piece of him lived on at the company after his death.

Despite a remarkable eight-year run as the writer of Captain America, the work that Gruenwald was most proud of at Marvel was Squadron Supreme. Created by Roy Thomas as a joke between Thomas, then writer of The Avengers, and Denny O’Neil, then writer of DC’s Justice League, the Squadron was made up of analogues to DC’s Justice League. Hyperion was Superman, Nighthawk was Batman, Power Princess was Wonder Woman, etc. The Squadron Supreme lived on an alternate Earth. In 1985 Gruenwald did a twelve-issue series detailing what happened when the Squadron Supreme decided to use their powers to fix our Earth, by taking it over themselves. It was a brilliant look at a realistic demonstration of what superheroes could do in the “real” world and whether it was something that would be at all beneficial for society. A benevolent tyranny is still tyranny. The series is well remembered as one of the first “serious” comics, and Alan Moore’s classic series Watchmen, which began the next year, is similar in scope.

When Gruenwald died of a heart attack in 1996, his will asked that he be cremated and that his ashes be mixed with the ink used to print a comic book by Marvel. The Marvel editor in chief at the time, Bob Harras, along with Mark’s widow, Catherine, decided to choose the first printing of the first trade paperback compilation of Squadron Supreme.

Mark Gruenwald was part of Marvel for almost two decades—now he will be part of Marvel Comics forever.