Chapter Six

EVACUATION

Savenay was a rest camp between Nantes and St Nazaire, situated just above the small Breton town in pleasant open country. The huts were built near what appeared to have been the local racecourse and very few troops were in occupation. It was presided over by an elderly gunner subaltern who had been a ranker in the First World War and knew what the men wanted so he applied himself with some diligence to making the place comfortable. When our sections arrived, after their withdrawal from the Seine and the long trek westwards across France, Savenay seemed like a benediction on the weary travellers. Here they could eat, bathe and sleep without even an air raid. This lasted for several days. An occasional visit to the local estaminet enabled them to listen to wireless reports from the BBC and Radio Paris, at the same time as sampling the excellent meals and marvellous cellar. Life would have been fairly kind but for the ominous news reports.

When all the sections had got back to Savenay, apart from Don Terry’s party, it transpired that the oil tanks at Honfleur across the Seine estuary from Le Havre had not been destroyed. The omission had come about because the officer in charge of the most westerly of the oil installations at Le Havre, Don Terry, had been under naval command at the port and had not appreciated that the Honfleur tank farm was part of his ‘show’. Don Terry and his section, after helping to destroy the port installations had, as you will remember, already left for England on a destroyer.

Tommy Goodwin with Second Lieutenant Whitehead, Lance Sergeant Ward and about eight sappers very courageously volunteered to go back the whole way to Honfleur despite the very fluid situation as regards mechanized German patrols.

When I arrived at Savenay I found that Peter Keeble, who had done the original reconnaissance, had arrived before us and had moved out with his party on his own initiative to tackle another dump. He had been advised when he initially came over to France, not only of the details of the Seine installations but, in passing, he was told that there was an enormous BEF fuel dump in the forest of Blain down near St Nazaire. Although it had nothing to do with our tasks on the Seine, he had remembered this information.

The dump turned out to be of considerable size and area. Here at Blain was a prize indeed for the Germans. The huge dump of petrol in forty gallon drums and four gallon tins were in well separated piles as a precaution against fire accidentally spreading. These were piled up in square stacks leading far into the forest with a complete network of roadways and paths. It stored the main BEF stocks of petrol and aviation spirits for the RAF. Despite the obvious hazards in tackling this dump Keeble made the very courageous decision to carry on although he was doing it on his own initiative. This task was quite different from any of the previous ones and in any case by now they had expended all their explosives. They had no alternative but to resort to the highly dangerous practice of breaking open the drums of volatile liquid with pickaxes and bayonets; sparks were inevitable. The weather was hot and it had not rained for some days so everything was tinder dry. When they had finished holing a few of the drums in every pile, the smell of petrol vapour inside the forest was almost overpowering. In these circumstances Keeble decided to light the dump at the upwind end and allow the wind and burning tinder to do the rest of the job. The party withdrew to the upwind side of the wood and Keeble ignited the nearest drums by firing a Very Light cartridge into the petrol on the ground; the fire spread at a frightening pace down the length of the whole wood. One pile of drums had accidentally caught fire prematurely, nobody was quite sure how, and two men came out very badly burned. And at the end of the task when Keeble checked the numbers there was one man missing. Though they searched for him as best they could it was impossible to get inside the forest which was now engulfed in flames and sadly what happened to him will never be known. The two men with burns survived and happily made it back to England.

Through the last peaceful day or two that ensued we had little accurate knowledge of what was happening. Daily intelligence reports collected from British HQ at Nantes told at first of enemy pressure and withdrawals, but latterly the situation became more confused. The French radio news distribution, right up to the last, glossed over the true state of affairs and was usually rounded off by encouraging speeches and appeals to the nation by ministers. They extolled the French army and encouraged the people to stand firm. Life at Nantes seemed to be going on very much the same as in peacetime; there was little attempt at blackout and cars used headlamps at night!

Towards the end of the week I went to the local HQ and , as I went up the drive, I noticed that smoke was issuing from the chimneys and a party was burning papers at the side of the house! This looked ominous enough – I had seen the same thing before earlier in the campaign. The Commander told me that things were pretty bad and that he could not say more at the moment but he was obviously a worried man.

As I was leaving the building, I met an acquaintance who rather shocked me; firstly by telling me that he knew the purpose of our mission, which was a closely guarded secret, and secondly that he felt it was his duty to tell me that the French were about to conclude an armistice. Apparently the British had been given a brief spell to effect a withdrawal from France. He volunteered the information that French resistance had almost ceased and the Germans were marching westwards practically unopposed. This put an end to the brief peaceful existence at Savenay. Before leaving I found the name and address of an RASC officer connected with petrol supplies who had an intimate knowledge of the local installations, and immediately set out to find him. The officer was run to earth at the Donges refinery just outside St Nazaire. At first he was, quite naturally loath to talk, but after having impressed upon him the serious implications and consequent dangers of these supplies falling into enemy hands, he put me ‘in the picture’ and cooperated fully. Time was pressing. To cut a long story short, a party was sent out to Donges immediately upon my return and demolition was timed for 9.00 p.m. that evening. Back at Savenay the remaining sections were getting ready to move to St Nazaire at midnight for, by this time, the order for general evacuation had been made for the remainder of British Forces in that part of France. They were tramping their weary way towards the roads leading to the port.

Plans were partly upset by a telephone call from a certain irate British general who forbade any action at either place! As I was speaking I could see the familiar red glow in the sky some miles away towards Blain and the black pall above the flames drifting slowly across the forest. I diplomatically didn’t mention this fact! Unfortunately I had no alternative but to send out an urgent message by dispatch rider to Donges which arrived just in time to cancel that demolition. There is no doubt that the enemy used this place, with its stocks of fuel oil, as a fuelling depot for submarines. When we heard the BBC news reports that the RAF had been over Donges we always had a pang of remorse – if only that dispatch rider had sustained a puncture or had ridden into a ditch! Our great consolation was that the BEF dump at Blain was destroyed, thanks to Peter Keeble’s timely initiative.

At midnight the party moved off towards St Nazaire. The going was difficult as will be imagined, for the roads were packed with troops. Some were on foot, others in transport ranging from many kinds of army vehicles to bicycles. RAF lorries were bringing in large numbers of ground staff. Nurses, doctors and, in fact, a fairly large cross section of the Expeditionary Force found themselves, at daybreak, converging upon that coastal town which was already packed with waiting troops.

I decided to leave one section behind under Second Lieutenant Paul Baker to carry out any final demolitions that the local commander might require including Donges if there was a change of heart. However no further demolitions were authorized as it was felt that it might hinder any possible French defensive action. The local commander sent this section back on 22 June on a collier already very heavily laden with troops that had hurriedly been pressed into service to help in the evacuation. The journey was uneventful and they made Falmouth in about twenty-four hours; relieved to have arrived back safely but incredibly hungry.

The large semi-circular bay with its wide sands, esplanade and ornamental public gardens was packed with the British Army to an extent that obliterated the natural colours and rendered the whole panorama a monochrome of khaki. Back in the town too, units of every description were either halted or moving at funereal pace back to the docks. Near the docks the scene changed to blue as the RAF were concentrating at this point. Far out in the bay, it seemed two or three miles away, were anchored several large transports with grey hulls shimmering in the sunlight, reflected from the placid blue sea.

All eyes were turned to those ships and we watched several small craft plying to and fro between the docks and the ships all day long. The embarkation staff worked wonders under difficult circumstances, keeping a steady control over the waiting thousands and, in cooperation with the naval authorities, performed miracles with the very limited facilities at their disposal. The men were good-humoured if not exactly patient, but frightfully sick at having to ‘leave it to Jerry’ as they expressed their feelings. Towards midday a single enemy plane flew over the town and harbour and reconnoitred the surging crowds below. There was no question of taking cover as there were too many of us. The usual alert was sounded and after the intruder had flown off in an easterly direction, the ‘all clear’ restored the former calm. Our party, except for the redoubtable Tommy Goodwin and his team of volunteers who had not yet arrived back from Honfleur, were put off during the afternoon to the Duchess of York with about 5,000 others packed like herrings. Every bit of alleyway, cabin, and between-deck space was filled.

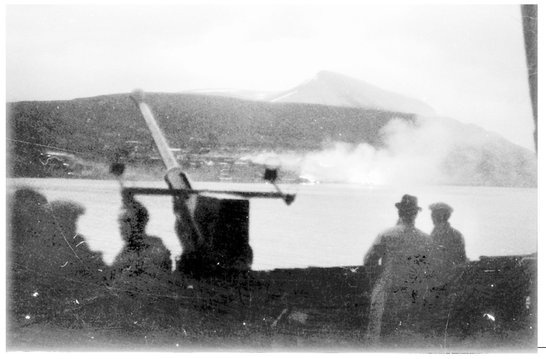

Soon after 3.00 p.m. the ship’s complement was full. As we lay at anchor in the sunny bay the tired troops quickly stretched out on every available bit of space and slept. About 4 .00 p.m. we were wakened by the liner’s ack-ack guns in action. It was a raid but without harm as the bombs fell wide of the mark, dropping some hundred yards or so astern. The other three waiting transports were equally fortunate. We remained at anchor in the bay for some hours before eventually leaving harbour, during which time the Hun plane came back with monotonous regularity, but always at great height.

Once under way, the voyage was uneventful. Food was scarce but in a couple of days we were landed at Liverpool.

When we arrived the Military Port Authorities had been ordered to send all the various ‘cap badges’ disembarking, who were from dozens of different units, straight to their regimental depots by train for sorting. At the outbreak of the war the sapper depot had been moved from Chatham to Halifax in Yorkshire. As we were more or less a complete formed body, I could not accept this. I went to the local bus depot and requisitioned sufficient buses to take us to London. The sappers were delighted as they had no wish to be herded off to the depot in Halifax. We stopped for a meal in Stafford on our way down and arrived at Charing Cross, the station for Gravesend, an hour or two after midnight. We were advised that an all night canteen was run by ladies in the crypt of St Martin-in-the-Fields in Trafalgar Square under the auspices of the Revd ‘Tubby’ Clayton of Toc H. When we got there at 3.00 a.m. they served us all with a wonderful traditional English breakfast. We then moved back to Charing Cross station where I left Peter Keeble in charge until I returned. I told him that I was going to Military Operations at the War Office firstly to report back and secondly to get permission to stand the unit down for seven days’ leave. He was to wait with the men until I got back.

The men were naturally exhausted and like all soldiers decided to lie down and rest all over the platform. A commuter train came in shortly and the passengers all took pity on our chaps and gave them half crowns to help them buy food. I got unexpectedly held up at the War Office and as a result several commuter trains came in in quick succession. The men were repeatedly given money by the generous hearted British public as each train emptied. Their pay being only two shillings a day, this was a bonus that they were not used to. At one point the Station Master told Keeble that he must move the men away but he stood his ground saying that they had strict orders to remain where they were. I eventually got back and we returned by the next train to Gravesend and all the men went on seven days’ leave much better off financially.

Goodwin and his party, despite their misgivings, had no difficulty getting back to Honfleur where they found everything very quiet, in fact there were still a few British Base troops there. The senior British Officer was a sapper lieutenant colonel and he took Goodwin under his wing and arranged for our men to be billeted in an empty RASC petrol depot. Regular meals were provided for the men in a restaurant. The town was nearly deserted and no air raids were being carried out by the enemy air force but German soldiers were clearly visible across the estuary in Le Havre. The party were in Honfleur nearly a week as the local commander saw no point in firing the oil tanks when they were not under any immediate threat of capture. Tommy Goodwin had prudently arranged for a fishing boat to be moored off the refinery that was victualled with tinned food and water from the petrol depot. When it had been evacuated considerable quantities of supplies had been left behind.

Perhaps the Germans had overrun their administrative chain and were forced to pause here on the Seine or it may have been that they knew that the French were negotiating terms for a cease-fire, after which they would be able to move down the French coast without any opposition. After a week, a large contingent of French Marines who had been ready to defend Honfleur pulled out without telling anyone. At this point Goodwin was told that he could fire the tank farm and he did so immediately.

Here he made a fateful decision. He decided that rather than going by fishing boat, which would be very vulnerable to attack from the air, they would sneak down along the coastal road through Caen to St Nazaire. His hunch proved correct as they met no German patrols at all and arrived back intact at their destination.

Though the majority of the fighting troops of the British Expeditionary Force were taken off at Dunkirk, large numbers of troops on the lines of communication of the British Army and nearly all the RAF ground staff fell back mainly on St Nazaire. The major part played by the ‘little ships’ in the Dunkirk evacuation is well known. Large numbers of pleasure craft, sailing barges and the like went over to the beaches to ferry men home. The evacuation at St Nazaire was a completely different problem. It was many miles from England, round Ushant and down the Bay of Biscay coast. Here only seagoing ships could be used. The Ministry of War Transport at short notice got hold of every available ship to help; liners, tramp steamers, colliers and, indeed, any ship capable of making the journey. As there was no shortage of small boats such as tugs and trawlers at St Nazaire to ferry troops it was decided that all shipping taking part in the evacuation would anchor out to sea. At this time of year the North Atlantic was still very cold.

When they arrived at St Nazaire they were embarked on the old Cunarder Lancastria which, with the others, was lying at anchor outside the port and suffering random bombing from the German Air Force. The men were fed and then bedded down in a hold. The officers and senior NCOs were placed, as far as possible, in cabins. The ship had been converted into a troopship with a capacity of 3,000 passengers. In the event because of the urgency of the situation the captain took on about 6,500 of which nearly 1,000 were civilian refugees. Suddenly there was a concerted attack by five Dornier bombers just as the ship was about to weigh anchor. The first bomb exploded in the number two hold in which there were around 800 RAF personnel. Another bomb went straight down the funnel which proved fatal to the ship. She began to settle and in a few minutes rolled over and sank rapidly. Of the 6,500 souls on board there were less than 2,500 survivors. Lance Sergeant Ward vividly described what happened next:

At about 3.15 p.m. we were awakened by alarm bells and we picked up the life jackets we found in the cabin and went out into the corridor which was full of senior NCOs and officers. Suddenly there was a distinctive crump and the ship began to list. Still no orders were issued, except by an American woman in uniform asking us to stand aside for women and children refugees, which we did.

We filed slowly out onto the deck, where I checked the lifeboats but found them lashed down and the turnbuckles rusted up. The ship was listing by then and some men were already in the water, which was being covered with oil. We could see an enemy plane still flying around the convoy but a destroyer thought to be HMS Highlander was sending up ack-ack and it was not possible to identify her positively. I can remember a soldier with a Bren gun on a mounting, maintaining fire until his tripod slipped over on the sloping deck. As the angle of list increased, I too decided to abandon ship and went over the side down a rope. I swam as hard as I could to get clear of the ship, and then trod water to decide my next move. I then found out why I was not so buoyant as usual – I was still wearing my steel helmet which I promptly jettisoned. I then heard somebody calling my name and found Lieutenant Whitehead and another man, who was not wearing a life jacket. I joined them and was asked to remove Lieutenant Whitehead’s trousers. This I achieved with some difficulty as he was wearing both belt and braces and still had his jack knife on a lanyard around his waist. We looked around, and decided to swim to a French fishing boat that was picking up survivors. I swam on my back with my right hand supporting the third man who could not swim. Lieutenant Whitehead acted as navigator and helped push us along.

I had a good view of the ship and also saw bombs drop into the sea near a destroyer. The ship turned right over, with men walking and sitting on her bottom. I could also hear survivors singing ‘Roll out the barrel’ and ‘There will always be an England’. When the ship was going under, we stopped swimming to allow Lieutenant Whitehead to see her go under. ‘I take a poor view of that’ was his comment.

After about an hour in the water, we eventually arrived at a French fishing craft where we were taken aboard. We were on this boat for some time, and the fit survivors were kept busy taking others up from the water. We tried artificial respiration on some bodies, but unfortunately, without success but it did serve to keep us warm. Early in the evening, we were all transferred to the SS Cronsay, which had also received a partial hit, which damaged her bridge and navigation equipment.

Goodwin, who was a strong swimmer and Sapper Mitchell were also picked up so eventually four of them returned to England; Goodwin, Whitehead, Ward and Sapper Mitchell. It was very sad that, having volunteered for yet another task, the others should have perished on the Lancastria.

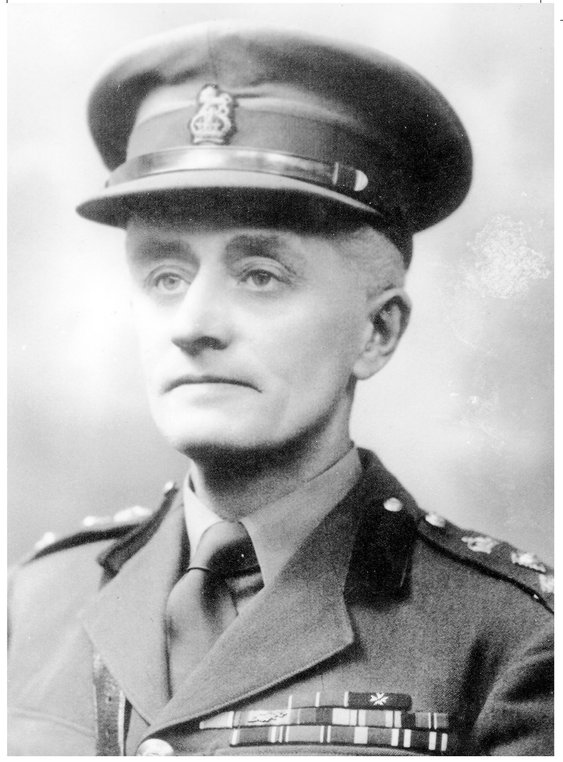

1. Brigadier C.C.H. Brazier in 1945.

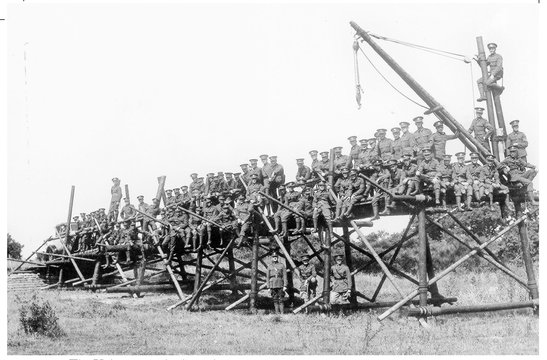

2. The Unit at camp in the early 1930s.

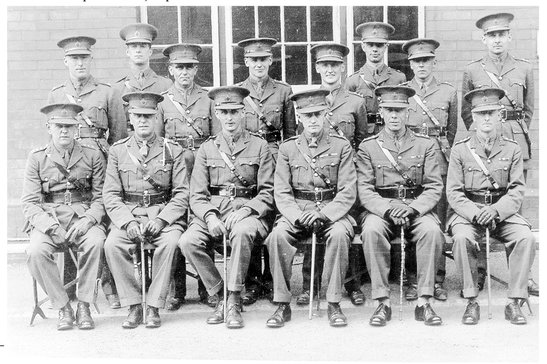

3. Officers in camp in 1937. Back Row: L to R: Lieutenant Hannam, Lieutenant Cox, Lieutenant Goodwin, Lieutenant Rear, Lieutenant Buxton, Lieutenant Dent, Lieutenant Keeble, Lieutenant Wilmot.

Front Row: L to R: Captain Hawes, Captain West, Captain Ewbank, Major Brazier, Captain Curtis, Captain Dawson.

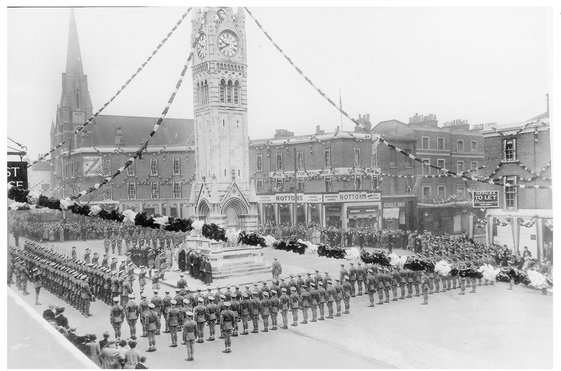

4. The Coronation Parade at the Clock Tower in Gravesend in 1937.

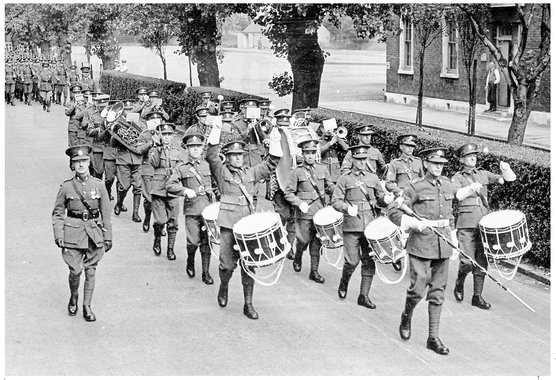

5. Kent Fortress Royal Engineers leaving the parade ground at Sheerness in 1938, headed by their own band.

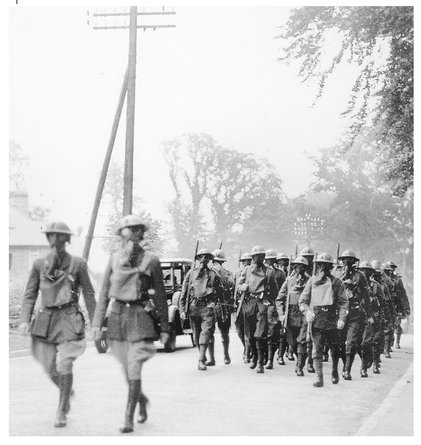

6. Route march wearing respirators; part of the toughening up process!

7. Construction of trenches. In those days great emphasis was placed on beating sandbags really square, like bricks.

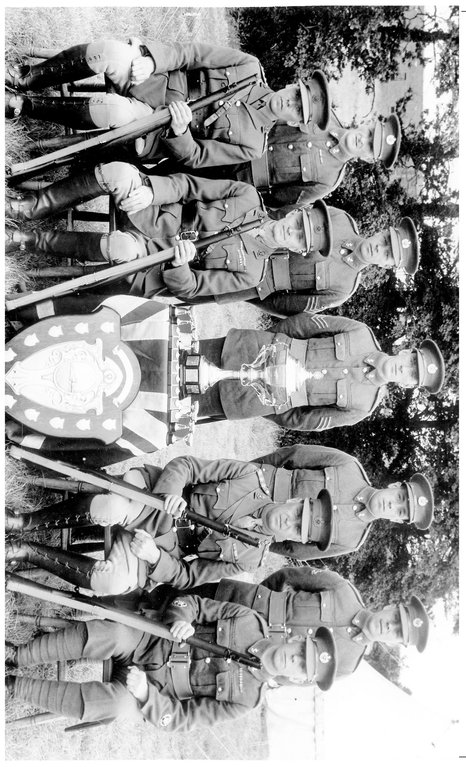

8. The winners of the Lord Wakefield Trophy in 1938. A real triumph for a small unit as it was shot for by all units in the Territorial army which, at that time, consisted of no less than ten division. Back row, L to R : Lance Corporal Gillet, Sergeant Halliday, lance Sergeant Smart, Sapper Kilbum, Sapper Mitten. Front row, L to R : Captain Keeble, Lieutenant colonel Brazier, Captain West, Sergeant Major Weeks.

9. Captain Peter Keeble.

10. Captain Tommy Goodwin.

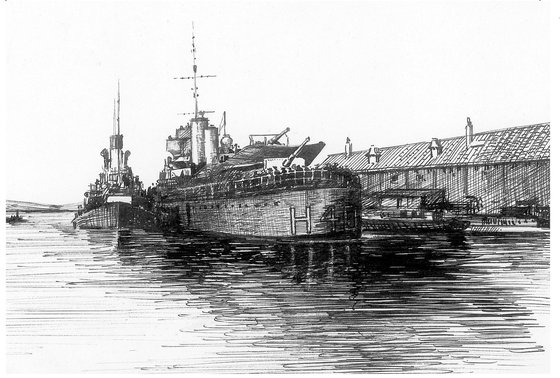

11. Landing at Ijmuiden.

Drawing by Lance Corporal Hill.

12. A burning oil wharf in Amsterdam.

Drawing by Lance Corporal Hill.

13. Lance Corporal Vic Hugget and Sapper Wally Page in Amsterdam. Having no cameras Hugget removed one from a civilian on the grounds that he was on a highly secret operation - hence this photograph and the following one, which are the only two to survive.

14. Burning oil tanks in Amsterdam.

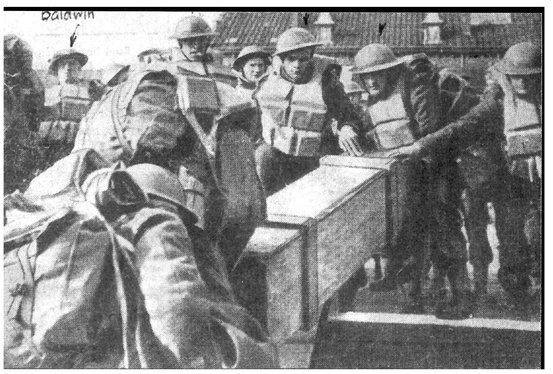

15. Sappers unloading stores at the Hook of Holland from HMS Wild Swan. This picture apppeared in a national newspaper the following day. It must have been taken by one of the ship’s company as there were no official photographers there. Much to the sappers’ chagrin it was headed ‘British Marines land stores in Holland’.

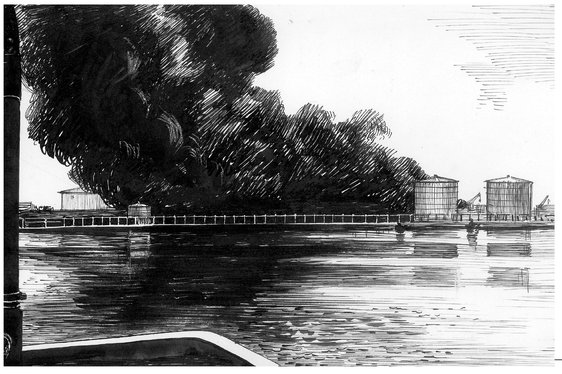

16. Rouen oil plants ablaze.

Drawing by Lance Corporal Hill.

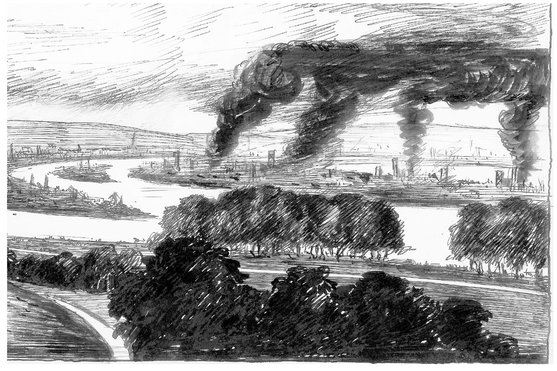

17. Courtesy of Imperial War Museum. Neg. C1804.

18. Courtesy of Imperial War Museum. Neg. C1802.

Chance photographs taken by a Coastal Command aircraft showing burning oil tanks at St Malo.

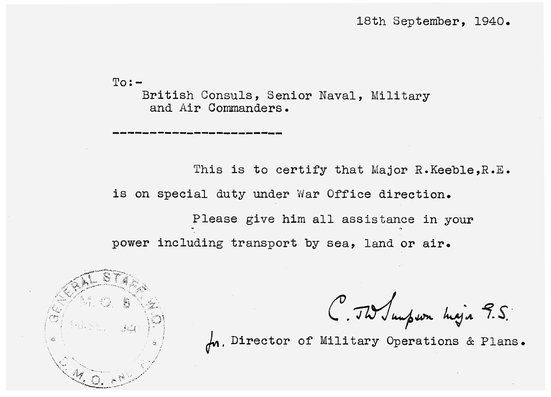

19. Major Keeble’s ‘magic letter’.

20. Destruction and withdrawal from Spitzbergen.

Courtesy of Imperial War Museum. Neg. H13592.

21. Courtesy of Imperial War Museum. Neg. H13604.

Destruction and withdrawal from Spitzbergen.

22. Courtesy of Imperial War Museum. Neg. H13600.

23. Ice floes.

Drawing by Lance Corporal Hill.

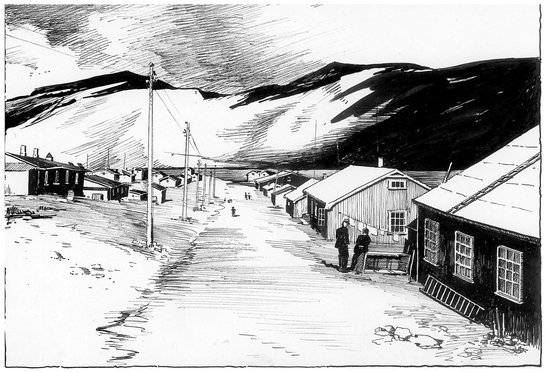

24. The Norwegian settlement of Longyearby.

Drawing by Lance Corporal Hill.

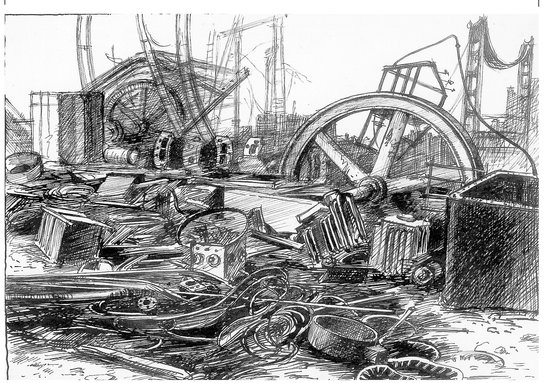

25. Demolition was carried out at Ny Alesund, Longyearby, Sveagruva, Pyramiden, Grumantby and Barentsburg.

Drawing by Lance Corporal Hill.

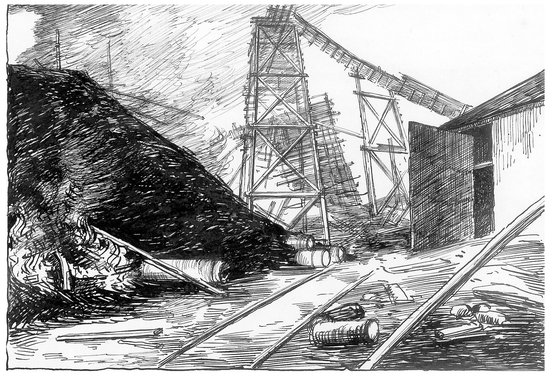

26. Coal stocks on fire.

Drawing by Lance Corporal Hill.

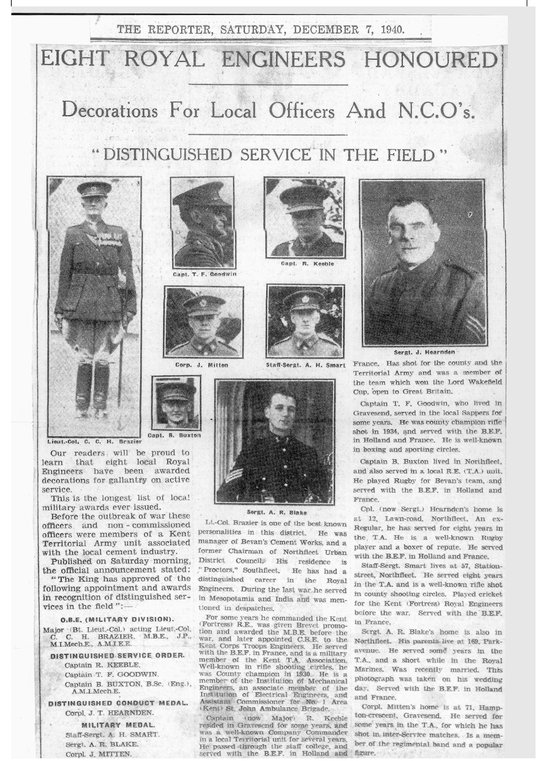

27. Honours and Awards. Cutting from the Gravesend and Dartford Reporter, 7 December 1940. See Appendix II for details.

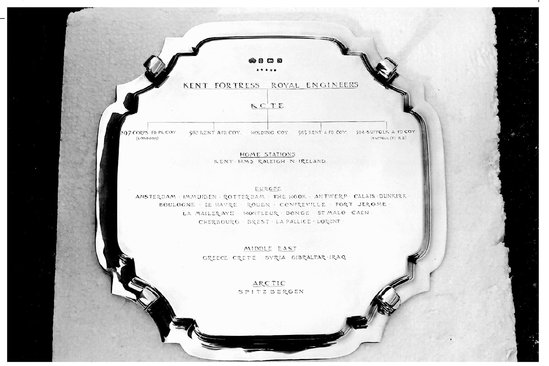

28. Salver presented to Clifford Brazier on giving up command. The reverse lists the remarkable number of places in which the Unit operated during the first two years of the war.

29. Survivors at a Sixtieth Anniversary party at Gravesend in May 2000. L to R: Albert Ashby, Ben Dowe, Alf Blake MM and Reginald Hicks.