This was a fun little exercise to turn those arbitrary KENP read numbers into something more meaningful. It’s also necessary for the next step; but fear not, this is all done by the simple spreadsheet I’ve provided.

Again, once you have the KENPC number for each book, divide your number of page reads for the month by the KENPC value for that book, and you’ll have the number of “full reads” of that book.

Given a KENPC value of 514 for book 1, and a total pages-read of 45833, we would end up with:

45833 ÷ 514

= 89

This means that 89.16 complete read-throughs of book 1 were made.

“Wait! You have no way of knowing that those page reads accounted for 89 full reads. It could have been 178 half-reads!”

If you had the reaction above, you’re completely right in your thinking. We don’t know this to be true—especially on book 1. However, we don’t calculate CRT (cumulative read through) for book 1, so it doesn’t really matter that much.

We do know, however, that anyone who reads book 2 likely read all of book 1 – so when we calculate our CRT for book 2 and beyond, we’ll still get a meaningful number.

Remember, for KU, we don’t get paid by the full read, but rather by each page read. Thus, for our net profit calculations, whether or not someone read the full book doesn’t really matter; all that matters is the page-reads volume.

Converting KENP reads to full book numbers is handy because it can tell you the value of KU to you, vis-à-vis how many books in the program your readers are consuming.

Again, fear not, all of this is in the spreadsheet linked at the end of this section.

You can safely assume that all your sales come from your ads, in one form or another—unless you’re doing a lot of other promo as well. To know if your ads are working, you need to track sales from those ads. If you’re selling no books, this is pretty easy to determine.

However, if you are already selling books, and trying out a few different ads, it can be a bit more difficult to know which ones are working.

So how do you tell how many sales come from an ad?

Officially, there is no way to do this. Unofficially, it is possible to get a rough idea via Amazon Affiliate tracking codes. Is this against the terms of service for the Amazon Affiliate program? Yes it is. You are not allowed to use affiliate codes on any service where you bid for keywords (aka Facebook Ads, Twitter Ads, Google Ads, etc…), so do it only at your own risk, and do it only to prove out an ad, and then stop.

If Amazon catches you at this, they will shut down your affiliate account; however, the links you made with it will still work, so it is not the end of the world.

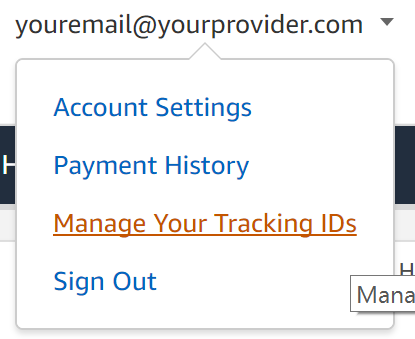

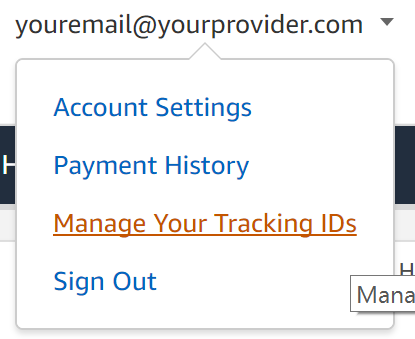

Ideally, you should have different codes for each ad so you can separate your revenue. You can do this by clicking on your email at the top of the page in the affiliate website, and then clicking on “Manage Your Tracking IDs”.

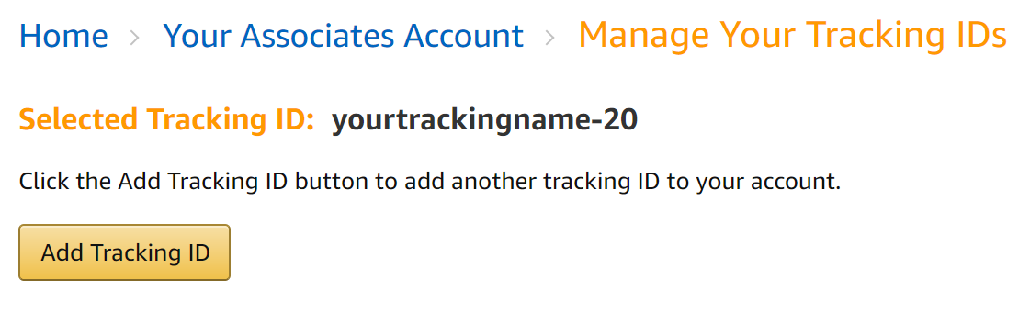

Then, on the following page, you can add new tracking IDs by clicking the “Add Tracking ID” button.

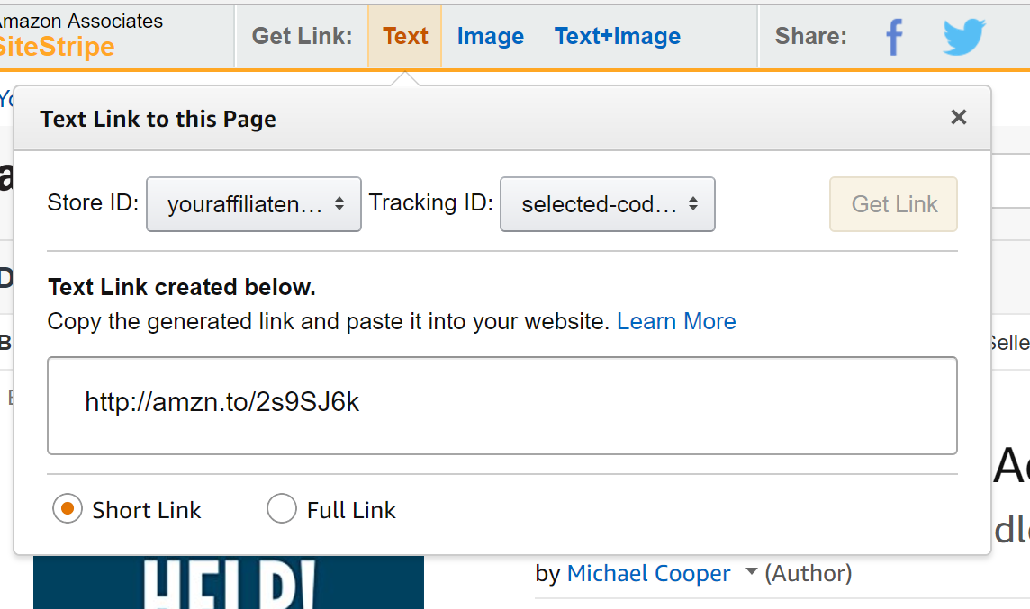

Now whenever you make an ad, you can use the affiliate bar on Amazon to get the appropriate link for your book and ad.

It’s important to note that like with AMS ads, there is absolutely no reporting on KU borrows and reads. You will have to assume that the percentage of KU reads you get on average applies to your advertising ROI as well (more on that later).

An aside for any Amazon employee who happens to read this:

We are not using affiliate codes to game the system or make extra money on the side. We are using them because it is the only way we can track the conversions on our ads. We would gladly use a system that didn’t pay us affiliate money, but gave us real, useful data on the conversion and effectiveness of our product pages rather than use affiliate codes.

We are begging you for such a service.

If you’re in KU, you can assume that some number of the people who land on your product page (through your ads, but also through any other means) are KU readers, and invisibly borrow your book.

But how do you track these fine folks?

If some of your ad respondents are reading in KU, then they are a part of your ROI. Well, then. What you need to do is work out the ratio of sales to your full KU book reads.

IMPORTANT: Do not work out this ratio by purely comparing sales earnings to KU earnings.

The reason you should not look at your ratio of KU-reads-to-sales from a dollars perspective is because books like your 99c first in a series will make significantly more in KU. Conversely, your later books at $4.99 will make more from sales (depending on your book’s length).

This means that looking at the relationship of KU reads to dollars is not a comparison of actual books read—which is what we need in order to estimate a ratio of humans reading books, as opposed to pages being read.

Since you did the math in the previous section (or filled out the handy-dandy spreadsheet), you can compare your full reads of each book to your sales of each book, and work out the ratio of sales to KU reads, as well as determine how many readers are passing through your series in aggregate.

This is important because you advertise to people, not net profit numbers.

If you have 84 sales and 89 full reads, you add the two numbers together, then divide that number by the KU number to get the percentage of all your full reads.

84 + 89 = 173

89 ÷ 173 x 100

= 51.4%

But what we really need is the ratio. To get this, you divide your full KU reads by your sales.

89 ÷ 84

= 1.06

This means that for every sale you make, you get 1.06 full KU reads of that book as well.

Because we have little data on KU borrows—where they come from, or how many we have—we can simply assume that a certain percentage of the people who you advertise to, who search for your books or keywords, etc… are just magically “KU readers”. We also have to assume that the ratio of “buyers” to “KU readers” is the same, regardless of the route they took to get to your product page.

In the example above, we assume that for every person who lands on your book’s product page and hits “Buy,” 1.06 people land there and click “Read for Free”.

Because this is an average, we can (mostly) safely apply it to our ads, as well. For every sale you see logged in Amazon’s affiliate site for a given ad (in this scenario), we’d assume that another 1.06 people also borrowed.

Let’s continue with our example of a 5-book series. We’re advertising book 1, and we know that for each sale of book 1, we make $5.94. Also, in theory, a KU reader borrowing book 1 will make us $10.27.

However, I really don’t feel comfortable assuming that so many KU readers land on and borrow from my product page. I’m going to pretend that 50% of all KU readers get to my book by magic (as in, Amazon specially promotes KU books to them through an avenue by which it does not promote non-KU books). Therefore, I’m going to cut that $10.27 number in half.

“Wait…what? Why did you just cut your reads revenue in half?”

The base assumption I made is that all readers are equal. If my ratio of buying readers to borrowing readers is 1.06, then I’m assuming it’s 1.06 everywhere.

That assumption means that if I am walking down the street and I throw a rock, I’ll hit one buying reader, and 1.06 borrowing readers.

But what if Amazon specially promotes KU books to those borrowing readers through some other avenue, and a large percentage of my KU borrows and reads have nothing do with my effort?

I honestly don’t know; but to stay safe, that is why I cut my net profit from magical KU readers in half.

OK, back to working out our net profit...

I still multiply the 50% cut of my estimated borrows revenue by the reads KU ratio we worked out in the prior chapter, which means I multiply it by 1.06.

10.27 ÷ 2 x 1.06

= $5.44

And now, for our grand total, a confirmed sale of book 1 in our 5-book series, via an ad, will net us:

5.94 + 5.44

= $11.38

Cost of Sale is a common sales and marketing term, and it’s pretty straightforward. What does a sale cost you? Hopefully it’s less than your net profits on the ad, or you’re losing money.

What you will probably find is that about 30 clicks on a Facebook ad result in one sale (give or take 15 clicks). This can vary wildly, and the only way to know for sure is to use affiliate tracking. Again, using affiliate links on Facebook ads is against Amazon’s TOS for their affiliate program, so you should only use it for a short time to confirm the ad is converting; even then, know that Amazon may shut down your affiliate account for doing so.

However, this is the only business I’ve ever been in where you can spend tens of thousands of dollars in advertising for a distributor, but have no insight into the sales funnel. Which is utter garbage.

Anyway, let's assume you see a sale for every 30 clicks on a Facebook ad. This means that the highest cost per click you can tolerate is the result of some simple math. Take your net profit we worked out in the prior section and divide it by 30 (our starting estimate for how many clicks it takes to make a sale).

11.38 ÷ 30

= $0.38

There you have it. Given our calculated net profit from a sale, and a starting estimation of a sale every 30 clicks, the maximum cost per click we can tolerate is $0.38.

If our average CPC is over that, we’re losing money on the ad.

I want to take just a moment to talk about this. I think a lot of people believe that if someone clicks on a link in your ad, or in your newsletter, said click will turn into a sale.

It probably won’t.

The conversion rate on your Amazon book page is probably only 2-5%, tops (on average, when you’re not running a promo or a new release). When I talk about a sale for every 30 clicks, that is a nice, middle of the road, 3% conversion rate.

Even if you have a great, amazing, rockin’ 10% conversion rate, that’s only a sale once every 10 clicks.

That conversion rate will also be affected by the price of your book. Free or $0.99 books convert very well. Higher priced books convert at lower percentages.

On the flipside, a lot of people who pick up free books don’t read them, and even a lot of $0.99 books don’t get read. You will see this reflected in your read-through.

Also, if (in our hypothetical 5-book series) the first book was at $4.99, and our read-through was the same (it would probably be better; the higher-priced your first book is, the more read-through you get), then we make almost $3 more per sale of book 1 in the read-through calculator.

However, your ads will be less effective, and you’ll sell fewer books. Like everything in life, it’s a trade-off.

The debate on pricing will probably go on forever, and there are as many opinions as there are authors. However, when it comes down to it, there are some key principles at play:

What do I do, you ask?

I price my first at $0.99, because I want readers more than money. Readers are great, because if they like you, they give you money!

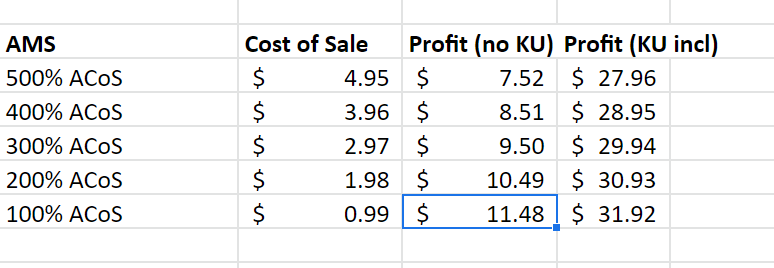

While this book isn’t about AMS ads, the math we do to determine the read-through royalties from follow-on books works for AMS as well.

Once the sheet is filled out, it knows the royalty rate of each book and can work out what profit you make at various ACoS levels.

This makes identifying profitable AMS ads very simple.

OK, that was probably more math than you wanted to do, and math may not be your thing.

To make this simpler and a bit more foolproof, I’ve created a spreadsheet where you can plug in all your sales numbers for a month, and it will give you your net profits per sale and per read.

You then can add your expected profits together, and divide by how many clicks it takes to make a sale to arrive at your Cost per Click tolerance level.

This spreadsheet will allow you to calculate read-through in a series. There is one tab for a 5-book series, and another tab for a 10-book series. If your series doesn’t have those exact numbers, simply input 0 for sales and reads for any books you don’t have.

Also, if you have a permafree first book, put in 0 for the royalty rate.

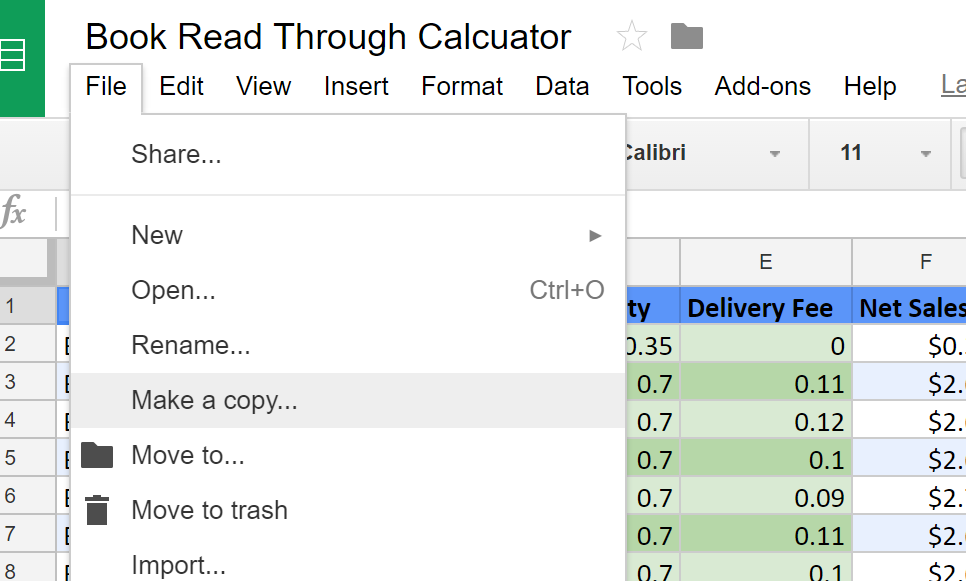

Spreadsheet on Google Docs

(You will need to save or copy it to edit)

Alternatively, the Readerlinks.com service now has a feature based on this work that will also calculate your read-through values.