9

The need for small blocks

CONDITION 2: Most blocks must be short; that is, streets and opportunities to turn corners must be frequent.

The advantages of short blocks are simple.

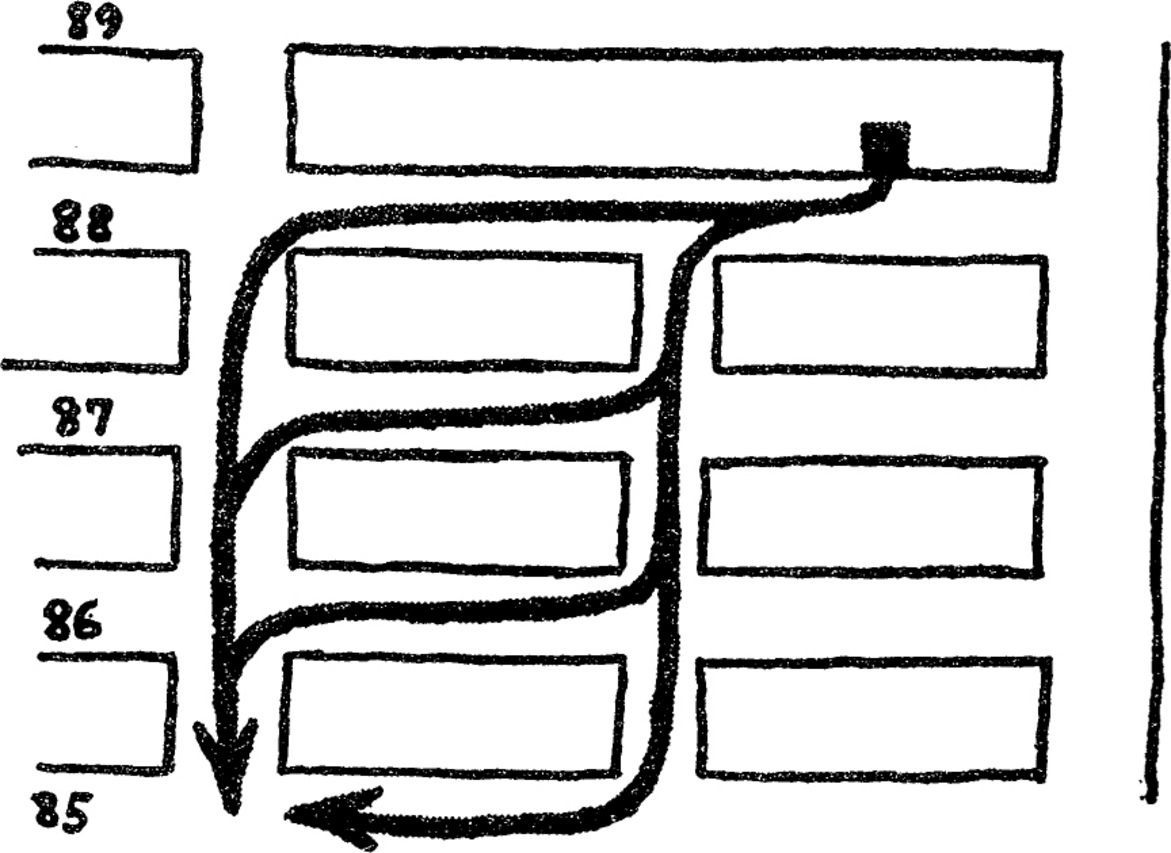

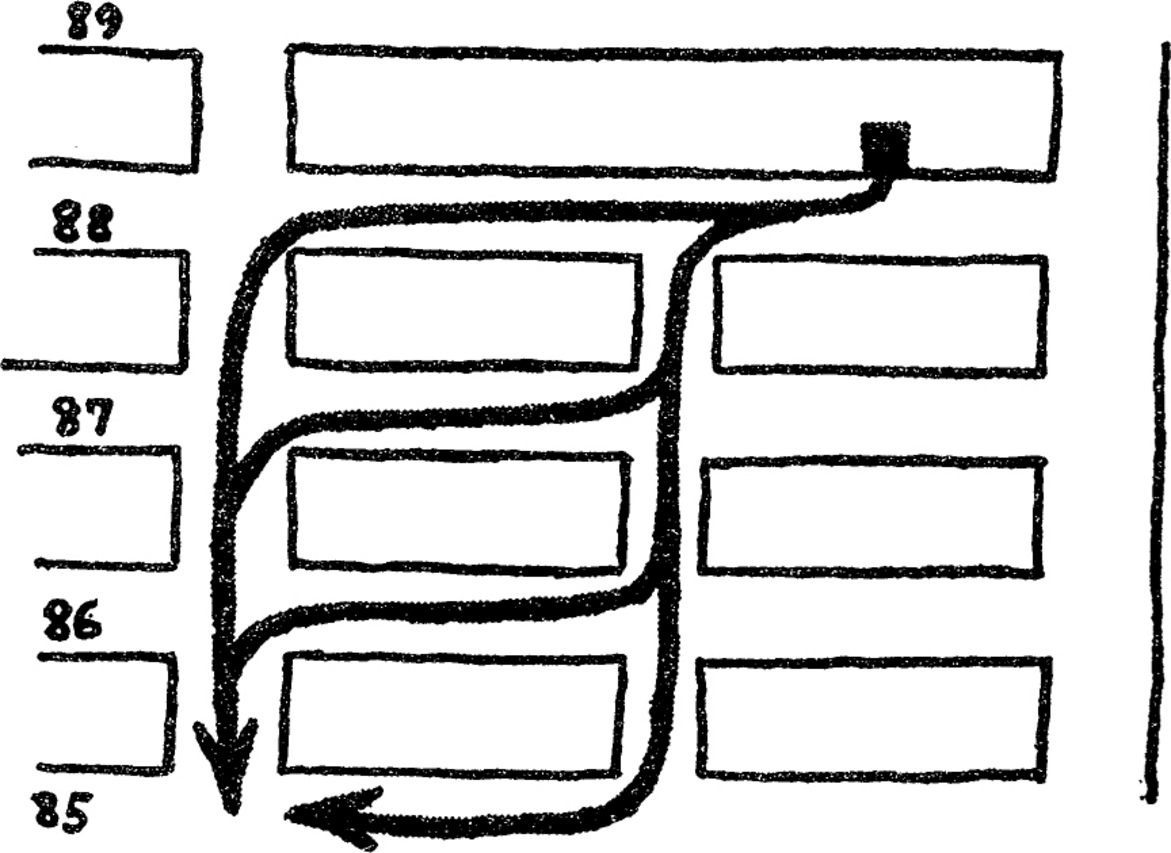

Consider, for instance, the situation of a man living on a long street block, such as West Eighty-eighth Street in Manhattan, between Central Park West and Columbus Avenue. He goes westward along his 800-foot block to reach the stores on Columbus Avenue or take the bus, and he goes eastward to reach the park, take the subway or another bus. He may very well never enter the adjacent blocks on Eighty-seventh Street and Eighty-ninth Street for years.

This brings grave trouble. We have already seen that isolated, discrete street neighborhoods are apt to be helpless socially. This man would have every justification for disbelieving that Eighty-seventh and Eighty-ninth streets or their people have anything to do with him. To believe it, he has to go beyond the ordinary evidence of his everyday life.

So far as his neighborhood is concerned, the economic effect of these self-isolating streets is equally constricting. The people on this street, and the people on the adjacent streets can form a pool of economic use only where their long, separated paths meet and come together in one stream. In this case, the nearest place where that can happen is Columbus Avenue.

And because Columbus Avenue is the only nearby place where tens of thousands of people from these stagnant, long, backwater blocks meet and form a pool of use, Columbus Avenue has its own kind of monotony—endless stores and a depressing predominance of commercial standardization. In this neighborhood there is geographically so little street frontage on which commerce can live, that it must all be consolidated, regardless of its type or the scale of support it needs or the scale of convenience (distance from users) that is natural to it. Around about stretch the dismally long strips of monotony and darkness—the Great Blight of Dullness, with an abrupt garish gash at long intervals. This is a typical arrangement for areas of city failure.

This stringent physical segregation of the regular users of one street from the regular users of the next holds, of course, for visitors too. For instance, I have been going to a dentist on West Eighty-sixth Street just off Columbus Avenue for more than fifteen years. In all that time, although I have ranged north and south on Columbus, and north and south on Central Park West, I have never used West Eighty-fifth Street or West Eighty-seventh Street. It would be both inconvenient and pointless to do so. If I take the children, after the dentist, to the planetarium on West Eighty-first Street between Columbus and Central Park West, there is only one possible direct route: down Columbus and then into Eighty-first.

Let us consider, instead, the situation if these long east-west blocks had an extra street cut across them—not a sterile “promenade” of the kind in which super-block projects abound, but a street containing buildings where things could start up and grow at spots economically viable: places for buying, eating, seeing things, getting a drink. With the extra street, the Eighty-eighth Street man would no longer need to walk a monotonous, al-ways-the-same path to a given point. He would have various alternative routes to choose. The neighborhood would literally have opened up to him.

The same would be true of people living on other streets, and for those nearer Columbus heading toward a point in the park or toward the subway. Instead of mutual isolation of paths, these paths would now be mixed and mingled with one another.

The supply of feasible spots for commerce would increase considerably, and so could the distribution and convenience of their placement. If among the people on West Eighty-eighth there are a third enough people to support a newspaper and neighborhood oddment place somewhat like Bernie’s around the corner from us, and the same might be said of Eighty-seventh and Eighty-ninth, now there would be a possibility that they might do so around one of their additional corners. As long as these people can never pool their support nearby except in one stream only, such distribution of services, economic opportunity and public life is an impossibility.

In the case of these long blocks, even people who are present in the neighborhood for the same primary reasons are kept too much apart to permit them to form reasonably intricate pools of city cross-use. Where differing primary uses are involved, long blocks are apt to thwart effective mixture in exactly the same way. They automatically sort people into paths that meet too infrequently, so that different uses very near each other geographically are, in practical effect, literally blocked off from one another.

To contrast the stagnation of these long blocks with the fluidity of use that an extra street could bring is not a far-fetched supposition. An example of such a transformation can be seen at Rockefeller Center, which occupies three of the long blocks between Fifth and Sixth avenues. Rockefeller Center has that extra street.

I ask those readers who are familiar with it to imagine it without its extra north-south street, Rockefeller Plaza. If the center’s buildings were continuous along each of its side streets all the way from Fifth to Sixth Avenue, it would no longer be a center of use. It could not be. It would be a group of self-isolated streets pooling only at Fifth and Sixth avenues. The most artful design in other respects could not tie it together, because it is fluidity of use, and the mixing of paths, not homogeneity of architecture, that ties together city neighborhoods into pools of city use, whether those neighborhoods are predominately for work or predominately for residence.

To the north, Rockefeller Center’s street fluidity extends in diminished form, as far as Fifty-third Street, because of a block-through lobby and an arcade that people use as a further extension of the street. To the south, its fluidity as a pool of use ends abruptly along Forty-eighth Street. The next street down, Forty-seventh, is self-isolated. It is largely a wholesaling street (the center of gem wholesaling), a surprisingly marginal use for a street that lies geographically next to one of the city’s greatest attractions. But just like the users of Eighty-seventh and Eighty-eighth streets, the users of Forty-seventh and Forty-eighth streets can go for years without ever mixing into one another’s streets.

Long blocks, in their nature, thwart the potential advantages that cities offer to incubation, experimentation, and many small or special enterprises, insofar as these depend upon drawing their customers or clients from among much larger cross-sections of passing public. Long blocks also thwart the principle that if city mixtures of use are to be more than a fiction on maps, they must result in different people, bent on different purposes, appearing at different times, but using the same streets.

Of all the hundreds of long blocks in Manhattan, a bare eight or ten are spontaneously enlivening with time or exerting magnetism.

It is instructive to watch where the overflow of diversity and popularity from Greenwich Village has spilled and where it has halted. Rents have steadily gone up in Greenwich Village, and predictors have regularly been predicting, for at least twenty-five years now, a renascence of once fashionable Chelsea directly to the north. This prediction may seem logical because of Chelsea’s location, because its mixtures and types of buildings and densities of dwelling units per acre are almost identical with those of Greenwich Village, and also because it even has a mixture of work with its dwellings. But the renascence has never happened. Instead, Chelsea languishes behind its barriers of long, self-isolating blocks, decaying in most of them faster than it is rehabilitated in others. Today it is being extensively slum-cleared, and in the process endowed with even bigger and more monotonous blocks. (The pseudoscience of planning seems almost neurotic in its determination to imitate empiric failure and ignore empiric success.) Meantime, Greenwich Village has extended itself and its diversity and popularity far to the east, working outward through a little neck between industrial concentrations, following unerringly the direction of short blocks and fluid street use—even though the buildings in that direction are not so attractive or seemingly suitable as those in Chelsea. This movement in one direction and halt in another is neither capricious nor mysterious nor “a chaotic accident.” It is a down-to-earth response to what works well economically for city diversity and what does not.

Another perennial “mystery” raised in New York is why the removal of the elevated railway along Sixth Avenue on the West Side stimulated so little change and added so little to popularity, and why the removal of the elevated railway along Third Avenue on the East Side stimulated so much change and added so greatly to popularity. But long blocks have made an economic monstrosity of the West Side, the more so because they occur toward the center of the island, precisely where the West Side’s most effective pools of use would and should form, had they a chance. Short blocks occur on the East Side toward the center of the island, exactly where the most effective pools of use have had the best chance of forming and extending themselves.*

Theoretically, almost all the short side streets of the East Side in the Sixties, Seventies and Eighties are residential only. It is instructive to notice how frequently and how nicely special shops like bookstores or dressmakers or restaurants have inserted themselves, usually, but not always, near the corners. The equivalent West Side does not support bookstores and never did. This is not because its successive discontented and deserting populations all had an aversion to reading nor because they were too poor to buy books. On the contrary the West Side is full of intellectuals and always has been. It is probably as good a “natural” market for books as Greenwich Village and possibly a better “natural” market than the East Side. Because of its long blocks, the West Side has never been physically capable of forming the intricate pools of fluid street use necessary to support urban diversity.

A reporter for the New Yorker, observing that people try to find an extra north-south passage in the too-long blocks between Fifth and Sixth avenues, once attempted to see if he could amalgamate a makeshift mid-block trail from Thirty-third Street to Rockefeller Center. He discovered reasonable, if erratic, means for short-cutting through nine of the blocks, owing to block-through stores and lobbies and Bryant Park behind the Forty-second Street Library. But he was reduced to wiggling under fences or clambering through windows or coaxing superintendents, to get through four of the blocks, and had to evade the issue by going into subway passages for two.

In city districts that become successful or magnetic, streets are virtually never made to disappear. Quite the contrary. Where it is possible, they multiply. Thus in the Rittenhouse Square district of Philadelphia and in Georgetown in the District of Columbia, what were once back alleys down the centers of blocks have become streets with buildings fronting on them, and users using them like streets. In Philadelphia, they often include commerce.

Nor do long blocks possess more virtue in other cities than they do in New York. In Philadelphia there is a neighborhood in which buildings are simply being let fall down by their owners, in an area between the downtown and the city’s major belt of public housing projects. There are many reasons for this neighborhood’s hopelessness, including the nearness of the rebuilt city with its social disintegration and danger, but obviously the neighborhood has not been helped by its own physical structure. The standard Philadelphia block is 400 feet square (halved by the alleys-become-streets where the city is most successful). In this falling-down neighborhood some of that “street waste” was eliminated in the original street layout; its blocks are 700 feet long. It stagnated, of course, beginning from the time it was built up. In Boston, the North End, which is a marvel of “wasteful” streets and fluidity of cross-use, has been heroically unslumming itself against official apathy and financial opposition.

The myth that plentiful city streets are “wasteful,” one of the verities of orthodox planning, comes of course from the Garden City and Radiant City theorists who decried the use of land for streets because they wanted that land consolidated instead into project prairies. This myth is especially destructive because it interferes intellectually with our ability to see one of the simplest, most unnecessary, and most easily corrected reasons for much stagnation and failure.

Super-block projects are apt to have all the disabilities of long blocks, frequently in exaggerated form, and this is true even when they are laced with promenades and malls, and thus, in theory, possess streets at reasonable intervals through which people can make their way. These streets are meaningless because there is seldom any active reason for a good cross-section of people to use them. Even in passive terms, simply as various alternative changes of scene in getting from here to yonder, these paths are meaningless because all their scenes are essentially the same. The situation is the opposite from that the New Yorker reporter noticed in the blocks between Fifth and Sixth avenues. There people try to hunt out streets which they need but which are missing. In projects, people are apt to avoid malls and cross-malls which are there, but are pointless.

I bring up this problem not merely to berate the anomalies of project planning again, but to indicate that frequent streets and short blocks are valuable because of the fabric of intricate cross-use that they permit among the users of a city neighborhood. Frequent streets are not an end in themselves. They are a means toward an end. If that end—generating diversity and catalyzing the plans of many people besides planners—is thwarted by too repressive zoning, or by regimented construction that precludes the flexible growth of diversity, nothing significant can be accomplished by short blocks. Like mixtures of primary use, frequent streets are effective in helping to generate diversity only because of the way they perform. The means by which they work (attracting mixtures of users along them) and the results they can help accomplish (the growth of diversity) are inextricably related. The relationship is reciprocal.

* Going west from Fifth Avenue, the first three blocks, and in some places four, are 800 feet long, except where Broadway, on a diagonal, intersects. Going east from Fifth Avenue, the first four blocks vary between 400 and 420 feet in length. At Seventieth Street, to pick a random point where the two sides of the island are divided by Central Park, the 2,400 linear feet of building line between Central Park West and West End Avenue are intersected by only two avenues. On the east side, an equivalent length of building line extends from Fifth Avenue to a little beyond Second Avenue and is intersected by five avenues. The stretch of East Side with its five intersecting avenues is immensely more popular than the West Side with its two.