1. Contemporary air photograph showing Yorke Beaches and Stanley Airport where the Argentine 2nd Marine Infantry Battalion landed.

In 1982, Goose Green was the largest settlement in the Falklands, its 127 settlers dependent on sheep farming. About 5 miles to the north is Darwin with about twenty-five inhabitants. Both settlements were serviced by an airstrip, which the Royal Engineer briefing map listed as 400 yard long and graded as ‘good, fairly firm’. The settlement had been occupied by C Company, 25th Infantry Regiment since 3 April. From air photographs, documents captured at Port San Carlos, a 25th Infantry Regiment prisoner, the Cable and Wireless telegram intercepts and reports from a G Squadron patrol overlooking the settlement from the east, HQ 3 Commando Brigade had good intelligence on Goose Green. The defence of Goose Green was built around the 643 men, mostly conscripts, of the 12th ‘General Arenales’ Infantry Regiment, which had arrived on 28 April with three missions:

Provide a reserve battle group, known as Task Force Mercedes, to reinforce Army Group, Stanley.

Occupy Goose Green.

Defend Military Air Base Goose Green.

The Military Air Base (Air Commodore Wilson Pedrozo) housed four 7 Counter Insurgency Squadron CH-47 Chinook helicopters and, from 29 April, twelve aircraft of the Pucara Squadron Falklands. Shortly after daybreak on 1 May, in what turned out to be a fortuitous move, Pedrozo ordered the CH-47s to be parked in the settlement. Although several civilian and non-operational aircraft were dispersed around the airstrip to deceive British air photo analysts after three 800 NAS Sea Harriers destroyed a Pucara and damaged two others, Pedrozo declared the base non-operational. He censured Captain Braghini’s gunners for not being alert. Using the excuse of ensuring their safety, Pedrozo confined the settlers to the Community Centre. Three days later, Braghini’s gunners, alerted by the early warning radar at Stanley, shot down Lieutenant Taylor’s Sea Harrier, which slewed to a standstill near the eastern perimeter of the airfield.

The main defence line stretched across the isthmus from Darwin Ridge to the ruins of Boca House and was defended by A Company (First Lieutenant Jorge Manresa). In depth, covering the approaches from Lafonia was C Company (Second Lieutenant Ramon Fernandez). Recce Platoon (Lieutenant Morales) provided a screen. In reserve was a composite platoon raised from HQ Company (Second Lieutenant Ernesto Peluffo). 7th Platoon, C Company, 8th Infantry Regiment (Second Lieutenant Guillermo Aliaga) covered Salinas Beach. C Company, 25th Infantry Regiment (Lieutenant Esteban) minus Combat Team Eagle, remained at the Schoolhouse. The artillery was provided by A Battery, 4th Airborne Artillery (First Lieutenant Carlos Chanampa). Two Pack Howitzers were being ferried to Goose Green on the Coastguard cutter Rio Iguazu when it was attacked in Choiseul Sound by two Sea Harriers on 22 May with one gun damaged beyond repair. The remaining two arrived from Stanley by helicopter. In addition there were the two 35mm Oerlikons and six Air Force Rh-202 20mm cannon defending the airfield. Two Air Force School of Military Aviation security companies defended the western beaches.

Piaggi was an experienced soldier, however, under command he had troops from three regiments from two brigades from different corps, none of whom had ever worked together and varied in quality. His support weapons were left in Argentina after the Ciudad de Cordoba hit rocks and was then stranded by the imposition of the TEZ. He had one 105mm recoilless rifle with A Company and of ten 81mm mortars, eight were damaged. He was short of radios and the loss of B Company (Combat Team Solari) to the Reserve meant that he was fourteen MAG machine guns short. 9th Engineer Company laid minefields covering Salinas Beach, the north end of the airfield, on both sides of the inlet north of the Schoolhouse and between Middle Hill and Coronation Ridge. The Regimental Chaplain, Father Mora, later wrote: The conscripts of 25th Infantry wanted to fight and cover themselves in glory. The conscripts of 12th Infantry Regiment fought because they were told to do so. This did not make them any less brave. On the whole they remained admirably calm.’

As we have seen, Brigadier Thompson had been under significant political pressure to demonstrate British resolve. On 24 May, after he had issued formal instructions to 2 Para to raid the Darwin Peninsula, Lieutenant Colonel Jones and his Intelligence Officer, Captain Alan Coulson, flew to Brigade HQ where they were given the latest intelligence. A member of the Brigade Intelligence Section:

I was already aware that the SAS had made an assessment of the enemy strength at Goose Green, but if 2 Para chose to believe the SAS, the deeper they penetrated toward Goose Green, the more unknown they would face. The intelligence gained from the interrogation of the Argentine sergeant was the most recent available.

Over the next two days, Jones reviewed his options. Brigadier Thompson initially told him that helicopters were required for the SAS seizure of Mount Kent. A night amphibious landing on Salinas Beach was rejected because of navigational difficulties and warships were needed to defend San Carlos Water. Marching the 15 miles to Goose Green was the only option. 2 Para also faced another difficulty – no patrolling: ‘The activities of the SAS were particularly frustrating. SAS operations both before Darwin/Goose Green and Wireless Ridge inhibited the Battalion’s own patrolling activities and yet no proper debriefing of the SAS patrols was ever made available to the Battalion.’ (2 Para post-operational report)

When Jones sent C Company to recce a route to Darwin, near Canterra House, it reported an Argentine company and a troop carrier. 12 Platoon (Lieutenant Jim Barry, Royal Signals) was lifted by helicopter to investigate, however it took four hours to navigate across trackless moorland before finding the house to be empty. Jones then briefed his company commanders that the Battalion would raid Goose Green early on the 26th and would have three 105mm Light Guns from 8 (Alma) Commando Battery in support. At last light, D Company (Major Phil Neame), tasked to secure the start line, descended Sussex Mountain, collected 12 Platoon and set off for Camilla Creek House. Meanwhile, D Squadron recce patrols had been inserted on Mount Kent and Thompson was concentrating on reinforcing them with 42 Commando and a 105mm Light Gun battery by Chinook helicopters expected from the Atlantic Conveyor. However, when news of the sinking of the ship arrived, believing that attacking Stanley was more militarily important than a political demonstration, Thompson scrubbed moving the three guns to Camilla Creek House. Unaware of the difficulties faced by Thompson, Jones was livid: ‘I’ve waited twenty years for this, and now some fucking marine’s cancelled it.’ 12 Platoon returned to Canterra House and D Company snaked back to Camilla Creek House. Jones then arranged for helicopters at 6.00 am next day to lift D Company to Camilla Creek House but was first told that only one aircraft was available, and then none – bad weather again. This did little to soothe his impatience. 12 Platoon arrived back at 2 Para, cold, hungry and tired.

Although Goose Green was not a threat, on 26 May Thompson was summoned to speak to Admiral Fieldhouse: ‘As clear and unequivocal were the orders from Northwood. The Goose Green operation was to be remounted and more action required all round. Plainly the people at the backend were getting restless. (Thompson, No Picnic)

The instructions contravened Major General Moore’s 12 May directive, nevertheless when Lieutenant Colonel Jones was told by Thompson that the raid was back on, he was delighted, as was 2 Para. C Company occupied Camilla Creek House followed by the rest of the Battalion. Initially, the pace was an unrealistic Aldershot ‘tab’ and it was only after a soldier in A Company collapsed that the stop-go, stop-go march changed into a practical pace. Thompson refused to allocate the Blues and Royals to the attack because he did not believe that light armour could negotiate soft ground.

During the day, Brigadier General Menendez instructed Brigadier General Parada to command 3 Infantry Brigade operations from Goose Green; however the duty flight commander refused to accept Menendez’s orders, as they had not been ratified by Air Force headquarters. Naval and air force headquarters often refused to implement his orders until they had been ratified by their own staff. Parada then instructed Piaggi:

Task Force Mercedes will reorganize its defensive positions and will execute harassing fire against the most advanced enemy effectives, starting from this moment, in the assigned zone, to deny access to the isthmus of Darwin and contribute its fire to the development of the principal operation. The operation will consist of preparing positions around Darwin for an echelon defending the first line, and occupying them and from there putting forward advanced combat and scouting forces, as security detachment, supporting the principal operations with harassing fire against Bodie Peak-Canterra Mount-Mount Usborne.

Although A Company was in defensive position on the high ground of Darwin Ridge behind the minefields, Piaggi instructed First Lieutenant Manresa to move his Company into unprepared positions on Coronation Ridge north of the minefields. Manresa was concerned that his half-trained conscripts were leaving the security of their positions, which were taken over by Second Lieutenant Peluffo’s platoon. During the night, Chanampa’s guns registered on to targets, most astride 2 Para’s route, which brought some discomfort to the paras. Shortly before dawn on 27 May, 2 Para were crammed into the house and ten outbuildings that made up Camilla Creek House. When the Signals Platoon tuned into the 10.00 am BBC World Service news and heard ‘A parachute battalion is poised and ready to assault Darwin and Goose Green’, there was stunned silence at the enormity of this breach of security. No one has ever owned up to the leak but political expediency from within Thatcher’s War Cabinet is suspected. A furious ‘H’ Jones ordered his Battalion to disperse, which made co-ordination difficult. The Argentines believed the announcement to be a hoax because they believed that no one in their right mind would broadcast an attack.

Two Recce Platoon (Lieutenant Colin Connor) patrols clashed with Lieutenant Morales’s Recce Platoon. At about 12.30 am, three Harriers arrived to support Lieutenant Connor, however, Captain Braghini’s gunners shot down Squadron Leader Iveson. Bailing out over Paragon House, he was rescued three days later by a 3 Commando Brigade Air Squadron Gazelle. When Morales was ordered by Piaggi to investigate activity north of Camilla Creek House, Morales and three soldiers driving along the track to San Carlos in a commandeered blue Land Rover were captured and,, under interrogation, they admitted the Argentine garrison was alert to an attack. Unfortunately, they were not sent to Brigade HQ for more expert interrogation.

Jones called an Orders Group for 11.00 am, however with the Battalion spread out it was not until 3.00 pm, with the light fading fast, that his officers assembled. Lieutenant Coulson was midway through the crucial intelligence briefing when Jones’s impatience prevailed and he interrupted him, consequently denying the Battalion all the intelligence available to them. Jones planned that the raid had developed into an all-out ‘six-phase night/day silent/noisy battalion attack’:

Support Company to establish a firebase at the western end of Camilla Creek.

C Company to secure the Start Line at the junction of Camilla Creek and Ceritos Arroyo and then become Battalion reserve.

A Company to attack the right flank of 12th Infantry Regiment toward Darwin Hill.

B Company to attack the left flank around the derelict foundations of Boca House.

A Company to attack Coronation Point.

D Company to deal with a platoon position on high ground 1,000 metres north of Boca House.

B Company to attack Boca House.

A Company to exploit to Darwin.

C Company to push through B and D Companies to clear the airfield.

A Company to take Darwin.

B Company to attack 25th Infantry Regiment platoon at the Schoolhouse.

C Company to move into a blocking position south of Goose Green,

D Company to liberate Goose Green.

The fourteen hours of darkness would be used to cover the 6,500 yards to Goose Green, with nine hours for battle preparation and the move to the Start Line, leaving five hours to advance against an enemy in depth over unknown ground. Jones concluded his orders: ‘All previous evidence suggests that if the enemy is hit hard, he will crumble.’ So far, there was no suggestion that they would. Time was short and some company, platoon and section orders lacked some detail. After two sleepless nights and an exhausting approach, the paras were tired.

During the late afternoon, 5th Fighter Group launched the first mission against British positions when two Skyhawks attacked the 40 Commando positions at San Carlos, killing Sapper Pradeep Ghandi, of 59 Independent Commando Squadron RE. One pilot forced to eject from his Skyhawk was returned to Argentine forces by local islanders. Two other Skyhawks attacked Ajax Bay with parachute-retarded bombs and six Royal Marines were killed. Thompson:

Three 400kg hit the Field Dressing Station itself without exploding, one passing through the roof and bouncing on the ground outside. The two others remained in the Dressing Station until after the end of the war. The bombs that did explode in the BMA started fires among the piles of ammunition stacked close by, mainly 81mm mortar ammunition and Milan. These exploded all night a hundred metres or so from the Dressing Station and Logistic Regiment Headquarters, sending shrapnel whining through the darkness and destroying all of 45 Commando’s Milan firing posts. The netted loads of gun and mortar ammunition waiting to be lifted forward to 2 Para were also destroyed. These had to be replaced quickly before 2 Para’s battle (at Goose Green) started. (Thompson, No Picnic)

At 10.00 pm, C Company and Recce Troop, 59 Independent Commando Squadron RE cleared the route to the start line, which included the unlucky sappers wading waist deep in freezing water checking three bridges for obstacles. Phase One was complete except that Recce Platoon had secured a fence about 400m north of the correct start line. In Grantham Sound, HMS Arrow opened fire, in support of A Company’s attack on a suspected Argentine position at Burntside House. Bullets smacked into the buildings, showering Mr and Mrs Morrison, his mother, a friend and a dog with wood, glass and debris. A Company skirmished to a fence 350m beyond the building, however the Argentine patrol had retired. Phase Two was complete, but for many paras experiencing battle for the first time, the reorganization was chaotic. A 2 Platoon section commander: ‘Nobody knew where we were. The rest of the Platoon didn’t know where my section was, and I didn’t know where the platoons were. One of the platoons, if I remember correctly, crossed over one another. I wasn’t quite sure who was in front of them, but knew it wasn’t the enemy.’

B Company was delayed in crossing their start line until 11.11 pm, much to Lieutenant Colonel Jones’s frustration, by A Company’s difficulties. Crosland:

I was walking around my leading platoons and the atmosphere was very like the tension before a parachute descent – but underlying this, quiet confidence. At 3am, the word was given and the Company rose as one to start our long assault. My orders were clear – advance straight down the west side, destroying all in the way. We contained a lot of firepower. This was going to be a violent gutter fight, trench by trench – he who hit hardest won. (Adkin, Goose Green)

Supported by HMS Arrow, bayonets fixed, B Company quickly overran Manresa’s conscripts. The advance of 6 Platoon (Second Lieutenant Clive Chapman) on the left was initiated by reports of a ‘scarecrow’, which then moved and said ‘Por favor’. Chapman:

There was a lot of light in the air at the time from our Schermulys and from our 2-inch mortars. I remember thinking at the time that the field-craft of the troops as they attacked was fantastic. They were weaving left and right, covering in bounds of moving men and really getting stuck into the fight. There was little need to hit the ground and people generally knelt between moves. It was a very dark night, and we had crossed to about 20 to 40 metres from the Argentines when the fight began. Just about every trench encountered was grenaded. Kirkwood [Private Ian, Chapman’s radio operator] and myself even took out a trench. There was continuous momentum throughout the attack and it was very swiftly executed. The success of the attack had an electrifying impact on the platoon. (Adkin, Goose Green)

At about 4.30 am, Manresa’s A Company broke contact and reorganized with 7th Platoon (Lieutenant Horacio Munoz-Cabrera) on Coronation Ridge. B Company advanced through the Argentine positions on Burntside Hill, briefly reorganized and then ejected the Argentines from Coronation Ridge. Private Curtis:

I was breathing hard, exhaling to calm my nerves and gritting my teeth. With eyeballs on stalks, I scanned left, right and in front of me. Increasingly the ground began to slope up on the right. This had the effect of channelling 4, 5 and 6 Platoons slightly towards the flatter ground. To my front and left, a blaze of firepower exploded out of the darkness. 6 Platoon had come under attack. We all went to ground initially and then 4 Platoon opened up on all fronts. As ordered, 5 Platoon held, ready to support or go to either flank. Squashed flat against the frozen ground, I could feel my heart pounding despite the incredible noise. Then during a lull in the gunfire, I heard voices to my right. Although muffled, I could have sworn they were Spanish. We were using classic infantry tactics – just like we’d practised over and over again on Salisbury Plain and at Sennybridge. But everything you do on exercises, even in the darkness, is all neat and précis; when it comes to doing it for real, it’s incredibly confusing. The text drill of dash – down – crawl – sights – observe. And fire control goes out of the window. As you start taking real live ammunition and rounds are zipping about your helmet as you crawl along, you can find yourself firing with your head down, not always looking where the rounds are going. I knew it was bad practice but it was very hard to avoid. (Curtis, CQB)

The Argentines were shaken by the controlled ferocity of B Company. Several were killed, and a few, still huddled in sleeping bags in their trenches, were captured. Chapman later credited that the success of the attack was profound faith in Major ‘Black Hat’ Crosland, so nicknamed because of his habitual black woollen hat.

At 2.00 am, HMS Arrow’s main armament jammed and remained inactive for the next two hours. Captain Bob Ash RA was the B Company Forward Observation Officer and had just repaired a malfunctioning radio:

It was totally black, and you couldn’t even make out the horizon. I started using the ship for adjustment with their star shell. After a few rounds it jammed – and that was the end of it … So, I didn’t even get one ‘in the parish’ where I could try and pick up any positions.

2 Para were now reliant upon 8 (Alma) Commando Battery, and three Mortar Platoon 81mm mortars and the limited amount of ammunition they had. On the right, D Company, in reserve, advanced. Major Neame:

Unfortunately, we had somehow got ahead of ‘H’. He suddenly came stomping down the track from behind. ‘What the hell are you doing here?’ were his opening words. My response of ‘Waiting for the battle to start’ did not placate him; he didn’t take kindly to his reserve company being closer to the battle than he was. (Adkin, Goose Green)

Lieutenant Colonel Jones disappeared and when he came under fire from Coronation Hill, he instructed Neame to deal with the enemy. Neame, like most of 2 Para that morning, had no idea where they were in relation to the enemy or their own forces, nevertheless D Company advanced and clashed with Manresa’s men on Coronation Hill. Lieutenant Chris Webster commanded 11 Platoon on the left flank:

Corporal Staddon’s Section and Platoon Headquarters were best placed to move close toward the enemy, so we crawled up in more or less a straight line. Suddenly a heavy calibre opened up and I think that was when Lance Corporal Cork was hit in the stomach. Private Fletcher went to assist and at about the same time some mortars started falling around us. Luckily the ground was soft and absorbed most of the blast, but I remember thinking that command and control is all very well but what can you do when you and everyone around you is deaf. (Adkin, Goose Green)

Cork and Fletcher were the Battalion’s first fatalities. When 10 Platoon, on the right, attacked trenches on his right flank and a few rounds impacted near B Company, Neame resolved the matter with Crosland. The fighting was tough and D Company lost three dead and two wounded. One problem quickly emerged – the casualty evacuation plan was weak and some soldiers would wait twelve hours waiting to be collected. Once again, 2 Para was delayed as D Company reorganized. Phase Three was complete.

A Company had been waiting in heavy drizzle west of Burntside House and when Jones ordered the Company to advance in Phase Four it was about 4.30 am, half an hour behind schedule. HMS Arrow was still non-operational and Major Rice was switching the Light Guns between the companies. Support Company, apart from the Medium Machine Gun Platoon, was directed by Jones to find a fire support base. By the time that A Company reached Coronation Point the timetable had slipped by about an hour and twenty minutes. Major Farrar-Hockley, with A Company well ahead of B and D Companies, wanted to press on and take advantage of the darkness. Adkin: ‘When Farrar-Hockley went forward to verify his position, he was aware that if he ignored his Phase 4 orders to remain in reserve (to B Company attacking Boca House) and advanced on Darwin Hill he could catch up on lost time. He radioed Tac HQ for authority to continue the advance.’ (Adkin, Goose Green)

However, Lieutenant Colonel Jones, whose command style was restrictive, told him to wait so that he could personally assess the situation. Jones had difficulty finding A Company in the dark and when he eventually instructed it to seize Darwin Hill, Farrar-Hockley moved 3 Platoon (Second Lieutenant Guy Wallis) to a fire support position north-east of Darwin Pond near the bridge. A Company then advanced with 2 Platoon (Second Lieutenant Mark Coe) leading, taking as his axis a gorse-filled gully leading onto Darwin Ridge. Ahead was a thin fence. Time was short, dawn was peeping over the horizon and it was still drizzling.

Lieutenant Colonel Piaggi was confident that if his main defence line across the isthmus held, he stood a good chance of victory. Pushing 7th Platoon, 8th Infantry Regiment (Lieutenant Second Guillermo Aliaga) on to Boca Hill, he instructed 1st Platoon, C Company, 25th Infantry Regiment (Second Lieutenant Nestor Estevez) to reinforce the composite Headquarters Company platoon (Second Lieutenant Peluffo) on Darwin Ridge and told both officers that defence was more important than attack. The survivors of Manresa’s shattered company trickled back and were slotted into defensive positions. About 200 defenders occupied at least twenty-five trenches, bunkers and shell scrapes. A brief break in the weather gave Air Commodore Pedrozo the opportunity to evacuate several Bell-212 helicopters from Goose Green. The CH-47s had left three days before.

In the grey gloom of a wet dawn, Estevez’s men thought that figures approaching the ridge were more A Company survivors. Corporal Camp’s section reached the gorse when three figures appeared on the spur to the right. One para thought it was a civilian walking a dog, but Lance Corporal Spencer believed them to be paras and shouted. The three figures waved amicably and one shouted back in Spanish. There was a momentary pause before Camp’s section opened fire and dived for cover in the gorse. The defenders of Darwin Ridge then opened fire at A Company strung out in file in the open below them.

While 2 Section (Corporal Dave Hardman) and Platoon Headquarters joined Camp, Corporal Steve Adams’s section skirmished to the right of the spur but was forced to withdraw under heavy fire which wounded Adams and Private Tuffen. The latter could not be rescued but Adams was able to join Camp. Company Tac HQ made it to the gorse, as did most of 1 Platoon (Sergeant Terence Barratt). As those caught in the open withdrew under accurate fire onto the small beach of Darwin Pond, the Company medic, Lance Corporal Shorrock, was shot in the spine. Private Martin was a member of Corporal David Abols’s Section in 1 Platoon:

I was at the back of the Platoon with Company Headquarters. When the firing started, we doubled forward a bit, went to ground and opened fire on the hill. We were soon under mortar fire as well but saved by the soft ground. One man was killed going forward. It was all chaos with no orders as the Section Commander had gone into the gully. Gradually we made our way down the beach. Shorrock crawled back and we put a dressing on him. We met a signaller who told us that 2 Platoon had been wiped out. (Adkin, Goose Green)

The soldier killed was Corporal Michael Melia, of 59 Independent Commando Squadron RE. At about the same time, when 7th Platoon, 8th Infantry Regiment, on Boca Hill opened fire on B Company advancing down Middle Hill, 4 and 6 Platoons found cover in the gorse; 5 Platoon, however, was caught in the open by artillery and struggled back up the bare slopes. Private Jimmy Street opened up with his 2-inch mortar and then Private Curtis heard him shout to Private ‘Taff’ Hall that he had been hit in the legs. Hall then screamed, ‘My back, my back!’ As Curtis reached Street, Privates Steve Illingworth and ‘Pooley’ Poole were with Hall when a shell burst nearby, bowling Curtis over. Dazed, he got to his feet and sheltered in the smoking crater. After Illingworth and Poole had dragged Hall into shelter, Illingworth then ran back to where Hall had been wounded, stripped off his webbing and was sprinting back, shouting ‘We need the ammo!’ covered by Curtis with his GPMG, when he was killed 15-feet from the crater.

Farrar-Hockley’s immediate problem, several trenches on the eastern slopes of the spur, were attacked by ad hoc groups of officers and soldiers from the Royal Artillery, Royal Engineers and Parachute Regiment working together to nibble at the defences. Corporal Camp and Private Day, who was Second Lieutenant Coe’s radio operator, used Private Robert Pain’s back as a GPMG firing platform. A left-flanking attack up the gully by Coe and 2 Section stalled at the cost of Private Worrall seriously wounded on the wrong side of a bank alight with burning gorse. Corporal Abols was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his conduct during the battle:

I returned to Corporal Prior and Worrall but we couldn’t coordinate the covering fire because of the noise of the battle, so I skirmished forward and dived over the bank again to discover that Corporal Russell had been hit by shrapnel from an anti-tank weapon. Then Sergeant Hasting, Lieutenant Coe and a few privates assisted us with covering fire, so I returned to Corporal Prior and we decided to throw a smoke grenade, which would be the signal for the covering fire … I threw the smoke grenade, then we grabbed Worrall but couldn’t move him as his webbing had caught on some gorse roots. By the time he was ready to be moved, the smoke had disappeared, so we decided to take a chance and go over the bank with him. Just as we were about to move, a sniper shot Corporal Prior in the back of the head… Then Corporal Hardman and Lance Corporal Gilbert came over and we managed to get Corporal Prior over the bank and returned for Worrall… I then rested and had a few fags and returned to the battle on the hill. (Adkin, Goose Green)

Corporal Underwood, the Company Mortar Fire Controller (MFC), was directing fire but the Mortar Platoon was running short of ammunition. Deciding that concentrated fire was essential, Farrar-Hockley grouped six GPMGs under Sergeant Barratt on the spur as a fire base to dominate Darwin Ridge, but it had only enough ammunition for about an hour. North of Darwin Pond, 3 Platoon gave support at extreme range and was then shelled. Fog at sea prevented a Harrier strike.

The battle was at a critical stage. The Argentine platoon commanders had inspired their conscripts and at 6.00 am, when Piaggi informed Menendez that the British had been halted, optimism prevailed in Stanley. In anticipation of Skyhawk support, Company Sergeant Major Coelho laid out strips of white sheets as markers. Before 2 Para had attacked, the three Argentine Pack Howitzers were well forward, however as the Argentines withdrew, the parachute gunners changed position several times, although always into unprepared sites. Nevertheless throughout the battle, they kept up the pressure. The one jeep that First Lieutenant Chanampa had was invaluable for towing and moving ammunition. When Estevez was killed on Darwin Ridge, while adjusting artillery fire, his radio operator, Private Fabrizio Carrascul, continued directing the guns until he too was killed. Thereafter Chanampa’s targets tended to be either speculative, based on local knowledge or from the map. Estevez was posthumously awarded Argentina’s highest gallantry award.

At Camilla Creek House, the demand on 8 (Alma) Commando Battery was high; the guns became unstable and were being resighted about every fifteen minutes. The lack of meteorological information, the inability of Forward Observation Officers to see fall of shot and a gusting wind was making accurate shelling difficult. One gun developed a buffer oil leak, which was cured with rifle-cleaning oil. Empty shell cases littering the gun pits were removed by the gunners, contributing to their fatigue – most had not rested for thirty-six hours. In spite of the weather, three Pucaras appeared over Camilla Creek House at about 8.00 am, and as Lieutenants Cimbra and Arganaraz lined up for a low-level rocket attack on the gun line, a Blowpipe fired by 43 Battery, 32nd Guided Weapons Regiment Blowpipe detachment, commanded by Battery Sergeant Major Wilson, deflected Cimbra. Another missile launched at Arganaraz exploded on the ground, flinging the Pucara upside down for a short time. All three aircraft returned to Stanley.

Although A Company had been halted in front of the strongest part of the defence of Darwin Ridge and although he had reserves, Lieutenant Colonel Jones rejected several suggestions. Neame, well placed in the centre to support both flanks, suggested to Farrar-Hockley on the Battalion radio net that D Company could outflank the Argentine defences, but was told by Jones, ‘Stop clogging the air; I am trying to conduct a battle.’ Major Crosland suggested that B Company could seize Boca Hill and roll up the enemy from the west. Captain John Young suggested placing Milan Platoon on Middle Hill to shoot at the main defence line. Lieutenant Peter Kennedy, C Company’s Second-in-Command, assembled twelve GPMGs on the eastern slopes of Coronation Ridge and when he asked A Company for targets was told, ‘Get off the radio. I’m trying to run a battle.’

Trapped at Darwin Pond for an hour and unable to influence the fighting, Lieutenant Colonel Jones was impatient. His radio operator, Sergeant Norman: ‘The CO got on the radio and told them to get a grip, speed up and continue the movement, which they couldn’t. So he said “I’m not having anymore of this” and decided to go and join up with A Company. To say he got a little pear-shaped would be an understatement.’ (Adkin, Goose Green)

Crawling, running, sprinting and diving, the radio operators that make up Tactical HQ, weighed down with radios, batteries and bergens, found it difficult to emulate the fast pace set by Jones. It was about 8.30 am. According to Wilsey: ‘H effectively ended up running the battle in the gully.’ (Wilsey, H Jones VC)

Jones urged Major Rice and Captain Worsley-Tonks to get the guns and mortars going respectively, however the British and Argentines were too close. When Jones instructed Farrar-Hockley that he should seize a ledge at the top of the spur, Farrar-Hockley assembled about fifteen men. Wolsey-Tonks arranged for smoke but the wind dissipated this quickly. Lance Corporal Gilbert:

I can’t remember anybody organising anything; we just went. We were walking initially, then crawling to the top. As we went forward round the slope, I was in time to see Captain Dent killed. He was hit in the chest, fell back on his radio and was then hit again. I crawled past the Adjutant, who was on his hands and knees, encouraging us saying ‘That’s it, lads, Airborne all the way. Remember Arnhem!’ After ten minutes I looked back and he was dead too. Myself and Corporal Hardman worked our way to the left while the position was being smoked. Then it dispersed and I saw Hardman fall. He didn’t move. I crawled over to him and checked. He was obviously dead. I had to take up a fire position behind him, using his body as a rest. I felt his body twitch as it was hit again. I took his ammo and crawled back. (Adkin, Goose Green)

Further attacks would have been suicidal and the survivors found cover. Sergeant Blackburn then heard Jones mutter, ‘We’ve got to do something about this.’ Wilsey:

He took command of the situation locally and with the resources immediately available deliberately set out to regenerate the lost momentum. He sensed how to rejuvenate the assault on the ridge. His whole life had been in preparation for this moment. He did not tumble into it; it was coolly calculated. He deliberately led an out flanking movement to set an example, to show the way, to tip the balance at a critical moment and to determine the outcome. This, in the final analysis, is the commander’s job. (Wilsey, H Jones VC).

Without telling anyone or looking back, he ran up the gully that Corporal Adams had attacked when A Company was first fired upon, past the seriously wounded Private Tuffen. Sergeant Barry Norman, his close escort, was the first to move, followed by Lance Corporal Beresford, who was part of his escort and had been Jones’s driver, Major Rice and his two signallers. Jones advanced up a small re-entrant toward a trench, which Corporal Osvaldo Olmos, from Estevez’s platoon, later claimed was held by his group. Norman shouted, ‘Watch out! There’s a trench to the left!’ and dived for cover. Jones evidently heard the warning and briefly paused to change his Sterling SMG magazine. Norman, while under heavy fire from the left, then fired a complete SLR magazine into the trench and also changed magazines, although this took longer than he expected because the magazines had become jammed in his pouch. When he popped up, seeing Jones check his magazine and advance up the slope, he shouted for him to watch his back. However, Jones continued and then fell. It was 6.30 am. Major Chris Keeble was at Battalion HQ to the north of Darwin Pond. ‘And in this confusion over the radio came “Sunray is down”. I couldn’t believe it and actually asked for verification. Colour Sergeant Blackburn, his signaller shouted again, “Sunray is down for Christ’s sake”. Then a surge of apprehension and fear ran through me.’ (Adkin, Goose Green)

Then, at 6.31 am, when Brigade Headquarters heard the message ‘Sunray injured. Sunray Minor taking over. Over’, there was also disbelief. Brigadier Thompson, assured by Keeble that he could win the battle and with the Mount Kent operation postponed, ordered ammunition to be flown to 2 Para. Soon afterwards, the Argentine defence began to wither, largely because the Argentines were short of ammunition and with little prospect of resupply. Company Sergeant Major Colin Price fired a 66mm at a bunker but missed, however Corporal Abols was successful and the paras seeped on to Darwin Ridge. Second Lieutenant Peluffo was lying in a trench after being wounded in the head and leg:

I told a soldier to tie a napkin to his rifle and wave it. He was shot at. He got back into the trench very frightened. I told him to wave it again, so he came out of the position and then we saw the British coming out into the open. I was still at the bottom of the trench. I couldn’t move … A British soldier arrived and asked me in English if I was all right. I didn’t understand him. I saw him standing there with a sub machine gun and thought to myself: Well, this is it. Then he asked me again ‘Are you OK?’ and I realised that he was not going to shoot me after all. He told me the war was over for me and that I would be going home. (Bilton and Kominsky, Speaking Out)

By about 9.30 am, the fight for Darwin Hill was over at the cost of three officers and three other ranks killed and eleven wounded. Of the ninety-two defenders, eighteen were killed and thirty-nine wounded. Collecting 3 Platoon, C Company moved through A Company.

For fifteen minutes, Sergeant Norman waited. When the firing died down, he reached Jones and, turning him on his back, assessed that from the lack of blood, he had internal wounds and not long to live. Other paras placed Jones on a corrugated sheet to take him to a helicopter landing site but he rolled off. A second attempt succeeded. A post mortem suggested that he had been mortally wounded by a single bullet entering his shoulder and exiting midriff. Controversy will surround Lieutenant Colonel Jones and whether his action unlocked the defences. His bodyguard, Sergeant Blackburn summarized: ‘It was a death before dishonour; but it wouldn’t have passed junior Brecon.’ Infantry training took place at the training area at Brecon.

Following frequent requests by Major Farrar-Hockley to evacuate his wounded, at about 10.30 am, two 3 Commando Brigade Air Squadron Scouts, which had been flying ammo forward and returning to Ajax Bay with casualties collected from the RAP, were briefed at Camilla Creek House to collect A Company wounded. Captain Jeff Nisbett RM led the flight. Meanwhile, in response to two aircraft detected leaving Stanley to support Task Force Mercedes, at 10.58 am, an air raid warning ‘Red’ was passed to 2 Para. Shortly before midday, Lieutenant Miguel Gimenez, on his second mission of the day, singled out the Scout piloted by Lieutenant Richard Nunn RM. Sergeant Belcher was his crewman:

Suddenly two Pucaras appeared, approaching head on. They split up, so did we. Nunn turned about and we were hit by a burst of cannon fire from directly behind. I was hit in the right leg above the ankle, which took me out. I lay across the back and started to pull out the aircraft’s first aid kit … while at the same time trying to watch the Pucara and tell Nunn where it was, what it was doing, when it fired, talk him through the situation so he could take evasive action. It flew past our starboard side, turned on its wing and came at us head on, firing its 7.62mm machine gun. Nunn was struck in the face, dying instantly, and I was hit again, this time above my left ankle. We crashed, bounced, turned through 180 degrees, the doors burst open and I was flung clear. (Adkin, Goose Green)

Returning to Stanley, the two Pucaras separated in the mist and Gimenez vanished. His wrecked aircraft was found in 1986. Nunn’s brother, Chris, had commanded M Company, 42 Commando in the recapture of South Georgia. There was still a battle to be fought. After hearing that Jones had been killed, Major Keeble spent twenty minutes trying to get a clear picture of what was actually happening 800 yards to the south. He had D Company in reserve and the question was whether to reinforce A Company or sort out B Company who were pinned down by machine-gun fire from the Argentine defensive position at Boca House.

Assessing that the best opportunity lay with B Company, Keeble, whose style of command allowed for initiative, passed command to Major Crosland and then led his Tac HQ, laden with extra ammunition, toward the fighting, scrambling for cover as the two Pucaras roared overhead. In the meantime, Keeble: ‘In the time it took for me to get up to B Company, Phil Neame – the canny Phil Neame – had realized that he could outflank Boca House by slipping his Company down onto the beach; there was a small wall between the grassland and the beach.

Sending 10 Platoon to join Support Company on Middle Hill firebase, Neame led 11 and 12 Platoons along the wall. Though under fire from Milans, the Argentines mortared the firebase until two Milans struck Second Lieutenant Aliaga’s position and then, at about 11.10 am, white flags appeared. 12 Platoon, dangerously exposed, advanced across open ground against the enemy position showing white flags, but ran into a minefield. When the Middle Hill firebase then opened fire, Neame radioed for everyone to stop firing until 12 Platoon reached Boca Hill where they found twelve dead Argentines and fifteen wounded, including Aliaga, most terribly injured by the Milans.

At about the same time, at Stanley Racecourse, First Lieutenant Esteban with a combat team of 3rd Platoon, A Company, 25th Infantry Regiment, and survivors of Combat Team Eagle, were squeezed into an Army Puma and six Iroquois, and were escorted by two Hirundo gunships to a landing site several hundred yards south of Goose Green. Although Piaggi’s most experienced officer, Esteban handed over 3 Platoon to Second Lieutenant Vasquez and was instructed to organize the defence of Goose Green with Air Force personnel. Esteban took no further part in the fighting. All that now stood between the British and Goose Green was Vasquez’s platoon at the Schoolhouse and 3rd Platoon, C Company, 25th Infantry Regiment (Second Lieutenant Gomez Centurion) holding the high ground around the airstrip windsock, and plugging the gap with the School of Military Aviation security companies. Brigadier General Parada was still encouraging Piaggi to counterattack.

Meanwhile on the left, C Company and 3 Platoon had pushed through A Company, who had set up a firebase on Darwin Hill, however as they descended, Air Force Rh-202 gunners and Army mortar and machine-gun crews opened fire, killing one man and wounding eleven, including Major Hugh Jenner, the Company Commander. Support Company suppressed the Argentine fire, but the range was long. It was about 2.30 pm. On the right, B Company had halted. Private Curtis:

Crosland called B Company together and said we were going to attack Goose Green from the south-west. It meant that we’d be effectively isolated from the rest of the Battalion, but it was a chance he was willing to take. We started tabbing off the hill in arrowhead formation. Again, it was like the First World War stuff, as howitzer rounds whistled and landed randomly around us. But the fear of the night had gone and I was far happier fighting in the day, knowing everyone’s position. I also felt more secure to be moving forward as a company again. It was also re-assuring to see JC [John Crosland] wearing his black bobble hat, looking around nonchalantly. He had an aura of invincibility about him. (Curtis, CQB)

In the centre, D Company was approaching the airstrip. With 10 Platoon weakened by injuries and therefore detached, shortly after examining a suspected command bunker on the edge of the airfield, and assembling some prisoners, they came under fire from Darwin Hill. Waving their red berets, the paras managed to get the fire lifted. Neame had hoped to bypass the Schoolhouse, which was a known strongpoint, but it threatened his left flank. D Company was widely dispersed: 10 Platoon were at the airfield; 12 Platoon had run into more mines and, after their experience at Boca Hill, were nervous. He was about to order 11 Platoon to attack when he learnt that Lieutenant Barry and two soldiers had been killed arranging a surrender near the windsock – the ‘white flag’ incident.

12 Platoon had been advancing towards Goose Green when a white cloth was seen being waved near the windsock. Believing the Argentines from Centurion’s Platoon wanted to surrender, Lieutenant Barry told Sergeant Meredith, his Platoon Sergeant, that he was going forward. When this was reported to Company HQ, Major Neame instructed him to wait, however Barry had set off. With his medic/runner, Private Godfrey, and his radio operator, Private ‘Geordie’ Knight, Barry collected Corporal Paul Sullivan’s section; Sullivan uttered prophetically ‘He’s going to get me killed.’ Godfrey:

There was a group of three or four Argies with a white cloth wanting to surrender. I’ve no doubt about this group. They were less than 100 metres from us, but the ground was open like a football field. They were up this slope by a fence with a gap in it. Mr Barry and his radio operator, Geordie Knight, were in the lead with myself a short distance behind, then came Corporal Sullivan’s section in support. When we got to the top, I saw that there more Argies in trenches nearby. The first group still seemed to want to give up, but I was worried about the others as they were not leaving their trenches. Mr Barry went right up to the fence, only a few feet from the Argies. I was about 200 feet behind him. He started to demonstrate to the Argies that they were to surrender by putting down their weapons. He went through the motions of putting down his own. (Adkins, Goose Green)

Godfrey recalled that a long burst of automatic fire cracked overhead from behind, most likely from a Machine Gun Platoon gunner seeing Argentines in the open. There was a furious exchange of fire. Godfrey:

Suddenly there were bullets everywhere. All the Argies opened up. Mr Barry was hit at point blank. I fell flat. There was fire from everywhere. I could see rounds striking the ground all round; a lot was coming from the trenches. I was in a bit of a state as the strap of my medical bag was wrapped around my neck. A bullet went through my sling and another through the heel of my boot. (Adkins, Goose Green)

Godfrey dived into a tractor tyre rut. Knight shot two skirmishing Argentines and Carter dominated another trench with rifle fire. When Corporal Kinchin advanced with his section, Corporal Jeremy Smith was killed instantly when a bullet struck his 66mm as he squeezed its trigger. Corporal Sullivan was also killed and Private Sherrill badly wounded. When Knight reported that Barry was down, Meredith opened fire on the Argentine trenches with a GPMG with deadly accuracy, not so much because his Platoon Commander was down, but because his frustration at ‘Barry for being so stupid’. The news-papers inevitably made much of this scrap, however both sides agreed that this was a tragic misunderstanding. The Argentines later claimed that when Second Lieutenant Centurion was offered terms by Barry, he replied, ‘Son of a bitch! You have got two minutes to return to your lines before I open fire. Get out!’

At the same time, Vasquez’s platoon was vigorously defending the Schoolhouse. 11 Platoon had opened the attack by firing four 66mm at an outhouse and then Second Lieutenant Waddington was leading a small group along the southern foreshore of the inlet when he met the Patrol Platoon Commander, Captain Paul Farrar, crossing the bridge. Thereafter C and D Companies intermingled. Vasquez eventually abandoned the building when it was set on fire and withdrew covered by Braghini’s two 35mm Oerlikons, preventing British exploitation. With Goose Green surrounded, Major Keeble ordered 2 Para to go firm. It was about 2.30 pm.

After three Pucaras had flown from Argentina during the afternoon, two of them and two Navy MB-339 Aermacchis were prepared for a sortie against British mortar positions at Goose Green. Shortly after 4.00 pm, when the Aermacchis attacked D Company, Marine Strange, of 3 Commando Brigade Air Defence Troop, shot down Sub Lieutenant Daniel Miguel, who died as his aircraft crashed near B Company. The Pucaras approached from the north-west and attacked D Company with napalm, however, the paras were alert and Lieutenant Cruzado ran into massive ground fire which smashed his controls. Bailing out at low level, he was captured. Three Harriers then damaged the Oerlikons with 2-inch rockets. The gunners abandoned them, leaving the Argentines without artillery and air defence.

By late afternoon, the Argentine situation at Goose Green was serious and Brigadier General Menendez released Combat Team Solari from the Reserve to reinforce Task Force Mercedes. When a flight of Army UH-1H Iroquois arrived on Mount Kent to collect them, First Lieutenant Ignacio Gorriti, the B Company Commander, received a message from Brigadier General Parada cancelling the move but it was too late. Shortly before dusk at 6.30pm, the helicopters landed south of Goose Green. To Major Crosland, they posed a threat. Private Curtis:

It was getting dark as Crosland called his herd together. Bedraggled bodies emerged from enemy trenches and sangars that we now occupied; we had been in battle for the best part of thirty-six hours, with hardly any food, drink or sleep. The OC decided to take us to a knoll just behind our position – the highest feature around Goose Green – and to form all-round defence. As we made our way wearily up the hill, the cold breeze stiffened and I suddenly became aware of my senses again. I was knackered, cold and hungry. With no digging tools, we had to use bayonets to carve our shallow trenches in the frozen mud. Something told me it was going to be a long, hard night. (Curtis, CQB)

The artillery fire mission requested by Lieutenant Weighall, Private Curtis’s Platoon Commander, was so accurate that the first shells exploded on the landing site. Two NCOs sent by Piaggi to guide the Combat Team appeared out of the gloom and explained that the British had surrounded Goose Green; nevertheless the reinforcements reached the settlement.

Except for the clatter of British helicopters and the occasional firing, a dark silence crept across the battlefield. Although Piaggi believed he could withstand a siege but recognized that relief was slim, Army Group, Malvinas encouraged him to abandon Goose Green, make for Lafonia, cross the Bodi Creek bridge and wait for B Company, 6th Infantry Regiment (Major Oscar Jaimet) from the Reserve. Menendez then authorized Pedrozo and Piaggi to decide the best course of action and at 7.30 pm Parada told Piaggi, ‘It’s up to you.’ There is some evidence that the Argentines believed they were facing a brigade and were hopelessly outnumbered. Piaggi later recalled:

The battle had turned into a sniping contest. They could sit well out of range of our soldiers’ fire and, if they wanted to, raze the settlement. I knew that there was no longer any chance of reinforcements from 6th Regiment’s B Company and so I suggested to Wing Commander Wilson Pedrozo that he talk to the British. He agreed reluctantly.

Shortly after midnight, one of Piaggi’s officers used Eric Goss’s CB to contact Alan Miller at Port San Carlos to arrange a ceasefire. Major Keeble sent in two officer prisoners with terms for Piaggi with the ultimatum that if they returned by 8.30 am, surrender had been accepted. He then arranged an all-arms firepower demonstration on call from HQ 3 Commando Brigade, if needed. Thompson placed J Company, 42 Commando (Major Mike Norman) on immediate stand-by to reinforce 2 Para. Company Headquarters and 9 Troop (Lieutenant Trollope) was established from former NP 8901, which had surrendered to the Argentines in April and then been repatriated without giving parole. 42 Commando Defence Troop formed 10 Troop (Lieutenant Tony Hornby). Hornby was the Assistant Training Officer and was in the Chinook crash which killed key intelligence personnel from Northern Ireland. 11 Troop (Lieutenant Colin Beadon) was raised from Milan Troop. When the two Argentines arrived back at Keeble’s headquarters with the news that Pedrozo and Piaggi wanted unconditional surrender, Keeble agreed. It was the Argentine Army’s National Day, usually a time for celebration. Keeble:

1. Contemporary air photograph showing Yorke Beaches and Stanley Airport where the Argentine 2nd Marine Infantry Battalion landed.

2. One of the two 2nd Naval Air Squadron Sea Kings on the Almirante Irizar that landed troops at Stanley.

(Captured photo)

3. 601 Combat Aviation Battalion Puma AE504. This aircraft was shot down by Lt Mill’s detachment at South Georgia.

(Captured photo)

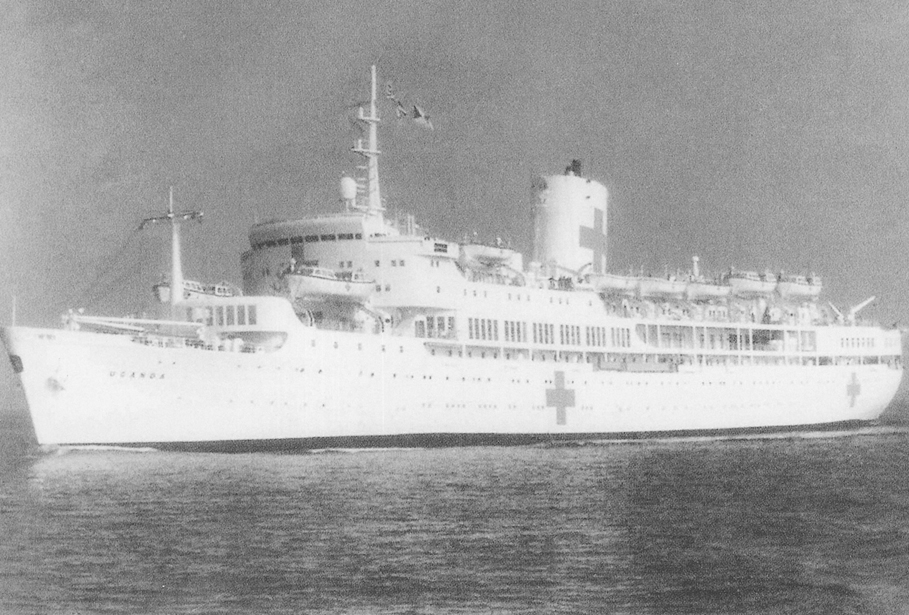

4. Her Majesty’s Hospital Ship Uganda after being requisitioned in early April. Over 500 operations on 730 patients were performed, 20 per cent of whom were Argentine.

(Author’s Collection)

5. Mid-April. A Royal Marine 81mm mortar detachment practices on Ascension Island.

(Author’s Collection)

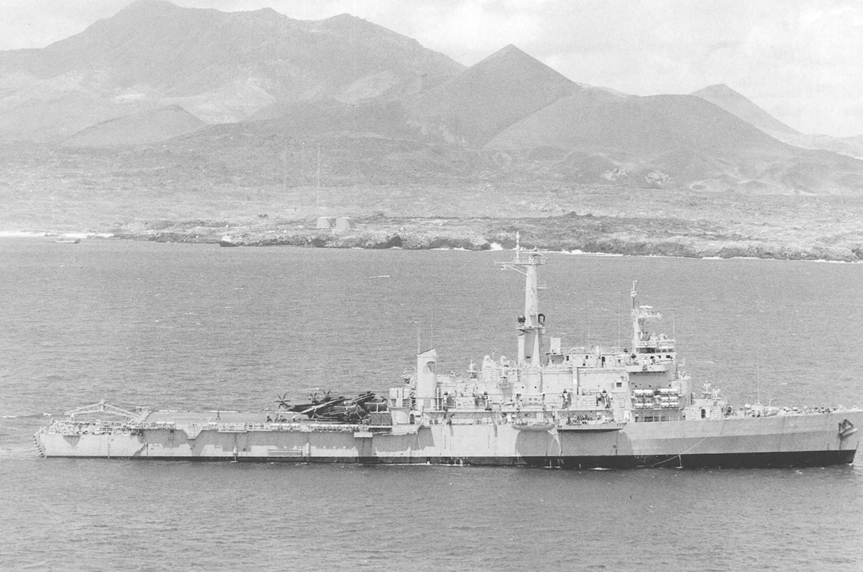

6. HMS Fearless off Ascension Island. Like its sister ship, HMS Intrepid, this LPD was designed to accommodate a battalion landing group of about 750 men. During the campaign, it carried about 900 men and housed a brigade and then divisional HQ.

(Author’s Collection)

7. Two Sea Harriers on board HMS Hermes. The naval Sea Harriers dominated the air war, while the RAF GR3s supported the ground forces.

(Author’s Collection)

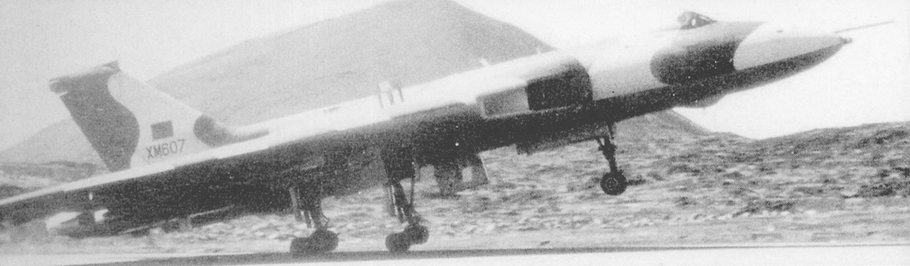

8. 1 May. Piloted by Flt Lt Withers, Vulcan XM607 lands at Wideawake Island after its epic flight ‘Black Buck 1’ to bomb Stanley Airport to open the British offensive.

(Author’s Collection)

9. 5 May. English Bay, Ascension. Troops board an HMS Fearless LCVP. On the right is a LCU.

(Author’s Collection)

10. An 845 Naval Air Squadron Sea King drops an underslung load at Wideawake Airport Ascension Island.

(Author’s Collection)

11. HMS Ardent. Sunk on 21 May.

(Author’s Collection)

12.17 May. HMS Fearless refuelling at sea.

(Author’s Collection)

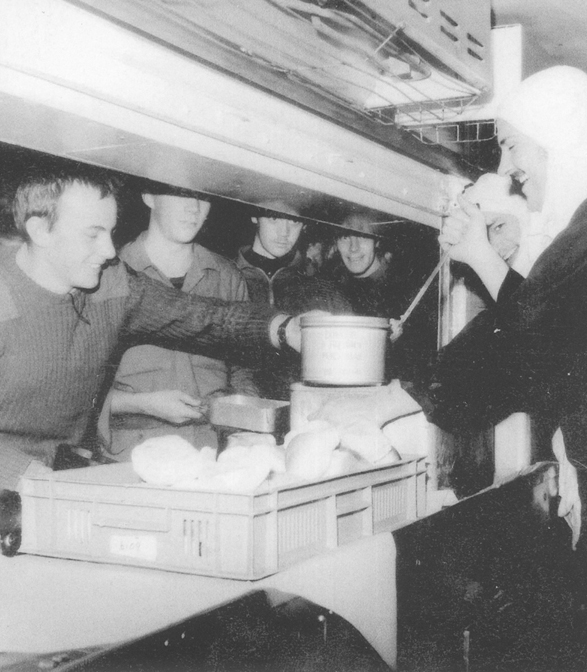

13. 20 May. 40 Commando in the main galley of HMS Fearless after being transferred from Canberra.

(Author’s Collection)

14. 20 May. A Royal Marine of the Fearless Embarked Forces receives his ration of Action Messing – stew and a roll in an explosives canister.

(Author’s Collection)

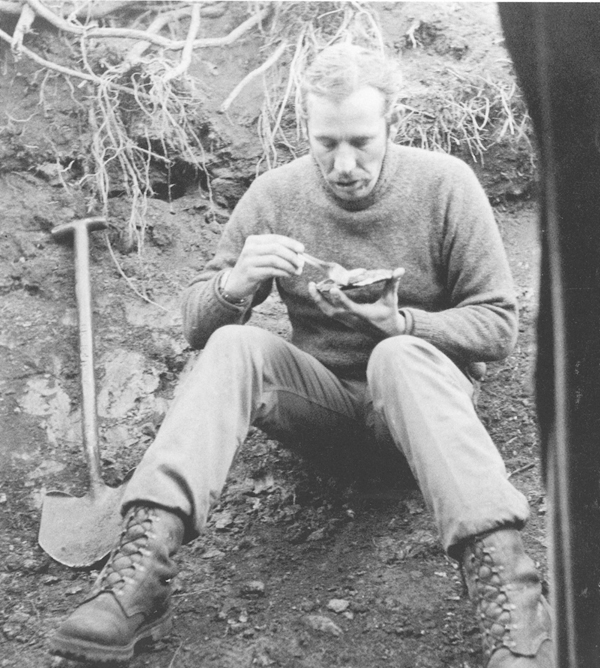

15. 22 May. SSgt Nick van der Bijl (Intelligence Corps) HQ 3 Commando Brigade has a meal in the Intelligence Section bunker at San Carlos.

(Author’s Collection)

16. 24 May. Spiralling smoke from HMS Antelope after being abandoned during the night.

(Author’s Collection)

17. 25 May. The Skyhawk of Lt Ricardo Lucero is shot down in San Carlos Water. Lucero’s parachute can be seen over the bow of RFA Sir Galahad. He was picked up, badly wounded, by Marine Geoff Nordass.

(1st Raiding Squadron RM)

18. 29 May at San Carlos. Goose Green garrison commander, Vice Comodoro Perdroza, is welcomed by Brigadier Thompson. Taking the briefcase in Major Richard Dixon. Behind him is Corporal Dean (Royal Military Police), who was Thompson’s close escort. In the background is a Type 12 destroyer.

(Author’s Collection)

19. Royal Marine LCpl ‘Smudge’ Smith at the entrance of the San Carlos interrogation centre – Hotel Galtieri – a complex of several stables. The gap in the corrugated iron leads to air-raid trenches.

(Author’s Collection)

20. 4 June. A 45 Commando mortar detachment leaves Teal Inlet.

(Author’s Collection)

21. 7 June. LCU F4 at Bluff Clove. Next morning it was sunk in Choiseul Sound.

(1st Raiding Squadron RM)

22. 8 June. Troops abandoning Sir Galahad. The 847 Naval Air Squadron AS Wessex piloted by Lt Hughes uses its rotor down-wash to shepherd a life raft from the ship.

(1st Raiding Squadron)

23. 9 June. HQ 3 Commando Brigade prepares to leave Teal Inlet in its BV202 Snocats.

(Author’s Collection)

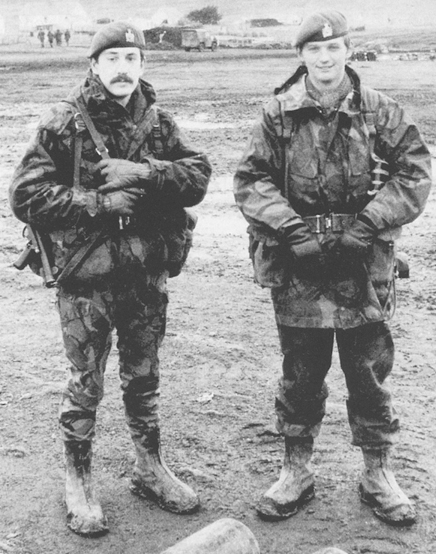

24. About 9 June. Two members of 81 Intelligence Section, Sergeant Steve Massey and Corporal Barry Lovell. Both wear rubber boots to prevent trench foot and other infections caused by wet and cold feet.

(Author’s Collection)

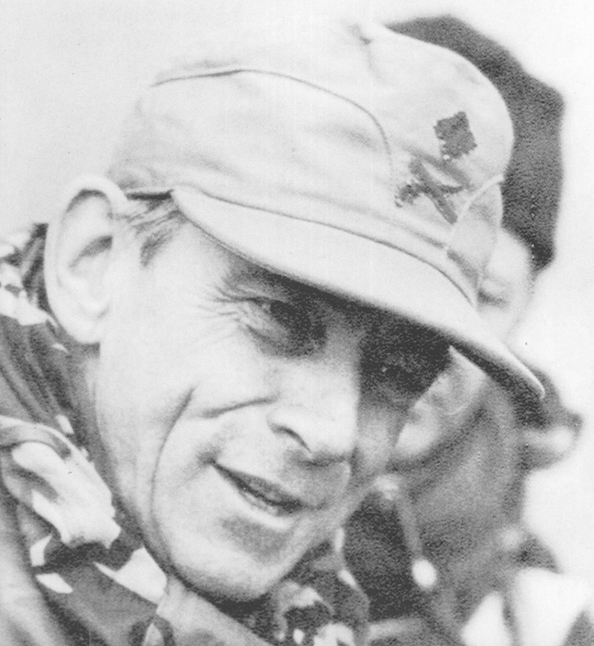

25. Major General Moore wearing his distinctive desert cap.

(Author’s Collection)

26. 12 June. A Royal Marine sergeant helps an Argentine medic with a wounded Argentine soldier after the battle for Mt Harriet. He wears nuclear, biological and chemical overboots in order to protect his feet.

(Author’s Collection)

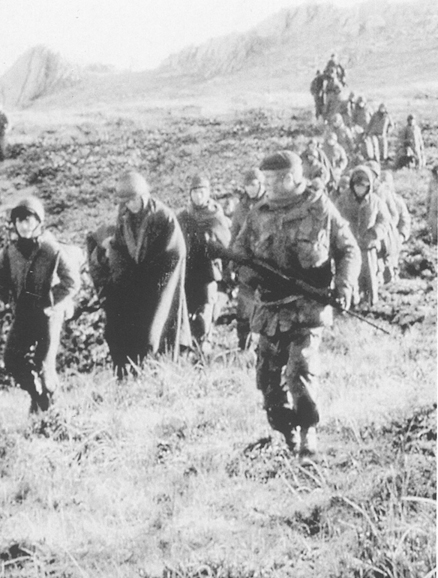

27. 12 June. 45 Commando escorts prisoners from Two Sisters to the rear.

(Author’s Collection)

28. 16 June. A waterlogged Argentine M56 pack howitzer gun position on Stanley Common.

(Author’s Collection)

29.17 June. The Argentine icebreaker Almirante Irizar at Stanely collecting Argentine wounded.

(Author’s Collection)

30. A convoy of ships near the Falklands after the surrender.

(Author’s Collection)

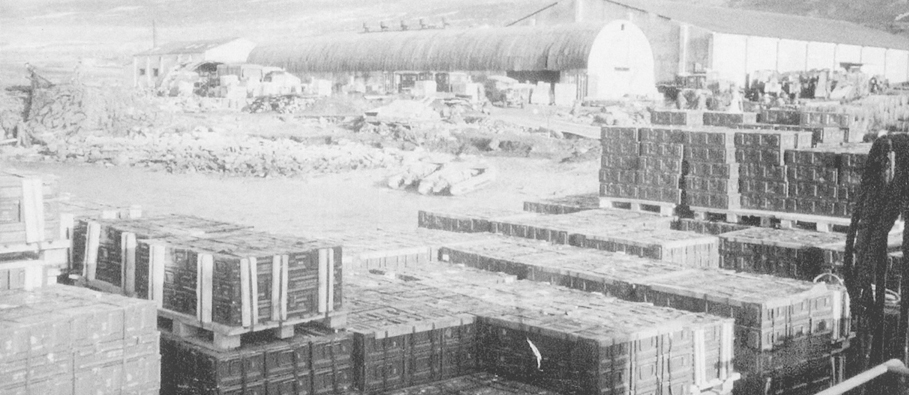

31. The logistic dump at Ajax Bay (Red Beach).

(1st Raiding Squadron)

32. Argentine Skyhawk. Part of a collection of photos donated to the Task Force.

(Author’s Collection)

33. 245 armoured car several years after the war.

(Author’s Collection)

34. Argentine prisoners collect food from an Argentine field kitchen at Stanley Airfield.

(Author’s Collection)

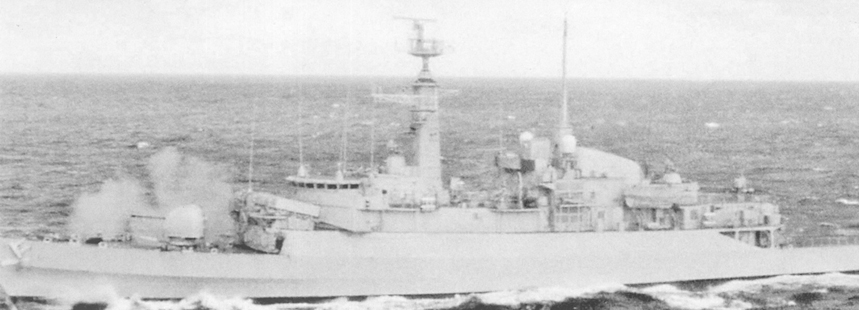

35. The Type 42 destroyer HMS Exeter (Capt Hugo Balfour LVO). On 7 June, a clear day, she shot down with a Sea Dart a 1st Air Photo Group Learjet flying at 40,000ft over San Carlos.

(Author’s Collection)

36. HMS Hermes (Capt Lindley Middleton DSO). With HMS Invinsible, she was a vital factor in competing for air superiority. For the San Carlos landings, she carried 15 naval Sea Harriers, 6 RAF GR3s, 6 Sea Kings, 2 Lynx and 1 Wessex.

(Author’s Collection)

Eventually about 150 people in three ranks marched up and formed a hollow square. An officer in an Argentine Air Force uniform walked up to me and saluted. I asked for his pistol and took it. When we looked closely we saw that these people weren’t soldiers at all. They were airmen. We reckoned there must have been 150 of them. I said ‘Where are the soldiers?’ He indicated the settlement and said ‘They’re coming.’ Three or four of us moved forward to look down into the settlement. There, to our amazement, must have been 1,000 men, marching up in three ranks. We just held our breath. Somebody murmured ‘I hope they don’t change their mind.’

For the Argentine 12th Infantry Regiment, 29 May would always be remembered as the day it capitulated. Piaggi burnt his regimental flag. It was also the day when snow first fell across the bleak islands. Broadcasting to the Argentine people and referring to the catastrophe, President Galtieri had this to say:

At this time of supreme sacrifice before the altar of the country, with all the humility that a man of the armed forces may have deep in his heart, I kneel before God, because only before Him do the knees of an Argentine soldier bend. The Country’s arms will continue fighting the enemy for every Argentine portion of land, sea and sky, with growing courage and efficiency, because the soldier’s bravery is nourished by the blood and sacrifice of his fallen brothers.

The battle cost 2 Para sixteen killed, half of them from D Company, and thirty-three wounded. A Royal Marine helicopter pilot and a commando sapper were also killed. Of about 300 who took part in the fighting, Task Force Mercedes lost 45 killed and 90 wounded, with 12th Infantry Regiment losing 31 killed, 25th Infantry 12 killed, 5 from 8th Infantry, 2 from 1st AA Group, 4 Air Force and 1 Navy pilot; 1,007 were taken prisoner. That evening Air Commodore Pedrozo and Lieutenant Colonel Piaggi were helicoptered to San Carlos and were met by Brigadier Thompson. Piaggi, bitter and angry, said that Task Force Mercedes ‘would have fought until the last man if Parada had demanded it’. Nevertheless, his men had forced 2 Para to fight a long and confusing battle, longer than any other Argentine commander would do. He had confounded Jones’s theory, ‘Hit them really hard and they will fold.’

3 Commando Brigade was suddenly faced with dealing with the largest number of prisoners captured since the Second World War, an event made worse by the loss of the prisoner-of-war camp on the Atlantic Conveyor and the need to support the breakout. Eventually the prisoners were flown to San Carlos where about 200 were interrogated at Hotel ‘Galtieri’ before being transferred to the prison camp at Ajax Bay. Most were quickly ferried to Norland for repatriation.

Great Britain had demonstrated resolve and the US encouraged Argentina to consider a solution to the war. For Brigadier Thompson, now that the tricky and pointless battle of Goose Green was over, he could concentrate on attacking Stanley.