Chapter Seven

DUNKIRK, CALAIS AND BOULOGNE

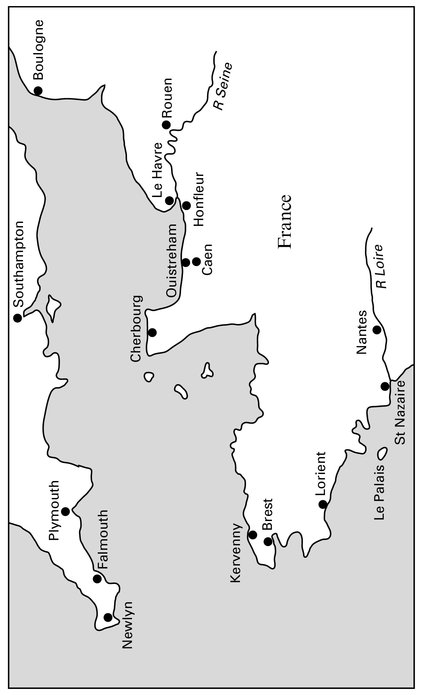

After we had deployed most of the unit onto the oil stocks on the Seine basin, Military Operations felt that it was perhaps worth tackling the smaller oil stocks at Dunkirk, Calais and Boulogne. The rear party at Gravesend, under Captain Bert West, was asked to provide sufficient sections to carry out these tasks. Not only did they leave Gravesend some time after we had left for France but they all returned before we did. On 23 May a section set off to Dunkirk on the destroyer Wild Swan with a naval demolition party. Bert West was in command of this section with Lieutenant Cyril Cox and about twenty other ranks. Commander Banks was in overall command of the combined demolition parties.

The situation, during these momentous days at Dunkirk, is vividly described by Cyril Cox:

As Wild Swan approached Dunkirk a dense volume of black smoke could be seen ascending into the air. A quick inspection through field glasses revealed an oil installation blazing furiously. West looked at Cox trying in vain to hide the chagrin he felt, but a further investigation led to the discovery of about twenty tanks close to the shore so far safe and sound. This was reassuring, and it was an eager and confident band of sailors and sappers that Wild Swan carried rapidly past a burning oil tanker and the forlorn wrecks of two destroyers and various other craft that surrounded the narrow entrance channel into Dunkirk. As the destroyer berthed along side the shattered quay, the rain came down in torrents and the poor visibility gave promise that the landing would be uneventful – but within five minutes the destroyer’s ack-ack guns roared forth and the sappers had their baptism lying in puddles of water.

West and Banks after explaining their mission were told to find themselves billets in Malo-les-Bains and ‘For Gods sake get these explosives off the quay’. Luck was in for the ground staff of a departing RAF squadron were only too pleased to get rid of their lorries, and with two deserted refugees’ cars, transport was assured. About three hours after landing quite a respectable convoy of two cars and five 3ton lorries moved away from the docks. Not a bad start!

. . . it was a beautiful day with light fleecy clouds, ideal for bombing and soon all three varieties, high, low and dive, were going on fairly continuously. West had a lucky escape when one side of his car was splintered as he got out of the other! About midday, a phenomenon occurred which has since become common place. A lone plane was seen describing a pretty white smoke ring in the sky, and as the men stood watching what he was up to, between fifty and sixty planes dived through and released their load. The air was filled with whistles and crashes, dense clouds of dust floated by, hardly had the first salvo ceased echoing when again the planes came through on their second run up; bricks and shrapnel flew about and the sappers and sailors were smothered in dust and rubble, all with 10 tons of TNT within a few yards – as a matter of fact some of the lads crawled under the laden lorries for cover! When eventually the noise and dust subsided, both sides of the street were quite flat and craters blocked the ends, but the hundred yards of road the party occupied were untouched, and the only casualties were one sailor badly bomb shocked and several cuts and bruises from flying debris.

A strange change came over the town during the day; when the party landed there was no organization or control, traffic went where it liked, crowds of unarmed French soldiers wandered about, officers, wounded or men who had lost their units milled around HQ awaiting instructions, everything was chaotic. Then as the British Army retired towards Dunkirk a few redcaps appeared and order came with them; ack-ack guns and men arrived and raced to take up positions to offer some opposition to the bombers. The ack-ack gunners were magnificent, it was hard to believe that men could become so weary and still keep going, each gun had only one team – sometimes less than one – but still they kept pegging away twenty-four hours a day.

By now the town was ablaze, order was unobtainable and food supplies were running out, streams of ambulances and Red Cross trains came onto the shattered quay, many peppered with machine gun bullets and shrapnel gashes, whilst the VADs and RAMC laboured unceasingly with their merciful tasks, hospital ship after hospital ship being loaded despite machine gunning and bombing and dispatched to safer waters.

Next day it became obvious that the destruction of the oil storage tanks was unnecessary. The leaping flames and great volumes of smoke bore evidence that the enemy’s bombs had found their mark, and Captain West placed his party at the disposal of the Commander RN. That day charges were placed in locks and cranes and by the evening all was ready, and the demolition party retired to a lighthouse, where, wonder of wonders water was obtainable from a well. Thirsts were slaked and empty water bottles refilled – a real piece of good luck.

One fact began to make itself obvious. Before long the quays and docks would become untenable, the Hun had the range only too well and knew just when to release his bombs to hit the target. It must have been about this time that the decision to use the beaches was taken and the necessary preparations set in hand.

Next day the first of the British Army began to arrive, and it was great to see the high spirits of the men tired as they were, and that every man still carried his weapon; there was no demoralisation here, everything seemed orderly and correct, at any rate at that early time.

Later that day Commander Banks decided that owing to the shortage of food and water the RE party should be evacuated right away. He refused to consider their eagerness to remain and assist him and sent them aboard a small drifter already packed solid with men. Hardly was the drifter ready to move away when down came three Messerschmitts and sprayed them with machine gun fire. Slowly the little ship gathered way and left the shattered town of Dunkirk, the flames of a hundred fires leaping skywards with the smoke joining into a black pall overhead. As they steamed towards England the watchers on the ship could see relays of bombers flying in over the smoke clouds and hear the roar of exploding bombs.

As Bert West succinctly put it after they returned:

The position was somewhat ludicrous. We were busy trying to destroy the oil stocks to prevent the Germans getting them. The Germans were bombing them to prevent the French and ourselves getting them and the French Fire Brigades were trying to put out the fires started by the German bombs!

At the same time as the Dunkirk venture another section under Second Lieutenant Arthur Barton was sent to Calais. This was a disappointing job as the party was unable to get anywhere near to the oil tanks because there was heavy fighting already taking place. Fortunately the amount of fuel involved at the tank farm was not great. The party returned safely to Dover.

Another party was sent to Boulogne under Captain Bernard Buxton. When they arrived there was heavy fighting just outside the port. The intelligence was wrong as there were no oil stocks. At this stage the destroyers that came in were only taking off casualties. The party helped to prepare two bridges on the actual approaches to the harbour for demolition. They were continually bombed, shelled and every now and then they came under sniper and machine-gun fire. Sadly Sapper Wells was very badly wounded. The French doctors did what they could for him in the First Aid post on the quay and he was evacuated by destroyer but died on the way to Dover. The party eventually got away on one of the last destroyers able to get into the port.

During the last twenty-four hours of the evacuation at Boulogne no less than fifteen destroyers came and went absolutely packed with troops. On one of these trips a destroyer was lying alongside the quay taking on exhausted soldiers when four German tanks came almost down to the quay. The crews on the destroyer with their 4.7-inch guns were ‘closed up’ for action against air attack. In a moment the ships’ guns engaged the tanks. The first shell missed, the second hit the first tank, ricocheted off, hitting the second tank and both were knocked out. The third shell hit the third tank fair and square and blew it to pieces and the fourth tank beat it.

This operation at Boulogne was officially described as abortive but Bernard Buxton summed it up well:

The blokes were all grand, all nine of them, and at least they had swapped shots with Jerry at one hundred and fifty yards range and may have killed some – who knows?’