CHAPTER TWELVE

Atonement

This book is dedicated to Dr. David Bakan and Professor Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, two men who have been instrumental in reintroducing psychoanalysis to its Jewish roots. Bakan (1921–2004) was one of the founders of humanistic psychology.1 He wrote on a wide variety of topics including psychoanalysis, religion, philosophy, and research methodology. His interest in the Jewish origins of psychoanalysis was aroused by his grandfather who spent hours reading him tales of the hassidim, especially by the Sassover Rebbe, Moishe Leib, who insisted that whoever does not devote one hour a day to himself is not a person and that to help someone out of the mud, one must be willing get into mud oneself.2

Bakan’s hypothesis is that Freud, consciously or unconsciously, secularized Jewish mysticism and that the origins of psychoanalysis exist within the Kabbalah (ibid., p. xi). He further stated that the discipline that Freud originated is essentially a contemporary version of this outlook, or should we say, “in-look”. I have already presented considerable evidence for this conclusion from the works of earlier Kabbalists like Abraham Abulafia, Moses De Leon, Isaac Luria, and Chaim Vital as well as modern thinkers like the Lubavitcher Rebbes, Aryeh Kaplan, Yitzchak Ginsburgh, and Adin Steinsaltz.

Bakan points out these thinkers were strongly influenced by the ideas expounded by the twelfth-century Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides, in his The Guide for the Perplexed.3 Bakan emphasizes that The Guide is essentially a handbook for the interpretation of dreams and visions. In doing so he recalls the Torah (Numbers 12: 6–8) “… if there be a prophet among you, I (God) … make Myself known to him in a vision, I do speak to him in a dream” (op. cit., p. xxv).

Maimonides (aka the Rambam) noted that the “keys” to interpretations of dreams and other phenomena lie in playing close attention to word play and anagrams as well as the operations of the “imaginative faculty” (ibid., p. xxv). According to the Rambam this faculty explains the difference between philosophers and prophets. Only the latter can appreciate the essence of the Divine, which is to create something from nothing. Concomitantly, the human wish to do likewise is very powerful and occurs through the metaphor of sexual intercourse (what the Rambam called mubashara). This is a further key to understanding the importance of sexuality and sexual imagery in human relations, a major focus of Freud’s conceptions (ibid., p. xxvi).

Bakan was the first scholar to systematically explore the links between psychoanalysis and the Jewish mystical tradition and, by extension, to Judaism itself. But there was one element in his exposition which I found hard to accept. That is the idea that Freud was a secret Sabbatean, or follower of the seventeenth-century mystic, Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676), a Sephardi rabbi and Kabbalist. Zevi preached during a period of murderous pogroms unleashed by the Cossacks against the Jews of eastern and central Europe. A large percentage of them were killed. Those that survived lived in terror and desperation.4 Zevi argued that their suffering was a prelude to the coming of the Messiah, when peace and prosperity would reign. To bring this about, he advised his brethren to abolish their sacred rites and rituals. Accordingly, fast days became feast days, morality became amorality, and prior bounds of sexuality were broken (he married a prostitute). Eventually Zevi proclaimed himself the Messiah and prepared his tens of thousands of followers to march to Jerusalem.5

On the way he stopped in Istanbul. The sultan, Mehmed IV, got word of Zevi’s plans and had him imprisoned. Later he was given the choice of converting to Islam or being impaled. Zevi chose to convert. This act devastated his devotees many of whom refused to believe in his apostasy.6 They thought it was part of the Messianic scheme. But it was a wrenching moment for the whole of world Jewry and was a major reason why the Hassidic revolution, which the Baal Shem Tov initiated a generation later, was so reviled.7

But on rereading Bakan’s book, I was struck both by the extent of his sources linking psychoanalysis and Kabbalah (which would have been even stronger if he had had access to the more recent accounts of Emanuel Rice and Marianne Krüll), and the reasons for Bakan associating Sigmund Freud with Sabbatai Zevi. Both men sought to repair the world. With Zevi this was the Jewish world, under threat of physical and spiritual annihilation. With Freud this was damaged souls or selves, Jewish or non-Jewish, and by extension, the world of social relations. Both focused on the freer expression of sexuality, and sought to break the bounds of normality. For Zevi this related to Rabbinic Judaism and with Freud this had to do with the stifling conventions of bourgeois propriety, which forswore the impact of infantile impulses on adult development. And they both saw themselves as Messiahs, Zevi leading Jews to the promised land, and Freud uncovering the unconscious bases of human life, especially the Oedipus complex.

Yet, Zevi was never able to overcome an overgrown ego. He was as much a showman as a Kabbalist. And because he converted to Islam, he became known as the “false Messiah.” Freud never converted to Christianity, “the royal road to social acceptance,” although numerous disciples did. He remained a proud Jew and keenly aware of the dagger of anti-Semitism.8

Professor Yosef Yerushalmi (May 1932–December 2009) is the second person to whom this book is dedicated. He was the most outstanding Jewish historian of the post-Holocaust era and held the Salo Wittimayer Baron Chair of Jewish History, Culture and Society at Columbia University. His most important work (1996) had to do with distinguishing between history and memory. The former is concerned with the collective consciousness of a people and its inspirational power. Thus, in the Passover story, every Jew is enjoined to feel that he or she was personally present at the exodus from Egypt. The story becomes part of their consciousness and gives meaning to their lives.

In contrast, in the modern era, Yerushalmi pointed out that scholars have focused on factual memory, as if the only real and important aspects of retrospection are verifiable facts. Yerushalmi called this preoccupation “the faith of the fallen Jew” (Myers, December 2009). He argued that it caused the Jew (or, for that matter, any member of a particular culture), to be estranged from his essential past or future “hi-story.”

As a scientist and archeologist of the mind Freud seemed to have had a foot in both perspectives. His seduction theory aimed to uncover specific events that led to neurotic traits. And in the elaboration of the Oedipus complex he was also concerned with distinct conflicts that might account for specific symptoms. Yet he also held a wider view of the mythological and multigenerational jealousies and desires that surfaced in any given individual. That did, of course, include himself. Indeed, he relied on his own experiences to develop general ideas about human relations.

Then we must consider, if psychoanalysis can be seen as a secular expression of Kabbalah, did Freud have to be a Kabbalist, or a Sabbatean, or, for that matter, a mystic to work out his ideas? The answer is: not necessarily. As a Galicianer Jew coming from a Hassidic family steeped in Hassidic and mystical lore, the ideas were “in the air.” As Yerushalmi would say, they were part of his “hi-story,” whether Freud acknowledged this or not.

Bakan concurred. He emphasized that it did not matter whether Freud was formally conversant with Kabbalistic literature in order to conclude that he was influenced by it. However, Bakan (op. cit., p. xx) also referred to the meeting of the Hassidic savant, Rabbi Chaim Bloch, with Freud. Bloch told Bakan that he saw a copy of the French translation of the Zohar in Freud’s library as well as other books on Kabbalah in German.9 Besides, in his discussions with Wilhelm Fliess, Rabbi Safran, and others, Freud showed that he was familiar with Talmudic and Hassidic ideas.10

These concepts were part of his heritage. Whether they contributed to his genotype, or genetic inheritance, is a moot point. Freud himself believed in the Lamarkian idea that acquired characteristics can affect and be passed on through the genes, a view that many researchers do not now accept. Certainly it coincided with his phenotype, or cultural inheritance which included his identifications with family and friends as well as everything he heard or saw.11 This was quite extensive (hence his awareness of Jewish customs and concepts) as Freud had a phenomenal memory, and, as is well known, he lived among and was mostly comfortable with fellow Jews.12

Yerushalmi was fascinated by Freud’s last major work, Moses and Monotheism (1939a, op. cit.), which many people took to be a scandalous attack on Jewish history and culture. Freud began writing it in 1934 and completed the narrative after he moved to London in 1938. A half century later, Yerushalmi responded with a detailed study, Freud’s Moses: Judaism Terminable and Interminable (1991, op. cit.), in which he queried Freud’s facts, but also the criticisms that engulfed the book. Yerushalmi asserts that the “true axis” of the publication is not the sensational idea that Moses was an Egyptian, nor that the Jews killed him, rather it lies in the down-chaining of tradition.

Moses received the Torah from Sinai and delivered it to Joshua, and Joshua to the Elders, and the Elders to the Prophets, and the prophets delivered it to the Men of The Great Synagogue. (Yerushalmi, 1991, op. cit., p. 29)13

The extended tradition (think of the eponymous song from the musical, Fiddler on the Roof) is what has given Judaism its “extraordinary hold” on the Jewish people. It is an experience that has gotten under and into their skin. As Yerushalmi underlines, Freud’s account is based on a “Lamarckian assumption” that underlies the transmission of Judaism from the individual to the group and back again. He insists that this train of events is related to what Freud called “the return of the repressed,” and is the “essential drama” of Freud’s work, an astonishing story of “remembering and forgetting.”14

Yerushalmi began his analysis of Moses and Monotheism with a joke, one that Freud told his colleague Theodor Reik, in 1908:

The boy Itzig is asked in grammar school: “Who was Moses?” and answers, “Moses was the son of an Egyptian princess.” “That’s not true,” says the teacher. “Moses was the son of a Hebrew mother. The Egyptian princess found the baby in a casket.” But Itzig answers: “Says she!” (1991, op. cit., p. 1)

Then, to explain the joke, Yerushalmi deploys the delicious phase, the “hermeneutics of suspicion,” which echoes Freud’s own doubts about Moses’s identity. Who was Moses? But, by the same token, who was Freud?

Yerushalmi seems to be sympathetic to Freud’s quest. He senses it is part of Freud’s struggle with his own origins. Is he really “a godless Jew,” as he so often proclaimed? Or, is he a mutant example of Judaeus Psychologicus, the Psychological Jew, whose vestigial traits include a fondness for Levy’s rye bread? Freud himself said that his book on Moses was akin to a “family romance,” an “historical novel,” which allowed him to utilize divergent perspectives about his monotheistic roots (ibid., pp. 5, 16–18).

Freud relied on the theses of the German theologian, Ernst Sellin (1867–1946). After studying the Prophet Hosea (who preached five centuries after Moses), Sellin concluded that Moses was an Egyptian, because he had an Egyptian name, and that he had been martyred by his own people who hated his tyrannical leadership (1922, pp. 25, 149). Freud also surmised that Moses had tried to impose on his followers the monotheistic cult of Aton, practiced by pharaoh Amenotep IV (as well as the Egyptian custom of circumcision).

Afterwards, according to Sellin, Moses was “resurrected” by the fusion of his persona with the “Moses” who commanded the cult of the Midianite volcano god, Yahweh. All this led to the creation of monotheistic Judaism. Meanwhile, Freud insisted on the Lamarckian predilection that the ancient heritage of the Jews “comprises … memory traces of the experience of earlier generations” (ibid., p. 31). Yerushalmi observed that for Freud these lines carry “the oppressive feeling of the longevity and irremediability of being Jewish,” a Jewishness which he both loved, and felt was a terrible burden (ibid., p. 32).

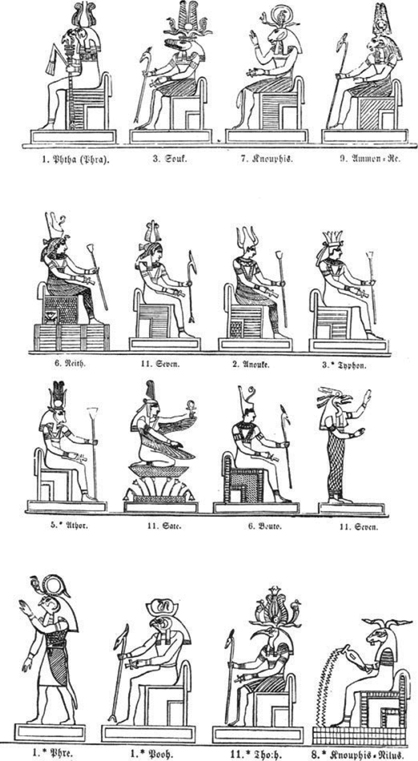

What astonishes Yerushalmi about Freud’s reconstruction of Jewish history is his recognition of “chosenness.” This idea is consistent with Freud’s postulating, as an essential fact of Jewish experience, the “return of the repressed.” That refers to the intense guilt about the oedipal slaying of Moses, the father figure who unveiled monotheism. Be that as it may, I think Freud’s guilt had more to do with the return of his Jewish feelings in the last decade of his life and the recognition of his deep attachment to his father. The bond included an intense interest in Egyptian antiquities. It is difficult to appreciate his lifelong passion for collecting statuettes of Egyptian deities without knowing that they were profusely illustrated in the Philippson Bible which Freud studied with his father for many years. The next two pages present a selection of these antiquities as published in this book.15

What seems to have happened is that Freud displaced his love for his father onto Egyptian antiquities and his conflicts with his father and grandfather onto the figure of the tyrannical Moses. Yet, Yerushalmi queries whether Jacob Freud is a useful example of an oppressive father. He says that a much better candidate would be Franz Kafka’s, father, Herman.16 Furthermore, he points out that Jacob Freud doted on his son.

[He] was a loving, devoted, warmhearted father who openly acknowledged his son’s precocious brilliance. (“My Sigmund has more intelligence in his little toe than I have in my whole head.”) Of course he also expected obedience and respect (we are still in the mid-nineteenth century), but he encouraged his son to surpass him and was proud of his achievements. (1991, op. cit., p. 63)

As for the illustrations in the Philippson Bible, Yerushalmi states that they would not necessarily have been seen by observant Jews at that time as a violation of the prohibition of graven images. Since the German-Hebrew text was completely acceptable for the Orthodox reader, it was clear that in this “modern” edition of the Bible, the pictures were only there to provide background information (ibid., p. 64).

Two further issues need to be clarified. The first is the claim that Moses was an Egyptian because he had an Egyptian name. This does not follow. People commonly take on the name of their adopted country without giving up their original identity. At the age of two, the child was given over by Yocheved, his mother and wet nurse, to Pharoah’s daughter who took him into her home as her son. She gave him the name Moses which, in Egyptian, means son. In contemporary terms she named him “Sonny.” The name could also convey “drawn from water,” for in Egyptian “mo” signifies water and “… uses” conveys, drawn from.17

The Torah establishes that Moses was the great-great-grandson of the patriarch, Jacob. “And Jacob begot Levi, Levi begot Kohath, Kohath begot Amram, and Amram begot Moses.” This family tree confirms his Jewish ancestry (Philippson, 1838–54).

Secondly Yerushalmi muses, “Return of the repressed? What was repressed?” In Judaism the murder of a man as important and famous as Moses would have been recorded and remembered throughout the generations, “eagerly and implacably, in the most vivid detail” (1991, op. cit., p. 85).

The biblical narratives of the sojourn in the wilderness do not hesitate to tell of constant rebellion by a stiff-necked and ungrateful people which, at one point, seems fully prepared to stone both Moses and Aaron [his brother] to death (Numbers 14:10). The prophets are by the irritating nature of their mission, always at risk. Jeremiah (chapter 26) is almost lynched in the Temple for treason … Zechariah son of Yehoiada the priest is stoned by order of King Joash (ll Chronicles 24:21) … All this is told unabashedly, without any sign of reticence. (ibid., pp. 84–85)

Figure 1. Egyptian gods, woodcuts from Philippson’s Bible, 1:869–871 (illustrating Deuteronomy 4: 15–31).

Figure 2. Egyptian temple, woodcut from Philippson’s Bible, p. 1164 (illustrating Hezekiah 8: 7–13).

Figure 3. Egyptian funeral ferry, woodcut from Philippson’s Bible, 2:459 (illustrating 2 Samuel 19: 17–20).

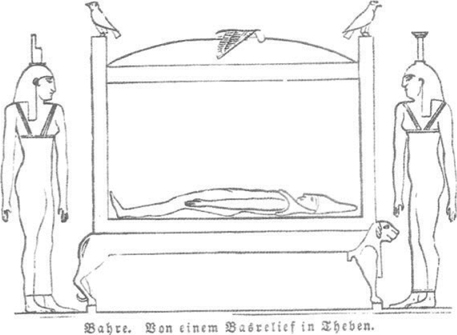

Figure 4. Egyptian funeral bier, woodcut from Philippson’s Bible, 2:394 (illustrating 2 Samuel 3: 31–35).

Yerushalmi continues that far from lying in the group unconscious, as Freud supposed, he overlooked what “was the most singular aspect of Jewish tradition from the bible onwards, to wit—its almost maddening refusal to conceal the misdeeds of the Jews” (ibid., p. 84). The murder of Moses could not have happened, and certainly not in the way that Sellin and Freud recounted it.

This brings us back to the essential drama of Freud’s life, forgetting and remembering, a repetition which occurred when he tried to deny his roots and become a Viennese professional. Nonetheless, the smell of a Jewish delicacy, or the sight of an anti-Semitic act, or the interjection of Yiddishisms and Hebrew into his writings, to cite but a few examples, constantly served to remind him of his origins.18

Indeed, Freud’s close friend and colleague, Hanns Sachs, noted in his affectionate memoir, Freud, Master and Friend, published not long after his death:

It is as though Freud walked intuitively and unconsciously in the footsteps of his ancestors and followed one of the most ancient Jewish traditions: the belief that all Jews, born or yet to be born, were present at Mount Sinai, that there they took upon themselves the “yoke of the Law.” (1944, p. 152)19

Try as he might, Freud could not escape from his lineage. Max Graf, who was the father of Freud’s famous patient, Little Hans, has described the formal rituals of the Wednesday Psychological Society, which eventually evolved into the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society:

First, one of the members would present a paper. Then black coffee and cakes were served; cigars and cigarettes were on the table and consumed in great quantities. After a quarter of an hour, the discussion would begin. The last and the decisive word was always spoken by Freud himself. There was an atmosphere of the foundation of a religion in that room. Freud himself was its new prophet who made the theretofore prevailing methods of psychological investigation appear superficial. Freud’s pupils—all inspired and convinced—were his apostles … However, after the first dreamy period and the unquestioning faith of his first group of apostles, the time came when the church was founded. Freud began to organize his church with great energy. He was serious and strict in the demands he made of his pupils; he permitted no deviations from his orthodox teaching. (op. cit., pp. 470–471)20

Graf’s observations fully accord with the picture I presented of his relationship with Stekel, Adler, and Jung, and later dissidents. Although a rebel himself from conventional views on infantile and adult development, he treated colleagues who did not agree with him as heretics and was quite willing to excommunicate them from the psychoanalytic community. This created a culture of conformity which has carried on today in analytic institutes where candidates are expected to “toe the line,” whether classical Freudian, Kleinian, Lacanian, or whatever.

Freud himself anticipated such “necessary” outcomes in his epic attack on organized religion, The Future of an Illusion (1927c, op. cit., pp. 5–58). He argued:

If you want to expel religion from our European civilization, you can only do it by means of another system of doctrines, and such a system would from the outset take over all the psychological characteristics of religion—the same sanctity, rigidity and intolerance, the same prohibitions of thought—for its own defense. (ibid., p. 51)21

One might think that Freud was prophetic in describing the future difficulties of the “psycho-analytical movement.” His official biographer, Ernest Jones, tried to counter the accusation that Freud had created a new “secular religion.” Yet, in his caricature, he seemed to give credence to the very idea that he was attempting to deny:

It was this element that gave rise to the general criticism of our would-be scientific activities that they partook rather of the nature of a religious movement, and amusing parallels were drawn. Freud was of course the Pope of the new sect, if not a higher Personage, to whom all owed obedience; his writings were the sacred text, credence in which was obligatory on the supposed infallibilists who had undergone the necessary conversion, and there were not lacking the heretics who were expelled from the church. (1959, p. 205)

Jones also mentioned that there was a “minute element of truth” in the “amusing” picture he portrayed. Indeed, if you substitute “Rebbe” for Pope, “hassidim” for new sect, “God” for high personage and “Bible” for sacred text, then you can find a fairly accurate description of the Hassidic milieu from which Freud emerged.

No matter how hard Freud tried to bury, or murder, his Galicianer self, it lay within his soul, if not his genes. For Freud, the “return of the repressed” was the recreation of a Hassidic “court” replete with a powerful, charismatic, omniscient Rebbe (akin to Moses, leading modern man to the promised land of psychological health), a Bible (his collected works), a multitude of attendants (his inner circle of friends and colleagues), and a formal structure of meetings and ritual (the Wednesday Society, later the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society). Thus, when Karl Abraham first attended one of these occasions, he reported to his friend, Max Eitingon:

He [Freud] is all too far ahead of the others. [Isador] Sadger is like a Talmud-disciple, he interprets and observes every rule of the Master with orthodox Jewish severity. (Gay, op. cit., p. 178)22

Although Freud did hope that psychoanalysis would give rise to a “secular priesthood,” he constantly sought to distinguish between religion and mysticism, of which he disapproved, and science, of which he approved. Freud wanted to be seen and treated as a scientist. In his early years he was very careful to deny that the discipline of psychoanalysis was a “Jewish science.” He thought that any link between his Jewishness and his creation would bring down the hatreds of anti-Semites on his head. This was an important reason for concealing his knowledge of Jewishness, in almost all its forms. Following this lead, his disciples did likewise. However, later in life, he remarked:

“I don’t know whether you’re right in thinking that psychoanalysis is a direct product of the Jewish spirit, but if it were I wouldn’t feel ashamed.” (Clark, op. cit., p. 242)23

The Hungarian Jewish neurologist Sândor Ferenczi (1873–1933) was the essential link between Freud, psychoanalysis, science, and Kabbalah. He decided to become a psychoanalyst after reading Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, and quickly became one of Freud’s closest disciples and collaborators (ibid., pp. 214–215). In 1909 he accompanied Freud and Jung to Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, where Freud delivered five lectures which introduced psychoanalysis to an American audience. Given the importance of this event in the history of the psychoanalytic movement, analysts tend to forget that the really famous speakers were not Freud and Jung, but the scientists Ernest Rutherford and A. A. Michelson, both of whom had recently won Nobel prizes in chemistry and physics respectively. Their work instigated the great discoveries in the twentieth century in relativity, atomic physics, and quantum theory.

No doubt the five men met and discussed psychology and meta-psychology, physics and metaphysics. Ferenczi was particularly fascinated by these subjects, even before he read Freud’s work. The physicist, Tom Keve, has described Ferenczi’s grappling with new paradigms in his paper, “Physics, Metaphysics, and Psychoanalysis.” As far back as 1899, Ferenczi announced that the predominant, old, rigid, materialistic, reductionistic model of human relations had to change. Keve points out Ferenczi proposed a holistic, integral world view twenty years before Jung and twenty-five years before quantum theory (ibid., p. 159).

Ferenczi followed up these ideas in the introduction to his 1923 study, Thalassa (Greek for sea or ocean), a forerunner of later psychosomatic studies such as Norman Brown’s Life Against Death. He wrote:

… the conviction grew in me, that an interpretation into the psychology of concepts belonging to the field of natural science, and into the natural sciences of psychological concepts, was inevitable and might be extremely fruitful. (Szekas-Weisz & Keve, 2012, p. 160)

Ferenczi also had an extensive network of familial and social relations with the most brilliant scientists and mathematicians of his generation. They included John von Neumann, Leo Szilard, Theodor von Kármán, Eugene Wigner, and Wolfgang Pauli Jnr. Many intermarried within each others’ families as well as with prominent psychoanalysts, a connection which Keve demonstrates in his book, Triad: the Physicists, the Analysts, the Kabbalists (2000, op. cit.).24 Von Neumann’s brother, Nicholas, recalls that the Ferenczis were neighbors:

(Sandor) was a close relative and member of the family circle. As a result, discussions about Freud and psychoanalysis were among the subjects frequently encountered around the dinner table. (ibid., p. 164)

Moreover, to an extraordinary extent, their ancestors were rabbis, Kabbalists, and purveyors of sacred texts. The grandfather of Wolfgang Pauli, Jacob Pascheles, was the elder of the Gipsy Synagogue in the old city of Prague, and his father, Wolf (Pauli’s great-grandfather), sold and published religious and mystical texts including the legend of The Golem (Keve, 2000, op. cit., pp. vi–vii).

Ferenczi’s circle included Gershom Scholem who, after leaving Germany to settle in Palestine, founded the modern study of the Kabbalah. Scholem was a close personal friend of Wolfgang Pauli and one can assume that he would often discuss gematria, the mystical significance of numbers, with him. One number, 137, is particularly important, for it is “the magic number in physics,” the inverse fine structure constant, and represents the strength of electromagnetic interaction (Keve, 2012, op. cit., p. 169).25

The Nobel laureate, Richard Feynman, who originated the theory of quantum electrodynamics, has confessed that the number 137 is one of the greatest mysteries in physics:

… All good theoretical physicists put the number up on their wall and worry about it … is it related to pi or perhaps to the base of natural logarithms? Nobody knows. It’s one of the greatest damn mysteries of physics: A magic number that comes to us with no understanding by man. You might say the “hand of God” wrote that number, and “we don’t know how He pushed his pencil.” (1985, p. 129)

Is it just a coincidence that the gematria, the numerical value of the Hebrew word Kabbalah, is 137? In the year 1295 Abraham Abulafia, founder of the school of prophetic Kabbalah wrote that “… the Kabbalistic way consists of an amalgamation in the soul of man of the principles of mathematical and natural science” (Szekas-Weisz & Keve, op. cit., p. 175). The statement echoed Ferenczi’s thoughts linking maths and mysticism, psychology and physics, six centuries later. In a paper entitled, “Mathematics,” published posthumously, he noted:

… armed with the tool of psychoanalysis, we must try to increase our understanding of one special talent—mathematics.

Mathematics is self-observation for the metapsychological processes of thought and action.

The mathematician appears to have a fine self-observation for the metapsychic processes, finds formulas for the operation in the mind … projects them onto the external world and believes that he has learnt through external experience. (ibid., p. 162)

Keve points out that these views reflect “the deep connections between quantum physics and mathematics on the one side and psyche or psychoanalysis on the other,” and lead directly to the idea of an observer created reality. Both the observer and the observed (such as therapist and patient) are one total system. “Hence the observer effects the observed and vice versa, so that—in a sense—one never knows what ‘really’ happened, or would have happened, if the observation had not been made” (ibid., p. 170).

A further implication is that consciousness and the material world are intrinsically connected. Man is not simply a distinct particle interacting with other particles, but also exists in the form of a wave which can spread out in all directions influencing a multiplicity of other beings. Perhaps a dim awareness of this situation leads to the admonition about being careful with one’s actions, as in: “Don’t make waves!”

The awareness of quantum reality led Eugene Wigner to propose that consciousness creates actuality, a view very close to a Kabbalistic understanding of the unfolding of the universe. In a reconstructed conversation between Ferenczi and his wife Gizella, Ferenczi exclaimed:

He [Jung] is right that psychoanalysis has been conceived out of mystical, Jewish tradition. It is the Kabbalah of the twentieth century. It is the Zohar transplanted to our age, adapted to our needs, modified by our observations. I said as much to Jung myself, years ago. Of course, Freud will not hear of it. (Keve, 2000, op. cit., p. 84)

The interconnection between the observer and the observed, the analyst and the patient, God and mankind, is a basic Kabbalistic as well as physical concept. Ferenczi utilized the idea in developing his technique of “mutual analysis,” whereby both the analyst and the analysand are seen as part of a single system, mutually affecting each other. He felt that the only way of disentangling the personal realities of the participants is to view it as a whole, and to focus on the operation of the system as a whole, not just on the individual involved in it. Freud alluded to this in his elaboration of the transference relationship. Klein and her colleagues greatly expanded systemic analysis by uncovering the role of the countertransference in the analytic relationship and, in particular, the actions of projection and introjection, projective identification and introjective identification.

But Ferenczi’s more active role with his patients led to Freud’s recriminations and subsequent break with him. A major issue was therapeutic abstinence. Freud emphasized the importance of remaining aloof from his patients while carefully listening to and encouraging their free associations. For Ferenczi this was treating people as particles. He was far more engaged with his patients, a technique of “action analysis” which allowed deeply denied thoughts and feelings to emerge, in the therapist as well as in the patient. This was the opposite of the analytic “blank screen,” but also carried with it the danger of over-involvement and making non-therapeutic waves. Nonetheless Ferenczi was a pioneer in working with very disturbed patients and an analyst who anticipated many of the concepts and techniques of modern psychotherapy.26

For many reasons, including his split with Freud and his terminal illness from pernicious anemia in the 1930s, Ferenczi died unappreciated and shunned by the psychoanalytic establishment (ibid., pp. 1–8). This began to change with the publication of his Clinical Diary (1988) and his correspondence with Freud. His professional resurrection is an overdue atonement for a psychoanalyst who was clearly ahead of his time, especially in the way he tried to integrate psychoanalysis, physics, and Kabbalah.

Once again, this raises the question, is psychoanalysis a Jewish science? The answer depends on how you define Jewish and how you define science. Freud tried to argue that it was not a Jewish science because he did not want it to be the focus of anti-Semitic enmity.

Let us first consider the issue of science. This involves a methodology which can be learned and objectively reviewed, such as when Freud dissected the testicle of an eel. But his far greater accomplishment was to develop a science of subjectivity, a sophisticated way of eliciting the internal life of men and women and children through the analysis of dreams, associations, slips of the tongue, and other inner to outer phenomena.27 Then we have to consider the founding fathers of psychoanalysis, their Jewish genealogies, and the huge proportion of analysts and therapists who, even today, have Jewish religious or cultural backgrounds. And, as Bakan and Yerushalmi have shown, the concepts and practices of psychoanalysis are deeply rooted in the conceptualizations and customs of Judaism and the Jewish mystical tradition. So yes, it is not difficult to conclude that psychoanalysis is a Jewish science.28

Freud’s daughter, Anna, made a reparation, a tikkun, an atonement, for her father’s and her own doubts about the Jewish nature of psychoanalysis in a speech which she wrote and which was delivered on his behalf on the occasion of the creation of the Sigmund Freud Chair of Psychoanalysis at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1977. She said:

During the era of its existence, psychoanalysis has entered into connexion with various academic institutions, not always with satisfactory results … It has also, repeatedly, experienced rejection by them, been criticized for its methods being imprecise, its findings not open to proof by experiment, for being unscientific, even for being a ‘Jewish science.’ However the other derogatory comments may be evaluated, it is, I believe the last-mentioned connotation which, under present circumstances, can serve as a title of honor. (Yerushalmi, 1991, op. cit., p. 100)

Indeed, by his last years, Freud had begun to soften his hostility to religious and spiritual phenomena. Thus, in 1930, he wrote to his friend, the French dramatist and writer, Romain Roland: “I am not an out-and-out skeptic. Of one thing I am absolutely positive, there are certain things we cannot know now” (Clark, 1980, op. cit., p. 496).29

In the same year his mother, Amalie, died at the age of ninety-five. Freud meticulously prepared her funeral and burial according to strict Orthodox Jewish standards. He arranged for the entire Freud family to attend, although he did not (Rice, op. cit., pp. 109–110). Just as his teenage friend, Eduard Silberstein, with whom he learned Spanish, noted, Freud never forgot a language, it is highly likely that he never forgot a custom (Clark, op. cit., pp. 21–22).

Likewise, Freud carefully prepared for his own passing. He had been suffering from cancer of the jaw for sixteen years, had endured many operations and, for much of the time, had been in great pain. By the time he moved to London in 1938, his condition had worsened, and by the fall of 1939, he realized that he could not carry on. Freud had an agreement with his personal physician Max Schur, to administer a terminal dose of morphine when requested (Gay, op. cit., pp. 739–740). He chose to exit the world on Saturday, 23 September 1939. This was not just the Sabbath, but it was also the most holy day in the Jewish calendar, Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, which itself is the culmination of ten days of introspection about one’s sinful thoughts and actions (Schneider & Berke, 2011, vol. 13, pp. 1, 9). Yerushalmi suggests that such soul-searching was the impetus for Freud’s writing Moses and Monotheism during his last decade (1991, op. cit, p. 6).

There are several Jewish primary sources that point to the special merit a person has when dying on the Sabbath and especially, Yom Kippur.30 The Talmudic references are well known to people who have grown up in religious or Hassidic homes as did Freud.

“The death of the righteous affords atonement” (Talmud, Moed Katan 28a).

Here “the righteous” refers to a person who has expressed a willingness to correct his faults. The commentators say that “the atonement” will come both for the deceased and those left behind (Schneider & Berke, 2011, op. cit., p. 12).

“Dying on Sabbath eve is a good omen … [and] on the termination of the Day of Atonement is a good omen.” (Talmud, Ketuboth 103b)

Freud died at 3:00 a.m. on the morning of Yom Kippur. According to the Talmud, dying on the Sabbath, the Day of Rest, is a good sign, for then the soul of the deceased will go immediately into Heaven. Dying on Yom Kippur is a good sign because repentance has begun.31

The prominent eighteenth-century Kabbalist Chaim Joseph David Azulai has added: “The Day of Atonement atones for even mental thoughts to change oneself” (2003, p. 271).32

Meanwhile, the Zohar (Book of Splendor) explicitly states that God is so compassionate that on Yom Kippur … no sins remain … that could grant the side of judgment (i.e., severity) dominion (2006, 1:229b, p. 384). In the period of the “Ten Days” (and before) Freud would have been able to make a review of his life history, literally an accounting of his soul (cheshbon hanefesh). That, in itself, would “qualify” him for a return to the fold, as a “believing Jew,” not a Jew who was “godless” or “estranged” (Schneider & Berke, 2011, op. cit., p. 14). As his colleague Karl Abraham wrote:

“… the Day of Atonement, whose liturgy begins with the somber sound of the Kol Nidre [hymn], speaking of heavy guilt, and ends with the proclamation of the uniqueness of the Lord.” (1920)

This soul searching must have been a strenuous mental and emotional effort. Yet, while it was going on, it seemed that Freud remained as recalcitrant as ever regarding ritual, for he directed that he would not be buried, according to the tradition which he well knew, but cremated, and his ashes placed in an 2,300-year-old Greek urn.

Perhaps, unsurprisingly, his wife, Martha, despite her positive feelings about religion and ritual, chose to be cremated and her remains were added to the urn when she died in 1951.

How ironical that sixty-three years later a thief tried to steal the urn where it was on display at the Golders Green Crematorium in north London. But he (or she) slipped while trying to make a getaway and the urn was badly damaged. The police did not mention whether any ashes had escaped (Doherty, 2014, p. 3).